Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a globally distributed cause of human food-borne enteritis and has been linked to chronic joint and neurological diseases. We hypothesized that C. jejuni 11168 colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of both C57BL/6 mice and congenic C57BL/6 interleukin-10-deficient (IL-10−/−) mice and that C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice experience C. jejuni 11168-mediated clinical signs and pathology. Individually housed mice were challenged orally with C. jejuni 11168, and the course of infection was monitored by clinical examination, bacterial culture, C. jejuni-specific PCR, gross pathology, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and anti-C. jejuni-specific serology. Ceca of C. jejuni 11168-infected mice were colonized at high rates: ceca of 50/50 wild-type mice and 168/170 IL-10−/− mice were colonized. In a range from 2 to 35 days after infection with C. jejuni 11168, C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice developed severe typhlocolitis best evaluated at the ileocecocolic junction. Rates of colonization and enteritis did not differ between male and female mice. A dose-response experiment showed that as little as 106 CFU produced significant disease and pathological lesions similar to responses seen in humans. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated C. jejuni antigens within gastrointestinal tissues of infected mice. Significant anti-C. jejuni plasma immunoglobulin levels developed by day 28 after infection in both wild-type and IL-10-deficient animals; antibodies were predominantly T-helper-cell 1 (Th1)-associated subtypes. These results indicate that the colonization of the mouse gastrointestinal tract by C. jejuni 11168 is necessary but not sufficient for the development of enteritis and that C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice can serve as models for the study of C. jejuni enteritis in humans.

Campylobacter jejuni is a dominant cause of food-borne bacterial enteritis in both industrialized (17) and developing (63) nations, resulting in high levels of morbidity and economic loss. It is a ubiquitous organism occupying many environmental niches including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of many mammals. Natural infections with C. jejuni resulting in enteric disease have been reported in juvenile macaques, ferrets, dogs, cats, and swine (27, 46, 65, 73). Campylobacter jejuni demonstrates an ability to survive in many harsh environments despite its reputation as a fastidious microaerophile (18, 28). It is a naturally transformable bacterium with an epidemic population genetic structure indicative of horizontal gene transfer within and among clonal complexes within the species (11-13, 20, 43, 44, 60). These traits are suggestive of genomic and phenotypic plasticity responsive to a dynamic environment, especially the GI tract (21, 69). Genetic variation in genes associated with virulence has also been demonstrated in collections of field isolates of C. jejuni (2, 3, 10). The outcome of C. jejuni infection likely depends on many factors including the strain, dose, number, and timing of challenges; innate and adaptive immune status; passive immunity from the mother; and the presence of other enteric pathogens, commensals, and concurrent systemic infections. A mechanistic analysis of the host and bacterial factors important in C. jejuni-mediated disease requires the ability to manipulate both the host and pathogen and is best done in animal models.

A number of animal models have been used to study C. jejuni colonization and disease mechanisms. Chickens, hamsters, ferrets, dogs, primates, rabbits, mice, and pigs (4, 27, 31, 45, 49, 65, 73) have been inoculated experimentally with C. jejuni by various routes to mimic the course of infection in humans or to screen C. jejuni strains with targeted or spontaneous mutations in genes encoding such functions as chemotaxis, motility, adherence, invasion of eukaryotic cells, membrane transport, heat shock response, cytolethal toxin production, phospholipase activity, lipopolysaccharide synthesis, and two-component signal transduction (1, 16, 19, 22, 24, 27, 31, 39, 40, 56, 68, 73, 75).

Despite significant progress, a robust murine model would allow the efficient analysis of Campylobacter diversity/evolution, pathogenesis, host genetics underlying protective immunity, and therapeutic modalities after primary oral C. jejuni challenge. A number of mouse strains have been investigated as C. jejuni disease models, including BALB/c mice, C57BL/6 mice, CBA mice, DBA/2 mice, ddY mice, HA-ICR mice, and Swiss or Swiss Webster mice (4, 6, 27, 29, 36, 42, 59, 67, 73). Mice with limited enteric flora and/or with spontaneous or targeted alterations in immune function have also been explored as possible models for C. jejuni infection, including nude BALB/c mice, C3H and SCID-C3H limited-flora mice, C.B-17-SCID-beige mice, and 129 × C57BL/6 NF-κB-deficient mice (16, 40, 56, 73). Infant and adult mice have been inoculated intragastrically, intranasally, and intraperitoneally with C. jejuni for a variety of purposes including the elucidation of colonization and/or virulence mechanisms and host responses (27, 29, 30, 59, 64, 67, 73), screening of natural isolates or laboratory strains carrying spontaneous or targeted mutations that are thought to affect colonization and/or virulence (6, 27, 31, 40, 42, 56, 66, 73), and evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines or therapeutic agents (4, 36, 58, 73). However, to date, the majority of mouse models of Campylobacter infection are colonization models; if disease develops, it is inconsistent or atypical. While these models have significantly advanced the field, we sought a mouse model where the incidence of C. jejuni-induced disease was statistically robust.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is an important regulatory cytokine that suppresses effector functions of macrophages/mononuclear cells, Th1 cells, and natural killer cells (26, 51). IL-10 is produced mainly by the Th2 subset of T cells (14) and some other cell types and is important in B-cell activation essential for a successful antibody-mediated response (51). It is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that down-regulates responses against intracellular pathogens by down-regulating the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II, inhibiting the expression of T-cell costimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2 (CD80 and CD86, respectively), and inhibiting the production of gamma interferon and macrophage production of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (50). It also has an inhibitory effect on chemokines that support the inflammatory response in mouse and human cells (50). The expression of IL-10 in the GI tract is thought to be critical for the attenuation of immune system responses to normal enteric antigens at the mucosal surface (32, 50). By eliminating IL-10, one would expect to reveal proinflammatory responses generated against enteric pathogens and subsequent pathological manifestations. For instance, C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice have proved effective in the study of GI tract disease associated with Helicobacter species (15, 74). The immunological basis of Helicobacter hepaticus-associated colitis in IL-10−/− mice (33, 34), along with bacterial virulence determinants such as cytolethal distending toxin (72), has been studied extensively. Newell (53) previously suggested that the knowledge gained from the study of Helicobacter infection in mice should be directly applicable to the study of C. jejuni. In addition, IL-10−/− mice kept in housing without barriers were shown to spontaneously develop a form of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, while IL-10−/− mice kept in specific-pathogen-free facilities did not (5, 32, 34, 35). The pathogenesis of this disease likely represents an enhanced Th1 response to antigens of the enteric bacterial flora due to a lack of IL-10 that normally down-regulates such T-cell reactivity. Mechanistic studies associate uncontrolled cytokine production by activated macrophages and CD4+ Th1-type T cells with inflammatory bowel disease exhibited by IL-10−/− mice (5). Therefore, our working hypotheses were that C57BL/6 mice are susceptible to C. jejuni colonization that is stable over time and that mice of this background with an IL-10 knockout have an immune system bias that, when challenged with C. jejuni, leads to enteritis that increases in severity over time. The results presented here from time course and dose-response experiments show that C57BL/6J wild-type and congenic IL-10−/− mice are stably colonized by C. jejuni 11168 and that disease, manifested as typhlocolitis, occurs at a high rate in mice with altered immunity due to IL-10 deficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse breeding and handling.

All animal protocols were approved by the Michigan State University (MSU) All University Committee on Animal Use and Care and complied with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Handling, diet/feeding, cage changing, screening for enteric pathogens, etc., were standardized to limit exposure of the mice to extraneous microorganisms and to increase the chance that the gut flora of the mice would be stable throughout the course of the study.

C57BL/6J (IL-10+/+) and B6.129P2-IL-10tm1Cgn/J (referred to below as C57BL/6 IL-10−/−) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). A breeding colony was established in a Campylobacter/Helicobacter-free facility, and the MouSeek database (Caleb Davis, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) was used to track all mice bred and used throughout the study. Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in a FlexAir ventilated mouse rack (Alternate Design Manufacturing & Supply Inc., Siloam Spring, AR) with irradiated feed (mouse breeder diet 7904; Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN), autoclaved bedding, and filter-sterilized water (autoclaved water in bottles for weanlings) in a limited-access room at MSU. Mouse genotypes were confirmed by a PCR assay obtained from Jackson Laboratories (http://jaxmice.jax.org/pub-cgi/protocols/protocols.sh?objtype=protocol&protocol_id=346).

