Worldwide annually there are 1.7 million deaths from diarrheal diseases and 1.5 million deaths from respiratory infections (56). Viruses cause an estimated 60% of human infections, and most common illnesses are produced by respiratory and enteric viruses (7, 49). Unlike bacterial disease, viral illness cannot be resolved with the use of antibiotics. Prevention and management of viral disease heavily relies upon vaccines and antiviral medications (49). Both vaccines and antiviral medications are only 60% effective (39, 49). Additionally, to date there are no vaccines or antiviral drugs for most common enteric and respiratory viruses with the exception of influenza virus and hepatitis A virus (HAV). Consequently, viral disease spread is most effectively deterred by preclusion of viral infection.

Increases in population growth and mobility have enhanced pathogen transmission and intensified the difficulty of interrupting disease spread (14). Control of viral disease spread requires a clear understanding of how viruses are transmitted in the environment (27). For centuries it was assumed that infectious diseases were spread primarily by the airborne route or through direct patient contact, and the surrounding environment played little or no role in disease transmission (19, 27). Up until 1987 the Centers for Disease Control and the American Hospital Association focused on patient diagnosis due to the belief that nosocomial infections were not related to microbial contamination of surfaces (19). Over the years studies have changed the perspective on viral transmission to include a more complex multifactorial model of disease spread (27). There is now growing evidence that contaminated fomites or surfaces play a key role in the spread of viral infections (3, 7, 38, 71).

Viral transmission is dependent on interaction with the host as well as interaction with the environment (60). Viruses are probably the most common cause of infectious disease acquired indoors (7, 71). The rapid spread of viral disease in crowded indoor establishments, including schools, day care facilities, nursing homes, business offices, and hospitals, consistently facilitates disease morbidity and mortality (71). Yet, fundamental knowledge concerning the role of surfaces and objects in viral disease transmission is lacking, and further investigation is needed (52, 60, 61). The goal of this article was to use existing published literature to assess the significance of fomites in the transmission of viral disease by clarifying the role of fomites in the spread of common pathogenic respiratory and enteric viruses.

ROLE OF FOMITES IN VIRAL DISEASE TRANSMISSION

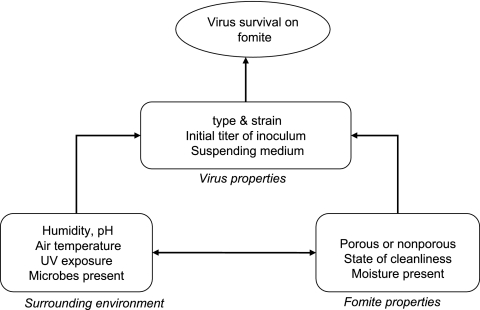

Fomites consist of both porous and nonporous surfaces or objects that can become contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms and serve as vehicles in transmission (Table 1) (24, 31, 58, 63, 66). During and after illness, viruses are shed in large numbers in body secretions, including blood, feces, urine, saliva, and nasal fluid (10, 33, 34, 39, 48, 58). Fomites become contaminated with virus by direct contact with body secretions or fluids, contact with soiled hands, contact with aerosolized virus (large droplet spread) generated via talking, sneezing, coughing, or vomiting, or contact with airborne virus that settles after disturbance of a contaminated fomite (i.e., shaking a contaminated blanket) (22, 24, 27, 58, 66). Once a fomite is contaminated, the transfer of infectious virus may readily occur between inanimate and animate objects, or vice versa, and between two separate fomites (if brought together) (27, 66). The Pancic study (52) recovered 3 to 1,800 PFU of rhinovirus from fingertips of volunteers who handled contaminated doorknobs or faucets. Using coliphage PRD-1 as a model, Rusin et al. (60) demonstrated that 65% of virus could be transferred to uncontaminated hands and 34% to the mouth. The nature and frequency of contact with contaminated surfaces vary for each person depending on age, personal habits, type of activities, personal mobility, and the level of cleanliness in the surroundings (66). Viral transfer and disease transmission is further complicated by variations in virus survival on surfaces and the release of viruses from fomites upon casual contact (24, 66). Virus survival on fomites is influenced by intrinsic factors which include fomite properties or virus characteristics and extrinsic factors, including environmental temperature, humidity, etc. (Fig. 1) (24, 66). If viruses remain viable on surfaces long enough to come in contact with a host, the virus may only need to be present in small numbers to infect the host (10, 58, 66, 71). After contact with the host is achieved, viruses can gain entry into the host systems through portals of entry or contact with the mouth, nasopharynx, and eyes (10, 24, 58, 66). Host susceptibility to viruses is influenced by previous contact with the virus and the condition of the host immune system at the time of infection (27).

TABLE 1.

Buildings and surfaces where viruses have been detected or survived

| Virus | Location of virus

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Buildings (reference[s]) | Surfaces (reference[s]) | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Hospitals (23) | Countertops, cloth gowns, rubber gloves, paper facial tissue, hands (33) |

| Rhinovirus | Not found | Skin, hands (30), door knob, faucet (52) |

| Influenza virus | Day care centers, homes, nursing home (51) | Towels, medical cart items (51) |

| Parainfluenza virus | Offices (data not published), hospitals (23) | Desks, phones, computer mouse (Boone and Gerba, submitted) |

| Coronavirus | Hospitals (23), apartment (62) | Phones, doorknobs, computer mouse, toilet handles (23), latex gloves, sponges (68) |

| Norovirus | Nursing home (6), hotels, hospital wards, cruise ships, recreational camps (22, 38, 61) | Carpets, curtains, lockers, bed covers, bed rails, drinking cup, water jug handle, lampshade (6, 38) |

| Rotavirus | Day care centers, pediatric ward (8) | Toys, phones, toilet handles, sinks, water fountains, door handles, play areas, refrigerator handles, water play tables, thermometers, play mats (8, 15, 38, 70), paper, china (2), cotton cloth, latex, glazed tile, polystyrene (1) |

| Hepatitis A virus | Hospitals, schools, institutions for mentally handicapped, animal care facilities, bar (72) | Drinking glasses (72), paper, china (2), cotton cloth, latex, glazed tile polystyrene (1) |

| Adenovirus | Bars, coffee shops (7, 24) | Drinking glasses (24), paper, china (2), cotton cloth, latex, glazed tile, polystyrene (1) |

| Astrovirus | Schools, pediatric wards, nursing homes (39) | Paper, china (2) |

FIG. 1.

Factors influencing virus survival on fomites.

