Abstract

While Cryptosporidium parvum infection of the intestine has been reported in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, biliary infection is seen primarily in adult AIDS patients and is associated with development of AIDS cholangiopathy. However, the mechanisms of pathogen-induced AIDS cholangiopathy remain unclear. Since we previously demonstrated that the Fas/Fas ligand (FasL) system is involved in paracrine-mediated C. parvum cytopathicity in cholangiocytes, we also tested the potential synergistic effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transactivator of transcription (Tat)-mediated FasL regulation on C. parvum-induced apoptosis in cholangiocytes by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR, immunoblotting, immunofluorescence analysis, and immunogold electron microscopy. H69 cells do not express CXCR4 and CCR5, which are receptors required for direct HIV-1 viral infection. However, recombinant biologically active HIV-1-associated Tat protein increased FasL expression in the cytoplasm of cholangiocytes without a significant increase in apoptosis. We found that C. parvum-induced apoptosis was associated with translocation of intracellular FasL to the cell membrane surface and release of full-length FasL from infected H69 cells. Tat significantly (P < 0.05) increased C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander cells in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, Tat enhanced both C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation and release of full-length FasL. In addition, the FasL neutralizing antibody NOK-1 and the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-fmk both blocked C. parvum-induced apoptosis in cholangiocytes. The data demonstrated that HIV-1 Tat enhances C. parvum-induced cholangiocyte apoptosis via a paracrine-mediated, FasL-dependent mechanism. Our results suggest that concurrent active HIV replication, with associated production of Tat protein, and C. parvum infection synergistically increase cholangiocyte apoptosis and thus jointly contribute to AIDS-related cholangiopathies.

Cryptosporidium parvum is an enteric pathogen and a common cause of diarrhea in humans and animals worldwide. In immunocompetent individuals, infection is usually limited to the intestine and causes an acute, self-limited disease. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, cryptosporidiosis may cause potentially fatal complications, including bile duct damage (12, 17, 21, 25, 30). AIDS cholangiopathy, a group of biliary disorders including secondary sclerosing cholangitis and acalculous cholecystistis seen in AIDS patients, causes significant morbidity and mortality (35, 50). Recent studies have indicated that development of this biliary syndrome involves opportunistic infection of the biliary tree. While a number of pathogens have been implicated, C. parvum is the single most common identifiable pathogen associated with this disease. Although biliary cryptosporidiosis is also seen in boys with X-linked immunodeficiency (18, 22), in adults it has been reported only in patients with AIDS (12, 17, 21, 25, 30). In contrast, C. parvum infection of the intestine has been found in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised subjects (40). Thus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and C. parvum may have unique synergistic pathological effects on the biliary tree.

It has been established that HIV-1 infects hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and endothelial cells in the liver (8, 23); cholangiocyte infection has never been documented. During active replication, HIV-1 can also affect uninfected cells via release of HIV-derived soluble peptides from directly infected cells (27, 45, 46). One of these peptides, the HIV-encoded transactivator of transcription (Tat), circulates in the blood and is taken up by most cell types, including epithelial cells (44). Tat is essential for replication of the viral genome, and it has been proposed that Tat is an important factor in HIV-induced pathogenesis of AIDS (2). Exogenous Tat has a variety of effects on cellular processes in uninfected cells, including increased binding of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) to DNA, increased production of cytokines, increased expression of cytokine receptors, and modulation of cell survival and proliferation (2, 19, 31, 34, 42). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that Tat increases apoptosis in a variety of cell types, including cell types not directly infected by HIV-1 (4, 42). Indeed, Tat synergizes with T-cell-activating stimuli in the upregulation of Fas ligand (FasL), a molecule that activates the Fas death receptor, resulting in apoptotic cell death (4, 48, 49).

Although the clinical features of biliary cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients are well documented, it is not clear why individuals infected with HIV are susceptible to biliary cryptosporidiosis and associated cholangiopathies, in contrast to individuals immunocompromised by other mechanisms. We previously demonstrated that C. parvum is cytopathic to bystander uninfected cholangiocytes through a paracrine Fas/FasL-dependent apoptotic mechanism (9). It appears that C. parvum possesses a complex virulence capacity to initiate several signaling cascades within the infected host cell that may contribute to the development of disease, including activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, resulting in apoptotic resistance in directly infected cells (14). Interestingly, C. parvum infection also upregulates FasL expression in infected cells and causes apoptosis in bystander noninfected cells via activation of the Fas/FasL death pathway (9). Highly active antiretroviral therapy has decreased the incidence of AIDS cholangiopathies and has dramatically improved the survival rates of individuals with AIDS cholangiopathies (29). However, C. parvum biliary infection and AIDS cholangiopathy remain significant problems in individuals that do not respond or do not have access to this therapy. How C. parvum activates the Fas/FasL death pathway and whether soluble factors released during active HIV-1 replication potentiate C. parvum-induced cholangiocyte death are unclear.

In the work described here, we found that apoptotic cell death in bystander cholangiocytes induced by C. parvum is associated with FasL membrane translocation and release of full-length FasL in infected cells. HIV-1 Tat protein increases FasL protein expression in the cytoplasm of cultured cholangiocytes without an increase in apoptosis. Moreover, Tat enhances C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation, release of full-length FasL in infected cells, and, consequently, apoptotic cell death in uninfected bystander cells. Therefore, Tat sensitizes cultured cholangiocytes to C. parvum-induced Fas/FasL-dependent apoptotic cell death in bystander cells, an observation which may explain why C. parvum damage of biliary epithelia occurs almost exclusively in patients infected with HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. parvum.

C. parvum oocysts harvested from calves inoculated with a strain originally obtained from Harley Moon at the National Animal Disease Center (Ames, IA) were purchased from a commercial source (Bunchgrass Farms, Troy, ID). The oocysts were purified using a modified ether extraction protocol, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and stored at 4°C. Prior to cell culture infection, oocysts were treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite on ice for 20 min and then incubated in an excystation solution consisting of 0.75% taurodeoxycholate and 0.25% trypsin for 15 min at 37°C. The treated oocysts were then washed in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)-F12 medium (Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD), and the excysted sporozoites, intact oocysts, and empty oocysts were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. Sporozoite viability was assessed as described previously (7).

H69 cells and recombinant HIV-1 Tat protein.

The human bile duct epithelial cell line H69 is a simian virus 40-transformed cell line that was originally derived from a normal liver harvested for transplantation. H69 cells have been extensively characterized and continue to express cholangiocyte markers consistent with biliary function (20). Cells between passages 20 and 30 were used for this study. Recombinant full-length HIV-1 Tat protein (86-amino-acid peptide) was purchased from Immunodiagnostics (Woburn, MA). Tat concentrations of 100 to 500 ng/ml had no cytotoxic effects on H69 cells or on C. parvum sporozoites and were selected for this study. The concentrations used throughout this study are consistent with the concentrations used in other studies in which workers examined physiological roles of Tat in tissues, where the localized Tat concentration is expected to be slightly greater than that detected in serum from HIV-infected individuals (2 to 40 ng/ml) (43, 51).

Immunofluorescence and RT-PCR for the HIV-1 coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5.

