Abstract

Bacillus anthracis is surrounded by a polypeptide capsule composed of poly-gamma-d-glutamic acid (γDPGA). In a previous study, we reported that a monoclonal antibody (MAb F26G3) reactive with the capsular polypeptide is protective in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. The present study examined a library of six MAbs generated from mice immunized with γDPGA. Evaluation of MAb binding to the capsule by a capsular “quellung” type reaction showed a striking diversity in capsular effects. Most MAbs produced a rim type reaction that was characterized by a sharp increase followed directly by a decrease in refractive index at the capsular edge. Some MAbs produced a second capsular reaction well beneath the capsular edge, suggesting complexity in capsular architecture. Binding of MAbs to soluble γDPGA was assessed by a fluorescence perturbation assay in which a change in the MAb intrinsic fluorescence produced by ligand binding was used as a reporter for antigen-antibody interaction. The MAbs differed considerably in the complexity of the binding curves. MAbs producing rim type capsule reactions typically produced the more complex binding isotherms. Finally, the protective activity of the MAbs was compared in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. One MAb was markedly less protective than the remaining five MAbs. Characteristics of the more protective MAbs included a relatively high affinity, an immunoglobulin G3 isotype, and a complex binding isotherm in the fluorescence perturbation assay. Given the relatively monotonous structure of γDPGA, the results demonstrate a striking diversity in the antigen binding behavior of γDPGA antibodies.

Bacillus anthracis is surrounded by a polypeptide capsule composed of poly-gamma-d-glutamic acid (γDPGA). γDPGA is covalently linked to the peptidoglycan cell wall in a process that is mediated by CapD (3). The capsule biosynthetic operon capBCAD is found on the plasmid pXO2 (24, 38). Strains that lack pXO2 or have a specific deletion of capBCAD are highly attenuated in murine models of anthrax (7, 16, 41), indicating a key role for capsule formation in virulence. In a mouse model of pulmonary anthrax, encapsulation was shown to be essential for dissemination from the lungs and for persistence and survival of the bacterium in vivo (7). Given the key role of encapsulation in virulence, several recent studies have identified the capsule as a potential target for vaccine development (4, 17, 31, 34, 39). γDPGA is poorly immunogenic and behaves as a thymus-independent type 2 antigen (40). As a consequence, success in generation of an antibody response to γDPGA has been dependent on conjugation of either native γDPGA (4, 17, 31) or small glutamic acid polymers (34, 39) to immunogenic protein carriers.

Despite the potential importance of targeting γDPGA for antibody production, little is known regarding the immunochemistry of γDPGA-antibody interactions. The existing database is derived largely from a series of reports from Goodman and colleagues (11, 12, 18, 28, 32). These studies examined the interaction between polyclonal antibodies raised in rabbits and either native γDPGA or synthetic polypeptides. One of the findings of these early studies was indirect evidence that γDPGA may possess two distinct epitopes (12, 18).

We recently reported the use of a CD40 agonist monoclonal antibody (MAb) to substitute for T-cell help in generation of an antibody response to γDPGA in mice (19). This approach to immunization led to the production of several γDPGA MAbs. Passive immunization using one antibody, MAb F26G3, showed a high level of protection in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. This finding provided conceptual support for targeting γDPGA for vaccine development.

Active immunization with γDPGA may lead to production of antibodies against one or more epitopes on the polypeptide. Previous studies of MAbs directed against glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), the major capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans, found that capsular MAbs could be protective, nonprotective, or enhancing depending on the MAb epitope specificity, subclass, or dose (6, 25, 26, 33, 36). The goal of our study was to examine several immunochemical properties of a family of six γDPGA MAbs and to compare such immunochemical activities with the abilities of the antibodies to provide protection in a murine model of anthrax. The results showed considerable differences between the antibodies in their immunochemical activities and revealed a previously undescribed complexity in the architecture of the B. anthracis capsule. Most of the antibodies showed varying levels of protection, but there was one MAb that was poorly protective and exhibited immunochemical properties that were distinct from the protective antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. anthracis strains and isolation of γDPGA.

B. anthracis Pasteur is a strain maintained by the Nevada State Health Laboratory (Reno, NV). The strain was originally obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). B. anthracis Ames is a strain maintained at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and was originally obtained from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID, Frederick, MD). Bacillus licheniformis strain 9945 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Polyglutamic acid (PGA) was isolated from a culture of B. licheniformis that was grown for 60 h on a gyratory shaker (250 rpm) at 37°C on medium E that contained 2 mM MnCl2 · 4 H2O to stimulate maximal production of PGA in the D isoform (20, 37). PGA was isolated from the medium as described previously (19). Briefly, sodium acetate crystals and glacial acetic acid were added to final concentrations of 10% (wt/vol) and 1% (vol/vol), respectively, and the PGA was precipitated two times with 2 volumes of ethanol. Amino acid analysis showed the presence of only glutamic acid. A phenol-sulfuric acid test for carbohydrate (8) was negative. An acid hydrolysate showed a specific optical rotation of −25.2°, indicating that approximately 84% of the glutamic acid was the D isomer.

γDPGA was also isolated from a broth culture of B. anthracis Pasteur. A dialysate of brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) containing 0.8% NaHCO3 (125 ml) was inoculated with mucoid colonies selected from plates of nutrient agar (Difco) containing 0.8% NaHCO3. The broth culture was incubated for 72 h on a gyratory shaker (175 rpm) at 37°C in 15% CO2. Formaldehyde was added to a final concentration of 4% and incubated for 72 h at 37°C. Nonviability of the culture was confirmed by plating on 5% sheep blood agar (Difco). γDPGA was isolated from the broth as described above for PGA from B. licheniformis with the exception that precipitation was done with 1 volume of ethanol to limit the product to the high-molecular-weight fraction of γDPGA (19). Low-molecular-weight γDPGA was isolated by the addition of a second volume of ethanol to the supernatant fluid of culture medium containing 1 volume of ethanol. The γDPGA preparations isolated from B. anthracis Pasteur contained <2% protein and <0.5% nucleic acid. Polypeptides of 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, and 25 amino acids of γDPGA were synthesized by the Nevada Proteomics Center (University of Nevada, Reno) from 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl-d-glutamic acid (O-t-butyl) (Bachem, Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA) using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl chemistry. The peptides were purified to approximately 95% using a C8 YMC column on a Thermo Separations (San Jose, CA) P4000 preparative liquid chromatograph.

Formalin-killed B. anthracis Pasteur cells for evaluation of capsular “quellung” type reactions were obtained from the inactivated cultures prepared as described above for isolation of γDPGA. Cells of B. anthracis Ames were harvested from solid medium and killed with formalin before use. The cells were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the formalin and stored at 4°C as a sterile suspension. One experiment used bacteria that were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in an effort to remove capsular material. The DMSO treatment was done as described previously for treatment of C. neoformans yeast cells (10).

MAb production.