There are many complex variables that influence virus survival on fomites, viral transfer from fomites, and viral infection of the host (7, 10, 24, 66). As a result, direct experimental evidence of viral transmission via fomite has been very difficult to generate due to a variety of uncontrollable variables and the unpredictability of human infection (7, 66). An example of the difficulty in producing illness in the host after exposure was indicated in the Gwaltney study using rhinovirus. Over a 10-year period, Gwaltney intranasally challenged 343 adults without rhinovirus antibodies and infected 95% of the participants (28). However, only 30% of the individuals who became infected displayed disease symptoms (28). Generally, the majority of laboratory and clinical evidence is considered indirect; however, fomite transmission data are supported by both epidemiological studies and intervention studies.

Epidemiological data indicating transmission via fomite are also difficult to evaluate (19). This difficulty stems from problems in distinguishing between different routes of transmission, such as person-to-person transmission or autoinoculation (19). Currently, laboratory studies, epidemiological evidence, and disinfection intervention studies have generated strong indirect and circumstantial evidence that supports the involvement of fomites as a vehicle in respiratory and enteric virus transmission. Studies from a variety of disciplines investigating viruses clearly support the following: (i) most respiratory and enteric viruses can survive on fomites and hands for varying lengths of time; (ii) fomites and hands can become contaminated with viruses from both natural and laboratory sources; (iii) viral transfer from fomites to hands is possible; (iv) hands come in contact with portals of entry for viral infection; and (v) disinfection of fomites and hands interrupts viral transmission (7, 24, 66).

VIRAL VIABILITY ON SURFACES

The potential for a virus to be spread via contaminated fomite depends first on the ability of the virus to maintain infectivity while on the fomite surface. Viruses are obligate parasites; therefore, the level of viral infectivity on a fomite can only decrease over time (5, 69). Several studies have demonstrated that viruses can remain infective on surfaces for different time periods (1, 2, 9, 13, 33, 48, 64, 68). The length of time a virus remains viable depends on a number of complex variables (Fig. 2). In general, UV exposure and pH have minimal effects on viral survival in indoor environments. Viral survival may increase or decrease with the number of microbes present on a surface. Increasing amounts of microbes can protect viruses from desiccation and disinfection, but deleterious effects may also result from microbial proteases and fungal enzymes (67, 69). Typically, viral presence on fomites may decrease with surface cleanliness and increase with surface usage (66). However, some cleaning products or disinfectants are ineffective against viruses and can result in viral spread or cross-contamination of surfaces (8). Easily measured and predictable factors that influence viral survival on surfaces include fomite properties, initial viral titer, virus strain, temperature, humidity, and suspending medium (66, 69).

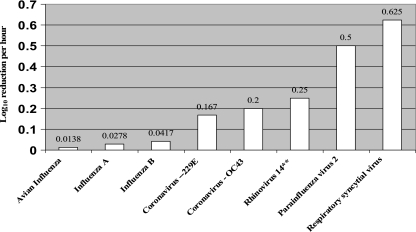

FIG. 2.

Respiratory virus inactivation rates (Ki).

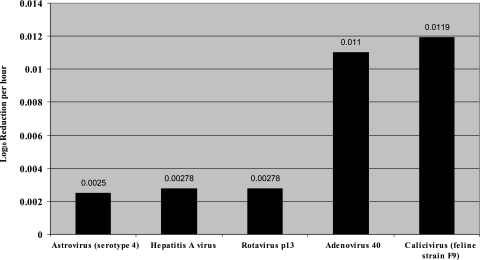

Intrinsic factors, like fomite properties, virus strain, and viral inoculation titer, consistently impact the total virus survival end point (hours, days). The majority of viruses remain viable longer on nonporous surfaces (Tables 2 and 3); however, there are exceptions (1, 27). Astrovirus survives for 90 days on porous paper but only 60 days on nonporous aluminum (2). Initial inoculation titer can prolong viral survival on environmental surfaces (66). Brady et al. (13) found that the viral survival decay rate increased with inoculum titer: a 104 virus inoculation could be detected up to 6 h longer than a 103 virus inoculation. Virus survival on fomites can also vary significantly within viral type and strain. Typically, nonenveloped enteric viruses remain viable longer on surfaces than enveloped respiratory viruses. The enteric viruses HAV, astrovirus, and rotavirus can all remain infective on surfaces for 2 months or longer (Table 3). In contrast, respiratory viruses usually remain viable for several hours to several days (Table 2). Virus inactivation rates can be expressed as the log decay of virus titer divided by the total time of viral survival. For comparative purposes, we calculated inactivation coefficients (Ki) using the following calculation after all viral titers were normalized to the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) per ml of virus: [log10 reduction (initial viral titer − final viral titer)/ml]/total hours of viral viability (64). Inactivation coefficients are linear functions and were not used to calculate T90 or T99 values, which are the times required for the initial viral titer to decrease by 90% (T90) and 99% (T99), these values were calculated using the viral survival curve, which is typically not linear. Therefore, T90 and T99 values underestimate viral survival compared to inactivation coefficients (Ki values). On nonporous surfaces, the enteric viruses reviewed typically exhibited inactivation rates at least 2 logs lower than respiratory viruses, with the exception of adenovirus and influenza virus (Fig. 2 and 3; Tables 2 and 3). Four out of five enteric viruses examined in this review produced inactivation coefficients between 0.0021 and 0.0059 log10/h, whereas four out of five respiratory viruses produced inactivation rates between 0.167 and 0.625 log10/h. The higher inactivation coefficient found among respiratory viruses indicates a faster decay rate or decreased survival on surfaces (Fig. 2 and 3). Variations in virus survival may also occur within a viral family or strain (66, 71), as seen between the 12-h survival of coronavirus 229E and the 3-h survival of coronavirus OC43 (Table 2). Consequently, variations in fomite composition, initial viral inoculation, and virus type can dramatically influence the amount of time the virus survives on a surface.

TABLE 2.

