Abstract

Activation of phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) in endothelial cells in part is responsible for angiogenesis in vivo. The cellular mechanisms exerting negative control over PLCγ1 activation, however, remain unaddressed. Here by using in vitro and in vivo binding assays, we show that the Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (c-Cbl) E3 ubiquitin ligase constitutively associates with PLCγ1 via its C-terminal domain and conditionally interacts with VEGFR-2 via the N-terminal/TKB domain. Site-directed mutagenesis of VEGFR-2 showed that full activation of c-Cbl requires its direct association with phospho-tyrosines 1052 and 1057 of VEGFR-2 via its TKB domain and indirect association with phospho-tyrosine 1173 of VEGFR-2 via PLCγ1. The tertiary complex formation between VEGFR-2, PLCγ1 and c-Cbl selectively promotes ubiquitylation and suppression of tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 by a proteolysis-independent mechanism. Further analysis showed that association of c-Cbl with VEGFR-2 does not impact ubiquitylation, down-regulation, or tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR-2. Silencing of c-Cbl by siRNA revealed that endogenous c-Cbl plays an inhibitory role in angiogenesis. Our data demonstrate that corecruitment of c-Cbl and PLCγ1 to VEGFR-2 serves as a mechanism to fine-tune the angiogenic signal relay of VEGFR-2.

Keywords: ubiquitination

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, is of great importance in normal physiological processes and pathological conditions including tumor growth, rheumatoid arthritis and degenerative eye disorders (1). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in conjunction with its transmembrane receptors, plays a crucial role in regulation of these cellular events (1, 2). Activation of VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR-2/Flk-1/KDR) in endothelial cells orchestrates a wide variety of biological responses that emanate from several key autophosphorylation sites within the cytoplasmic domain of VEGFR-2. Recruitment, tyrosine phosphorylation, and subsequent activation of phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) by VEGFR-2 are essential for VEGFR-2-induced angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro (3–5). Indeed, a recent gene-targeting study using a knock-in strategy to replace the wild-type Flk-1 allele with a mutant Flk-1 allele harboring a point mutation in PLCγ1 binding site has demonstrated the physiological significance and essential role for PLCγ1 in angiogenesis (5). In earlier studies, mice nullizygous for Plcγ1 were subject to embryonic lethality due to significantly impaired vasculogenesis and erythrogenesis (6, 7). Finally, a study on zebrafish demonstrated that PLCγ1 is critically required for the function of VEGF and arterial development (8). However, it remains unknown how PLCγ1 activation is negatively regulated in endothelium. A major unresolved issue relates to negative regulation of PLCγ1 activation and to what extent VEGFR-2 simultaneously controls activation and inactivation of PLCγ1. Understanding how this molecular switch achieved is crucial for better understanding of the molecular basis of angiogenesis.

In this study, we have established that c-Cbl (Casitas B-lineage lymphoma) is distinctly involved in the modulation of VEGFR-2-driven angiogenesis. Our findings point toward a unique mechanism in which c-Cbl recruitment to VEGFR-2 inhibits PLCγ1 activation in an ubiquitylation-dependent, but in a proteolysis-independent mechanism leading to inhibition of angiogenesis.

Results

Activation of Ubiquitin E3 Ligase c-Cbl Inhibits PLCγ1 Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Promotes its Ubiquitylation.