HIV-1 infection of cholangiocytes has never been documented or demonstrated; in fact, cholangiocytes lack the HIV-1 receptor CD-4 (C. V. Paya, personal communication). Therefore, we attempted to localize the HIV-1 coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 to further demonstrate that HIV-1 cannot directly infect cholangiocytes. H69 cells and the human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29 (positive control) were grown to 70 to 80% confluence on four- or eight-well slides and processed for immunofluorescence. Briefly, the cells were fixed with 0.1 M piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) (pH 6.95), 1 mM [ethylene-bis(oxyethylenenitrilo)]tetraacetic acid, 3 mM MgSO4, and 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were incubated with mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies against CXCR4 (MCA1619) or CCR5 (MCA1835) (Serotec, Raleigh, NC), followed by fluorescein-conjugated secondary anti-mouse antibodies. The slides were then mounted with mounting medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories) and analyzed with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was also performed to detect CXCR4 and CCR5 in control cells and H69 cells. The primers used for CXCR4 were 5′-GGTGGTCTATGTTGGCGTCT-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TGGAGTGTGACAGCTTGGAG-3′ (reverse primer), and the primers used for CCR5 were 5′-TAGTCATCTTGGGGCTGGTC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TGTAGGGAGCCCAGAAGAGA-3′ (reverse primer). The amplicons were sequenced to confirm that there was target amplification. The QuantumRNA Universal 18s primer pair (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to confirm loading.

Infection assay.

H69 cells were incubated prior to C. parvum infection for at least 4 h in assay medium consisting of DMEM-F12 medium, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) in the presence or absence of Tat at a concentration of 100 to 500 ng/ml. Freshly excysted C. parvum sporozoites were resuspended in fresh medium in the presence or absence of Tat protein and added to the cell cultures at a concentration of 5 × 105 sporozoites/well (9). The infected cell cultures were incubated for 2 h, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, and processed for immunofluorescence using a C. parvum-specific polyclonal antibody, anti-CP2, as we reported previously (41). The infection percentage was determined by determining the number of infection sites in all cells in 20 fields at a magnification of ×400.

Apoptotic cytotoxicity.

A coculture system was used to examine apoptotic cytotoxicity in an infected population of cells and uninfected, cocultured, bystander cells (9). Briefly, H69 cells were grown to 70 to 80% confluence in six-well Costar tissue culture inserts (Becton Dickinson Labware) with cells both on the inserts (upper chamber) and on the plates below the inserts (lower chamber). The two cell populations were separated by a polycarbonate membrane with a high-density pore size (0.4 μm), which allowed free movement of molecules (including Tat) but not of the parasite between the upper and lower chambers. After removal of the H69 medium both cell populations were washed once in DMEM-F12 medium and resuspended in assay medium as described above. For Tat-treated cells, recombinant Tat was added to the upper chamber and allowed to equilibrate between the upper and lower chambers for 3 h to obtain a final concentration of 100 to 250 ng/ml in both the upper and lower chambers. A total of 5 × 105 sporozoites were then added to the upper chamber. After overnight incubation (∼14 h), cells in the upper and lower chambers were fixed, and apoptosis was quantified. Cells were stained with the nuclear staining dye 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (2.5 μM, 5 min) and fluorescein-labeled annexin V used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmingen) and were viewed with a fluorescence microscope. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by determining the number of apoptotic cells in all cells in 20 fields at a magnification of ×400. The numbers of cells with both positive annexin V reactions and nuclear morphology characteristic of apoptosis (i.e., condensation, margination, and/or fragmentation) were recorded (9). A control experiment was also performed, in which sporozoites were added to the upper chamber in the absence of H69 cells and cocultured with H69 cells grown on the plates in the lower chamber; the cells in the lower chamber were then assessed for apoptosis as described above. Apoptosis inhibition assays were performed in four-well slides in the presence or absence of Tat, the caspase inhibitor Z-IETD-fmk (20 mM), or the FasL antagonist antibody Nok1. Apoptotic cells were counted as described above. To confirm that there was apoptotic activity, cells were grown on a 96-well plate in the presence of Tat, C. parvum, and the FasL antagonist antibody Nok1. The Apo-ONE homogeneous caspase-3/7 assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was then performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The data below are data from experiments performed in triplicate.

Intracellular FasL expression and membrane translocation as determined by immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy.

Scanning laser confocal microscopy was used to assess the distribution of FasL in C. parvum-infected or uninfected H69 cells in the presence or absence of Tat protein. H69 cells were grown in eight-well chamber slides to 70 to 80% confluence in H69 medium. The cells were subsequently washed in DMEM-F12 medium and incubated in infection medium or infection medium containing Tat protein (100 ng/ml) for 4 h. Upon infection, C. parvum sporozoites were suspended in fresh medium or medium containing Tat and added to individual wells at a concentration of 5 × 105 sporozoites/well. The infected cultures were incubated overnight (14 h). Nonpermeabilized cells were fixed as described above and processed for immunofluorescence to reveal membrane surface labeling of FasL. Permeabilized cells were fixed as described above and subsequently treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min to reveal total FasL (both intracellular and membrane surface). The cells were then incubated with primary antibody against FasL (G247-4 [Pharmingen] or NOK-1 [BD Biosciences]) and the C. parvum-specific polyclonal antibody anti-CP2, followed by fluorescein- and rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies, respectively. The slides were then mounted as described above, and confocal scanning laser microscopy was performed using identical parameters for each treatment, which were optimized for each antibody. The contrast and intensity of each image were manipulated uniformly using the Adobe (Mountain View, CA) Photoshop software. Fluorescence intensity was determined using the Zeiss LSM510 software. Briefly, individual cells (a minimum of 50 cells for each experimental condition) were traced, and the mean value for pixel intensity was determined for the selected area. The average intensity was then determined for the population of cells from each condition. For immunogold labeling, cells were fixed and processed as described previously (15). The relative distribution of FasL was determined by counting gold particles over cell profiles; the totals are expressed below as the number of gold particles per 10 μm2. Plasma membrane labeling was quantitated by calculating the percentage of the total gold particles associated with the plasma membrane. Five uninfected H69 control images and 10 parasite infection sites were used for this analysis.

Immunoblot detection of FasL.

H69 cells were grown to 70 to 80% confluence in T25 flasks and then exposed to C. parvum in medium with or without 100 to 250 ng/ml Tat protein. After overnight infection, cells were lysed and quantitative immunoblotting was performed as previously described (9). Briefly, samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies and then with 0.2 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and were revealed by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England). The FasL antibodies C-178 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Clone 33 (Transduction Laboratories) were used to confirm FasL reactivity in the blots. The data below represent the data for immunoblots from three separate experiments. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was also utilized to confirm expression in H69 cells. The primers used for FasL were 5′-ACAACCTGCCCCTGAGCC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-AGTCTTCCTTTTCCATCCC-3′ (reverse primer), and the primers used for Fas were 5′-ACCAAGTGCAGATGTAAACC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TTCCTTTCTCTTCACCCAAAC-3′ (reverse primer). The intron-spanning amplicons were sequenced to confirm target amplification. The QuantumRNA Universal 18s primer pair (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to confirm equal loading.

To analyze the release of FasL by H69 cells in response to C. parvum infection and/or Tat treatment, H69 cells were grown to 70 to 80% confluence in T25 flasks. After overnight infection in the presence or absence of Tat protein, supernatants were collected for assays. To detect FasL in the media, the supernatants were spun at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, and 100-μl aliquots were removed and concentrated approximately 10-fold using an ultrafree concentrator with a 10,000-molecular-weight limit after 1 h of spinning at 3,000 rpm at 4°C. The concentrated supernatants were then mixed with 5× Laemmli sample buffer, boiled, and loaded into wells for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by immunoblot analysis with the FasL antibodies Clone 33 and G247-4 as described above.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed below as means ± standard errors. Means for groups were compared with Student's (unpaired) t test or an analysis of variance test where appropriate. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

H69 cells do not express HIV-1 coreceptors.

