Abstract

ClpB is a member of the bacterial protein-disaggregating chaperone machinery and belongs to the AAA+ superfamily of ATPases associated with various cellular activities. The mechanism of ClpB-assisted reactivation of strongly aggregated proteins is unknown and the oligomeric state of ClpB has been under discussion. Sedimentation equilibrium and sedimentation velocity show that, under physiological ionic strength in the absence of nucleotides, ClpB from Escherichia coli undergoes reversible self-association that involves protein concentration-dependent populations of monomers, heptamers, and intermediate-size oligomers. Under low ionic strength conditions, a heptamer becomes the predominant form of ClpB. In contrast, ATPγS, a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, as well as ADP stabilize hexameric ClpB. Consistently, electron microscopy reveals that ring-type oligomers of ClpB in the absence of nucleotides are larger than those in the presence of ATPγS. Thus, the binding of nucleotides without hydrolysis of ATP produces a significant change in the self-association equilibria of ClpB: from reactions supporting formation of a heptamer to those supporting a hexamer. Our results show how ClpB and possibly other related AAA+ proteins can translate nucleotide binding into a major structural transformation and help explain why previously published electron micrographs of some AAA+ ATPases detected both six- and sevenfold particle symmetry.

Keywords: ClpB, AAA ATPase, molecular chaperone, protein association, nucleotide binding, analytical ultracentrifugation

Among highly sophisticated protein machines that use energy from ATP to drive macromolecular rearrangements, the AAA+ superfamily has recently attracted the attention of researchers (Neuwald et al. 1999; Lupas and Martin 2002). AAA stands for “ATPases associated with various cellular activities”, which implies that these proteins are involved in a variety of functions, such as protein quality control (refolding, disaggregation, and degradation), membrane fusion and vesicular transport, DNA replication and repair, and cytoskeletal regulation (Vale 2000; Ogura and Wilkinson 2001). AAA+ proteins share specific amino-acid sequence motifs and some biochemical properties. A unifying structural property of AAA+ ATPases is the formation of single oligomeric rings. Whereas most ring-type AAA+ structures show a sixfold symmetry, a few members of this family of ATPases also have been “sighted” as particles with a sevenfold symmetry in electron microscopy image analysis (Rohrwild et al. 1997; Kim et al. 2000; Miyata et al. 2000). The functional significance of different oligomeric assemblies in AAA+ ATPases and the mechanism of conversion between different oligomers in solution have not yet been explored. The nature of couplings between ATP binding/hydrolysis and possible structural changes within the AAA+ rings is also under intense discussion (Wang et al. 2001; Rouiller et al. 2002).

ClpB, a bacterial AAA+ ATPase, is a member of a multichaperone system (with DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE) that reactivates strongly aggregated proteins (Goloubinoff et al. 1999; Motohashi et al. 1999; Zolkiewski 1999). Similar protein-disaggregation machineries have been identified in yeast (Glover and Lindquist 1998) and plants (Queitsch et al. 2000), but the mechanism of ClpB-mediated protein reactivation remains unknown. Unlike many AAA+ proteins that form stable oligomers, ClpB and other closely related Clp ATPases undergo reversible nucleotide-dependent self-association (Parsell et al. 1994; Maurizi et al. 1998; Zolkiewski et al. 1999). The oligomers of ClpA (Kessel et al. 1995), ClpX (Grimaud et al. 1998), HslU (Bochtler et al. 2000), and Hsp104 (Parsell et al. 1994) are hexamers in the presence of ATP. In contrast, the identity of a nucleotide-induced form of ClpB is under discussion. Published reports suggest that ATP induces either a hexameric (Zolkiewski et al. 1999) or a heptameric (Kim et al. 2000) form of ClpB.

To resolve this discrepancy, we investigated the molecular properties of ClpB under a broad range of solution conditions. We tested the hypothesis that self-association reactions of ClpB may involve both a hexamer and a heptamer and that different oligomers can be selectively stabilized by buffer conditions. We characterized the nucleotide-independent and the nucleotide-induced oligomerization of Escherichia coli ClpB in solution. Our results show that the binding of nucleotides switches the ring assembly mechanism of ClpB from one supporting heptamer formation to one preferentially stabilizing hexamers. The nucleotide-driven structural switch in ClpB may provide a mechanism of coupling between ATP binding/hydrolysis and induction of conformational changes in aggregated proteins.

