Abstract

Escherichia coli is a versatile pathogen causing millions of infections in humans every year. This bacterium can form multicellular aggregates when it expresses a self-associating protein, antigen 43 (Ag43), on its surface. We have discovered that Ag43-expressing E. coli cells are efficiently taken up by human defense cells, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), in an opsonin-independent manner. Surprisingly, the phagocytosed bacteria were not immediately killed but resided as tight aggregates within the PMNs. Our observations indicate that Ag43-mediated uptake and survival in PMNs constitute a mechanism to subvert one of the primary defense mechanisms of the human body.

Escherichia coli is a member of the normal intestinal flora of humans. However, it is also one of the most prominent human pathogens and accounts for millions of infections every year. This versatile pathogen can infect a variety of tissues and causes a broad spectrum of diseases, such as urinary tract infections, diarrhea, pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis (4, 15, 24). Microorganisms that embark on infecting human hosts face formidable obstacles. Thus, human tissues are superbly equipped to deal with hostile intruders. Apart from a range of specific and nonspecific antimicrobial mechanisms, the invader must face phagocytic killer cells in the form of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). PMNs usually form the first line of defense against invading microorganisms and are a critical component of the human innate host response against bacterial infections (13). PMNs readily accumulate at sites of acute inflammation, and during bacterial infections, such as those of E. coli, the PMNs are the first phagocytes to arrive. Invading bacteria may be opsonized by complement proteins or antibodies and subsequently phagocytized and killed by PMNs.

Antigen 43 (Ag43) is a surface protein of E. coli that confers bacterial cell-cell aggregation via an intercellular Ag43-to-Ag43 handshake mechanism (8, 12, 17). Ag43-mediated aggregation can be visualized macroscopically as flocculation of cells from static liquid suspensions; hence, the name flu was originally coined for the corresponding genetic locus by Diderichsen (6). Ag43 is a member of the autotransporter protein family, which is defined by the fact that the proteins contain all information required for traverse of the bacterial membrane system and final routing to the bacterial cell surface (9). Ag43 is found in most E. coli strains, including many pathogenic strains (12, 17, 19). Ag43 is a multifunctional protein and promotes bacterial binding to some human cells as well as biofilm formation on various surfaces (12, 22).

We have previously demonstrated that Ag43-mediated aggregation enhances bacterial tolerance to bactericidal agents (21). Human blood contains multiple antibacterial agents, including PMNs. With a view to see if Ag43-mediated bacterial aggregation provided enhanced resistance toward antibacterial agents, we probed the ability of Ag43-expressing E. coli K-12 to survive exposure to human PMNs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

All strains and plasmids are described in Table 1. All E. coli strains used in this investigation were Δflu derivatives of the E. coli reference strain MG1655, except for experiments where the urinary tract infectious E. coli strain 83972 was used. MG1655 and 83972 strains used for fluorescence microscopy investigations were fluorescently tagged with gfp and yfp, respectively, OS56 (MG1655 Δflu attB::bla-PA1/04/03-gfp*-T0), and VR48 (83972 attB::bla-rrnBP1-yfp-T0) as described previously (7), and MS528 (MG1655 Δflu Δfim) was used in experiments not requiring fluorescence tagging. Transformants were selected on ampicillin-containing plates and checked for their ability to fluoresce. Proper insertion of the fragment into the λ attachment site was confirmed by PCR. Bacteria were grown at 37°C on solid or in liquid LB supplemented with appropriate antibiotics.

TABLE 1.

Escherichia coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MG1655 | K-12 reference strain | 3 |

| MS528 | MG1655 Δflu Δfim | 11 |

| OS56 | MG1655 Δflu attB::bla- PA1/04/03-gfpmut3b*-T0 GFP | 23 |

| 83972 | Asymptomatic bacteriuria E. coli isolate | 2 |

| VR48 | 83972 attB::bla-rrnBP1-yfp-T0 YFP | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLH44 | aah-aidA genes from E. coli O126:H27 strain 2787 in pACYC184 | 23 |

| pPKL330 | flu gene from E. coli in pACYC184 | This study |

| pSF2 | flu gene from pPKL330 with RGD motif at position 208 changed to KGE | This study |

Cloning and DNA manipulation.