Most immunizations leading to production of MAbs were done with γDPGA that had been isolated from B. licheniformis. In one instance, γDPGA from B. anthracis Ames (USAMRIID collection) was used for immunization. In this case, the γDPGA was isolated from whole cells of B. anthracis and was purified as described previously (4). BALB/c mice were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 μg of γDPGA in combination with 400 μg of MAb FGK115, an agonist rat immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) anti-mouse CD40 (15). Mice were given an intravenous booster immunization with 0.5 or 1.0 μg γDPGA 25 days after the primary immunization, and spleens were collected 4 days later for production of hybridomas. Hybridomas were produced by fusion with the X63-Ag8.653 cell line using standard techniques. Production of γDPGA antibodies by hybridomas was evaluated by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in which γDPGA was used in the solid phase as described previously (19). Hybridoma cell lines were cloned by limiting dilution. MAb-secreting cell lines were grown in tissue culture in an Integra CL 1000 culture flask (Integra Biosciences, East Dundee, IL), and MAbs were isolated by affinity chromatography on protein A (Pierce, Rockford, IL). An irrelevant IgG3 MAb (MAb M600) reactive with the GXM of C. neoformans serotypes A and D was used as an isotype control. Fab fragments were produced from MAbs F24F2 and F26G3 by use of the Pierce ImmunoPure Fab kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's directions. Contaminating Fc fragments and intact IgG were removed by affinity chromatography on protein A (Pierce), and the Fab fragments were further purified by molecular sieve chromatography on Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Sequencing and analysis of variable regions.

First-strand cDNA was prepared from total mRNA isolated from murine hybridoma cells using reverse transcriptase primed with an Ig 3′ constant region degenerative primer (Mouse Ig-Primer set; Novagen, San Diego, CA). The cDNA was amplified by PCR using a series of Ig 5′ degenerative leader primers (Novagen). PCR products were ligated into the pGem-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI), cloned, and sequenced at the Nevada Genomics Center via the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method. At least two independent clones were sequenced for each chain. The nucleotide sequences of heavy and light chain variable regions were analyzed using searches of the IMGT/LIGM-DB comprehensive database of Ig and T-cell receptor nucleotide sequences with IMGT/V-QUEST and IMGT/JunctionAnalysis tools. Variable regions were assigned to gene families based on molecular subgroup designations compiled by IMGT (http://imgt.cines.fr).

Immunochemical assays.

Capsular “quellung” type reactions were evaluated by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope fitted with a Nikon confocal microscope C1 system and DIC optics. Precipitin formation by soluble γDPGA and the various MAbs was assessed by double immunodiffusion in agar (30).

The interactions between MAbs and γ-glutamyl peptides were quantified by monitoring the perturbation of tryptophan fluorescence that typically accompanies antibody binding. All titrations were performed on a Spex 111 spectrofluorometer using photon counting. Binding was measured by adding small aliquots of synthesized or native γDPGA dissolved in PBS to a solution of each MAb (25 μg/ml) in PBS. The fluorescence intensity was measured using 284-nm excitation and 341-nm emission wavelengths and right angle geometry. The γ-glutamyl peptides have no interfering fluorescence in this part of the spectrum; therefore, changes arise from antibody alone. Fluorescence data were corrected for excitation intensity. Five successive 10-s integration periods were averaged for each data point. The fluorescence yield was constant over this time period. The background fluorescence from a buffer blank was subtracted from all measurements, after which the fluorescence values of all solutions were corrected for dilution.

Plots of ΔF (fluorescence) versus γDPGA concentration were constructed. The apparent Kd in molar units was determined from the plots as the γDPGA concentration at one-half ΔFmax that was estimated by computer-aided fit to a hyperbolic binding isotherm (SigmaPlot; Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA).

To remove some of the ambiguities of single wavelength determinations, select interactions were monitored using fluorescence emission spectroscopy. Excitation was at 288 nm and emission was collected from 300 to 400 nm. This primarily measures changes in the tryptophan environment. Total fluorescence emission was estimated by integrating the spectrum. Spectral shifts were detected by Gaussian fits to the spectra or by difference spectra (subtracting the spectrum of MAb in the absence of antigen from the spectra of MAb in the presence of antigen).

Murine model of pulmonary anthrax.

Spores were prepared from B. anthracis Ames as described previously (19, 21). BALB/c mice were treated via the intraperitoneal route with γDPGA MAbs, an irrelevant control MAb (MAb M600) or PBS. Eighteen hours later, the mice were anesthetized with avertin, and a 50-μl inoculum containing approximately 104 spores (approximately 10 50% lethal doses) was inoculated into the lungs via the intratracheal route. Mice were observed twice daily to monitor survival or clinical symptoms. MAb treatment was given to 8 mice per group with the exception of the highest MAb dose (4,000 μg), where there were 5 mice per treatment group. Control groups (12 mice in experiment 1 and 16 mice in experiment 2) were given PBS instead of MAbs for each experiment. All treatment experiments were done two times under identical conditions, with the exception that mice were treated with 4,000 μg MAb for only the first experiment. Survival was evaluated by use of Kaplan-Meier curves. Dose-response curves were generated by plotting the log MAb concentration versus percent survival. Curves were evaluated by use of a sigmoidal dose-response equation, and results are reported as (i) the dose of MAb that produced 50% survival (ED50) and (ii) the slope of the curve at the ED50 (Hill slope). Confidence intervals for the ED50 and Hill slopes were calculated by the asymptotic method. Results of the replicate passive immunization experiments were combined for calculation of the ED50 and Hill slope. Survival curves and sigmoidal dose-response curves were evaluated with the assistance of Prism 4 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Six γDPGA MAbs were produced from 4 mice immunized with γDPGA in combination with the CD40 agonist MAb. The MAbs are identified in Table 1. Also shown in Table 1 are the molecular features of the MAbs based on analysis of variable region sequences.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of six MAbs produced by immunization with γDPGA in combination with CD40 agonist MAb

| MAb | Immunizing PGA | IgG subclass | VH IMGT subgroup | VH family | JH | D size (no. of residues) | VL IMGT subgroup | VL family | JL | No. of Trp residuesa | Accession no. forb:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy chain | Light chain | |||||||||||

| 21Bl | B. licheniformis | IgG1 | IGHV10S2*02 | Vh10 | 3 | 5 | IGKV1-135*01 | κ1 | 1 | 6 | EF030733 | EF030739 |

| F24F2 | B. licheniformis | IgG3 | IGHV10S2*02 | Vh10 | 2 | 7 | IGKV1-135*01 | κ1 | 4 | 5 | EF030730 | EF030736 |

| F24G7 | B. licheniformis | IgG3 | IGHV2S4*01 | VhQ52 | 3 | 7 | IGKV1-117*01 | κ1 | 1 | 6 | EF030734 | EF030740 |

| F26G3 | B. licheniformis | IgG3 | IGHV10S2*02 | Vh10 | 4 | 7 | IGKV1-135*01 | κ1 | 2 | 6 | EF030731 | EF030737 |

| F26G4 | B. licheniformis | IgG3 | IGHV5S18*01 | Vh7183 | 2 | 7 | IGKV1-135*01 | κ1 | 1 | 5 | EF030735 | EF030741 |

| F30D1 | B. anthracis | IgG3 | IGHV10S2*02 | Vh10 | 3 | 3 | IGKV6-15*01 | κ19/28 | 5 | 4 | EF030732 | EF030738 |

Number of tryptophan residues in MAb binding region.

