Abstract

The development of new genetic systems for studying the complex regulatory events that occur within Borrelia burgdorferi is an important goal of contemporary Lyme disease research. Although recent advancements have been made in the genetic manipulation of B. burgdorferi, there still remains a paucity of basic molecular systems for assessing differential gene expression in this pathogen. Herein, we describe the adaptation of two powerful genetic tools for use in B. burgdorferi. The first is a Photinus pyralis firefly luciferase gene reporter that was codon optimized to enhance translation in B. burgdorferi. Using this modified reporter, we demonstrated an increase in luciferase expression when B. burgdorferi transformed with a shuttle vector encoding the outer surface protein C (OspC) promoter fused to the luciferase reporter was cultivated in the presence of fresh rabbit blood. The second is a lac operator/repressor system that was optimized to achieve the tightest degree of regulation. Using the aforementioned luciferase reporter, we assessed the kinetics and maximal level of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-dependent gene expression. This lac-inducible expression system also was used to express the gene carried on lp25 required for borrelial persistence in ticks (bptA). These advancements should be generally applicable for assessing further the regulation of other genes potentially involved in virulence expression by B. burgdorferi.

The zoonotic life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, is complex, involving both an arthropod tick (Ixodes scapularis) vector and a mammalian host (68). The ability of B. burgdorferi to occupy these two very diverse niches is governed by a complex regulatory shift that dramatically alters the expression of major outer surface proteins (Osps) (3, 25, 27, 28, 33, 37, 50, 56, 63, 64, 73). By far the best-characterized example of this coordinated response is the reciprocal regulation of OspA and OspC in response to certain environmental signals (e.g., pH, cell density, temperature, or blood) (18, 19, 57, 59, 64, 77, 79). OspC is preferentially expressed when exposed to conditions akin to those that the bacterium might encounter in the midgut of a feeding tick or a mammalian host. Although there is some discrepancy regarding the precise role of OspC in the infectious cycle of B. burgdorferi, studies agree that OspC is required for the early events contributing to the transition of the bacterium into the mammalian host (40, 53, 72, 76).

Targeted gene disruption studies have led to the discovery of the RpoN/RpoS alternative sigma factor regulatory pathway (16, 34, 42, 83), responsible for modulating key adaptive responses involved in the transition of B. burgdorferi from the tick to the mammal. RpoN, in concert with the response regulator Rrp2 (82), activates the transcription of the alternative sigma factor gene, rpoS. RpoS, in turn, activates the transcription of OspC, a member of the group I-regulated lipoproteins (42, 79). RpoS may also function to repress ospA expression, albeit through an unknown mechanism (15).

At the present time, the choices for available reporter systems that are suitable for assessing the regulation of selected genes in B. burgdorferi are limited. Gene reporter studies, employing primarily green fluorescent protein (gfp)-based systems (15, 16, 20, 31, 32), have been used for elucidating the regulatory events governing the expression of OspA, OspC, and other members of the group I lipoproteins, particularly in response to RpoS activation. To date, only one additional gene reporter system, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat), has been utilized in B. burgdorferi (2, 66, 67). Unfortunately, these studies utilized a vector that is inherently unstable in B. burgdorferi, therefore resulting in only transient expression of cat. Another disadvantage of the cat reporter system is that assays for measuring cat expression are rather laborious (e.g., enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, thin-layer chromatography, radioactive/fluor diffusion, or real-time PCR). One of the more popular bioluminescent reporters currently being utilized for gene expression studies in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes is based on Photinus pyralis firefly luciferase (luc) (1, 29, 38, 69). The level of luciferase in a cell lysate is conveniently quantitated using a luminometer that measures the light produced as luciferase catalyzes the oxidation of the luciferin reagent; the entire process from harvesting cells to expression analysis requires a maximum of 30 min. It is this relative ease and speed by which a luciferase assay can be performed, combined with the overall high sensitivity of the assay, that make a luc-based reporter system a preferable alternative to those employing gfp or cat. For these reasons, we sought to determine whether luciferase could be used as a transcriptional gene reporter in B. burgdorferi.

An inherent potential difficulty in utilizing all reporter systems in B. burgdorferi lies in the codon usage by this bacterium (60). Because B. burgdorferi has a GC content of only 28.6%, the codon bias for borrelial genes is shifted towards AT-rich codons (36). This bias compromises the translation of reporter genes developed for organisms with a higher GC content (e.g., Escherichia coli lacZ [GenBank accession NC_000913], 56.3% GC; or P. pyralis luc [GenBank accession U47122.2], 46.8%), thereby potentially making reporter activity an inaccurate representation of transcriptional activity. Herein, we sought to adapt a P. pyralis firefly luc reporter for use in differential gene expression analyses in B. burgdorferi, with an emphasis on modifying the codon bias of the luc gene to better match that of B. burgdorferi.

Another genetic tool that has been unavailable to Borrelia researchers is an inducible expression system. Inducible systems, such as the lac operator/repressor and tet operator/repressor, were originally derived from E. coli (9, 10, 41), but have been utilized in numerous bacterial species with full functionality (24, 43-45, 52, 74, 85). The development of inducible expression systems will serve to advance the borrelial field, as it will allow researchers to perform a multitude of experiments, including the generation of conditional lethal mutants (44, 45, 52, 74) and the ectopic expression of putative virulence/regulatory factors (24, 43, 52). To this end, Cabello et al. (14) described the first inducible expression system, based on the E. coli Tn10 tet operon, for B. burgdorferi. To further expand the genetic armamentarium available to Borrelia researchers, we have adapted the lac operator/repressor system for application in B. burgdorferi. The relative simplicity of the lac-inducible system makes it ideally suited to application in B. burgdorferi (9, 10). For full function, this system requires only a constitutively expressed repressor (LacI), a promoter sequence containing a LacI-binding site (operator), and a suitable inducer, such as isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). In the present study, we demonstrate the first application of the IPTG-inducible lac repressor/operator system to B. burgdorferi genetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli strains XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used as cloning hosts. Transformation of B. burgdorferi was carried out as described by Yang et al. (84). BptA inducible expression experiments employed the previously characterized bptA::aadA insertion mutant, BbDTR596 (Table 1) (58). BbDTR630 (Table 1) was utilized for borrelial expression experiments to characterize the luciferase reporter and lac inducible expression system. BbDTR630, which carries an aph[3′]-IIIa aminoglycoside resistance gene on the virulence-associated plasmid lp25 (39, 54, 55, 78), was generated from an isolate of the infectious, nonclonal strain 297 designated PL133 (Table 1) (58). The integration of the selectable marker was achieved by first amplifying aph[3′]-IIIa from pMS2 (Table 1) (62) using Takara Ex-Taq polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Japan) and the primers aph-IIIa 5′-AscI and aph-IIIa 3′-AscI (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which also incorporated AscI restriction sites into the 5′ and 3′ ends of the resistance marker. The AscI-flanked resistance marker then was subcloned into pDTR627 (Table 1) (58), a suicide vector carrying a 3.7-kb region of lp25 with a unique AscI restriction site (engineered 40 bp downstream of the pncA/bbe22 gene). The resulting construct, pDTR630 (Table 1), then was transformed into PL133 to generate BbDTR630. Phenotypic analyses revealed that BbDTR630 exhibited in vitro growth characteristics and OspA/OspC regulatory patterns indistinguishable from wild-type PL133 (79). Furthermore, when the infectivity of BbDTR630 was assessed using the murine (needle-challenge) model of Lyme borreliosis (7, 8), there was no change in 50% infective dose (ID50) values relative to the PL133 parent (data not shown). For luciferase reporter validation studies, B. burgdorferi clones were cultured in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelley II (BSK-II) medium (6). BSK-H incomplete medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR) was used for experiments characterizing the inducible expression system. Kanamycin (Kan) at a final concentration of 160 μg/ml was included in BSK medium for the selection of Kanr transformants. To select for streptomycin-resistant (Strepr) transformants, streptomycin was added to cultures at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Cell culture density was assessed by enumerating spirochetes using dark-field microscopy. To ensure accuracy of density determination, triplicate counts were performed on culture samples.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15::Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| B. burgdorferi | ||

| PL133 | Transformable, nonclonal, infectious derivative of strain 297 | 58 |

| BbDTR630 | Infectious, clonal derivative of PL133, lp25::aph[3′]-IIIa; Kanr | This study |

| BbDTR596 | Infectious, clonal BptA mutant of PL133, bptA::aadA; Strepr | 58 |

| BbJSB66 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB66; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB82 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB82; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB161 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB161; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB165 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB165; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB175 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB175; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB56 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB56; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB70 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB70; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB104 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB104; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB252 | BbDTR630 transformed with pJSB252; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| BbJSB194 | BbDTR596 transformed with pJSB194; Strepr Kanr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T easy | TA cloning vector; Ampr | Promega |

| pMS2 | B. burgdorferi/E. coli shuttle vector with aph[3′]-IIIa; Kanr | 62 |

| pDTR627 | pGEM-T Easy::lp25 region with AscI; Ampr | 58 |

| pDTR630 | pDTR627::AscI-aph[3′]-IIIa-AscI; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pKFSS1 | B. burgdorferi/E. coli shuttle vector with PflgB-aadA; Spec/Strepr | 35 |