All plasmid constructs were derivatives of the pACYC184 cloning vector with the tetracycline resistance gene promoter for consecutive expression. The flu gene encoding Ag43 was amplified by PCR and cloned into the BamHI and SalI sites of pACYC184, resulting in plasmid pPKL330. pPKL330 was transformed into MS528 (MG1655 Δflu Δfim), OS56, and VR48. All strains carrying the Ag43-expressing plasmid showed heavy aggregation, and the whole batch was used in the experiments. The RGD motif at position 208 in Ag43 was mutated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), such that RGD was changed to KGE using primers 655 (5′-CCGGGCAGTTTGTTAAAGGGGAAGCCGTACGCACAACCATC-3′) and 656 (5′-GATGGTTGTGCGTACGGCTTCCCCTTTAACAAACTGCCCGG-3′). The resulting plasmid, pSF2, with mutant flu was introduced into E. coli strains MS528 and OS56.

Isolation of human PMNs.

Human blood samples were obtained from healthy volunteers by venous puncture and collected in BD Vacutainers with 0.129 M sodium citrate (388335; Becton Dickinson). The blood was mixed with dextran (T-500) 1:5, and the erythrocytes were left to precipitate for 40 min. The supernatant was applied to Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield PoC) and centrifuged at 850 × g for 15 min at 5°C. The pellet was treated with 2 ml 0.2% NaCl to lyse remaining erythrocytes. Lysis was terminated by addition of 2 ml 1.6% NaCl and 6 ml RPMI 1640. The cells were centrifuged at 350 × g for 10 min at 5°C, the supernatant was discarded, and the PMNs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 buffer at 5 × 106 PMNs/ml.

Blood sensitivity.

Bacteria were tested for sensitivity to human whole blood by incubating the individual E. coli strains with blood to a final blood concentration of 75%. Overnight cultures of bacteria grown in LB were standardized and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (to a density of 4 × 109 CFU/ml). Aliquots of cells (triplicates) were kept in microtiter plates at room temperature for 2 h to allow aggregation, followed by addition of fresh human blood or RMPI 1640 buffer (control). The mixtures were shaken at 200 rpm and 37°C for 15 min, and serial dilutions were plated.

Bacterial internalization by PMNs.

Internalization of bacteria was examined by confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM). Overnight cultures of fluorescent bacteria (green fluorescent protein [GFP] or yellow fluorescent protein [YFP]) were standardized and suspended in PBS to a density of 4 × 109 CFU/ml. Aliquots of cells (50 μl) were kept in microtiter plates at room temperature for 2 h to allow aggregation, followed by the addition of 150 μl freshly purified PMNs or RPMI 1640 buffer for control. Bacterium-PMN interaction was visualized after incubation for 45 min at 37°C and 200 rpm. All CSLM images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 510 system (Carl Zeiss) equipped with an argon laser and a helium-neon laser for excitation of the fluorophores. Simulated fluorescence projections were generated using the IMARIS software package (Bitplane AG). Images were further processed for display using the PhotoShop software (Adobe).

Internalization of E. coli in PMNs was assessed by 45-min incubation of bacteria and PMNs prepared as above, followed by the addition of gentamicin (18 μg/ml) and another 30 min of incubation. Bacterial survival in PMNs was tested by preparing mixtures of PMNs and bacteria as described above, followed by incubation for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min at 37°C and 200 rpm. Bacterial viability was determined by plating serial dilutions. To block bacterial uptake by phagocytosis, the isolated PMNs were treated with 3 μM cytochalasin D (C8273; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C before incubation together with bacteria followed by gentamicin treatment as described above.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of phagocytosis.

