Abstract

This study examined socioeconomic change, social institutions, and serious property crime in transitional Russia. Durkheim’s anomie theory and recent research on violence in Russia led us to expect an association between negative socioeconomic change and property crime. Based upon institutional anomie theory, we also tested the hypothesis that the association between change and crime is conditioned by the strength of non-economic social institutions. Using crime data from the Russian Ministry of the Interior and an index of socioeconomic change, we used OLS regression to estimate cross-sectional models using the Russian regions (n=78) as the unit of analysis. Results surprisingly showed no effect of socioeconomic change on two different measures of robbery, only very limited support for the hypothesis of direct effects of social institutions on crime, and obviously no support for the hypothesis that institutions moderate the effect of change on crime. We interpret these findings in the context of transitional Russia and conclude that rigorous research in other nations is important in determining the generalizability of criminological theories developed to explain crime in Western nations.

This study examined the association between socioeconomic change and serious property crime in Russia and tested the hypothesis that the strength of non-economic social institutions will condition this association. Russia experienced paradigmatic political, social, and economic change in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The country and its citizens are experiencing uncertainty and instability as old social norms and values are being questioned and widely replaced by a new political-economy. These rapid changes have created anomic conditions that in turn may be contributing to a wide array of social problems (Durkheim, 1897), including increased rates of crime and violence (Pridemore, 2003a).

Russia is the largest nation in the world and the nature and the pace of these changes, as well as the strength of social institutions, varies tremendously throughout the country. Recent research leads us to expect crime rates to covary with these factors (Kim, 2003; Pridemore, 2002). We might further expect that the strength of social institutions such as family, education, and polity to play a moderating role in any association between social change and crime. We thus draw upon Messner and Rosenfeld's (1997a) institutional anomie theory to test the idea that even if negative socioeconomic change proves to be associated with crime, the association should be lower than expected in regions where social institutions are stronger (Bernburg, 2002; Chamlin and Cochran, 1995).

Background

Socioeconomic change and its effects

Although Russia launched political and economic reforms in the early 1990s to convert the centrally-planned command economy to a free market, the legal, regulatory, and social institutions necessary for a properly functioning market economy were and continue to be underdeveloped (Goldman, 1996; Hanson, 1998; Intriligator, 1994). Durkheim (1897) argued that during periods of rapid social change norms become unclear and society’s hold over individuals is weakened. This normative confusion is expected to result in increased crime and delinquency as aspirations become less limited, especially during a transition from a totalitarian and communist society to a freer democratic system with a capitalist economy.

Since the collapse of the command economy and the transition toward a free market began in the early 1990s, Russians have experience continued instability. The unemployment rate of 10.5% in 2000 was twice as high as in 1992, nearly 30% of the population is now living in poverty, and Russia’s gross domestic product decreased by almost 40%, industry output was halved, and salaries decreased 45–65% (Gokhberg, Kovaleva, Mindeli, and Nekipelova, 2000). The negative conditions vary widely by region, however, and a sharp cross-sectional divergence in living standards has developed since the reforms were introduced, depending largely upon the type of industry in a region. (Sagers, 1992).

The transition also had an enormous impact on Russian demographic trends such as fertility, mortality, and migration, which are often indicators of anomic social conditions. For example, the concurrent trends in transitional Russia of declining birth rates and rising death rates have led to a shrinking population. Life expectancy of both males and females peaked in 1987 and then for males declined sharply to around 60 years (Heleniak, 1995). The largest increases in death rates were among middle-aged males, who proved to be the most vulnerable to the increased stress brought on by rapid socioeconomic change, an uncertain future, and the collapse of the former Soviet social safety net (Shkolnikov and Meslé, 1996). Offending and victimization rates also indicate that this same age group has the highest rates of homicide and suicide (Pridemore, 2003a; Pridemore and Spivak, 2003). Further, the forces of migration have led to wide regional variation in population age, labor force, social services, and local fiscal systems. A region’s age-sex structure is partially dependent upon the type and number of jobs available, and in turn will have an impact on the supply and demand for schools, health care, the regional tax base, and pension funding (Heleniak, 1997). The demographic shocks to fertility, mortality, and migration have had a major impact on the variation of population and socioeconomic characteristics throughout Russia, which may be associated with the increase in and cross-sectional variation of crime rates in the country.

Property crime

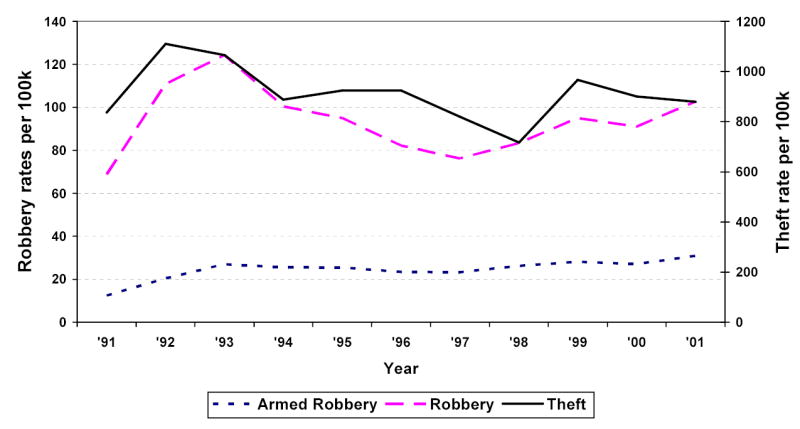

The late 1980s and the transition years of the 1990s produced dramatic increases in Russian crime rates. Data from the Russian Ministry of the Interior show that property crime rose steeply, though not as much as homicide (Kim, 2003; Pridemore, 2003a). Figure 1 shows rates of theft, robbery, and armed robbery in Russia from 1991 to 2001. Property crimes increased in the early 1990s, peaking around 1992 and 1993. After these steep increases, property crime rates were relatively stable until they began to increase again in 1998. The 2001 armed robbery rate was 2.5 times higher than a decade earlier and the 2001 robbery rate was 1.5 times higher. Most importantly for our study, both robbery rates vary widely throughout the nation. Armed robbery and robbery rates range from a low of 7 and 12 per 100,000 in Dagestan to 56 and 214 per 100,000 in Perm Oblast. Anomie and institutional anomie theories lead us to suspect that the differential impact of change, together with the varying strength of social institutions, is partially responsible for this regional variation.