| pJD1 | pKFSS1 with minimal PflgB-aadA region; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJD7 | pJD1 with Plac excised and terminator inserted; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pSP-luc+ | Luciferase gene reporter construct; Ampr | Promega |

| pJSB80 | pGEM-T Easy::Bbluc+ (codon-optimized SPluc+); Ampr | This study |

| pJSB66 | pJD7::PflaB-SPluc+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB82 | pJD7::PflaB-Bbluc+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJD44 | pJD7-based shuttle vector with aph[3′]-IIIa; Kanr | 58 |

| pJD48 | pJD44::promoterless lucBb+; Kanr | This study |

| pJSB161 | pJD7::divergently oriented promoterless lucBb+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB165 | pJD7::divergently oriented PospC-Bbluc+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB175 | pJD7::divergently oriented PflaB-Bbluc+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pQE-30 | Expression vector with lac-inducible T5 promoter; Ampr | QIAGEN |

| pJSB91 | pGEM-T Easy::PpQE30 promoter region; Ampr | This study |

| pJSB92 | pGEM-T Easy::PpQE30-Bbluc+; Ampr | This study |

| pJSB70 | pJD7::PpQE30-Bbluc+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pET-11a | Expression vector with T7 tag and lacIq; Ampr | Novagen |

| pJSB104 | pJD7::PpQE30-Bbluc+ and PflaB-BblacI (tandem); Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB252 | pJD7::PpQE30-Bbluc+ and PflaB-BblacI (divergent); Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB56 | pJD7::promoterless lucBb+; Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pDTR644 | pJD44::bbe17pro:bptA (BglII-HindIII); Kanr | 58 |

| pJSB184 | pGEM-T easy::PpQE30-bptA; Ampr | This study |

| pJSB186 | pJD7::PpQE30-bptA and PflaB-BblacI (tandem); Spec/Strepr | This study |

| pJSB194 | pJD44::PpQE30-bptA and PflaB-BblacI (tandem); Kanr | This study |

Modification of pKFSS1 shuttle vector.

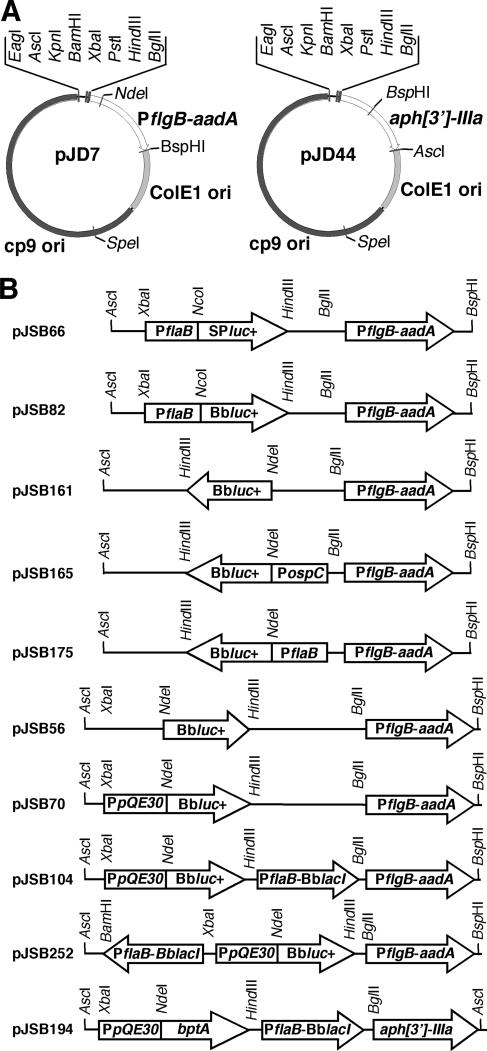

The existing cp9-based B. burgdorferi shuttle vectors, pBSV2 (71) and pKFSS1 (35) (Table 1), contain an unnecessary zeocin resistance marker that, with its flanking sequence, increases the size of the shuttle vector approximately 1 kb. To remove this extraneous DNA, the spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance marker (PflgB-aadA) of pKFSS1 first was amplified by PCR with primers FlgBprom-HindIII-5′ and FlgB/aadA-BspHI-3′ (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and TA-cloned into pGEM-T easy (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Following confirmation of the TA clones, pKFSS1 was digested with HindIII and BspHI and the shortened PflgB-aadA was substituted for the original PflgB-aadA and flanking zeocin resistance marker to generate pJD1 (Table 1). pKFSS1 and pBSV2 also contain two promoter sequences that could confound promoter/gene reporter analyses. The first promoter sequence is Plac, which was originally derived from the Plac/LacZ/MCS region of pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen). The second promoter is located in the borrelial plasmid origin of replication. This promoter is upstream of the truncated BBC12 open reading frame (ORF) and overlaps with one of the highly conserved inverted repeats flanking the BBC01-to-BBC03 gene cluster (21, 30, 36, 71). Because the precise function of these inverted repeats is not fully understood, mutation of the putative promoter elements was a less-favored approach. Therefore, an alternative approach of introducing a transcriptional terminator upstream of the shuttle vector MCS was employed. A 253-bp fragment of the MCS, Plac, was excised from pJD1 (Table 1) by digestion with EagI and KpnI. A Rho-independent intrinsic transcriptional terminator, designed from the sequence of cp8.3 (30) and the consensus of Lesnik et al. (46), then was generated by annealing four complementary oligonucleotides; Bb term frag #1, Bb term frag #2, Bb term frag #3, and Bb term frag #4 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The annealed product possessed overhangs capable of ligating to pJD1 digested with EagI and KpnI. The resulting plasmid was designated pJD7 (Table 1 and Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Diagram illustrating the two B. burgdorferi shuttle plasmids used in this study (A) and the relevant regions and restriction sites of derivative constructs generated and transformed into B. burgdorferi (B). pJSB66 and pJSB82 were used to assess the impact of codon optimization on luciferase expression. pJSB161, pJSB165, and pJSB175 were created for the lucBb+ reporter (indicated as Bbluc+on the figure) validation studies. pJSB56, pJSB70, pJSB104, and pJSB252 were generated for the development and evaluation of a lac repressor/operator system optimized for use in B. burgdorferi. pJSB194 was used to express the BptA protein under the control of the lac-inducible expression system. SPluc+, lucSp+.

Codon adaptation of Photinus pyralis firefly luciferase from pSP-luc+.

Codon optimization of the luciferase ORF from the pSP-luc+ reporter (Table 1) (Promega) was achieved using gene building technology. The DNAbuilder program (Preston Hunter and Stephen Albert Johnston, Center for Innovations in Medicine, Arizona State University; www.biodesign.asu.edu) converted the amino acid sequence for the luciferase ORF of pSP-luc+ (lucSp+) to a DNA sequence using the codon usage parameters for B. burgdorferi at http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon (49). Overlapping (20 bp) 50-mer oligonucleotides then were synthesized from the optimized DNA sequence (Midland Certified Reagent Co., Midland, TX), and the gene was constructed using the assembly PCR technique (70). Briefly, the oligonucleotides were reconstituted to a concentration of 100 μM, pooled, and then diluted to a final concentration of 25 μM. This oligonucleotide pool served as the template in the primary assembly PCR. A second PCR containing only the 5′- and 3′-terminal oligonucleotides and an aliquot of the first round of PCR then was performed to amplify the full-length gene product. The resulting PCR product was gel purified and ligated into pGEM-T Easy. Transformants were verified by restriction digest and DNA sequence analysis. The confirmed plasmid was designated pJSB80 (Table 1). A list of the oligonucleotides used for the PCR assembly reaction is provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

To assess the impact of codon optimization, the pre- and postadapted luc genes, lucSp+ and lucBb+, respectively, were fused to the promoter of the constitutively expressed flagellar core protein FlaB (PflaB) and ligated into pJD7. To achieve this, a 251-bp fragment of DNA containing PflaB first was PCR amplified from B. burgdorferi PL133 using the primers flaBpro5′-XbaI and flaBpro3′-NcoI-2nd (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy. Next, the lucSp+ ORF was PCR amplified from pSP-luc+ using the primers 5′luciferase-2nd and 3′ luciferase (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). PflaB and the corresponding luc ORFs then were excised from pGEM-T easy by digestion with XbaI/NcoI and NcoI/HindIII, respectively, and ligated into pJD7 that was linearized by digestion with XbaI and HindIII. The resulting clones were verified by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. pJD7::PflaB-SPluc+ and pJD7::PflaB-Bbluc+ are designated herein as pJSB66 and pJSB82 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), respectively. pJSB66 and pJSB82 were transformed into BbDTR630, to generate BbJSB66 and BbJSB82 (Table 1). To confirm Strepr transformants, DNA was isolated from Borrelia clones using the Wizard Plus SV mini-prep kit (Promega) and transformed into E. coli. Plasmid DNA was isolated from the resulting E. coli clones and verified by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis.