Experimental conditions for studies assaying survival of respiratory viruses on fomites

| Virus (reference) | Suspension medium | Temp (°C) | % Humidity | Fomite | Survival (h) | (Ki)a | T90 (h) | T99 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus (9) | Dulbecco's PBSb | 27.8-28.3 | 35-40 | Stainless steel | 72 | 0.0278 | 30 | 47 |

| Magazine, plastic | 48 | 0.0417 | 3 | 10 | ||||

| Pajamas, handkerchief | 24 | 0.0833 | 4 | 10 | ||||

| Influenza B virus (9) | Dulbecco's PBS | 26.7-28.9 | 55-56 | Stainless steel | 72 | 0.0417 | 12 | 37 |

| Magazine | 24 | 0.125 | <1 | 2 | ||||

| Handkerchief, tissue | 48 | 0.333 | <1 | <1 | ||||

| Avian influenza virus (73) | EMEMc with Earle's salts | Room temp | Not specified | Stainless steel | 144 | 0.0138 | 0 | 48 |

| Latex gloves | 144 | 0.0138 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Cotton | 144 | 0.0138 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Feather | 144 | 0.0138 | 24 | 48 | ||||

| Coronavirus 229E (64) | Dulbecco's PBS | 21 | 55-70 | Aluminum | 12 | 0.167 | 5.25 | 9 |

| Sterile sponges | 12 | 0.167 | 5.75 | 7 | ||||

| Latex gloves | 6 | 0.333 | 4.1 | 5.75 | ||||

| Coronavirus OC43 (64) | Dulbecco's PBS | 21 | 55-70 | Aluminum | 3 | 0.25 | 1.5 | 3 |

| Sterile sponges | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Latex gloves | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Parainfluenza virus 2 (12) | MEMd | 22 | Not specified | Stainless steel | 10 | 0.5 | 3.75 | 6 |

| Lab coat | 6 | 0.75 | NDf | ND | ||||

| Facial tissue | 2 | 1.5 | ND | ND | ||||

| Respiratory syncytial virus (33) | MEMd with pooled nasal secretions | 22.25-25.25 | 35-50 | Formica countertop | 8 | 0.625 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Countertop w/ secretions | 8 | 0.714 | 0.5 | 2.5 | ||||

| Gloves | 5 | 0.952 | 0.25 | 0.4 | ||||

| Cloth | 2.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.75 | ||||

| Rhinovirus 14 (61) | TPBe or nasal secretions | 22 | 15-25 | Steel disc w/ TPB | >25 | <0.2 | 25 | >25 |

| Steel w/ nasal discharge | >25 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 4 | ||||

| 45-55 | Steel w/ TPB | >25 | <0.2 | 25 | >25 | |||

| Steel w/ nasal discharge | >25 | 0.625 | 6 | 8 | ||||

| 75-85 | Steel w/ TPB | >25 | <0.2 | 25 | >25 | |||

| Steel w/ nasal discharge | >25 | 0.625 | 4 | 8 |

Inactivation coefficient (Ki) = log10 reduction in virus titer per ml = (initial viral titer − final viral titer)/survival (in hours) (64).

PBS, phosphate buffer solution.

EMEM, Eagle's minimal essential medium.

MEM, minimal essential medium.

TPB, tryptose phosphate broth.

ND, not done due to lack of data.

TABLE 3.

Experimental conditions for studies assaying survival of enteric viruses on fomites

| Virus (reference[s]) | Suspension medium | Fomite | Temp (°C) | % Humidity | PBS or BEMa

|

FSb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (days) | T90 (days) | T99 (days) | Kic | T90 (days) | T99 (days) | Kic | |||||

| Hepatitis A virus (1, 48) | PBS or FS | Alum.d | 4 | 85-90 | >60 | 35 | >60 | 0.00278 | 45 | >60 | 0.00278 |

| Alum. | 20 | 85-90 | >60 | 35 | >60 | 0.00278 | 35 | >60 | 0.00278 | ||

| Alum. | 20 | 45-55 | >60 | 11 | 50 | 0.00278 | 15 | 60 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 4 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | 5 | 0.00278 | <1 | 7 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | 2 | 0.00278 | <1 | 6 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 45-55 | >60 | <1 | 1 | 0.00278 | <1 | 4 | 0.00278 | ||

| Adenovirus 40 (1) | PBS or FS | Alum. | 4 | 85-90 | 15 | <1 | <1 | 0.011 | <1 | <1 | 0.00278 |

| Alum. | 20 | 85-90 | 15 | <1 | <1 | 0.011 | <1 | <1 | 0.00278 | ||

| Alum. | 20 | 45-55 | 15 | <1 | <1 | 0.011 | <1 | <1 | 0.083 | ||

| Paper | 4 | 85-90 | >30 | <1 | 1 | 0.00278 | <1 | 1 | 0.011 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 85-90 | >30 | <1 | 1 | 0.00278 | <1 | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 45-55 | >30 | <1 | 1 | 0.00278 | <1 | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| Rotavirus p13 (1) | PBS or FS | Alum. | 4 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | >60 | 0.00278 | <1 | 11 | 0.00278 |

| Alum. | 20 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | 50 | 0.00278 | 14 | >60 | 0.00278 | ||

| Alum. | 20 | 45-55 | >60 | <1 | 11 | 0.00278 | 15 | >60 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 4 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | >50 | 0.00278 | <1 | 15 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 85-90 | >60 | <1 | >60 | 0.00278 | <1 | >60 | 0.00278 | ||

| Paper | 20 | 45-55 | >60 | <1 | 2.5 | 0.00278 | <1 | 18 | 0.00278 | ||

| Astrovirus (type 4) (2) | PBS or FS | China | 4 | 85-95 | 60 | <1 | 1 | 0.0021 | 8 | 15 | 0.0021 |

| China | 20 | 7 | <1 | <1 | 0.025 | <1 | 5 | 0.025 | |||

| Paper | 4 | 90 | 5 | 15 | 0.0014 | 1 | 9 | 0.0014 | |||

| Paper | 20 | 60 | <1 | <1 | 0.0021 | <1 | <1 | 0.0138 | |||

| Feline calicivirus F9 (22) | BEM | Glass coverslip | 4 | NDe | 57 | 10 | 10 | 0.0059 | |||

| Glass | 20 | ND | 35 | <1 | 10 | 0.0119 | |||||

| Glass | 37 | ND | 7 | <1 | 1 | 0.33 | |||||

PBS, phosphate buffer solution (for all viruses except feline calicivirus F9); BEM, basal Eagle's medium (used only for feline calicivirus F9).

FS, 20% fecal suspension.

Inactivation coefficient (Ki) = log10 reduction in virus titer per ml = (initial viral titer − final viral titer)/survival (in hours) (64).

Alum., aluminum surface.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 3.

Inactivation rates (Ki) of enteric viruses.