Accession numbers are from the GenBank database.

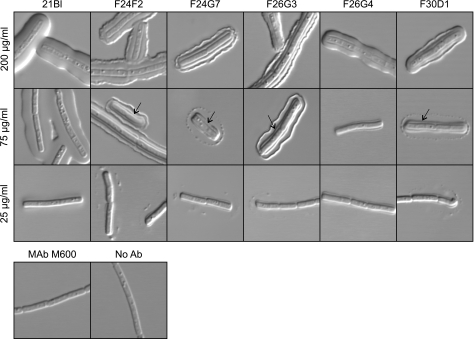

An initial experiment evaluated the capsular quellung type reaction that was produced by each MAb. Cells of formalin-killed B. anthracis (Ames strain) were incubated with each MAb at concentrations of 25, 75, or 200 μg/ml, and capsule reactions were assessed by DIC microscopy. The results (Fig. 1) showed that different MAbs produced strikingly different reactions. MAb 21Bl produced a capsule reaction that was very similar to the “puffy” reaction observed on binding of some MAbs with the capsule of C. neoformans (22). Four MAbs, F24F2, F24G7, F26G3, and F30D1, produced a dual-capsule reaction where there was a distinct reaction at a layer that was well beneath the capsule surface in the region of the cell wall and a second rim type reaction at the capsule perimeter. However, MAbs F24G7 and F30D1 differed from MAbs F24F2 and F26G3 in producing a punctate rim at 75 μg/ml. MAb F24F2 produced the dual reaction when used at a concentration of 75 μg/ml but produced a reaction that had features of both the rim and puffy patterns when used at a concentration of 200 μg/ml. The ability to produce a rim or puffy pattern was not a function of antibody concentration. Dilution of the puffy pattern MAb resulted in production of a more weakly staining pattern of the puffy type; dilution of rim pattern MAbs produced a punctate type of pattern at the capsule edge. Finally, MAb F26G4 produced a capsule reaction that was consistently smaller than was observed with the remaining MAbs and appeared only in the vicinity of the cell wall. The size of the F26G4 capsule reaction was dependent on the MAb concentration; a narrow reaction was found at 25 and 75 μg/ml, and the reaction was larger at 200 μg/ml.

FIG. 1.

Capsule reactions produced by binding of MAbs to B. anthracis Ames. Each MAb was incubated with B. anthracis at the indicated concentration, and the capsule reaction was assessed by DIC microscopy. Arrows identify an inner capsule reaction detected by MAbs F24F2, F24G7, F26G3, and F30D1. Bottom row: controls where B. anthracis was incubated with an irrelevant IgG3 MAb (MAb M600; 200 μg/ml) or no antibody (Ab).

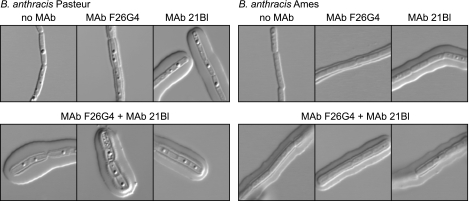

Results in Fig. 1 suggested that MAb F26G4 produced a capsule reaction only at the inner region of the capsule, whereas MAb 21Bl produced a capsule reaction that did not recognize the inner layer. To verify that this was indeed the case, bacilli were first incubated with MAb F26G4 to allow for binding to the inner layer and then incubated with MAb 21Bl to allow for formation of a capsule reaction with the outer layer. The experiment was done with bacilli of both the Ames and Pasteur strains to determine whether the two capsular layers were unique to the Ames strain. The results (Fig. 2) showed that incubation with either MAb alone produced the reaction expected on the basis of Fig. 1. Sequential addition of the antibodies produced a demonstrable capsule reaction with the inner layer and a puffy pattern in the outer layer with MAbs F26G4 and 21Bl. Similar results were obtained with both the Ames and Pasteur strains.

FIG. 2.

MAb F26G4 produces a capsule reaction only with an inner capsular layer, whereas MAb 21Bl produces a capsule reaction with only the outer capsular layer. Sequential addition of MAbs produces a reaction with both layers. Top row: left, DIC image in the absence of antibody; center, capsule reaction produced by MAb F26G4 alone (100 μg/ml); right, capsule reaction produced by MAb 21Bl alone (100 μg/ml). Bottom rows: images of three cells incubated with MAb F26G4 followed by MAb 21Bl (100 μg/ml each).

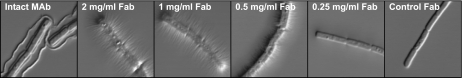

Our previous studies of MAbs reactive with the capsular polysaccharide of C. neoformans found that production of the rim pattern required a bivalent antibody. The ability to produce a rim was lost if the MAb was cleaved to a Fab. Cleavage of MAb F26G3 to Fab fragments similarly produced a loss in the ability of the MAb to produce the rim pattern (Fig. 3). The Fab retained the ability to produce a capsule reaction when viewed by DIC microscopy; however, the capsule reaction was less refractile and appeared as spindle-like extensions that radiated outward from the cell wall. A similar result was produced by Fab fragments of MAb F24F2 (not shown). Fab fragments of an irrelevant MAb that is reactive with the C. neoformans capsule produced no capsule reaction.

FIG. 3.

Capsule reaction produced by Fab of MAb F26G3. Left panel, intact MAb F26G3, 100 μg/ml; center panels, Fab fragments of MAb F26G3 at the indicated concentrations; right panel, irrelevant Fab of MAb 471, a MAb that is reactive with the capsular polysaccharide of C. neoformans, 1 mg/ml.

The polysaccharide capsule of C. neoformans consists of two distinct layers; an outer layer that is soluble in DMSO and an inner layer that is not removed by treatment with DMSO (10). Treatment of formalin-fixed B. anthracis cells in a similar manner with DMSO showed no apparent effect on the capsule or its interaction with any of the six capsular MAbs (data not shown).

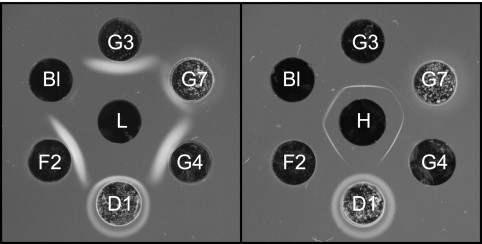

Our earlier studies of the interaction between MAb F26G3 and γDPGA by double immunodiffusion found that the MAb produced precipitin bands with high- and low-molecular-weight fractions of γDPGA (19). A similar evaluation of the six MAbs showed that MAbs F24F2, F26G3, and F26G4 produced strong precipitin bands with both the high- and low-molecular-weight fractions (Fig. 4). MAb 21Bl produced a strong band with the high-molecular-weight fraction and a barely discernible band with the low-molecular-weight fraction. MAb F24G7 produced bands of reduced intensity when compared with other MAbs. MAb F30D1 produced no precipitin bands. MAb F30D1 precipitated within and around the antibody well, suggesting autoaggregation; a lesser amount of precipitated antibody was also observed within and around the well containing MAb F24G7.

