Abstract

Thermolysin-like metalloproteinases such as aureolysin, pseudolysin, and bacillolysin represent virulence factors of diverse bacterial pathogens. Recently, we discovered that injection of thermolysin into larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, mediated strong immune responses. Thermolysin-mediated proteolysis of hemolymph proteins yielded a variety of small-sized (<3 kDa) protein fragments (protfrags) that are potent elicitors of innate immune responses. In this study, we report the activation of a serine proteinase cascade by thermolysin, as described for bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), that results in subsequent prophenoloxidase activation leading to melanization, an elementary immune defense reaction of insects. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR analyses of the expression of immune-related genes encoding the inducible metalloproteinase inhibitor, gallerimycin, and lysozyme demonstrated increased transcriptional rates after challenge with purified protfrags similar to rates after challenge with LPS. Additionally, we determined the induction of a similar spectrum of immune-responsive proteins that were secreted into the hemolymph by using comparative proteomic analyses of hemolymph proteins from untreated larvae and from larvae that were challenged with either protfrags or LPS. Since G. mellonella was recently established as a valuable pathogenicity model for Cryptococcus neoformans infection, the present results add to our understanding of the mechanisms of immune responses in G. mellonella. The obtained results support the proposed danger model, which suggests that the immune system senses endogenous alarm signals during infection besides recognition of microbial pattern molecules.

Innate immunity is an evolutionarily conserved system of defense against infections which arose during the evolution of eukaryotic organisms (26, 40). This first line of defense provides the ability to recognize and eliminate pathogens in the body. The discrimination between infectious nonself and noninfectious self is mediated by a limited number of germ line-encoded pattern recognition receptors which bind to microbial components, such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycans, and fungal β-1,3-glucans (2, 22, 41). In contrast, the adaptive or acquired immunity represents a novel evolutionary feature of vertebrates. The latter mediates the highly specific recognition of a wide range of antigens by a large and diverse spectrum of somatically rearranged receptors of T and B cells that are absent from invertebrates (2). The adaptive immune system provides specific recognition of pathogen-associated antigens, immunological memory of infection, and pathogen-specific antibodies.

The complex cross talk between the innate and the adaptive immune system in vertebrates is difficult to analyze (7, 17). Therefore, invertebrates lacking adaptive immunity have been adopted as models to investigate the interactions of pathogens with the innate immune system at the molecular level. Our rapidly increasing knowledge about the ancient innate immune system has profited from the successful establishment of genetically tractable animal models with a completely sequenced genome, such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (20) and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (38). Comparative molecular analysis of genes and gene products dramatically increased the number of homologues for immune-related genes and signaling pathways that were first identified in Drosophila and then in humans or vice versa (20). However, other insect species are currently emerging as models with distinct advantages for dissecting the interactions of human pathogens with the innate immune system (15, 16, 25, 41).

One lepidopteran model in particular, the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, attracts attention because this species can be reared at temperatures to which human pathogens are adapted and which are essential for the production of many microbial toxins (16). For example, G. mellonella was recently established as a suitable host model to study the pathogenesis of bacterial and yeast species causing diseases in humans, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (34), Staphylococcus aureus (16), Bacillus cereus (14), Cryptococcus neoformans (39), and Candida albicans (6, 10).

Among the enzymes associated with human pathogenic bacteria and fungi, thermolysin-like metalloproteinases seem to play a predominant role during pathogenesis and cause increases in vascular permeability, hemorrhagic edema, and sepsis (31, 35). They promote development within the infected host, and they are used to suppress or avoid its innate immune system (21, 23, 35, 36, 37, 48). Since particular metalloproteinases associated with human pathogens have been recognized as prominent virulence factors, their therapeutic inhibition has become a novel strategy in the development of second-generation antibiotics (43, 45).

Interestingly, G. mellonella is the first and to date only animal from which a specific peptidic inhibitor of microbial metalloproteinases has been reported (50). Functional studies with the recombinant inducible metalloproteinase inhibitor (IMPI) confirmed that it inhibits thermolysin-like microbial metalloproteinases (13). The IMPI gene encodes two distinct metalloproteinase inhibitors that putatively contribute to the regulation of metalloproteinases associated with invading pathogens (51). The presence and activity of microbial metalloproteinases within the body of G. mellonella result in the generation of a variety of small-sized (<3 kDa) protein fragments (protfrags) which are potent elicitors of innate immune responses (18). In this study, we used G. mellonella larvae to explore the role of microbial metalloproteinases in sensing infection and activation of innate immune responses. We demonstrate that the expression rates of several immune-related genes that we previously identified by comparative immune-related transcriptomic analyses (42) are increased after challenge with purified protfrags, similar to the expression rates after challenge with LPS. In a complementary approach, we report here proteomic analyses of hemolymph samples from last-instar larvae that were challenged either with LPS or with protfrags. The obtained results lend some credit to our hypothesis that microbial metalloproteinases mediate sensing of invading pathogens and activate innate immune responses in G. mellonella. Besides induced expression and secretion of immune-related proteins after injections with protfrags, we provide evidence that thermolysin activates the prophenoloxidase-activating cascade leading to melanization, which is an important invertebrate defense mechanism for entrapping microbes and parasites (12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insects.

Galleria mellonella larvae were reared on an artificial diet (22% maize meal, 22% wheat germ, 11% dry yeast, 17.5% bee wax, 11% honey, and 11% glycerin) at 31°C in darkness.