To assess codon optimization, BbJSB66 and BbJSB82 were inoculated into BSK-H medium containing Strep selection from frozen stocks stored at −70°C. Once these cultures grew to an adequate density (∼1 × 107 spirochetes/ml), they were used to inoculate fresh BSK-H medium, also containing Strep, to a density of 1 × 103 cells/ml. These cultures were grown for approximately 3 days to a cell density of between 0.5 × 106 and 5 × 106 spirochetes/ml, at which time four 1-ml aliquots of each culture were transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and the spirochetes were collected by centrifugation (10 min at 10,000 × g). The medium was aspirated, and pellets were retained for luciferase assays.

Luciferase assays.

A commercial luciferase assay system (Promega) was used in this study. Lysates were prepared by resuspending Borrelia cell pellets in 100 μl of cell culture lysis mixture containing 25 mM Tris-phosphate (pH 7.8), 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.125% lysozyme, and 0.25% bovine serum albumin. Next, the cell suspension was thoroughly mixed by vortexing for 1 min. Ten microliters of lysate was aliquoted into a black 96-well assay plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), and immediately prior to beginning measurements, 50 μl of luciferase assay reagent was added to each well. The reactions were mixed by agitating the plate for 5 s, after which the luciferase activity in each well was measured for 1 s using a Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN). Measurements are reported as relative luciferase units (RLU) with average background luminescence subtracted from the readings. Unless otherwise noted, results are presented as the RLU/1 × 105 spirochetes.

Generation of luciferase reporter constructs for validation experiments.

To validate the luciferase reporter, two promoters were fused to the lucBb+ ORF. Due to restriction site incompatibility, the promoter-reporter fusions could not be assembled directly in pJD7. Therefore, a shuttle vector carrying the promoterless lucBb+ ORF (pJD48; Table 1) was generated first by ligating the HindIII/BglII fragments of pJSB80 (pGEM-T Easy::Bbluc+) and the pJD44 shuttle vector (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). A 140-bp DNA fragment containing the ospC promoter (PospC) was amplified using PL133 DNA as a template and the primer set 5′OspC up 1723-BglII and 3′ospC prom-NdeI #2 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR fragment was TA cloned into pGEM-T Easy, verified by DNA sequencing, excised with NdeI and BglII, and ligated into pJD48 digested with same restriction enzymes. Because BbDTR630 is already Kanr, it was necessary to replace the aph[3′]-IIIa cassette in the pJD44-based shuttle vectors with PflgB-aadA from pJD7. The marker replacement was achieved first by digesting pJD7, pJD48, and pJD48-PospC with SpeI and BglII to excise a fragment containing the relevant marker. The pJD7-derived PflgB-aadA fragment then was ligated into pJD48 and pJD48-PospC to construct pJSB161 and pJSB165 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), respectively. The flaB promoter for the positive control PflaB-Bbluc+ was isolated from pJSB82 (pJD7::PflaB-Bbluc+) digested with BamHI and NdeI. The fragment encoding the promoterless lucBb+ was excised from pJD48 by digesting with NdeI and SpeI, and, as before, PflgB-aadA was derived from the BglII/SpeI fragment of pJD7. These fragments then were ligated to create pJSB175 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). Note that in these plasmids, the lucBb+ reporter and resistance marker are divergently oriented to prevent transcriptional readthrough from upstream genes. The B. burgdorferi clones recovered after electroporation of BbDTR630 with pJSB161, pJSB165, or pJSB175 were designated BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175 (Table 1), respectively. To verify Strepr clones, DNA was isolated from Borrelia transformants and electroporated into E. coli. Plasmid DNA was isolated from the resulting E. coli clones and characterized by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis.

To validate the luc reporter, the influence of blood supplementation (77) on the expression of luciferase was assessed in cultures of BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175. BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175 were inoculated from frozen stocks stored at −70°C into BSK-II medium supplemented with Strep. When these cultures grew to the appropriate density (approximately 1 × 107 spirochetes/ml), they were used to inoculate 40 ml of fresh BSK-II medium, also containing Strep, to a dilution of 1 × 103 spirochetes/ml. After cultures reached a density between 0.3 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells/ml, they were divided. One culture was treated with 6% fresh heparinized rabbit blood (10 ml BD sodium heparin Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) with the buffy coat extracted, while the second culture was treated with 6% heparin-supplemented BSK-II (∼14 USP/ml). Cultures were grown for 2 days with intermittent mixing to resuspend the red blood cells (RBCs). At 2 days posttreatment, the cell density for each was determined and four 1-ml aliquots were collected. Immediately prior to processing, 6% whole blood was added to the aliquots of the culture grown in the absence of blood; hemoglobin released from RBCs during lysate preparation quenches the luminescence signal, thereby skewing the readings (22, 65). RBCs and bacterial cells then were collected by centrifugation (10 min at 10,000 x g), lysed, and luciferase assays were performed as described above. The remaining portion of the culture was processed for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis (see below).

qRT-PCR analysis.

Cultures of BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175 cells were grown and treated as described above. Immediately prior to centrifugation of cultures to collect cells, 6% whole blood was added to the cultures grown in the absence of blood to standardize purification. To prevent RNase-dependent mRNA degradation, a 1/10 volume of chilled 5% water-saturated phenol (pH <7.0) in ethanol was added to each culture. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C prior to processing. Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets using Trizol (Invitrogen), as per the manufacturer's instructions, purified from the Trizol-extracted aqueous phase using RNeasy mini columns (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA). Purified RNA then was treated with DNase, and RNA integrity was determined on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA); RNA integrity numbers were >8 for all samples. Relative levels of ospC, lucBb+, and flaB transcripts were determined using the Applied Biosystems 7500 reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) system and SYBR Green one-step qRT-PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primer sets (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) ospCF391 and ospCR479, lucF607 and lucR688, and flaBF9 and flaBR82 were used for ospC, lucBb+, and flaB, respectively. Twenty-five nanograms of RNA was added per 25-μl reaction mixture with six replicates represented per sample. Each reaction contained 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 μl of each primer (2.5 mM), and 0.125 μl Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (50 U/μl; Applied Biosystems). The run protocol consisted of a reverse transcription step (30 min at 48°C), a denaturation step (10 min at 95°C), and a 40-cycle quantitation program (15 s at 95°C, 60 s at 60°C). The results of two independent sets of cultures are reported in the Results. Because the amplification efficiencies of the reference (flaB) and the unknowns (ospC and lucBb+) were approximately equal, the ΔΔCt method of relative transcript quantitation could be applied to these samples (Applied Biosystems 7500 system—SDS software version 1.3.1.22). Control reactions, in which reverse transcriptase was excluded, were negative for amplification.

Generation of test constructs for the borrelial lac inducible expression system.

The lac inducible promoter from pQE-30 (QIAGEN Inc.), PpQE30, was generated by annealing four complementary oligonucletides; pQE30 prom I, pQE30 prom II, pQE30 prom III, and pQE30 prom IV (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The annealed fragment contained 5′ and 3′ overhangs that were complementary to the ends generated when pJD7 was digested with XbaI and PstI. The PstI site at the 3′ end of the promoter then was exchanged for an NdeI site to allow fusion of the promoter to the lucBb+ reporter gene. This modification was achieved by PCR amplification of the promoter region in the shuttle vector with a 5′ oligonucleotide anchored upstream of PpQE30 in pJD7 and a 3′ primer that mutated the PstI site, cp9 ORF seq and pQE30 3′ NdeI (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), respectively. This NdeI-modified PpQE30 fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy to generate pJSB91 (Table 1). The lucBb+ fragment was excised from pJSB80 (pGEM-T easy::Bbluc+) by digestion with NdeI and ligated with pJSB91 also digested with NdeI. The resulting transformants were screened for proper fusion of the promoter and reporter fragments. Once a correct clone (pJSB92; Table 1) was identified, the PpQE30-Bbluc+ fusion was excised with AscI/HindIII and ligated into pJD7 that was linearized with AscI and HindIII. The resulting vector was designated pJSB70 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B).

The second requisite component required for the lac inducible expression system, a highly-expressed constitutive LacI repressor, was generated by PCR amplifying a 243-bp DNA fragment encoding the flaB promoter from PL133 using the primers 5′PflaB-HindIII and 3′PflaB-Nco/ATG (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To further enhance the expression of LacI, the lacI ORF from pET-11a (Novagen, San Diego, CA) (Table 1) was codon adapted using the gene-building approach noted earlier. A list of the oligonucleotides synthesized for lacI codon optimization is provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material. To fuse PflaB and the gene-built LacI ORF (lacIBb), the two fragments were digested with HindIII/NcoI and BspHI/BglII and ligated into pJSB70 digested with HindIII and BglII. The resulting plasmid is referred to as pJSB104 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). To generate pJSB252 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), in which the constitutive LacI is divergently oriented upstream from the inducible lucBb+, the PflaB-BblacI was PCR amplified using pJSB104 as a template and the primer set 5′ PflaB-XbaI and 3′ BbLacI-BamHI (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy and verified by DNA sequence analysis. The PflaB-BblacI insert was excised using XbaI and BamHI and then ligated into pJSB70 linearized with the same restriction enzymes. The promoterless lucBb+ construct, pJSB56 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), was generated by ligating the XbaI/HindIII-digested lucBb+ fragment from pJSB80 and pJD7 also digested with XbaI and HindIII. The B. burgdorferi clones recovered after electroporation of BbDTR630 with pJSB56, pJSB70, pJSB104, or pJSB252 are designated BbJSB56, BbJSB70, BbJSB104, and BbJSB252, respectively (Table 1). Strepr transformants were verified by electroporation of E. coli with DNA isolated from the Borrelia transformants. Plasmid DNA was purified from the resulting E. coli clones and confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis.