FIG. 4.

Double immunodiffusion showing precipitation of B. anthracis γDPGA by six MAbs. Left, low-molecular-weight fraction of γDPGA (L, center well); right, high-molecular-weight fraction of γDPGA (H, center well). Abbreviations: Bl, 21Bl; G3, F26G3; G7, F24G7; G4, F26G4; D1, F30D1; F2, F24F2.

Results shown in Fig. 1 and 2 suggested that the various MAbs were quite distinct in the manner of their interaction with the γDPGA capsule. One means to assess MAb interaction with capsular antigens is the fluorescence perturbation assay. In this assay, different antibodies display an intrinsic fluorescence that is dependent on the number of tryptophan residues and the environment for the residues. If there are tryptophan residues near the antigen-binding site, binding of antigen can cause a change in the intrinsic fluorescence and thus serve as a reporter for antigen binding by the MAb. This approach to measurement of the association of ligand and receptor has the advantage of simultaneously reporting changes at multiple sites on the MAb. We have used this assay to study the interaction of cryptococcal MAbs with capsular GXM (29).

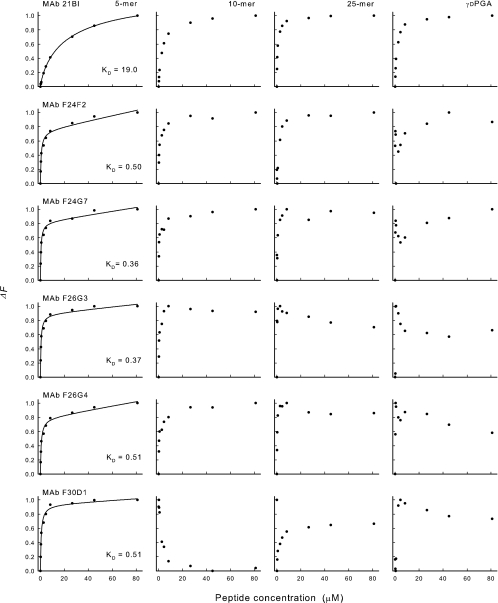

An experiment was done to assess the effect of antigen concentration on the intrinsic fluorescence of each MAb. In this experiment, synthetic polypeptides of 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, or 25 amino acids or native high-molecular-weight γDPGA from B. anthracis Pasteur were used over a concentration range of 0.18 to 80 μM. In the case of native γDPGA, the molar concentration was estimated assuming a repeating unit of 5 amino acids. Results are shown in Fig. 5 for the 5-mer, 10-mer, 25-mer, and native γDPGA. All MAbs showed a hyperbolic decrease in fluorescence (quenching) upon addition of increasing amounts of the 5-mer to each antibody. This hyperbolic relationship between ligand concentration and fluorescence suggests a simple, two-state binding to independent, noninteracting, binding sites. MAb 21Bl showed a similar hyperbolic curve with the 10-mer, 25-mer, and native γDPGA. A fit of the data from binding of the 5-mer peptide to a hyperbolic curve allowed for an estimation of the relative affinity of each antibody where the apparent Kd was calculated as the concentration of the peptide that produced half maximal quenching. The results are shown as Kd and are summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 5.

Changes in MAb fluorescence (excitation wavelength, 284 nm; emission wavelength, 341 nm) upon addition of increasing amounts of synthetic (5, 10, or 25 residues) or native γDPGA: ΔF = (F − Fo)/(Fsat − Fo), where Fo is the initial fluorescence intensity, Fsat is the fluorescence intensity at saturation, and F is the fluorescence intensity at the indicated isopeptide concentration.

TABLE 2.

Immunochemical and protective activities of γDPGA MAbs

| MAb | Result for:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsule reaction

|

Double immunodiffusion with γDPGAa

|

Fluorescence perturbation

|

Protective activity

|

|||||||

| Outer layer (concn [μg/ml])

|

Inner layer (75 μg/ml) | High mol wt | Low mol wt | Kd (μM) | Maximum ΔF (%) | ED50 (μg) (95% CIc) | Hill slope (95% CI) | |||

| 200 | 75 | 25 | ||||||||

| 21Bl | Puffy | Puffy | Negative | None | Strong | Trace | 19 | 24 | 3,500 (1,100-11,000) | 1.1 (−0.01-2.1) |

| F24F2 | Mixed | Rim | Punctate | Yes | Strong | Strong | 0.50 | 39 | 480 (250-660) | 1.3 (0.8-1.8) |

| F24G7 | Rim | Punctate | Punctate | Yes | Reduced | Reduced | 0.36 | 13 | 1,100 (840-1,500) | 1.8 (0.9-2.6) |

| F26G3 | Rim | Rim | Punctate | Yes | Strong | Strong | 0.37 | 23 | 590 (490-700) | 2.1 (1.4-2.8) |

| F26G4 | None | None | None | Yes | Strong | Strong | 0.51 | 32 | 460 (280-760) | 1.7 (0.4-3.0) |

| F30D1 | Rim | Punctate | Punctate | Yes | No pptb | No ppt | 0.51 | 26 | 1,200 (650-2,300) | 0.9 (0.4-1.5) |

Immunodiffusion was done with γDPGA from B. anthracis.

The absence of a precipitate (ppt) with MAb F30D1 is most likely due to an artifact, i.e., autoaggregation.

CI, confidence interval.

In contrast to results obtained by use of the 5- and 10-mer polypeptides, the addition of native γDPGA to MAbs F24F2, F24G7, F26G3, and F26G4 produced a biphasic curve where there was an initial increase in quenching upon addition of small amounts of peptide; however, with intermediate amounts of γDPGA, the level of quenching decreased from maximal levels and sometimes showed a gradual increase in quenching as large amounts of γDPGA were added (Fig. 5). This biphasic curve was also observed with the 25-mer in the case of MAb F26G3. Finally, MAb F30D1 produced different titration patterns with the 10-mer, the 25-mer and native γDPGA. In the case of the 10-mer, a hyperbolic enhancement of fluorescence was observed. A biphasic curve was observed upon addition of the 25-mer to MAb F30D1, in which there was an enhancement of fluorescence upon addition of the lowest amount of peptide that was followed by quenching from such maximal levels upon addition of increasing amounts of polypeptide. A triphasic curve was found upon addition of increasing amounts of native γDPGA to MAb F30D1, where there was an initial enhancement of fluorescence followed by quenching and eventual enhancement.