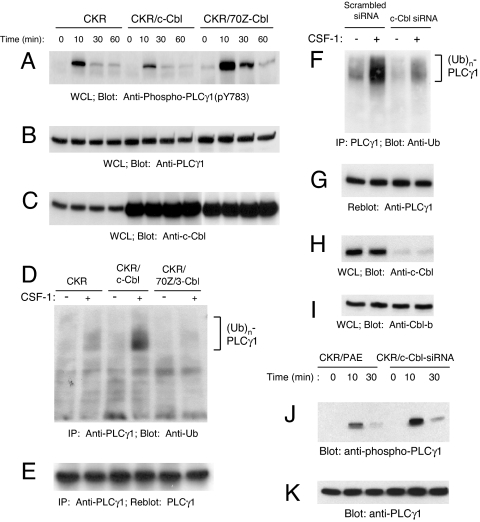

Tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 particularly at Y783 is an event critical for the up-regulation of PLCγ1 enzymatic activity (9) and correlates with VEGFR-2-induced angiogenesis (3–5). To investigate whether c-Cbl could modulate VEGFR-2-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1, we coexpressed either wild-type c-Cbl or an E3 ligase-deficient Cbl mutant, 70Z/3-Cbl, with the previously established VEGFR-2 chimera called CKR. The VEGFR-2 chimera was created by replacing the extracellular domain of VEGFR-2 with that of human CSF-1R and expressed in porcine aortic endothelial (PAE) cells as an experimental system (10). We used this strategy to avoid cross-talk between VEGFR-2 and other VEGF receptors including VEGFR-1, VEGFR-3, and neuropilins. This unique strategy allowed us to elucidate the selective signal transduction relay of VEGFR-2 in endothelial cells. Overexpression of c-Cbl reduces the CKR-dependent PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation at Y783 (Fig. 1A). In sharp contrast, overexpression of 70Z/3-Cbl (an E3 ligase deficient c-Cbl, acting as a dominant negative) promotes an up-regulation in CKR-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 at Y783, particularly after 10-min stimulation with CSF-1 (Fig. 1A). Overexpression of another E3 ligase-deficient c-Cbl mutant (C3HC4C5-Cbl), harboring multiple cysteine–alanine point mutations within the RING domain (11) also yielded results similar to those observed with 70Z/3-Cbl (data not shown). These data indicate that c-Cbl negatively regulates VEGFR-2-dependent phosphorylation of PLCγ1 and imply that E3 ligase activity of c-Cbl is necessary for its negative regulatory effect. Next, we investigated the potential role of c-Cbl in ubiquitylation of PLCγ1. Fig. 1D shows that PLCγ1 undergoes ubiquitylation upon VEGFR-2 activation with ligand and overexpression of wild-type c-Cbl enhances the incorporation of ubiquitin by PLCγ1. In contrast, overexpression of 70Z/3-Cbl abolishes ligand-dependent incorporation of ubiquitin by PLCγ1 (Fig. 1D). To corroborate these findings, we attempted to knockdown c-Cbl expression in PAE cells by siRNA strategy. c-Cbl siRNA specifically knockdowns expression of c-Cbl (Fig. 1H) without affecting expression of highly related protein, Cbl-b (Fig. 1I). Silencing the expression of c-Cbl by siRNA significantly reduces PLCγ1 ubiquitination (Fig. 1F) and enhances its VEGFR-2-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1J). The data demonstrate that c-Cbl E3-ligase activation inhibits VEGFR-2-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1.

Fig. 1.

c-Cbl inhibits PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation and promotes its ubiquitylation in endothelial cells. (A) PAE cells expressing either CKR (chimeric VEGFR-2) alone, coexpressing the wild-type Cbl or 70Z/3-Cbl were either unstimulated or stimulated with CSF-1 for various times as indicated. PLCγ1 activation in normalized whole cell lysates (WCL) was analyzed by immunoblotting with a phospho-specific (pY783) PLCγ1 antibody. (B) PLCγ1 expression in whole cell lysates was determined in a parallel immunoblot using an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. (C) overexpression of c-Cbl and 70Z/3-Cbl proteins was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-c-Cbl antibody. (D) PLCγ1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from RIPA whole cell lysates and was assessed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody. (E) The blot shown in D was stripped and reprobed with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody to demonstrate equal amounts of immunoprecipitated PLCγ1. (F) CKR/PAE cells were retrovirally transduced with either constructs expressing a control siRNA (Scrambled siRNA) or a siRNA targeting c-Cbl (c-Cbl siRNA). The aforementioned cell lines were left either unstimulated or stimulated for 10 min, immunoprecipitated with anti-PLCγ1 antibody, and immunoblotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody. (G) The same membrane was immunoblotted with anti-PLCγ1 antibody. (H and I) Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-c-Cbl (H) or anti-Cbl-b (I) antibodies. (J and K) CKR/PAE cells and CKR/PAE cells expressing c-Cbl-siRNA were stimulated with CSF-1 for various times as indicated, and whole cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting with a phospho-specific (pY783) PLCγ1 antibody (J) or with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody (K).

Activation of Ubiquitin E3 Ligase c-Cbl Is Not Associated with Proteolysis of PLCγ1.

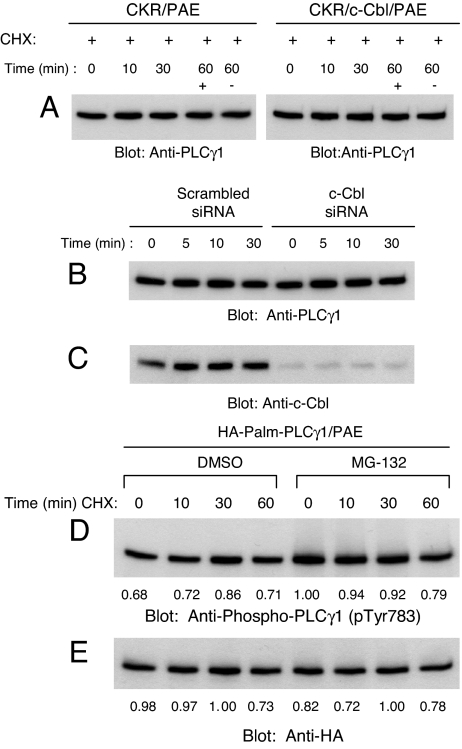

To analyze whether c-Cbl-dependent ubiquitination of PLCγ1 serves as a mechanism to regulate its degradation, we evaluated proteolysis of PLCγ1. Using PAE cells overexpressing c-Cbl or c-Cbl-specific siRNA, we show that c-Cbl-dependent ubiquitination of PLCγ1 does not translate into an apparent decrease in total PLCγ1 protein levels (Fig. 2 A and B). The data suggest that either PLCγ undergoes c-Cbl-dependent ubiquitination without degradation, or only a small percentage of c-Cbl-associated PLCγ1 undergoes for degradation. To test for the later possibility, we incubated PAE cells expressing a constitutively active HA-tagged PLCγ1 (palmitoylated and myristoylated PLCγ1) with MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, and analyzed its tyrosine phosphorylation. MG-132 treatment enhanced PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation to some extent without an apparent effect on the PLCγ1 protein levels as demonstrated by anti-HA immunoblotting (Fig. 2 D and E, respectively). We took this approach because treatment of PAE cells expressing CKR with MG-132 enhances CKR protein stability and its tyrosine phosphorylation (12), making it difficult to assess direct effect of MG-132 in PLCγ1 degradation and tyrosine phosphorylation. Altogether, these data establish that c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitylation of PLCγ1 provides a mechanism to regulate VEGFR-2-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 in endothelial cells in a proteolysis independent mechanism.