Results

ClpB forms a mixture of oligomers under physiological ionic strength conditions

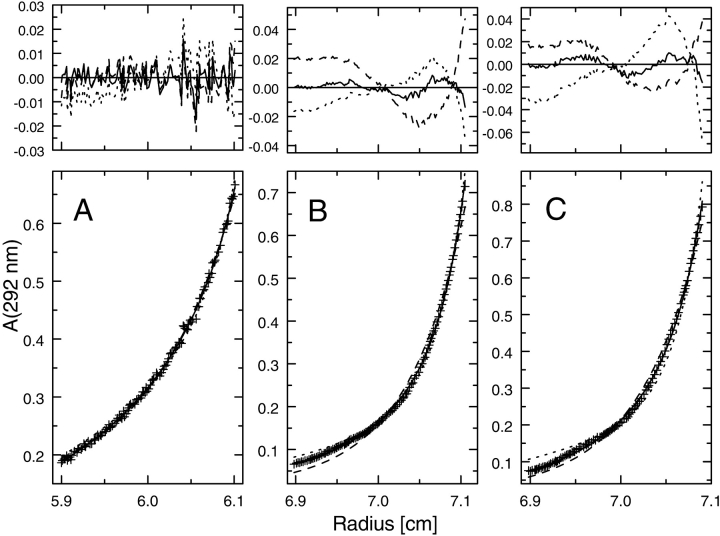

Sedimentation equilibrium data for ClpB in a buffer containing 0.2 M KCl in the absence of nucleotides (Fig. 1 ▶) cannot be approximated by a single-species model. The residuals of a single-species fit of three data sets for ~1–4 mg/mL ClpB (loading concentration) are not random and they strongly exceed the experimental absorbance noise level of <0.01 (see Fig. 1 ▶, upper panels). Similarly, two-species models that assume reversible association of monomers into heptamers (Fig. 1 ▶), hexamers, or other oligomers (not shown) describe the data very poorly. Fits of the equilibrium data improve significantly for three-species association models, such as monomer-dimer-heptamer (Fig. 1 ▶) or monomer-dimer-hexamer (not shown), as demonstrated by the residuals becoming more randomly distributed and their magnitudes becoming comparable with the data accuracy. The accuracy of fits using three-species models including a dimer as the intermediate is significantly better than for those with a trimer, a tetramer, and so forth (data not shown). The monomer-dimer-heptamer and monomer-dimer-hexamer models give fits of similar quality. The analysis of sedimentation equilibrium data cannot rule out a possibility that more than one intermediate-size oligomer is present in solution.

Figure 1.

Sedimentation equilibrium of ClpB at physiological ionic strength. ClpB was dialyzed against 50 mM Hepes/KOH at pH 7.5, 0.2 M KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM EDTA and loaded into a centrifuge cell at 0.96 mg/mL (A), 2.0 mg/mL (B), and 4.0 mg/mL (C). Protein concentration gradients (crosses, lower panels) measured at equilibrium at 8000 rpm (4°C) are shown along with fits corresponding to a single-species model (broken line), monomer-heptamer association (dotted line), and monomer-dimer-heptamer association (solid line). The upper panels show residuals (Aexp-Amodel) for the single-species fit (broken line), monomer-heptamer (dotted line), and monomer-dimer-heptamer (solid line). Three data sets shown in panels A, B, and C were simultaneously included in the fitting of each model. The single-species fit gave an apparent molecular weight of 257,100. In the self-association fits, the monomer molecular weight of ClpB (95,543) has been selected as a known constant and the association equilibrium constants were used as adjustable parameters. The monomer-dimer-heptamer fit gave the following values of the equilibrium constants: monomer-dimer, K12 = 5 × 106 M−1; monomer-heptamer, K17 = 2 × 1037 M−6.

We conclude that ClpB in solution under physiological ionic strength undergoes a protein-concentration dependent self-association that involves more than two different molecular species. This result is consistent with previous studies that showed an increase in the sedimentation coefficient of ClpB at increasing protein concentration (Zolkiewski et al. 1999; Barnett et al. 2000). Monomeric ClpB is in equilibrium with at least two larger oligomers under physiological ionic strength conditions: a high-molecular-weight oligomer (hexamer or heptamer) and an intermediate-size oligomer, most likely a dimer. The remaining part of this work has been devoted to the characterization of the high-molecular-weight oligomers of ClpB under different solution conditions.

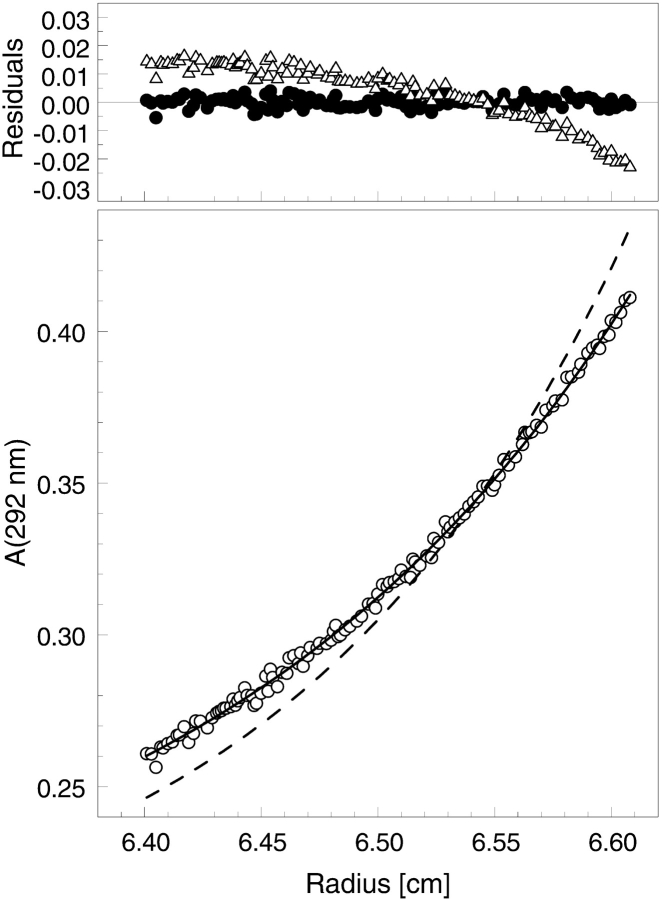

ATP stabilizes hexameric ClpB

In the presence of saturating amounts of a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS, and 0.2 M KCl, the sedimentation equilibrium data for ClpB are consistent with a single molecular species of 531,000 molecular weight (Fig. 2 ▶), which is ~7% lower than the predicted molecular weight of a hexameric ClpB. A simulated protein concentration gradient for heptameric ClpB deviates significantly from the experimental data, as shown by high and nonrandom residuals (see Fig. 2 ▶, upper panel). This result for ClpB is consistent with the hexameric structure found for most AAA+ proteins in the presence of ATP, including other Clp ATPases, and varies from the conclusion of Kim et al. (2000), who suggested a heptameric structure of ATP-bound ClpB.