In addition to routine monitoring of dedicated sentinel mice for a variety of bacterial, protozoan, and viral agents through the MSU University Laboratory Animal Resources facility, we monitored the mouse colony for the incidence of spontaneous colitis by examining euthanized retired breeding mice and mice euthanized for other reasons for enlargement of the proximal colon, cecum, ileocecocolic lymph node, and spleen. Feces of mice that exhibited signs of colitis were screened for the presence of Campylobacter spp., Helicobacter spp., Enterococcus faecalis, and Citrobacter rodentium by 16S rRNA gene PCR assay for Campylobacter spp. and Helicobacter spp., espB gene-specific PCR for C. rodentium, and ddl gene-specific PCR for Enterococcus faecalis using DNA isolated from fecal pellets as described below (23, 37, 48, 57, 62). Campylobacter spp., Helicobacter spp., and C. rodentium were not detected by these PCR assays. E. faecalis was occasionally detected by PCR, although the bands were very faint (data not shown). This organism is a normal part of the fecal flora of mice and has been associated with colitis in germ-free 129SEV IL-10−/− mice (4). It was monitored because of its potential as an opportunistic pathogen.

Prior to inoculation, fecal samples were collected from one mouse in each cage and shown to be free of Campylobacter spp., Helicobacter spp., and C. rodentium by subjecting DNA isolated from the fecal pellets to a specific PCR assay as described above. Neither cultures nor PCR assays were positive for any of the four organisms tested. Mice aged 8 to 12 weeks were transported to the MSU University Research Containment Facility in autoclaved polycarbonate filter-topped cages for experiments. The mice were then housed in autoclaved polycarbonate filter-topped cages (Ancare, Bellmore, NY) on sterile bedding, fed irradiated diet 7904, and given autoclaved water and sterile cotton nestlets.

Experimental designs.

One preliminary time course experiment and two subsequent time course experiments employing C57BL/6J IL-10−/− mice and one dose-response experiment employing both C57BL/6J IL-10+/+ and C57BL/6J IL-10−/− mice were performed. All groups of mice in all experiments were composed of equal numbers of male and female mice. Each mouse received 0.2 ml of C. jejuni 11168 inoculum or tryptone soya broth (TSB) (vehicle control) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). All infected mice in the three time course experiments received approximately 1010 CFU C. jejuni 11168/mouse.

In the preliminary time course experiment, 48 mice were housed in groups of two to five mice; infected and control mice were kept in separate cages. Five male and five female infected mice and one male control mouse and one female control mouse were sacrificed on each of days 2, 10, 20, and 41 after inoculation. For the other experiments, all mice were housed individually and randomly assigned to treatments by first randomizing male and female mice separately with respect to litter by assigning each mouse a random number (generated in the random number utility of VassarStats [http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html]). The lists of mice were reordered by the assigned random numbers, and each mouse in each list was then assigned to be either infected or uninfected using a random-number table; each mouse in the infected and uninfected groups was then assigned to a treatment (time of sacrifice or dose received) using a random-number table (52). Finally, the lists of male and female mice were combined, and each cage was assigned to a position on the cage racks using a list of random numbers. For the short- and long-term time course experiments, five infected mice and three control mice of each sex were sacrificed on each of days 1 and 2 or days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 after inoculation. In the dose-response experiment, the day of sacrifice for each mouse within each group was determined by using a random-number table. One male and one female mouse of each genotype from each TSB or C. jejuni 11168 dosage group were sacrificed each day on days 35 to 39 after inoculation. Due to errors in inoculation, one IL-10−/− mouse that was assigned to receive 1010 CFU C. jejuni 11168 received 108 CFU, and one IL-10+/+ mouse that was assigned to receive 108 CFU received 1010 CFU. One mouse in the dose-response experiment was euthanized on day 6 due to clinical disease manifested by pale lungs on necropsy, and examination of a lung tissue section stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed that this mouse had pneumonia, possibly due to inhalation of the inoculum during oral gavage. Data from this mouse were not included in any analyses.

Inoculum preparation.

C. jejuni ATCC 700819 (C. jejuni NCTC 11168; hereafter referred to as C. jejuni 11168) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). A glycerol stock inoculum of C. jejuni 11168 was streaked onto tryptone soya agar (TSSBA; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep's blood (Cleveland Scientific, Bath, OH) (72), and the plates were incubated for 16 to 24 h at 37°C in a microaerobic environment in vented GasPak jars without a catalyst after evacuation to −20 mm Hg and equilibration with a gas mixture consisting of 80% N2, 10% CO2, and 10% H2. The culture was harvested with a sterile cotton swab (Puritan Medical Products, Guilford, ME) and resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.2 to 0.3 (approximate concentration, 1 × 109 CFU/ml) in TSB. Aliquots (100 μl) were spread onto TSSB agar, and the plates were incubated for 12 h at 37°C in GasPak jars equilibrated with an atmosphere of 10% CO2, 10% H2, and 80% N2. Two agar plates were prepared for each mouse to be inoculated. Bacterial growth was harvested from the agar surfaces using cell scrapers (BD Falcon, BD Biosciences, Two Oak Park, Bedford, MA) and mixed into a single master culture in TSB such that a 1:10 dilution in TSB had an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 1.0. A 10-μl aliquot of a 1:10 dilution of the master inoculum in TSB was observed by dark-field microscopy to confirm spiral cell morphology, motility, and purity of the culture. The master culture was immediately placed on ice and kept on ice throughout the inoculation process. The number of CFU in the master culture was determined by serial dilution and spreading onto TSSB agar both immediately after preparation and after inoculation of mice. Agar plates were incubated either under the atmosphere described above or in a sealed container under the atmosphere generated by a CampyGen sachet (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) for 48 h before colonies were enumerated. The inoculum for the preliminary experiment contained 4.8 × 1010 CFU/ml C. jejuni 11168 prior to inoculation and 8.0 × 1010 CFU/ml after inoculations were completed. The inoculum for the short-term time course experiment contained 4.2 × 1010 CFU/ml C. jejuni 11168 prior to inoculation and 4.7 × 1010 CFU/ml after inoculations were completed. The inoculum for the long-term time course experiment contained 6.0 × 1010 CFU/ml C. jejuni 11168 prior to inoculation and 5.4 × 1010 CFU/ml after inoculations were completed. The inocula for the dose-response experiment contained 7.4 × 1010, 6.2 × 109, 7.2 × 108, 6.3 × 107, and 6.7 × 106 CFU/ml C. jejuni 11168 for mice receiving approximate doses of 1 × 1010, 1 × 109, 1 × 108, 1 × 107, and 1 × 106 CFU/ml, respectively, prior to inoculation and 1.1 × 1011, 8.1 × 109, 6.3 × 108, 9.1 × 107, and 7.7 × 106 CFU/ml, respectively, after inoculations were completed.

Inoculation and monitoring.

Each mouse received 0.2 ml of TSB or C. jejuni 11168 inoculum delivered directly to the stomach by a sterile 3.5-Fr or 5-Fr feeding tube (Kendall Sovereign; Tyco Healthcare Group, Mansfield, MA) attached to a 1-ml Luer-Lok syringe (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After inoculation, all mice were observed at least once per day for clinical signs including inactivity, lack of responsiveness to stimulation, reduced eating or drinking, hunched posture, ruffled hair coat, dehydration, and soft feces or diarrhea. All mice exhibiting severe clinical signs were euthanized and necropsied promptly.

Necropsy and histological procedures.

A fecal sample was obtained from each mouse prior to euthanasia. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 overdose and weighed. Immediately after euthanasia, a blood sample was obtained by cardiac puncture using a 25-gauge needle on a 1-ml tuberculin syringe containing 0.1 ml 3.8% sodium citrate. Gross pathological changes were noted. The cecum, with 1 cm of terminal ileum and 1 cm of proximal colon intact, was excised from each mouse. The cecal apex was removed and placed into sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, and 0.24 g KH2PO4 per liter [pH 7.4]), and its contents were gently removed. The apex was then sectioned into halves for analysis. One half of the tissue sample was placed in a sterile cryovial and immediately frozen in an ethanol-dry ice bath. The other half was streaked over TSSBA containing 20 μg cefoperazone per ml, 10 μg vancomycin per ml, and 2 μg amphotericin B per ml (TSSBA-CVA) (72) (all antibiotics were from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the plate was incubated at 37°C under the atmosphere described above or in a sealed container under the atmosphere generated by a CampyGen sachet for 48 h. Colonization rates were ranked according to numbers of Campylobacter colonies on the plate as 0 (none), level 1 (approximately 1 to 20 CFU), level 2 (approximately 20 to 200 CFU), level 3 (over 200 CFU), and level 4 (confluent growth).