Fig. 2.

c-Cbl E3 ligase activity is not associated with proteolysis of PLCγ1. (A) PAE cells either expressing wild-type CKR alone or coexpressing c-Cbl were treated with CHX (20 μg/ml) and CSF-1 for indicated times and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. (B) PAE and CKR/PAE cells expressing either a control siRNA (CKR/Scrambled siRNA) or a siRNA targeting c-Cbl (CKR/c-Cbl siRNA) were unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) with CSF-1 for indicated periods of time, and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. (C) A parallel immunoblot of whole cell lysate aliquots was probed with an anti-c-Cbl antibody. (D) PAE cells expressing constitutively active PLCγ1 (HA-Palm-PLCγ1) were preincubated for 2 h with either DMSO or MG-132 (50 μM) followed by a 30-min preincubation with CHX (20 μg/ml). Cells were then either lysed (0 min) or incubated in the continued presence of CHX for the indicated periods with or without MG-132. At each time point, whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-PLCγ1 antibody (pTyr783). (E) A parallel immunoblot of whole cell lysates was probed with an anti-HA antibody.

c-Cbl Constitutively Associates with PLCγ1, but its Association with VEGFR-2 Is Required for Inhibition of PLCγ1 Tyrosine Phosphorylation.

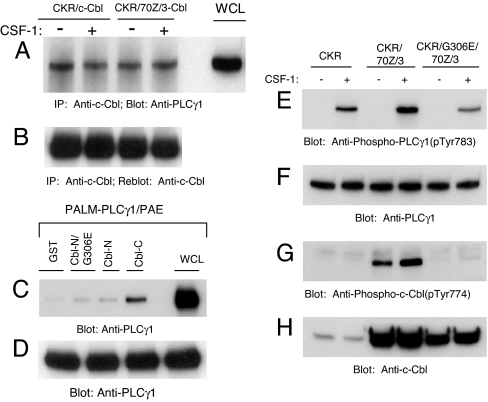

Because c-Cbl modulates the ubiquitylation and tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1, we wished to investigate their mechanism of interaction in endothelial cells. Fig. 3A shows that PLCγ1 coprecipitates with both the wild-type c-Cbl and 70Z/3-Cbl and its association with c-Cbl is independent of VEGFR-2 activation. Substrates of c-Cbl to be targeted for ubiquitylation interact with either its N-terminal TKB domain or the C-terminal proline-rich region (13). To address the relative contribution of these c-Cbl domains to associate with PLCγ1, we performed in vitro GST pull-down assays using GST alone (GST), GST fused to the Cbl N-terminal TKB domain (GST-Cbl-N) and its TKB-inactivated mutant (GST-Cbl-N/G306E), corresponding to a loss-of-function mutation (14), and GST fused to the c-Cbl C-terminal domain (GST-Cbl-C).

Fig. 3.

c-Cbl constitutively associates with PLCγ1 via its carboxyl domain. (A) CKR/c-Cbl/PAE and CKR/70Z/3-Cbl/PAE cells were either unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) for 10 min with CSF-1. Normalized whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-c-Cbl antibody and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. Positive controls consist of whole cell lysate (WCL) aliquots and are indicated as such. (B) The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-c-Cbl antibody. (C) PAE cells ectopically expressing constitutively active PLCγ1 (Palm-PLCγ1) were serum-starved overnight. Normalized whole cell lysates from each of the four dishes were incubated separately with equal amounts of GST, GST-Cbl-N/G306E, GST-Cbl-N, and GST-Cbl-C fusion proteins as indicated in an in vitro GST pull-down assay. Precipitated PLCγ1 was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. Positive controls consist of whole cell lysate aliquots and are indicated as such. (D) A parallel blot of whole cell lysates was probed with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody as a loading control. (E) PAE cells either expressing wild-type CKR alone or with the indicated Cbl constructs were either unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) for 10 min with CSF-1 and normalized whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-PLCγ1 antibody (pTyr783). (F) Parallel blot of whole cell lysates were probed with an anti-PLCγ1 antibody. (G and H) Phosphorylation of 70Z/3-Cbl and G306E-70Z/3-Cbl and their expression.