Figure 2.

Sedimentation equilibrium of ClpB in the presence of an ATP analog. A ClpB sample was collected from a gel filtration column (Superose 6 PC 3.2/30, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech); equilibrated with 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.5, 0.2 M KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM ATPγS; and loaded into a centrifuge cell at 3.0 mg/mL. The protein concentration gradient (circles, lower panel) measured at equilibrium at 3500 rpm (4°C) is shown along with a model fit (solid line) assuming a single component of 531,000 molecular weight. The upper panel shows residuals (Aexp-Amodel) for the single-species fit (solid circles). The simulated concentration gradient for a heptameric ClpB (Mr 668,800) is also shown (broken line, lower panel), along with the corresponding residuals (triangles, upper panel).

Heptameric ClpB predominates in the absence of nucleotides

Because electrostatic interactions stabilize ClpB oligomers (Barnett and Zolkiewski 2002), the association equilibrium of ClpB, as shown in Figure 1 ▶, shifts strongly toward the fully associated species under low ionic strength conditions (Kim et al. 2000). Indeed, the sedimentation equilibrium data for ClpB in the absence of nucleotides in a buffer without KCl are consistent with a single molecular species of 685,000 molecular weight (cf. Figs. 3 ▶, 1 ▶), which is ~2% higher than the predicted molecular weight of heptameric ClpB. In contrast, the simulated protein concentration gradient for hexameric ClpB deviates strongly from the experimental data (cf. Figs. 3 ▶, 2 ▶). We conclude that heptameric ClpB is stabilized by low salt conditions in the absence of nucleotides.

Figure 3.

Sedimentation equilibrium of ClpB at low ionic strength. A ClpB sample was dialyzed against 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM EDTA and loaded into a centrifuge cell at 2.8 mg/mL. The protein concentration gradient (circles, lower panel) measured at equilibrium at 3000 rpm (4°C) is shown along with a model fit (solid line), assuming a single component of 685,000 molecular weight. The upper panel shows residuals (Aexp-Amodel) for the single-species fit (circles). The simulated concentration gradient for a hexameric ClpB (Mr 573,260) is also shown (broken line, lower panel), along with the corresponding residuals (triangles, upper panel).

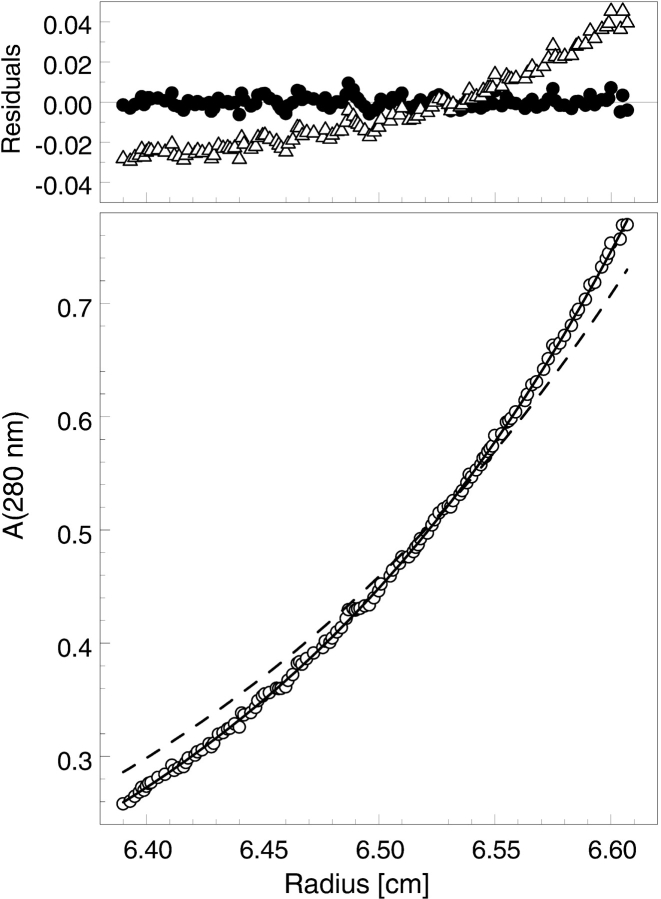

Because the sedimentation equilibrium experiments showed a significant difference in the molecular weight of ClpB in 0.2 M KCl with ATPγS (Fig. 2 ▶) and in a low-salt buffer without nucleotides (Fig. 3 ▶), we also tested the size of oligomers formed under those conditions by using negative-stain electron microscopy. Indeed, the average diameter of end views of the ClpB oligomers formed under physiological ionic strength in the presence of ATPγS (~13 nm, Fig. 4A ▶) is smaller than that of the low-salt oligomers (~16 nm, Fig. 4B ▶). Similarly, the apparent central cavity of the ring formed in the presence of ATPγS (~1.5 nm, Fig. 4A ▶) is smaller than that of the ring formed in the low-salt buffer (~2.5 nm, Fig. 4B ▶). These size differences are consistent with the larger apparent molecular weight of the low-salt form of ClpB (see Figs. 2 ▶, 3 ▶), and with the presence of an additional subunit in the oligomer.