To analyze the data further, the fluorescence was plotted as 1/ΔF versus 1/[L] and as ΔF versus ΔF/[L]. These linear equations revealed that in all cases presented in Fig. 5, binding consisted of a high-affinity phase and a low-affinity phase—even in the cases of apparent hyperbolic binding (data not shown).

One binding isotherm was examined in more detail. Binding of the 3-mer by MAb F26G3 was followed by emission spectroscopy (300 to 400 nm, excitation at 288 nm). The 3-mer was chosen for the more detailed study because it is the smallest of the ligands reported here. This has at least four advantages: the 3-mer (i) has the smallest potential conformational repertoire, (ii) is likely to have the lowest energy barrier between conformers, (iii) is the most likely to behave as a univalent antigen, and (iv) has the greatest difference in the standard state free energy of binding (see Fig. 7 below). These factors suggest that the 3-mer binding isotherm will be the least complicated and most likely to reveal differences between antibodies. The change in total oscillator strength was approximated by Gaussian fits to the emission spectrum and by integration of the emission spectrum. In both cases, area decreased hyperbolically with antigen concentration (data not shown). Therefore, the changes observed in the single wavelength data (Fig. 5) represent a decrease in quantum efficiency. At the antibody concentration used, the affinity of the interaction kept both ligand and receptor concentrations limiting for much of the titration. For example, half saturation of the antibody occurred at a molar ratio of 1 bound 3-mer to 1 free 3-mer. The spectra also revealed a complicated shift of λmax in emission intensity. A blue shift commenced as antibody exceeded half saturation. This was followed by a red shift that commenced at saturation, as judged by total fluorescence intensity (data not shown). Therefore, binding at the second of the two MAb binding sites induces interactions between remote parts of the antibody. The spectral changes provide support for complicated changes in single-wavelength titrations and the broken double-reciprocal plots (see above paragraph).

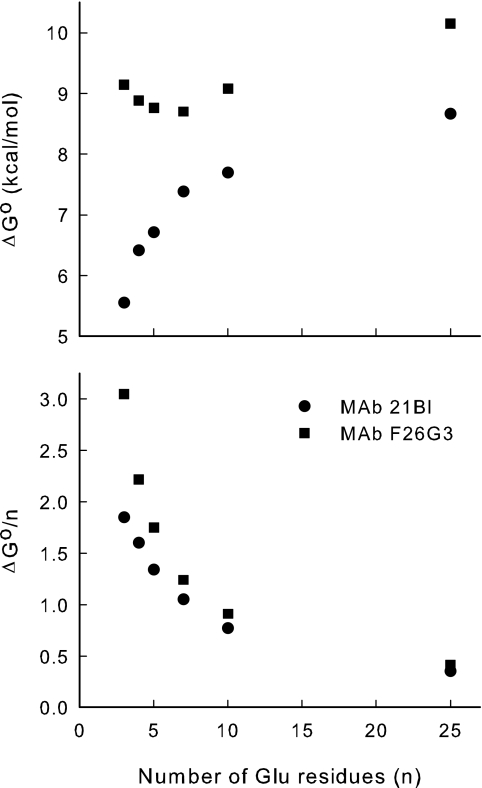

FIG. 7.

Apparent free energy of binding as a function of γDPGA peptide size. The free energy of binding was obtained from the apparent Kd of the high-affinity phase of the binding isotherms (Fig. 5).

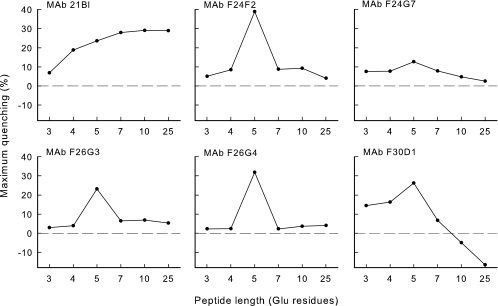

Analysis of the titration curves for the entire range of synthetic polypeptides (3-mer to 25-mer) showed that the MAbs differed considerably in the extent of maximal perturbation and in the effect of polypeptide size on the extent of quenching (Fig. 6). Maximal quenching was observed with a pentapeptide with all MAbs except MAb 21Bl; reduced quenching was observed with peptides that were larger or smaller than 5 amino acids. In contrast, MAb 21Bl produced a gradual increase in quenching with increased peptide size up to 10 amino acids. Finally, MAb F30D1 showed enhanced fluorescence with peptides of 10 or 25 amino acids.

FIG. 6.

Effect of polypeptide length on the maximal level of fluorescence perturbation. Increasing amounts of each polypeptide were added to each MAb as shown in Fig. 5. Each titration curve was then inspected to determine the maximal level of quenching. Results are reported as the maximum quenching observed for each titration as a function of polypeptide length.

Data shown in Fig. 5 were further analyzed for MAbs 21Bl and F26G3. In this analysis, the binding energies for synthetic peptides of increasing degrees of polymerization were calculated from the apparent dissociation constant of the high-affinity component of the binding isotherm. Our expectation was that the binding energy would increase with increased antigen size as the antigen occupies more of the binding site. However, as the size of the antigen increases beyond the size of the binding site, the binding energy would become insensitive to antigen size. This is illustrated in Fig. 7 (upper panel). Note, in particular, the remarkable qualitative differences between the two antibodies in the effect of the degree of polymerization on the apparent binding energy. However, in both cases, a polymer of approximately 10 residues appears to fill the antibody-binding site.

Normalizing the binding energy to the antigen size provides some information regarding the topography of the MAb binding sites (Fig. 7, lower panel). In a simple example, one might expect binding per degree of polymerization to be constant until the antigen size exceeded the size of the binding site; at this point, energy per residue would decrease. However, for both MAbs 21Bl and F26G3, binding energy per residue decreased (lower panel) while the total binding energy is increased (upper panel, MAb 21Bl). This indicates a variety of subsites on the antibody. The highest-affinity subsite can accommodate only a small number of residues. Although additional residues interact with MAb, they are relegated to subsites with suboptimal complementarity.

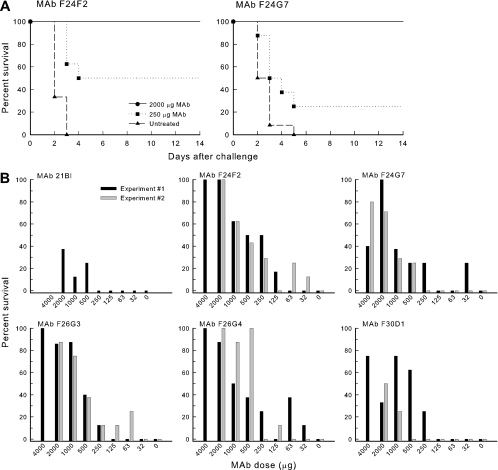

A final experiment compared the abilities of the six MAbs to protect mice in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. Representative Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mice that were untreated (PBS) or treated via the intraperitoneal route with 250 or 2,000 μg of MAb F24F2 or F24G7 are illustrated in Fig. 8A. Mice that were untreated followed a rapidly lethal course with death typically occurring after 3 days. Mice treated with 2,000 μg of either MAb showed 100% survival. Mice treated with 250 μg MAb followed an intermediate curve in which death was slightly delayed for some mice, and several mice survived the challenge.

