Abstract

Influences of infaunal burrows constructed by the polychaete (Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus) on O2 concentrations and community structures and abundances of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) in intertidal sediments were analyzed by the combined use of a 16S rRNA gene-based molecular approach and microelectrodes. The microelectrode measurements performed in an experimental system developed in an aquarium showed direct evidence of O2 transport down to a depth of 350 mm of the sediment through a burrow. The 16S rRNA gene-cloning analysis revealed that the betaproteobacterial AOB communities in the sediment surface and the burrow walls were dominated by Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143-like sequences, and most of the clones in Nitrospira-like NOB clone libraries of the sediment surface and the burrow walls were related to the Nitrospira marina lineage. Furthermore, we investigated vertical distributions of AOB and NOB in the infaunal burrow walls and the bulk sediments by real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) assay. The AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in the burrow walls were comparable with those in the sediment surfaces. These numbers in the burrow wall at a depth of 50 to 55 mm from the surface were, however, higher than those in the bulk sediment at the same depth. The microelectrode measurements showed higher NH4+ consumption activity at the burrow wall than those at the surrounding sediment. This result was consistent with the results of microcosm experiments showing that the consumption rates of NH4+ and total inorganic nitrogen increased with increasing infaunal density in the sediment. These results clearly demonstrated that the infaunal burrows stimulated O2 transport into the sediment in which otherwise reducing conditions prevailed, resulting in development of high NH4+ consumption capacity. Consequently, the infaunal burrow became an important site for NH4+ consumption in the intertidal sediment.

Benthic infaunal activities, such as burrow formation, burrow irrigation, defecation, and excretion of soluble and insoluble metabolites, increase the surface area across which solutes can diffuse into or out of the sediments and the substrate availability for inhabiting microorganisms (5, 13, 17, 24, 25, 32, 34). These burrows also provide a more stable physical environment compared to bulk sediment. Therefore, the sediment surrounding the infaunal burrows (i.e., burrow walls) could have markedly higher levels of microbial biomass, diversity, and activity compared with the bulk sediment. Previous studies have revealed that benthic infaunal activities resulted in changes in biogeochemical characteristics and microbial community structures in sediments (20, 22, 31). Although many studies demonstrated that the presence of benthic infauna strongly affects the microbial ecology of estuarine sediments, surprisingly little attention has been paid to bioturbation effects on nitrification. In estuarine systems with high inputs of nitrogenous compounds, sediment is a major site for nitrification due to abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and their high activities (1). One such estuarine is the Niida River estuary in Hachinohe City, Japan, where the water quality deterioration (e.g., presence of organic carbon and NH4+) is evident, mainly due to the discharge of treated and untreated domestic and industrial wastewater and urban and agricultural runoff (26, 27).

The solute concentrations in an infaunal burrow have been measured by collecting the liquid samples in a burrow (17). This method was not completely satisfying, because the concentration measured was the mean value throughout the burrow. Application of microelectrodes has enabled direct measurements of O2 and nutrients in burrows without sampling. Applications of O2 microelectrodes revealed the presence of O2 in infaunal burrows (5), in the burrows of freshwater insects (34), and in an actively ventilated polychaete burrow (13). NH4+ concentration profiles in freshwater sediments as influenced by insect larvae were also measured by NH4+ microelectrodes (1). These studies have demonstrated evidence of enhanced mass transport through the burrows. However, the measurements were limited in depths of just a few centimeters from the sediment surface due to low accessibility of the microelectrodes and the uncertainty of the exact position of the burrow.

Microbial community structures in infaunal burrows and tubes have been investigated by 16S rRNA gene-cloning analysis (20, 22) and ester-linked phospholipid fatty acid analysis (31). These studies have provided a good understanding of the microbial community structure and diversity in the burrow and sediment and allowed comparison with biogeochemical characteristics. One study revealed that the microbial community structures in burrow walls were different from those in the bulk sediment (31). However, community structure, abundance, and in situ activity of nitrifying bacteria in infaunal burrows and bulk sediment have not been analyzed, compared, and linked to available O2 concentrations in the burrows.

Therefore, we have investigated the influences of infaunal burrows on microbial community structures and the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) and in situ activities of AOB in intertidal sediments by applying 16S rRNA gene-cloning analysis, real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) assay, and microelectrodes. The Niida River estuarine sediment was selected, in which a high number of infaunal burrows were constructed by the benthic infauna Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, which generally inhabited the intertidal zone of the Japanese estuary. To directly measure in situ O2 concentration profiles in the burrows, we have constructed a continuous-flow aquarium with agar slits in a sideboard through which microelectrodes could be inserted into the burrow.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

River water and sediment samples were collected as described below during low tide at an intertidal area of the Niida River, Hachinohe City, Japan, which was located approximately 1.5 km from the river mouth (27). The samples were immediately transferred to the laboratory and were analyzed within 12 h.

Microcosm experiments.