Generation of protfrags and characterization by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Collection of cell-free hemolymph samples from last-instar larvae of G. mellonella, their digestion with thermolysin, and preparation of immune-stimulatory hemolymph protfrags was performed as previously described in detail (18). In order to characterize the obtained protfrags in more detail, we performed a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometric analysis. Two microliters of the sample was prepared onto a stainless steel template, and immediately, 1 μl of matrix (10 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in water-acetonitrile (1:1) with 0.03% trifluoroacetic acid) was added. The sample-matrix mixture was air dried at room temperature. Positive ion mass spectra were recorded using a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Voyager DE-PRO; Applied Biosystems) equipped with a reflectron, post-source decay, and collision-induced dissociation options. Mass spectra were obtained from 400 to 20,000 Da. All analyses were carried out in the linear and delayed extraction mode. Bovine serum albumin products were used for external calibration.

Immunization of G. mellonella larvae.

Last-instar larvae, each weighing between 250 and 350 mg, were used for immunization using the following solutions: H2O, 10 mg/ml LPS (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany), 10 mg/ml Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10 mg/ml Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), and protfrags (10 μl is equivalent to 5 μl thermolysin-generated hemolymph protein fragments with a molecular mass below 3,000 Da). E. coli and S. cerevisiae were heat inactivated for 30 min at 60°C prior to application. Ten microliters of sample volume per larva was injected dorsolaterally into the hemocoel using 1-ml disposable syringes and 0.4- by 20-mm needles mounted on a microapplicator. Larvae were homogenized at 8 h postinjection for RNA isolation or bled at 24 h postinjection to obtain hemolymph samples.

PPO activity assay.

Prophenoloxidase (PPO) activity assays were performed in 96-well microtiter plates. In each well, 50 μl of elicitor (thermolysin or LPS diluted in 20 mM NaHPO4, pH 7.4) was mixed with 40 μl of freshly prepared hemolymph (1:10 diluted in 20 mM NaHPO4, pH 7.4) and with 10 μl of 25 mM 3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine (Sigma). The absorbance at 512 nm was measured over a period of 30 min at 22°C in an EL 808 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

The transcriptional levels of IMPI, gallerimycin, lysozyme, and actin genes were determined with the real-time PCR system Mx3000P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using FullVelocity SYBR green QRT-PCR master mix (Stratagene), purified RNA, and the appropriate primers in a manner similar to that described previously (4).

Antibacterial activity assays.

Antibacterial activity was measured by a inhibition zone assay using a lipopolysaccharide-defective, streptomycin- and ampicillin-resistant mutant of the E. coli K-12 strain D31 (8). In brief, petri dishes (diameter, 100 mm) were filled with 7 ml of E. coli suspension, containing 2× YT (16 g/liter tryptone, 10 g/liter yeast extract, and 5 g/liter NaCl [pH 7.0]) nutrient broth (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), 1% high-purity agar-agar (Carl Roth), and 2 × 104 viable bacteria in logarithmic growth phase. Holes with a diameter of 4 mm were punched into the agar and filled with 3 μl of cell-free hemolymph. The diameters of the clear zones were measured after 24 h of incubation at 37°C and the number of units/ml was calculated using a calibration curve obtained with dilutions of gentamicin (Sigma).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of hemolymph proteins.

Cell-free hemolymph samples were isolated by bleeding injected larvae at 24 h postinjection, or untreated larvae, into plastic tubes with traces of phenylthiourea, followed by a centrifugation step of the hemolymph at 5,000 × g for 5 min. The hemolymph was precipitated by the addition of 3 volumes of 100% acetone and 0.4 volumes of 100% trichloroacetic acid and incubation at −20°C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min, the pellet was washed three times with 100% acetone and resolved under agitation in 8 M urea at 22°C for 16 h. Protein concentrations were determined using a Micro BC assay kit (Uptima, Montlucon, France).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was performed with the Ettan IPGphor II system and the Ettan DALTsix electrophoresis unit (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 1 mg of protein was mixed with immobilized pH gradient (IPG) buffer (pH 3 to 11 nonlinear gradient [NL]) and applied on an IPG strip (24 cm; pH 3 to 11 NL). Isoelectric focusing was performed at 20°C and 75 μA per IPG strip as follows: reswelling for 24 h and isoelectric focusing for 1 h at 500 V, 8-h gradient to reach 1,000 V, 3-h gradient to reach 8,000 V, and isoelectric focusing for 4 h at 8,000 V. Prior to Tris-Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5) with 26- by 20-cm 15% gels, the strips were equilibrated with 6 M urea, 30% glycerin, 2% SDS, and 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8. After electrophoresis at 20°C, the gels were stained using colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue (Carl Roth). For image analysis, the gels were scanned using a Umax PowerLook II scanner and analyzed with Delta2D software (Decodon, Greifswald, Germany).

In-gel digestion and protein identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Spots excised from the gel were carbamidomethylated and in-gel digested using mass spectrometry grade trypsin (Promega) in 0.025 M NH4HCO3. The mass spectra of the resulting tryptic peptides were recorded using an Ultraflex TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany) operating under FlexControl 2.4 (Bruker) in the positive-ion reflectron mode, with dihydroxy benzoic acid as the matrix. Peptide mass profiles were analyzed with Mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com), using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database.

N-terminal protein sequencing.

Proteins were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Carl Roth) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, and the N-terminal sequences were determined by automated Edman degradation using an Applied Biosystems 492 pulsed liquid-phase sequencer equipped with an on-line 785A phenylthiohydantoin derivative analyzer.

Protein identification using degenerated primers and 3′ RACE PCR for isolation of the corresponding cDNA.

