Abstract

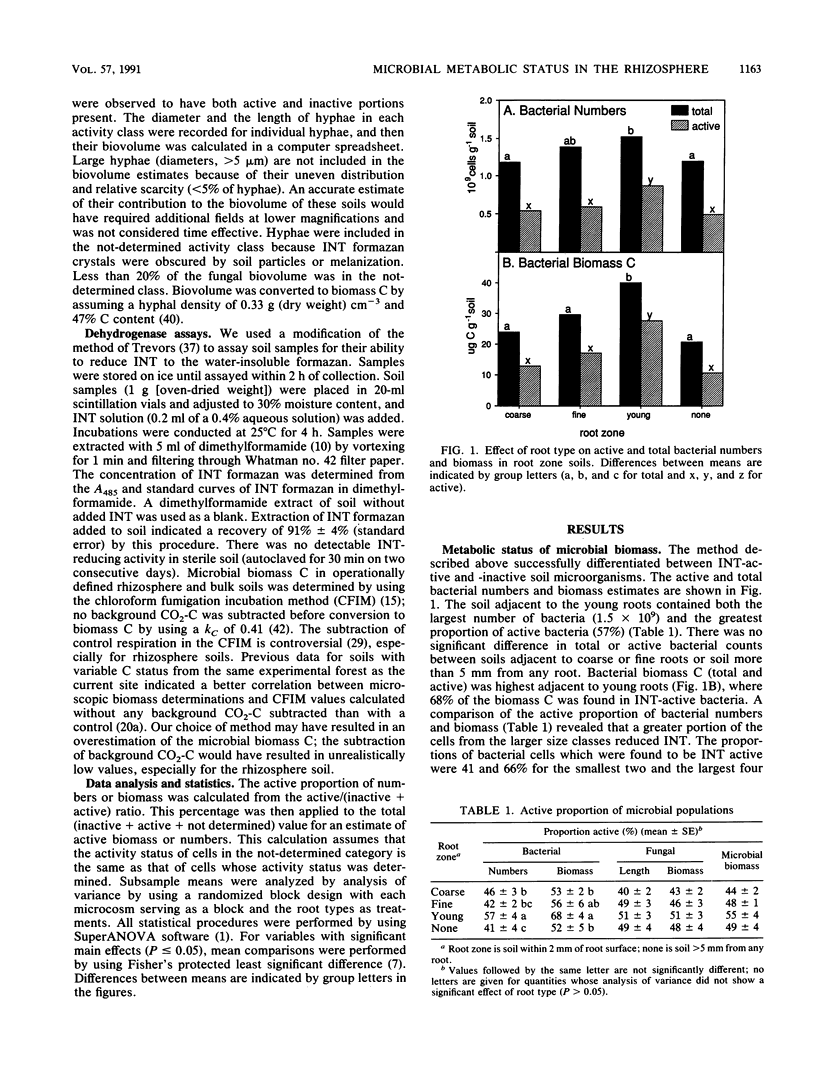

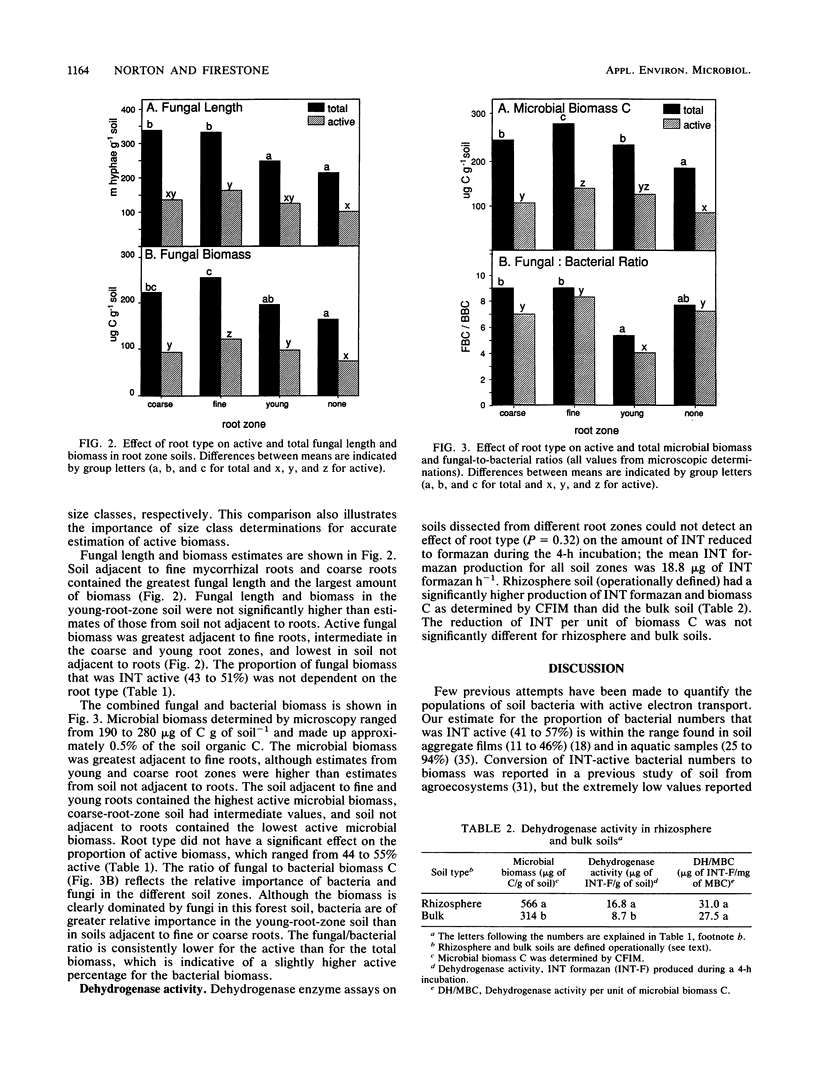

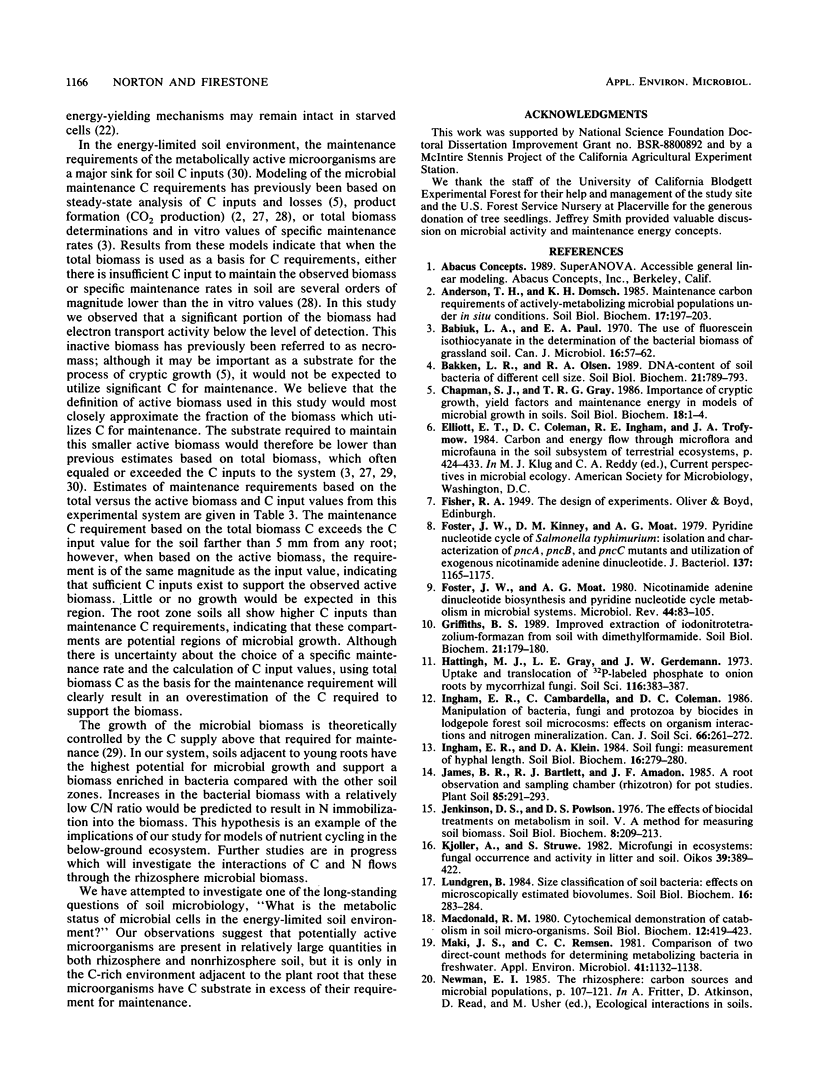

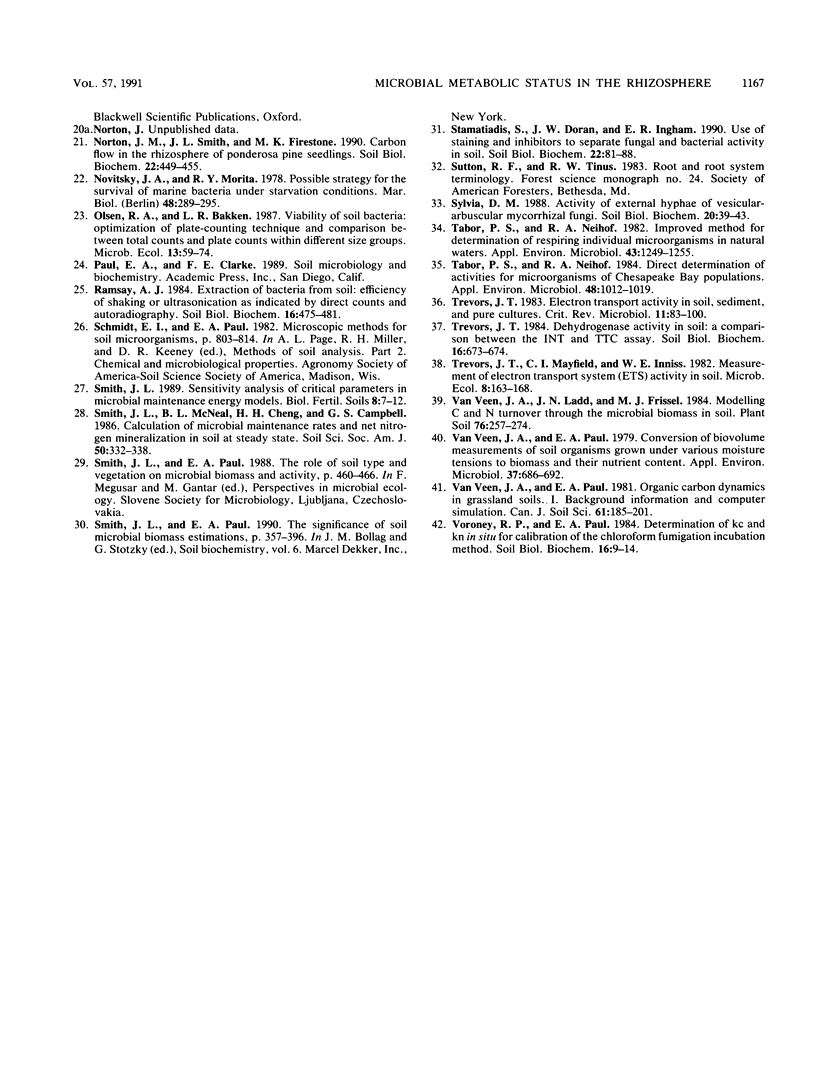

We determined the quantity and metabolic status of bacteria and fungi in rhizosphere and nonrhizosphere soil from microcosms containing ponderosa pine seedlings. Rhizosphere soil was sampled adjacent to coarse, fine, or young roots. The biovolume and metabolic status of bacterial and fungal cells was determined microscopically and converted to total and active biomass values. Cells were considered active if they possessed the ability to reduce the artificial electron acceptor 2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride (INT) to visible intracellular deposits of INT formazan. A colorimetric assay of INT formazan production was also used to assess dehydrogenase activity. INT-active microorganisms made up 44 to 55% of the microbial biomass in the soils studied. The proportion of fungal biomass that exhibited INT-reducing activity (40 to 50%) was higher than previous estimates of the active proportion of soil fungi determined by using fluorescein diacetate. Comparison between soils from different root zones revealed that the highest total and INT-active fungal biomass was adjacent to fine mycorrhizal roots, whereas the highest total and active bacterial biomass was adjacent to the young growing root tips. These observations suggest that fungi are enhanced adjacent