Microcosm experiments were carried out to determine the influence of infaunal density on the consumption rates of NH4+ and total inorganic nitrogen (Ni) that was defined as the sum of the concentrations of NH4+, NO2−, and NO3−. Grab samples of sediments were obtained at the study site and passed through a 1-mm mesh to remove pebbles, large detritus particles, and indigenous infaunas. After thorough mixing, the sediments were apportioned into cylindrical sediment containers (11.4 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height) to give a final sediment height of 30 cm. Various numbers of T. heterochaetus were placed on the sediment surface in each microcosm and allowed to burrow into the sediments. They generally burrowed within a few minutes. The sediment surfaces in the microcosms were covered with 1-mm meshes to prevent the infaunas from moving out of the microcosms. The microcosms were then buried in the sediment at the study site, where the surfaces of the microcosms were aligned with the surface of the natural sediment at the study site. The microcosms were allowed to stabilize for 2 to 3 weeks. Each microcosm was then brought to the laboratory and placed in an aquarium filled with 3 liters of river water collected at the same site. NH4Cl and NaNO3 were added to the river water, resulting in final concentrations of approximately 360 μM of NH4+ and NO3−, respectively. O2 concentration of the overlying water was kept at ca. 210 μM by continuous bubbling with air. The microcosms were incubated for 48 h in the dark. The changes in NH4+, NO2−, and NO3− concentrations in the overlying water were monitored with time. The consumption rates of NH4+ [R(NH4+)] and Ni [R(Ni)] were calculated from the decreases in NH4+ and Ni concentrations during the initial 12-h incubation, respectively. In total, 16 microcosm experiments were conducted with different infaunal densities.

Microelectrode measurements.

The concentration profiles of O2 and NH4+ in the sediment were measured in the laboratory using microelectrodes as described by Nakamura et al. (26). Clark-type microelectrodes for O2 were prepared and calibrated as described by Revsbech (30). The LIX-type microelectrodes for NH4+ were constructed, calibrated, and used according to the protocol described by de Beer et al. (9) and Okabe et al. (28). To directly monitor O2 concentrations inside an infaunal burrow along the depth, we constructed an aquarium with an acrylic plate (20 cm wide, 1 cm thick, and 50 cm high) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). There were 45 slits (0.5 by ∼5 cm), which were filled with a 3% agar plate, in one side of the aquarium (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). By this means, we could determine the burrow structure and microelectrode position in the burrow. The aquarium was filled with the sediment collected in the same way as that for the microcosm experiments. An infauna (T. heterochaetus) was placed on the sediment surface and allowed to burrow. River water was continuously fed to the aquarium at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1. The aquarium was maintained at 20°C in the dark. After 3 days, the infauna created a visible burrow. For the measurements of O2 concentrations inside the infaunal burrow, the O2 microelectrode was inserted into the burrow through the agar plate.

In order to analyze NH4+ consumption rates in the burrow wall, the concentration profiles of O2 and NH4+ were measured at a cross-section of the sediment in the aquarium. A synthetic medium was used to avoid interference with the LIX-type microelectrodes for NH4+ (26). The sediment was incubated in the medium at 20°C for more than 30 min before measurements to ensure that steady-state profiles were obtained. Three concentration profiles were measured for each chemical species and at each measuring point. The details of microelectrode measurements are described elsewhere (26, 27). Based on the O2 and NH4+ concentration profiles measured, the total O2 and NH4+ consumption rates were calculated using Fick's first law of diffusion (26, 27). The molecular diffusion coefficients used for the calculations were 2.09 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 for O2 in liquid, 1.38 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 for NH4+ in liquid (3), and 2.2 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 for O2 in 3% agar plate at 20°C (16). Differences between the rates were statistically analyzed by t test.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification.

Three sediment samples (approximately 1 cm3) were collected with sterile spatulas at different points corresponding to each sampling position (i.e., sediment surface, bulk sediment, and burrow walls at depths of 25 to 30 mm and 50 to 55 mm). DNA was extracted from each sample (approximately 0.2 cm3) using a Fast DNA spin kit (Bio 101; Qbiogene Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. The 16S rRNA gene fragments from the extracted total DNA were amplified with EX Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Ohtsu, Japan) by using the AOB-specific primer set CTO189fA/B, CTO189fC, and CTO654r (18) as well as the Nitrospira-like NOB-specific primer set of Ntspa685 (15) and NTSPAf (26). The PCR conditions used for AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB were described by Hermansson and Lindgren (14) and Nakamura et al. (26). PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel. To reduce the possible bias caused by PCR amplification, the 16S rRNA gene was amplified in triplicate tubes for each sample, and then nine PCR products in total were combined for the next cloning step.

Cloning and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and phylogenetic analysis.

The purified PCR products were ligated into a pCR-XL-TOPO vector and transformed into ONE SHOT Escherichia coli cells following the manufacturer's instructions (TOPO XL PCR cloning; Invitrogen). Partial sequencing of 16S rRNA gene inserts (465 bp for AOB and 510 bp for Nitrospira-like NOB) was performed using an automatic sequencer (ABI Prism 3100 Avant Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems) with a BigDye terminator Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems). All sequences were checked for chimeric artifacts by the CHECK_CHIMERA program in the Ribosomal Database Project (21) and compared with similar sequences of the reference organisms by a BLAST search (2). Sequence data were aligned with the CLUSTAL W package (33). Clones with more than 97% sequence similarity were grouped into the same operational taxonomic unit (OTU), and their representative sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis.