For test inductions, BbJSB56, BbJSB70, BbJSB104, and BbJSB252 were inoculated into BSK-H medium containing Strep from frozen stocks stored at −70°C. Once these cultures grew to a cell density of approximately 1 × 107 spirochetes/ml, they were used to inoculate fresh BSK-H medium, also supplemented with Strep selection, to a dilution of 1 × 103 spirochetes/ml. These cultures were grown to a cell density between 0.5 × 106 and 1 × 106 cells/ml, at which time the cultures were induced with various concentrations of IPTG. At the appropriate time intervals, the cell density was determined and quadruplicate samples were processed for luciferase assays as described above (for BbJSB66 and BbJSB82).

The bptA inducible expression construct, pJSB194 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), was generated by excising the BptA ORF from pDTR644 (Table 1) (58) using NdeI/PstI and ligating it into pJSB91(pGEM-T Easy::Ppqe30 promoter) digested with NdeI and NsiI. The resulting construct, containing PpQE30 fused to the bptA ORF, was designated pJSB184 (Table 1). The PpQE30-bptA fusion was removed from pJSB184 using AscI and HindIII and combined with pJSB104 digested with the same enzymes to generate pJSB186 (Table 1). Because the BptA test induction was to be carried out in BbDTR596 (Table 1) (58), which is already Strepr, the induction cassette had to be moved into pJD44. To achieve this, the region containing the PpQE30-bptA fusion and PflaB-BblacI was removed from pJSB186 using XbaI and BglII and inserted into XbaI/BglII-digested pJD44. The resulting construct, pJSB194 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), was electroporated into BbDTR596 to generate BbJSB194 (Table 1). DNA was isolated from Kanr clones and transformed into E. coli. Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli transformants and verified by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. Inductions with BbJSB194 were carried out as detailed above (for the PpQE30-Bbluc+ studies), and culture aliquots were collected at 6 h after the addition of 1 mM IPTG for assessment by immunoblotting.

Immunoblot analyses.

BbJSB56, BbJSB70, BbJSB104, and BbJSB194 were inoculated into BSK-H medium containing Strep from frozen stocks stored at −70°C. Once these cultures grew to a density of approximately 1 × 107 spirochetes/ml, they were used to inoculate fresh BSK-H medium, also supplemented with Strep selection, to a dilution of 1 × 103 spirochetes/ml. These cultures were grown to a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml at which time the cultures were divided; one culture remained untreated, while 1 mM IPTG was added to the second. At 0, 6, and 24 h postinduction, the cell density was determined and quadruplicate samples of BbJSB56, BbJSB70, and BbJSB104 were processed for luciferase assays to confirm proper induction of lucBb+. Samples also were collected and processed for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting, as previously described (81). Immunoblots were developed using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Unless otherwise noted, a volume of whole-cell lysate equivalent to 1 × 107 spirochetes was loaded per gel lane. Luc was detected using a commercially available goat polyclonal antibody directed against recombinant luciferase (Promega). The monoclonal anti-LacI antibody from clone 9A5 was supplied by Upstate USA (Charlottesville, VA). The chicken immunoglobulin Y anti-FlaB antibody was a generous gift from Kayla Hagman (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas). The generation of the rat anti-BptA antisera was previously reported (58). The molecular mass standard, Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA) All Blue Precision Plus marker, was detected using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated StrepTactin (Bio-Rad).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences for the codon-optimized lucBb+ and lacIBb ORFs have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. EF043384 and EF043385, respectively.

RESULTS

Adaptation of Photinus pyralis firefly luciferase reporter for use in B. burgdorferi.

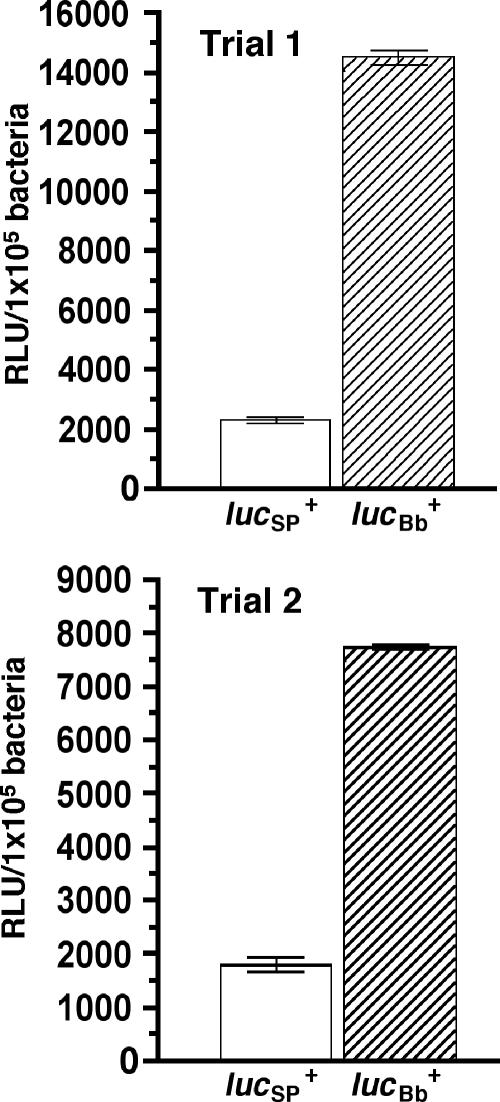

To date, there is only one gene reporter system, gfp, whose utility has been demonstrated for differential gene expression studies in B. burgdorferi (5, 13, 15, 16, 20, 31, 32, 47). Because of the limitation in the number of suitable reporter systems, we sought to identify additional transcriptional reporters (such as firefly luciferase) that might also be used in Borrelia. However, codon usage analysis of the lucSp+ gene (derived from pSP-luc+) revealed numerous codons that are significantly underutilized by B. burgdorferi (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) (36, 49). Because these “rare” codons could result in inefficient translation, it was possible that results from reporter studies obtained using the lucSp+ ORF might not accurately reflect transcriptional activity. To correct this potential expression bias, the lucSp+ ORF was codon adapted to optimize luc expression in B. burgdorferi (49, 70). Codon optimization resulted in a change in the luc gene from 46.8% GC to 35.9% GC. To assess the impact of codon optimization on luciferase expression/activity, the constitutive flaB promoter (PflaB) was fused to the codon-adapted luciferase ORF (lucBb+), ligated into the pJD7 shuttle vector (pJSB82; Fig. 1B), and transformed into BbDTR630. An analogous construct containing the lucSp+ ORF also was generated (pJSB66; Fig. 1B) and transformed into BbDTR630. The luciferase activity for the codon-optimized lucBb+ (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) ranged from four- to sixfold greater than that of the unmodified lucSp+ (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The impact of codon optimization on the expression of firefly luciferase. The PflaB promoter was fused to either the lucSp+ (pJSB66) or lucBb+ (codon-optimized, pJSB82) ORFs and the resulting clones were transformed into B. burgdorferi. After cultures had grown to a cell density of approximately 0.5 × 106 to 5 × 106 spirochetes/ml, four 1-ml aliquots of each culture were collected for luciferase assays. RLU readings were normalized according to cell density and are presented as the RLU/1 × 105 bacteria ± standard deviation. The results from two independent experiments (trials 1 and 2) are presented.

Validation of lucBb+ luciferase gene reporter.

Although the comparison between pJSB66 and pJSB82 (above) indicated that active lucBb+ was expressed in B. burgdorferi, it did not address the extent to which lucBb+ could be used to assess differential gene expression. To validate the lucBb+ reporter, PospC was fused to lucBb+ and introduced into the pJD7 shuttle vector to create pJSB165 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). A positive control construct (pJSB175; Table 1 and Fig. 1B), in which the constitutive PflaB was fused to lucBb+, also was generated. The construct pJSB161 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), which contains the promoterless lucBb+, served as a negative control. pJSB161, pJSB165, and pJSB175 were electroporated into BbDTR630 to generate BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175, respectively. Transformants were verified as described in Materials and Methods.