Figure 1.

Property crime rates in Russia, 1991–2001.

Note. The Soviet government did not provide detailed and complete property crime data prior to 1991. Theft is not employed as a dependent variable in this paper but is shown here for descriptive and comparative purposes.

Socioeconomic change and institutional anomie

Institutions are patterned and mutually shared ways societies develop to live together (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, and Tipton, 1991). These templates include the norms, values, statuses, roles, and organizations that define and regulate human conduct. Institutions are thus at the center of social life since they act as guides to how we conduct our affairs, direct our actions into socially acceptable behavior, and increase predictability (LaFree, 1998). Durkheim (1897) argued that rapid social change creates anomie, which can lead to numerous negative consequences for these institutions and for society, including deviance and crime. This occurs because rapid change may weaken social control, which is one of main roles of social institutions such as the family, education, and polity. When social controls are weak or absent, anomic conditions and criminogenic pressures to commit crime become more manifest. In Russia and Eastern Europe, recent empirical work suggests that the social stress and disorganization of the transition to a free market are related to changes in suicide, homicide, and overall mortality (Gavrilova, Semyonova, Evdokushkina, and Gavrilov, 2000; Leon and Shkolnikov, 1998; Pridemore and Spivak, 2003). Yet social disorganization and social capital theories discuss the important role of social institutions in moderating negative structural effects. For example, Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997) show that even in depressed neighborhoods, strong social institutions can act to reduce crime.

Messner and Rosenfeld (1997a) described how capitalist culture may promote intense pressure for economic success at the expense of pro-social non-economic institutions such as family, education, polity, and religion. If the social structure comes to be dominated by the economy it will weaken more socially oriented institutions that might otherwise serve to control behavior and thus reduce crime. According to Messner and Rosenfeld, at the cultural level a dominant capitalist culture stimulates criminal motivations because it stresses economic success without at the same time providing clear regulations about how to achieve it. At the structural level, the dominance of the economy in the institutional balance of power results in weak social control because as the role of economy increases, the role of other institutions decreases, thereby diminishing their pro-social influence. As Russia transitions to a free market, it is likely that its citizens have begun to adopt a capitalist ideology and an emphasis on economic success (Barkan, 1997). However, most Russians do not have legitimate means to achieve material success because of widespread unemployment and poverty. As a result, they may be experiencing the frustration that arises from the discrepancy between these new cultural goals and (1) the system’s failure to provide the means to attain them (Merton, 1938, 1968) and (2) the disconnect between these new goals and the recently discarded ones. Given the central role of the economy in a transition from communism to capitalism, one may expect social institutions like family and polity to lose their salience.

Only a handful of studies have tested institutional anomie theory. First, according to Chamlin and Cochran (1995), Messner and Rosenfeld’s (1997a) institutional anomie theory implies that economic deprivation will be less salient as a predictor of serious crime in the presence of strong non-economic institutions. Therefore, they hypothesized that the association between poverty and property crime is conditioned by the strength of religious, political, and family institutions. Consistent with this hypothesis, their analysis of U.S. states revealed that greater church membership, lower divorce rate, and higher voter turnout significantly reduced the effect of poverty on property crime. Second, Piquero and Piquero (1998) also tested institutional anomie theory with cross-sectional data from the U. S., employing several different operationalizations of institutional strength and using both property and violent crime as dependent variables. Their findings were mixed depending on the measures of social institutions, and the authors concluded that the inferences drawn about institutional anomie theory may depend upon how institutional variables are operationalized. Finally, Savolainen (2000) hypothesized that the positive effect of economic inequality on violence are stronger in nations where the economy dominates the institutional balance of power. This implies a negative interaction effect between economic stratification and the strength of non-economic institutions, which is what is shown by his results. Savolainen concluded that nations that protect their citizens from market forces appear to be immune to the effects of economic inequality on homicide (see also Messner and Rosenfeld, 1997b). Though not necessarily constructed as such, Bernburg (2002) argues that institutional anomie theory is congruent with the study of socioeconomic change and crime and deviance. Durkehim (1897), Polanyi (2001), and Messner and Rosenfeld (1997a) share the notion that radical socioeconomic change likely generates social problems because of a disembedded market economy. According to Bernburg (2002), since the relative strength of social institutions may condition the impact of negative economic conditions on crime, it may also decrease the effects of negative socioeconomic change on crime. Pridemore (2002) and Kim (2003) have shown that poverty and negative socioeconomic change, respectively, are associated with homicide rates in Russia. This discussion of the theoretical and empirical literature thus led us to test the following hypotheses:

Negative socioeconomic change is positively associated with the regional variation of property crime rates in Russia.

The strength of non-economic social institutions is negatively associated with the regional variation of property crime rates in Russia.

The strength of non-economic social institutions condition the effect of negative socioeconomic change on the variation of regional property crime rates in Russia.