Quantification of AOB and Nitrospira- and Nitrobacter-like NOB by Q-PCR.

Sediment samples were collected from sediment surface, burrow walls, and bulk sediments at depths of 5 to 10 mm, 25 to 30 mm, and 50 to 55 mm as described above. Total cell counts were performed after the diluted sediment samples on 0.2-μm membrane filters were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. At least 15 replicate analyses were performed for each sample. Q-PCR assays were performed to quantify AOB and Nitrospira- and Nitrobacter-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA genes. The Q-PCR assay for betaproteobacterial AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB was performed as described previously (14, 26). The Q-PCR assay for Nitrobacter-like NOB was performed in a total volume of 25 μl with 12.5 μl of SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 7.5 pmol of each of the forward and reverse primers (FGPS872f and FGPS1269r) (10), 2.5 μl of bovine serum albumin solution (Invitrogen), and either 0.1 pg of sample DNA or 10 to 105 copies per well of the standard bacterium DNA of Nitrobacter winogradskyi (NBRC 14297). All Q-PCRs were performed in MicroAmp Optical 96-well reaction plates with an optical cap (PE Applied Biosystems). The template DNA in the reaction mixtures were amplified and monitored with an ABI prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems). The cycling regimen for AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB was as follows: hold for 2 min at 50°C, hold for 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. The cycling regimen for Nitrobacter-like NOB was as follows: hold for 2 min at 50°C, hold for 10 min at 95°C, and 80 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 50°C. The detection limits for AOB, Nitrospira-like NOB, and Nitrobacter-like NOB in this study were 2.7 × 10, 1.6 × 102 and 5.4 × 10 copies per well, respectively, which correspond to 6.7 × 104, 4.0 × 104, and 1.4 × 104 copies cm−3 when the sediment sample volume and DNA extraction step are taken into account. Four replicate analyses were performed for each sample. A t test was applied to evaluate differences of the total bacterial cells and AOB- and Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers among the samples.

Analytical methods.

The NH4+ concentrations were colorimetrically determined (6), and the NO2− and NO3− concentrations were determined using an ion chromatograph (HIC-6A; Shimadzu) equipped with a Shim-pack IC-AI column. The samples for NH4+, NO2−, and NO3− were filtered through 0.2-μm membrane filters before the analysis. The O2 concentration and pH in the overlying water were directly determined using an O2 and a pH electrode, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of representative 35 clones used for the phylogenetic analysis are AB239541, AB239545, AB239546, AB239560, AB239561, AB239566, and AB264558 to AB264586.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sediment characteristics.

Many burrow openings of approximately 5 mm in diameter were found on the sediment surface at the study site during low tide. Three types of benthic infaunas inhabited the sediment. The numerically most abundant species was T. heterochaetus (84%), whereas the densities of Notomastus sp. (11%) and Neanthes japonica (5%) were low. Because the size of a T. heterochaetus organism was much bigger (approximately 5 mm in diameter) than the other two species (<1 mm in diameter), we speculated that all of the visible burrows were created by T. heterochaetus. The visible burrows extended down to a depth of at least 350 mm. Density of benthic infaunas in the upper 350 mm of the sediment was ca. 5,700 individuals m−3. Assuming a burrow of T. heterochaetus to be a straight tube of 5 mm in diameter and 350 mm in length, the specific surface area of the burrow walls in the upper 350 mm of the sediment was calculated to be 26.4 m2 m−3. The burrow walls were covered with thin oxidized light-brown layers. The color of the burrow wall was similar to that of the sediment surface. Average NH4+, NO2−, and NO3− concentrations (±standard deviations) in the overlying water were 44 ± 39 μM, 1 ± 5 μM, and 127 ± 168 μM, respectively (n = 57). During high tide, we occasionally found that suspended particles flew into the burrow and the fluffy biofilm developed at the burrow opening oscillated, indicating the overlying water was introduced into the burrow. In contrast, the water in burrows stood during low tide. Thus, we expected that the local environment in the burrows (i.e., the concentrations of O2, NH4+, NO2−, and NO3−) was dynamically changing with time compared with that in the river water. Further information on the sediment at the study site and the physical and chemical parameters in river water can be found elsewhere (26, 27).

Microcosm experiments.