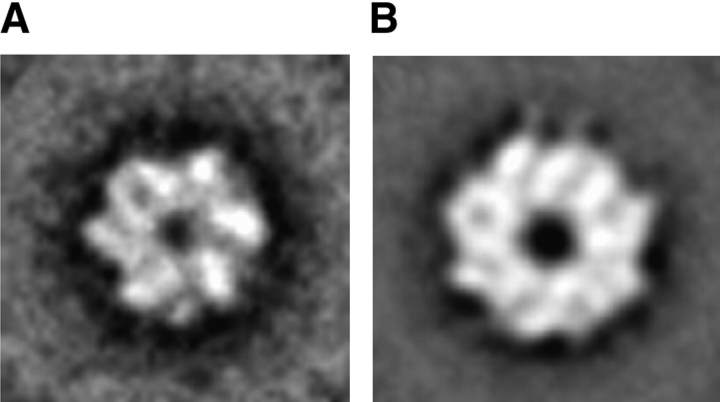

Figure 4.

Electron microscopy images of ClpB. (A) Averaged electron micrographs of ClpB in the presence of ATPγS. The ClpB sample prepared as in Figure 2 ▶ was diluted to ~0.1 mg/mL and stained with uranyl acetate. Eighty-one end views of ClpB oligomers were aligned and averaged. (B) Averaged electron micrographs of ClpB at low ionic strength. The ClpB sample prepared as in Figure 3 ▶ was diluted to ~0.1 mg/mL and stained with uranyl acetate. The average includes 298 end views of ClpB oligomers. The size of the image frame in panels A and B is 25 nm.

Translational and rotational alignment and averaging of end views observed in electron micrographs of ClpB with ATPγS (Fig. 4A ▶) indicate the sixfold particle symmetry. In contrast, the symmetry of low-salt oligomers is not apparent (Fig. 4B ▶) due to a more uniform distribution of the protein density along the edge of the oligomeric ring. Nevertheless, the molecular weight of these particles measured by sedimentation equilibrium indicates a heptameric structure, which is in agreement with the sevenfold symmetry of selected eigen-images of ClpB reported by Kim et al. (2000).

Collectively, our results reveal that ClpB is capable of forming two types of ring-like oligomers: hexamers and heptamers. Which one of these oligomers equilibrates with monomeric ClpB under physiological ionic strength conditions in the absence of nucleotides? As discussed earlier (see Fig. 1 ▶), sedimentation equilibrium cannot unequivocally resolve the molecular weight of the high-molecular-weight oligomer. In order to observe the associated ClpB particles in electron micrographs, a highly concentrated protein sample in 0.2 M KCl must be prepared, which precludes resolved image analysis. Thus, to determine whether it is hexameric or heptameric ClpB that equilibrates with smaller oligomers in the 0.2-M KCl buffer, we performed sedimentation velocity experiments at high protein concentration (Figs. 5 ▶, 6 ▶).

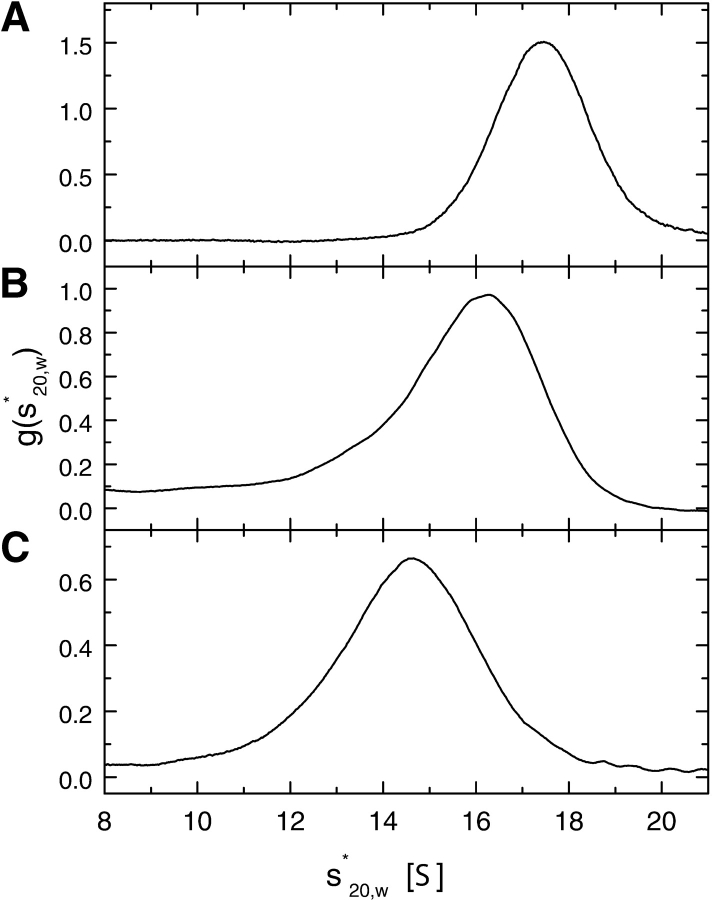

Figure 5.