Because tyrosine phosphorylated PLCγ1 may coprecipitate with the isolated Cbl TKB and C-terminal domains through mutually exclusive interactions of the two proteins with activated VEGFR-2, determining the relative contribution of Cbl-TKB and Cbl-C binding to PLCγ1 in the context of VEGFR-2 is difficult. Therefore, we used a constitutively active (palmitoylated and myristoylated) PLCγ1 (15). Overexpression of constitutively active PLCγ1 (Palm-PLCγ1) in VEGFR-2-null PAE cells leads to its constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2D). In Fig. 3C, using lysates derived from Palm-PLCγ1/PAE cells, we demonstrate that GST-Cbl-C but not GST-Cbl-N is able to interact efficiently with PLCγ1. Additional in vitro GST pull-down assays showed that the GST-Cbl-C fusion protein was also able to interact with endogenous PLCγ1 derived from either unstimulated or stimulated CKR/PAE lysates, suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 is not required for it to interact with Cbl-C (data not shown). These data demonstrate that c-Cbl and PLCγ1 exist as a preformed complex in endothelial cells and imply that the SH3 domain of PLCγ1 and C-terminal proline-rich region of Cbl mediate the constitutive nature of this complex.

Because we found that c-Cbl and PLCγ1 interaction is constitutive in endothelial cells, we next wanted to address what domains of c-Cbl participate in the regulation of VEGFR-2-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1. Overexpression of Cbl-N encompassing the unique TKB domain of c-Cbl, was not sufficient to modulate the level of tyrosine phosphorylated PLCγ1 relative to that observed in the presence of endogenous c-Cbl [supporting information (SI) Fig. 7A], suggesting that the TKB domain of c-Cbl is required for its ability to modulate tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1. Upon further analysis, we found that not only did inactivation of the 70Z/3-Cbl TKB domain (G306E/70Z/3-Cbl) totally abolish the basal and VEGFR-2-dependent hyperphosphorylation observed with 70Z/3-Cbl (Fig. 3G) but it also compromised the ability of 70Z/3-Cbl to up-regulate VEGFR-2-dependent PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 3E).

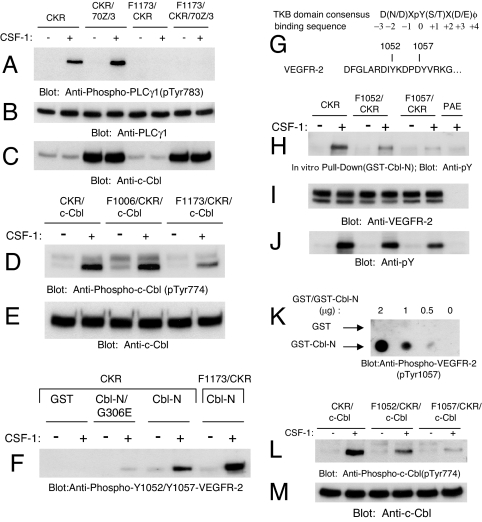

Because 70Z/3-Cbl up-regulates tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 and uncoupling its binding with VEGFR-2 (G306E/70Z/3-Cbl) abrogates its effect, we tested whether binding of PLCγ1 to VEGFR-2 is required for 70Z/3-Cbl to up-regulate its tyrosine phosphorylation. As shown (Fig. 4A), preventing the binding of PLCγ1 to VEGFR-2 (F1173/CKR) totally abolishes the ability of 70Z/3-Cbl to up-regulate VEGFR-2-dependent PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation. The data demonstrate that association of PLCγ1 with VEGFR-2 is required for 70Z/3-Cbl to enhance tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1. To test whether PLCγ1 association with VEGFR-2, in particular via phospho-tyrosine 1173, is required for tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl by VEGFR-2, we analyzed the ability of F1173/CKR to tyrosine phosphorylate c-Cbl. Fig. 4D shows that the presence phospho-tyrosine 1173 on VEGFR-2 is needed for maximal tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl. The data suggest that c-Cbl either directly binds to VEGFR-2 via phospho-tyrosine 1173 or indirectly associates with VEGFR-2 through PLCγ1. To test the later possibility, we analyzed binding of c-Cbl with VEGFR-2 in the context of F1173/CKR. The data show that tyrosine 1173 is not required for VEGFR-2 to interact with the TKB domain of c-Cbl (Fig. 4F). This finding strongly suggests that c-Cbl directly interacts with ligand-activated VEGFR-2 at an autophosphorylation site(s) other than Y1173 and that the ability of c-Cbl to down-regulate PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation does not occur through competition for phosphorylated tyrosine 1173. Finally, we tested whether c-Cbl and 70Z/3-Cbl differentially regulate VEGFR-2-dependent PLCγ1 tyrosine phosphorylation by modulating the tyrosine autophosphorylation sites on VEGFR-2. Our analysis revealed that the tyrosine phosphorylation including the key autophosphorylation sites on VEGFR-2 are not differentially phosphorylated in the context of overexpression of c-Cbl and 70z/3-Cbl with CKR (SI Fig. 8). These data indicate that neither c-Cbl nor 70Z/3-Cbl differentially regulate tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 by regulating the autophosphorylation status of key tyrosine residues on VEGFR-2, particularly the PLCγ1 SH2 domain-binding site at Y1173.

Fig. 4.