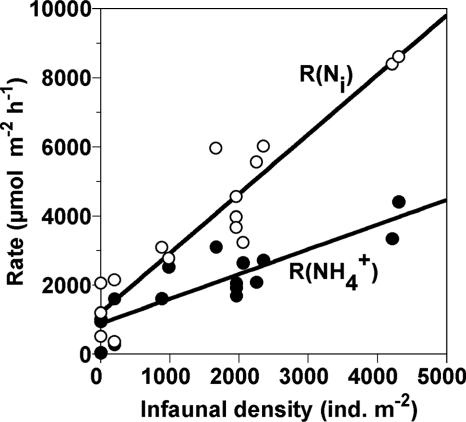

The consumption rates of NH4+ [R(NH4+)] and Ni [R(Ni)] of the sediments with various benthic infaunal densities (i.e., T. heterochaetus) were determined in the microcosm experiments (Fig. 1). Mean values (±standard deviations) of R(NH4+) and R(Ni) of the sediment without the infauna were 670 ± 540 μmol m−2 h−1 and 1,260 ± 770 μmol m−2 h−1, respectively. Both rates increased as infaunal density increased. The increase in R(Ni) was more significant than that of R(NH4+).

FIG. 1.

Consumption rates of NH4+ [R(NH4+)] and total inorganic nitrogen [R(Ni)] of the sediment as a function of the density of T. heterochaetus in the microcosm experiments. The solid lines indicate linear regression of the data. The equations of the straight lines were y = 0.72x + 890 (with r2 = 0.75) (NH4+ consumption) and y = 1.72x + 1,200 (with r2 = 0.88) (total inorganic nitrogen consumption). ind., individuals.

Community structures of AOB and NOB.

Three 16S rRNA gene clone libraries of AOB belonging to the Betaproteobacteria were constructed from three sediment samples taken from the sediment surface (SS) and the burrow walls at depths of 25 to 30 mm (BW-25) and 50 to 55 mm (BW-50) (Table 1; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Sixty-seven, 47, and 52 clones were randomly selected from the SS, BW-25, and BW-50 clone libraries, respectively, and partial sequences of 465 bp were analyzed. In total, the clones were grouped into 27 OTUs, and their representative sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis (data not shown). According to Purkhold et al. (29), we classified the betaproteobacterial AOB into seven stable lineages (Nitrosomonas oligotropha, Nitrosomonas marina, Nitrosomonas cryotoleransa, Nitrosomonas europaea/Nitrosococcus mobilis, Nitrosomonas communis, Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143, and Nitrosospira briensis). In all three samples the most frequently detected clones were affiliated with the Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143 lineage with 93 to 99% sequence similarity (Table 1). These clones represented 30, 62, and 44% of the total clones recovered from the SS, BW-25, and BW-50 samples, respectively. Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143-like sequences have been found at intermediate salinity sites of other estuaries (4, 12). The second most frequently detected clones recovered from the SS and BW-25 samples were affiliated with the Nitrosomonas marina lineage (detection frequency of 9 and 19%, respectively), whereas the second frequently detected clones were affiliated with the Nitrosospira briensis lineage (detection frequency of 17%) in the BW-50 samples. Nitrosomonas marina-like sequences have also been detected in relatively high-salinity environments (7, 12), because the N. marina lineage comprises obligate halophilic and salt-tolerant species. Thus, the AOB community structures in the burrow walls were similar to that in the sediment surface. This reflected the transport of overlying water into the burrows as confirmed by the microelectrode measurements. In this study, we focused only on the community structure of aerobic AOB affiliated with the betaproteobacteria, whereas other ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (e.g., anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria, the genus Nitrosococcus affiliated with the gammaproteobacteria, and ammonia-oxidizing Crenarchaea) have not been analyzed. Contributions of these AOB to NH4+ oxidation in the sediment should be examined in a future study.

TABLE 1.

Detection frequency and phylogenetic relatives of the AOB clones analyzed at sediment surface (SS) and burrow walls (BW) at 25 to 30 mm and 50 to 55 mm from the sediment surface

| Lineage and closest relative | No. of OTUs (no. of clones) in the following layer

|

Similarity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | BW-25 | BW-50 | ||

| Nitrosomonas oligotropha lineage | ||||

| Nitrosomonas sp. strain Is79A3 (AJ621026) | 1 (2) | 95-98 | ||

| Unidentified Betaproteobacterium Vm4 (AJ003756) | 1 (2) | 99 | ||

| Nitrosomonas marina lineage | ||||

| Nitrosomonas sp. strain Is343 (AJ621032) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 97-99 |

| Uncultured bacterium clone AZP2-9 (AY186223) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 95-98 |

| Nitrosomonas europaea/Nitrosococcus mobilis lineage | ||||

| Nitrosomonas europaea (BX321856) | 1 (1) | 99 | ||

| Nitrosomonas communis lineage | ||||

| Nitrosomonas communis (AJ298732) | 1 (2) | 95 | ||

| Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143 lineage | ||||

| Uncultured AOB clone B8s180r (AB212150) | 1 (18) | 1 (27) | 1 (12) | 95-99 |

| Nitrosomonas sp. strain Nm143 (AY123794) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 94-96 | |