Sedimentation velocity of ClpB at 20°C and 40,000 rpm. Representative results of the time-derivative analysis (Stafford III 1992) are shown for 2 mg/mL ClpB in the low-salt buffer (A), the buffer containing 0.2 M KCl (B), and with 0.2 M KCl and 2 mM ATPγS (C). Solid lines show apparent distribution functions g(s*20,w) vs. the sedimentation coefficient s*20,w in Svedberg units (S).

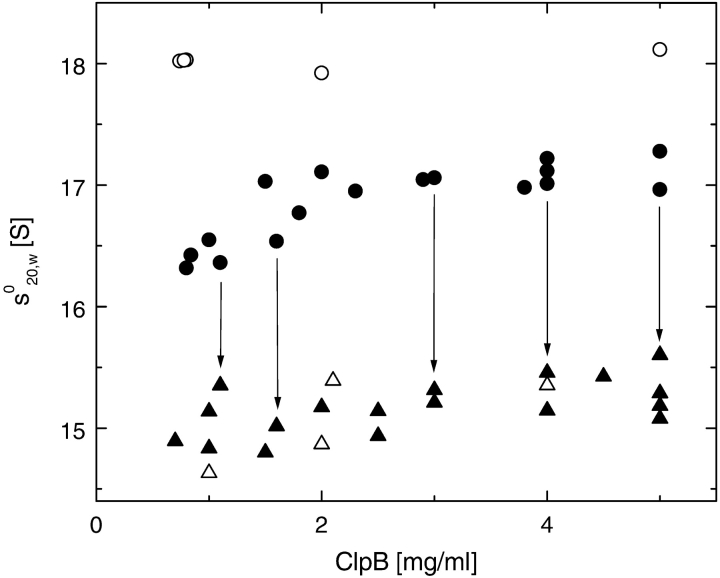

Figure 6.

Apparent sedimentation coefficients of ClpB. Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed at 20°C and 40,000 rpm for ClpB samples prepared in the low-salt buffer (open circles), the buffer containing 0.2 M KCl (filled circles), with 0.2 M KCl and 2 mM ATPγS (filled triangles), or 2 mM ADP (open triangles) at a given protein concentration. In each experiment, the value of s°20,w was obtained from the maximum of the g(s*20,w) distribution (see Fig. 5 ▶). In several experiments, s°20,w was determined first in the absence of nucleotides and then again after restoring uniform protein concentration in the centrifuge cell and adding ATPγS (arrows).

At 0.1–0.2 mg/mL in 0.2 M KCl, ClpB sediments as a predominant molecular species with the sedimentation coefficient s°20,w ~ 4 S (Zolkiewski et al. 1999; Barnett et al. 2000). At ~0.5–1 mg/mL, a strong heterogeneity of sedimenting species of ClpB is observed (Zolkiewski et al. 1999), in agreement with a monomer-oligomer equilibrium for ClpB (see Fig. 1 ▶). Above ~1 mg/mL, a fast-sedimenting species of ClpB is predominant, which indicates a high population of the fully assembled oligomer (Zolkiewski et al. 1999; Barnett et al. 2000).

Figure 5 ▶ shows apparent distributions of the sedimentation coefficient, g(s*20,w) for 2 mg/mL ClpB obtained from the time-derivative analysis of the sedimentation velocity data (Stafford III 1992). For a single molecular component, the g(s*20,w) distribution is symmetrical and its maximum defines the sedimentation coefficient of that molecular species. Thus, the maximum of g(s*20,w) gives the value of s°20,w for the ClpB heptamer (at low ionic strength, Fig. 5A ▶) and the ClpB hexamer (with ATPγS in 0.2 M KCl, Fig. 5C ▶) because a single molecular component predominates in both of these samples (see Figs. 2 ▶, 3 ▶). It has been shown, however, that for mixtures of rapidly equilibrating associating oligomers, the maxima of g(s*20,w) do not correspond to sedimentation coefficients of any of the species, but reflect the population-weighted average of hydrodynamic properties of all interacting components (Stafford III 1994). Thus, the apparent s°20,w obtained from the maximum of the asymmetrical g(s*20,w) for ClpB in 0.2 M KCl (Fig. 4B ▶) does not correspond to the sedimentation coefficient of a specific single oligomeric species because several types of oligomers are in equilibrium under physiological salt conditions (see Fig. 1 ▶).

As shown in Figure 6 ▶, the apparent sedimentation coefficient (s°20,w) of heptameric ClpB (in the low-salt buffer) is ~3 S higher than that for hexameric ClpB (with ATPγS in 0.2 M KCl). Interestingly, the s°20,w values measured for ClpB with ADP agree with those obtained with ATPγS, which indicates that either nucleotide stabilizes hexameric ClpB. In 0.2 M KCl without nucleotides, the s°20,w value for ClpB increases with increasing protein concentration, which indicates the progress of the association reactions. The s°20,w of ClpB in 0.2 M KCl without nucleotides exceeds the values for hexameric ClpB by ~2 S at 2–5 mg/mL protein.

