Abstract

Twenty Gateway-compatible destination vectors were constructed. The vectors comprise fluorescent and epitope fusion tags, various drug markers, and replication origins that should make them useful for exploring existing microbial ORFeomes. In an attempt to validate several of these vectors, we observed polar and oscillating localization of MinD in Brucella abortus.

ORFeomes are comprehensive collections of predicted coding sequences or open reading frames (ORFs) of a given organism (3). The availability of complete bacterial ORFeomes such as those described for Brucella melitensis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Sinorhizobium meliloti (6, 14, 18) (other bacterial ORFeomes are available at the TIGR resources: http://pfgrc.tigr.org/) require plasmidic tools to study biological functions of ORFs at proteomic levels, such as interactomes and localizomes (13, 15). Since the constructions of ORFeomes cited above were based on the site-specific integration/excision reactions used by bacteriophage λ and called “Gateway recombinational cloning” (8, 23), we designed three sets of Gateway-compatible destination vectors useful for functional analyses of these bacterial ORFeomes.

The first set was designed for complementation of loss-of-function mutants and for constitutive overexpression of ORFs. The second set allows translational fusion with fluorescent proteins (cyan fluorescent protein [CFP], yellow fluorescent protein [YFP], and enhanced green fluorescent protein [EGFP]) for determining subcellular localization and colocalization of proteins. The last set of vectors provide translational fusions to tag coding sequences (21, 22), therefore making them useful for in vivo coexpression of ORFs and/or coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Integrative versions of these plasmids were also constructed to allow expression of a tagged ORF under the control of its native promoter. A detailed description of plasmid constructions is provided in the supplemental material. All plasmids reported here are available from the Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms (BCCM/LMBP plasmid collection) (http://bccm.belspo.be/about/lmbp.php).

Expression vectors.

Vectors described in this section were designed for functional complementation assays or constitutive overexpression of bacterial ORFs. Destination vectors pRH001, pRH002, and pRH003 were obtained by cloning the Gateway cassette reading frame B into pMR10cat, pBBR1-MCS1, and pBBR1-MCS4, respectively (Table 1). The orientation of the Gateway cassette in these three destination vectors was selected to ensure that ORFs were placed under the control of the Escherichia coli lac promoter after attL-attR (LR) reactions. pRH001 (previously named pMR10cat Gateway) was validated in previous work using complementation assays (5, 7). The transcriptional regulators ArsR6 and GntR4 were identified to control the expression of the virB operon since no VirB proteins could be detected in the corresponding ΔarsR6 and ΔgntR4 mutants (7). Expression of arsR6 and gntR4 from pRH001-arsR6 and pRH001-gntR4 completely restored the wild-type level of production of VirB9, one of the 11 proteins encoded by the virB operon (7). pRH001-rsh was also used to perform a heterospecific complementation of an S. meliloti relA mutant with the orthologous B. melitensis rsh (5). From these data we can conclude that pRH001 is functional for performing complementation of loss-of-function mutants, at least in bacterial species in which the E. coli lac promoter is functional.

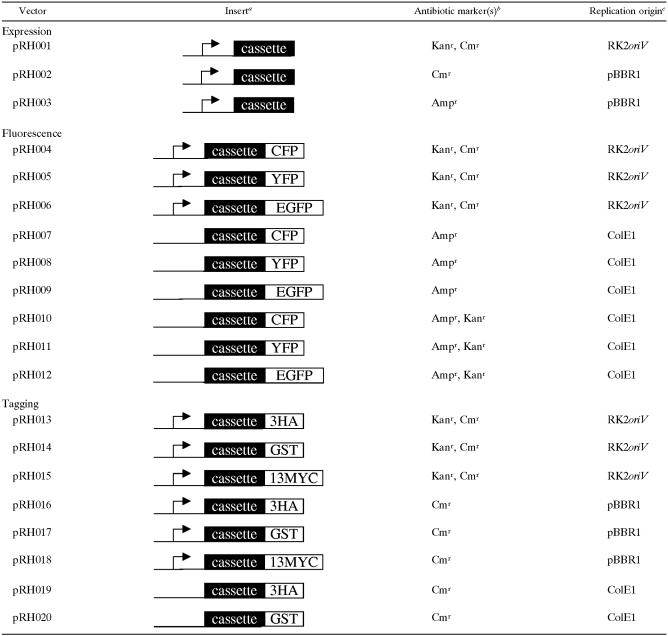

TABLE 1.