Role of tyrosines 1173, 1052, and 1057 of VEGFR-2 in the recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl. (A) PAE cells expressing CKR, F1173/CKR alone or coexpressing F1173/CKR with 70Z/3-Cbl were either unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) for 10 min with CSF-1, and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-PLCγ1 antibody (pTyr783). (B and C) Parallel blots of whole cell lysates were probed with an anti-PLCγ1 (B) and an anti-c-Cbl (C) antibodies to show their expression. (D) PAE cells coexpressing CKR with c-Cbl, F1006/CKR with c-Cbl, and F1173/CKR with c-Cbl were either unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) for 10 min with CSF-1, and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-c-Cbl antibody (pTyr774). (E) Parallel blot of whole cell lysates was probed with an anti-c-Cbl antibody. (F) CKR/PAE and F1173/CKR/PAE cells were treated as in A. Whole cell lysates were incubated with equal amounts of GST, GST-Cbl-N/G306E, and GST-Cbl-N fusion proteins as indicated in an in vitro GST pull-down assay. Precipitated CKR was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 antibody that detects VEGFR-2 autophosphorylated at Y1052 and Y1057 (pTyr1052/pTyr1057). (G) The c-Cbl TKB domain consensus binding sequence and a partial alignment of the activation loop primary amino acid sequence of VEGFR-2. (H) PAE cells expressing either wild-type CKR or the indicated activation loop mutants were unstimulated (−) or stimulated (+) for 10 min with CSF-1. Whole cell lysates were incubated with equal amounts of a GST-Cbl-N fusion protein in an in vitro GST pull-down assay. Cell lysates from CSF-1-stimulated PAE cells were used as a negative control. CKR·GST-Cbl-N complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (pY). (I) A parallel blot of whole cell lysates was probed with an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody (1412) as a control for receptor levels. (J) A parallel blot of whole cell lysates was probed with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (pY). (K) To detect a direct interaction between the Cbl TKB domain and VEGFR-2 activation loop tyrosines, the indicated quantities of purified recombinant GST control (Upper) and GST-Cbl-N fusion proteins (Lower) were dot blotted as described in Materials and Methods. (L and M) PAE cells coexpressing wild-type c-Cbl and either wild-type CKR or the indicated mutant receptors were treated as described in H. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted in parallel with anti-phospho-c-Cbl and anti-c-Cbl antibodies.

c-Cbl E3 Ligase Activity Is Not Involved in the Down-Regulation, Ubiquitylation, and Tyrosine Phosphorylation of VEGFR-2.

A recent study has demonstrated that VEGFR-2 undergoes c-Cbl independent down-regulation (12). In agreement with this study, we show that c-Cbl E3 ligase activity does not influence ligand-dependent down-regulation, tyrosine phosphorylation, or ubiquitylation of VEGFR-2 in the context of overexpression of c-Cbl and 70z/3-Cbl with CKR (SI Fig. 8 A–C). Consistent with these findings, silencing the endogenous c-Cbl expression in CKR/PAE cells using a siRNA-based approach showed that c-Cbl neither prevented nor delayed CSF-1-dependent degradation of CKR or its ubiquitylation (SI Fig. 8 E and G). Collectively, the data show that c-Cbl is not involved in ubiquitylation and down-regulation of VEGFR-2. Furthermore, the data demonstrate that c-Cbl-dependent inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 is not at the level of VEGFR-2.

Autophosphorylation of Tyrosines 1052 and 1057 Are Required for Recruitment and Tyrosine Phosphorylation of c-Cbl to VEGFR-2.

To identify the tyrosine autophosphorylation site(s) on VEGFR-2 involved in the recruitment of c-Cbl, we engineered a panel of VEGFR-2 in the background of chimeric VEGFR-2 (CKR) with single tyrosine to phenylalanine point mutations at either known or putative autophosphorylation sites. These mutant receptor constructs were tested for their ability to promote tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl. Initial study indicated that mutation of Y936, Y949, and Y994 to phenylalanine within the kinase-insert domain of VEGFR-2 did not affect the ability of the respective mutant receptors to phosphorylate overexpressed c-Cbl compared with wild-type CKR (SI Fig. 10B). Similarly, simultaneous elimination of Y1212, Y1221, Y1303, Y1307, and Y1317 in the context of the ΔCKR/147 and ΔCKR/147/F1212 constructs also did not significantly affect the ability of the respective mutant receptors to phosphorylate overexpressed c-Cbl compared with wild-type CKR (SI Fig. 10D).