Data and methodology

This was a cross-sectional study of Russian regions using 2000 data. The unit of analysis was the administrative region. These regions are analogous to states or provinces, so a lower level of aggregation might be preferred, though we note that the few previous tests of institutional anomie theory have been carried out at the state-(Chamlin and Cochran, 1995; Piquero and Piquero, 1998) and national-levels (Messner and Rosenfeld, 1997b; Savolainen, 2000). There are 89 regions, but data from the contiguous Ingush and Chechen Republics are unreliable and data from nine of the smaller regions (known as autonomous districts) are covered by the larger regions in which they are embedded. We thus had 78 cases for analysis.

Dependent variables

Table 1 provides brief descriptions of all variables. The regional rates per 100,000 residents of robbery (grabezh) and armed robbery (razboi) were used as dependent variables. While robbery is considered a violent crime, its violent aspect is a means to an end that is pecuniary in nature, and in tests of institutional anomie it has been employed as a dependent variable denoting both violent (Piquero and Piquero, 1998) and property crime (Chamlin and Cochran, 1995). Robbery is defined in Section 161 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation as the open theft of property (distinguishable from theft, which is defined in Section 158 as "secret" stealing of property); armed robbery is defined in Section 162 as "an attack on a person in order to steal his/her property, connected with violence dangerous to the life or health of the person or threat of such violence." These data were based on crimes reported to the police and were obtained from the Russian Ministry of the Interior (2001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (n=78).

| Variables | Description | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armed Robbery | Armed robbery rate per 100,000 residents | 25.64 | 10.10 |

| Robbery | Robbery rate per 100,000 residents | 89.58 | 43.98 |

| SE Change | Index of socioeconomic change (Δ population + Δ poverty + Δ unemployment + privatization + foreign capital investment) | 1.38 | 1.13 |

| Family | Proportion of households with only 1 parent and at least 1 child < 18 years old (reverse coded) | −0.16 | 0.02 |

| Education | Rate per 1,000 people enrolled in college | 26.96 | 13.81 |

| Polity | Proportion of registered voters who voted in 2000 Presidential election | 0.69 | 0.05 |

| Inequality | Ratio of the income of the top 20% of population to the income of bottom 20% of population | 6.00 | 2.78 |

| Alcohol | Deaths per 100,000 population due to alcohol poisoning | 28.73 | 17.52 |

| Urban | Proportion of population living in cities > 100,000 residents | 0.39 | 0.17 |

| Males | Proportion of population that is male and aged 25–44 years | 0.15 | 0.01 |

Independent variables: Socioeconomic change and social institutions

We created a composite index to account for regional variation in socioeconomic change. The variables used to measure the index represent multiple dimensions of change (e.g., legal, population, economic) and should not be considered different measures of a single underlying concept. As described below, the measures were coded to highlighted regions that experienced the worst effects of change. The measures included population change, unemployment change, poverty change, privatization, and foreign investment and were obtained from Goskomstat (various years). Population change and the proportion of the active labor force unemployed were measured as residual change scores when 2000 values were regressed on 1992 values. Poverty was measured as the residual change score when 1999 poverty rates (2000 data unavailable) were regressed on 1994 rates (earlier data unavailable). For example, for unemployment the equation was ΔUnemployment = Unemployment2000 − (α + β * Unemployment1992). Residual change scores are superior to raw change scores since they are independent of initial values (Bohrnstedt, 1969). Since all regions were used to estimate the regression, the residual scores also took into account changes in the entire system under study (Morenoff and Sampson, 1997).

The Soviet economic system was characterized by state ownership, so two other indicators of change are privatization and foreign investment. The former was measured as the percentage of the labor force employed in private companies and the latter as foreign capital investment per capita. In essence, these are change scores since both were virtually zero until the adoption of the “Basic Provision for the Privatization of State and Municipal Enterprises in the Russian Federation” in 1992 (Chubais and Vishnevskaya, 1993). Foreign capital investment is an important indicator not simply of worthwhile investment potential but of political and economic stability and of the presence of the relatively strong legal framework required for business.

To create our index of negative socioeconomic change, we coded privatization, foreign investment, and population change1 as 1 if they were more than 0.5 standard deviations below the mean (i.e., the region was substantially worse off than other regions on these measures), 0 otherwise, and coded unemployment and poverty as 1 if they were more than 0.5 standard deviations above the mean (i.e., the region had substantially larger increases in poverty and unemployment relative to other regions), 0 otherwise. These scores were summed, providing a value of 0–5 (with 5 being the worst) for each region. In one respect, this construction of our index means we lose information since we turn interval variables into dummies and thus restrict their variance. Creating a factor or constructing an index by summing z-scores, however, might not allow us to capture the different components of socioeconomic change in a way we wish.

We measured the strength of social institutions as follows. Family was measured as the proportion of all households with a single parent and at least one child under the age of 18, which was reverse coded in order to interpret it in terms of family strength. Although data on this variable will soon be available from the 2002 Russian census, at the moment the most recent data are from the 1994 micro-census. Educational strength was measured as the rate per 1,000 people enrolled in college, which was also obtained from Goskomstat (2001). Voter turnout or the proportion voting for a specific party is often used as a measure of trust or anomie (Chamlin and Cochran, 1995; Villarreal, 2002), so we measured polity as the proportion of registered voters who voted in the 2000 Russian Presidential election. The voting data were obtained from Orttung (2000).