FIG. 8.

Passive immunization in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. Mice were treated via the intraperitoneal route with the indicated amount of MAb or PBS 18 h prior to intratracheal challenge with 104 B. anthracis Ames spores. (A) Representative Kaplan-Meier plot showing course of survival in sham-treated mice or mice treated with 2,000 or 250 μg MAb F24F2 or F24G7 18 h prior to intratracheal challenge. (B) Dose-response curve showing percent survival for mice treated with various amounts of each MAb. Results are shown for two separate experiments for all MAbs, except 21Bl, which was only done for a single experiment. Protection following treatment with 4,000 μg MAb was only done for experiment 1, with the exception of MAb F24G7, which was used at the 4,000-μg dose for both experiments.

A detailed dose-response evaluation of protection afforded by each MAb is shown in Fig. 8B, where the data are plotted as percent survival versus MAb dose. Results are shown for two independent experiments. Results of the two experiments were combined to calculate an ED50 for each MAb as well as the Hill slope for each titration curve. The results of these calculations are reported in Table 2. The three MAbs showing the highest levels of protection were F24F2, F26G3, and F26G4. MAb 21Bl provided little protection; MAbs F24G7 and F30D1 were intermediate in protection. The Hill slopes for the titrations did not differ appreciably from one another. Finally, a similar titration (8 mice per group) was done with an irrelevant IgG3 MAb that is reactive with the C. neoformans capsular polysaccharide (MAb M600). No protection was observed at any dose (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Antibodies to capsular polysaccharides of a broad spectrum of bacteria and the encapsulated yeast C. neoformans are protective. B. anthracis is unique among the encapsulated pathogens because the capsule is composed of a polyisopeptide rather than a polysaccharide. Interactions between antibodies and capsular polysaccharides have received extensive study. The primary objective of our study was to evaluate several immunochemical parameters of the interactions between antibodies and the capsular polypeptide of B. anthracis. Capsular polysaccharides and the polypeptide capsule of B. anthracis are T-independent antigens. Our study took advantage of a library of six γDPGA MAbs that was generated in response to immunization with γDPGA from B. licheniformis (19) or B. anthracis (this study) in combination with a CD40 agonist antibody as a means for bypassing the need for T-cell support.

The ability of antibody to render a microbial capsule visible by light microscopy has been known since Neufeld's studies of the pneumococcal capsule (27). The ability of antibody to the B. anthracis polypeptide capsule to produce a similar capsule reaction was reported by Bodon and Tomcsik (2). We recently reported that MAbs reactive with the capsular polysaccharide of C. neoformans can produce two distinct capsule reactions when viewed by DIC microscopy, depending on the epitope specificity of the antibody or the serotype of the capsular polysaccharide (23). One capsule reaction, termed “puffy,” is characterized by an initial increase in the refractive index at the capsular edge, followed by a gradient of change throughout the capsule. The second reaction, termed “rim,” is characterized by an abrupt increase, followed directly by a rapid decrease in the refractive index at the capsular edge. The ability to produce a rim pattern is dependent on cross-linking of the capsular matrix by antibody. Notably, rim pattern antibodies are protective in a murine model of cryptococcosis, and puffy pattern antibodies are not protective (22).

Examination of capsule reactions produced by γDPGA MAbs showed a remarkable degree of diversity. MAb 21Bl produced a puffy type reaction similar to that observed with nonprotective C. neoformans MAbs. MAb 21Bl was very poorly protective. Four of the remaining γDPGA MAbs produced variations of the rim pattern. Although there were varying degrees of protection afforded by these MAbs, the levels of protection were markedly higher than protection observed with 21Bl. It would be premature to ascribe a causal association between production of the puffy pattern and a failure to protect because MAb 21Bl is an IgG1 antibody, whereas the remaining MAbs are IgG3 antibodies. As a consequence, the failure of 21Bl to protect could be due to its subclass rather than molecular characteristics of MAb-capsule interactions leading to the puffy reaction. Nevertheless, the parallels with results from studies of cryptococcal MAbs are striking. As was the case with rim pattern C. neoformans MAbs, the ability of γDPGA MAbs to produce a rim-type reaction required an intact, bivalent MAb (Fig. 3), suggesting that the rim pattern is a consequence of cross-linking of the capsular edge by the MAb.

Capsule reactions produced by some MAbs revealed a previously undescribed level of complexity in capsule architecture. Some MAbs not only produced a rim pattern at the capsule perimeter but also produced a distinct capsule reaction in a zone that was close to the cell wall. MAb 21Bl did not stain this inner zone. MAb F26G4 appeared to produce only the inner capsule reaction and did not produce the outer rim pattern characteristic of most MAbs. The fact that MAbs 21Bl and F26G4 displayed differential interactions with the capsule was confirmed by sequential addition of the antibodies to produce capsule reactions that showed both the puffy reaction characteristic of MAb 21Bl and the inner capsule reaction characteristic of F26G4. Notably, MAb F26G4 was one of the most protective of the antibodies, suggesting that the ability to produce the outer rim reaction is not a requirement for protection. Alternatively, it is possible that MAb F26G4 produces a different reaction with B. anthracis in vivo than what is observed with cells grown in culture. In studies of capsule reactions produced by MAbs reactive with the C. neoformans capsule, we have found some antibodies that produce different capsule reactions with yeast cells grown in vitro versus cells harvested from infected tissue (unpublished observations).

The structural basis for the inner capsule architecture is not known. Previous studies of the cryptococcal capsule found that the capsule consisted of an outer layer that is DMSO soluble and an inner layer that is DMSO resistant (10). This was not the case with B. anthracis because treatment of encapsulated B. anthracis with DMSO had no apparent effect on either capsule size or the ability of MAbs to produce capsule reactions. The B. anthracis cell wall is surrounded by two abundant surface proteins, extractable antigen 1 and surface array protein, that comprise the B. anthracis S-layer (9). The capsule overlies the S-layer. It is unlikely that γDPGA MAbs are reactive with these proteins, but it is possible that the inner capsule reaction represents an interaction between the γDPGA capsule and the S-layer.

The complexity of the pattern of fluorescence perturbation upon addition of increasing amounts of native γDPGA to each MAb was an additional feature that distinguished the poorly protective 21Bl from the remaining antibodies. A hyperbolic loss of fluorescence was observed in the case of MAb 21Bl. The remaining MAbs produced a biphasic or triphasic curve that was characterized by an initial loss of fluorescence, followed by a return of fluorescence on addition of further γDPGA. Initial analysis indicates that this complex pattern is the result of a combination of loss of quantum yield and a combination of blue and red shifts in the emission spectra. Our previous studies of the interactions of capsular MAbs with C. neoformans found that the rim pattern is associated with cross-linking of the capsule, whereas production of the puffy pattern did not require cross-linking. One interpretation of the fluorescence perturbation assay results is the possibility that the hyperbolic response is a signature of puffy-pattern MAbs, whereas the biphasic response is characteristic of MAbs that produce the rim pattern. In support of this argument, we have found cryptococcal MAbs that produce a rim pattern also exhibit a biphasic fluorescence perturbation titration, whereas Fab fragments of the same antibodies produce a hyperbolic titration (unpublished results).