Total RNA was extracted from larvae using Tri Reagent isolation reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). Purified RNA was used for reverse transcription of mRNA with oligonucleotide Race-T7-dT17-primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) and StrataScript reverse transcriptase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. In order to PCR amplify the cDNA sequences of the protein spots with determined N-terminal protein sequences, degenerated oligonucleotides were constructed and used in combination with T7 primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) corresponding to the 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) PCR technique. In the case of protein spot 23, the oligonucleotide spot23-degen-for (5′-ATHGAYGGIAARGAYTAYCCITTYCCITTY-3′ [R = A or G; Y = C or T; H = A, C, or T; I = inosine]) was used. PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 20 μl using a PCR cycler (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) with a heated lid and the ReadyMix PCR system (Sigma). An initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min was followed by 20 cycles of a drop-down PCR with denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 50°C minus 0.75°C after every cycle for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. Afterwards, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 42°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s were performed. A final 10-min 72°C step was added to allow complete extension of the products. The resulting PCR products were separated on 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining according to standard procedures (5), and the amplificate was isolated by excising the corresponding gel piece. Subsequently, the amplificate was ligated into pCRT7/CT-TOPO (Invitrogen) and transformed into TOP10F′ cells (Invitrogen). Colonies were screened by using a FastPlasmid miniprep kit (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), followed by XbaI and HindIII digestion of isolated plasmids and analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis. Positive colonies were custom sequenced by GENterprise GmbH (Mainz, Germany).

RESULTS

Thermolysin-mediated serine proteinase cascade activation leading to PPO activation.

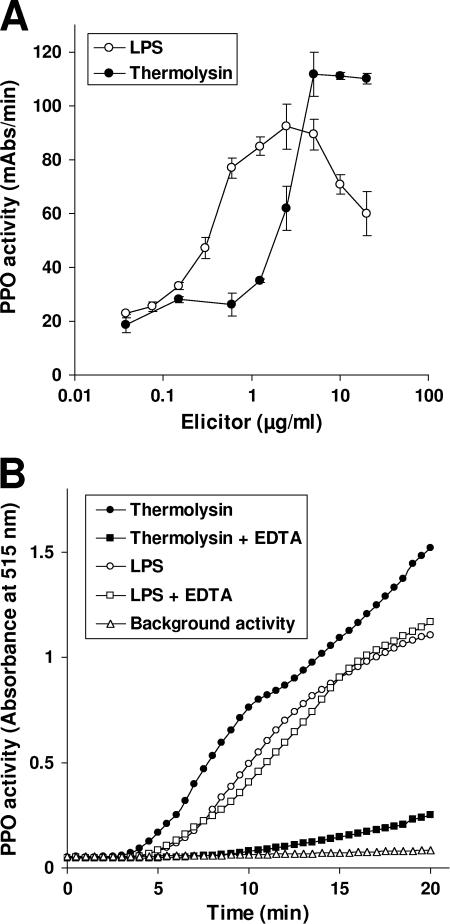

In order to characterize the activation of the immune response in G. mellonella by thermolysin in more detail, we analyzed PPO activation in comparison with activation by LPS. As described before (27), the latter was found to be a strong elicitor of PPO activity, with a maximal induction at LPS concentrations between 0.5 and 10 μg/ml of approximately three- to fourfold above basal level (Fig. 1A). The induction of PPO activity by thermolysin was detected at concentrations starting at 1.25 μg/ml and reaching maximal induction levels of over fivefold at concentrations above 5 μg/ml (Fig. 1A). LPS exhibited a bell-shaped concentration-dependent PPO activation curve that is characteristic of a template-dependent mechanism of enzyme activation (Fig. 1A), as described for the activation of serine proteinases involved in human hemostasis (3). In contrast, thermolysin exhibited a saturable concentration-dependent PPO activation curve indicative of proteolytic activation of one or more serine proteinases. This is in agreement with the finding that EDTA, which inhibits the proteolytic activity of thermolysin by chelating the catalytical zinc ion, significantly decreases the induction of PPO activation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, EDTA had no significant influence on LPS-stimulated PPO activation (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of PPO activity in the presence of LPS and thermolysin. (A) The PPO activity of pooled hemolymph from G. mellonella larvae was analyzed in the presence of increasing concentrations of the elicitors LPS and thermolysin. PPO activity is expressed as substrate 3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine oxidation at maximal reaction velocity (milli-absorbance [mAbs]/min). Results represent mean values from at least three independent determinations ± standard deviations. (B) The PPO activity was analyzed in the presence of 5 μg/ml LPS or thermolysin, which was found to be the concentration for the highest PPO activation by both elicitors. PPO activation by thermolysin was nearly abolished in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. In contrast, PPO activation by LPS was not influenced by the presence of 10 mM EDTA. Results represent a typical experiment out of multiple independently performed experiments.

Thermolysin-mediated hemolymph protein hydrolysis.

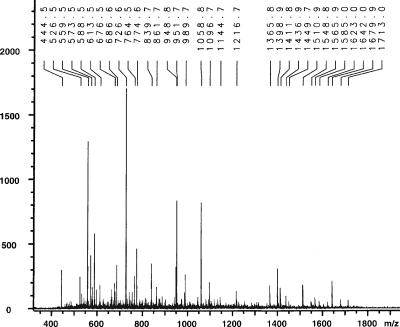

Mass spectrometric analysis of the purified protfrags resulted in numerous peptides with molecular masses between 400 and 1,800 Da that were absent in control preparations of nondigested cell-free hemolymph (Fig. 2). To analyze whether a single or numerous peptides are responsible for immune stimulatory activity, we fractionized the protfrag sample by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Several fractions exhibited immune stimulatory activity when injected into larvae (data not shown), implicating that not a single but rather a number of distinct peptides are responsible for immune stimulation. Because we lacked a sequenced genome of G. mellonella and because of the limits that some peptides were glycosylated or otherwise modified, we were unable to further characterize the hemolymph protein fragments.