Control variables

Based on the social structure and homicide literature, we employed several controls. First, economic inequality was measured as the ratio of the income received by the top 20% of wage earners to that of the bottom 20% (Goskomstat, 2001). Second, recent research has shown a significant positive association between regional levels of alcohol consumption and violence in Russia (Andrienko, 2001). For reasons explained at length elsewhere (Pridemore, 2002; Shkolnikov, McKee, and Leon, 2001; Shkolnikov and Meslé, 1996), we used the rate of deaths due to alcohol poisoning as a proxy for heavy consumption (Russian Ministry of Health, 2001). Third, we included a measure of the proportion of the population living in cities with at least 100,000 residents (Goskomstat, 2001). Next, although offender data on robbery are unavailable, recent research has shown that both violent offenders and victims are much older in Russia than in the U.S. (Pridemore, 2003a). Based upon this research, we included a control for the proportion of the population male aged 25–44 (Goskomstat, 2001b). Finally, relative to the rest of the nation, crime rates have been shown to be lower in the Northern Caucasus and higher in the regions east of the Ural Mountains (Pridemore, 2002), so we included two regional dummy variables to control for these differences.

Missing data

Northern Osetia had missing data on foreign investment and the Chukot Okrug on foreign investment and education. To retain these cases for analysis, we replaced missing values by using the other regressors in the model as instrumental variables. We regressed the variable with the missing observation on all other independent variables that had complete data and used the predicted values to replace these three missing observations (Pindyck and Rubinfeld, 1998).

Model estimation

We first used exploratory data analysis to examine the distributions of the independent variables and the direction, strength, and linearity of any relationships between the independent and dependent variables. We found that several of the variables were positively skewed. Education, polity, development, inequality, and males 25–44 had skew statistics at least twice their standard errors and so we took their natural log to help normalize their distributions. We then used OLS regression to estimate the effects of socioeconomic change, institutional strength, and the interaction terms (i.e., negative socioeconomic change × family, education, and polity, respectively) on both sets of robbery rates.

Results

Table 1 shows that the mean regional armed robbery and robbery rates in 2000 were 26 and 90 per 100,000 residents, respectively. Unexpectedly, the correlation matrix in Table 2 reveals no correlation between negative socioeconomic change and armed robbery and robbery rates. This runs counter to Durkheimian anomie theory, related strain theories, and Kim's (2003) findings that showed a positive cross-sectional association between negative socioeconomic change and homicide rates in Russia. There is also no meaningful correlation between the measures of family and educational strength and either robbery rate. The small correlations that do exist are in fact positive. The one social institution negatively correlated with both crimes was polity (r=−.41 for armed robbery, r=−.45 for robbery).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix (n=78).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Armed | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. Robbery | .753 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. SE change | −.058 | −.123 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. Family | .104 | .135 | −.202 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. Log education | .058 | .091 | −.045 | .045 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. Log polity | −.406 | −.453 | .190 | −.193 | .039 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. Log inequality | .129 | .132 | −.045 | .036 | .386 | −.054 | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. Alcohol | .318 | .376 | .115 | −.030 | −.300 | −.256 | −.250 | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. Urban | .292 | .164 | −.033 | .189 | .652 | −.132 | .337 | −.131 | 1.00 | |||

| 10. Log males | .042 | .217 | −.137 | .047 | −.196 | −.338 | −.012 | .034 | −.019 | 1.00 | ||

| 11. Caucasus | −.085 | −.322 | −.152 | −.135 | .135 | .261 | .093 | −.413 | −.154 | −.371 | 1.00 | |

| 12. East | .143 | .348 | −.236 | −.096 | −.014 | −.384 | .069 | .058 | −.159 | .427 | −.212 | 1.00 |

Tables 3 (armed robbery) and 4 (robbery) show the results of model estimation. The four models in each table are the same, with the exception that Models 2–4 include the interaction terms one by one. The findings yield no support for the hypothesis that negative socioeconomic change is related to the cross-sectional variation of either robbery rate. The results provide partial support for the hypothesis that institutional strength has direct negative effects on crime rates. Single-parent households, which have been shown to be strongly associated with regional homicide rates in Russia (Pridemore, 2002), are unrelated to robbery rates. Educational strength does not appear to be associated with robbery rates, though the results for armed robbery are in the expected direction and p-values are less than .10 in two of the models. Partial support for the hypothesis comes from the significant and negative association between polity and both robbery rates, with βs ranging from −.20 to −.25. This finding for polity is consistent with that found for the direct effect of polity on regional homicide rates in Russia (Kim, 2003). Although the results from the bivariate correlations and the direct effects models now lead us to expect no significant conditioning effects of institutional strength on the relationship between negative socioeconomic change and crime rates, we nevertheless estimated the models to test the third hypothesis. Models 2–4 in each table show that the results for the interaction terms were all non-significant.

Table 3.

Results for armed robbery rates regressed on socioeconomic change, social institutions, and interaction terms (n=78).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value |

| Constant | 167.247 | .041 | 182.217 | .027 | 165.106 | .042 | 166.601 | .041 |

| SE change | 0.382 | .707 | 0.483 | .633 | 13.064 | .138 | 0.371 | .714 |

| Family | 23.045 | .661 | 23.931 | .646 | 23.931 | .646 | 21.012 | .688 |

| Log education | −4.600 | .158 | −5.637 | .090 | −5.637 | .090 | −4.752 | .144 |

| Log polity | −39.713 | .038 | −42.018 | .028 | −42.018 | .028 | −40.076 | .036 |

