Summary

Protein modification by ubiquitin is a central regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells. Recent proteomics developments in mass spectrometry enable systematic analysis of cellular components in the ubiquitin pathway. Here, we review the advances in analyzing ubiquitinated substrates, determining modified lysine residues, quantifying polyubiquitin chain topologies, as well as profiling deubiquitinating enzymes based on the activity. Moreover, proteomic approaches have been developed for probing the interactome of proteasome and for identifying proteins with ubiquitin-binding domains. Similar strategies have been applied on the studies of the modification by ubiquitin-like proteins as well. These strategies are discussed with respect to their advantages, limitations and potential improvements. While the utilization of current methodologies has rapidly expanded the scope of protein modification by the ubiquitin family, a more active role is anticipated in the functional studies with the emerging of quantitative mass spectrometry.

1. Introduction

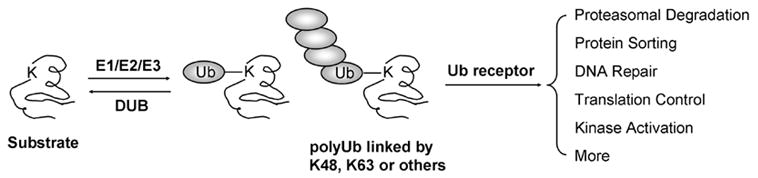

Ubiquitin modification of cellular substrates is a highly conserved pathway involved in almost all cellular events, such as proteasome-mediated degradation [1–3], protein sorting [4], DNA repair [5], and inflammation [6]. Ubiquitin is covalently attached to its protein targets by a cascade of enzymatic reactions through Ub-activating enzyme (E1), Ub-conjugating enzyme (E2), and Ub ligase (E3). As a result, the carboxyl group of the glycine residue at Ub’s C-terminus forms an isopeptide bond with the epsilon amino group of a lysine residue in substrates (Fig. 1). Alternatively, the N-terminal amino group [7] or even cysteine residues [8] can serve as ubiquitination sites in some proteins. In addition to monoubiquitination, many substrates are modified by polyubiquitin (polyUb) chains, in which additional Ub molecules are conjugated to all seven lysine residues of preexisting Ub to form polymers [9], providing an opportunity for enhancing structural diversity by the formation of various topologies. Opposite to the conjugation, Ub is removed from the substrates or free polyUb chains by a large number of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [10–12]. Recently, a computational analysis has revealed that the numbers of E1, E2, E3 and DUB in human proteome are estimated to be 16, 53, 527, and 184, respectively [13], suggesting that the scope of protein ubiquitination is substantially large. Among so many enzymes and substrates, how is the specificity achieved during multiple stages of enzymatic reactions and signal transduction in the pathways? It is generally believed that the specificity is largely determined by the recognition of substrates by Ub enzymes (mainly E3 ligases) and the interaction between ubiquitin moieties (monoUb or polyUb) with Ub receptors [14, 15] (Fig. 1). Numerous ubiquitin receptor proteins (>250 in human) have been identified to display Ub-binding domains (UBD) [15–17]. To date, at least 11 families of UBDs have been identified in many different sequence contexts. In addition to ubiquitin, numerous ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls) have regulatory function in many cellular processes by modifying proteins and even lipids [18].

Fig. 1.

The key steps in the ubiquitin pathway including protein conjugation, recognition and function.

Recent development in mass spectrometry (MS) enables identification and even quantification of hundreds to thousands of proteins with femtomolar or even sub-femtomolar sensitivity [19–21]. Two common proteomics platforms are GeLC-MS/MS and LC/LC-MS/MS. In GeLC-MS/MS, a protein mix is separated on a SDS gel and then subjected to in-gel digestion. The resulting peptides are resolved on a reverse-phase liquid chromatography and detected by coupled tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Alternatively, LC/LC-MS/MS permits the analysis of a digested peptide mixture in two sequential steps of chromatography followed by tandem mass spectrometry. Both technologies have been applied to identify proteins involved in the Ub and Ubls pathways, such as proteome modified by ubiquitin or Ubls, proteasome interactome, and Ub-binding proteins [22, 23]. Moreover, several strategies have been developed to determine the ubiquitination sites on the substrates, as well as profile ubiquitinated proteome and other constituents in the pathway.

2. Analysis of ubiquitinated proteome

As the abundance of ubiquitinated proteins is often low in cells and mass spectrometry is biased toward abundant proteins, it is essential to pre-enrich ubiquitinated proteins prior to the analysis. Many affinity approaches have been tested to isolate Ub-conjugates under native and denaturing conditions, including ubiquitin antibodies, ubiquitin-binding proteins, and epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g. FLAG, HA-tag, myc-tag, His-tag, and biotin). To date, the most successful method is to purify ubiquitinated substrates using His-tag under denaturing conditions, in which non-specific protein binding is reduced to very low level due to minimal protein-protein interaction.