| Nitrosomonas sp. strain NS20 (AB212171) | 2 (2) | 1 (4) | 93-98 | |

| Nitrosospira briensis lineage | ||||

| Nitrosospira multiformis (AY123807) | 2 (2) | 3 (9) | 94-97 | |

| Total | 8 (67) | 7 (47) | 12 (52) | |

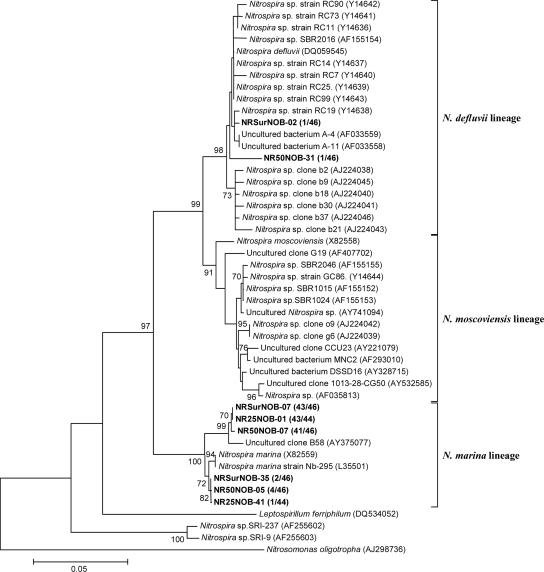

In contrast to the AOB community structure, information about community structure and abundance of NOB in intertidal sediments is scarce. Although Nitrobacter is the most commonly isolated and studied NOB from water environments, recent studies demonstrated the presence of Nitrospira as dominant NOB in sediments (1, 7, 12, 26). In this study, the Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were one to three orders of magnitude higher than those of the Nitrobacter-like NOB (Table 2). Hence, the community structures of Nitrospira-like NOB in the sediment were further analyzed. Three 16S rRNA gene clone libraries of Nitrospira-like NOB were constructed from the SS, BW-25, and BW-50 samples (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Partial sequences of 510 bp were analyzed from 46, 44, and 46 clones randomly selected from the SS, BW-25, and BW-50 clone libraries, respectively. The diversity of the Nitrospira-like NOB clone libraries was very low, and more than 97% of the clones analyzed were related to the Nitrospira marina lineage, with 96 to 99% sequence similarity. Other clones were related to the Nitrospira defluvii lineage, with 97 to 99% sequence similarity (data not shown). Thus, the Nitrospira-like NOB community structures in the burrow walls were also similar to that in the sediment surface. Similarly, presence of Nitrospira marina-like NOB in estuarine sediment was indicated by stable isotope probing analysis (12). Nitrospira marina-like NOB were also detected in a submerged filter treating high-salinity industrial wastewater containing NH4+ and phenol (8) and in biofilms developed in freshwater or seawater aquaria (15).

TABLE 2.

Summary of total microbial cell counts and 16S rRNA gene copy numbers of AOB and Nitrospira- and Nitrobacter-like NOB in the bulk sediment and burrow wall samplesa

| Sediment depth (mm) | Total no. of cells (109 cells cm−3)

|

AOB (107 copies cm−3)

|

Nitrospira (107 copies cm−3)

|

Nitrobacter (107 copies cm−3)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sediment | Burrow | Sediment | Burrow | Sediment | Burrow | Sediment | Burrow | |

| 0-5 mm (surface) | 6.5 ± 0.7 | NDb | 2.4 ± 0.3 | NDb | 2.8 ± 1.8 | NDb | 0.1 ± 0.0 | NDb |

| 5-10 mm | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 5.7 ± 4.1 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| 25-30 mm | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 50-55 mm | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

The values are averages ± standard deviations.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for Nitrospira-like NOB, showing the positions of the clones obtained from three different points in the sediment. The tree was generated by using 510 bp of the 16S rRNA genes and the neighbor-joining method. Scale bar, 5% sequence divergence. Parsimony bootstrap values of 70 or greater are presented at the nodes (from 100 replicates). The N. oligotropha sequence (AJ298736) served as the outgroup for rooting the tree. The numbers in parentheses indicate the frequencies of appearance of identical clones in the total clones analyzed. The first and second numbers/designations after “NR” indicate the sampling depth and the clone designation. For example, NRSurNOB-02 is the Nitrospira-like NOB clone number 02 detected from the surface of the Niida River sediment.

Microbial density.

Total microbial cell counts were performed on different layers of the bulk sediment and the burrow wall samples (Table 2). The lateral average of total bacterial cell numbers was highest (6.5 × 109 cells cm−3) at the sediment surface and slightly decreased with depth down to 4.0 × 109 cells cm−3 at a depth of 50 to 55 mm of the sediment. The cell numbers in the burrow wall were lower (1.0 × 109 to 1.9 × 109 cells cm−3) than those of the bulk sediment samples (P < 0.0001; n = 15), probably because the burrow walls were composed of loosely packed sediment (biofilms).