Phagocytosis of bacteria by PMNs was analyzed using FACSort (Becton Dickinson) equipped with a 15-mW argon ion laser turned to 488 nm for excitation. Light scatter and exponentially amplified fluorescence parameters from at least 10,000 events were recorded in list mode after gating on light scatter to avoid debris, cell aggregates, and bacteria on its own. The instrument was calibrated using Calibrite (Becton Dickinson). PMNs were identified according to their morphology and their content of DNA. GFP-expressing E. coli cells, both nonexpressing control cells and Ag43-expressing cells, were mixed with PMNs as above. External E. coli cells were removed by washing in cold PBS. The remaining PMNs were fixed in fluorescence-activated cell sorter lysing solution (Becton Dickinson) containing 150 μg/ml propidium iodide (P-4170; Sigma) for discrimination of eukaryotic cells according to their DNA content.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ag43-expressing E. coli survives exposure to PMNs.

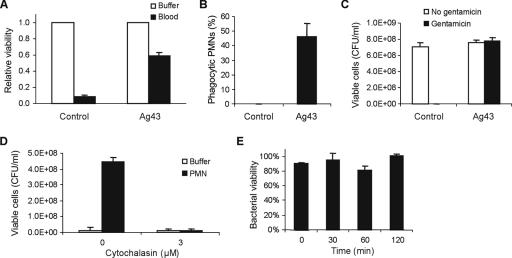

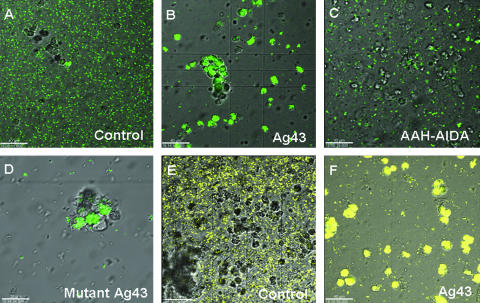

As a consequence of our previous observations concerning the Ag43-mediated aggregation-enhanced bacterial tolerance to bactericidal agents (21), we wanted to investigate if Ag43-mediated aggregation also protected the bacteria against human blood. Human blood contains multiple antibacterial agents; for example, the complement system and PMNs. It turned out that Ag43-expressing E. coli survived sixfold better than nonexpressing control cells when exposed to human blood (Fig. 1A). We suspected that bacterial aggregates were difficult to ingest for the PMNs. To investigate this phenomenon further, a combination of E. coli-expressing GFP, washed PMNs, and CSLM was employed. This technique permits spatial imaging of PMNs and bacteria. When bacteria and PMNs were mixed and examined by fluorescence microscopy, we discovered that Ag43-mediated bacterial aggregation did not protect bacteria against uptake by PMNs, but it actually enhanced uptake, i.e., the large majority of Ag43-expressing E. coli was taken up by PMNs in an opsonin-independent manner, whereas nonexpressing controls were not (Fig. 2; see movie in the supplemental material). This result was further corroborated by flow cytometry, which demonstrated that up to 50% of PMNs were phagocytic, i.e., they contained internalized Ag43-expressing bacteria tagged with GFP (Fig. 1B). To discriminate between bacteria that were internalized and those that were firmly bound to the PMN surface, we added gentamicin to a mixture of bacteria and PMNs (Fig. 1C). For the control, the number of viable bacteria decreased significantly in the presence of gentamicin. In contrast, the number of Ag43-expressing bacteria was not reduced by the treatment. Since gentamicin is unable to penetrate the PMN plasma membrane and kill intracellular bacteria (27), this experiment demonstrated that Ag43-expressing bacteria were protected by PMN internalization. To bolster the notion that enhanced resistance to gentamicin of Ag43-expressing E. coli was due to PMN phagocytosis, the PMNs were treated with cytochalasin D that blocks phagocytic bacterial ingestion by disruption of the actin microfilaments (16, 26). Gentamicin efficiently killed Ag43-expressing E. coli bacteria that were incubated with cytochalasin D-treated PMNs, while untreated PMNs protected the bacteria from being killed (Fig. 1D). Taken together, the results indicate that Ag43-expressing E. coli bacteria are specifically internalized by PMNs via phagocytosis.