The remaining portion of the cecum was gently purged of its contents and immediately injected with 10% phosphate-buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) using a 3-ml Luer-Lok syringe and a 25-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The tissue was then placed onto a sponge in a histological cassette (Histocette II; Simport Plastics, Beloeil, Quebec, Canada) and submerged in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. After 20 to 24 h, formalin was decanted and replaced with 60% ethanol.

Small sections of the stomach, jejunum, and colon were gently purged of contents and streaked over TSSBA-CVA medium or frozen as described above for the cecal apex. All remaining portions of the GI tract and other organs from the abdominal, thoracic, and cranial cavities were placed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin in a 50-ml sterile polypropylene centrifuge tube (BD Falcon, BD Biosciences, Two Oak Park, Bedford, MA). After 20 to 24 h, formalin was decanted and replaced with 60% ethanol. Fecal samples were suspended in 200 μl TSB containing 15% glycerol, the fecal pellet was broken up with a sterile wooden applicator stick, the suspension was vortexed, and a 10-μl loopful was streaked onto TSSB-CVA agar, KF streptococcus agar for Enterococcus spp., and MacConkey agar for C. rodentium. Plasma was separated from whole blood by centrifugation; the plasma and cellular fractions were retained separately. Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin at the Investigative Histopathology Laboratory, Division of Human Pathology, Department of Physiology, Michigan State University. Sections were observed and photographed using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope with a SPOT camera with Windows version 4.09 software (RT-Slider Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

Histopathological scoring.

A scoring system was developed to evaluate histopathological changes in the ileocecocolic junction of each mouse. Specific features that were evaluated were as follows. The lumen was evaluated for excess mucus and inflammatory exudates. The epithelium was evaluated for surface integrity, number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, goblet cell hypertrophy, goblet cell depletion, crypt hyperplasia, crypt atrophy, crypt adenomatous change, and crypt inflammation. The lamina propria and submucosa were evaluated for increases in inflammatory or immune cells and their distribution; the submucosa was evaluated for fibrosis. The histological scoring sheet appears at the Michigan State University Microbiology Research Unit Food and Waterborne Diseases Integrated Research Network-sponsored Animal Model Phenome Database. All histological sections and immunohistochemically stained sections were scored by a single investigator (L. S. Mansfield) who was blinded to the identities and experimental groups of the individual mice.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed at the Investigative Histopathology Laboratory, Michigan State University. Specimens were processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned on a rotary microtome at 4-μm thickness. Sections were placed onto slides coated with 2% 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane and dried at 56°C overnight. The slides were subsequently deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated through descending grades of ethyl alcohol to distilled water. Slides were placed into Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (pH 7.5) for 5 min for pH adjustment. Following TBS incubation, antigens were retrieved from slides by utilizing citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a vegetable steamer for 30 min at 100°C, and the slides were allowed to cool on the counter at room temperature for 10 min and rinsed in several changes of distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by utilizing a 3% hydrogen peroxide-methanol bath for 30 min followed by running tap and distilled water rinses. Following pretreatment, standard avidin-biotin complex staining steps were performed at room temperature on a DAKO Autostainer (DAKO North America, Carpinteria, CA). After blocking for nonspecific protein with normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min, sections were incubated with the avidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA)-biotin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) blocking system for 15 min. Following subsequent rinsing in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.0025% Tween 20, slides were incubated for 60 min with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. jejuni (US Biologicals, Swampscott, MA) diluted 1:500 with normal antibody diluent (Scytek, Logan, UT). Slides were then rinsed in two changes of Tris-buffered saline plus 0.0025% Tween 20. After rinsing, slides were incubated for 30 min in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy plus light chains (H+L) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted in normal antibody diluent to 11 μg/ml. Slides were rinsed in TBS plus 0.0025% Tween 20, which was followed by the application of R.T.U. Vectastain Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min. The slides were rinsed with TBS plus Tween 20 and developed using Nova Red peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 15 min. At the completion of Nova Red development, slides were rinsed in distilled water, counterstained using Gill (Lerner) 2 hematoxylin (VWR Scientific, Batavia, IL) for 1.5 min, differentiated in 1% aqueous glacial acetic acid, and rinsed in running tap water. Slides were then dehydrated through ascending grades of ethyl alcohol, cleared through several changes of xylene, and coverslipped using Flotex permanent mounting medium (Lerner Laboratories, Pittsburgh, PA).

DNA extraction and PCR.

DNA was extracted from the frozen tissue samples using a DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bacterial cells were separated from the fecal samples by using a method described previously by Klijn et al. (29a); DNA was extracted from the resulting bacterial cell pellet using a DNeasy tissue kit according to the manufacturer's instructions for gram-positive bacteria. Each DNA sample was used as the template for C. jejuni-specific PCR using primers targeting the C. jejuni gyrA gene (70). PCR was performed using either puReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR beads (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) or the reaction mixture described previously by Wilson et al. (70).

ELISA.

Development of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was based on methods described previously by Fox et al. (16). The preparation of Campylobacter jejuni antigen was carried out as follows. C. jejuni 11168 was streaked onto TSSB agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h in anaerobic jars under the atmosphere generated by CampyGen sachets. Bacterial growth was harvested with cell scrapers and resuspended in PBS, and the optical density at 600 nm was determined. Protein was extracted using bacterial protein extraction reagent (B-PER; Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentration in the soluble fraction of the resulting preparation was measured using a Bradford Quick Start protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The antigen concentration was diluted to approximately 1.9 μg/ml with PBS, 100 μl of this solution was added to each well in a 96-well Nunc-Immuno MaxiSorp plate (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY), and plates were sealed with tape and incubated overnight at 4°C. The antigen solution was removed, 200 μl blocking buffer (10 mM PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween 20) was added to each well, and plates were sealed with tape and incubated overnight at 4°C. Blocking buffer was removed, and plates were washed four times with wash buffer (100 mM PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20). Control antibody solutions were diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer. Mouse plasma samples were diluted in blocking buffer as specified below; 100 μl was added to individual wells. The positive antibody control was an IgG1 monoclonal mouse anti-C. jejuni antibody (Virostat, Portland, ME), and the negative antibody control was an IgG2 monoclonal mouse anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibody (Virostat, Portland, ME). Plates were sealed with tape and incubated at room temperature for 1 h at approximately 50 rpm on a platform shaker. Sera and antibodies were removed, and plates were washed four times with wash buffer. For total IgG determinations, the secondary antibody biotinylated goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) was diluted 1:5,000 in blocking buffer, and 100 μl was added to all wells. According to the manufacturer, this antibody reacts with IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, and IgG3 heavy and light chains and light chains of IgA and IgM. For IgG subclass determinations, secondary antibodies were biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, and IgG3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). For IgA and IgM determinations, biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgA and IgM (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used. All secondary antibodies were used at the least diluted concentration recommended by the manufacturer. Plasma samples were diluted 1:200 for assays with the biotinylated goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody, 1:300 for assays with the biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG2b antibody, and 1:100 for assays with all other antibodies. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h at approximately 50 rpm on a platform shaker. Secondary antibody was removed, and plates were washed four times with wash buffer. Extravidin peroxidase solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted 1:2,000 in 10 mM PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween 20, 100 μl was added to each well, and plates were then incubated 1 h with shaking and washed four times with wash buffer. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) substrate was brought to room temperature, 100 μl was added to all wells, and the plates were tapped to mix the reagents. Plates were incubated at room temperature for approximately 10 min or until color development was sufficient. One hundred microliters of 2N H2SO4 was then added to stop the reaction. The A450 was read using a Bio-Tek EL-800 Universal plate reader using the KC Junior program (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT). Each sample was assayed in triplicate, and the average was used in further analysis. Protein concentrations in mouse plasma samples were determined by Bradford assay adapted to a microtiter plate format (http://www.animal.ufl.edu/hansen/protocols/minibradford.htm); each sample was assayed in triplicate, and the average was used in further calculations. All A450 data are adjusted on a per-microgram-of-plasma protein basis.

Statistical analysis.

Preliminary analyses of histopathological scoring data were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric one-way analysis of variance. If the result indicated that statistically significant differences existed among groups in an analysis, comparisons between groups were conducted using Fisher's exact test (K. J. Preacher [http://www.unc.edu/∼preacher/fisher/fisher.htm]). For this analysis, all control mice in an experiment were combined into a single group; scores of the infected mice that were sacrificed at a single time point or receiving a given dose of C. jejuni 11168 were compared to the combined control group by Fisher's exact test. Scores were grouped in the two-way table so that mice that had scores that fell into grade 0 (scores of ≤9) formed one class and mice that had scores that fell into grades 1 and 2 (scores of ≥10) formed the second class. After two-tailed P values were calculated using Fisher's exact test, the Holm step-down procedure was used to apply the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (38). The null hypothesis was rejected if the P value was ≤0.05.