Betaproteobacterial AOB and Nitrospira- and Nitrobacter-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were quantified by Q-PCR assay (Table 2). The AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were in the range of 107 copies cm−3, except for those at a depth of 50 to 55 mm of the bulk sediment. The presence of aerobic AOB in anoxic parts of the sediment could be explained by direct transport of AOB from the sediment surface by mixing, persistence of AOB, and capability of anoxic respiration of AOB. In contrast, the Nitrobacter-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were one to three orders of magnitude lower than the Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers. Thus, Nitrospira-like NOB might be the numerically dominant NOB in the intertidal sediment. The AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in the burrow walls (1.2 × 107 to 4.2 × 107 and 1.0 × 107 to 3.3 × 107 gene copies cm−3 for AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB, respectively) were comparable to those at the sediment surface (2.4 × 107 and 2.8 × 107 gene copies cm−3 for AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB, respectively) (P > 0.05; n = 4). These copy numbers slightly increased with depth in the burrow wall, whereas in the bulk sediment these copy numbers decreased with depth. Therefore, the AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB-specific 16S rRNA gene copy numbers became higher in the burrow wall than in the bulk sediment at a depth of 50 to 55 mm (P < 0.01; n = 4).

Microelectrode measurements.

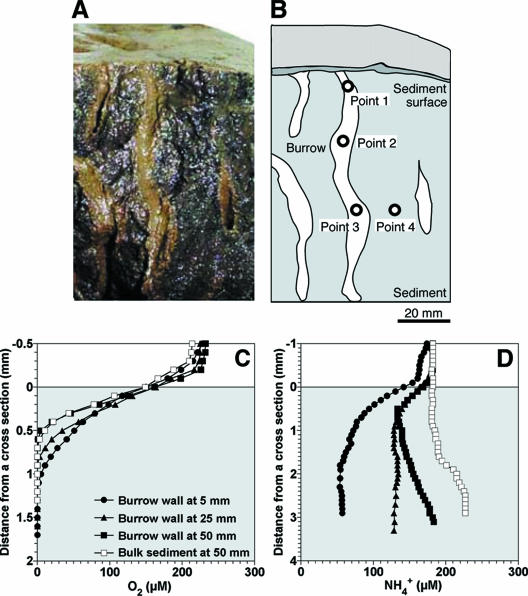

The concentration profiles of O2 and NH4+ were measured at a cross-section of the sediment (Fig. 3A). The microelectrodes were inserted into four points on the cross-section: the burrow wall at depths of 5 mm (point 1), 25 mm (point 2), and 50 mm (point 3) and the bulk sediment at a depth of 50 mm (point 4), as indicated in Fig. 3B. O2 penetration depths were in the range of 0.6 to 1.2 mm at the cross-section of the sediment (Fig. 3C). The total O2 consumption rates at the points 1, 2, 3 (i.e., in the burrow wall), and 4 (i.e., in the bulk sediment) were calculated to be 0.19, 0.21, 0.26, and 0.23 μmol cm−2 h−1, respectively. Moreover, the O2 concentrations at the sediment surface and bulk sediments at 5 mm and 25 mm were measured (data not shown), and the total O2 consumption rates were calculated to be 0.20, 0.23, and 0.21 μmol cm−2 h−1, respectively. NH4+ was consumed in the upper parts of the sediment at the points 1, 2, and 3, indicating high NH4+ consumption activity at the burrow wall (Fig. 3D). The total NH4+ consumption rates at the points 1, 2, and 3 were calculated to be 0.050, 0.026, and 0.033 μmol cm−2 h−1, respectively. The total NH4+ consumption rates at the sediment surface and in the bulk sediment at a depth of 50 mm were 0.028 and 0.003 μmol cm−2 h−1, respectively. Although O2 consumption rates in the burrow wall were similar to those in the sediment surface (P > 0.05), the total NH4+ consumption rate at point 1 was higher than that at the sediment surface (P < 0.05), and the rates at points 2 and 3 were comparable to that at the sediment surface. NH4+ was produced in the deeper part of sediments at points 3 and 4.

FIG. 3.

Concentration profiles of O2 and NH4+ at a cross-section of the sediment. (A) Photograph of the cross-section of the sediment. (B) A drawing of the cross-section of the sediment indicated in panel A. Points 1 to 4 indicate the points where the microelectrodes were inserted. (C and D) Concentration profiles of O2 and NH4+ measured at each point, respectively. The profiles are average values (n = 3) and the standard deviations were less than 10% of the average values. Zero on the horizontal axis corresponds to the surface of the cross-section. The legends of panel D are the same as those in panel C.

Microelectrode measurements as well as Q-PCR assay demonstrated that the 16S rRNA gene copy numbers of AOB and Nitrospira-like NOB and the NH4+ consumption rates in the burrow walls were comparable with or higher than those in the sediment surface and in the bulk sediment (especially at a depth of 50 to 55 mm). These results indicate that infaunal burrows supported greater abundance of nitrifying bacteria and in situ NH4+ consumption activity in the burrow wall. These results were also consistent with the result of the microcosm experiments showing that increasing benthic infaunal density in the sediment resulted in the increases in NH4+ and total inorganic nitrogen consumption rates (Fig. 1). Mayer et al. showed that nitrification potentials in tube or burrow walls of six types of benthic macrofaunas were significantly greater than those of the surrounding bulk sediments (23). Furthermore, Dollhopf et al. found that coupled nitrification-denitrification was enhanced by macrofaunal burrowing activity in salt marsh sediments (11).