The TKB domain of c-Cbl directly recognizes phosphotyrosine residues in the context of a D(N/D)XpY(S/T)X(E/D)φ consensus sequence, with D at −3 and N at −2 relative to the phosphotyrosine residue being the most important determinants of specificity (16). As shown in Fig. 4G, the primary amino acid sequence N-terminal to each of tyrosines 1052 and 1057 indicates that they may lie within a putative TKB domain binding site consensus sequence. To this end, we created single tyrosine to phenylalanine mutations in CKR at these sites to test the contribution of each of these tyrosine residues to TKB recruitment and c-Cbl phosphorylation. In vitro GST pull-down assays using a GST-Cbl-N fusion protein showed that the ability of the Cbl TKB domain to interact with activated F1052/CKR was significantly impaired as shown by the reduced signal following anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting (Fig. 4H). Similarly, the phosphotyrosine levels observed in F1057/CKR precipitates obtained after interaction with GST-Cbl-N were almost nonexistent as demonstrated by anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting (Fig. 4H). To further test whether tyrosines 1052 and 1057 participate in the direct recruitment of the c-Cbl TKB domain with VEGFR-2, we performed a dot blot assay in which PVDF-immobilized GST or GST-Cbl-N were overlaid with a pY1052/pY1057-VEGFR-2-derived peptide and then immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 antibody (pY1052) to detect the bound phospho-peptide. In Fig. 4K, although there was no detectable interaction between the phospho-VEGFR-2 peptide and the GST control, the immobilized GST-Cbl-N/TKB fusion protein was able to associate with the phospho-VEGFR-2 peptide. These data demonstrate that the c-Cbl TKB domain is capable of directly interacting with phosphorylated tyrosines 1052 and 1057 of VEGFR-2.

Because phosphorylation of tyrosines 1052 and 1057 appears to play a major role in the recruitment of the c-Cbl TKB domain in vitro, we wished to address the contribution of these sites to VEGFR-2-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl. As shown by anti-phospho-c-Cbl immunoblotting, the ability of activated F1052/CKR and F1057/CKR to promote tyrosine phosphorylation of overexpressed c-Cbl was compromised compared with wild-type CKR and correlated with the reduced capacity of these mutant receptors to bind the Cbl TKB domain. Tyrosine phosphorylation of overexpressed c-Cbl in the context of activated F1057/CKR was nearly eliminated (Fig. 4L). Collectively, these data make evident that pY1052 and pY1057 play a major role in regulating the tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl and recruitment of c-Cbl to VEGFR-2 via its TKB domain.

c-Cbl Inhibits Angiogenesis in Cell Culture System.

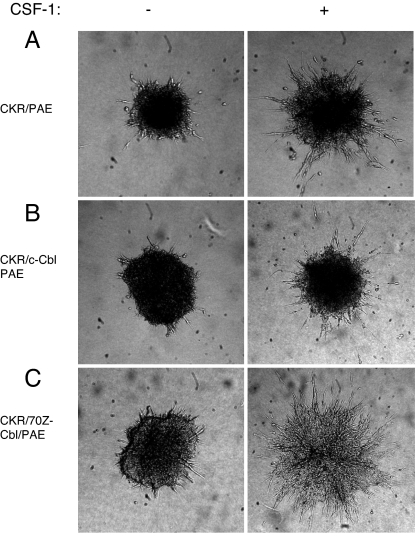

Activation of PLCγ1 is required for VEGFR-2-induced angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (3–5). To address the biological importance of modulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 by c-Cbl, we tested for its ability to inhibit VEGFR-2-induced angiogenesis. Using an in vitro angiogenesis assay, we demonstrate that overexpression of wild-type c-Cbl moderately inhibited the extent of endothelial cell sprouting and tubulogenesis (Fig. 5B) relative to what is observed in CKR/PAE cells (Fig. 5A). In startling contrast, overexpression of 70Z/3-Cbl dramatically enhanced endothelial cell sprouting and tube formation in response to CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. 5C). Overexpression of the N-terminal transforming region of c-Cbl (Cbl-N) did not modulate endothelial cell sprouting in response to CSF-1 (data not shown). Once again, even though Cbl-N and 70Z/3-Cbl are oncogenic E3 ligase-deficient c-Cbl variants, their ability to regulate CKR-dependent endothelial cell sprouting does not directly correlate with their transforming ability. To further link role of endogenous c-Cbl to angiogenesis, we analyzed the ability of CKR to induce angiogenesis in vitro where the expression of c-Cbl is silenced by siRNA strategy. Silencing the expression of c-Cbl in PAE cells resulted in significant cell sprouting and tubulogenesis, and that robust cell sprouting persisted for longer periods of time (60 h) in response to VEGFR-2 activation (compare Fig. 6B with D). Silencing the expression of c-Cbl in PAE cells also enhanced the basal cell sprouting and tubulogenesis (compare Fig. 6 A with C). The results indicate that endogenous c-Cbl in endothelial cells plays a negative role in VEGFR-2-mediated angiogenesis.

Fig. 5.

c-Cbl regulates VEGFR-2-driven angiogenesis in cell culture system. (A–C) PAE cells expressing either CKR alone, coexpressing wild-type c-Cbl, or coexpressing 70Z/3-Cbl were prepared as spheroids and subjected to an in vitro angiogenesis/tubulogenesis assay as described in Materials and Methods.

Fig. 6.

Silencing the expression of c-Cbl in endothelial cells enhances VEGFR-2-driven angiogenesis. PAE cells expressing either CKR alone or coexpressing c-Cbl-siRNA were prepared as spheroids and subjected to an in vitro angiogenesis/tubulogenesis as described in Fig. 5. Cells were either unstimulated, or stimulated with 40 ηg/ml CSF-1 (+CSF-1).