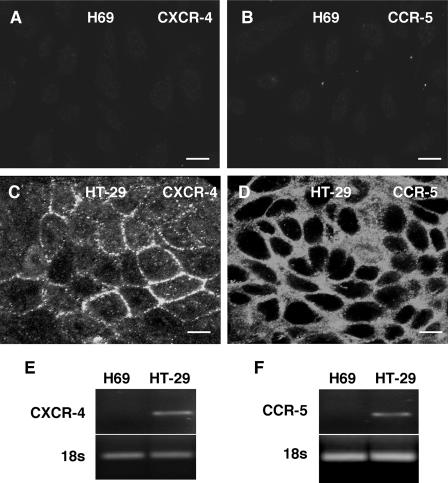

HIV-1 requires the cellular receptor CXCR4 (X4-tropic virus) or CCR5 (R5-tropic virus) for entrance into host epithelial cells (31). Using immunofluorescence microscopy, we were unable to detect either CXCR4 or CCR5 in our cultured human cholangiocytes, while control HT29 cells, which are susceptible to HIV-1 infection, expressed both receptors (Fig. 1). Furthermore, using RT-PCR, we were not able to detect the mRNA for either of these receptors in human cholangiocytes (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Expression of the HIV-1 receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in cultured human cholangiocytes (H69 cells) as determined by immunofluorescent microscopy. (A and B) No obvious staining for the CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors was observed in H69 cells. (C and D) Human colonic adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (HT-29 cells) were used as the positive control and showed a strong reaction to both CXCR4 and CCR5 antibodies, as reported by other workers. (E and F) Using RT-PCR, we could not detect the CXCR-4 and CCR-5 message in H69 cells. Our previous studies also indicated that cholangiocytes do not express CD4, another receptor required for direct HIV-1 infection. Bars = 10 μm.

Tat protein does not affect C. parvum infection of cultured cholangiocytes.

To determine if Tat protein affected C. parvum infection of cholangiocytes, H69 cells were preincubated for 4 h with 100 to 250 ng/ml Tat protein and subsequently infected with C. parvum sporozoites. Tat administration had no effect on parasite invasion of cholangiocytes (23.2% of cultured cells were infected in the presence of 100 ng/ml Tat and 21.4% of cultured cells were infected in the presence of 250 ng/ml Tat, compared with the 23.4% of cultured cells that were infected in the presence of no Tat; P > 0.05).

Tat protein potentiates C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander noninfected cholangiocytes.

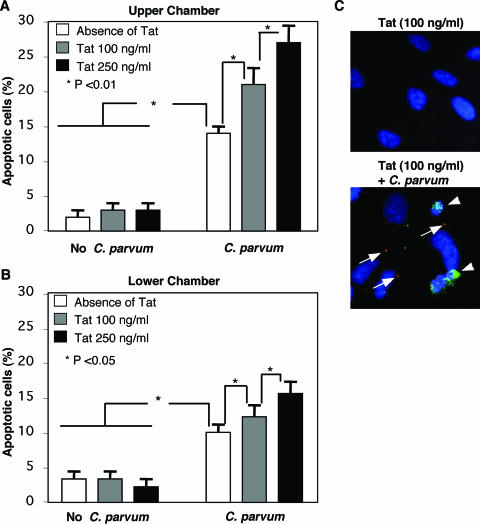

To test the potential effects of Tat treatment on C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander cholangiocytes, we used our coculture system, in which H69 cells grown in the upper chamber were exposed to C. parvum. While in this system H69 cells in the lower chamber are not directly infected by C. parvum, molecules smaller than 0.4 μm (e.g., Tat) can pass through the filter separating the two cell populations, as previously described (9). Approximately 2% of the cells in both the upper and lower chambers were found to undergo apoptosis after treatment with Tat protein (either 100 or 250 ng/ml), similar to what was observed for nontreated control cells (Fig. 2A and B). Consistent with our previous study (14), significant increases in the levels of apoptosis were detected in cells both in the upper chamber (sevenfold; P < 0.001) and in the lower chamber (fourfold; P < 0.001) when only the cells in the upper chamber were exposed to C. parvum (Fig. 2A and B). Consistently more apoptosis was detected in the upper chamber than in the lower chamber. The cells undergoing apoptosis in the upper chamber, which were directly exposed to C. parvum, were not the cells that were directly infected, as assessed by confocal microscopy using anti-CP2 antibody to C. parvum (data not shown), confirming our previous observations (14). Importantly, when the cells in the upper chamber were first treated with Tat and then exposed to C. parvum, a significant increase in the level of apoptosis was observed for cells both in the upper chamber (1.5- to 2-fold; P < 0.01) and in the lower chamber (1.3- to 1.8-fold; P < 0.01) in a Tat dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and B). In the upper chamber, apoptosis was again observed predominantly in neighboring, nondirectly infected cells (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest that Tat protein potentiates C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander noninfected cholangiocytes.

FIG. 2.

Recombinant HIV-1 Tat protein potentiates C. parvum-induced apoptosis in H69 cells in the upper and lower (uninfected bystander cells) chambers of the coculture system. (A) Cells in the upper chamber of the coculture system included both a C. parvum-infected population (approximately 25%) and an uninfected population. Tat potentiated apoptosis in the upper chamber in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Cells in the lower chamber did not interact directly with C. parvum; however, small molecules and components could freely pass through the filter separating the two populations of cells and affect cells in the lower chamber. Again, we observed a significant increase in apoptosis in cells cocultured with cells exposed to C. parvum in the upper chamber. Tat treatment further enhanced apoptosis in these cells. For the cells in the upper chamber there was consistently an increased incidence of apoptotic cells compared to the cells in the lower chamber for each condition. The data represent the results of three separate experiments for each condition. (C) Confocal immunofluorescent microscopy of apoptotic, uninfected bystander cells. The cells in which a C. parvum infection site could be demonstrated by immunofluorescence (red) (large arrows), in the presence or absence of Tat protein, were resistant to apoptosis. Neighboring uninfected cells were sensitive to apoptosis, as shown by nuclear morphology (DAPI staining) and annexin V staining (green) (small arrows).

Tat protein upregulates FasL expression in the cytoplasm of cultured cholangiocytes.