Extrinsic environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and surrounding viral medium, have a varying effect on viral decay rate, depending on the viral strain. In the Abad et al. study (1), media changes had no noticeable effect on enteric virus survival (HAV and rotavirus); however, medium changes adversely affected the survival of adenovirus. Changes in viral suspension medium from tryptose phosphate broth to nasal discharge decreased rhinovirus survival in research by Sattar et al. (63) (Table 2). Additionally, Abad et al. (1) demonstrated that temperature and humidity variations had no effect on the survival (60 days) of HAV and rotavirus (Table 3). However, temperature variations from 4°C to 20°C decreased the survival of astrovirus (T90 change from 8 days to <24 h) and feline calicivirus (T90 change from 10 days to <24 h) (2, 21). Humidity influences the viral desiccation rate. Humidity in the United States can range from 14 to 94% in outdoor environments (76). Indoor humidity varies depending on outdoor humidity, temperature, and varying indoor factors (76). Abad et al. (1) found that decreases in humidity could negatively impact HAV, rotavirus, and adenovirus survival (Table 3). Humidity variations in the Abad et al. study (1) caused a significant decline in HAV survival (T90 change from 35 days at 85% humidity to 11 days at 45% humidity). The majority of studies investigating the effects of humidity on respiratory viruses are aerosol studies. However, Sattar et al. (64) was one of the few studies that investigated respiratory virus survival on surfaces in which humidity was used as a variable. The study found that rhinovirus exhibits optimum survival at 50% humidity (Table 2) (64).

LABORATORY EVIDENCE OF RESPIRATORY VIRUS TRANSMISSION VIA FOMITES

Several different viruses cause respiratory infections, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human parainfluenza virus (1 thru 4) (HPIV), influenza virus (A and B), human coronavirus (SARS, OC43, and 229E), rhinovirus, and adenovirus (serotypes 4 and 7) (18). It is generally accepted that respiratory viruses are spread person to person via aerosol transmission (7, 27). Nevertheless, current scientific evidence also suggests that fomites are an important vehicle in the spread of respiratory viruses (7). By using an aerosolized source, HPIV1 was found to infect only 2 of 40 children at a distance of 60 cm (37). Therefore, HPIV transmission by aerosol was considered improbable; however, transmission may have taken place by surface contamination or close contact (37). Respiratory viruses cause sneezing and coughing, which expel an estimated 107 infectious virions per ml of nasal fluid (18). Nasal secretions can travel at a velocity of over 20 m per second and a distance greater than 3 m (about 10 feet) to contaminate surrounding fomites (42, 57, 78).

Viruses have been isolated on fomites in day care centers and homes (influenza A virus) (12), offices (parainfluenza virus) (S. A. Boone and C. P. Gerba, submitted for publication), and hospitals (coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, and RSV) (23) using PCR. A hospital in Taiwan used reverse transcriptase PCR to detect coronavirus on hospital phones, doorknobs, computer mouses, and toilet handles during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (23). Studies have proven that RSV, HPIV, influenza virus, coronavirus, and rhinovirus can remain viable on fomites for several hours to several days (Tables 1 and 3) (5, 7, 9, 51). Avian influenza virus was detected on several surfaces for over 6 days (73). Studies have demonstrated that RSV, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, and rhinovirus can survive on hands for significant periods of time and that these viruses can be transferred from hands and fingers to fomites and back again (Tables 1 and 2) (5, 7, 33, 51). After a 10-second exposure, 70% of rhinovirus was transferred from donor to recipient hands in the 1978 study by Gwaltney et al. (30). Also, Gwaltney et al. demonstrated that subjects with cold symptoms had rhinovirus on their hands, and the virus was recovered from 43% of the plastic tiles they touched (30). Contaminated hands frequently come into contact with portals of entry, and so the potential for viral infection from contaminated fomites and hands exists. A study by Hendley et al. (36) found that 1 in 2.7 hospital grand round attendees rubbed their eyes and 33% picked their nose within a 1-hour observation period (36). Indirect evidence from clinical and laboratory studies clearly supports the involvement of fomites in respiratory virus infection. However, direct evidence supporting respiratory virus transmission or infection is still scarce. A study by Gwaltney et al. (29) observed that 50% of subjects developed infections after handling a coffee cup contaminated with rhinovirus. The study also demonstrated that rhinovirus self-inoculation can result from rubbing the nasal mucosa with contaminated fingers and could lead to infection (29).

LABORATORY EVIDENCE OF ENTERIC VIRUS TRANSMISSION VIA FOMITES

Enteric viruses which cause gastrointestinal symptoms include rotavirus, adenovirus (serotypes 40 and 41), astrovirus, calicivirus (norovirus and sapoviruses), and HAV (40, 41). However, gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea and vomiting are found at a lower frequency in hepatitis A virus infections (74). Enteric viruses spread by the fecal-oral route. In many disease outbreaks viral transmission occurs via contaminated surfaces (1, 2). It has been estimated that one single vomiting incident may produce an estimated 30 million viral particles (7, 39, 61). In addition, at the peak of an enteric virus infection, more than 1011 virions per gram may be excreted in the stool (2, 6, 7, 59, 61, 77). Contamination of fomites from enteric viruses can originate from aerosolized vomit or the transfer of vomit and fecal matter from hands to surfaces (7, 59, 61). Viruses aerosolized from flushing the toilet can remain airborne long enough to contaminate surfaces throughout the bathroom (27). Enteric viruses have been detected in carpets, curtains, and lockers, which can serve as viral reservoirs (39). Surfaces contaminated (e.g., knives or sinks) by virus-infected individuals during food preparation have been documented to be the source of several food-borne outbreaks (53).

Studies on virus survival have indicated that enteric viruses are viable for at least 45 days on nonporous fomites (Table 3). A study by Fischer et al. found that rotavirus stored in feces remained infective for 2.5 months at 30°C and 32 months at 10°C (25). In addition, norovirus, adenovirus, and rotavirus have all been isolated from naturally contaminated fomites. Norovirus has been detected on fomites in hotels, hospital wards, and cruise ships during outbreaks of gastroenteritis (7, 61). GII norovirus and HAV RNA were detected on nonporous surfaces for over 21 days using real-time PCR (J. H. Park, D. H. D. Souza, P. Lui, C. L. Moe, and L. A. Jaykus, unpublished data). Adenovirus has been isolated on drinking glasses from bars and coffee shops, and rotavirus was detected on 16 to 30% of fomites in day care centers (7, 15, 24). Very small amounts of enteric virus (e.g., norovirus, estimated at 10 to 100 virions) can cause infection, with many viral infections being largely asymptomatic or subclinical in healthy adults (7, 59, 61). As a result, viral shedding onto surfaces or the spreading of virions into the environment by infected individuals can go on undetected (6-8, 39).