Fluorescence titrations of γ-glutamyl isopeptides with multiple MAbs revealed diverse, complex interactions. Ligand binding leads to a loss of quantum efficiency, most likely due to a close interaction between the antigen and a tryptophan residue. This interaction is the result of high-affinity binding; at the antibody concentrations used in this study, the reaction was stoichiometric, with half saturation of the antibody occurring at a ratio of 1 bound antigen to 1 free antigen. However, shifts in the spectrum were observed at concentrations of the 3-mer beyond that required to saturate the MAb (as judged by quenching). This suggests secondary trimer binding sites and is consistent with the effect of antigen on the fluorescence titrations (see below).

Maximal fluorescence quenching was a function of hapten size, with maximum quenching obtained with the pentamer. This finding indicates a point of similarity between the antibody binding sites of the different MAbs. Apparently, the pentamer is of the right size to maximize the interaction between one or more tryptophans at the binding site. Measurement of binding energy as a function of antigen size indicates that the antibody binding site accommodates 10 glutamyl residues in the antigen conformation bound to antibody (Fig. 7). The complex changes in intensity in single wavelength titrations of larger antigens most likely are the result of antigen-induced conformational changes in the antibody structure. The mechanism of these changes is currently being investigated.

An evaluation of the free energy of binding showed an additional level of diversity in ligand binding by γDPGA MAbs. The γ-glutamyl oligomers are floppy antigens capable of adopting multiple conformations both free in solution and in complexes with proteins. There is no a priori reason why antibodies will bind antigens in the same orientation nor why antigens should bind in the same conformation. These physicochemical differences ultimately account for the biological differences between antibodies. Such differences are illustrated in a comparison of the free energies of binding of the γ-glutamyl antigens by MAbs 21Bl and F26G3. Figure 7 demonstrates a remarkable relationship between oligomer size and antibody affinity. The two antibodies bind the 3-mer much differently (approximately a 4-kcal/mol difference). However, the free energy of binding to MAb 21Bl increases dramatically as oligomer size increases, whereas oligomer size has little effect on MAb F26G3. In other words, MAb 21Bl strongly discriminates between oligomers, whereas MAb F26G3 has comparatively little selectivity.

How much does each residue of the oligomer contribute to the difference in the selectivity of the two antibodies? The lower panel of Fig. 7 addresses this question by dividing the apparent free energy of binding by the number of residues in the oligomer. In the 3-mer, each residue contributes about 3 kcal/mol to MAb F26G3 binding and 2 kcal/mol to MAb 21Bl binding, indicating that MAb F26G3 is more complementary to the 3-mer than MAb 21Bl. However, this difference is quite sensitive to oligomer size. For example, the difference in binding of the 10-mer is only a few 10ths of a kilocalorie per mole per residue. In the larger antigens, on average, each residue contributes about equally to binding of the two antibodies.

MAbs F24G7 and F30D1 were significantly (P < 0.05) less protective than MAbs F24F2, F26G3, and F26G4, despite the fact that the affinities of the five MAbs for the 5-mer peptide were quite similar. The explanation may lie in the immunodiffusion patterns produced by the various antibodies. Murine IgG3 antibodies have a tendency to self aggregate (1, 5, 14). As is evident from the immunodiffusion results, MAb F30D1 produced a pronounced zone of precipitate around the antibody well such that no precipitation occurred with γDPGA. MAb F24G7 produced a lesser zone of precipitation around the antibody well, but there was an appreciable diminution in the precipitin band with γDPGA relative to the other MAbs. This tendency to self aggregate may have reduced the functional concentration of these two MAbs.

Despite differences in ED50, the dose-response curves for the five protective MAbs displayed similar slopes (Hill slope). Finally, prozone-like effects have been described for passive immunization experiments in which antibody-mediated protection is lost at high doses of antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae (13) and C. neoformans (35, 36). We did not observe prozone-like effects in the case of B. anthracis. We cannot exclude the possibility that a prozone might be observed with antibodies of other IgG subclasses, with different challenge inocula, or with a different challenge route.

In summary, our results indicate that MAbs reactive with γDPGA display a diverse array of immunochemical interactions with soluble and capsular γDPGA. Properties that are associated with the highest levels of protection in a murine model of anthrax include high intrinsic affinity, production of a rim-type capsule reaction, production of a biphasic fluorescence perturbation titration curve, and an absence of self aggregation. On the basis of these results, we have identified MAbs F24F2 and F26G3 as candidates for further evaluation for passive immunization in treatment of pulmonary anthrax.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI059348 and AI061200.

We thank Arthur Friedlander (USAMRIID, Frederick, MD) for providing the B. anthracis Ames γDPGA that was used to produce MAb F30D1. Megan Whitaker provided technical assistance for spectrofluorometric analysis.