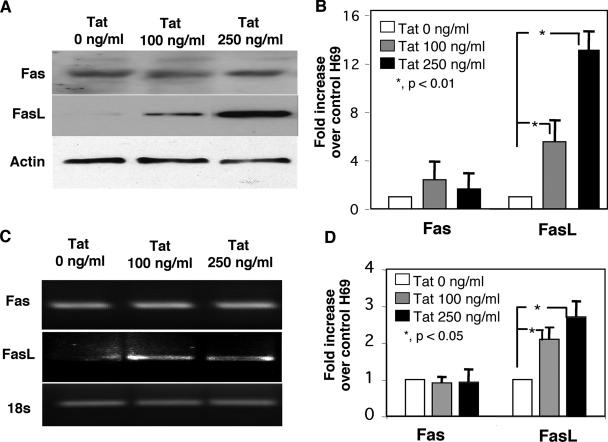

To examine how Tat potentiates C. parvum-associated apoptosis in cholangiocytes, we assessed expression of Fas and FasL in H69 cells in the presence or absence of Tat protein. As previously reported, uninfected cholangiocytes expressed both Fas protein and FasL protein (Fig. 3A). Fas protein expression did not change in cells after treatment with Tat (Fig. 3A). However, using two FasL-specific antibodies (C-178 and Clone 33), we observed a significant, dose-dependent increase in FasL protein expression in cell lysates in the presence of Tat compared to the expression in untreated cells (Fig. 3A). The results of a quantitative analysis of Fas and FasL expression by Western blotting are shown in Fig. 3B. Expression of Fas and FasL mRNA was also assessed. As previously reported, uninfected cholangiocytes expressed mRNA for both Fas and FasL (Fig. 3C). Tat treatment had no effect on Fas mRNA expression but did cause a statistically significant dose-dependent increase in FasL expression, as determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 3C). The results of a semiquantitative analysis of Fas and FasL mRNA expression for three experiments are shown in Fig. 3D.

FIG. 3.

Tat increased FasL, but not Fas, protein and mRNA expression in cultured cholangiocytes in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Fas and FasL immunoblots of cultured cholangiocyte lysates after overnight incubation in the presence of two concentrations of recombinant Tat peptide. No detectable difference in expression of the Fas receptor was observed under these conditions. Using two FasL antibodies (the results obtained with Clone 33 [Transduction Laboratories] are shown), we detected a dose-dependent increase in FasL expression in Tat-treated cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of both FasL and Fas in immunoblots from three experiments. Overnight incubation in the presence of 100 ng/ml of Tat peptide resulted in a nearly sixfold increase in FasL expression compared with the expression in untreated control cells. A dose-dependent increase in FasL expression was observed in cells treated overnight in the presence of 250 ng/ml recombinant Tat. Quantitative analysis of immunoblots of the Fas receptor from three separate experiments revealed no significant differences in expression of this receptor. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR of Fas and FasL in the presence of two concentrations of recombinant Tat peptide. No differences in expression of the Fas message were observed under these conditions. A dose-dependent increase in the FasL message was observed in Tat-treated cells. (D) Semiquantitative analysis of both Fas and FasL RT-PCR from three experiments. While no difference in expression of the Fas message was observed with either concentration of Tat peptide, a significant increase in the FasL message was observed in cells treated with 100 and 250 ng/ml Tat peptide.

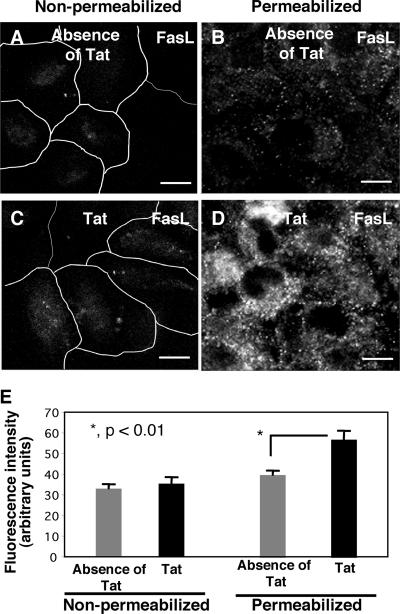

To examine the cellular distribution of FasL in cholangiocytes, we stained H69 cells with and without Tat treatment using antibodies to FasL under two different conditions: cells with membrane permeabilization in order to stain both cytoplasmic and membrane distribution and cells without membrane permeabilization in order to stain only membrane surface FasL. No detectable FasL fluorescence was observed in cells without membrane permeabilization both in the presence and in the absence of Tat (Fig. 4A and C), suggesting that there was no membrane translocation of FasL in either nontreated or Tat-treated cells. In contrast, in membrane-permeabilized cells which reflected both intracellular and membrane surface FasL, we observed a punctate, intracellular distribution of FasL in cells in the absence of Tat (Fig. 4B). Importantly, much stronger fluorescence was observed in cells in the presence of Tat, indicating that there was an increase in FasL protein expression (Fig. 4D). The results of quantification of the fluorescence intensity of FasL in confocal images are shown in Fig. 4E. The data suggest that cholangiocytes normally express a basal level of FasL in the cytoplasm and that Tat protein increases intracellular FasL expression without membrane translocation in cholangiocytes.

FIG. 4.

Tat increased intracellular FasL expression but not membrane surface expression of FasL in cultured cholangiocytes. (A and C) Non-membrane-permeabilized control H69 cells (A) and Tat-treated H69 cells (C) had minimal, similar FasL labeling on the cell surface. (B) Membrane-permeabilized control H69 cells (without Tat treatment) exhibited FasL fluorescence both in the cytoplasm and on the membrane surface. (D) Cells were treated with 100 ng/ml recombinant Tat peptide overnight and then permeabilized with Triton X-100 prior to immunofluorescence. A significant increase in FasL labeling was observed in these cells (70% increase; P < 0.01). Coupled with data for nonpermeabilized Tat-treated cells, these data suggest that Tat increases intracellular FasL expression but does not affect membrane translocation of FasL. (E) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity for nonpermeabilized cells revealed that there was no significant difference between non-Tat-treated and Tat-treated cells. The fluorescence intensity of permeabilized cells revealed that there was a significant increase in fluorescence intensity for the cells treated with 100 ng/ml recombinant Tat. Bars = 10 μm.

Tat protein enhances C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation and FasL release in infected cells.

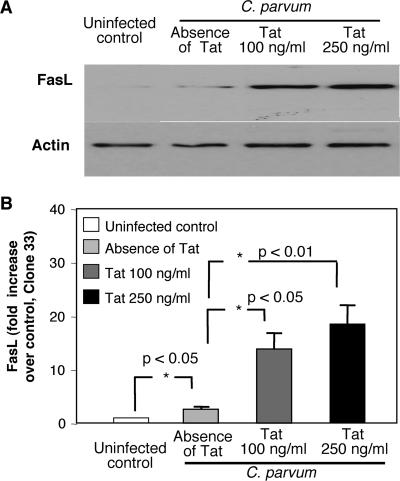

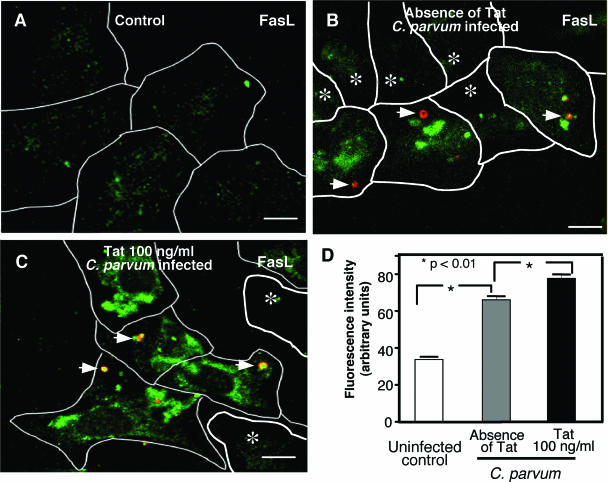

Our previous studies demonstrated that C. parvum not only upregulates FasL expression in infected cells but also causes paracrine-mediated, FasL-dependent apoptosis in bystander cells (9). To examine how C. parvum activates FasL-dependent apoptosis in bystander cells, we measured C. parvum-induced FasL protein expression and membrane translocation in infected H69 cells in the presence and absence of Tat. Consistent with our previous studies, an increase in FasL protein expression was detected in lysates of C. parvum-infected cell cultures by immunoblotting (Fig. 5A and B). Moreover, a dose-dependent, synergistic increase in FasL expression was detected in C. parvum-infected cell cultures in the presence of Tat protein (Fig. 5A and B). Using confocal microscopy of cells without membrane permeabilization, we detected a significant increase in the level of FasL on the plasma membrane in directly infected cells (Fig. 6B) compared with the level in normal control cells (Fig. 6A) or bystander, noninfected cells (Fig. 6B). Additionally, much stronger FasL membrane surface labeling was detected in C. parvum-infected cells in the presence of Tat compared with the labeling in infected cells without Tat (Fig. 6C). The results of a quantitative analysis of FasL membrane labeling are shown in Fig. 6D.