The spread of HAV, rotavirus, and astrovirus from hands to fomites and vice versa has been well documented in several studies (Table 1). Artificially contaminated finger pads transferred 9.2% of HAV to lettuce (11). Gloved hands transferred feline calicivirus to spatulas, lettuce, forks, doorknobs, and cutting boards (54). A study by Barker et al. demonstrated that norovirus could be transferred from contaminated surfaces to clean hands and then contaminated hands could transfer virus to a secondary surface, such as a phone or door handle (8). It was also found that norovirus-contaminated hands could cross-contaminate a series of seven clean surfaces without additional recontamination of hands (8). Viruses can be easily spread to the mouth when fomites and hands become contaminated (58, 60). A small child puts fingers in his mouth once every 3 minutes, and children up to 6 years average a hand-to-mouth frequency of 9.5 contacts per hour (31, 75).

Like respiratory viruses, laboratory studies documenting direct evidence of enteric virus transmission via surfaces are limited. The Ward study (77) found that all the volunteers who licked a rotavirus-contaminated dinner plate became infected. In the same study, only half of the volunteers who touched the contaminated dinner plate and subsequently licked contaminated fingers became infected (77). Overall, laboratory evidence supporting viral transmission via fomites is considered indirect and circumstantial, but it represents an important component in understanding potential virus transmission (6, 7).

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF VIRUS TRANSMISSION VIA FOMITES

The involvement of fomites in viral disease transmission was first recognized long before the identification of pathogenic organisms, when smallpox outbreaks were traced to imported cotton in 1908 (24). Initially, epidemiology studies on viral disease transmission lacked the scientific methods to detect and distinguish between a variety of bacterial and viral illnesses. Consequently, most epidemiology studies did not identify the microbial cause of a disease, and outbreaks were characterized by disease symptoms only. For example, in 1929 an epidemic of nonbacterial gastroenteritis was described as the winter vomiting disease by epidemiologists (41). Molecular methods are now being used by epidemiologists to link enteric and respiratory viruses to disease outbreaks by identifying the viral pathogens in the host and the environment.

Several epidemiological studies have supported laboratory studies by indicating environmental contamination as a potential vehicle for virus transmission. During an outbreak in a Honolulu nursing home, it was determined that staff hands or fomites (e.g., towels, medical cart items, etc.) spread influenza virus (51). An outbreak of coronavirus (SARS) in a Hong Kong apartment complex may have resulted from fecal-oral transmission combined with environmental contamination (62). Studies in day care centers have detected rotavirus on various surfaces, including toys, phones, toilet handles, sinks, and water fountains (40). The transmission of HAV by contaminated drinking glasses was associated with an outbreak of hepatitis in a public house when an ill barman with HAV served drinks (72). Nursing volunteers who touched infected infants or surrounding fomites developed RSV infection, while nurses with no infant or fomite contact did not develop RSV symptoms (27, 34).

Epidemiological studies also provide additional information by using statistical tools, such as risk assessments and attack rates, to illuminate viral transmission routes. The potential for norovirus transmission via fomites was demonstrated during a wedding reception where the guests suffered a 50% attack rate of gastroenteritis after a kitchen assistant vomited in the sink which was subsequently used for salad preparation (7). When natural rhinovirus colds were studied, rhinovirus was found on 39% of symptomatic individuals' hands (35). Additionally, volunteers touching contaminated objects and/or the fingers of symptomatic individuals had a higher attack rate of colds if they inoculated their own eyes or nose (35). Risk exposure analysis completed after an outbreak of gastroenteritis on a hospital elderly care ward showed that areas where patients vomited were the most significant factor in the spread of norovirus (7). Another hospital ward study demonstrated that rotavirus-contaminated surfaces increased simultaneously as the number of children ill increased (70).

DISINFECTION AND HYGIENE INTERVENTION STUDIES

Like epidemiological studies, many disinfection and hygiene intervention studies lack microbial specificity and identify diseases by symptoms (gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cold symptoms). For example, research by Krilov et al. demonstrated that when environmental surfaces (school bus, toys, etc.) were regularly cleaned or disinfected there was a reduction in gastrointestinal and respiratory illness among children attending the day care center (7). A study in 1980 by Carter et al. found that families using an iodine-based hand wash had lower rates of respiratory disease (16). In addition, a review article by Barker et al. cited over 15 research studies that indicated a decrease in viral contamination and viral infection when hand washing was used regularly as an intervention (7). Subsequently, disinfection and hygiene intervention studies, which have cited a reduction in nonspecific illnesses, only support interruption of disease transmission.

Recently, molecular methods and immunoassays have been used to detect and identify viral presence in the environment before and after disinfection or cleaning. In 2002 norovirus caused consecutive outbreaks of gastroenteritis on various cruise ships (38). Three out of five of the cruise ships required discontinuation of service and aggressive environmental disinfection to halt further infection (38). In a study by Barker et al., surfaces cleaned with a detergent solution spread norovirus to uncontaminated surfaces (8). As a result, the contaminated surface, the cleaning cloth, and the cross-contaminated surface all tested positive for norovirus (8). However, cleaning with a 5,000 ppm chlorine solution was effective in preventing cross-contamination and eliminating norovirus from environmental surfaces (8). In Taiwan a hospital reported that following an outbreak environmental samples which tested positive for coronavirus were negative after resampling the cleaned emergency department and isolating the infected patients (38). A study by Ward et al. demonstrated that spraying rotavirus-contaminated surfaces with disinfectant prevented infection (77). Infection occurred in 63% to 100% of volunteers who touched rotavirus-contaminated surfaces and then licked fingers, and no volunteers became infected after licking contaminated surfaces that had been disinfected (77). Overall, when a disinfection intervention study specifies the microbial cause of disease and details on environmental decontamination, the study relays more practical information about interruption of the specific virus spread.

DISCUSSION

In 2006 the World Health Organization reported that diarrhea and respiratory infections were two of four major diseases influenced by environmental conditions (56). To limit or prevent the spread of viral infections, pathogen transmission needs to be fully understood (27). Both respiratory and enteric viruses have more than one route of transmission (30). Respiratory viruses are known to be spread by person-to-person contact, the airborne route, and contaminated surfaces or fomites (7, 27). Enteric viruses are spread by the fecal-oral route via environmental and person-to-person contact (7, 61, 77). Respiratory viruses appear to be more efficient in disease spread (via the airborne route) than enteric viruses. Respiratory viruses spread faster (from a sneeze, airborne virus travels 3 m at 20 m/s) (78), have short incubation times (1 to 8 days), and greater infectivity (a lower dosage causes infection) (39). On the other hand, enteric viruses spread more slowly (water or food), have longer incubation times (1 to 60 days), and require a higher viral dosage (lower infectivity) (59). These facts suggest that enteric and respiratory viral disease transmissions have nothing in common. However, person-to-person contact and environmental contamination are common routes of transmission for both types of virus. Virus spread by person-to-person contact can be interrupted with isolation of the viral carrier. Yet, isolation may prove to be impractical or difficult if there are many people or if the source of infection is unknown (69). Consequently, interrupting disease spread via indoor fomites is one of the more practical methods for limiting or preventing enteric and respiratory viral infections.