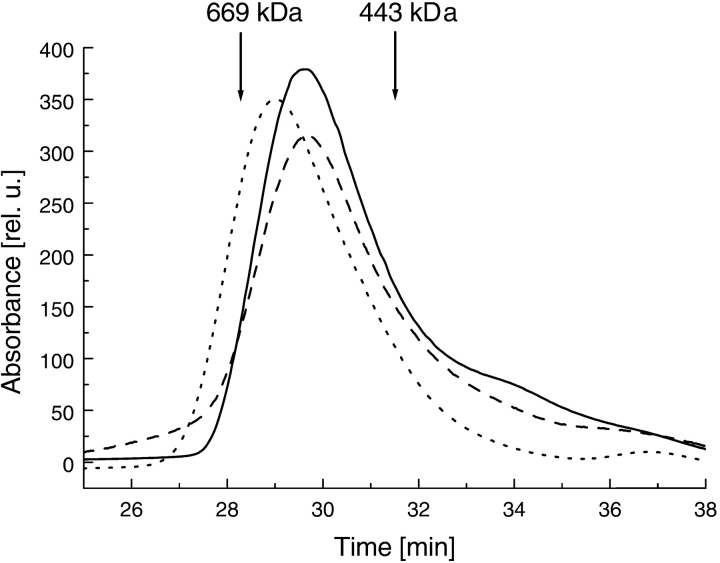

At low protein concentration (<~0.5 mg/mL), gel filtration studies showed an increase in apparent size of ClpB and other Clp ATPases on nucleotide binding (Parsell et al. 1994; Singh and Maurizi 1994; Zolkiewski et al. 1999; Kim et al. 2000), consistent with the nucleotide-induced association of monomers into hexamers. Remarkably, the s°20,w values of ClpB at high protein concentration decrease after adding ATPγS (Fig. 6 ▶, arrows). A decrease of sedimentation coefficient on the addition of a ligand to a macromolecule can be due to decreasing molecular weight (dissociation of an oligomer) or increasing frictional coefficient, which reflects an increase in the particle’s Stokes radius, RS (van Holde et al. 1998). To account for the decrease in s°20,w, such that s°20,w(−ATPγS) / s°20,w(+ATPγS) ≈ 1.14 (see Fig. 6 ▶) without a change in the particle molecular weight, one would predict RS(+ATPγS) / RS(−ATPγS) = 1.14. A similar difference in RS occurs between two gel-filtration standard proteins: thyroglobulin (Mr 669,000) and ferritin (Mr 443,000). However, gel-filtration chromatography of ClpB at ~2 mg/mL (Fig. 7 ▶) shows that RS of ClpB does not increase in the presence of ATPγS. We conclude that it is a decrease in the molecular weight of ClpB that contributes to the significant decrease of s°20,w on the binding of nucleotides (see Fig. 6 ▶). Thus, the association reactions of ClpB under physiological ionic strength in the absence of nucleotides involve an oligomer heavier than a hexamer, which converts to the hexamer in the presence of either ATPγS or ADP. Consequently, the most likely association mechanism that is consistent with both sedimentation equilibrium (see Fig. 1 ▶) and sedimentation velocity (see Fig. 6 ▶) involves ClpB monomers equilibrating with heptamers and dimers in 0.2 M KCl in the absence of nucleotides.

Figure 7.

Gel filtration chromatography of ClpB. ClpB samples were injected onto a Superose 6 column equilibrated with the low-salt buffer (dotted line), with 0.2 M KCl (solid line), or with 0.2 M KCl and 2 mM ATPγS (broken line). The ClpB concentration on the column was ~2 mg/mL. The elution times of thyroglobulin (669 kD) and ferritin (443 kD) are indicated.

If ClpB associates into heptamers in the absence of nucleotides, it can be predicted that s°20,w should approach the value of ~18 S at very high protein concentration (Stafford III 1994), where sedimentation experiments are not feasible due to high sample viscosity. As shown in Figure 6 ▶, s°20,w ≈ 17 S at 5 mg/mL ClpB in 0.2 M KCl, which indicates that the ClpB self-association is not complete at this protein concentration. Indeed, the values of the monomer-dimer-heptamer equilibrium constants (see the legend to Fig. 1 ▶) indicate that the ClpB solution at 5 mg/mL contains ~60% heptamers, ~30% dimers, and ~10% monomers.

Discussion

Taken together, our results suggest a model for oligomerization of ClpB in solution. Sedimentation equilibrium indicates that the formation of heptameric ClpB involves a monomer as well as an intermediate-size oligomer, most likely a dimer (see Fig. 1 ▶). Because the nucleotide binding sites in AAA+ ATPases are located at the interfaces between subunits in an oligomeric ring (Ogura and Wilkinson 2001), monomeric ClpB binds nucleotides with a very low affinity (Barnett et al. 2000). However, oligomers of ClpB are capable of binding nucleotides. We propose that the binding of either ATP or ADP to a nucleotide binding site in the heptamer or other intermediate-size oligomer induces a conformational change at the interface between subunits of a ClpB oligomer. As a result, the contact interfaces of a nucleotide-bound pair of ClpB subunits may become incompatible with those of a nucleotide-free monomer, which inhibits the formation of odd-numbered oligomers, such as a heptamer, and only favors hexamer formation. In effect, the nucleotide binding shifts the association reactions toward hexameric ClpB. Conversely, the release of nucleotides may shift the reactions back toward the monomer-dimer-heptamer association.