FIG. 1.

E. coli exposed to human blood and internalization of Ag43-expressing E. coli by PMNs. (A) E. coli strain MG1655 Δflu, harboring control plasmid (pACYC184) or Ag43-encoding plasmid (pPKL330), was incubated with blood or buffer for 15 min, and bacterial viability was determined. Results are presented as survival in blood compared with buffer and means from three independent experiments; error bars indicate standard deviations (values were 4.4 × 108 and 6.0 × 108 CFU/ml in buffer for control plasmid and Ag43, respectively). (B) Bacterial uptake by human PMNs monitored by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of phagocytic PMNs after bacterial incubation for 45 min at 37°C. Phagocytic green fluorescent PMNs were detected after incubation with GFP-expressing E. coli control (pACYC184) and Ag43-expressing (pPKL330) cells followed by a wash of external cells. Values are means of results from 10 samples, and error bars indicate standard deviations (unpaired t test, P < 0.0001). The experiment was performed in duplicate with separate cultures and blood donors. (C) Internalization of bacteria in PMNs was assessed by addition of gentamicin (18 μg/ml) to mixtures of PMNs with control or Ag43 E. coli; bacterial viability was determined after 30 min of incubation. Error bars indicate standard deviations of results from three independent experiments. (D) Internalization of Ag43-expressing bacteria in PMNs was blocked by treatment of PMNs with cytochalasin D, leading to lack of protection against gentamicin. Error bars indicate standard deviations of results from two separate experiments. (E) Survival of phagocytosed Ag43-expressing E. coli inside PMNs. Coincubation of bacteria and PMNs for 0 to 120 min at 37°C was followed by serial dilutions and plating. Bacterial viabilities are presented relative to survival in buffer and are means of results from three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 2.

Bacterial adherence to human PMNs. Fluorescent E. coli cells, nonexpressing control (pACYC184), Ag43-expressing (pPKL330), and AIDA-expressing (pLH44) cells, were mixed with PMNs. (A to C) Representative fluorescence micrographs of E. coli MG1655 Δflu (GFP), demonstrating that the majority of Ag43-expressing cells were taken up by PMNs in an opsonin-independent manner while neither control cells nor AIDA-expressing cells were taken up by PMNs. (D) E. coli MG1655 Δflu expressing the mutant Ag43 (pSF2; with RGD motif changed to KGE) was also taken up by PMNs. (E and F) Fluorescence micrographs of E. coli 83972 (YFP), nonexpressing control and Ag43-expressing cells, illustrating Ag43 adherence and uptake to PMNs. All images were obtained after coincubation of E. coli cells and PMNs for 60 min at 37°C. Bars, 40 μm (A, B, C, E, and F), 20 μm (D).

To test if the bacterial host background played a role, we also investigated PMN uptake of a wild-type E. coli strain, i.e., the urinary tract infectious E. coli strain 83972. Fluorescence-tagged E. coli 83972 cells expressing Ag43 were presented to PMNs and subsequently inspected by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). Ag43-expressing E. coli 83972 cells were efficiently taken up by the PMNs, whereas E. coli 83972 controls were not, suggesting that the uptake was not restricted to a particular host.

Ag43-assisted bacterial uptake by PMNs does not require the RGD motif.

Proteins containing an RGD motif have been implicated in binding and internalization of microorganisms by human integrin receptors (10). Ag43 contains an RGD motif at position 208, and it seemed conceivable that this motif played a role in PMN uptake of Ag43-expressing bacteria. To test this, we made a version of Ag43 with an RGD-to-KGE change by PCR-assisted site-directed mutagenesis of the corresponding gene. However, bacteria expressing the KGE version of Ag43 were taken up by PMNs with similar efficiency as bacteria that expressed the wild-type version of Ag43 (Fig. 2D). The RGD-to-KGE change does not affect the aggregation properties of Ag43.