A majority of respiratory viruses are enveloped (parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, RSV, and coronavirus) and survive on surfaces from hours to days. In contrast, most enteric viruses are nonenveloped and survive on fomites from weeks to months. Studies have demonstrated that viral transfer from hands to surrounding surfaces is possible in 7 out of 10 viruses reviewed (Table 4). Epidemiological studies have verified naturally occurring outbreaks for 8 out of 10 viruses (HAV, RSV, norovirus, rotavirus, influenza virus, coronavirus, astroviruses, and adenoviruses). Investigations of disease outbreaks and disinfection intervention studies have documented indoor surfaces as reservoirs for pathogenic viruses with potential spread of infectious disease (19). Epidemiological studies have also identified fomites as a potential vehicle for disease transmission. Hygiene and disinfection intervention studies have demonstrated two concepts that support transmission of viral infection via fomites. First, proper cleaning of hands decreases respiratory and gastrointestinal illness. Second, disinfection of fomites can decrease surface contamination and may interrupt disease spread (norovirus, coronavirus, and rotavirus). In addition, laboratory evidence from studies by Ward et al. (rotaviruses) (77) and Hendley et al. (rhinoviruses) (34) support viral transmission via fomites. Disease transmission via contaminated fomites has been proven or is suspected for all 10 enteric and respiratory viruses reviewed (Table 3). Generally, research evidence suggests that a large portion of enteric and respiratory illnesses can be prevented through improved environmental hygiene, with an emphasis on better hand and surface cleaning practices (39).

TABLE 4.

General characteristics and roles of fomites in viral transmission

| Virus | Optimal environmental conditions for survival (reference[s]) | Viral transfer via fomite (reference[s]) | Minimally infectious dose of virus (reference[s]) | Evidence of transmission by fomite (reference[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Composition of surface more important than humidity and temp (3, 24) | From porous (tissues, gloves) and nonporous (countertops) fomites (33) | Intranasal inoculation, humans, 100-640 TCID (54, 55) | Proven (3, 22) |

| Rhinovirus | Survived well in high humidity but poorly under dry conditions (64) | Clean hands pick up virus when handling contaminated fomites (5, 52); 70% of virus on hands transferred to recipients' fingers (30) | Intranasal inoculation, humans, 0.032-0.4 TCID50 (55); reported elsewhere as 1-10 TCID50 (7, 28, 39) | Proven, considered minor (3, 22) |

| Influenza virus | Survival at lab temp of 28°C and 40% humidity for 48 h on dry surface; 72 h for avian influenza virus on dry surface (73); 72 h forinfluenza A virus on wet surface (9) | Virus transferred from contaminated surface to hands for up to 24 h after inoculation (9) | Intranasal inoculation, humans, 2-790 TCID50 (54, 55) | Proven, considered secondary or minor (38) |

| Parainfluenza virus | Survival decreases above 37°C; stable at 4°C, pH 7.4 to 8.0, and low humidity; recovered after freezing for 26 yrs (37) | Stainless steel surfaces to clean fingers (5) | Intranasal inoculation, humans, 1.5-80 TCID50 (parainfluenza virus 1) (7, 38, 54) | Not proven, indirect evidence supports (3, 22) |

| Coronavirus | Humidity 55-77% and temp 21°C remained infective up to 6 days in PBS (50); remains infective 1-2 days in feces (68) | Theoretically possible but not studied (68) | Not found | Not proven but suspected (3, 38, 58) |

| Feline calicivirus | Survived at 4°C when dried on coverslip for 56 days; survival decreased with temp (21); sensitive to humidity in 30-70% range (19, 61) | From gloved hands to kitchen utensils and doorknob and vice versa (53); from contaminated surface to clean hands to phone, door handle, or water tap handle (8) | Estimated to be as few as 10-100 particles (7, 8, 17, 39) | Not proven, indirect evidence supports, CDC lists surface contamination (17, 41) |

| Rotavirus | Remained infective for 32 mos at 10°C and 2&12frac; mos at 30°C when stored in feces (25) | 16% viral transfer from contaminated fingertips to steel disc after 20 min (4) | Not found; estimated at 10-100 TCID50 (7, 55) | Proven (7, 22) |

| Hepatitis A virus | Survival inversely proportional to relative humidity and temp, 5°C is optimal temp (1, 48) | 25% viral transfer from fingers to disc; moisture facilitated transfer (47); 9.2% of virus transferred to lettuce (11) | Estimated at 10-100 TCID50 (55, 59) | Accepted (food and fecally contaminated surfaces) (1, 41) |

| Adenovirus | Survived shorter periods in presence of feces and at lower humidity (1, 42, 46, 61) | Not found | Intranasal, 150 TCID50; oral, 1,000 TCID50 (capsule form of serotypes 4 and 7) (54) | Widely accepted, contaminated surfaces (1) |

| Astrovirus | Survived 4°C on china for 60 days and paper for 90 days; faster decay at higher temp (2, 61) | Not found | Not found | May play an important role in secondary transmission (2, 61) |