Destination vectors described in this study

Arrows illustrate the E. coli lac promoter. “Cassette” means a Gateway cassette comprising attR1, cat, ccdB, and attR2.

Kanr, Cmr, and Ampr are antibiotic markers which confer resistance to kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and ampicillin, respectively.

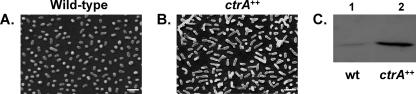

We used the Y-shape phenotype displayed by Brucella overexpressing the response regulator CtrA (2) to test the functionality of pRH002 and pRH003 for overexpressing ORFs. As expected, B. abortus wild-type strain cells expressing ctrA from pRH002-ctrA and pRH003-ctrA are branched and larger than the wild-type control (Fig. 1A and B and data not shown), as previously described (2). The level of expression of CtrA from these two plasmids in B. abortus was also compared to the wild-type CtrA level by Western blotting (Fig. 1C and data not shown). From these experiments we can conclude that pRH002 and pRH003 can be used to overexpress ORFs.

FIG. 1.

Overexpression of ctrA in Brucella abortus leads to large Y-shaped bacteria. Shown are scanning electron micrographs of the B. abortus 544 wild-type strain (A) and a strain overexpressing ctrA from pRH002 (B). The scale bar represents 2 μm. (C) The overproduction of CtrA in a strain containing pRH002 (lane 2) was monitored by Western blotting using anti-CtrA antibodies, as previously described (2), with the wild-type (wt) strain as a control (lane 1). The same amount of proteins was loaded in each well.

Fluorescence vectors.

An increasing number of bacterial proteins have been reported in the past decade to be localized at discrete locations in bacteria (10, 11, 19). In order to determine the subcellular localization of bacterial proteins by direct fluorescence microscopy, we designed the second set of destination vectors (Table 1). These destination vectors allow the expression of fusions of ORF-encoded proteins to the N termini of fluorescent proteins. All fluorescence destination vectors described in this section are derived from pMR10cat, and the Gateway cassette in frame with cfp, yfp, or egfp was placed in the same orientation as the E. coli lac promoter.

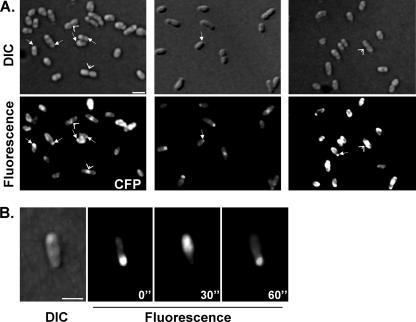

Selection of the proper division site at midcell in bacteria such as E. coli requires the specific inhibition of septation at poles. This is mediated by the coordinated action of MinC, MinD, and MinE proteins. The division inhibition complex MinC/MinD, restricted to cell poles through the action of the topological specificity factor MinE, avoids the formation of a polar Z ring (4). In this system, MinD supplies polar localization (16, 17). We therefore tested if minDBm (BMEII0926 in the B. melitensis genome; AAL54168 in GenBank) encodes a protein localized at a pole(s) in B. abortus. To this end, we transferred minDBm from the pDONR201-minD entry clone available in the Brucella ORFeome (6) into pRH004, pRH005, and pRH006. The products of the LR reactions, performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen), were electroporated into E. coli DH10B and selected on Luria-Bertani plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). Plasmids pRH004, pRH005, and pRH006, expressing minDBm, were then transferred by conjugation into B. abortus 544. The mid-exponential-phase cultures of three independent clones expressing minDBm on pRH004, pRH005, and pRH006 were embedded in a 1% agarose pad on microscope slides as previously described (9). Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images were then acquired using Nikon E1000 microscope with the corresponding filter cubes.

As illustrated in Fig. 2A, B. abortus producing MinDBm-CFP, MinDBm-YFP, or MinDBm-EGFP showed fluorescent signals in the form of an arc following the line of the pole or polar focus (Fig. 2A, arrows) at either one or both poles in more than 90% of the bacteria examined. This is consistent with the localization of MinD described for other bacterial species such as E. coli (17) or Bacillus subtilis (16). Moreover, images taken at 30-second intervals of the same field indicated that MinDBm in B. abortus is polarly localized in a dynamic fashion by oscillating from one pole to the opposite pole, as was described for E. coli but not for B. subtilis (Fig. 2B). Similar observations were made when MinDBm was localized in the B. melitensis 16 M wild-type strain (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