FIG. 5.

Tat enhanced C. parvum-induced FasL expression in cultured cholangiocytes. (A) FasL immunoblots of cultured cholangiocyte lysates after overnight infection in the presence or absence of recombinant Tat peptide. Two antibodies were used to assess FasL expression (the results obtained with Clone 33 [Transduction Laboratories] are shown), and both antibodies revealed an increase in FasL expression in cells exposed to C. parvum compared to the expression in uninfected control cells. C. parvum-induced FasL expression was further enhanced in the presence of Tat peptide. Actin was blotted as a loading control. (B) Quantitative analysis of immunoblots from three experiments. A modest, yet significant increase in FasL expression was observed in C. parvum-infected cells compared to the expression in uninfected control cells. The expression of FasL was significantly enhanced when the cells were infected in the presence of recombinant Tat peptide.

FIG. 6.

Tat peptide enhanced membrane translocation of FasL in C. parvum-infected cholangiocytes, as observed by confocal microscopy. Cells were processed for immunofluorescent staining without membrane permeabilization. (A) Uninfected control cholangiocytes exhibited minimal FasL surface expression. (B) C. parvum-infected cells, in the absence of Tat, exhibited aggregates of FasL fluorescence in directly infected cells (infection sites are indicated by arrowheads). (C) Tat-treated, C. parvum-infected cultured cholangiocytes exhibited robust FasL immunofluorescence (red, C. parvum; green, FasL). (D) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity for each condition confirmed the increased fluorescence of C. parvum-infected cells, which was potentiated by the presence of recombinant Tat peptide. Bars = 5 μm.

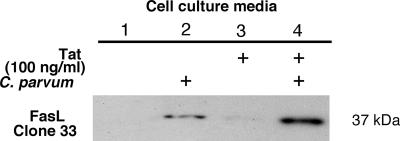

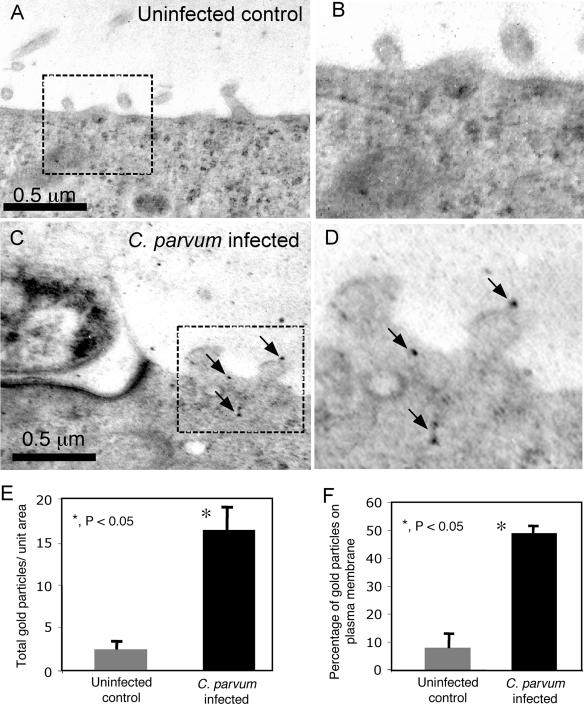

To examine whether C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation results in release of FasL from infected cells, we assessed FasL in the supernatants of cells following C. parvum infection. Cell culture supernatants were harvested after overnight infection, concentrated 10-fold, and immunoblotted for FasL expression. Two FasL-specific antibodies were used to detect FasL in the media from infected cell cultures. No FasL was detected in the media of uninfected cells (Fig. 7, lane 1). A detectable amount of full-length FasL was found in the supernatants from C. parvum-infected cells (Fig. 7, lane 2). Minimal FasL was detected in the media of cells after treatment with Tat alone (Fig. 7A, lane 3). However, significantly more FasL was detected in the supernatants of cells exposed to C. parvum and Tat than in the supernatants of cells exposed to C. parvum without Tat (Fig. 7, compare lanes 4 and 2). These data suggest that Tat protein enhances C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation and FasL release in infected cells. Immunogold electron microscopy was used to visualize the distribution of FasL in infected cells. In accordance with our fluorescence observations, very little labeling was observed in uninfected cells (Fig. 8A and B), while infected cells exhibited extensive FasL labeling on the plasma membrane and on membranous protrusions (Fig. 8C and D). The results of a quantitative analysis of gold particle distribution are shown in Fig. 8E and F. The immunogold data suggest that C. parvum infection not only upregulates FasL but also induces membrane translocation in infected cells.

FIG. 7.

Tat increased release of full-length FasL from C. parvum-infected cell cultures: representative Western blot for FasL in the supernatants after concentration with an ultrafree concentrator. An increase in the level of full-length FasL (∼37 kDa) was detected in the cell culture medium from C. parvum-infected cells compared to the cell culture medium from uninfected control cells (compare lanes 2 and 1). C. parvum infection in the presence of 100 ng/ml recombinant Tat peptide increased the amount of detectable full-length FasL compared to the amount observed for C. parvum-infected cells in the absence of Tat (compare lanes 4 and 2). Minimal FasL was detected in cell culture medium from Tat-treated cells (lane 3).

FIG. 8.

Immunoelectron microscopy. (A) Uninfected cholangiocytes exhibited minimal FasL labeling throughout the cytoplasm and plasma membrane. (B) Region of panel A enclosed in a box. (C) Infected cholangiocytes exhibited FasL labeling throughout the cytoplasm and plasma membrane. Numerous gold particles (arrows) were present on membrane extensions near the parasite. (D) Region of panel C enclosed in a box. (E) Numbers of gold particles per 10 μm2 for uninfected and infected cells. In C. parvum-infected cells there was an increase in the total amount of FasL, as observed by immunogold electron microscopy. (F) The percentage of the gold particles localized to the plasma membrane was significantly greater in infected cells than in uninfected cells. The data represent the results of an analysis of five H69 uninfected control images and 10 C. parvum infection sites.

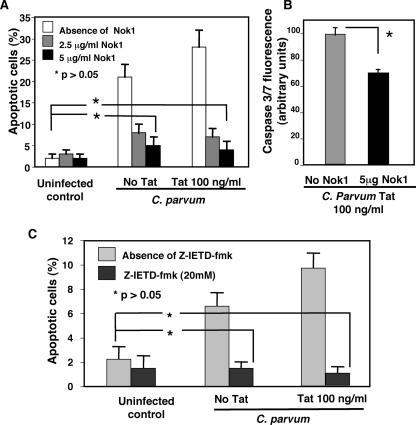

Inhibition of the Fas/FasL pathway inhibits Tat-enhanced, C. parvum-induced apoptosis.