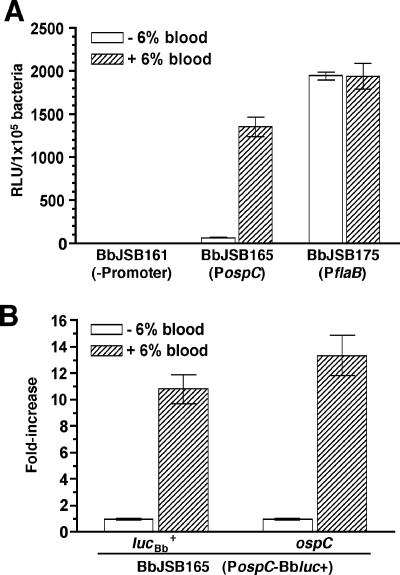

OspC is preferentially expressed in vitro when B. burgdorferi is cultured under conditions emulating those that the spirochete might encounter in the mammalian host or the midgut of a feeding tick (18, 19, 57, 59, 64, 77, 79). For instance, Yang et al. (79) demonstrated that elevated temperature, decreased pH, and increased cell density act in concert to enhance ospC expression. Unfortunately, the impact of these modified culture conditions on the relative level of OspC induction also is dependent on the formulation of the BSK medium (4, 80). An alternative approach for upregulating OspC expression, therefore, was employed (77) in which the bacteria were exposed to fresh 6% heparinized whole rabbit blood for 2 days. BbJSB161, BbJSB165, and BbJSB175 were grown, and when the cultures reached the appropriate cell density (0.3 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells/ml), they were divided. One culture was treated with heparinized blood, whereas the second culture was treated with heparin-supplemented BSK-II medium. The results from a representative trial are shown in Fig. 3A. The addition of blood resulted in an 18.5-fold increase in luciferase activity from BbJSB165, whereas blood had no effect on the activity of BbJSB175 (Fig. 3A). The average luciferase activity observed in BbJSB161 was barely above background RLU and was unaffected by blood supplementation (Fig. 3A). The data obtained with BbJSB165 indicated that ospC was consistently upregulated upon treatment of cultures with blood, as has been previously demonstrated (77). Furthermore, this increase was specific for the PospC-Bbluc+ fusion in BbJSB165, because supplementation of cultures of BbJSB161 (promoterless lucBb+) or BbJSB175 (PflaB-Bbluc+) with whole blood had no measurable effect on luciferase activity.

FIG. 3.

Influence of blood supplementation (in BSK medium) on luciferase expression driven by various B. burgdorferi promoters. Cultures of BbJSB161 (promoterless lucBb+), BbJSB165 (PospC-Bbluc+), and BbJSB175 (PflaB-Bbluc+) were treated with either 6% fresh heparinized rabbit blood (+6% blood) or with 6% heparin-supplemented BSK medium (−6% blood). Two days posttreatment, samples were removed and processed for luciferase assays. (A) Luciferase activities (RLU) from quadruplicate samples of each culture were standardized according to a cell density of 1 × 105 spirochetes, and results are presented as the mean RLU/1 × 105 bacteria ± standard deviation. (B) qRT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA extracted from the culture of BbJSB165 (PospC-Bbluc+) used for luciferase assays (above). SYBR Green one-step qRT-PCR was used to determine the relative levels of ospC, lucBb+, and flaB transcripts; flaB was included in the analyses for the purpose of signal standardization. The results from six replicate reactions are presented as the mean fold change (fold [relative to heparin-treated culture]) ± standard deviation. Two independent experiments were performed, and representative results from one trial are provided in the figure.

Although the results obtained with BbJSB165 suggested that the codon-adapted luciferase could be used for differential gene expression analyses in B. burgdorferi, it was still necessary to verify that the increase in luciferase activity after cultivation (in the presence of blood) correlated with an increase in PospC-Bbluc+ transcription. It also was necessary to determine whether the increase in PospC-Bbluc+ expression was equivalent to the increase in the expression of the native ospC gene present on circular plasmid cp26 (36). Therefore, to further validate the lucBb+ reporter, total RNA was extracted from cultures of BbJSB165 (used for luciferase assays in Fig. 3A) and qRT-PCR was performed to assess the relative levels of ospC and lucBb+ transcripts in the spirochetes cultured under the two conditions. The addition of blood resulted in a 10.8-fold and 13.4-fold upregulation in lucBb+ and ospC expression, respectively (Fig. 3B). Of note, the level of the blood-dependent increase in luciferase activity from PospC-Bbluc+ (18.5-fold protein induction; Fig. 3A) compared favorably with the induction of transcripts for lucBb+ (10.8-fold increase; Fig. 3B) or ospC (13.4-fold increase; Fig. 3B), thereby validating that the codon-adapted lucBb+ could be used as a reliable transcriptional reporter.

Development of a lac repressor/operator expression system in B. burgdorferi.

Proper regulation of the E. coli lac inducible expression requires three components: (i) the LacI repressor protein, (ii) a promoter containing LacI operator sequence(s), and (iii) an inducer (9, 10). It has been demonstrated in E. coli that LacI-dependent transcriptional repression is improved when the expression of the repressor is enhanced using a stronger promoter (17, 48). To achieve elevated levels of lacI transcription in B. burgdorferi, the highly expressed, constitutive PflaB promoter was used to drive expression of the repressor protein. Because the comparison of the codon utilization of B. burgdorferi and the lacI gene revealed substantial digression between the two usage profiles (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), the lacI ORF from pET-11a (Novagen) was codon optimized (lacIBb) to enhance the production of LacI in B. burgdorferi. Codon optimization of lacI resulted in a change from 56.2% GC to 40.5% GC. The inducible promoter chosen in this study, designated PpQE30, was derived from the phage T5 promoter (12) of the pQE30 expression construct. To maximize LacI-dependent repression, this promoter contains two lac operator (lacO) sites (11). The first of these is located between the −35 and −10 regions, whereas the 5′ end of the second site overlaps the transcriptional start. The third component necessary for proper function of the lac inducible system is an inducer. In the native E. coli lac system, the release of repression is achieved by the binding of allolactose, derived from lactose (that enters the cell via the LacY permease), to the LacI tetramer (9, 10). A synthetic alternative to allolactose is IPTG, a nonhydrolyzable inducer of the LacI repressor that is capable of crossing the membrane of numerous prokaryotes (24) and eukaryotes (75), even in the absence of the requisite LacY permease. This is relevant because there is no LacY homolog encoded within the B. burgdorferi genome (36). Preliminary studies revealed that the addition of IPTG to cultures of PL133 at concentrations as high as 100 mM, which represents a concentration 10- to 100-fold greater than that typically utilized (24, 43, 85) in induction studies, had no deleterious impact on spirochete growth (data not shown).

To test the lac inducible system, three constructs were generated in the pJD7 shuttle vector; an overview of these vectors is provided in Fig. 1B and Table 1. The first construct, pJSB56, contains only the promoterless lucBb+ ORF. The remaining two shuttle vectors, pJSB70 and pJSB104, both encode PpQE30 fused to lucBb+, but pJSB104 also contains the constitutively expressed and codon-adapted repressor PflaB-BblacI. pJSB56, pJSB70, and pJSB104 were electroporated into BbDTR630, thereby generating BbJSB56, BbJSB70, and BbJSB104 (Table 1), respectively.

Test inductions were performed by growing BbJSB104 to a density between 0.5 × 106 and 1 × 106 spirochetes/ml, at which time the cultures were supplemented with various concentrations of IPTG. This lower cell density was chosen to minimize the formation of cell clumps that can occur when borrelial cultures are grown to higher cell densities; such clumping can result in the underestimation of the bacterial cell counts via dark-field microscopy. This was important because the RLU readings obtained from the luciferase assays were standardized according to cell count. It should be pointed out, though, that inductions of BbJSB104 performed at higher initial cell densities (∼1 × 107 spirochetes/ml) yielded results similar to those described for the lower-density cultures (see below).