Whereas some AAA+ proteins form stable oligomers irrespective of nucleotide binding, in many members of the superfamily, including Clp ATPases as well as the microtubule-disassembling katanin (Hartman and Vale 1999), oligomers undergo nucleotide-dependent association/dissociation reactions. We have performed the first complete characterization of such association equilibrium for an AAA+ protein in solution. Our results suggest that the nucleotide-independent and the nucleotide-dependent behavior of AAA+ oligomers may be more dynamic and may involve more oligomeric species than previously thought. It is remarkable that ClpB forms either stable ring-like hexamers or heptamers, depending on conditions (cf. Figs. 2 ▶, 3 ▶). Interestingly, Hsp104 (Schirmer et al. 2001) and ClpB (Mogk et al. 2003), after cross-linking with glutaraldehyde in the absence of nucleotides, migrated on SDS-PAGE with a slightly higher apparent molecular weight than proteins cross-linked in the presence of ATP. Because of possible cross-linking artifacts and a low resolution of the gels, the apparent molecular-weight differences have not been explored further. In contrast, this study provides an absolute measurement of the molecular weight of ClpB oligomers in solution using sedimentation equilibrium (see Figs. 2 ▶, 3 ▶). Our results are also consistent with those of Rohrwild et al. (1997), who “spotted” both hexamers and heptamers in the population of HslU oligomers. Another AAA+ ATPase that uses a similar self-association mechanism as ClpB is the RuvB branch migration motor, which apparently switches from a heptameric to a hexameric ring on binding to DNA (Miyata et al. 2000).

Our results raise the possibility that ClpB, which is produced in high amounts in bacteria under heat shock (Squires et al. 1991) and whose concentration in vivo is expected to be high, may switch between heptameric and hexameric forms during the cycle of ATP binding/hydrolysis and the release of ADP. The switch between ClpB oligomers involves partial dissociation of the rings, which may provide a mechanism for “prying apart” aggregated substrates, the first step in ClpB-assisted protein reactivation.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The T7 RNA polymerase gene was introduced into a clpB-null strain of E. coli (MC1000ΔclpB::Kmr, a gift from Dr. C. L. Squires, Tufts University; Squires et al. 1991) by infection with λDE3 lysogen (Novagen). The full-length, 95-kD Escherichia coli ClpB was overexpressed in this strain by using the plasmid pET-20b and purified as described previously (Barnett et al. 2000).

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments

A Beckman Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge with a four-position AN-Ti rotor was used in sedimentation experiments. ClpB solutions (0.11 mL) and dialysate buffer (0.12 mL) were placed in a six-channel centrifuge cell. The samples were equilibrated at 4°C at a desired speed and the approach to equilibrium was monitored by repetitive absorption scans every 4 h. After the final data collection (usually after 56–60 h), the rotor was accelerated to 40,000 rpm for ~6 h. Subsequently, the centrifuge was returned to the equilibrium speed and the cells were scanned immediately to obtain the baseline absorption value. The data were analyzed by using the software supplied with the instrument (Beckman). Partial specific volume of ClpB (0.7306 mL/g at 4°C) and the density of buffers were calculated using Sednterp software (ftp://ftp.rasmb.bbri.org/rasmb/). During the analysis of absorption gradients, the data offset was treated as an adjustable parameter and the analysis was accepted only if the offset value agreed with the measured absorption baseline within an experimental error (±0.005).

Sedimentation velocity experiments

ClpB and dialysate buffer (~0.4 mL) were loaded into a double-sector centrifuge cell. After equilibration at 20°C and 3000 rpm, the rotor was accelerated to 40,000 rpm and radial scans of the cell were performed at 1-min intervals using the interference detection system. Apparent sedimentation coefficient distributions were calculated using the time-derivative method (Stafford III 1992) and DCDT+ software (http://www.jphilo.mailway.com/). Observed sedimentation coefficients were corrected to values corresponding to the density and viscosity of water in the limit of a dilute protein solution (s°20,w) using Sednterp software.

Electron microscopy

ClpB preparations were negatively stained with uranyl acetate and recorded using minimal dose methods at a magnification of 60Kx with a JEOL 1200 EXII electron microscope. Digitized micrographs were displayed on a computer monitor and individual images of symmetrical particles with a central dot of stain were selected as “end” views. These images represented only a small fraction of those contained in each micrograph, due either to predominance of alternative orientations, or to distortions caused by the specimen preparation. All end-view images were selected, aligned, and averaged with the SPIDER image analysis software suite, using a reference-independent procedure (Penczek et al. 1992).

Gel filtration chromatography

ClpB samples (10 μL of ~20 mg/mL protein) were chromatographed on a Superose 6 PC 3.2/30 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using a Shimadzu HPLC system with a flow-rate of 0.05 mL/min. Protein standards were obtained from Sigma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM58626) and by the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station (contribution 03–349-J).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

ATPγS

adenosine 5′-O-thiotriphosphate

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03422604.