Having established that an increase in FasL protein expression and FasL membrane translocation is associated with C. parvum infection and Tat treatment, we then asked whether inhibition of the Fas-mediated apoptotic pathway would decrease C. parvum-induced, Tat-potentiated cell death. Cells were grown to 70% confluence and incubated in the presence or absence of Tat and the NOK1 FasL antibody, a neutralizing FasL antibody that blocks FasL-induced apoptosis via inhibition of FasL binding to Fas receptors (39). Cells were then infected overnight, and apoptosis was assessed using the DAPI nuclear stain and annexin V fluorescence. Administration of 2.5 μg/ml of the NOK-1 antibody significantly inhibited C. parvum-induced apoptosis in the presence and absence of Tat (Fig. 9A). The percentage of apoptotic cells dropped to levels not significantly different from the levels for control, non-Tat-treated, uninfected cells in the presence of 5 μg/ml NOK-1 antibody for the cells treated with 100 ng/ml Tat. This observation was supported by Nok1 antibody suppression of caspase 3/7 activity (compared to the isotype control immunoglobulin G) in Tat-treated C. parvum-infected cell cultures, as determined by fluorometric analysis (Fig. 9B). To further assess the antiapoptotic effects of Fas/FasL pathway inhibition, we performed the same assay in the presence or absence of the caspase-8-specific inhibitor Z-IETD-fmk to block the function of caspase-8, a downstream effector of the Fas death signaling pathway involved in C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander cells, as previously reported (9). In the presence of 20 μM Z-IETD-fmk, the apoptosis in C. parvum-infected cells in the presence or absence of Tat was not significantly different than the apoptosis in control, non-Tat-treated, uninfected cells (Fig. 9C).

FIG. 9.

Inhibition of Fas/FasL death pathway blocks inhibited C. parvum-induced, Tat-potentiated apoptosis. After overnight incubation in the presence or absence of Tat, as well as in the presence or absence of the FasL antagonist antibody Nok1 to neutralize FasL function and Z-IETD-fmk, a specific inhibitor of caspase-8, to block activation of Fas death signaling, C. parvum-induced apoptosis was analyzed by annexin V labeling and DAPI staining. (A) In the absence of Nok1, Tat potentiated C. parvum-induced apoptosis. However, when cultures were incubated overnight in the presence of Nok1, the number of C. parvum-induced apoptotic cells decreased significantly for both the non-Tat-treated and Tat-treated populations. Administration of 5 μg/ml Nok1 to both the non-Tat-treated and Tat-treated populations decreased the incidence of apoptosis to levels not significantly different from the levels for control cells. (B) Cells treated with 100 ng/ml Tat in the absence of Nok1 antibody exhibited significantly greater caspase-3/7 activity than did cells cultured with Nok1 antibody. (C) In the absence of Z-IETD-fmk, Tat potentiated C. parvum-induced apoptosis. However, when cultures were incubated overnight in the presence of 20 μM Z-IETD-fmk, the number of C. parvum-induced apoptotic cells decreased significantly for both the non-Tat-treated and Tat-treated populations to levels not significantly different from the levels for control cells. The data represent the results of experiments performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

The results of our studies provide the first evidence suggesting that HIV-1-associated Tat protein enhances microbially induced apoptotic cell death. Using a human immortalized but nonmalignant cholangiocyte cell line, we found that (i) apoptotic cell death in bystander uninfected cholangiocytes induced by C. parvum is associated with membrane translocation in and release of full-length FasL from infected cells; (ii) whereas HIV-1-associated Tat protein alone does not cause apoptosis in uninfected cholangiocytes, Tat protein increases FasL protein expression in the cytoplasm of uninfected cholangiocytes and enhances apoptotic cell death induced by C. parvum in bystander uninfected cells; and (iii) C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation and release of full-length FasL in cholangiocytes are significantly enhanced in the presence of Tat peptide. Thus, synergistic effects of HIV-1 Tat and C. parvum biliary infection potentiate cholangiocyte injury via paracrine-mediated, Fas/FasL-dependent epithelial cell apoptosis, a process potentially involved in the pathogenesis of AIDS-related cholangiopathies.

HIV-1 infects cells via direct binding to membrane surface receptors, such as CD4 and CXCR4 and CCR5 (5). Although HIV-1 infects epithelial cells in the intestine and kidney via the CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors (33), our data indicate that cholangiocytes do not express these receptors and, therefore, are not susceptible to direct HIV-1 infection. Indeed, direct HIV-1 infection of cholangiocytes in humans has not been reported. Meanwhile, we, as well as other workers, have successfully infected cholangiocytes with C. parvum in vitro (13, 47), suggesting that C. parvum infection of cholangiocytes does not require HIV cholangiocyte infection. Here we show that Tat, a soluble 16-kDa biologically active peptide that is released from HIV-1-infected T-cells and macrophages and is essential for viral replication (2), does not affect C. parvum infection of cultured cholangiocytes. However, Tat significantly increases apoptotic cell death in uninfected cholangiocytes induced by C. parvum. Thus, whereas HIV infection may not be a prerequisite for C. parvum infection in the biliary tree, synergistic pathological effects of HIV-1 infection and C. parvum biliary infection exist and result in cholangiocyte injury via apoptosis. This finding may explain not only why C. parvum damage of biliary epithelia occurs almost exclusively in patients with HIV but also why highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with a decreased incidence of AIDS cholangiopathy.

Apoptotic cell death in AIDS patients has been reported for several cell types, including lymphocytes, neurons, endothelial and epithelial cells, and hematopoietic derived cells (38). Numerous mechanisms of HIV-induced cell death have been demonstrated, including sensitization of uninfected cells by soluble factors released from HIV-1-infected cells, including gp120, Nef, and Tat (2, 27, 44, 46). Tat appears to upregulate FasL and induces apoptosis in several cell types, including epithelial cells (4, 42). In our work, we observed a Tat-induced increase in FasL message and protein expression in uninfected cholangiocytes. Tat enhances FasL transcription through interactions with NF-κB binding sites within the FasL promoter (32). Here, we further confirmed that Tat increases FasL expression in cholangiocytes. However, Tat alone did not cause apoptosis in uninfected cholangiocytes. Moreover, the cellular distribution of FasL in Tat-treated cells as assessed by immunofluorescence revealed a cytoplasmic distribution; no increase in the level of FasL on the cell surface or in the culture medium from Tat-treated cells was detected. This observation could explain why Tat alone does not cause apoptosis in cultured cholangiocytes, since Fas/FasL-mediated cell apoptosis requires FasL membrane translocation (6, 26).