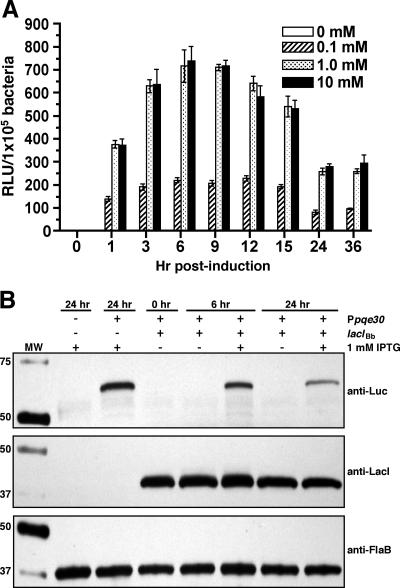

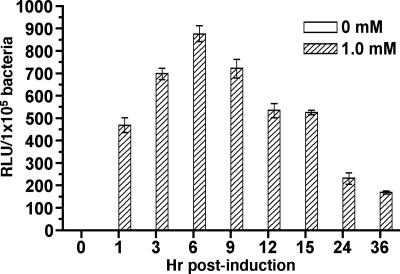

For induction experiments, samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 24, and 36 h postinduction from BbJSB104 cultures supplemented with three different concentrations of IPTG (0.1 mM, 1 mM, and 10 mM). A culture from which IPTG was excluded was included in the analysis (for an uninduced control sample). This range of IPTG concentrations was chosen so that IPTG levels that were 10-fold greater (10 mM) and 10-fold less (0.1 mM) than the concentration typically used for inducible expression studies (1 mM) could be assessed (43, 85). To measure the level of induction, samples were collected at the respective times and the luciferase activities were determined. Four independent induction experiments were performed with similar results (representative results are provided in Fig. 4A). Treatment of all cultures with IPTG induced luciferase activity, and cultures treated with 1 mM and 10 mM IPTG yielded maximal responses (Fig. 4A). The observation that 0.1 mM IPTG induced luciferase activity to only about one-third the level of what was observed for cultures treated with either 1 mM or 10 mM IPTG supported the dose dependency of IPTG treatment. In all experiments, maximal levels of luciferase induction were observed at approximately 6 to 9 h postinduction (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of luciferase induction from the Borrelia-adapted lac repressor/operator expression construct (pJSB104). Cultures of BbJSB56 (promoterless lucBb+), BbJSB70 (PpQE30-Bbluc+), and BbJSB104 (PpQE30-Bbluc+/PflaB-BblacI) were induced with various concentrations of IPTG. (A) A culture of BbJSB104 was untreated (0 mM IPTG) or induced with 0.1, 1, and 10 mM IPTG; samples were collected at the designated times postinduction (h). Luciferase activities (RLU) from quadruplicate samples of each culture were standardized according to a cell density of 1 × 105 spirochetes; results are presented as the mean RLU/1 × 105 bacteria ± standard deviation. Four independent induction studies were performed with equivalent results; data from a representative study is shown. (B) SDS-PAGE/immunoblot analysis of Luc, LacI, and FlaB using specific antibodies. Cultures of BbJSB56 (−PpQE30/−lacIBb), BbJSB70 (+PpQE30/−lacIBb), and BbJSB104 (+PpQE30/+lacIBb) were untreated or induced with 1 mM IPTG. Cells were collected at 0, 6, and 24 h postinduction. Total protein from 2 × 106 spirochetes was loaded in each gel lane for the FlaB immunoblot. FlaB detection was included to confirm that equivalent concentrations of lysates were loaded per gel lane. For gels involving Luc and LacI immunoblots, a volume of whole-cell lysate equivalent to 1 × 107 spirochetes was loaded per gel lane. Values at left denote relevant molecular masses (kDa) of Bio-Rad All Blue Precision Plus standard (MW).

Of particular interest was the observation that after 9 h of IPTG induction, luciferase activities in cultures treated with 1 or 10 mM IPTG began to decrease (Fig. 4A). The average decrease in the luciferase activities between consecutive samples collected at 3-h time intervals ranged from 9 to 19% (13.4% average) (Fig. 4A), with an overall average decrease of 62% when comparing the 9- and 24-h postinduction samples (Fig. 4A). Despite this decrease in the RLU from samples of the 1 mM and 10 mM cultures, the activity measured at 24 h postinduction (260 ± 14 RLU) was still more than 800-fold higher than the level observed in the 24-h uninduced sample (0.3 ± 0.1 RLU) (Fig. 4A). To verify that the reporter activity proportionately reflected the levels of luciferase protein present in these cells, immunoblot analyses were performed on samples from BbJSB104 treated with 1 mM IPTG for 0, 6, or 24 h (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the results for luciferase assays, there was a marked decrease in luciferase protein within the 24-h postinduction samples (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the decrease in luciferase activity (Fig. 4A) was not due to an increase in reporter protein insolubility (as luciferase reached higher concentrations in the spirochete).

The time-dependent decrease in luciferase activity observed in BbJSB104 induction could possibly be explained by the orientation of PflaB-BblacI relative to PpQE30-Bbluc+. In pJSB104, the constitutive LacI was inserted in tandem downstream of the inducible lucBb+ with minimal space and no transcriptional terminator between them. It is therefore possible that when PpQE30-Bbluc+ was induced, transcription could continue into PflaB-BblacI, thereby resulting in a polycistronic message encoding both lucBb+ and lacIBb and, thus, a concomitant upregulation of lucBb+ and lacIBb. To test this possibility, immunoblot analysis was performed to assess the levels of LacI in samples of BbJSB104 at 0, 6, and 24 h postinduction (Fig. 4B). Unlike luciferase, there was no demonstrable difference in the relative concentrations of LacI between uninduced and induced culture conditions (Fig. 4B). In addition, there was no significant change in the level of LacI between the 6- and 24-h samples (Fig. 4B). Despite the absence of a discernible increase in postinduction LacI concentrations, the role of LacI as a regulatory protein (9, 10) might suggest that minor variations in protein concentrations, which might not necessarily be evident on immunoblots, could result in more pronounced changes in gene expression.

To more precisely investigate whether the decrease in luciferase activity was the result of upregulation of LacI due to polycistronic expression of lacIBb from the lucBb+ transcript, PflaB-BblacI was repositioned in BbJSB104 from its tandem orientation (downstream of PpQE30-Bbluc+) to a location upstream and divergent from the reporter. The resulting construct, pJSB252 (Fig. 1B and Table 1), was electroporated into BbDTR630, to generate BbJSB252, and transformants were verified. A culture of BbJSB252 was grown to a density of 1 × 106 spirochetes/ml, at which time it was divided. One culture, representing the uninduced sample, was left untreated, whereas 1 mM IPTG was added to the second. These cultures were grown for 36 h with samples being harvested at 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 24, and 36 h postinduction. Two independent BbJSB252 induction studies were performed with equivalent data obtained from each of them; the results of one study are shown in Fig. 5. As was observed with BbJSB104, the maximum luciferase activity was reached at approximately 6 h postinduction, at which point it began to decrease; activity at 24 h was 27% of that measured at 6 h postinduction. Although we cannot yet definitively explain the time-dependent decline in luciferase activity in BbJSB104, these results, combined with the LacI immunoblot analysis, strongly suggest that this phenomenon is not the result of enhanced expression of the LacI repressor (due to cotranscription with the IPTG-induced lucBb+ reporter).

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of luciferase expression from the modified lac repressor/operator expression construct (pJSB252). A culture of BbJSB252 (analogous to pJSB104, but with PflaB-BblacI reoriented upstream and divergent from lucBb+) was untreated (0 mM IPTG) or induced with 1 mM IPTG. Samples were collected at the designated times (h), and luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase activities (RLU) from quadruplicate samples of each culture were standardized according to a cell density of 1 × 105 spirochetes; results are presented as the mean RLU/1 × 105 bacteria ± standard deviation. Two independent induction studies were performed with equivalent results; only data from one experiment are shown.

To assess the minimum level of repression and maximal level of induction attainable with the Borrelia-adapted lac repressor/operator system, the activities of constructs carrying either a promoterless lucBb+ (BbJSB56) or PpQE30-Bbluc+ without PflaB-BblacI (BbJSB70) were compared to uninduced and induced BbJSB104, respectively (results of two trials shown in Table 2). Cultures were grown to a density between 0.5 × 106 and 6 × 106 spirochetes/ml, at which time, they were divided and 1 mM IPTG was added to one of them. The remaining portion of culture was left untreated (uninduced sample). After 6 h of induction, samples were harvested and luciferase assays were performed. In both trials (Table 2), the luciferase activity observed in the uninduced BbJSB104 was roughly equivalent to the RLU values of the clone carrying the promoterless lucBb+ (BbJSB56), suggesting that a maximal level of repression was obtained. When the average RLU of the BbJSB70 was compared to that of the induced BbJSB104, the activity of the induced BbJSB104 was 37% of that for BbJSB70 (transformed with the construct lacking lacIBb), which was not surprising considering the high level of LacI repressor expressed in BbJSB104.

TABLE 2.

Influence of the PpQE30 promoter and lacIBb on expression of codon-optimized luciferase in B. burgdorferi

| Plasmid | Expression (RLU/105 spirochetes) with IPTG concna:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1

|

Trial 2

|

|||

| 0 mM | 1.0 mM | 0 mM | 1.0 mM | |

| Promoterless lucBb+ | 0.71 ± 0.45 | 0.25 ± 0.21 | 5.46 ± 2.95 | 7.58 ± 5.89 |

| PpQE30-Bbluc+ | 1,405.27 ± 55.01 | 1,325.93 ± 88.80 | 1,167.36 ± 37.07 | 1,044.42 ± 47.87 |

| PpQE30-Bbluc+/PflaB-BblacI | 0.93 ± 0.19 | 504.33 ± 31.62 | 1.30 ± 0.40 | 408.23 ± 12.71 |

Results (from quadruplicate samples collected at 6 h postinduction) are reported as the mean RLU/105 spirochetes ± standard deviation.

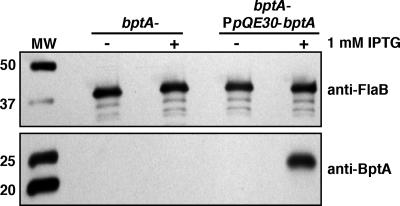

Utilization of the lac inducible system to express the B. burgdorferi BptA protein.

The bbe16 gene (36), located on the virulence-associated lp25 plasmid (39, 54, 55, 78), encodes a surface protein required for borrelial persistence in ticks (BptA) (58). Revel et al. (58) demonstrated that bptA insertion mutants of PL133 were incapable of maintaining normal spirochetal loads in the ticks, particularly in the weeks immediately following feeding. The molecular mechanism by which BptA achieves this function has yet to be elucidated. As proof of application of the lac operator/repressor system, the bptA ORF was fused to the PpQE30 promoter and introduced, along with PflaB-BblacI, into the pJD44 shuttle vector to generate pJSB194 (Fig. 1B and Table 1). This construct was electroporated into the bptA::aadA insertional mutant BbDTR596 and is referred to herein as BbJSB194. Induction assessment was performed by growing a culture of BbJSB194 to the appropriate density (0.5 × 106 to 6 × 106 spirochetes/ml), divided, and supplemented with either 1 mM IPTG or left untreated. At 6 h postinduction, the cells were collected and processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis for FlaB and BptA. A culture of similarly treated BbDTR596 was included as a negative control. The representative results from duplicate studies are shown in Fig. 6. As predicted, the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 6 h strongly induced BptA expression.