Discussion

Here, we show that c-Cbl is a binding partner and prominent substrate for activated VEGFR-2. Recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl by VEGFR-2, however, does not regulate ubiquitylation, degradation, or tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR-2. The study demonstrates that tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl by VEGFR-2 selectively promotes ubiquitylation of PLCγ1 and suppresses its tyrosine phosphorylation without an apparent effect on its protein stability and degradation. Ubiquitylation of PLCγ1 serves as a mechanism to inhibit its activity, which in turn antagonizes VEGFR-2-mediated angiogenesis. Although c-Cbl constitutively associates with PLCγ1, its ability to have an effect on PLCγ1 requires its association with VEGFR-2 via TKB domain. c-Cbl associates with VEGFR-2 by two distinctive manners; First, it directly associates with phosphorylated tyrosines 1052 and 1057 of VEGFR-2 via its TKB domain. Second, it interacts with VEGFR-2 via association with PLCγ1 involving tyrosine 1173 of VEGFR-2. In this regard, PLCγ1 serves as a bridge by acting as an “adaptor,” which in turn is essential for stable association of c-Cbl with VEGFR-2 and its full activation. Indirect association of c-Cbl with VEGFR-2 via PLCγ1 may account for the reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Cbl in the context of F1173/CKR.

The mechanism by which c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitylation of PLCγ1 suppresses its tyrosine phosphorylation and function is not clear, particularly because we did not observe a decline in total PLCγ1 protein levels. One possible explanation is that only a small percentage of the total cellular pool of c-Cbl-associated PLCγ1 is recruited to VEGFR-2 for activation and c-Cbl promotes ubiquitylation of this small, activated pool thus making it difficult to determine its stability. Alternatively, the ubiquitylation of PLCγ1 serves as signal for its rapid yet reversible inactivation through a proteolysis-independent mechanism. Incorporation of ubiquitin by PLCγ1 might hinder its tyrosine phosphorylation by making it less efficient substrate for VEGFR-2. c-Cbl can also negatively regulate the tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent activation of PLCγ by interfering competitively with the recruitment of its SH2 domains to phosphotyrosine binding sites on activated signaling complexes in a TKB domain-dependent manner (17). Our findings do not favor a competitive mechanism. An intact Cbl TKB domain directly associates with autophosphorylated VEGFR-2 predominantly at activation loop tyrosines Y1052/Y1057 rather than PLCγ1 binding sites at Y1006 and Y1173. Our findings also imply that, in addition to its E3 ligase activity, the C-terminal domain of c-Cbl encompassing amino acids 358–906 is critical for regulation of PLCγ1 activity. Recent work has indicated that p85/PI3K (18), PLCγ1 (3, 4), Shb (19), and Sck (20, 21) are directly recruited to this site. Ultimately, c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitylation and down-regulation of PLCγ1 could enhance the direct recruitment of other binding partners to this site and skew the balance among other biological signals transmitted by VEGFR-2 via pY1173.

VEGFR-2 activation in endothelial cells plays a central role in normal development and pathological angiogenesis (1, 2, 22). Our findings show that c-Cbl interacts with VEGFR-2 in an elaborate manner and has a conserved function in endothelial cells. Overexpression and knockdown of c-Cbl in endothelial cells revealed that c-Cbl is an integral part of VEGFR-2 angiogenic signaling system and its activation by VEGFR-2 is essential for tightly controlled angiogenic processes in endothelial cells. Our findings have opened possibilities for regulating pathological angiogenesis by controlling expression of c-Cbl in endothelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Antibodies.

Recombinant human M-CSF-1 was purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies, PY-20 and 4G10 were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) and Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY), respectively. The following antibodies were also purchased from Upstate Biotechnology: Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 (pY1052), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 (pY1057), and mouse monoclonal anti-c-Cbl clone 7G10 (used for both immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting). Mouse monoclonal antibody to ubiquitylated proteins (IgG1; clone FK2) was purchased from Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies: anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 (pY1052/pY1057) and anti-phospho-PLCγ1 (pY783) were purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). The following antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA): Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-c-Cbl (pY731) and (pY774), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-VEGFR-2 (pY1173) (clone 19A10), and mouse monoclonal anti-HA (clone 6E2). Mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-c-Cbl (pY700) was purchased from PharMingen (La Jolla, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-PLCγ1 used for both immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as well as mouse monoclonal anti-Cbl-b (G-1; sc-8006) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGFR-2 sera were raised against either the VEGFR-2 kinase insert domain (1410) or VEGFR-2 C terminus (1412) (10, 12).

Cell Lines and Constructs.