We have previously demonstrated that C. parvum infection induces apoptosis in cholangiocytes via a paracrine-mediated, Fas/FasL-dependent mechanism (9). In accordance with previous reports (14, 37), our data suggest that C. parvum induces proapoptotic activity in noninfected, neighboring cells. While Mele et al. (37) demonstrated that there was diminished apoptosis at 24-h postinfection compared to the apoptosis at earlier times, the cells undergoing apoptosis at 24 h were noninfected neighboring cells. The current study extended our previous observations and provided direct evidence of FasL membrane translocation and release of full-length FasL from directly infected cells. Membrane translocation of FasL can activate Fas receptors on adjacent cells, resulting in cell death (proximal paracrine pathway), whereas FasL released from cells can activate the Fas receptor and cause apoptosis in distant cells (distal paracrine pathway) (9); our coculture model can distinguish between these two processes. Directly infected cells in the upper chamber can cause apoptosis in bystander cells via both the proximal and distal paracrine pathways, whereas only released FasL activates apoptotic cell death in the lower chambers (only the distal paracrine pathway). Interestingly, our data suggest that while HIV-1-associated Tat protein alone does not cause apoptotic cell death in uninfected cholangiocytes, it increases FasL expression in the cytoplasm of cholangiocytes and potentiates C. parvum-induced apoptosis in bystander cholangiocytes. More importantly, Tat significantly enhances C. parvum-induced FasL membrane translocation and release of FasL from infected cells. Thus, Tat protein upregulates FasL expression but not translocation and sensitizes cholangiocytes to C. parvum-induced apoptotic cell death, suggesting that there is a synergistic effect of Tat protein with C. parvum on cholangiocyte injury via Fas/FasL-dependent apoptosis.

The mechanisms by which FasL is translocated to the membrane and released from infected cells are unclear and currently under investigation. C. parvum activates kinase pathways in infected cells (10, 11, 16); we recently demonstrated that there is recruitment of transporters and channels to the site of infection (15), consistent with the active recruitment of vesicles to the plasma membrane. It therefore seems reasonable that C. parvum-induced initiation of vesicular trafficking and membrane insertion may culminate in the shedding of FasL-bearing membrane in directly infected cells. Indeed, we observed a punctate, vesicle-like intracellular distribution of FasL in Tat-treated cholangiocytes. Immunonogold electron microscopy was used to visualize the distribution of FasL in infected cells. In accordance with our fluorescence observations, very little labeling was observed in uninfected cells, while infected cells exhibited extensive FasL labeling on the plasma membrane and on membranous protrusions. Similarly, membrane release of FasL via FasL-bearing microvesicles has been reported for other cell types, including cytolytic T cells, NK cells, epithelial ovarian cancer cells, and early trophoblast cells (1, 3, 24, 28, 36).

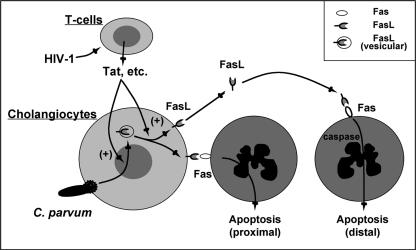

In summary, using an in vitro model of biliary cryptosporidiosis, we demonstrated that HIV-1-associated Tat protein increases FasL expression in the cytoplasm of cultured cholangiocytes. C. parvum infection induces FasL membrane translocation and release of full-length FasL in cholangiocytes and thus causes apoptotic cell death in bystander uninfected cholangiocytes, a process that is significantly enhanced in the presence of Tat protein (Fig. 10). Thus, HIV-1-associated Tat protein enhances C. parvum-induced apoptosis in cholangiocytes, a process that may contribute to the development of AIDS cholangiopathies and be relevant for other opportunistic infections in AIDS patients in general. In future studies we will focus on the molecular mechanisms of Tat-induced FasL upregulation and the parasite-initiated events responsible for the membrane translocation and release of active FasL in infected cells.

FIG. 10.