MinD is dynamically localized at the cellular pole(s) in B. abortus. (A) B. abortus 544 wild-type strains expressing minDBm fused in frame with cfp, yfp, and egfp from pRH004, pRH005, and pRH006, respectively, were cultivated in rich liquid medium until mid-exponential phase before samples were prepared for examination under a fluorescence microscope as previously described by Jacobs et al. (9). DIC and corresponding fluorescent images are presented. White arrows indicate polar localization of MinDBm, while arrowheads show midcell localization. (B) Representative time-lapse fluorescence microscopy experiment on a B. abortus 544 cell containing pRH005 plasmid-encoded MinDBm-YFP. DIC and fluorescent images were taken every 30 seconds. Scale bar, 1 μm.

We could observe in some bacterial cells a helical pattern of MinDBm localization (data not shown), which has already been described for E. coli (20). Finally, in most cells at a late stage in the cell division process, a discrete fluorescence signal at the center of dividing cells was observed (Fig. 2A, arrowheads). This suggests that MinDBm does not localize dynamically only at old poles, probably to inhibit formation of mislocalized Z ring (i.e., polar Z ring), but also at division sites before completion of cell constriction, probably to prevent another division from taking place near the newly formed poles. It was previously found that MinD is targeted to old and newly formed poles in B. subtilis (16).

These results demonstrated that (i) pRH004, pRH005, and pRH006 can be used for determining the subcellular localization of bacterial proteins and that (ii) MinDBm is polarly localized and oscillates from one pole to the other in B. abortus, as previously shown for E. coli.

Tagging vectors.

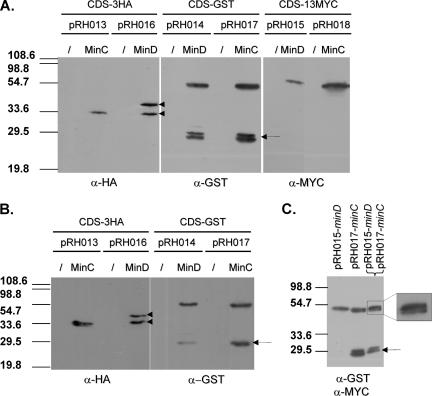

Studying biological functions of a gene product requires understanding the complex network(s) in which it is directly implicated. In this context, mapping physical protein-protein interactions is an important step. Yeast two-hybrid vectors are already available in a Gateway-compatible format (15), and here we describe vectors allowing protein tagging, and therefore high-throughput coimmunoprecipitation or pull-down tests. The first six tagging destination vectors are derived from pMR10cat (pRH013 to pRH015) and pBBR1-MCS1 (pRH016 to pRH018). These vectors allow expression of protein-coding ORFs in frame with three repetitions of a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (3HA in pRH013 and pRH016), glutathione S-transferase (GST in pRH014 and pRH017), or 13 repetitions of the MYC epitope (13MYC in pRH015 and pRH018) under the control of the E. coli lac promoter. We assayed the tagging destination vectors (pRH013 to pRH018; Table 1) by using minDBm or minCBm (genomic and GenBank accession numbers BMEII0927 and AAL54169, respectively) and performing Western blot experiments on E. coli DH10B and B. abortus 544 crude extracts with anti-HA, anti-GST, or anti-MYC antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, hybrid proteins MinDBm and MinCBm fused to 3HA, GST, or 13MYC were detected at the expected sizes in crude extracts from E. coli (Fig. 3A) and B. abortus (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Neither MinDBm nor MinCBm cross-reacted with anti-HA, anti-GST, or anti-MYC antibodies since we did not detect any protein bands on crude extracts from E. coli and B. abortus strains expressing minDBm or minCBm from pRH001 or pRH002 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Expression and coexpression of Brucella MinC and MinD fused to tags (3HA, GST, and 13MYC) in E. coli and B. abortus. Western blot experiments were carried out on E. coli DH10B (A and C) and B. abortus 544 (B) crude extracts with anti-HA (α-HA) (Eurogentec), anti-GST (Sigma), and anti-MYC (Eurogentec) sera at a dilution of 1/1,000. Arrows indicate GST protein translated from its own ATG. The Gateway cassette in frame with 3HA cloned into pRH016 is in the same frame than the lacZ′ present in the pBBR1-MCS1 backbone, therefore allowing translation of a hybrid protein such as MinD-3HA from two different ATGs, which gave rise to two protein products of different sizes (indicated by arrowheads). The shills represent the corresponding parental empty plasmid, the RK2oriV-based low-copy-number plasmid pMR10cat for pRH013 to pRH015, and pBBR1-MCS1 for pRH016 to pRH018. For the coexpression experiment (C), the anti-GST serum was first used, directly followed by incubation with the anti-MYC serum.