| Log inequality | 3.492 | .406 | 3.672 | .379 | 3.672 | .379 | 4.567 | .286 |

| Alcohol | 0.212 | .003 | 0.208 | .003 | 0.208 | .003 | 0.211 | .003 |

| Urban | 29.029 | .003 | 27.814 | .004 | 27.814 | .004 | 29.433 | .002 |

| Log males | −10.046 | .561 | −9.418 | .582 | −9.418 | .582 | −10.134 | .555 |

| Caucasus | 8.343 | .054 | 8.321 | .053 | 8.321 | .053 | 8.635 | .046 |

| East | 4.224 | .144 | 3.975 | .166 | 3.975 | .166 | 4.505 | .119 |

| SE change × Family | 81.566 | .147 | ||||||

| SE change × Education | −0.816 | .147 | ||||||

| SE change × Polity | −23.884 | .212 | ||||||

Further analysis and model sensitivity

Though the results are not presented here, the null findings outlined above led us to undertake further analyses to examine the effect of absolute deprivation (as well as the interaction of deprivation and institutional strength) on property crime rates for several reasons. First, previous research in Russia has shown a consistently strong and positive effect of poverty on the cross-sectional variation of violent crime (Pridemore, 2002). Second, we might expect property crime rates to be more sensitive to economic deprivation as opposed to general socioeconomic change. Finally, although we agree with Bernburg (2002) that Messner and Rosenfeld's theory is appropriate to test in the context of social change (i.e., we initially believed that strong institutions might moderate the effect of negative socioeconomic change on crime), previous tests of the theory have used measures of economic deprivation. When we replaced socioeconomic change with a measure of the proportion of the population living below the poverty line and reestimated the models, however, we received the same results. Absolute deprivation was not related to the cross-sectional variation of either robbery rate, nor were the interaction terms testing institutional anomie significant.2

In order to see if our construction of the negative socioeconomic change index might have affected its association with robbery and its interaction with measures of institutional strength, we created an alternative index that simply summed the z-scores of the variables' original values. The results for the new index were the same: no association with either set of robbery rates. Similarly, we decided to create an overall robbery rate by summing the two different rates used here. Again, the results showed null effects on this outcome variable for socioeconomic change, poverty, and their interaction terms with the institutional variables.

A final alternative specification deals with using a dynamic independent variable and a static dependent variable. That is, our index represents changes over time whereas the dependent variable in these models is for one year (i.e., robbery rates in 2000). It would be ideal to create a model where all independent variables represented change scores, but such data were unavailable. In order to partially account for this we included as a control the 1992 robbery rate. There were no meaningful changes from the results shown here when this control was included.3

Finally, we used several diagnostics to test the stability of the models. The diagnostics revealed no serious departures from the OLS assumptions. When estimating models with the interaction terms, however, there was a high degree of multicollinearity, so we mean-standardized those variables in each model that were employed to create the interaction terms, thereby purging them of any non-essential collinearity (Jaccard and Turrisi, 2003). When the models were reestimated with these values, the variance inflation factors were well below conservative thresholds (the highest in any model was 2.4). Finally, we also used several methods to search for outliers and undue influence on the regression line (Pindyck and Rubinfeld, 1998). These tests suggested that Moscow may be an outlier, but there were no meaningful differences in the inferences drawn when Moscow was excluded.

Discussion and conclusion

Negative socioeconomic change

Durkheimian anomie theory suggests that rapid social change has criminogenic effects on a population. Thus the first hypothesis we test is that Russian regions that have experienced the more negative effects of socioeconomic change will have higher robbery rates. Unexpectedly, we find non-significant associations across all models. Similar models that replaced the change index with absolute deprivation also resulted in null findings. The results are even more surprising given the consistently strong and positive association between negative socioeconomic change and homicide in Russia found by Kim (2003) and similar results for the effects of poverty on homicide rates found by Pridemore (2002).

One interpretation of this is that socioeconomic change has had more of an impact on violence than on property crime. Descriptive data lend some support to this idea, since crime data from the Russian Ministry of the Interior show that rates of property-related crime did not increase as much as homicide rates following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This interpretation also finds support in recent empirical findings showing that social capital is closely associated with violent but not property crimes (Wilkinson, Kawachi, and Bruce, 1998). These results may indicate that negative socioeconomic change and uncertainty may have more of an effect on frustration, anger, and self-destructive behavior (e.g., drinking) that result in more expressive violent crimes relative to instrumental acquisitive crimes

Social institutions

The second hypothesis relates to the direct effect of social institutions on property crime. Results show that the strength of social institutions has a limited effect on the regional variation of Russian property crime rates. Neither family nor educational strength is related to robbery rates. On the other hand, there is a negative association between polity and robbery. Russia shows considerable geographic variation in political behavior such as party preference and voter turnout (Clem and Craumer, 1997). Given the communal nature of political behavior (Huckfeldt, Beck, Dalton, and Levine, 1995; Mutz, 1998), regions with higher voter turnout may possess stronger solidarity and thus greater cohesion and control (Marwell, Oliver, and Prahl, 1988; McPherson, Popielarz, and Drobnic, 1992). Since it might also be argued in the context of transitional Russia that higher turnout actually means greater discontent, we note that this does not appear to be the case since there is a weak correlation (r=.11, not shown in the correlation matrix) between voter turnout and proportion of the vote going to the communist party candidate. Thus no matter for whom the electorate is voting, higher voter turnout is associated with lower rates of both armed robbery and robbery.

Overall, these results differ from studies testing institutional anomie theory with property crime in the United States. Chamlin and Cochran (1995) found that religion and family had direct effects on property crime but polity did not. Piquero and Piquero (1998) found that polity, education, and family all had direct effects on property crime. The differences might be understandable given the current conditions in Russia. Whereas the United States is a stable society, which better allows social institutions to fulfill their roles more effectively, the sweeping changes in Russia were rapid and severe, potentially making it difficult for social institutions to function efficiently in the face of paradigmatic change.

Institutional anomie

Following the suggestion of Bernburg (2002), we extended institutional anomie theory to include socioeconomic change, assessing it indirectly by testing the hypothesis that institutional strength conditions the effect of negative socioeconomic change on property crime. The results show that none of the interaction terms is significantly related to robbery. Hence, social institutions do not appear to condition the effects of socioeconomic change on property crime in transitional Russia. Our results differ from those of Chamlin and Cochran (1995), who showed that religion, family, and polity conditioned the effects of economic deprivation on property crime, and those of Piquero and Piquero (1998), who showed that education conditioned the effects of the economy on property crime. In our case, the non-significant results of the interaction terms turn out not to be a surprise, since our initial models show no direct effects of negative socioeconomic change (or of poverty) on robbery.