The standard error of the mean for ELISA data was calculated using the descriptive statistics module in Microsoft Excel 2000. ELISA data contained zero values and exhibited both skewness and kurtosis; these data were transformed using the relation X′ = log(X + 1) and then analyzed using parametric tests. Linear regression was performed using utilities in Microsoft Excel; separate analyses were performed for each antibody in each experiment and for each mouse genotype in the dose-response experiment. To compare the responses of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− and IL-10+/+ mice, two-tailed t tests assuming unequal variances were performed using utilities in Microsoft Excel; separate analyses were performed for each antibody, and corrections for multiple comparisons were made using the Holm step-down procedure.

RESULTS

Mice were free of colitogenic bacteria.

All fecal samples taken from (i) experimental mice prior to the initiation of experiments, (ii) healthy mice from the breeding colony, and (iii) all mice from the breeding colony that exhibited spontaneous colitis tested negative by PCR for Campylobacter spp., Helicobacter spp., C. rodentium, and E. faecalis, except for occasional weak reactions with E. faecalis, as noted above. All DNA samples extracted from the stomach, jejunum, cecum, and colon tissues and feces of the three experimental control mice that exhibited spontaneous colitis gave negative results in the four PCR assays. The rate of spontaneous colitis in mice in the breeding colony of the same age range as the experimental mice was low: 3 of 51 mice examined (6%).

Clinical signs and gross pathology.

Mice were observed frequently for clinical signs to characterize their response to C. jejuni and to ensure that sick mice were euthanized promptly to prevent suffering. Only the infected mice with the most severe gross and histopathological lesions exhibited prominent clinical signs including inactivity, lack of responsiveness to stimulation, reduced eating or drinking, hunched posture, ruffled hair coat, soft feces or diarrhea, dehydration, and weight loss. In the long-term time course experiment, weight gain was the same in infected mice that had mild disease as in control mice (data not shown). About 20% of C. jejuni-infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice necropsied on or after day 28 after infection had severe gross pathological changes in the GI tract (Fig. 1). In these cases, the ceca and proximal colons were enlarged and fluid filled, with thickened walls. The ileocecocolic and sometimes the mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged. One infected animal in the dose-response experiment had bloody mucus in the distal colon; this mouse was euthanized on day 32 after infection due to severe disease.

FIG. 1.

Colon gross pathology in a C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse given oral Campylobacter jejuni and sacrificed 30 days after infection. (A) Normal colon from a congenic uninfected control mouse 30 days after gavage with trypticase soy broth. (B) Colon from the Campylobacter jejuni-infected mouse is enlarged and pale, with a thickened wall and watery contents.

Preliminary time course experiment.

The preliminary time course experiment was performed in order to discover an appropriate dose and time frame for subsequent work. Mice were housed in groups of two to five, segregated by sex. Thirty-nine of 40 inoculated C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice were colonized by C. jejuni 11168 based on culturing the organism from feces or from tissues taken from the stomach, small intestine, cecum, or colon and verification by C. jejuni gyrA PCR assay of whole cells from cultures and of DNA isolated from cecal tissue (data not shown). No control mice were detectably colonized. Organ-specific colonization rates (data not shown) were similar to those for the short- and long-term time course experiments shown in Fig. 2. Eight of 40 (20%) infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice developed enteritis based on the scoring of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the ileocecocolic junction using the scoring system shown in Table 1. Although there was a trend toward increasing histopathology scores with time, the scores of infected mice were not significantly different from those of control mice on any day of sacrifice. One female control mouse developed spontaneous colitis. Five infected female mice designated for euthanasia and necropsy on day 40 and housed together in a single cage all exhibited severe illness and pathology at the end of the experiment, unlike any other mice. Thus, we could not distinguish between the possibilities that (i) female mice are more susceptible to C. jejuni 11168 than male mice and/or (ii) evolution towards increased virulence occurred in the C. jejuni 11168 populations in one mouse in that cage and the hypervirulent strain was then transmitted to the other mice in the cage. Therefore, mice were individually housed in all subsequent experiments to prevent the transfer of C. jejuni 11168 between mice and to determine whether the apparent sex difference in severe disease would be expressed if mice were individually housed.

FIG. 2.

Presence of Campylobacter jejuni in four segments of the GI tract and feces in mice inoculated with C. jejuni 11168. Colonization rates were ranked according to numbers of Campylobacter colonies on the plate as 0 (none), 1 (approximately 1 to 20 CFU), 2 (approximately 20 to 200 CFU), 3 (over 200 CFU), and 4 (confluent growth). All cultures from the uninoculated control mice were negative for Campylobacter jejuni. (A to E) Short-term and long-term time course experiments. Open diamonds, male C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice; filled squares, female C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice. (F to J) Dose-response experiment. Filled diamonds, male C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice; filled squares, female C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice; open diamonds, male C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice; open squares, female C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice.

TABLE 1.

Histological scoring system

| Area | Characteristic | Description at gradea:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (score of 0-9) | 1 (score of 10-19) | 2 (score ≥20) | ||

| Lumen | Excess mucus | Absent | Present | Present |

| Inflammatory exudate | Absent | Present | Present | |

| Composition | Not applicable | Neutrophils | Neutrophils, mononuclear cells | |

| Epithelium | Surface integrity | Intact | Single or groups | Groups or ulceration |

| Goblet cell hyperplasia | Absent | Absent or slight | Variable | |

| Goblet cell depletion | Absent | Slight or moderate | Moderate or marked | |

| Crypt architecture | Normal or irregular | Irregular | Irregular | |

| Crypt dilatation | Absent | Absent | Present | |

| Crypt atrophy | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| Crypt hyperplasia | Absent or slight | Slight or moderate | Moderate or marked | |

| Crypt inflammation | Absent | Absent or single cells | Cryptitis or abscesses | |

| Composition | Not applicable | Neutrophils if present | Mononuclear cells, neutrophils | |

| Lamina propria | Cellularity | Slight | Moderate | Moderate or marked |

| Composition | Mononuclear cells | Mononuclear cells, neutrophils | Mononuclear cells, neutrophils | |

| Distribution | Focal or multifocal, occasionally diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | |

| Submucosal extension | Absent | Present | Present | |

| Submucosa | Inflammation | Absent or single cells, occasionally multiple cells | Single or multiple cells | Multiple or diffuse cells |

| Composition | Not applicable | Mononuclear cells, neutrophils | Mononuclear cells, neutrophils | |

| Fibrosis | Absent | Absent | Present | |

| Edema | Absent | Absent | Present | |

| Vasculitis | Absent | Absent | Present | |

| Red blood cells | Absent | Absent | Present | |

Characteristics that show an increase in severity over the previous grade are shown in boldface type.

Campylobacter jejuni 11168 persistently colonizes C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice.

The subsequent time course experiments were performed to determine whether C. jejuni 11168 could colonize IL-10−/− mice and, if it did colonize, how long it would persist in various compartments (stomach, jejunum, cecum, and colon) of the GI tract and be excreted in the feces. The dose-response experiment was performed in order to determine the minimum dose(s) necessary for colonization, persistence, and disease in IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice. C. jejuni 11168 was recovered from all compartments in the GI tract in both IL-10−/− and IL-10+/+ mice for 35 to 39 days after infection by culture (Fig. 2). All cultures were confirmed by C. jejuni gyrA-specific PCR assay (data not shown) (70). In addition, DNA was extracted from frozen tissue samples from the stomach, jejunum, cecum, and colon and from fecal samples taken at the time of necropsy and subjected to PCR for the C. jejuni gyrA gene (Tables 2 and 3). All control animals in all experiments were negative for C. jejuni by both culture and by PCR assay of DNA from tissue and fecal samples.

TABLE 2.

Detection of C. jejuni from various GI tract tissues of infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice by PCR specific for the C. jejuni gyrA gene in time course experimentsa

| Time course expt | Day | No. of C. jejuni-positive mice/total no. of mice

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | Jejunum | Cecum | Colon | Feces | ||

| Short term | 1 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| 2 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| Long term | 7 | 9/16 | 7/16 | 16/16 | 8/16 | 16/16 |

| 14 | 15/16 | 13/15 | 16/16 | 13/16 | 14/16 | |

| 21b | 8/17 | 9/17 | 17/17 | 15/17 | 12/15 | |

| 28c | 11/16 | 10/16 | 15/16 | 12/16 | 14/16 | |

| 35 | 5/15 | 5/15 | 15/15 | 8/15 | 15/15 | |

All control animals were negative for C. jejuni by culture and PCR.