to the fine roots compared with the nonrhizosphere soil, whereas bacteria are more responsive than fungi to labile carbon inputs in the young root zone. Colorimetric dehydrogenase assays detected gross differences between bulk and rhizosphere soil activity but were unable to detect more subtle differences due to root types. Determination of total and INT-active biomass has increased our understanding of the role of spatial compartmentalization of bacteria and fungi in rhizosphere carbon flow.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Babiuk L. A., Paul E. A. The use of fluorescein isothiocyanate in the determination of the bacterial biomass of grassland soil. Can J Microbiol. 1970 Feb;16(2):57–62. doi: 10.1139/m70-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. W., Kinney D. M., Moat A. G. Pyridine nucleotide cycle of Salmonella typhimurium: isolation and characterization of pncA, pncB, and pncC mutants and utilization of exogenous nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. J Bacteriol. 1979 Mar;137(3):1165–1175. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1165-1175.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. W., Moat A. G. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis and pyridine nucleotide cycle metabolism in microbial systems. Microbiol Rev. 1980 Mar;44(1):83–105. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.1.83-105.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki J. S., Remsen C. C. Comparison of two direct-count methods for determining metabolizing bacteria in freshwater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 May;41(5):1132–1138. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.5.1132-1138.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor P. S., Neihof R. A. Direct determination of activities for microorganisms of chesapeake bay populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Nov;48(5):1012–1019. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.1012-1019.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor P. S., Neihof R. A. Improved method for determination of respiring individual microorganisms in natural waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Jun;43(6):1249–1255. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.6.1249-1255.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevors J. T. Electron transport system activity in soil, sediment, and pure cultures. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1984;11(2):83–100. doi: 10.3109/10408418409105473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen J. A., Paul E. A. Conversion of biovolume measurements of soil organisms, grown under various moisture tensions, to biomass and their nutrient content. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Apr;37(4):686–692. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.4.686-692.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]