FIG. 2.

Characterization of the purified protfrags by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The m/z values of the most prominent peptides are indicated.

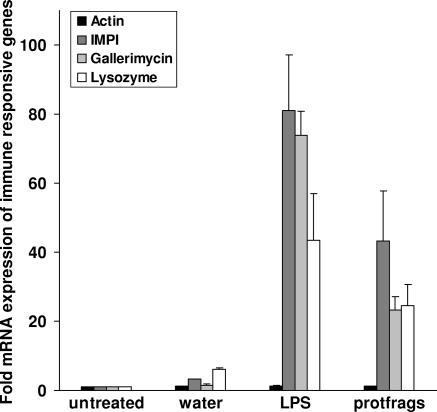

Protfrags and LPS induced expression of immune-responsive genes.

In order to estimate the immune stimulatory activity of protfrags in comparison to that of LPS, we injected the corresponding solutions into last-instar larvae of G. mellonella and determined the expression of genes encoding lysozyme, which is involved in antibacterial and antifungal defense in G. mellonella (46), gallerimycin, a cysteine-rich defensin-like antifungal protein (28), and the IMPI (13) by using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The transcriptional rate of the housekeeping gene actin was analyzed as a reference and showed no significant differences following the indicated treatments (Fig. 3). In contrast, strongly enhanced lysozyme, gallerimycin, and IMPI expression in response to injected LPS or protfrags was observed. Whereas the injection of water resulted in 2- to 6-fold increased transcription rates of the immune-responsive genes due to the wounding reaction, 100 μg LPS per larva and 10 μl protfrags per larva, corresponding to 5 μl hemolymph fragments (<3 kDa), resulted in 40- to 80-fold and 23- to 45-fold induction, respectively (Fig. 3). Quantification of antimicrobial activity against E. coli with the inhibition zone assay confirmed that 10 μl protfrags per larva induces an immune response similar to that induced by 10 μg LPS or 100 μg heat-inactivated E. coli per larva (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

LPS and protfrags induced transcriptional levels of immune-responsive genes in larvae of G. mellonella. The transcription levels of IMPI, gallerimycin, and lysozyme in larvae injected with water, LPS, or protfrags are shown relative to their expression levels in untreated larvae. The transcription level of the housekeeping gene actin was not significantly influenced by the treatments. Results represent mean values from at least three independent determinations ± standard deivations.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of antibacterial activity of hemolymph of G. mellonella larvae after injection of several immune response elicitors. The antibacterial activities represented by gentamicin equivalents in the hemolymph of larvae injected with water, 100 μg heat-inactivated yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), 100 μg heat-inactivated E. coli, 10 μl protfrags, 10 μg LPS, and 100 μg LPS, respectively, are shown in comparison to the level of untreated larvae. Results represent mean values from three independent determinations ± standard deviations. For each determination, pooled hemolymph from five larvae was used.

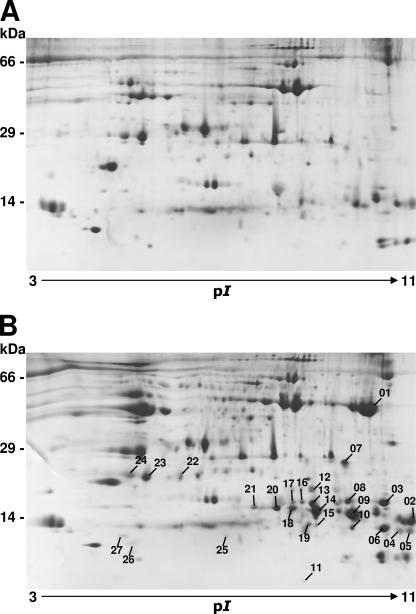

Proteomic analysis of hemolymph proteins after immune challenge.

To separate and identify proteins that are induced and secreted within the hemolymph upon injection of either LPS or protfrags, we used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis combined with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, along with Edman sequencing, to further ascertain the identity of these peptides. Because antimicrobial peptides are, in general, cationic (in rare cases anionic) and have molecular masses between 4 and 40 kDa (11), we used IPG strips that separate proteins with pI values of 3 to 11 and a 15% Tris-Tricine-SDS gel that is best for separating proteins with a low molecular weight. Indeed, 20 of 27 protein spots that were strongly induced after immune challenge exhibited pI values of 6.5 to 11 and molecular masses of 8 to 25 kDa (Fig. 5A and B). Picked protein spots were subjected to peptide mass fingerprinting by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, and four spots were additionally protein sequenced by Edman degradation. The analysis and identity of the proteins are summarized in Table 1. Besides lysozyme, we found some other proteins involved in innate immunity, including several isoforms of the antibacterial peptide gloverin, which has been reported only for G. mellonella and other lepidopteran species (42), apolipophorin III, peptidylprolyl isomerase, and gluthathione S-transferase. It should be noted that we can only be sure about the identity of peptides that are present in public databases and originate from G. mellonella. For example, spot 6 was identified as a gloverin-like protein by a BLASTP search at NCBI databases but not by peptide mass fingerprinting. For spot 23, we were able to identify the protein as peptidoglycan recognition protein LB (PGRP-LB) after isolation of its corresponding cDNA by a 3′ RACE PCR using a constructed degenerate primer of the N-terminal sequence that was obtained by Edman degradation. The sequence was deposited at EMBL with the accession number AM392402. In the case of spot 10 and spot 14, which differ only in a single amino acid in the determined N-terminal sequences, we could not successfully amplify the corresponding cDNAs. Additionally, we identified PGRP-A plus one isoform and PGRP-B in the immune hemolymph of G. mellonella larvae. PGRPs are evolutionarily conserved receptors of peptidoglycans, which mediate sensing of microbes and modulate innate immune responses (52). Since similar protein spot patterns were derived following protfrag or LPS challenge (Fig. 6), we think that similar signaling pathways were activated by both elicitors to induce comparable spectrums of proteins during innate immune response.