Limitations

There are a few possible limitations to consider when interpreting our results. The first is measurement, and most importantly measurement of the dependent variable. The data on regional robbery rates are provided by the Russian Ministry of the Interior. During the Soviet era, local officials had a history of falsifying crime data to please superiors (Shelley, 1980) and the Ministry itself either kept crime data secret or manipulated them for public consumption (Butler, 1992). Although the transparency of the Russian government is increasing with the transition to democracy and rule of law, and although general crime data are now publicly available, the validity of these data has yet to be closely scrutinized and there may still be irregularities. For example, decreased budgets and increased crime rates during the transition depleted human and technological resources, leaving police with the inability to properly investigate all crimes reported to them. This may result in under-reporting on the part of the public as they lose faith in the ability of the police to solve the crime and under-recording on the part of the police since they may lack the necessary resources to complete the investigation (Pridemore, 2003b). Less innocently, high crime rates and public concern about them provide motives for local officials to falsify crime data, especially since performance assessments often are based on clearance rates. While we report these concerns here and understand that the inferences drawn from our analyses must take this into account, we also recognize the merit of these newly available data for initial examination of crime in Russia, given the impossibility of such an undertaking until very recently. We also attempt to minimize these potential problems by not using lesser crimes such as theft.

Two further limitations common to any ecological analysis such as ours include aggregation bias and spatial autocorrelation. The former results from grouping by area (e.g., cities, states, countries) and the inability to control for individual effects (Blalock, 1979; Robinson, 1950), thus resulting in regression coefficients that may not represent purely structural effects. Spatial autocorrelation may occur when the observed cases are structured relative to one another. In this context, neighboring regions may have correlated residuals since they likely possess similar attributes and are influenced by similar conditions (Berry, 1993; Chatterjee, Hadi, and Price, 2000). This problem has long been recognized but has only recently begun to attract attention in the social structure and crime literature (Anselin, Cohen, Cook, Gorr, and Tita, 2000; Messner, Anselin, Baller, Hawkins, and Deane, 1999).

Finally, institutional anomie theory was not developed to explain the relationship between socioeconomic change and crime. Instead, it focuses on cultural pressures for monetary success, the dominance of the economy in the institutional balance of power, and the interaction of these cultural and institutional structures. Nevertheless, Bernburg (2002) argues that Messner and Rosenfeld's theory provides an important link between anomie, contemporary social change, and crime due to its consideration of an unchecked market economy, which we thought might be an important facet of the cultural change in Russia resulting from the sudden transition to a free market economy and Western ideals.

Future research

Our analyses lead to a few specific points about crime in Russia that demand further research scrutiny. First and foremost is the measurement issue. Pridemore (2003b) has examined measurement-related issues for homicide in Russia, but more careful study of the validity of other crime data is of major importance for those interested in examining the change in and high rates of crime in the country.

Second, alternative research designs and model specifications could provide different results. For example, while negative socioeconomic change does not appear to have a cross-sectional effect on property crime, time-series analysis should be undertaken to see if these changes and the sudden impoverishment of a large segment of the population were related to the increase in property crime rates in the early 1990s shown in Figure 1. Further, it may be the present model may require some structure to provide a more nuanced understanding of any relationships between these variables. It may be that negative socioeconomic change weakens social institutions, thereby reducing or negating their ability to protect against crime and thus mediating the impact of economic change. Similarly, many researchers (Gavrilova, Semyonova, Evdokushkina, and Gavrilov, 2000; Leon and Skolnikov, 1998) argue that social and political change, repeated economic crises, and continued uncertainty in Russia played a role in increased alcohol consumption during the 1990s, which in turn appears to be related to crime rates (based on its consistent association with robbery rates here and upon its strong association with regional homicide rates shown by Pridemore, 2002), thus suggesting an indirect effect of socioeconomic change and/or impoverishment on crime via alcohol consumption.

Finally, closer examination of our control variables and tests of other theoretical explanations present promising avenues for further research. Other theories at both the individual- and group-level may be appropriate to test under these conditions since Russia offers researchers an excellent laboratory for the study of the impact on individuals and society of political, economic, and social change. More generally, careful criminological research in Russia and other countries will yield important theoretical and empirical findings that extend beyond a single nation. This process provides more information about crime measurement in specific countries, thereby providing a stronger foundation upon which to undertake comparative work. It also allows us to test the generalizability of criminological theories developed to explain crimes in Western nations (usually the U.S.). We will thus be able to discover what conditions appear to operate similarly across nations to generate crime, as well as how differences in local context and varying cultures influence rates of crime and violence.

Table 4.