Moreover, we were also able to detect two different hybrid proteins (i.e., MinCBm-GST and MinDBm-13MYC) in a crude extract prepared from E. coli DH10B carrying two compatible clones, pRH017-minCBm-GST and pRH015-minCBm-13MYC (Fig. 3C). Similar experiments were performed with E. coli cells coproducing MinCBm-3HA from pRH013 and MinCBm-GST from pRH017 (data not shown).

These results validated the use of pRH013 to pRH018 for expression or coexpression of tagged protein-coding ORFs, which will be useful for detecting physical interaction by coaffinity or coimmunopurification of protein complexes.

Integrative reporter vectors.

The last group of destination vectors described here, pRH007 to pRH012, pRH019, and pRH020 (Table 1), are made for monitoring gene expression. Indeed, they are designed to fuse an ORF to the coding sequence (CDS) for a fluorescent protein (CFP, YFP, or EGFP) or to the CDS for a tag (3HA, GST or 13MYC) but differ from vectors described in previous sections (pRH004 to pRH006 and pRH013 to pRH018) by the absence of a promoter region. Since these vectors are replicative only in members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, they are expected, in all other bacteria, to integrate into the genome at the locus where the ORF is located by homologous recombination, therefore duplicating the target ORF. This would result in the fusion between endogenous promoter, CDS, and the fused tag, allowing the monitoring of gene expression through fluorescence or quantification of tag abundance. pRH007 to pRH012 destination vectors may also be used to determine the localization of the corresponding proteins expressed from the endogenous promoter since after LR reactions ORFs are in frame with the fluorescent reporter genes. In this way, vectors pRH010 to pRH012 were successfully used for determining the subcellular distribution of several proteins involved in cell division and differentiation of B. abortus (R. Hallez, unpublished results).

In conclusion, we designed 20 Gateway destination vectors divided into three groups for functional analyses of complete or partial bacterial ORFeomes. These vectors open the way to genome-wide investigations such as localizome, i.e., the subcellular localization of all predicted proteins of a given bacterium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to A. Dricot, J. Mignolet, and R.-M. Genicot for generous technical assistance during cloning procedures. We thank M. Vidal, D. Hill, and J.-F. Rual for helpful and stimulating discussions and L. Van Melderen and B. Nkengfac for comments on the manuscript. We also thank the “Unité Interfacultaire de Microscopie Electronique” of the University of Namur for providing a scanning electron microscopy facility.