FIG. 5.

Two-dimensional map of G. mellonella hemolymph proteins. Hemolymph protein (1 mg) from 30 untreated (A) and 30 LPS-immunized (B) larvae was loaded on 24-cm pH 3 to 11 NL isoelectric focusing strips, followed by Tris-Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 15% gel. Twenty-seven out of approximately 620 abundant hemolymph proteins strongly induced after immune challenge were identified and analyzed by peptide mass fingerprinting. In addition, four spots were analyzed by N-terminal protein sequencing. Molecular mass standards are indicated in kDa, and the pI range is indicated by an arrow.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of immune-induced proteins obtained by comparative two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

| Spot | Edman sequence | Identified protein (organism) | NCBI/EMBL accession no. | Expect value | % Sequence coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fe-S protein 8 (Bombyx mori) | ABD36237 | 11 | 34 | |

| 2 | Lysozyme (G. mellonella) | P82174 | 160 | 29 | |

| 3 | PGRP-B (G. mellonella) | AAN15786 | 0.14 | 74 | |

| 4 | |||||

| 5 | Gloverin-like protein (G. mellonella) | Q8ITT0 | 130 | 59 | |

| 6a | DVTRDKQVGKGK | Gloverin-like protein 4 (B. mori) | BAD51476 | ||

| 7 | |||||

| 8 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase (B. mori) | ABF51321 | 190 | 36 | |

| 9 | Apolipophorin III (G. mellonella) | P82174 | 11 | 28 | |

| 10 | DLSVDKKTGDVTLDH | ||||

| 11 | |||||

| 12 | |||||

| 13 | |||||

| 14 | DLSVDKKTED | ||||

| 15 | Cellular retinoic acid binding protein (B. mori) | ABD36292 | 60 | 43 | |

| 16 | |||||

| 17 | |||||

| 18 | Glutathione S-transferase 5 (B. mori) | ABC79692 | 100 | 20 | |

| 19 | |||||

| 20 | PGRP-A (G. mellonella) | AAN15782 | 1.2 | 68 | |

| 21 | PGRP-A (G. mellonella) | AAN15782 | 7.6 | 82 | |

| 22 | |||||

| 23b | XPSXXIDGKDYPFPF | PGRP-LB (G. mellonella) | AM392402 | ||

| 24 | |||||

| 25 | |||||

| 26 | |||||

| 27 |

Identified by BLASTP search with the N-terminal sequence.

Identified by 3′ RACE PCR with a degenerated primer of the N-terminal sequence.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of two-dimensional gel sections of hemolymph proteins from protfrag-challenged, LPS-challenged, and untreated larvae. Sections of two-dimensional gels of hemolymph proteins from (A) untreated, (B) LPS-injected, and (C) protfrag-injected larvae were compared. LPS and protfrag challenges resulted in similar patterns of spots, suggesting similar immune responses. The identified protein spots are indicated by circles. Molecular mass standards are indicated in kDa, and the pI range is indicated by an arrow. GST-5, glutathione S-transferase 5; PPI, peptidylprolyl isomerase; Apo III, apolipophorin III.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support our hypothesis that particular microbial metalloproteinases mediate sensing of invading microbes and elicit innate immune responses in insects. Thermolysin-like metalloproteinases associated with human or entomopathogenic bacteria and fungi play a predominant role as virulence factors and promote their development within the infected host (35, 48). The lepidopteran G. mellonella has been established as a model in research of the interactions between fungal pathogens and the insect innate immune system (47) and was used to investigate sensing of invading microbes via their associated metalloproteinases, whose nonregulated activity within the hemolymph generates immune stimulatory hemolymph protein fragments (18). Here, we provide mass spectrometric analysis of the protfrags, corresponding to the ultrafiltrate obtained after thermolysin-mediated hemolymph hydrolysis. A number of peptides have been identified that were absent in control preparations of nondigested cell-free hemolymph. Lacking a completely sequenced genome of G. mellonella and the presence of glycosylated or otherwise modified hemolymph protein fragments, we were unable to further characterize the individual peptides. In a recent study, we provided evidence that thermolysin-mediated digestion of the extracellular matrix component collagen IV but not of laminin or fibronectin generates particular fragments of similar molecular masses that induce expression of lysozyme, gallerimycin, and the IMPI when injected (4). Since collagen IV, the only known collagen from insects (30), has been reported to be involved in lepidopteran innate immunity (1) and collagenases or collagen-degrading enzymes associated with pathogens play a key role during infection (19), it has become a favorite substrate whose breakdown by microbial metalloproteinases mediates sensing of the latter (4). The aim of the present study was to demonstrate that thermolysin-mediated processing of hemolymph proteins generates peptidic fragments which elicit innate immune responses that are quantitatively (expression level of antimicrobial peptides) and qualitatively (spectrum of immune-related proteins secreted into the hemolymph) comparable with the response to injected LPS.