Several proteomic studies of ubiquitinated proteins are summarized with regard to starting material, purification strategies, selection of MS methods, and the total number of Ub-conjugate candidates identified (Table 1). In the case of yeast, Peng et al. reported a large-scale analysis of Ub-conjugates from a yeast strain expressing only His-tagged ubiquitin [9, 24]. Ub-conjugates were isolated, digested in solution, and analyzed by two dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS). A negative control was performed using an isogenic yeast strain expressing wild type ubiquitin. A total of 1,075 proteins were identified in the enriched sample, after discarding 48 proteins present in the negative control. While some of background proteins are endogenous His-rich proteins, the remaining contaminants are protein components of extremely high abundance in cells. To further reduce the non-specific binding, a tandem tag consisted of six His residues and a biotin motif was generated to purify yeast ubiquitinated proteins in two steps under denaturing condition, resulting in the identification of 258 proteins [25]. The method of his tagging has been extended to mammalian cells with some success [26] but more efforts are needed to improve the purity of ubiquitinated species because, at least partially, there are more native His-rich proteins in mammalian proteome. In addition, the expression level of His-tagged ubiquitin is often lower than that of endogenous Ub expressed from multiple Ub genes in mammal. As the strategy of tagged ubiquitin cannot be applied to samples without genetic manipulation, several groups carried out affinity purification of native Ub-conjugates using ubiquitin antibodies [27, 28]. Matsumoto et al. examined both native and denaturing conditions for the antibody affinity capture, and identified 670 and 345 proteins, respectively, indicating that ~50% of proteins enriched under native conditions are associated with the columns despite that they may not be modified by ubiquitin directly. In addition, in vitro ubiquitination assay was also used for synthesizing His-tagged Ub-conjugates for proteomic analysis [29], which may be useful to identify specific substrates of a ligase in a defined reconstituted system. Indeed, a similar analysis was used to identify many substrates of the BRCA1-BARD1 Ub ligase [30]. Alternatively, a high throughput screen was developed to screen for substrates of specific ligases using recombinant proteins in reconstituted ubiquitination reactions [31].

Table 1.

Comparison of multiple analyses of ubiquitinated proteins by mass spectrometry

| Yeast | ||||

|

| ||||

| Peng et al. [9] | Hitchcock et al. [31] | Mayor et al. [63] | Tagwerker et al. [25] | |

| Ub tags | (His)6-Ub | (His)6-Ub | (His)8-Ub | (His)6-biotin-Ub |

| Purification strategies | Denaturing nickel chromatography | Membrane isolation & denaturing nickel column | Ub binding domain (Rpn10) affinity column (native condition), denaturing Ni++ column | denaturing nickel column & biotin affinity column |

| MS methods | LC/LC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS |

| #Protein identified | 1,075 | 211 | 127 | 258 |

| #Proteins with identified Ub sites | 72 (110 sites) | 29 (34 sites) | 1 (4 sites) | 15 (21 sites) |

| Mammalian cells | ||||

|

| ||||

| Kirkpatrick et al. [26] | Matsumoto et al. [27] | Vasilescu et al. [28] | Gururaja et al. [29] | |

| Ub tags | (His)6-Ub | No tag | No tag | (His)6-Ub |

| Purification strategies | Native nickel column | Ab affinity column (native & denaturing) | Native Ab affinity column | Denaturing nickel chromatography |

| MS methods | LC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | GeLC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS |

| #Protein identified | 22 | 670/345* | 70 | 80 |

| #Proteins with identified Ub sites | 1 (4 sites) | 11 (18 sites) | not available | not available |

the numbers of proteins identified under native and denaturing conditions, respectively

Although the proteins co-purified with Ub-conjugates can be controlled at low level using highly stringent conditions, it is still possible that many co-purified proteins are present in the enriched samples and can be detected by highly sensitive mass spectrometry. Therefore it is important to validate if the identified proteins are indeed modified by ubiquitin. Whereas negative controls have been implemented in all above experiments to differentiate contaminants from Ub-conjugates, the quality of sample preparation is dependent on the method selected and even on the experimental setting in labs. Moreover, Ub-conjugates can be verified by the determination of ubiquitination sites, gel mobility shift caused by addition of molecular weight, and independent immunoprecipitation analysis [24].

The success of large-scale analysis of Ub-conjugates opens the door for profiling ubiquitinated proteome under different conditions or from cells expressing different mutations relevant to specific ubiquitination pathways. Based on this strategy, Hitchcock et al. have identified a subset of membrane-associated ubiquitin substrates in the endoplasmic reticulum degradation pathway (ERAD). For these experiments, they created yeast strains containing tagged ubiquitin with and without mutations in both the ER resident ubiquitinating enzyme UBC7 and the ERAD associated protein NPL4. Comparing the relative levels of ubiquitination on proteins derived from yeast strains without and without the ERAD-associated mutations revealed 83 potential substrates in the ERAD ubiquitination pathway [32].