Results for robbery rates regressed on socioeconomic change, social institutions, and interaction terms (n=78).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value |

| Constant | 656.476 | .058 | 721.704 | .038 | 647.150 | .059 | 654.454 | .059 |

| SE change | −2.105 | .626 | −1.668 | .697 | 53.151 | .154 | −2.141 | .620 |

| Family | 174.116 | .435 | 177.976 | .421 | 177.976 | .421 | 167.752 | .453 |

| Log education | 12.539 | .362 | 8.021 | .565 | 8.021 | .565 | 12.063 | .382 |

| Log polity | −145.254 | .073 | −155.294 | .054 | −155.294 | .054 | −146.387 | .071 |

| Log inequality | 21.303 | .233 | 22.084 | .213 | 22.084 | .213 | 24.665 | .178 |

| Alcohol | 0.915 | .003 | 0.896 | .003 | 0.896 | .003 | 0.912 | .003 |

| Urban | 16.010 | .685 | 10.717 | .785 | 10.717 | .785 | 17.275 | .662 |

| Log males | 19.063 | .794 | 21.797 | .764 | 21.797 | .764 | 18.787 | .797 |

| Caucasus | −11.090 | .541 | −11.189 | .534 | −11.189 | .534 | −10.177 | .576 |

| East | 20.831 | .090 | 19.746 | .105 | 19.746 | .105 | 21.712 | .079 |

| SE change × Family | 355.397 | .136 | ||||||

| SE change × Education | −3.554 | .136 | ||||||

| SE change × Polity | −74.749 | .358 | ||||||

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grant #1 R21AA013958-01A1 awarded to the second author by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Points of view do not necessarily represent the official position of NIH/NIAAA. The authors thank Kelly Damphousse, Harold Grasmick, Wil Scott, and Brian Taylor for their helpful critiques of earlier drafts. The second author thanks the Davis Center at Harvard University, where he was a Research Fellow when this article was written.

A decreasing population was considered "negative" since it usually denotes a concentration of poverty as people with greater resources move out of undesirable places (Centerwall, 1992; Wilson, 1996) and leave behind a higher proportion of economically dependent residents. This has been shown to be the case for regional mobility in Russia (Andrienko and Guriev, 2004).

Yet another alternative explanation is that property crimes might actually be higher in more prosperous areas as a result of more targets/opportunities (Cohen and Felson, 1979). DiCristina (2004) points out that Durkheim made similar statements, suggesting that societal development might lead to more acquisitive crimes given increasing targets. Our coding of privatization and foreign investment would not allow us to determine if such an association exists. We therefore estimated a model without the index but with the original values of these two measures. That there was no positive relationship between robbery rates and any of the economic variables (i.e., poverty, privatization, or foreign investment) suggests this hypothesis does not hold in this context. On the other hand, the results in Table 3 show that armed robbery rates were significantly higher in regions with more urban residents. This is not the case for homicide in Russia, where rural homicide rates are as high or higher than in urban areas (Chervyakov et al., 2002). This might be interpreted as providing partial support for the idea that places with a greater number of and more accessible targets (i.e., dense urban areas) create better circumstances to commit instrumental crimes with monetary rewards (Felson, 1994). Taken together with the Chervyakov et al. findings, this coincides with Kposowa, Breault, and Harrison (1995), who found that urbanism is more strongly related to property crime than to homicide.

We also created a residual change score for robbery rates using the methods discussed above. The correlation between the change index and the change scores for robbery were very weak.

Contributor Information

Sang-Weon Kim, Dong-Eui University, Department of Police Science, 995 Eomgwangno, Busanjin-gu, Busan 614-774, Korea, sangkim@mail.deu.ac.kr.

William Alex Pridemore, Indiana University, Department of Criminal Justice, Sycamore Hall 302, Bloomington, IN 47405, wpridemo@indiana.edu.

References

- Andrienko Y. Understanding the crime growth in Russia during the transition period: A criminometric approach. Ekonomicheskiy Zhurnal Vyshey Shkoly Ekonomiki. 2001;5:194–220. [Google Scholar]

- Andrienko Y, Guriev S. Determinants of interregional mobility in Russia. The Economics of Transition. 2004;12:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin L, Cohen J, Cook D, Gorr W, Tita G. Criminal justice 2000, Vol. 4: Measurement and analysis of crime and justice. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice; 2000. Spatial analyses of crime. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan ST. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1997. Criminology: A sociological understanding. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah RN, Madsen R, Sullivan W, Swidler A, Tipton S. New York: Vintage Books; 1991. The good society. [Google Scholar]

- Bernburg JG. Anomie, social change, and crime: A theoretical examination of institutional-anomie theory. British Journal of Criminology. 2002;42:729–742. [Google Scholar]

- Berry WD. (Sage University Paper series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Science, series no. 07–092) Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. Understanding regression assumption. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock HM. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1979. Social statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, McKee M, Rose R, Marmot M. Alcohol consumption in a national sample of the Russian population. Addition. 1999;94:857–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohrnstedt GW. Observations on the measurement of change. Sociological Methodology. 1969;1:113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Butler WE. Crime in the Soviet Union: Early glimpses of the true story. British Journal of Criminology. 1992;32:144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Centerwall BS. Race, socioeconomic status, and domestic homicide. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;273:1755–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamlin MB, Cochran JK. Assessing Messner and Rosenfeld’s institutional anomie theory: A partial test. Criminology. 1995;33:411–429. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Hadi AS, Price B. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. Regression analysis by example. [Google Scholar]

- Chervyakov V, Shkolnikov V, Pridemore W, McKee M. The changing nature of murder in Russia. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1713–1724. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubais A, Vishnevskaya M. Main issues of privatization in Russia. In: Aslund A, Layard R, editors. Changing the economic system in Russia. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1993. pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Clem RS, Craumer PR. The regional dimension. In: Belin L, Orttung RW, editors. The Russian parliamentary elections of 1995: The battle for the Duma. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe; 1997. pp. 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, Felson M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:588–608. [Google Scholar]

- Currie E. Crime in the market society. Dissent (Spring) 1991:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- DiCristina B. Durkheim's theory of homicide and the confusion of the empirical literature. Theoretical Criminology. 2004;8:57–91. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. New York: Free Press; 18971979. Suicide: A study in sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Felson M. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 1994. Crime and everyday life: Insights and implications for society. [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh G, Beck F. Does economic growth benefit the masses: Growth, dependence, and welfare in the third world. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:631–654. [Google Scholar]