Protfrags and LPS induced expression of a similar spectrum of immune-related genes encoding antimicrobial peptides, such as gallerimycin, gloverin, IMPI, and lysozyme. Interestingly, we identified also PGRP-A and PGRP-B, which mediate sensing of invading microbes, PGRP-LB, which is an important modulator of the immune response to bacterial infection in Drosophila (52), and miscellaneous other proteins associated with defense against infections. Some of the latter were recently reported to be also induced after Candida infection in G. mellonella (apolipophorin III, peptidylprolyl isomerase, and glutathione S-transferase) (6). Relative quantification of mRNA encoding lysozyme, gallerimycin, and the IMPI by using quantitative real-time RT-PCR, along with the content of proteins in spots identified in proteomic analyses, indicated that protfrags may exhibit a lesser immune stimulatory activity than LPS, but it should be mentioned that 100 μg LPS per larva, corresponding to approximately 400 mg per kg body weight, was used in this study to induce a very strong immune response. Lower concentrations of LPS were found to induce weaker immune responses (Fig. 4). During natural infection, several elicitors may contribute to the immune response. However, we believe that hemolymph protein degradation by microbial metalloproteinases plays an important role in sensing of infectious nonself and in activation of innate immune activation. This hypothesis is further supported by the documented thermolysin-mediated serine proteinase cascade activation leading to PPO activation and melanization, which is a conserved host defense reaction in insects and other arthropods, such as the mosquito, where it is a critical determinant of resistance to the malarial parasite (49). It should be noted here that the melanization reaction does not appear to be critical for survival of Drosophila after bacterial or fungal infection (29) but that it plays a critical role in enhancing the effectiveness of other immune reactions in Drosophila during infection (44). In the present study, thermolysin activates the PPO cascade in a saturable, concentration-dependent manner, suggesting a direct activation of one or more serine proteinases by hydrolysis. On the other hand, LPS exhibited a bell-shaped concentration-dependent PPO activation curve that is characteristic of a template-dependent mechanism of enzyme activation, as described for the activation of serine proteinases involved in human hemostasis (3).

Our results allow the conclusion that the recognition system for a microbial pattern in G. mellonella is capable of sensing both microbial cell wall components, such as bacterial LPS, and endogenous immune stimulatory peptides generated by microbial metalloproteinases. The latter are reportedly associated with entomopathogenic viruses, bacteria, and fungi, where they promote development within the infected insect host in a multifaceted manner (9, 48). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that pathogen resistance in insects is synergistically conferred by an ability to sense microbial proteinases and to produce a set of inhibitors that are secreted within the hemolymph along with other antimicrobial peptides.

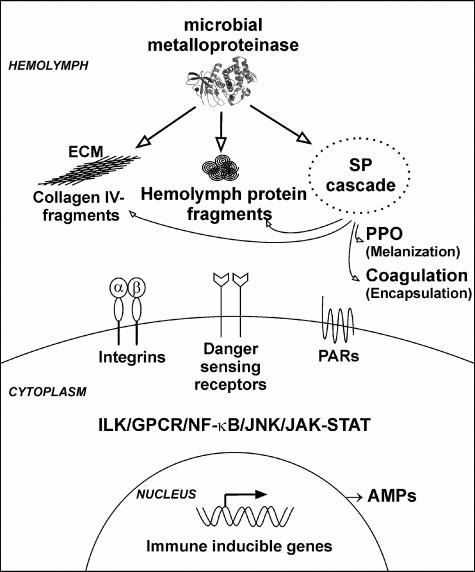

G. mellonella has become a favorite model for studying the pathogenesis of human pathogens in a nonmammalian model, because this species can be reared at higher temperatures than other model insects such as Drosophila. To date, G. mellonella has been used to study the etiology of infection and immunity against the bacterial human pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa (34), Bacillus cereus (14), and Staphylococcus aureus (16) and also the yeasts Cryptococcus neoformans (39) and Candida albicans (6, 10). The results presented in this study provide novel insights into microbial sensing and activation of innate immunity in G. mellonella, particularly thermolysin-mediated activation of the serine proteinase cascade, which controls PPO activation. Peptidic fragments derived from hemolymph proteins or collagen IV serve as danger signals triggering a set of signaling pathways that lead to the induced expression of immune-related genes (Fig. 7). Our findings may bridge two widely accepted models about immunity. The infectious nonself model postulates that the immune system is set into alarm by recognition of microbial pattern molecules which are absent from the host, e.g., microbial cell wall components, whereas the so-called danger model suggests that the immune system is more concerned with entities that do damage than with those that are foreign. The danger model explains the activation of immune responses by danger/alarm signals from injured cells, such as those exposed to pathogens, toxins, or mechanical damage (32). Our results support the hypothesis that pattern recognition of infectious nonself in G. mellonella encompasses sensing of microbial metalloproteinases that generate danger/alarm signals during infection. These findings are in agreement with recent insights into the links between microbial infection, chronic inflammation, and cancer in murine models. The Toll-like receptors involved in pattern recognition and activation of macrophage inflammatory responses bind to ligands of microbial origin, such as LPS, flagellin, β-glucans, and lipopeptides, but also to endogenously derived ligands, such as heat shock protein 70, chromatin component HMG-B1, and cellular RNA and DNA (24). Additionally, intracellular pattern recognition receptors have also been identified in mammals that sense microbial molecules as well as host-derived danger signals, such as uric acid crystals (33). Based on the principle of mutual elucidation, we are convinced that further comparative studies of the lepidopteran host model G. mellonella will also promote our knowledge about evolutionarily conserved features of vertebrate immunity.