Includes one male mouse assigned to the day 28 group that was euthanized on day 17 due to illness.

Includes one female mouse assigned to the day 35 group that was euthanized on day 28 due to illness.

TABLE 3.

Detection of C. jejuni from various GI tract tissues of infected mice by PCR specific for the C. jejuni gyrA gene in the dose-response experimenta

| Mouse strain and dose (CFU) | No. of C. jejuni-positive mice/total no. of mice

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | Jejunum | Cecum | Colon | Feces | |

| C57BL/6 IL-10−/− | |||||

| 106 | 6/10 | 7/10 | 10/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 |

| 107 | 1/10 | 3/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| 108b | 2/11 | 6/11 | 11/11 | 10/11 | 11/11 |

| 109c | 2/9 | 5/9 | 9/9 | 9/9 | 9/9 |

| 1010b | 4/9 | 5/9 | 9/9 | 8/9 | 8/9 |

| C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ | |||||

| 106 | 7/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 8/10 | 9/10 |

| 107 | 5/10 | 6/10 | 10/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 |

| 108b | 6/9 | 7/9 | 9/9 | 8/8 | 7/9 |

| 109 | 4/10 | 0/10 | 9/10 | 9/10 | 9/10 |

| 1010b | 7/11 | 7/11 | 11/11 | 11/11 | 9/11 |

All control animals were negative for C. jejuni by culture and PCR.

Due to errors in inoculation, one C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse that was assigned to receive 1010 CFU C. jejuni 11168 received 108 CFU, and one C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mouse that was assigned to receive 108 CFU received 1010 CFU.

Data do not include one C57 IL-10−/− mouse euthanized on day 6 due to pneumonia.

The cecum was the most consistently colonized site in the GI tract; the cecum was also the site harboring the highest and least variable population levels of C. jejuni 11168 in IL-10−/− mice. It is possible that the C. jejuni 11168 populations in the stomach and jejunum were maintained by coprophagy; however, in this design, mice were exposed only to their own feces. In addition, it is possible that C. jejuni 11168 populations in the colon and feces may have been derived in part from shedding from the cecum. Results from a separate but similar study indicate that C. jejuni 11168 populations associated with gently rinsed cecal tissue of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice 14 days after inoculation with 1010 CFU range from 102 to 105 CFU/mg dry cecal mass and that fecal C. jejuni populations range from 101 to 105 CFU/g dry fecal mass over the first 14 days of infection (D. L. Wilson and J. E. Linz, unpublished data). One infected mouse in the long-term time course experiment that was negative for C. jejuni by culture and PCR from cecal tissue was positive for C. jejuni 11168 by culture of jejunum tissues and feces and positive by C. jejuni gyrA-targeted PCR of DNA from stomach tissues. One infected mouse in the dose-response experiment that was negative for C. jejuni by culture and PCR from cecal tissue was positive for C. jejuni 11168 by culture and PCR of DNA from stomach tissues, by culture of jejunum tissues, and by PCR of DNA from feces.

In IL-10+/+ mice in the dose-response experiment, C. jejuni 11168 levels were generally lower in the cecum, colon, and feces than in IL-10−/− mice. There was no dose effect on C. jejuni 11168 levels in any of the compartments of the GI tracts of IL-10−/− or IL-10+/+ mice by day 35. No differences were observed between male and female mice of either IL-10 genotype.

Campylobacter jejuni 11168 causes typhlocolitis in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− but not in IL-10+/+ mice.

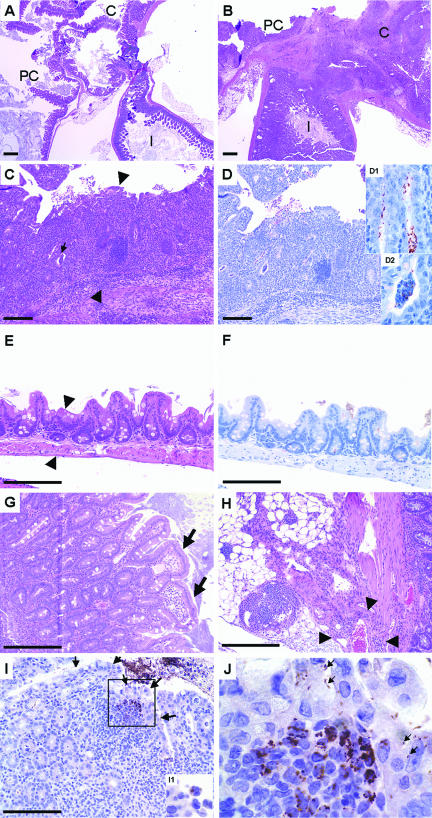

Both the time course and the dose-response experimental designs were used to assess whether C. jejuni 11168 colonization was associated with histopathological changes in the GI tract. The short-term time course experiment was performed to assess acute disease (occurring within 1 to 2 days); the long-term time course experiment was performed to assess chronic disease. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the ileocecocolic junction were systematically evaluated in a blinded fashion by a single investigator according to specific characteristics (Table 1); all layers of the intestinal wall were examined in the ileum, the cecum, and the proximal colon (Fig. 3). Total scores were apportioned into the grades shown in Table 1. About 75% of control mice had scores of ≤4 and exhibited occasional foci of mononuclear cells in the lamina propria. About 25% of control mice had scores from 5 to 9 and exhibited occasional single lesions in the epithelium, irregular crypt architecture, slight crypt hyperplasia, occasional single neutrophils in crypts, increased numbers of foci of mononuclear cells in the lamina propria, and occasional slight extension of this inflammation into the submucosa.

FIG. 3.

Representative sections of the ileocecocolic junction of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice given oral Campylobacter jejuni 11168 and sacrificed 30 days after infection. Sections are stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (A, B, C, E, G, and H) or anti-Campylobacter jejuni-specific immunohistochemical stain (D, F, I, and J). Bars represent 100 μm. (A) Low-power view (magnification, ×2) of the ileocecocolic junction of an uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− control mouse. PC, proximal colon; C, cecum; I, ileum. (B) Section (similar to A) from a C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse given oral Campylobacter jejuni. Note the extensive inflammatory response in all segments. (C) Cross section of the proximal colon from a C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse given oral Campylobacter jejuni (magnification, ×10). Note crypt hyperplasia, extensive mononuclear cell infiltrates, crypt abscesses (small arrow), and neutrophilic exudates. Arrowheads show the extent of mucosal thickening compared to panel E. (D) Serial section adjacent to the section in C that was stained with the immunohistochemical stain. Campylobacter jejuni (brown stain) can be seen in crypts (D1 inset) and crypt abscesses (D2 inset). (E) Cross section of the proximal colon from an uninfected control mouse (magnification, ×20). (F) Same cross section of the proximal colon from an uninfected control mouse stained for Campylobacter jejuni using the immunohistochemical stain, with no positive staining seen. (G) Mucosa from the ileocecocolic junction in an infected mouse showing a lesion with sloughing epithelium associated with Campylobacter jejuni infection (arrows). (H) View of mesenteries underlying the ileocecocolic junction from an infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse showing extensive mononuclear cell infiltrate, edema, and fibrosis. Arrowheads show the extent of perivascular cellular infiltrate for one vessel. (I) Low-power view (magnification, ×20) of an individual colon villus tip stained for Campylobacter jejuni. Arrows indicate the borders of the villus tip. Insert I1 shows Campylobacter jejuni within vacuoles of a phagocytic cell. (J) High-power view (magnification, ×100) of the boxed area in I. Campylobacter jejuni was associated with epithelial cells (arrows) and among and apparently inside of inflammatory cells underlying the epithelium.

IL-10−/− mice develop spontaneous colitis (9, 32) as an unregulated response to the stimulation of the immune system by the normal intestinal flora (61); this response can also be influenced by environmental factors such as diet and water (41) and manipulation of the enteric flora (54). Histopathology scores of 97% of the control mice fell into grade 0. There were 62 control mice in the four experiments combined; of these, only 2 (3%) exhibited signs of spontaneous colitis upon necropsy, including at least enlarged ileocecocolic lymph nodes and enlarged proximal colons as well as histopathological changes. The disease detected in our experiments was therefore associated with the presence of C. jejuni and was not attributable to the development of spontaneous colitis.