FIG. 6.

Control of BptA expression using the Borrelia-adapted lac repressor/operator expression system. Cultures of BbDTR596 (bptA-) and BbJSB194 (bptA-/PpQE30-bptA) were untreated or induced with 1 mM IPTG. Six hours postinduction, cells were collected and prepared for SDS-PAGE/immunoblot analysis; total protein from 1 × 107 spirochetes was loaded in each gel lane. Antibody against recombinant BptA was used to assess induction. Equivalent protein loading per gel lane was verified by probing for FlaB. Values at left denote relevant molecular masses (kDa) of Bio-Rad All Blue Precision Plus standard (MW). Two independent induction studies were performed with equivalent results; data from one representative experiment are shown.

DISCUSSION

Inducible expression systems, such as lac and tet repressor/operator systems (9, 10, 41), are invaluable tools in the dissection of the molecular events contributing to bacterial gene regulation and pathogenesis (24, 43-45, 74). However, no such system had been utilized in B. burgdorferi until Cabello et al. (14) described the successful application of the tet inducible system in B. burgdorferi. This system was comprised of the Tn10 TetR repressor expressed from PflaB, a hybrid borrelial promoter containing dual TetR binding sites, and the inducer anhydrotetracycline. The lac operator/repressor system (9, 10), whose simplicity is equal to that of the tet inducible system, was the focus of our current study. The first component generated was the codon-optimized LacI repressor, which was transcribed from the PflaB promoter. The increased luciferase activity observed with the codon-adapted lucBb+ reporter suggested that the expression of LacI could be maximized through the codon optimization of the LacI ORF, ultimately enhancing LacI-dependent repression (17, 48). The IPTG-inducible T5 promoter (12) derived from pQE30, then was fused to the lucBb+ reporter (PpQE30-Bbluc+), which would allow the quantitiation of induction levels obtained upon treatment of cultures with IPTG. To circumvent unfavorable codon bias, gene-building technology was employed to generate a luciferase gene that more closely matched the codon usage of B. burgdorferi. Although the results from the comparison of the pre- and postadapted reporters showed that changing the codon bias was not required for expression in B. burgdorferi, the four- to sixfold increase in luciferase activity with lucBb+ suggested that codon optimization did maximize expression by relieving some translational deficiencies.

The maximum level of PpQE30-Bbluc+ induction by IPTG occurred between 6 and 9 h postinduction, with an average 400-fold increase in luciferase activity relative to the uninduced cultures. It also was determined that treatment of cultures with 1 mM IPTG, a concentration typically used for inducible expression studies (43, 85), resulted in luciferase activity equivalent to activities obtained from cultures treated with a 10-fold higher concentration of IPTG. Because B. burgdoreri lacks an apparent LacY (permease), it remains unknown how extracellular and intracellular concentrations of IPTG potentially correlate; as such, the utility of IPTG induction remains empirical at this time. Although the observation that the luciferase activity in the cultures containing 1 and 10 mM IPTG began to decrease after 9 h of induction was unexpected, it should be noted that the activities measured in the induced 24-h samples were still over 800-fold greater than that of the corresponding 24-h uninduced culture.

Because there was no transcriptional terminator inserted between the 3′ end of lucBb+ and the 5′ end of lacIBb in this vector, it initially was suspected that the decrease in luciferase activity over time could have been due to an increase in LacIBb expression as a result of read-through from the lucBb+ transcript; LacIBb was downstream of the inducible lucBb+ in pJSB104. However, immunoblot analysis revealed no significant changes in postinduction levels of LacI and the analogous pJSB252 construct, in which the repressor was reoriented upstream and divergent from lucBb+, showed the same decrease in luciferase activity between 6 and 9 h postinduction. To address the possibility that this decrease was due to inactivation of the IPTG during the induction, BbJSB104 cultures initially treated with 1 mM IPTG were supplemented with 10 and 100 mM IPTG at 12 or 24 h postinduction. There was no increase in luciferase activity at 3, 6, or 12 h following the secondary induction with fresh IPTG (data not shown), thereby suggesting that the decrease in luciferase activity was not a function of declining IPTG concentrations. Another possible explanation for the decline in luciferase activity could be related to the reduced biosynthetic capabilities of B. burgdorferi (23, 36). Upon the treatment of BbJSB104 with IPTG, the overexpression of LucBb+ might result in the depletion of the limited intracellular stores of the requisite metabolites at a rate greater than said stores could be replenished. However, this scenario seems to be less likely because the depletion of intracellular stores would presumably have a negative impact on the growth rate and this was not found (uninduced and induced cultures grew at similar rates) (data not shown). The decrease in luciferase activity could also represent an increase in the relative insolubility of luciferase as the intracellular concentrations of the LucBb+ reaches levels that promote formation of insoluble/misfolded protein aggregates. The time-dependent loss of luciferase activity also could emanate from a disruption of protein synthesis or the activation of proteases that degrade luciferase. However, LacI and FlaB levels remained constant when luciferase concentrations declined, which argues against either a global diminution of protein synthesis or the activation of proteases. Whereas we cannot yet explain the decrease in luciferase expression over time, the collective data suggest that the induction of luciferase from the lac inducible system does not adversely affect cell viability.

The lac inducible expression system developed in this study was designed with a particular emphasis on a high level of LacI-dependent regulation. To prevent inappropriate expression in the absence of IPTG, the expression of the LacI repressor was optimized (described above) and the lac-inducible T5 promoter from pQE30 was employed. This promoter was chosen for two reasons: (i) dual lacO sites provide the highest degree of repression (11), and (ii) the sequences of the −35 and −10 regions of this promoter are also fairly divergent from the consensus sequence of a typical bacterial RpoD/σ70-dependent promoter (12). The use of a suboptimal/weak promoter ensures that only a minimal amount of transcription will occur in the event of a momentary release of LacI-dependent repression. In fact, the luciferase activities measured for BbJSB104 or BbJSB70 (both contain PpQE30-Bbluc+) induced with 1 mM IPTG were approximately 5% and 14%, respectively, of the luciferase activity of BbJSB82 (PflaB-Bbluc+) (data not shown). It should also be noted that the higher luciferase activity in BbJSB70 (lacks PflaB-BbLacI), by comparison to that induced in BbJSB104 (contains PflaB-BbLacI), might imply that that relief of repression was incomplete. This partial induction could be due to (i) an inability to obtain saturating levels of IPTG within the cell (via passive diffusion), (ii) impaired active transport from a transporter (unknown) becoming saturated with IPTG (as extracellular levels approach 1 mM), or (iii) the presence of LacI repressor at concentrations in excess of those required to occupy all lacO sites.

To validate the newly generated lucBb+ reporter for use in B. burgdorferi differential gene expression studies, two promoters were fused to lucBb+ and inserted into a borrelial shuttle vector. Employing a blood supplementation technique to activate ospC transcription (77), we were able to reproducibly demonstrate a significant increase in transcript levels (for both ospC and lucBb+) as well as luciferase activity upon the addition of blood to cultures of the clone expressing the PospC-Bbluc+ fusion (BbJSB165). Although there was some discordance between the induction of PospC-Bbluc+ and ospC (relative increase in mRNA levels for the reporter transcript [10.8-fold] was slightly less than the induction of ospC [13.4-fold]), the disparity could have been due to relative differences in the inherent mRNA stability of the two targets. Because the lucBb+ ORF is 1,649 bp in length, whereas the OspC gene is only 633 bp, it is possible that the increased size of the lucBb+ mRNA could make it more susceptible to degradation. This size difference might also affect the processivity of RNA polymerase; this would result in relatively fewer full-length copies of the longer lucBb+ transcript by comparison with the shorter ospC mRNA. Yet another possible explanation for the discrepancy in the qRT-PCR would be differences in amplification efficiency between ospC and lucBb+ during the analysis.

Comparison of ospC transcript levels and PospC luciferase activity revealed approximately equivalent increases in relative expression levels, thereby providing convincing validation of our newly developed lucBb+ reporter. There was a slight variance with respect to the increase in ospC transcript levels and the increase in luciferase activity, 13.4-fold and 18.5-fold, respectively, when the culture of BbJSB165 was supplemented with blood. This could be due to the stable accumulation of the LucBb+ protein (i.e., a higher rate of ospC transcript turnover by comparison to the reporter protein), but this represents a potential limitation that is common to most transcriptional reporter systems. Regardless of the minor inconsistency observed between the qRT-PCR and luciferase assay results, the relative complexity and reagent expense of alternative methods for measuring transcriptional changes (e.g., Northern blot analysis or qRT-PCR) makes in vitro gene reporters, such as luciferase, a more favorable alternative for comparative expression analyses.