FIG. 7.

Proposed danger model describing the sensing of protein fragmentation by microbial metalloproteinases and activation of innate immune responses in G. mellonella. Microbial metalloproteinases (e.g., thermolysin; three-dimensional structure based on Protein Data Bank accession no. 1KEI) associated with invading pathogens digest hemolymph proteins, resulting in the formation of small peptidic fragments that bind to yet unidentified receptors (danger-sensing receptors). The engagement of these receptors triggers signaling pathways which lead to the expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), such as lysozyme, gallerimycin, and IMPI. Recently, we showed that fragments of the extracellular matrix (ECM) component collagen IV stimulate innate immune response in G. mellonella (4). It is obvious that several small collagen IV fragments possess RGD sequence motifs that are responsible for integrin binding. The proven activation of the serine proteinase (SP) cascade in the hemolymph by thermolysin results in PPO activation and melanization and may also be involved in the coagulation and receptor activation of proteinase-activated receptors (PARs). In summary, the following signaling pathways may be involved in danger sensing: the well-known NF-κB, Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK), and JAK-STAT pathways of the insect immune responses, the integrin-dependent signaling pathways via integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and, in the case of PARs, the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) pathways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meike Fischer, Hans Günter Welker, and Peter Dotzauer (Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen, Germany) for excellent technical assistance, Alexandr Jegorov (Galena, Czech Republic) for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of the protfrags, and Rod Snowdon (Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen, Germany) and Katja Altincicek (Giessen, Germany) for critical reading of the manuscript.