- Frey RS, Field C. The determinants of infant mortality in the less developed world: A cross-sectional test of five theories. Social Indicators Research. 2000;52:215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova NS, Semyonova V, Evdokushkina GN, Gavrilov LA. The response of violent mortality to economic crisis in Russia. Population Research and Policy Review. 2000;19:397–419. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhberg L, Kovaleva N, Mindeli L, Nekipelova E. Moscow: Center for Science Research and Statistics; 2000. Qualified manpower in Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MI. 2nd ed. New York: Norton; 1996. Lost opportunity: What has made economic reform in Russia so difficult. [Google Scholar]

- Goskomstat . Moscow: Author; 1998. Rossiiskoi statisticheskii ezhegodnik. [Russian statistical yearbook] [Google Scholar]

- Goskomstat Moscow: Author; 2001a. Rossiiskoi statisticheskii ezhegodnik. [Russian statistical yearbook] [Google Scholar]

- Goskomstat . Moscow: Author; 2001b. Chislennost' naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii: Po goradam, rabochim poselkam i raionam 1 Yanvarya 2000g. [The population of the Russian Federation: By city, workers' settlements, and regions on 1 January 12000. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SE. Analyzing post-communist economic change: A review essay. East European Politics and Societies. 1998;12:145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Heleniak T. Internal migration in Russia during the economic transition. Post-Soviet Geography. 1997;38:81–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heleniak T. Economic transition and demographic changes in Russia, 1989–1995. Post-Soviet Geography. 1995;36:446–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckfeldt R, Beck PA, Dalton RJ, Levine J. Political environments, cohesive social groups, and the communication of public opinion. American Journal of Political Science. 1995;39:1025–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Intriligator MD. Privatization in Russia has led to criminalization. The Australian Economic Review. 1994;106:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Turrisi R. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, series no. 07–072. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. Interaction effects in multiple regression. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW. Department of Sociology, University of Oklahoma; 2003. Anomie, institutions, and crime: The role of social institutions in the relationship between socioeconomic change and crime in Russia. Unpublished dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Kposowa AJ, Breault KD, Harrison BM. Reassessing the structural covariates of violent and property crimes in the USA: A county level analysis. The British Journal of Sociology. 1995;46:79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lafree G. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1998. Losing legitimacy: street crime and the decline of social institutions in America. [Google Scholar]

- Leon DA, Shkolnikov VM. Social stress and the Russian mortality crisis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:790–791. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwell G, Oliver PE, Prahl R. Social networks and collective action: A theory of the critical mass. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:502–534. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson JM, Popielarz PA, Drobnic S. Social networks and organizational dynamics. American Sociological Review. 1992;57:153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review. 1938;3:672–682. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. New York: Free Press; 1968. Social theory and social structure. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Anselin L, Baller R, Hawkins D, Deane G, Tolnay S. The spatial patterning of county homicide rates: An application of exploratory spatial data analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1999;15:423–450. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. 2nd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1997a. Crime and the American dream. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. Political restraint of the market and levels of criminal homicide: A cross-national application of Institutional-Anomie theory. Social Forces. 1997b;75:1393–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ. Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Social Forces. 1997;76:31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz DC. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Impersonal influence: How perceptions of mass collectives affects political attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- Orttung RW, editor. New York: EastWest Institute; 2000. The republics and regions of the Russian federation: A guide to politics, policies, and leaders. [Google Scholar]

- Pindyck R, Rubinfield D. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill; 1998. Econometric models and economic forecasts. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A, Piquero NL. On testing institutional anomie theory with varying specifications. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention. 1998;7:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi K. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2001. The great transformation: The political and economic origins of our times. [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore WA. Vodka and violence: Alcohol consumption and homicide rates in Russia. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1921–1930. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore WA. Demographic, temporal, and spatial patterns of homicide rates in Russia. European Sociological Review. 2003a;19:41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore WA. Measuring homicide in Russia: A comparison of estimates from the crime and vital statistics reporting system. Social Science & Medicine. 2003b;57:1343–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore WA, Spivak AL. Patterns of suicide mortality in Russia. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:132–150. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.2.132.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WS. Ecological correlation and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review. 1950;15:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Russian Ministry of Health. Moscow: Author; 2001. Smertnost’ naseleniia Rossiiskoi Federatsii, 2000 god. [Population mortality of the Russian Federation, 2000] [Google Scholar]

- Russian Ministry of the Interior. Moscow: Author; 2001. Prestupnost' i pravonarusheniya 2000: Statisticheskii sbornik. [Crimes and offenses 2000: Statistical collection] [Google Scholar]

- Sagers MJ. Regional industrial structures and economic prospects in the former USSR. Post-Soviet Geography. 1992;33:487–515. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen J. Inequality, welfare state, and homicide: Further support for the institutional anomie theory. Criminology. 2000;38:1021–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley L. The geography of Soviet criminality. American Sociological Review. 1980;45:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnikov VM. Geograficheskie faktori prodolzhitelnosti (Geographical factors of length of life) Izvestiya AN SSR, Geographical Series. 1987;3:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnikov VM, McKee M, Leon DA. Changes in life expectancy in Russia in the mid-1990s. Lancet. 2001;357:917–921. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnikov VM, Meslé F. The Russian epidemiological crisis as mirrored by mortality trends. In: DaVanzo J, editor. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 1996. pp. 113–162. Russia’s demographic “crisis”. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S, Bankowski E. Divorce and drinking: An analysis of Russian data. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:805–812. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal A. Political competition and violence in Mexico: Hierarchical social control in local patronage structure. American Sociological Review. 2002;67:447–498. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Kawachi I, Bruce PK. Mortality, the social environment, crime and violence. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1998;20:578–597. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. New York: Knopf; 1996. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. [Google Scholar]