Additional studies investigating the infectious dose of enteric and respiratory viruses would improve and/or validate current water, air, and other environmental exposure guidelines. There is also a need for better quantitative data in the form of viral inactivation rates and transfer rates on/from fomites. Viral research that further investigates survival on fomites and hand-to-surface transfer would be useful in understanding the ecology of fomites in virus transmission. Studies targeting the distribution of viruses on fomites within the home, work, and public places could aid the targeting of cleaning and disinfection procedures. Generally, new data could be used in risk assessment models that associate viral infection with fomite contact or to improve viral transmission models. The potential success of risk assessment interventions would benefit both public health and the medical community.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Center for Advancing Microbial Risk Assessment funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security University Programs grant number R3236201.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abad, F. X., R. M. Pinto, and A. Bosch. 1994. Survival of enteric viruses on environmental fomites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3704-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abad, F. X., C. Villena, S. Guix, S. Caballero, R. M. Pinto, and A. Bosch. 2001. Potential role of fomites in vehicular transmission of human astroviruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3904-3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aitken, C., and D. J. Jeffries. 2001. Nosocomial spread of viral disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:528-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansari, S. A., S. A. Sattar, V. S. Springthorpe, G. A. Wells, and W. Tostowaryk. 1988. Rotavirus survival on hands and transfer of infectious virus to animate and nonporous inanimate surfaces. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1513-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari, S. A., V. S. Springthorpe, S. A. Sattar, S. Rivard, and M. Rahman. 1991. Potential role of hands in the spread of respiratory viral infections-studies with human parainfluenza 3 and rhinovirus 14. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2115-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker, J. 2001. The role of viruses in gastrointestinal disease in the home. J. Infect. 43:42-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker, J., D. Stevens, and S. F. Bloomfield. 2001. Spread and prevention of some common viral infections in community facilities and domestic homes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker, J. D., I. B. Vipond, and S. F. Bloomfield. 2004. Effects of cleaning and disinfection in reducing the spread of norovirus contamination via environmental surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 58:42-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bean, B., B. M. Moore, B. Sterner, L. R. Peterson, D. N. Gerding, and H. H. Balfour. 1982. Survival of influenza viruses on environmental surfaces. J. Infect. Dis. 146:47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellamy, K., K. L. Laban, K. E. Barrett, and D. C. S. Talbot. 1998. Detection of viruses and body fluids which may contain viruses in the domestic environment. Epidemiol. Infect. 121:673-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bidawid, S., J. M. Farber, and S. A. Sattar. 2000. Contamination of food handlers: experiments on hepatitis A virus transfer to food and its interruption. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2759-2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone, S. A., and C. P. Gerba. 2005. The occurrence of influenza A virus on household and day care center fomites. J. Infect. 51:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brady, M. T., J. Evans, and J. Cuartas. 1990. Survival and disinfection of parainfluenza viruses on environmental surfaces. Am. J. Infect. Control 18:18-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butcher, W., and D. Ulaeto. 2005. Contact inactivation of orthopoxviruses by household disinfectants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butz, A. M., P. Fosarelli, J. Dick, T. Cusack, and R. Yolken. 1993. Prevalence of rotavirus on high-risk fomites in day-care facilities. Pediatrics 92:202-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter, C. H., J. O. Hendley, L. A. Mika, and J. M. Gwaltney. 1980. Rhinovirus inactivation by aqueous iodine in vitro and on skin. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 165:380-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control. 2002. Norovirus activity—United States 2002. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:41-44. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5203a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couch, R. B. 1995. Orthomyxoviruses, p 1-22. In S. Baron (ed.), Medical microbiology. University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Tex. http://www.gsbs.utmb.edu/microbook/ch058.htm. [PubMed]

- 19.Cozad, A., and R. D. Jones. 2003. Disinfection and the prevention of infectious disease. Am. J. Infect. Control 31:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jong, J. C., G. F. Rimmelzwaan, R. A. M. Fouchier, and A. D. M. E. Osterhaus. 2000. Influenza virus: a master of metamorphosis. J. Infect. 40:218-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donaldson, A. I., and N. P. Ferris. 1976. The survival of some airborne animal viruses in relation to relative humidity. Vet. Microbiol. 1:413-420. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doultree. J. C., J. D. Druce, C. J. Birch, D. S. Bowden, and J. A. Marshall. 1999. In activation of feline calicivirus, a Norwalk virus surrogate. J Hosp. Infect. 41:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowell, S. F., J. M. Simmerman, D. D. Erdman, J. W. Juinn-Shyan, A. Chaovavanich, M. Javadi, J. Y. Yang, L. J. Anderson, S. Tong, and M. S. Ho. 2004. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus on hospital surfaces. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:652-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.England, B. L. 1982. Detection of viruses on fomites, p. 179-220. In C. P. Gerba and S. M. Goyal (ed.), Methods in environmental virology. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 25.Fischer, T. K., H. Steinsland, and P. Valentiner-Branth. 2002. Rotavirus particles can survive storage in ambient tropical temperatures for more than 2 months. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4763-4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerba, C. P., C. Wallis, and J. L. Melnick. 1975. Microbiological hazards of households toilets: droplets production and the fate of residual organisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 30:229-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldmann, D. A. 2000. Transmission of viral respiratory infections in the home. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19(Suppl. 10):S97-S102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwaltney, J. M. 2002. Clinical significance and pathogenesis of viral respiratory infections. Am. J. Med. 112:S13-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwaltney, J. M., and J. O. Hendley. 1982. Transmission of experimental rhinovirus infection by contaminated surfaces. Am. J. Epidemiol. 116:828-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwaltney, J. M., P. B. Moskalski, and J. O. Hendley. 1978. Hand to hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann. Intern. Med. 88:463-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas, C. N., J. B. Rose, and C. P. Gerba. 1999. Microbial agents and their transmission, p. 35-50. In C. N. Haas, J. B. Rose, and C. P. Gerba (ed.), Quantitative microbial risk assessment. J. Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 32.Hall, C. B., and R. G. Douglas. 1981. Modes of transmission of respiratory syncytial virus. J. Pediatr. 99:100-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall, C. B., R. G. Douglas, Jr., and J. M. Geiman. 1980. Possible transmission by fomites of respiratory syncytial virus. J. Infect. Dis. 141:98-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall, C. B., R. G. Douglas, Jr., K. C. Schnabel, and J. M. Geiman. 1981. Infectivity of respiratory syncytial virus by various routes of inoculation. Infect. Immunol. 33:779-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendley, J. O., and J. M. Gwaltney. 1988. Mechanisms of transmission of rhinovirus infection. Epidemiol. Rev. 10:242-258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendley, J. O., R. P. Wenzel, and J. M. Gwaltney. 1973. Transmission of rhinovirus colds by self-inoculation. N. Engl. J. Med. 288:1361-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendrickson, K. J. 2003. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:242-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hota, B. 2004. Contamination, disinfection and cross-colonization: are hospital surface reservoirs for nosocomial infection? Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1182-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. 2002. The infection potential in the domestic setting and the role of hygiene practice in reducing infection. http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/2003/2library/2lbr00.asp#IFHCONSENSUSPUBLICATIONS.

- 40.Keswick, B. H., L. K. Pickering, H. L. DuPont, and W. E. Woodward. 1983. Survival and detection of rotaviruses on environmental surfaces in day care centers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46:813-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koopmans, M., C. H. von Bonsdorff, J. Vinje, D. de Medici, and S. Monroe. 2002. Foodborne viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:187-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koopmans, M., and E. Duizer. 2004. Foodborne viruses: an emerging problem. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 90:23-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laurance, J. 2003. What is this disease and why is it so deadly. Ecology. http://www.ecology.com/ecology-news-links/2003/articles4-2003/4-25-03/sars.htm.