The lp25-encoded BptA protein of B. burgdorferi was recently identified by our lab as being required for the ability of the spirochete to persist in the tick vector (58). To validate the borrelial lac repressor/operator expression system, the lucBb+ in pJSB104 was replaced with the ORF for BptA protein (to generate pJSB194). BbJSB194 was generated by transforming this construct into a bptA insertion mutant, and the expression of BptA was assessed by immunoblot analysis; induction of cultures with 1 mM IPTG resulted in significant upregulation of BptA. Unfortunately, the molecular mechanism by which BptA contributes to tick colonization still remains to be elucidated, but we now are poised to apply this controlled expression system toward further functional analysis of the role of BptA in the life cycle of B. burgdorferi.

The successful development of a lac repressor/operator system marks an advancement in B. burgdorferi molecular biology. The system described in this study is tailored for applications in which the tightest degree of regulation is desired, such as modulating the expression of a catalytically active protein (e.g., site-specific recombinase), a protein that is toxic when overexpressed, or an antisense RNA designed to inactivate an essential gene. However, this system could be modified to make it suitable for maximal expression applications by replacing the weaker pQE30-derived inducible T5 promoter with an E. coli trp/lac hybrid (tac) promoter (26). The tac promoter contains −10 and −35 sequences that are precise matches to the consensus sequence for σ70-dependent prokaryotic promoters, therefore making it a stronger promoter by comparison to T5. The spac-I promoter (85) is a Bacillus subtilis-derived lac-inducible promoter that has been applied to a wide variety of bacterial systems and has recently been modified to contain an optimized synthetic lacO site (24, 61). Another approach, which is analogous to that employed for the previously described borrelial tet-inducible system (14), involves the integration of lac operator(s) into a highly-expressed B. burgdorferi promoter. As all of the aforementioned modifications entail the use of stronger promoters to improve expression levels, this often necessitates the use of only one lacO to prevent disrupting the native −10 and −35 sequences. Therefore, to ensure that the maximal level of LacI-dependent repression is attained, it would be necessary to use lacO sites that are optimized by sequence and spatial orientation to improve their relative binding affinity for the LacI tetramer (61). In addition to enhancing the LacI binding site, it is also possible to improve the level of repression by increasing the intracellular concentration of the repressor protein (17, 48). This could be achieved by fusing the LacIBb ORF to a promoter that is stronger than PflaB, such as PflgB (51), and stably integrating the fusion into the chromosome (14) or the virulence-associated lp25 (58).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rafal Tokarz, Christian Eggers, and Melissa Caimano for assistance regarding the blood supplementation technique. We also thank David Rasko, Jason Huntley, and Jason Mock for technical advice and assistance during manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by grant AI-59062 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. J.S.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant T32-AI07520 and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32-AI058487 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 January 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam, J., and J. L. Cook. 1990. Reporter genes: application to the study of mammalian gene transcription. Anal. Biochem. 188:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alverson, J., S. F. Bundle, C. D. Sohaskey, M. C. Lybecker, and D. S. Samuels. 2003. Transcriptional regulation of the ospAB and ospC promoters from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1665-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anguita, J., S. Samanta, B. Revilla, K. Suk, S. Das, S. W. Barthold, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression in vivo and spirochete pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 68:1222-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babb, K., N. El-Hage, J. C. Miller, J. A. Carroll, and B. Stevenson. 2001. Distinct regulatory pathways control expression of Borrelia burgdorferi infection-associated OspC and Erp surface proteins. Infect. Immun. 69:4146-4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babb, K., J. D. McAlister, J. C. Miller, and B. Stevenson. 2004. Molecular characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi erp promoter/operator elements. J. Bacteriol. 186:2745-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbour, A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521-525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barthold, S. W., K. D. Moody, G. A. Terwilliger, R. O. Jacoby, and A. C. Steere. 1988. An animal model for Lyme arthritis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 539:264-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthold, S. W., D. H. Persing, A. L. Armstrong, and R. A. Peeples. 1991. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am. J. Pathol. 139:263-273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckwith, J. R. 1978. Lac: the genetic system, p. 11-30. In J. H. Miller and W. S. Reznikoff (ed.), The operon. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 10.Beckwith, J. R. 1987. The lactose operon, p. 1444-1452. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, vol. 2. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besse, M., B. von Wilcken-Bergmann, and B. Muller-Hill. 1986. Synthetic lac operator mediates repression through lac repressor when introduced upstream and downstream from lac promoter. EMBO J. 5:1377-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bujard, H., R. Gentz, M. Lanzer, D. Stueber, M. Mueller, I. Ibrahimi, M. T. Haeuptle, and B. Dobberstein. 1987. A T5 promoter-based transcription-translation system for the analysis of proteins in vitro and in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 155:416-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bykowski, T., K. Babb, K. von Lackum, S. P. Riley, S. J. Norris, and B. Stevenson. 2006. Transcriptional regulation of the Borrelia burgdorferi antigenically variable VlsE surface protein. J. Bacteriol. 188:4879-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabello, F. C., L. Dubytska, A. V. Bryksin, J. V. Bugrysheva, and H. P. Godfrey. 2006. Genetic studies of the Borrelia burgdorferi bmp gene family, p. 235-249. In N. ARW (ed.), The molecular biology of spirochetes. IOS Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 15.Caimano, M. J., C. H. Eggers, C. A. Gonzalez, and J. D. Radolf. 2005. Alternate sigma factor RpoS is required for the in vivo-specific repression of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmid lp54-borne ospA and lp6.6 genes. J. Bacteriol. 187:7845-7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caimano, M. J., C. H. Eggers, K. R. Hazlett, and J. D. Radolf. 2004. RpoS is not central to the general stress response in Borrelia burgdorferi but does control expression of one or more essential virulence determinants. Infect. Immun. 72:6433-6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calos, M. P. 1978. DNA sequence for a low-level promoter of the lac repressor gene and an ‘up’ promoter mutation. Nature 274:762-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll, J. A., R. M. Cordova, and C. F. Garon. 2000. Identification of 11 pH-regulated genes in Borrelia burgdorferi localizing to linear plasmids. Infect. Immun. 68:6677-6684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll, J. A., C. F. Garon, and T. G. Schwan. 1999. Effects of environmental pH on membrane proteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 67:3181-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll, J. A., P. E. Stewart, P. Rosa, A. F. Elias, and C. F. Garon. 2003. An enhanced GFP reporter system to monitor gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 149:1819-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casjens, S., N. Palmer, R. van Vugt, W. M. Huang, B. Stevenson, P. Rosa, R. Lathigra, G. Sutton, J. Peterson, R. J. Dodson, D. Haft, E. Hickey, M. Gwinn, O. White, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 35:490-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colin, M., S. Moritz, H. Schneider, J. Capeau, C. Coutelle, and M. C. Brahimi-Horn. 2000. Haemoglobin interferes with the ex vivo luciferase luminescence assay: consequence for detection of luciferase reporter gene expression in vivo. Gene Ther. 7:1333-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordwell, S. J. 1999. Microbial genomes and “missing” enzymes: redefining biochemical pathways. Arch. Microbiol. 172:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dancz, C. E., A. Haraga, D. A. Portnoy, and D. E. Higgins. 2002. Inducible control of virulence gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes: temporal requirement of listeriolysin O during intracellular infection. J. Bacteriol. 184:5935-5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das, S., S. W. Barthold, S. S. Giles, R. R. Montgomery, S. R. Telford III, and E. Fikrig. 1997. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J. Clin. Investig. 99:987-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Boer, H. A., L. J. Comstock, and M. Vasser. 1983. The tac promoter: a functional hybrid derived from the trp and lac promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Silva, A. M., and E. Fikrig. 1997. Arthropod- and host-specific gene expression by Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Investig. 99:377-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Silva, A. M., S. R. Telford, 3rd, L. R. Brunet, S. W. Barthold, and E. Fikrig. 1996. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J. Exp. Med. 183:271-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wet, J. R., K. V. Wood, D. R. Helinski, and M. DeLuca. 1985. Cloning of firefly luciferase cDNA and the expression of active luciferase in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:7870-7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn, J. J., S. R. Buchstein, L.-L. Butler, S. Fisenne, D. S. Polin, B. N. Lade, and B. J. Luft. 1994. Complete nucleotide sequence of a circular plasmid from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 176:2706-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eggers, C. H., M. J. Caimano, and J. D. Radolf. 2004. Analysis of promoter elements involved in the transcriptional initiation of RpoS-dependent Borrelia burgdorferi genes. J. Bacteriol. 186:7390-7402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eggers, C. H., M. J. Caimano, and J. D. Radolf. 2006. Sigma factor selectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi: RpoS recognition of the ospE/ospF/elp promoters is dependent on the sequence of the −10 region. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1859-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fikrig, E., S. W. Barthold, W. Sun, W. Feng, S. R. Telford III, and R. A. Flavell. 1997. Borrelia burgdorferi P35 and P37 proteins, expressed in vivo, elicit protective immunity. Immunity 6:531-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher, M. A., D. Grimm, A. K. Henion, A. F. Elias, P. E. Stewart, P. A. Rosa, and F. C. Gherardini. 2005. Borrelia burgdorferi σ54 is required for mammalian infection and vector transmission but not for tick colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:5162-5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]