Ectopic expression of either CKR alone or with HA-tagged wild-type c-Cbl and 70Z/3-Cbl in PAE cells has been described (10, 12). Expression of tyrosine mutant VEGFR-2 chimeras in PAE cells has been described (4, 10). pMSCVpuro retroviral constructs containing human cDNA sequences encoding HA-tagged C3HC4C5-Cbl or HA-tagged Cbl-N (encoding Cbl residues 1–357) as well as the pJZenNeo/G306E/70Z/3-Cbl retroviral expression construct have been described (11). The influenza virus HA-tagged bovine PLCγ1, containing an N-terminal myristoylation and palmitoylation motif from the human Fyn sequence (Palm-PLCγ1-HA), in the expression vector pCIneo (Promega, Madison, WI) has been described (15) and was kindly provided by Ezio Bonvini (Laboratory of Immunobiology, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Knockdown of endogenous c-Cbl expression in PAE cells was achieved through retroviral transduction using the pSUPER.retro.puro vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA). The sense oligonucleotide insert used to produce c-Cbl shRNA transcripts was 5′-CCGCTTTGGATTGGTTTGA-3′ and 5′-AAGAGCATCTCCACCTCTA-3′ for scrambled shRNA transcripts.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

The cDNA of the VEGFR-2 chimera (CKR) was used as a template to generate the mutants: F1052/CKR and F1057/CKR. Creation of the VEGFR-2 chimera (CKR), in which the extracellular domain of VEGFR-2 is replaced with that of the human CSF-1R, has been described (10). The mutations were created by using a PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method as described (4, 10).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting Analysis.

Equal numbers of cells from the indicated PAE cell lines were grown until 80–90% confluent. After serum starvation, cells were left either resting or stimulated with 40 ng/ml CSF-1 at 37°C as indicated in the figure legends. Cells were prepared and lysed as described (12). For analysis of ubiquitylated proteins cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer, normalized whole cell lysates were subject to immunoprecipitation by incubating with appropriate antibodies.

In vitro GST fusion protein binding experiments.

Equal numbers of cells from the indicated PAE cell lines were grown to 90% confluency before serum starvation for 16 h. Unstimulated or CSF-1-stimulated cells were lysed in ice-cold EB supplemented with 2 mM Na3VO4 and a protease inhibitor mixture. Equal amounts of the appropriate immobilized GST fusion proteins were incubated with normalized whole cell lysates by gentle rocking for 3 h at 4°C. The beads were washed four times in the presence of protease inhibitors and Na3VO4, and proteins were eluted as described (12).

Dot blot assay.

Purified recombinant GST or GST-Cbl-N (TKB) were eluted from glutathione-Sepharose beads, and protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford method. Varying amounts of the fusion proteins were then dot blotted onto a PVDF membrane using a Minifold 1 microsample filtration manifold (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). After blocking, the membrane was probed with synthesized VEGFR-2-derived peptide containing Y1052 and Y1057 in the phosphorylated state (10 μg/ml). The membrane was then processed for immunoblotting as described (12).

In vitro angiogenesis/tubulogenesis assay.

Endothelial cell spheroids were generated as described (4, 23, 24).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants EY0137061 and EY012997 and Massachusetts Lions Eye research Fund (to N.R.) and NIH Grants CA 87986, CA99900, and CA99163 (to H.B.).

Abbreviations

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

- PAE cell

porcine aortic endothelial cell.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700809104/DC1.

References

- 1.Jain R. Nat Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahimi N. Front Biosci. 2006;11:818–829. doi: 10.2741/1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. EMBO J. 2001;20:2768–2778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer RD, Latz C, Rahimi N. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16347–16355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300259200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai Y, Ohgimoto K, Kataoka Y, Yoshida N, Shibuya M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1076–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji Q-S, Winnier GE, Niswender KD, Horstman D, Wisdom R, Magnusen MA, Carpenter G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2999–3003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao H-J, Kume T, McKay C, Xu M-J, Ihle JN, Carpenter G. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9335–9341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson ND, Mugford JW, Diamond BA, Weinstein BM. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1346–1351. doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HK, Kim JW, Zilberstein A, Morgolis B, Kim JG, Schlessinger J, Rhee SG. Cell. 1991;65:435–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahimi N, Dayanir V, Lashkari K. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16986–16992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ota S, Hazeki K, Rao N, Lupher ML, Jr, Andoniou CE, Druker B, Band H. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:414–422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AJ, Meyer RD, Band H, Rahimi N. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2106–2118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thien CBF, Langdon WY. Biochem J. 2005;391:153–165. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon CH, Lee J, Jongeward GD, Sternberg PW. Science. 1995;269:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.7652556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verí MC, DeBell KE, Seminario MC, Dibaldassare A, Reischl I, Rawat R, Graham L, Noviello C, Rellahan BL, Miscia S, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6939–6950. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6939-6950.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupher ML, Jr, Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Cantley LC, Band H. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33140–33144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyun-Choi J, Bae S, Park J, Ha S, Song H, Kim J-H, Cocco L, Ryu S, Suh P-G. Mol Cells. 2003;15:245–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayanir V, Meyer RD, Lashkari K, Rahimi N. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32714–32719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmqvist K, Cross MJ, Rolny C, Hagerkvist R, Rahimi N, Matsumoto T, Claesson-Welsh L, Welsh M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22267–22275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igarashi K, Shigeta K, Isohara T, Yamano T, Uno I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:77–82. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratcliffe KE, Tao Q, Yavuz B, Stoletov K, Spring SC, Terman BI. Oncogene. 2002;21:6307–6316. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC. Nature. 1995;376:62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer RD, Mohammadi M, Rahimi N. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:867–875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer RD, Singh AJ, Rahimi N. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:735–742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305575200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.