The bacterial uptake is Ag43 specific rather than dependent on aggregation.

The lack of RGD motif-dependent uptake led us to speculate that aggregation per se could provoke PMN uptake. To investigate this, we used another autotransporter protein, AIDA, which shares ∼25% sequence identity with Ag43 and also causes bacterial aggregation (23). Meanwhile, aggregating bacteria expressing AIDA were not taken up by PMNs any better than the controls (Fig. 2). Taken together, the results indicate that Ag43-assisted bacterial uptake by PMNs does not require RGD motifs nor does bacterial aggregation by itself suffice to provide uptake.

Ag43-expressing internalized cells survive inside PMNs.

PMN phagocytosed bacteria are usually killed rapidly (14, 18), and we therefore set out to investigate the fate of phagocytosed Ag43-expressing bacteria. Accordingly, the survival rate of such bacteria was monitored for 120 min (Fig. 1E). It transpired that, during this period of time, no reduction in bacterial viability was observed, indicating that the tight aggregates of Ag43-expressing bacteria tolerated antimicrobial mechanisms inside the PMNs for extended periods of time. In contrast, bacteria devoid of Ag43 were not internalized at all and did not survive as well in whole blood compared to Ag43-expressing bacteria (Fig. 1A and 2). Ag43-mediated cell aggregation significantly protects bacteria against exposure to hydrogen peroxide (21). Since PMNs use peroxides to eliminate bacteria, similar protective mechanisms could be at play inside the PMNs. It therefore seems that Ag43 not only confers efficient bacterial uptake in PMNs but also seems to provide a survival mechanism for the bacteria after phagocytosis.

In this study, we have described a possible bacterial evasion technique, “hiding-in-the worst-place,” i.e., inside the killer cells of the host defense. The bacterial strategy for the uptake and survival of Ag43-expressing E. coli might be evasion, survival, and possibly transport. Since the PMNs play a central role in the host defense, it should follow that the ability to foil PMN-mediated killing should be a major advantage for an infecting microorganism. E. coli is the primary cause of urinary tract infections in humans (24). The antibacterial defense of the urinary tract is highly dependent on innate immunity where PMNs are crucial players (25). Arguably, Ag43-mediated uptake and survival in PMNs could play an important role in this type of infections. The sessile state of bacteria (biofilms, microcolonies, and aggregates) shows an increased tolerance to a variety of antimicrobial measures compared to its planktonic counterparts (5, 20). Ag43 has been shown to be expressed by E. coli in the urinary tract in the mouse model (1). By expressing Ag43, the bacteria become readily internalized, and we speculate that they resist elimination internally due to aggregation. Firmly inside the PMN, the bacteria are protected from the remaining host defenses, as evidenced by the improved survival observed in whole blood. However, it needs to be clarified whether it is the internalization or the clumping which protects the cells. Even killing by antibiotics in general may be evaded within the PMNs. It is interesting to speculate that, once internalized, the intruder may be favored even further by being transported around the body by macrophage scavengers, which in turn phagocytose the dead PMNs. In this way, the PMNs become Trojan horses, which might liberate their content of bacteria at times and places that will increase the probability of successful infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Danish Research Council for Technology and Production (26-02-0183).