Mice with scores that fell into grade 1 (scores of 10 to 19) exhibited a marked increase in the severity of pathology, with changes occurring in all layers of the wall of the GI tract. Mice with scores that fell into grade 2 (scores of ≥20) exhibited an intensification of the changes seen in grade 1 along with the appearance of fibrosis, edema, perivasculitis, and extravascular red blood cells in the submucosa. The distributions of histopathology scores are shown in Fig. 4 and Tables 4 and 5. There were no differences between male and female mice in the severities of histopathology in any experiment by Fisher's exact test (all P ≥ 0.05). In the short-term time course experiment, the scores of infected mice sacrificed on day 2 but not day 1 were significantly different from those of the grouped control mice (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.019 for mice sacrificed on day 2). On day 1, one infected mouse (10%) had a score of ≥10; on day 2, 50% of the infected mice had scores falling into grades 1 and 2. In the long-term time course experiment, the scores of infected mice sacrificed on days 14, 21, 28, and 35 were significantly different from those of the grouped control mice by Fisher's exact test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.008, 0.0012, 0.0008, and 0.0005 for mice sacrificed on days 14, 21, 28, and 35, respectively). In the dose-response experiment, no control mouse had a score of ≥10. The fractions of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice with enteritis (histopathology scores of ≥10) were higher than that observed at 35 days in the time course experiment (53%) and were similar for all doses. All groups of infected mice in the dose-response experiment had histopathology scores that were different from those of the control mice (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.0005, 0.0062, 0.0004, 0.0021, and 0.0062 for C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice receiving doses of 106, 107, 108, 109, and 1010 CFU C. jejuni/mouse, respectively). Results of Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance indicated that there were no significant differences among infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice receiving different doses of C. jejuni 11168. This result indicates that the histopathological changes observed in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the time course experiments were not an artifact of the high dose (1010 CFU/mouse) used in those experiments. All C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice, both control mice and mice inoculated with all doses used, had histopathology scores of ≤5; there were no statistically significant differences among the histopathology scores of the C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice.

FIG. 4.

Histopathology scores of sections of ileocecocolic junctions from C57BL/6J IL-10−/− mice inoculated with Campylobacter jejuni 11168. Histopathology was scored as described in Materials and Methods. The bar labeled “TSB” shows data for all 32 control mice (inoculated with tryptose soya broth); the control mice were analyzed as a single group regardless of the time of sacrifice. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Campylobacter jejuni-infected animals and grouped control animals from the same experiment by Fisher's exact test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons as described in Materials and Methods. Boxes enclose data falling within the first and third quartiles of the distributions; the heavy bar within each box indicates the median of the distribution, and whisker bars indicate the maximum and minimum values observed. (A) Time course experiments. (B) Dose-response experiment.

TABLE 4.

Changes in grades of lesions of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice with timea

| Expt and group | No. of mice | No. of mice with histopathology score of grade:

|

% Enteritis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Short term | |||||

| Control (both days) | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infected at sacrifice day: | |||||

| 1 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| 2 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 50 |

| Long term | |||||

| Control (all days) | 32 | 31 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Infected at sacrifice day: | |||||

| 7 | 16 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| 14 | 16 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 38 |

| 21b | 17 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 47 |

| 28c | 16 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 50 |

| 35 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 53 |

Enteritis is defined as a histopathology score of ≥10.

Includes a mouse assigned to day 28 but euthanized on day 17 due to illness.

Includes a mouse assigned to day 35 but euthanized on day 28 due to illness.

TABLE 5.

Changes in grades of lesions with dosea

| Mouse strain, group, and dose | No. of mice | No. of mice with histopathology score of grade:

|

% Enteritis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| C57BL/6 IL-10−/− | |||||

| Control (0) | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infected | |||||

| 106 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 90 |

| 107 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 70 |

| 108 | 11b | 2 | 6 | 3 | 82 |

| 109 | 9c | 2 | 6 | 1 | 78 |

| 1010b | 9b | 3 | 5 | 1 | 67 |

| C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ | |||||

| Control (0) | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infected | |||||

| 106 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 107 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 108 | 9b | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 109 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1010b | 11b | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Enteritis is defined as a histopathology score of ≥10.

Due to errors in inoculation, one IL-10−/− mouse that was assigned to receive 1010 CFU C. jejuni 11168 received 108 CFU, and one IL-10+/+ mouse that was assigned to receive 108 CFU received 1010 CFU.

Data do not include one C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mouse euthanized on day 6 due to pneumonia.

A comparison of histopathological changes observed in different experiments and mouse genotypes is given in Table 6. The spectrum of histopathological changes observed late in infection was similar in infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice sacrificed on days 28 and 35 in the long-term time course experiment and in the dose-response experiment; however, more mice exhibited more severe changes in the dose-response experiment. Because the infection had proceeded somewhat longer in the dose response experiment (35 to 39 days compared to 28 to 35 days), this result suggests that histopathological changes might have continued to progress in all C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice if the duration of the experiments had been longer.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of histopathological changes between IL-10−/− and IL-10+/+ micea

| Characteristic | Value or description for group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection status | Infected | Infected | Infected | Infected | Infected | Infected | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Mouse genotype | IL-10−/− | IL-10−/− | IL-10−/− | IL-10−/− | IL-10+/+ | IL-10+/+ | IL-10−/− | IL-10−/− | IL-10+/+ | IL-10+/+ |

| Expt | Long-term time course | Long-term time course | Dose-response | Dose-response | Dose-response | Dose-response | Long-term time course, dose-response | Long-term time course, dose-response | Dose-response | Dose-response |

| No. of mice | 31 | 31 | 49 | 49 | 50 | 50 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 |

| Character | Mild or present | Marked | Mild or present | Marked | Mild or present | Marked | Mild or present | Marked | Mild or present | Marked |

| % of mice exhibiting characteristic | ||||||||||

| Lumen | ||||||||||

| Excess mucus | 29 | 3 | 49 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Inflammatory exudate | 29 | 16 | 59 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Compositiona | N | N/MN | N | N/MN | NA | NA | N | N | NA | NA |

| Epithelium | ||||||||||

| Surface integrity | 32 | 32 | 31 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Goblet cell hyperplasia | 26 | 6 | 53 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Goblet cell depletion | 22 | 22 | 43 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Crypt | ||||||||||

| Architecture | 61 | NA | 88 | NA | 18 | NA | 25 | NA | 10 | 0 |

| Dilatation | 7 | NA | 28 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Hyperplasia | 48 | 22 | 20 | 73 | 18 | 0 | 25 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Inflammation | 10 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Compositionb | N/MN | N/MN | N/MN | MN | NA | NA | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| Lamina propria | ||||||||||

| Cellularity | 58 | 39 | 26 | 73 | 98 | 0 | 96 | 4 | 80 | 0 |

| Compositionb | M/MN | M/MN | M/MN | M/MN | M | NA | M/MN | MN | M | NA |

| Distributionc | 26 | 71 | 16 | 84 | 98 | 0 | 92 | 8 | 80 | 0 |

| Submucosal extension | 42 | NA | 47 | NA | 0 | NA | 4 | NA | 0 | NA |

| Submucosa | ||||||||||

| Inflammation | 22 | 29 | 22 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Compositionb | M/MN | M/MN | M/MN | M/MN | NA | NA | M/MN | MN | NA | NA |

| Fibrosis | 6 | NA | 2 | NA | 0 | 0 | 4 | NA | 0 | 0 |

| Edema | 10 | NA | 12 | NA | 0 | 0 | 4 | NA | 0 | 0 |

| Perivasculitis | 13 | NA | 28 | NA | 0 | 0 | 4 | NA | 0 | 0 |

| RBCs | 13 | NA | 6 | NA | 0 | 0 | 4 | NA | 0 | 0 |

Data indicate the percentages of mice exhibiting a given characteristic. Data from the long-term time course experiment are from mice sacrificed on days 28 and 35 combined.

M, mononuclear cells; N, neutrophils; N/MN, neutrophils or mononuclear cells and neutrophils; M/MN, mononuclear cells or mononuclear cells and neutrophils; NA, not applicable; RBCs, red blood cells.

Mild, single or a few foci; marked, multiple foci or diffuse.