Editor: A. Casadevall

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelmoula, M., F. Spertini, T. Shibata, Y. Gyotoku, S. Luzuy, P. Lambert, and S. Izui. 1989. IgG3 is the major source of cryoglobulins in mice. J. Immunol. 143:526-532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodon, G., and J. Tomcsik. 1934. Effect of antibody on the capsule of anthrax bacilli. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 32:122. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candela, T., and A. Fouet. 2005. Bacillus anthracis CapD, belonging to the γ-glutamyltranspeptidase family, is required for the covalent anchoring of capsule to peptidoglycan. Mol. Microbiol. 57:717-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chabot, D. J., A. Scorpio, S. A. Tobery, S. F. Little, S. L. Norris, and A. M. Friedlander. 2004. Anthrax capsule vaccine protects against experimental infection. Vaccine 23:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper, L. J. N., J. C. Schimenti, D. D. Glass, and N. S. Greenspan. 1991. H chain C domains influence the strength of binding of IgG for streptococcal group A carbohydrate. J. Immunol. 146:2659-2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dromer, F., J. Charreire, A. Contrepois, C. Carbon, and P. Yeni. 1987. Protection of mice against experimental cryptococcosis by anti-Cryptococcus neoformans monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 55:749-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drysdale, M., S. Heninger, J. Hutt, Y. Chen, C. R. Lyons, and T. M. Koehler. 2005. Capsule synthesis by Bacillus anthracis is required for dissemination in murine inhalation anthrax. EMBO J. 24:221-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubois, M., K. A. Gilles, J. K. Hamilton, P. A. Rebers, and F. Smith. 1956. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28:350-356. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouet, A., S. Mesnage, E. Tosi-Couture, P. Gounon, and M. Mock. 1999. Bacillus anthracis surface: capsule and S-layer. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gates, M. A., P. Thorkildson, and T. R. Kozel. 2004. Molecular architecture of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule. Mol. Microbiol. 52:13-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman, J. W., and D. E. Nitecki. 1966. Immunochemical studies on the poly-γ-D-glutamyl capsule of Bacillus anthracis. I. Characterization of the polypeptide and of the specificity of its reaction with rabbit antisera. Biochemistry 5:657-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman, J. W., D. E. Nitecki, and I. M. Stoltenberg. 1968. Immunochemical studies on the poly-γ-D-glutamyl capsule of Bacillus anthracis. III. The activity with rabbit antisera of peptides derived from the homologous polypeptide. Biochemistry 7:706-710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodner, K. and F. L. Horsfall, Jr. 1935. The protective action of type I antipneumococcus serum in mice. I. Quantitative aspects of the mouse protection test. J. Exp. Med. 62:359-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grey, H. M., J. W. Hirst, and M. Cohn. 1971. A new mouse immunoglobulin: IgG3. J. Exp. Med. 133:289-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hixon, J. A., B. R. Blazar, M. R. Anver, R. H. Wiltrout, and W. J. Murphy. 2001. Antibodies to CD40 induce a lethal cytokine cascade after syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 7:136-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivins, B. E., J. W. Ezzell, Jr., J. Jemski, K. W. Hedlund, J. D. Ristroph, and S. H. Leppla. 1986. Immunization studies with attenuated strains of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 52:454-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyce, J., J. Cook, D. J. Chabot, R. Hepler, W. Shoop, Q. Xu, T. Stambaugh, M. Aste-Amezaga, S. Wang, L. Indrawati, M. Bruner, A. Friedlander, P. Keller, and M. Caufield. 2006. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Bacillus anthracis poly-γ-D-glutamic acid capsule covalently coupled to a protein carrier using a novel triazine-based conjugation strategy. J. Biol. Chem. 281:4831-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs, J., A. Kapoor, U. R. Ghatak, G. L. Mayers, V. R. Giannasio, R. Giannotti, G. Senyk, D. E. Nitecki, and J. W. Goodman. 1972. Synthesis of poly-gamma-glutamyl-gamma-aminobutyric acids and their reactivity with antiserum against Bacillus anthracis polypeptide. Biochemistry 11:1953-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel, T. R., W. J. Murphy, S. Brandt, B. R. Blazar, J. A. Lovchik, P. Thorkildson, A. Percival, and C. R. Lyons. 2004. mAbs to Bacillus anthracis capsular antigen for immunoprotection in anthrax and detection of antigenemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:5042-5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard, C. G., R. D. Housewright, and C. B. Thorne. 1958. Effects of some metallic ions on glutamyl polypeptide synthesis by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 76:499-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons, C. R., J. Lovchik, J. Hutt, M. F. Lipscomb, E. Wang, S. Heninger, L. Berliba, and K. Garrison. 2004. Murine model of pulmonary anthrax: kinetics of dissemination, histopathology and mouse strain susceptibility. Infect. Immun. 72:4801-4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacGill, T. C., R. S. MacGill, A. Casadevall, and T. R. Kozel. 2000. Biological correlates of capsular (quellung) reactions of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Immunol. 164:4835-4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacGill, T. C., R. S. MacGill, and T. R. Kozel. 2001. Capsular reaction of Cryptococcus neoformans with polyspecific and oligospecific polyclonal anticapsular antibodies. Infect. Immun. 69:1189-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makino, S., I. Uchida, N. Terakado, C. Sasakawa, and M. Yoshikawa. 1989. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region, which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 171:722-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukherjee, J., G. Nussbaum, M. D. Scharff, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Protective and non-protective monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans originating from one B-cell. J. Exp. Med. 181:405-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee, J., M. D. Scharff, and A. Casadevall. 1992. Protective murine monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 60:4534-4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neufeld, F. 1902. Ueber die agglutination der pneumokokken und über die theorieen der agglutination. Z. Hyg. Infektionskrankh. 40:54-72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitecki, D. E., and J. W. Goodman. 1966. Immunochemical studies on the poly-γ-D-glutamyl capsule of Bacillus anthracis. II. The synthesis of eight dipeptides and four tripeptides of glutamic acid. Biochemistry 5:665-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otteson, E. W., W. H. Welch, and T. R. Kozel. 1994. Protein-polysaccharide interactions: a monoclonal antibody specific for the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Biol. Chem. 269:1858-1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouchterlony, Ö. 1948. In vitro method for testing the toxin-producing capacity of diphtheria bacteria. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 25:186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhie, G. E., M. H. Roehrl, M. Mourez, R. J. Collier, J. J. Mekalanos, and J. Y. Wang. 2003. A dually active anthrax vaccine that confers protection against both bacilli and toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10925-10930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roelants, G. E., L. F. Whitten, A. Hobson, and J. W. Goodman. 1969. Immunochemical studies on the poly-γ-D-glutamyl capsule of Bacillus anthracis. VI. The in vivo fate and distribution to immunized rabbits of the polypeptide in immunogenic and nonimmunogenic forms. J. Immunol. 103:937-943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanford, J. E., D. M. Lupan, A. M. Schlageter, and T. R. Kozel. 1990. Passive immunization against Cryptococcus neoformans with an isotype-switch family of monoclonal antibodies reactive with cryptococcal polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 58:1919-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneerson, R., J. Kubler-Kielb, T. Y. Liu, Z. Dai, S. H. Leppla, A. Yergey, P. Backlund, J. Shiloach, F. Majadly, and J. B. Robbins. 2003. Poly(γ-D-glutamic acid) protein conjugates induce IgG antibodies in mice to the capsule of Bacillus anthracis: a potential addition to the anthrax vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8945-8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taborda, C. P., and A. Casadevall. 2001. Immunoglobulin M efficacy against Cryptococcus neoformans: mechanism, dose dependence, and prozone-like effects in passive protection experiments. J. Immunol. 166:2100-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taborda, C. P., J. Rivera, O. Zaragoza, and A. Casadevall. 2003. More is not necessarily better: prozone-like effects in passive immunization with IgG. J. Immunol. 170:3621-3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorne, C. B., and C. G. Leonard. 1958. Isolation of D- and L-glutamyl polypeptides from culture filtrates of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 233:1109-1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida, I., S. Makino, C. Sasakawa, M. Yoshikawa, C. Sugimoto, and N. Terakado. 1993. Identification of a novel gene, dep, associated with depolymerization of the capsular polymer in Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Microbiol. 9:487-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, T. T., P. F. Fellows, T. J. Leighton, and A. H. Lucas. 2004. Induction of opsonic antibodies to the gamma-D-glutamic acid capsule of Bacillus anthracis by immunization with a synthetic peptide-carrier protein conjugate. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, T. T., and A. H. Lucas. 2004. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis behaves as a thymus-independent type 2 antigen. Infect. Immun. 72:5460-5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welkos, S. L. 1991. Plasmid-associated virulence factors of non-toxigenic (pX01-) Bacillus anthracis. Microb. Pathog. 10:183-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]