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 October 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, G. G., J. J. Palermo, J. D. Schilling, R. Roth, J. Heuser, and S. J. Hultgren. 2003. Intracellular bacterial biofilm-like pods in urinary tract infections. Science 301:105-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, P., I. Engberg, G. Lidin-Janson, K. Lincoln, R. Hull, S. Hull, and C. Svanborg. 1991. Persistence of Escherichia coli bacteriuria is not determined by bacterial adherence. Infect. Immun. 59:2915-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann, B. J. 1996. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12, p. 2460-2488. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 4.Caprioli, A., S. Morabito, H. Brugere, and E. Oswald. 2005. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: emerging issues on virulence and modes of transmission. Vet. Res. 36:289-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costerton, J. W., P. S. Stewart, and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diderichsen, B. 1980. flu, a metastable gene controlling surface properties of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 141:858-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diederich, L., L. J. Rasmussen, and W. Messer. 1992. New cloning vectors for integration into the lambda attachment site attB of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Plasmid 28:14-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasman, H., T. Chakraborty, and P. Klemm. 1999. Antigen-43-mediated autoaggregation of Escherichia coli is blocked by fimbriation. J. Bacteriol. 181:4834-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson, I. R., F. Navarro-Garcia, M. Desvaux, R. C. Fernandez, and D. Ala'Aldeen. 2004. Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:692-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isberg, R. R., and G. T. Van Nhieu. 1994. Two mammalian cell internalization strategies used by pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 28:395-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kjaergaard, K., M. A. Schembri, H. Hasman, and P. Klemm. 2000. Antigen 43 from Escherichia coli induces inter- and intraspecies cell aggregation and changes in colony morphology of Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Bacteriol. 182:4789-4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klemm, P., L. Hjerrild, M. Gjermansen, and M. A. Schembri. 2004. Structure-function analysis of the self-recognizing antigen 43 autotransporter protein from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 51:283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi, S. D., J. M. Voyich, and F. R. DeLeo. 2003. Regulation of the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response to infection. Microbes Infect. 5:1337-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehrer, R. I., and T. Ganz. 1990. Antimicrobial polypeptides of human neutrophils. Blood 176:2169-2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochoa, T. J., and T. G. Cleary. 2003. Epidemiology and spectrum of disease of Escherichia coli O157. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16:259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogle, J. D., J. G. Noel, R. M. Sramkoski, C. K. Ogle, and J. W. Alexander. 1988. Phagocytosis of opsonized fluorescent microspheres by human neutrophils. A two-color flow cytometric method for the determination of attachment and ingestion. J. Immunol. Methods. 115:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen, P., M. Meehan, H. de Loughry-Doherty, and I. Henderson. 1996. Phase-variable outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 16:63-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palazzolo, A. M., C. Suquet, M. E. Konkel, and J. K. Hurst. 2005. Green fluorescent protein-expressing Escherichia coli as a selective probe for HOCl generation within neutrophils. Biochemistry 44:6910-6919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roche, A., J. McFadden, and P. Owen. 2001. Antigen 43, the major phase-variable protein of the Escherichia coli outer membrane, can exist as a family of proteins encoded by multiple alleles. Microbiology 147:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schembri, M. A., M. Givskov, and P. Klemm. 2002. An attractive surface: gram-negative bacterial biofilms. Sci. STKE 132:RE6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schembri, M. A., L. Hjerrild, M. Gjermansen, and P. Klemm. 2003. Differential expression of the Escherichia coli autoaggregation factor antigen 43. J. Bacteriol. 185:2236-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherlock, O., U. Dobrindt, J. B. Jensen, R. Munk-Vejborg, and P. Klemm. 2006. Glycosylation of the self-recognizing Escherichia coli Ag43 autotransporter protein. J. Bacteriol. 188:1798-1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherlock, O., M. A. Schembri, A. Reisner, and P. Klemm. 2004. Novel roles for the AIDA adhesin from diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: cell aggregation and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 186:8058-8065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamm, W. E., M. McKevitt, P. L. Roberts, and N. J. White. 1991. Natural history of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svanborg, C., G. Bergsten, H. Fischer, G. Godaly, M. Gustafsson, D. Karpman, A. C. Lundstedt, B. Ragnarsdottir, M. Svensson, and B. Wullt. 2006. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli as a model of host-parasite interaction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ting-Beall, H. P., A. S. Lee, and R. M. Hochmuth. 1995. Effect of cytochalasin D on the mechanical properties and morphology of passive human neutrophils. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23:666-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaudaux, P., and F. A. Waldvogel. 1979. Gentamicin antibacterial activity in the presence of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16:743-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.