References

- Barnett, M.E. and Zolkiewski, M. 2002. Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved charged amino acid residues in ClpB from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 41 11277–11283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.E., Zolkiewska, A., and Zolkiewski, M. 2000. Structure and activity of ClpB from Escherichia coli. Role of the amino- and -carboxyl-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 275 37565–37571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochtler, M., Hartmann, C., Song, H.K., Bourenkov, G.P., Bartunik, H.D., and Huber, R. 2000. The structures of HsIU and the ATP-dependent protease HsIU-HsIV. Nature 403 800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover, J.R. and Lindquist, S. 1998. Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40: A novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell 94 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloubinoff, P., Mogk, A., Zvi, A.P., Tomoyasu, T., and Bukau, B. 1999. Sequential mechanism of solubilization and refolding of stable protein aggregates by a bichaperone network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 13732–13737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaud, R., Kessel, M., Beuron, F., Steven, A.C., and Maurizi, M.R. 1998. Enzymatic and structural similarities between the Escherichia coli ATP-dependent proteases, ClpXP and ClpAP. J. Biol. Chem. 273 12476–12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, J.J. and Vale, R.D. 1999. Microtubule disassembly by ATP-dependent oligomerization of the AAA enzyme katanin. Science 286 782–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel, M., Maurizi, M.R., Kim, B., Kocsis, E., Trus, B.L., Singh, S.K., and Steven, A.C. 1995. Homology in structural organization between E. coli ClpAP protease and the eukaryotic 26 S proteasome. J. Mol. Biol. 250 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.I., Cheong, G.W., Park, S.C., Ha, J.S., Woo, K.M., Choi, S.J., and Chung, C.H. 2000. Heptameric ring structure of the heat-shock protein ClpB, a protein-activated ATPase in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 303 655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A.N. and Martin, J. 2002. AAA proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 746–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi, M.R., Singh, S.K., Thompson, M.W., Kessel, M., and Ginsburg, A. 1998. Molecular properties of ClpAP protease of Escherichia coli: ATP-dependent association of ClpA and ClpP. Biochemistry 37 7778–7786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, T., Yamada, K., Iwasaki, H., Shinagawa, H., Morikawa, K., and Mayanagi, K. 2000. Two different oligomeric states of the RuvB branch migration motor protein as revealed by electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 131 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk, A., Schlieker, C., Strub, C., Rist, W., Weibezahn, J., and Bukau, B. 2003. Roles of individual domains and conserved motifs of the AAA+ chaperone ClpB in oligomerization, ATP hydrolysis, and chaperone activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278 17615–17624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi, K., Watanabe, Y., Yohda, M., and Yoshida, M. 1999. Heat-inactivated proteins are rescued by the DnaK.J-GrpE set and ClpB chaperones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 7184–7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald, A.F., Aravind, L., Spouge, J.L., and Koonin, E.V. 1999. AAA+: A class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 9 27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, T. and Wilkinson, A.J. 2001. AAA+ superfamily ATPases: Common structure—diverse function. Genes Cells 6 575–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell, D.A., Kowal, A.S., and Lindquist, S. 1994. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp104 protein. Purification and characterization of ATP-induced structural changes. J. Biol. Chem. 269 4480–4487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penczek, P., Radermacher, M., and Frank, J. 1992. Three-dimensional reconstruction of single particles embedded in ice. Ultramicroscopy 40 33–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queitsch, C., Hong, S.W., Vierling, E., and Lindquist, S. 2000. Heat shock protein 101 plays a crucial role in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12 479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrwild, M., Pfeifer, G., Santarius, U., Muller, S.A., Huang, H.C., Engel, A., Baumeister, W., and Goldberg, A.L. 1997. The ATP-dependent HslVU protease from Escherichia coli is a four-ring structure resembling the proteasome. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller, I., DeLaBarre, B., May, A.P., Weis, W.I., Brunger, A.T., Milligan, R.A., and Wilson-Kubalek, E.M. 2002. Conformational changes of the multifunction p97 AAA ATPase during its ATPase cycle. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer, E.C., Ware, D.M., Queitsch, C., Kowal, A.S., and Lindquist, S.L. 2001. Subunit interactions influence the biochemical and biological properties of Hsp104. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 914–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K. and Maurizi, M.R. 1994. Mutational analysis demonstrates different functional roles for the two ATP-binding sites in ClpAP protease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269 29537–29545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires, C.L., Pedersen, S., Ross, B.M., and Squires, C. 1991. ClpB is the Escherichia coli heat shock protein F84.1. J. Bacteriol. 173 4254–4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford III, W.F. 1992. Boundary analysis in sedimentation transport experiments: A procedure for obtaining sedimentation coefficient distributions using the time derivative of the concentration profile. Anal. Biochem. 203 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994. Sedimentation boundary analysis of interacting systems: Use of the apparent sedimentation coefficient distribution function. In Modern analytical ultracentrifugation (eds. T.M. Schuster and T.M. Laue), pp. 119–137. Birkhauser, Boston.

- Vale, R.D. 2000. AAA proteins. Lords of the ring. J. Cell Biol. 150 F13–F19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holde, K.E., Johnson, W.C., and Ho, P.S. 1998. Principles of physical biochemistry. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Wang, J., Song, J.J., Seong, I.S., Franklin, M.C., Kamtekar, S., Eom, S.H., and Chung, C.H. 2001. Nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in a protease-associated ATPase HsIU. Structure (Camb.) 9 1107–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkiewski, M. 1999. ClpB cooperates with DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE in suppressing protein aggregation. A novel multi-chaperone system from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274 28083–28086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkiewski, M., Kessel, M., Ginsburg, A., and Maurizi, M.R. 1999. Nucleotide-dependent oligomerization of ClpB from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 8 1899–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]