We acknowledge financial support from the Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen to B.A. and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A.V.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, T., M. Tomita, and K. Yoshizato. 2005. Synthesis of prolyl 4-hydroxylase α subunit and type IV collagen in hemocytic granular cells of silkworm, Bombyx mori: involvement of type IV collagen in self-defense reaction and metamorphosis. Matrix Biol. 24:136-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira, S., S. Uematsu, and O. Takeuchi. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altincicek, B., A. Shibamiya, H. Trusheim, E. Tzima, M. Niepmann, D. Linder, K. T. Preissner, and S. M. Kanse. 2006. A positively charged cluster in the epidermal growth factor-like domain of Factor VII-activating protease (FSAP) is essential for polyanion binding. Biochem. J. 394:687-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altincicek, B., and A. Vilcinskas. 2006. Metamorphosis and collagen-fragments activate innate immune responses in the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 30:1108-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- 6.Bergin, D., L. Murphy, J. Keenan, M. Clynes, and K. Kavanagh. 2006. Pre-exposure to yeast protects larvae of Galleria mellonella from a subsequent lethal infection by Candida albicans and is mediated by the increased expression of antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect. 8:2105-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutler, B., Z. Jiang, P. Georgel, K. Crozat, B. Croker, S. Rutschmann, X. Du, and K. Hoebe. 2006. Genetic analysis of host resistance: Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24:353-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boman, H. G., I. Nilsson-Faye, K. Paul, and T. Rasmuson, Jr. 1974. Insect immunity. I. Characteristics of an inducible cell-free antibacterial reaction in hemolymph of Samia cynthia pupae. Infect. Immun. 10:136-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen, D., T. Rocheleau, C. Grutzmacher, L. Meslet, M. Valens, D. Marble, A. Dowling, R. ffrench-Constant, and M. A. Blight. 2003. Genetic and biochemical characterization of PrtA, an RTX-like metalloprotease from Photorhabdus. Microbiology 149:1581-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan, M., D. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and K. Kavanagh. 2002. Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 13:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulet, P., and R. Stöcklin. 2005. Insect antimicrobial peptides: structures, properties and gene regulation. Protein Pept. Lett. 12:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerenius, L., and K. Söderhäll. 2004. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 198:116-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clermont, A., M. Wedde, V. Seitz, L. Podsiadlowski, M. Hummel, and A. Vilcinskas. 2004. Cloning and expression of an inhibitor against microbial metalloproteinases from insects (IMPI) contributing to innate immunity. Biochem. J. 382:315-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedhila, S., N. Daou, D. Lereclus, and C. Nielsen-Leroux. 2006. Identification of Bacillus cereus internalin and other candidate virulence genes specifically induced during oral infection in insects. Mol. Microbiol. 62:339-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs, B. B., and E. Mylonakis. 2006. Using non-mammalian hosts to study fungal virulence and host defense. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Lara, J., A. Needham, and S. Foster. 2005. Invertebrates as animal models for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis: a window into host-pathogen interaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germain, R. N. 2004. An innately interesting decade of research in immunology. Nat. Med. 10:1307-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griesch, J., M. Wedde, and A. Vilcinskas. 2000. Recognition and regulation of metalloproteinase activity in the hemolymph of Galleria mellonella: a new pathway mediating induction of humoral immune responses. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30:461-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrington, D. J. 1996. Bacterial collagenases and collagen-degrading enzymes and their potential role in human disease. Infect. Immun. 64:1885-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann, J. 2003. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature 426:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung, C.-Y., K. Seshan, J. J. Yu, R. Schaller, J. Xue, V. Basrur, M. Gardner, and G. Cole. 2005. A metalloproteinase of Coccidioides posadasii contributes to evasion of host detection. Infect. Immun. 73:6689-6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janeway, C., and R. Medshitov. 2002. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:197-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin, F., O. Matsushita, S.-I. Katayama, S. Jin, C. Matsushita, J. Minami, and A. Okabe. 1996. Purification, characterization, and primary structure of Clostridium perfringens lambda-toxin, a thermolysin-like metalloprotease. Infect. Immun. 64:230-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karin, M., T. Lawrence, and V. Nizet. 2006. Innate immunity gone awry: linking microbial infections to chronic inflammation and cancer. Cell 124:823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavanagh, K., and E. Reeves. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimbrell, D., and B. Beutler. 2001. The evolution and genetics of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:256-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopácek, P., C. Weise, and P. Götz. 1995. The prophenoloxidase from the wax moth Galleria melonella: purification and characterization of the proenzyme. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 25:1081-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langen, G., J. Imani, B. Altincicek, G. Kieseritzky, K. H. Kogel, and A. Vilcinskas. 2006. Transgenic expression of gallerimycin, a novel antifungal insect defensin from the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella, confers resistance against pathogenic fungi in tobacco. Biol. Chem. 387:549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leclerc, V., N. Pelte, L. El Chamy, C. Martinelli, P. Ligoxygakis, J. A. Hoffmann, and J. M. Reichhart. 2006. Prophenoloxidase activation is not required for survival to microbial infections in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 7:231-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lunstrum, G. P., H. P. Bachinger, L. I. Fessler, K. G. Duncan, R. E. Nelson, and J. H. Fessler. 1988. Drosophila basement membrane procollagen IV. I. Protein characterization and distribution. J. Biol. Chem. 263:18318-18327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda, H. 1996. Role of metalloproteinases in pathogenesis. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:685-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matzinger, P. 2002. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science 296:301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meylan, E., J. Tschopp, and M. Karin. 2006. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature 442:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyata, S., M. Casey, D. W. Frank, F. M. Ausubel, and E. Drenkard. 2003. Use of the Galleria mellonella caterpillar as a model host to study the role of the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 71:2404-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyoshi, S.-I., and S. Sinoda. 2000. Microbial metalloproteases and pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyoshi, S.-I., H. Nakazawa, K. Kawata, K. I. Tomochika, K. Tobe, and S. Shinoda. 1998. Characterization of the hemorrhagic reaction caused by Vibrio vulnificus metalloproteinase, a member of the thermolysin family. Infect. Immun. 66:4851-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyoshi, S.-I., Y. Sonoda, H. Wakiyama, M. Rahman, K. Tomochika, S. Shinoda, S. Yamamoto, and K. Tobe. 2002. An exocellular thermolysin-like metalloproteinase produced by Vibrio fluvialis: purification, characterization, and gene cloning. Microb. Pathog. 33:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mylonakis, E., and A. Abally. 2005. Worms and flies as genetically tractable animal models to study host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 73:3833-3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mylonakis, E., R. Moreno, J. El Kohoury, A. Idnurm, J. Heitmann, S. Calderwood, F. Ausubel, and A. Diener. 2005. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogensis. Infect. Immun. 73:3842-3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nürnberger, T., F. Brenner, B. Kemmerling, and L. Piater. 2001. Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunol. Rev. 198:219-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Royet, J. 2004. Infectious non-self recognition in invertebrates: lessons from Drosophila and other insect models. Mol. Immunol. 41:1063-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seitz, V., A. Clermont, M. Wedde, M. Hummel, A. Vilcinskas, K. Schlatterer, and L. Podsiadlowski. 2003. Identification of immunorelevant genes from greater wax moth (Galleria mellonella) by a subtractive hybridization approach. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 25:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Supuran, C., A. Scozzafava, and A. Mastrolorenzo. 2001. Bacterial proteases: current therapeutic use and future prospects for the development of new antibiotics. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 11:221-259. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang, H., Z. Kambris, B. Lemaitre, and C. Hashimoto. 2006. Two proteases defining a melanization cascade in the immune system of Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28097-28104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Travis, J., and J. Potempa. 2000. Bacterial proteinases as targets for development of second-generation antibiotics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1477:35-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vilcinskas, A., and V. Matha. 1997. Antimycotic activity of lysozyme and its contribution to antifungal humoral defense reactions in Galleria mellonella. Anim. Biol. 6:13-23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vilcinskas, A., and P. Götz. 1999. Parasitic fungi and their interactions with the insect immune system. Adv. Parasitol. 43:267-313. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vilcinskas, A., and M. Wedde. 2002. Insect inhibitors of metalloproteinases. IUBMB Life 54:339-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volz, J., H. M. Muller, A. Zdanowicz, F. C. Kafatos, and M. A. Osta. 2006. A genetic module regulates the melanization response of Anopheles to Plasmodium. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1392-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wedde, M., C. Weise, P. Kopacek, P. Franke, and A. Vilcinskas. 1998. Purification and characterization of an inducible metalloprotease inhibitor from the hemolymph of greater wax moth larvae, Galleria mellonella. Eur. J. Biochem. 255:534-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wedde, M., C. Weise, C. Nuck, B. Altincicek, and A. Vilcinskas. The insect metalloproteinase inhibitor gene of the lepidopteran Galleria mellonella encodes for two distinct inhibitors. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Zaidman-Rémy, A., M. Hervé, M. Poidevin, S. Pili-Floury, M.-S. Kim, D. Blanot, B.-H. Oh, R. Ueda, D. Mengin-Lecreulx, and B. Lemaitre. 2006. The Drosophila amidase PGRP-LB modulates the immune response to bacterial infection. Immunity 24:463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]