Working model of Tat-C. parvum-induced synergistic increase in cholangiocyte apoptosis. Based on previous studies and observations made in this study, we propose that C. parvum induces an increase in FasL expression in directly infected cells and promotes the release of FasL, resulting in increased apoptosis in noninfected bystander cells via activation of both Fas/FasL-induced proximal and distal paracrine pathways. While HIV-1 cannot infect cholangiocytes directly, HIV-1-infected T cells can release biologically active Tat, which potentiates C. parvum-associated apoptosis via upregulation of FasL and membrane translocation and release of FasL in infected cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. L. Splinter and P. S. Tietz for helpful and stimulating discussions and D. Hintz for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK57993 and DK24031 (to N.F.L), AI062261 (to A.D.B), DK063947 (to G.J.G.), and AI071321 (to X.-M.C.) and by the Mayo Foundation.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams, V. M., S. L. Straszewski-Chavez, S. Guller, and G. Mor. 2004. First trimester trophoblast cells secrete Fas ligand which induces immune cell apoptosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarapal, P., S. Tantivanich, K. Balachandra, K. Matsuo, P. Pitisutithum, and M. Chongsa-nguan. 2005. The role of the Tat gene in the pathogenesis of HIV infection. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 36:352-361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreola, G., L. Rivoltini, C. Castelli, V. Huber, P. Perego, P. Deho, P. Squarcina, P. Accornero, F. Lozupone, L. Lugini, A. Stringaro, A. Molinari, G. Arancia, M. Gentile, G. Parmiani, and S. Fais. 2002. Induction of lymphocyte apoptosis by tumor cell secretion of FasL-bearing microvesicles. J. Exp. Med. 195:1303-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartz, S. R., and M. Emerman. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat induces apoptosis and increases sensitivity to apoptotic signals by up-regulating FLICE/caspase-8. J. Virol. 73:1956-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger, E. A., P. M. Murphy, and J. M. Farber. 1999. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:657-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blott, E. J., G. Bossi, R. Clark, M. Zvelebil, and G. M. Griffiths. 2001. Fas ligand is targeted to secretory lysosomes via a proline-rich domain in its cytoplasmic tail. J. Cell Sci. 114:2405-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, A. T., L. J. Robertson, and H. V. Smith. 1992. Viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts: correlation of in vitro excystation with inclusion or exclusion of fluorogenic vital dyes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3488-3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao, Y. Z., D. Dieterich, P. A. Thomas, Y. X. Huang, M. Mirabile, and D. D. Ho. 1992. Identification and quantitation of HIV-1 in the liver of patients with AIDS. AIDS 6:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, X. M., G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 1999. Cryptosporidium parvum induces apoptosis in biliary epithelia by a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 277:G599-G608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, X. M., B. Q. Huang, P. L. Splinter, H. Cao, G. Zhu, M. A. McNiven, and N. F. LaRusso. 2003. Cryptosporidium parvum invasion of biliary epithelia requires host cell tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin via c-Src. Gastroenterology 125:216-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, X. M., B. Q. Huang, P. L. Splinter, J. D. Orth, D. D. Billadeau, M. A. McNiven, and N. F. LaRusso. 2004. Cdc42 and the actin-related protein/neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein network mediate cellular invasion by Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect. Immun. 72:3011-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, X. M., J. S. Keithly, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 2002. Current concepts: cryptosporidiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1723-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, X. M., and N. F. LaRusso. 2000. Mechanisms of attachment and internalization of Cryptosporidium parvum to biliary and intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 118:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, X. M., S. A. Levine, P. L. Splinter, P. S. Tietz, A. L. Ganong, C. Jobin, G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 2001. Cryptosporidium parvum activates nuclear factor kappa B in biliary epithelia preventing epithelial cell apoptosis. Gastroenterology 120:1774-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, X. M., S. P. O'Hara, B. Q. Huang, P. L. Splinter, J. B. Nelson, and N. F. LaRusso. 2005. Localized glucose and water influx facilitates Cryptosporidium parvum cellular invasion by means of modulation of host-cell membrane protrusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:6338-6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, X. M., P. L. Splinter, P. S. Tietz, B. Q. Huang, D. D. Billadeau, and N. F. LaRusso. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and frabin mediate Cryptosporidium parvum cellular invasion via activation of Cdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 279:31671-31678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark, D. P. 1999. New insights into human cryptosporidiosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:554-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimicoli, S., D. Bensoussan, V. Latger-Cannard, J. Straczek, L. Antunes, L. Mainard, A. Dao, F. Barbe, C. Araujo, L. Clement, P. Feugier, T. Lecompte, J. F. Stoltz, and P. Bordigoni. 2003. Complete recovery from Cryptosporidium parvum infection with gastroenteritis and sclerosing cholangitis after successful bone marrow transplantation in two brothers with X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 32:733-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortin, J. F., C. Barat, Y. Beausejour, B. Barbeau, and M. J. Tremblay. 2004. Hyper-responsiveness to stimulation of human immunodeficiency virus-infected CD4(+) T cells requires Nef and Tat virus gene products and results from higher NFAT, NF-kappa B, and AP-1 induction. J. Biol. Chem. 279:39520-39531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grubman, S. A., R. D. Perrone, D. W. Lee, S. L. Murray, L. C. Rogers, L. I. Wolkoff, A. E. Mulberg, V. Cherington, and D. M. Jefferson. 1994. Regulation of intracellular pH by immortalized human intrahepatic biliary epithelial-cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. 266:G1060-G1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerrant, R. L. 1997. Cryptosporidiosis: an emerging, highly infectious threat. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:51-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayward, A. R., J. Levy, F. Facchetti, L. Notarangelo, H. D. Ochs, A. Etzioni, J. Y. Bonnefoy, M. Cosyns, and A. Weinberg. 1997. Cholangiopathy and tumors of the pancreas, liver, and biliary tree in boys with X-linked immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM. J. Immunol. 158:977-983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Housset, C., E. Lamas, V. Courgnaud, O. Boucher, P. M. Girard, C. Marche, and C. Brechot. 1993. Presence of HIV-1 in human parenchymal and nonparenchymal liver cells in vivo. J. Hepatol. 19:252-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber, V., S. Fais, M. Iero, L. Lugini, P. Canese, P. Squarcina, A. Zaccheddu, M. Colone, G. Arancia, M. Gentile, E. Seregni, R. Valenti, G. Ballabio, F. Belli, E. Leo, G. Parmiani, and L. Rivoltini. 2005. Human colorectal cancer cells induce T-cell death through release of proapoptotic microvesicles: role in immune escape. Gastroenterology 128:1796-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter, P. R., and G. Nichols. 2002. Epidemiology and clinical features of Cryptosporidium infection in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:145-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaeschke, H., G. J. Gores, A. I. Cederbaum, J. A. Hinson, D. Pessayre, and J. J. Lemasters. 2002. Forum—mechanisms of hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 65:166-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeang, K. T., H. Xiao, and E. K. Rich. 1999. Multifaceted activities of the HIV-1 transactivator of transcription, Tat. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28837-28840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, J. W., E. Wieckowski, D. D. Taylor, T. E. Reichert, S. Watkins, and T. L. Whiteside. 2005. Fas ligand-positive membranous vesicles isolated from sera of patients with oral cancer induce apoptosis of activated T lymphocytes. Clin. Cancer Res. 11:1010-1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko, W. F., J. P. Cello, S. J. Rogers, and A. Lecours. 2003. Prognostic factors for the survival of patients with AIDS cholangiopathy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98:2176-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leav, B. A., M. Mackay, and H. D. Ward. 2003. Cryptosporidium species: new insights and old challenges. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:903-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, J. C. B., D. C. W. Lee, B. K. W. Cheung, and A. S. Y. Lau. 2005. Mechanisms for HIV Tat upregulation of IL-10 and other cytokine expression: kinase signaling and PKR-mediated immune response. FEBS Lett. 579:3055-3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li-Weber, M., O. Laur, K. Dern, and P. H. Krammer. 2000. T cell activation-induced and HIV Tat-enhanced CD95(APO-1/Fas) ligand transcription involves NF-kappa B. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:661-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lusso, P. 2006. HIV and the chemokine system: 10 years later. EMBO J. 25:447-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahieux, R., P. F. Lambert, E. Agbottah, M. A. Halanski, L. Deng, F. Kashanchi, and J. N. Brady. 2001. Cell cycle regulation of human interleukin-8 gene expression by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. J. Virol. 75:1736-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manabe, Y. C., D. P. Clark, R. D. Moore, J. A. Lumadue, H. R. Dahlman, P. C. Belitsos, R. E. Chaisson, and C. L. Sears. 1998. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with AIDS: correlates of disease and survival. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Lorenzo, M. J., A. Anel, S. Gamen, I. Monleon, P. Lasierra, L. Larrad, A. Pineiro, M. A. Alava, and J. Naval. 1999. Activated human T cells release bioactive Fas ligand and APO2 ligand in microvesicles. J. Immunol. 163:1274-1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mele, R., M. A. G. Morales, F. Tosini, and E. Pozio. 2004. Cryptosporidium parvum at different developmental stages modulates host cell apoptosis in vitro. Infect. Immun. 72:6061-6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura, Y., and Y. Koyanagi. 2005. Death ligand-mediated apoptosis in HIV infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 15:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nisihara, T., Y. Ushio, H. Higuchi, N. Kayagaki, N. Yamaguchi, K. Soejima, S. Matsuo, H. Maeda, Y. Eda, K. Okumura, and H. Yagita. 2001. Humanization and epitope mapping of neutralizing anti-human Fas ligand monoclonal antibodies: structural insights into Fas/Fas ligand interaction. J. Immunol. 167:3266-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Donoghue, P. J. 1995. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis in man and animals. Int. J. Parasitol. 25:139-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Hara, S. P., J. R. Yu, and J. J. C. Lin. 2004. A novel Cryptosporidium parvum antigen, CP2, preferentially associates with membranous structures. Parasitol. Res. 92:317-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peruzzi, F. 2006. The multiple functions of HIV-1 Tat: proliferation versus apoptosis. Front. Biosci. 11:708-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Re, M. C., G. Furlini, M. Vignoli, E. Ramazzotti, G. Zauli, and M. LaPlaca. 1996. Antibody against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat protein may have influenced the progression of AIDS in HIV-1-infected hemophiliac patients. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3:230-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarze, S. R., A. Ho, A. Vocero-Akbani, and S. F. Dowdy. 1999. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science 285:1569-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siliciano, R. F. 1996. The role of CD4 in HIV envelope-mediated pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. 205:159-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Townsley-Fuchs, J., M. S. Neshat, D. H. Margolin, J. Braun, and L. Goodglick. 1997. HIV-1 gp120: a novel viral B cell superantigen. Int. Rev. Immunol. 14:325-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verdon, R., G. T. Keusch, S. Tzipori, S. A. Grubman, D. M. Jefferson, and H. D. Ward. 1997. An in vitro model of infection of human biliary epithelial cells by Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1268-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wajant, H. 2002. The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science 296:1635-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westendorp, M. O., R. Frank, C. Ochsenbauer, K. Stricker, J. Dhein, H. Walczak, K. M. Debatin, and P. H. Krammer. 1995. Sensitization of T-cells to Cd95-mediated apoptosis by HIV-1 Tat and Gp120. Nature 375:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox, C. M., and K. E. Monkemuller. 1998. Hepatobiliary diseases in patients with AIDS: focus on AIDS cholangiopathy and gallbladder disease. Dig. Dis. 16:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao, H., C. Neuveut, H. L. Tiffany, M. Benkirane, E. A. Rich, P. M. Murphy, and K. T. Jeang. 2000. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11466-11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]