This work was supported by Fonds de la Recherche Fondamentale Collective (convention 2.4521.04) and by an “Action de Recherche Concertée” (ARC 04/09-325, Communauté Française de Belgique). At the time of this study, Régis Hallez held a Ph.D. fellowship from the Fonds pour la formation à la Recherche dans l'Industrie et dans l'Agriculture.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 December 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoine, R., and C. Locht. 1992. Isolation and molecular characterization of a novel broad-host-range plasmid from Bordetella bronchiseptica with sequence similarities to plasmids from gram-positive organisms. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1785-1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellefontaine, A. F., C. E. Pierreux, P. Mertens, J. Vandenhaute, J. J. Letesson, and X. De Bolle. 2002. Plasticity of a transcriptional regulation network among alpha-proteobacteria is supported by the identification of CtrA targets in Brucella abortus. Mol. Microbiol. 43:945-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasch, M. A., J. L. Hartley, and M. Vidal. 2004. ORFeome cloning and systems biology: standardized mass production of the parts from the parts-list. Genome Res. 14:2001-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer, P. A., R. E. Crossley, and L. I. Rothfield. 1989. A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E. coli. Cell 56:641-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dozot, M., R. A. Boigegrain, R. M. Delrue, R. Hallez, S. Ouahrani-Bettache, I. Danese, J. J. Letesson, X. De Bolle, and S. Kohler. 2006. The stringent response mediator Rsh is required for Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis virulence, and for expression of the type IV secretion system virB. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1791-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dricot, A., J. F. Rual, P. Lamesch, N. Bertin, D. Dupuy, T. Hao, C. Lambert, R. Hallez, J. M. Delroisse, J. Vandenhaute, I. Lopez-Goni, I. Moriyon, J. M. Garcia-Lobo, F. J. Sangari, A. P. Macmillan, S. J. Cutler, A. M. Whatmore, S. Bozak, R. Sequerra, L. Doucette-Stamm, M. Vidal, D. E. Hill, J. J. Letesson, and X. De Bolle. 2004. Generation of the Brucella melitensis ORFeome version 1.1. Genome Res. 14:2201-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haine, V., A. Sinon, F. Van Steen, S. Rousseau, M. Dozot, P. Lestrate, C. Lambert, J. J. Letesson, and X. De Bolle. 2005. Systematic targeted mutagenesis of Brucella melitensis 16M reveals a major role for GntR regulators in the control of virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:5578-5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartley, J. L., G. F. Temple, and M. A. Brasch. 2000. DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination. Genome Res. 10:1788-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs, C., I. J. Domian, J. R. Maddock, and L. Shapiro. 1999. Cell cycle-dependent polar localization of an essential bacterial histidine kinase that controls DNA replication and cell division. Cell 97:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs-Wagner, C. 2004. Regulatory proteins with a sense of direction: cell cycle signalling network in Caulobacter. Mol. Microbiol. 51:7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen, R. B., and L. Shapiro. 2000. Proteins on the move: dynamic protein localization in prokaryotes. Trends Cell Biol. 10:483-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar, A., S. Agarwal, J. A. Heyman, S. Matson, M. Heidtman, S. Piccirillo, L. Umansky, A. Drawid, R. Jansen, Y. Liu, K. H. Cheung, P. Miller, M. Gerstein, G. S. Roeder, and M. Snyder. 2002. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev. 16:707-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labaer, J., Q. Qiu, A. Anumanthan, W. Mar, D. Zuo, T. V. Murthy, H. Taycher, A. Halleck, E. Hainsworth, S. Lory, and L. Brizuela. 2004. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 gene collection. Genome Res. 14:2190-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, S., C. M. Armstrong, N. Bertin, H. Ge, S. Milstein, M. Boxem, P. O. Vidalain, J. D. Han, A. Chesneau, T. Hao, D. S. Goldberg, N. Li, M. Martinez, J. F. Rual, P. Lamesch, L. Xu, M. Tewari, S. L. Wong, L. V. Zhang, G. F. Berriz, L. Jacotot, P. Vaglio, J. Reboul, T. Hirozane-Kishikawa, Q. Li, H. W. Gabel, A. Elewa, B. Baumgartner, D. J. Rose, H. Yu, S. Bosak, R. Sequerra, A. Fraser, S. E. Mango, W. M. Saxton, S. Strome, S. Van Den Heuvel, F. Piano, J. Vandenhaute, C. Sardet, M. Gerstein, L. Doucette-Stamm, K. C. Gunsalus, J. W. Harper, M. E. Cusick, F. P. Roth, D. E. Hill, and M. Vidal. 2004. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science 303:540-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marston, A. L., H. B. Thomaides, D. H. Edwards, M. E. Sharpe, and J. Errington. 1998. Polar localization of the MinD protein of Bacillus subtilis and its role in selection of the mid-cell division site. Genes Dev. 12:3419-3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raskin, D. M., and P. A. de Boer. 1999. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4971-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder, B. K., B. L. House, M. W. Mortimer, S. N. Yurgel, S. C. Maloney, K. L. Ward, and M. L. Kahn. 2005. Development of a functional genomics platform for Sinorhizobium meliloti: construction of an ORFeome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5858-5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro, L., H. H. McAdams, and R. Losick. 2002. Generating and exploiting polarity in bacteria. Science 298:1942-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih, Y. L., T. Le, and L. Rothfield. 2003. Division site selection in Escherichia coli involves dynamic redistribution of Min proteins within coiled structures that extend between the two cell poles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7865-7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Driessche, B., L. Tafforeau, P. Hentges, A. M. Carr, and J. Vandenhaute. 2005. Additional vectors for PCR-based gene tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe using nourseothricin resistance. Yeast 22:1061-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Mullem, V., M. Wery, X. De Bolle, and J. Vandenhaute. 2003. Construction of a set of Saccharomyces cerevisiae vectors designed for recombinational cloning. Yeast 20:739-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walhout, A. J., G. F. Temple, M. A. Brasch, J. L. Hartley, M. A. Lorson, S. van den Heuvel, and M. Vidal. 2000. GATEWAY recombinational cloning: application to the cloning of large numbers of open reading frames or ORFeomes. Methods Enzymol. 328:575-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.