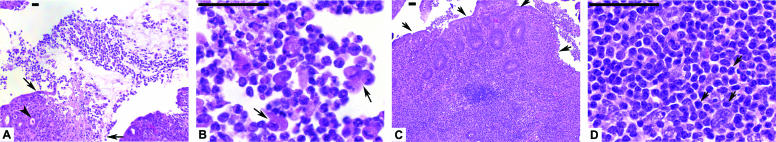

Patterns of immune cells present in GI tissues varied with infection status, among the layers of the wall of the GI tract, and between mouse genotypes. Among infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice, mild inflammatory exudates seen in the lumen were composed of neutrophils (Fig. 5); mononuclear cells were seen only in the most severe exudates; and 2 of 24 uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice (total from both time course and dose-response experiments) had neutrophils in luminal exudates. Neutrophils and mononuclear cells were seen in inflamed epithelial crypts; about half of mice that had mildly inflamed crypts had only mononuclear cells in the crypts, but all mice that had markedly inflamed crypts had both mononuclear cells and neutrophils in the crypts. A similar pattern was observed in the submucosa of infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice. No infected or uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice exhibited the presence of either mononuclear cells or neutrophils in the lumen, crypts, or submucosa. In contrast, almost all mice of both genotypes exhibited cellularity in the lamina propria. This cellularity was mild in all C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice and in 96% of uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice but was marked in 39% of infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the long-term time course experiment and 73% of infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the dose-response experiment. The infiltrate consisted strictly of mononuclear cells in all C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice and in 92% of uninfected control C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice; neutrophils were also present in about 80% of infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice but in only 8% of uninfected controls.

FIG. 5.

Representative cross sections from the ileocecocolic junctions of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice given oral Campylobacter jejuni 11168 and sacrificed 30 days after infection. Sections are stained with hematoxylin and eosin; bars represent 100 μm. (A) Low-power view (magnification, ×10) of sloughing colon villus tip from an infected mouse. Note extensive largely neutrophilic inflammatory exudates. The arrowhead shows a crypt abscess. Small arrows show the edge of the sloughing epithelium. (B) High-power view of neutrophilic inflammatory exudates from the infected mouse shown in A (magnification, ×100). Note the many neutrophils present in the exudate. Arrows show degenerating epithelial cells. (C) Colon cross section from an infected mouse showing extensive mononuclear cell infiltrates (magnification, ×10). Arrows point to the colon villus tip. (D) High-power view of mononuclear inflammatory exudates from the infected mouse shown in C (magnification, ×100). Arrows point to three of the many mononuclear cells in this field.

A comparison of uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice to uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice indicates that changes in crypt architecture and crypt hyperplasia were somewhat more prevalent in uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice (25 and 29%, respectively) than in uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice (10 and 0%, respectively), presumably due to an IL-10 deficiency in the former strain. However, these changes were still two to three times more frequent in infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice than in uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice.

Based on immunohistochemical staining, Campylobacter jejuni 11168 was found within GI tract tissues of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− but not IL-10+/+ mice.

To make a preliminary assessment of whether C. jejuni 11168 might be capable of invading intestinal tissues, immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded tissue was performed using a commercial C. jejuni-specific antiserum. Spiral-shaped organisms were seen in deep tissues (Fig. 3, D1 and D2); stained bacterial cells were also seen in paracellular junctions and at the basolateral surface of the epithelium (Fig. 3J). Immunohistochemistry of sections of the ileocecocolic junction of C. jejuni-infected mice produced nonspecific staining of the lumen contents, mucus, contents of crypts, and apical surface of the epithelium of almost all C57BL/6 IL-10−/− and IL-10+/+ mice, including control mice. C. jejuni-specific staining was seen at the basolateral surface, in the paracellular junctions of the epithelium, in crypt abscesses, and on the surface of erosive lesions and at the basolateral aspect of sloughed cells of the epithelium in 62/78 infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice from all experiments that had histopathology scores falling into grades 1 and 2. Specifically, 75% of the C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the short-term time course experiment that had histopathological scores falling into grades 1 and 2 also had C. jejuni-specific staining associated with lesions at the basolateral surface, in the paracellular junctions of the epithelium, in crypt abscesses, and under erosive lesions of the epithelium, as did 75% of such mice in the long-term time course experiment and 88% of such mice in the dose-response experiment. C. jejuni-specific staining was also observed within cells in the lamina propria and submucosa in some but not all C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice that had high histopathology scores; this staining was associated with cells that had a morphology consistent with any of the following cell types: macrophages, dendritic cells, or histiocytes.

Twenty-four of 72 (33%) infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice from all experiments with histopathology scores falling into grade 0 had C. jejuni-specific staining at the basolateral surface, in the paracellular junctions of the epithelium, in crypt abscesses, and associated with epithelial erosions. Five of the 53 (9%) experimental control C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the short-term time course, long-term time course, and dose-response experiments that had histology scores of grade 0 did have some staining at the basolateral surface, in the paracellular junctions of the epithelium, and under epithelial erosions. A single control mouse from the long-term time course experiment had severe spontaneous colitis, a histology score of grade 2, and staining in these areas. The tissues from this mouse showed significant necrosis and, thus, nonspecific staining by immunohistochemistry. All control mice tested negative for C. jejuni by both culture and PCR. Thus, there were sometimes some small areas of nonspecific staining in control mice that had to be distinguished from positive staining due to C. jejuni. The percentage of uninfected mice in the three experiments exhibiting staining at the basolateral surface, in the paracellular junctions of the epithelium, and associated with erosive and ulcerated lesions of the epithelium (6/54; 11%) was markedly smaller than the percentage of infected mice exhibiting staining in these areas: 33% of infected mice with histological scores falling into grade 0 and 75 to 88% of infected mice with histological scores falling into grades 1, 2, and 3.

Infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− and C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice exhibited a robust Th1-directed anti-C. jejuni-specific antibody response.

Both the time course and the dose-response experimental designs were used to investigate whether the mice would produce circulating anti-C. jejuni antibodies and, if so, whether the IgG isotype profiles produced by the IL-10−/− mice would reflect a Th1 immune system bias due to an IL-10 deficiency. Plasma antibody levels were measured by ELISA using secondary antibodies reacting with mouse (i) IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, and IgM; (ii) IgG1; (iii) IgG2b; (iv) IgG2c; (v) IgG3; (vi) IgA; and (vii) IgM. Antibody levels are expressed as A450 units per μg plasma protein; note that y-axis scales differ between the graphs for the different antibodies. IgG2c was measured instead of IgG2a because of the discovery that C57BL/6 mice possess this isotype in place of IgG2a (47); the B6.129P2-IL-10tm1Cgn/J mice used in these experiments have been backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background strain for at least 10 generations and are considered to be fully congenic with the background strain by the Jackson Laboratories (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/002251.html). Results are shown in Fig. 6. Levels of IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, IgG3, and IgA in the plasma of infected mice from the short-term time course experiment were very low, did not differ from those of control mice, and are not shown. IgM determinations were conducted on plasma from mice necropsied on days 1 and 2 of the short-term time course experiment and days 7, 14, and 21 of the long-term time course experiment; C. jejuni-specific IgM levels were low and similar in uninfected and infected mice within each experiment.

FIG. 6.

Antibody response as measured by ELISA. Each column indicates the mean absorbance value/μg plasma protein; error bars are standard errors. Panels A through F show results for the long-term time course experiment for total IgG, IgA, and IgM (A); IgG1 (B); IgG2b (C); IgG2c (D); IgG3 (E); and IgA (F). Panel G shows results for IgM for both short- and long-term time course experiments. Panels H through M show results for the dose-response experiment for total IgG, IgA, and IgM (H); IgG1 (I); IgG2b (J); IgG2c (K); IgG3 (L); and IgA (M). Gray bars represent values from C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice, and white bars represent values from C57BL/6 mice.

The dominant C. jejuni-specific antibody response was comprised of IgG2b. Levels of IgG1, IgG2c, IgG3, and IgA were consistently low in all mice in both the long-term time course and the dose-response experiments. IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, IgG3, IgA, and total IgG, IgA, and IgM levels exhibited statistically significant increases with time in the long-term time course experiment; the probability that the slope of the regression of antibody level against time was 0 was 1.3 × 10−5 for IgA, 0.002 for IgG1, 1.5 × 10−8 for IgG2b, 3.9 × 10−5 for IgG2c, 3.3 × 10−7 for IgG3, and 1.1 × 10−9 for total IgG, IgA, and IgM. In the C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the dose-response experiment, only IgG3 levels exhibited a statistically significant relationship with dose; the probability that the slope of the regression was zero was 0.04. However, the slope of the regression was negative due to a single high value at the dose of 1 × 106 CFU; therefore, this result is most likely not biologically meaningful. In the C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice in the dose-response experiment, IgG1, IgG2b, and total IgG, IgA, and IgM levels exhibited statistically significant relationships with dose; the probability that the slope of the regression was zero was 0.029 for IgG1, 0.028 for IgG2b, and 0.009 for total IgG, IgA, and IgM.