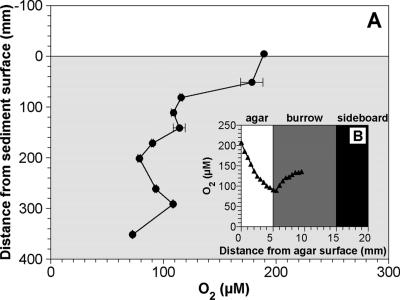

Many studies have aimed to measure solute concentrations in burrows (5, 13, 24, 25, 32, 34). However, all of the data were limited in the upper parts (a few centimeters of depth) of the sediments. In this study, we constructed and used the aquarium with agar slits in a sideboard to overcome this limitation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The O2 microelectrode was inserted into the center of the burrow at different depths through the agar slits, and an O2 concentration profile along the burrow structure was determined (Fig. 4A). A typical horizontal O2 concentration profile is depicted in Fig. 4B. The O2 concentration in the burrow decreased from 190 μM in the overlying water to 120 μM at a depth of 80 mm, below which the decrease in the O2 concentration was moderate (Fig. 4A). Thus, approximately 70 μM of O2 still existed even at a depth of 350 mm. In contrast, O2 penetration depth was less than 1 mm only below the sediment surface without infaunal burrows (data not shown). This was probably attributed to the infaunal irrigation activity to exchange the water with low concentrations of O2 and nutrients with fresh water (19).

FIG. 4.

(A) Vertical O2 concentration profile along an infaunal burrow, measured in the aquarium with slits filled with agar plates in a sideboard. (B) Data points were obtained from the horizontal O2 concentration profiles at different depths. The values indicate the average O2 concentrations at the center of the burrow (i.e., 10 mm from agar surface). The error bars indicate the standard deviations of the measurements for 10 min at each position. (B) A typical horizontal O2 concentration profile in an infaunal burrow. An O2 microelectrode was inserted into the center of a burrow through the agar plate. Zero millimeters, 5 mm, and 10 mm on the horizontal axis correspond to the agar surface, the agar-burrow interface, and the center of the burrow, respectively.

The advantages of this method were to be able to know the exact position of burrows in sediment and to directly measure the concentration profiles in the burrows in the deeper parts of the sediment. However, O2 diffused into the burrow and sediment through the agar plate, as indicated by the O2 concentration gradients in the agar plate (Fig. 4B). The O2 transport rates through the agar plate were, therefore, calculated from the O2 concentration gradients in the agar plate based on Fick's first law of diffusion. The diffusion coefficient for O2 in the 3% agar used for the calculation was 2.2 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 (16). The mean O2 transport rate was calculated to be 0.012 ± 0.001 μmol cm−2 h−1. This value corresponded to ca. 5% of the total O2 consumption rates in the burrow walls (0.19 to 0.26 μmol cm−2 h−1). Thus, O2 concentrations in the burrow would be slightly overestimated in this study. However, this does not negate the general trend in the results presented here.