- 44.Leclair, J. M., J. Fredman, B. F. Sulivan, C. M. Crowley, and D. A. Goldmann. 1987. Prevention of nosocomial respiratory virus infections through compliance with glove and gown isolation precautions. N. Engl. J. Med. 317:329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lew, J. F., C. L. Moe, S. S. Monroe, J. R. Allen, B. M. Harrison, B. D. Forrester, S. E. Stine, P. A. Woods, J. C. Hierholzer, and J. E. Herrmann. 1991. Astrovirus and adenovirus associated with diarrhea in children in day care settings. J. Infect. Dis. 164:673-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahl, M. C., and C. Sadler. 1975. Virus survival on inanimate surfaces. Can. J. Microbiol. 21:819-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mbithi, J. N., V. S. Springthorpe, J. R. Boulet, and S. A. Sattar. 1992. Survival of hepatitis A virus on human hands and its transfer on contact with animate and inanimate surfaces. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:757-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mbithi, J. N., V. S. Springthorpe, and S. A. Sattar. 1991. Effect of relative humidity and air temperature on survival on survival of hepatitis A virus on environmental surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1394-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McElhaney, J. 2003. Epidemiology in elderly people. Influenza Info. News 16:3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monto, A. S. 2002. Epidemiology of viral respiratory infections. Am. J. Med. 112(Suppl. 1):4-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morens, D. M., and V. M. Rash. 1995. Lessons from a nursing home outbreak of influenza A. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 16:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pancic, F., D. C. Carpenter, and P. E. Came. 1980. Role of infectious secretions in the transmission of rhinovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 12:567-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulson, D. S. 2005. The transmission of surrogate Norwalk virus—from inanimate surfaces to gloved hands: is it a threat? Food Prot. Trends 25:450-454. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plotkin, S. A., and M. Katz. 1967. Minimal infective doses of viruses for man by the oral route, p. 151-156. In G. Berg (ed.), Transmission of viruses by the water route. J. Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 56.Pruss-Ustun, A., and C. Covalan. 2006. Almost a quarter of all disease caused by environmental exposure. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr32/en/.

- 55.Public Health Agency of Canada. 2001. Material safety data sheet: infectious substances. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/msds-ftss/.

- 57.Reiling, J. 2000. Dissemination of bacteria from the mouth during speaking, coughing and otherwise. JAMA 284:156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reynolds, K. A., P. Watts, S. A. Boone, and C. P. Gerba. 2005. Occurrence of bacteria and biochemical biomarkers on public surfaces. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 15:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rusin, P., C. Enriquez, D. Johnson, and C. P. Gerba. 2000. Environmentally transmitted pathogens, p. 448, 473-484. In R. M. Maier, I. L. Pepper, and C. P. Gerba (ed.), Environmental microbiology. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 60.Rusin, P., S. Maxwell, and C. P. Gerba. 2002. Comparative surface to hand and finger to mouth transfer efficiency of gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria and phage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:585-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rzezutka, A., and N. Cook. 2004. Survival of human enteric viruses in the environment and food. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:441-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sampathkumar, P., Z. Temesgen, T. F. Smith, and R. L. Thompson. 2003. SARS: epidemiology, clinical presentation, management, and infection control measures. Mayo Clinic Proc. 78:882-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sattar, S. A., M. Abebe, A. Bueti, H. Jampani, and J. Newman. 2000. Determination of the activity of an alcohol-based hand gel against human adeno-, rhino-, and rotaviruses using the fingerpad method. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 21:516-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sattar, S. A., Y. G. Karim, V. S. Springthorpe, and C. M. Johnson-Lussenburg. 1987. Survival of human rhinovirus type 14 dried onto nonporous inanimate surfaces: effect of relative humidity and suspending medium. Can. J Microbiol. 33:802-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sattar, S. A., N. Lloyd-Evans, V. S. Springthorpe, and R. C. Nair. 1986. Institutional outbreaks of rotavirus diarrhea: potential role of fomites and environmental surfaces as vehicles for virus transmission. J. Hyg. (London) 96:277-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sattar, S. A. 2001. Survival of microorganisms on animate and inanimate surfaces and their disinfection, p. 195-205. In W. A. Rutala (ed.), Disinfection, sterilization and antisepsis: principles and practices in healthcare facilities. Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc., Washington, D.C.

- 67.Schwartz, T., S. Hoffmann, and U. Obst. 2003. Formation of natural biofilms during chlorine dioxide and UV disinfection in public drinking water distribution systems. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sizun, J., M. W. Yu, and P. J. Talbot. 2000. Survival of human coronavirus 229E and OC43 in suspension and after drying on surfaces: a possible source of hospital-acquired infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 46:55-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sobsey, M. D., and J. S. Meschke. 2003. Virus survival in the environment with special attention to survival in sewage droplets and other environmental media of fecal or respiratory origin. http://www.iapmo.org/common/pdf/ISS-Rome/Sobsey_Environ_Report.pdf.

- 70.Soule, H., O. Genoulaz, B. Gratacap-Cavalier, M. R. Mallaret, P. Morand, P. Francois, D. Luu Duc Bin, A. Charvier, C. Bost-Bru, and J. M. Seigneurin. 1999. Monitoring rotavirus environmental contamination in a paediatric unit using polymerase chain reaction. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:432-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Springthorpe, V. S., and S. A. Sattar. 1990. Chemical disinfection of virus-contaminated surfaces. Crit. Rev. Environ. Control 20:169-229. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sundkvist, T., G. R. Hamilton, B. M. Hourihan, and I. J. Hart. 2000. Outbreak of hepatitis A spread by contaminated drinking glasses in a public house. Commun. Dis. Public Health 3:60-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tiwari, A., D. P. Patnayak, Y. Chandler, M. Parsad, and S. M. Goyal. 2006. Survival of two avian respiratory viruses on porous and nonporous surfaces. Avian Dis. 50:284-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tong, M. J., N. S. El-Farra, and M. I. Grew. 1995. Clinical manifestations of hepatitis A: recent experience in a community teaching hospital. J. Infect. Dis. 171(Suppl. 1):S15-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tulve, N. S., J. C. Suggs, T. McCurdy, A. Elaine, C. Hubal, and J. Moya. 2002. Frequency of mouthing behavior in young children. J. Exp. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 12:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.U.S. Department of Commerce National Climatic Data Center. 2002. Average relative humidity. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/avgrh.html.

- 77.Ward, R. L., D. I. Bernstein, D. R. Knowlton, J. R. Sherwood, E. C. Young, T. M. Cusack, J. R. Rubino, and G. M. Schiff. 1991. Prevention of surface-to-human transmission of rotavirus by treatment with disinfectant spray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1991-1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao, B., Z. Zhao, and L. Xianing. 2005. Numerical study of the transport of droplets or particles generated by respiratory systems indoors. Build. Environ. 40:1032-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]