When antibody responses for C57BL/6 IL-10−/− and C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice were compared, responses of IL-10−/− mice were significantly different from those of IL-10+/+ mice at each of the five doses for IgG3 (two-tailed, corrected P ≤ 0.0203 for all), IgA (two-tailed, corrected P ≤ 0.0276 for all), and total IgG, IgA, and IgM (two-tailed, corrected P ≤ 0.0424 for all). Responses of IL-10−/− mice were significantly different from those of IL-10+/+ mice at doses of 1 × 106 and 1 × 107 CFU for IgG2b (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.0005 and 0.0356, respectively), at doses of 1 × 106 and 1 × 109 CFU for IgG2c (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.0.0255 and 0.0320, respectively), and at a dose of 1 × 106 CFU for IgG1 (two-tailed, corrected P = 0.0155). No other comparisons were significant at an α of 0.05. IgM levels were low and not different in control mice compared to infected mice at all time points in both the short-term and long-term time course experiments.

DISCUSSION

The overall goal of these experiments was to develop murine colonization and enteritis models of primary C. jejuni infection. Based on these data, C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ and congenic IL-10−/− mice can be used as colonization and disease models, respectively. The infectious dose needed to initiate both phenomena is low (≤106 CFU), similar to that for humans (7). Additional experiments in our laboratory have demonstrated that IL-10−/− mice of other genetic backgrounds [NOD and C3Bir.129P2(B6)] exhibit similar inflammatory processes when infected with C. jejuni 11168; these studies will be published separately. Fox and colleagues employed a similar strategy to show that mice deficient in NF-κB subunits (p50−/− p65+/−) in a C57BL/129 background were susceptible to C. jejuni (16). Taken together with previous studies on Helicobacter-associated colitis, these data and those of Fox et al. (16) on C. jejuni suggest that multiple defects in the regulation of host inflammatory processes can lead to disease and significant pathological lesions due to enteric epsilon proteobacteria. To facilitate C. jejuni studies in the C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ and congenic IL-10−/− murine models, we have produced a standard operating procedure for infection that appears at the Michigan State University Microbiology Research Unit Food and Waterborne Diseases Integrated Research Network-sponsored Animal Model Phenome Database (http://www.shigatox.net/cgi-bin/mru/mi004).

In these studies, mice were stably colonized by C. jejuni 11168. The cecum was the most consistently colonized site in the GI tract and contained the largest and least variable C. jejuni 11168 population sizes. Generally lower and more variable levels of C. jejuni 11168 were found elsewhere in the GI tract and in feces. In the dose-response experiment, 98% of C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice were colonized in the cecum 35 days after inoculation but at lower levels than in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice. This result is in accord with results from previous studies of other immunocompromised mice (16, 40). We concluded that C. jejuni 11168 colonized the GI tracts of C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ and C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice and persisted for the period of observation (maximum of 40 days). Future experiments to examine the persistence of C. jejuni 11168 in the GI tracts of C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice beyond 40 days after inoculation are planned.

Low doses of C. jejuni 11168 produced disease in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice. We expected to estimate the infectious dose from data obtained in the dose-response experiment; however, 100% of the mice of both IL-10 genotypes were colonized at the lowest dose used (approximately 106 CFU/mouse). Future experiments to determine the 50% infective dose of C. jejuni in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice are planned. Previously employed intragastric C. jejuni inocula resulting in the colonization of mice with normal intestinal flora have ranged from 106 CFU (6) to 108 to 1010 CFU (16, 29, 31, 56, 71, 73). A dose of 103 to 104 CFU was successfully used in mice with limited intestinal flora (40). The most comparable study is that by Fox et al. (16), who found that 75 and 100% of C57BL/129 NF-κB-deficient mice were colonized by wild-type C. jejuni 81-176 2 and 4 months after inoculation with 1 × 108 organisms, respectively, while 28 and 50% of wild-type C57BL/129 mice were colonized by wild-type C. jejuni 81-176 2 and 4 months after a comparable inoculation. Fox et al. (16) concluded that NF-κB was involved in the clearance of C. jejuni because fewer NF-κB-proficient than NF-κB-deficient mice remained colonized 2 and 4 months after inoculation.

The clinical signs and pathological lesions produced in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice mimicked those observed in humans and other large-animal models with enteritis due to C. jejuni. Several features of the histopathology observed in these experiments have been reported in previous studies of C. jejuni-infected humans, pigs, and other immunodeficient mouse strains (16, 27, 40, 55, 63, 73). These features include a marked lamina propria inflammation that was dominated by neutrophilic polymorphonuclear cells and mononuclear cells and that sometimes extended into the submucosa. In our disease model and in human cases, immune cells such as plasma cells, macrophages, and mononuclear cells have been found in smaller numbers in the lamina propria. Damage to, sloughing of, and ulceration of the epithelial surface and edema have also been observed in all three species. In our studies, damage to the epithelial surface was strongly associated with C. jejuni-specific immunohistochemical staining at the basolateral surface of the epithelium, in paracellular junctions of the epithelium, and in erosive and ulcerative lesions of the epithelium. In the colons of C. jejuni-infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice and neonatal pigs (45), there is often a mucopurulent neutrophilic exudate with sloughed and lysed epithelial cells and erosive or ulcerative lesions where C. jejuni is associated with the basolateral aspect of sloughing villus tip cells. Crypt abscesses and damage to the crypt epithelium in humans and mice have been observed. Hodgson et al. (25) previously observed crypt cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia in mice; Boosinger and Powe (8) previously observed perivascular neutrophils in pigs. The lesions in the cecum and proximal colon that are reported here appear to be more severe than those observed previously by Fox et al. (16); this observation may be related to the different immune alterations in the mouse strains used. The two studies also differ in the timing of the observations, since the mice in the Fox et al. (16) study were sacrificed at 8, 10, 15, and 16 weeks after infection, not 5 weeks. It is possible that C. jejuni was being cleared and inflammation was subsiding at the later time points in the Fox et al. (16) study.

Data from the short-term time course experiment suggested that C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice have acute disease (enteritis, defined as a histopathology score of ≥10) due to C. jejuni. C. jejuni 11168-infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in the long-term time course and dose-response experiments exhibited high rates of enteritis. In the long-term time course experiment, the fraction of inoculated mice exhibiting enteritis increased with time. In the dose-response experiment, 38 of 49 (78%) infected mice had enteritis. Furthermore, comparison of uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− control mice to all C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice indicated only a slightly higher degree of histopathological changes in uninfected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice due to an IL-10 deficiency under the conditions used in these studies.

Spontaneous colitis was minimal in mice in these experiments (3%). Therefore, enteritis was approximately 10 times more prevalent in mice inoculated with C. jejuni 11168 sacrificed on day 2 of the short-term time course experiment and in mice sacrificed on days 21, 28, and 35 of the long-term time course experiment than in all uninfected mice. The rate of enteritis was more than 15 times greater in mice inoculated with C. jejuni 11168 in the dose-response experiment than in all uninfected mice. Since 99% of inoculated mice were colonized by C. jejuni 11168 at high levels in the cecum, the enteritis in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice was correlated with the presence of C. jejuni 11168 in the GI tract. Therefore, we concluded that infection and subsequent colonization with C. jejuni 11168 at doses from 106 to 1010 CFU/mouse led to enteritis in approximately 50 to 80% of inoculated C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice in 28 to 35 days and that this enteritis was not due to the development of spontaneous colitis. Furthermore, the histological changes observed in C. jejuni 11168-infected C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice were similar to those in immunocompetent humans and pigs and in other immunodeficient mouse strains described previously.

Both C57BL/6 IL-10−/− and C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ mice exhibited a robust Th1-directed antibody response (predominantly IgG2b) to infection with C. jejuni 11168; Fox et al. (16) also described a Th1-directed antibody response in NF-κB-deficient mice. IgG1 levels, which would be indicative of a Th2-directed response, were low in all mice. As expected, plasma anti-C. jejuni-specific antibody levels increased with time in C57BL/6 IL-10−/− mice. As in the colonization and histopathology studies, we did not observe consistent relationships between plasma antibody levels and doses of C. jejuni 11168. In the dose-response experiment, the IgG subclass antibody responses of the two mouse genotypes were not consistently different from each other. We conclude that C57BL/6 IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice react to C. jejuni 11168 by producing specific IgG antibody that does not protect against enteritis in the context of an IL-10 deficiency. Taken together with our observation that C57BL/6 IL-10−/− but not C57Bl/6 IL-10+/+ mice exhibited histopathological changes when infected with C. jejuni 11168 and with the observations of C. jejuni 81-176-infected NF-κB-deficient mice reported previously by Fox et al. (16), this result suggests that the primary mediator(s) determining colonization and disease outcomes in this mouse model is likely to be anti-inflammatory regulators such as IL-10 and not circulating antibodies.