In summary, combination of the 16S rRNA gene-based molecular approach and microelectrode measurements clearly demonstrated that the infaunal burrow facilitated O2 transport into the sediment, which supported the greater abundance and in situ activity of nitrifying bacteria in the burrow walls in the intertidal sediment. Further studies with more quantitative techniques, such as fluorescent in situ hybridization and microelectrodes for N2O, NO2−, and NO3−, are desired to fully understand nitrogen cycling in the bioturbated sediment.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant-in-aid (13650593) for developmental scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan. Y.N. was supported by a research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altmann, D., P. Stief, R. Amann, and D. de Beer. 2004. Nitrification in freshwater sediments as influenced by insect larvae: quantification by microsensors and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Microb. Ecol. 48:145-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrussow, L. 1969. Diffusion, p. 513-727. In H. Borchers, H. Hauser, K. H. Hellwege, K. Schafer, and E. Schmidt (ed.), Landolt-Bornstein Zahlenwerte und Functionen, 6th ed., vol. II/5a. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhard, A. E., T. Donn, A. E. Giblin, and D. A. Stahl. 2005. Loss of diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria correlates with increasing salinity in an estuary system. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1289-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binnerup, S. J., K. Jensen, N. P. Revsbech, M. H. Jensen, and J. Sørensen. 1992. Denitrification, dissimilatory reduction of nitrate to ammonium, and nitrification in a bioturbated estuarine sediment as measured with 15N and microsensor techniques. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:303-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clesceri, L., A. Greenberg, and A. Eaton (ed.). 1998. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Coci, M., D. Riechmann, P. L. E. Bodelier, S. Stefani, G. Zwart, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2005. Effect of salinity on temporal and spatial dynamics of ammonia-oxidising bacteria from intertidal freshwater sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 53:359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortés-Lorenzo, C., M. L. Molina-Muñoz, B. Gómez-Villalba, R. Vilchez, A. Ramos, B. Rodelas, E. Hontoria, and J. González-López. 2006. Analysis of community composition of biofilms in a submerged filter system for the removal of ammonia and phenol from industrial wastewater. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Beer, D., A. Schramm, C. M. Santegoeds, and M. Kühl. 1997. A nitrite microsensor for profiling environmental biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:973-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degrange, V., and R. Bardin. 1995. Detection and counting of Nitrobacter populations in soil by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2093-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dollhopf, S. L., J. H. Hyun, A. C. Smith, H. J. Adams, S. O'Brien, and J. E. Kostka. 2005. Quantification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and factors controlling nitrification in salt marsh sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:240-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freitag, T. E., L. Chang, and J. I. Prosser. 2006. Changes in the community structure and activity of betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing sediment bacteria along a freshwater-marine gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 8:684-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glud, R. N., J. K. Gundersen, H. Røy, and B. B. Jørgensen. 2003. Seasonal dynamics of benthic O2 uptake in a semienclosed bay: importance of diffusion and faunal activity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48:1265-1276. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermansson, A., and P. E. Lindgren. 2001. Quantification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in arable soil by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:972-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hovanec, T. A., L. T. Taylor, A. Blakis, and E. F. Delong. 1998. Nitrospira-like bacteria associated with nitrite oxidation in freshwater aquaria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:258-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulst, A. C., H. J. H. Hens, R. M. Buitelaar, and J. Tramper. 1989. Determination of the effective diffusion coefficient of oxygen in gel materials in relation to gel concentration. Biotechnol. Tech. 3:199-204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koike, I., and H. Mukai. 1983. Oxygen and inorganic nitrogen contents and fluxes in burrows of the shrimps Callianassa japonica and Upogebia major. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 12:185-190. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowalchuk, G. A., J. R. Stephen, W. De Boer, J. I. Prosser, T. M. Embley, and J. W. Woldendorp. 1997. Analysis of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the β subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in coastal sand dunes by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S ribosomal DNA fragments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1489-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristensen, E. 1983. Ventilation and oxygen uptake by three species of Nereis (Annelida: Polychaeta). I. Effects of hypoxia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 12:289-297. [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-García, P., F. Gaill, and D. Moreira. 2002. Wide bacterial diversity associated with tubes of the vent worm Riftia pachyptila. Environ. Microbiol. 4:204-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maidak, B. L., G. L. Olsen, N. Larsen, R. Overbeek, M. J. McCaughey, and C. R. Woese. 1997. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 25:109-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsui, G. Y., D. B. Ringelberg, and C. R. Lovell. 2004. Sulfate-reducing bacteria in tubes constructed by the marine infaunal polychaete Diopatra cuprea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7053-7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer, M. S., L. Schaffner, and W. M. Kemp. 1995. Nitrification potentials of benthic macrofaunal tubes and burrow walls: effects of sediment NH4+ and animal irrigation behavior. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 121:157-169. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyers, M. B., H. Fossing, and E. N. Powell. 1987. Microdistribution of interstitial meiofauna, oxygen and sulfide gradients, and the tubes of macro-infauna. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 35:223-241. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers, M. B., E. N. Powell, and H. Fossing. 1988. Movement of oxybiotic and thiobiotic meiofauna in response to changes in pore-water oxygen and sulfide gradients around macro-infaunal tubes. Mar. Biol. 98:395-414. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura, Y., H. Satoh, T. Kindaichi, and S. Okabe. Community structure, abundance, and in situ activity of nitrifying bacteria in river sediments as determined by the combined use of molecular techniques and microelectrodes. Environ. Sci. Tech. 40:1532-1539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nakamura, Y., H. Satoh, S. Okabe, and Y. Watanabe. 2004. Photosynthesis in sediments determined at high spatial resolution by the use of microelectrodes. Wat. Res. 38:2440-2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okabe, S., H. Satoh, and Y. Watanabe. 1999. In situ analysis of nitrifying biofilms as determined by in situ hybridization and the use of microelectrodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3182-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purkhold, U., M. Wagner, G. Timmermann, A. Pommerening-Röser, and H.-P. Koops. 2003. 16S rRNA and amoA-based phylogeny of 12 novel betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing isolates: extension of the dataset and proposal of a new lineage within the nitrosomonads. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1485-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revsbech, N. P. 1989. An oxygen microelectrode with a guard cathode. Limnol. Oceanogr. 34:474-478. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steward, C. C., S. C. Nold, D. B. Ringelberg, D. C. White, and C. R. Lovell. 1996. Microbial biomass and community structures in the burrows of bromophenol producing and non-producing marine worms and surrounding sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 133:149-165. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stief, P., D. Altmann, D. de Beer, R. Bieg, and A. Kureck. 2004. Microbial activities in the burrow environment of the potamal mayfly Ephoron virgo. Freshw. Biol. 49:1152-1163. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, F., A. Tessier, and L. Hare. 2001. Oxygen measurements in the burrows of freshwater insects. Freshw. Biol. 46:317-327. [Google Scholar]