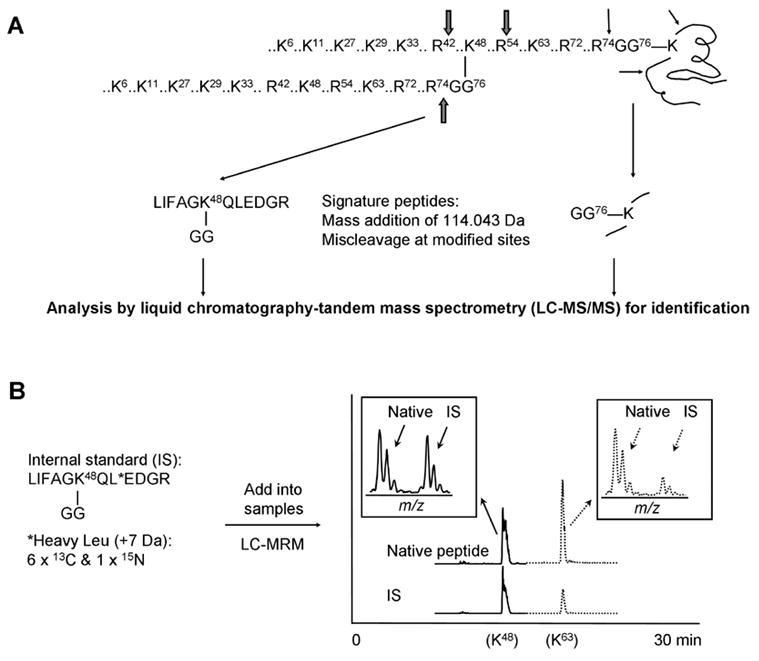

3. Identification of ubiquitinated sites by mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is capable of mapping ubiquitination sites on modified amino acids [9, 19, 33]. After trypsin digestion the original ubiquitin molecule is trimmed to a di-peptide (-GG) remnant that adds a monoisotopic mass of 114.043 Da on the affected lysine residue (Fig. 2A), and sometimes miscleavage in ubiquitin generates a longer tag (-LRGG) [34]. This modification leads to unique MS/MS spectra that can be matched by database-searching algorithms. Furthermore, the modified peptides carry a missed proteolytic cleavage because trypsin digestion cannot occur at the modified lysine sites. The analysis of ubiquitinated sites can be facilitated by using high resolution mass spectrometry [35] and N-terminal sufonation for specific signature ions [36]. Although N-terminal ubiquitination has been documented for some substrates [7], this mode of conjugates has not been detected in the global analysis in yeast (Peng J., unpublished data). In addition, the same strategy can be used to map modification sites by ubiquitin-like proteins. It should be noted that trypsin digestion of some Ubls (e.g. Nedd8 and ISG15) produces the same -GG tag as ubiquitin, so it is a prerequisite to separate them before mass spectrometric analysis.

Fig. 2.

(A) The strategy for identifying Ub modification sites in protein targets and for analyzing polyUb chain topologies. All tryptic sites in ubiquitin are shown. (B) Measurement of the abundance of Ub linkages by the AQUA strategy using mass spectrometry. The synthesis of stable isotope labeled internal standard as exemplified by K48 linkage. It is also shown to use liquid chromatography coupled with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) to quantify K48 and K63 linkages.

The strategy has been applied to a number of large-scale analysis (Table 1) and individual targets. The identification of ubiquitination sites permit targeted mutagenesis to investigate the specificity of ubiquitination sites and the function of protein ubiquitination. In some cases, site-directed mutagenesis of identified ubiquitinated sites has significantly reduced the modification of the proteins and prevented the proteins from degradation [33, 37, 38]. A bioinformatics analysis of identified hundreds of sites has also revealed some sequence preference of ubiquitination sites [39]. On the other hand, ubiquitin can be attached to many lysine residues in a structural region of substrates, and mutation of some sites may have little effect on ubiquitination until all lysine residues are substituted [40]. It is possible that the specificity of ubiquitination sites is dependent on the substrates and their corresponding ubiquitin enzymes.

4. Identification and quantification of polyUb chain topologies

The method for analyzing ubiquitinated sites also enables direct determination of lysine residues involved in polyUb assembly (Fig. 2A), and global analysis of Ub-conjugates has revealed surprising complexity of polyUb chains. In S. cerevisiae [9], all seven lysine residues have been found to participate in the formation of Ub-Ub linkages, with a relative abundance order of K48 > K11 and K63 >> K6, K27, K29 and K33 based on semi-quantitative estimation from spectral counts. Interestingly, forked polyUb chains are present in cells because one Ub peptide has both K29 and K33 modified by ubiquitin [9]. More recently, another study has also shown that Ub can modify K11 and K27, or K27 and K29 simultaneously [25]. In mammalian cells, while K27-linked polyUb chains have been suggested by in vitro ubiquitination assay using mutant ubiquitin [41], all other linkages have been detected directly by mass spectrometry [24, 27, 42].

Many lines of evidence support the concept that the outcome of ubiquitination on substrates is largely dependent on the length and topology of attached ubiquitin chains [14, 23]. For instance, a canonical K48 polyUb chain is the principle signal for targeting substrates for degradation by 26S proteasome [43]. Genetic and biochemical evidence supported that K29-linked chain is required for efficient degradation of substrates through the UFD (ubiquitin-fusion degradation) pathway [44, 45]. Interestingly, the polyUb chains assembled on the UFD substrate are heteropolymers, which are initiated at K29 but elongated through K48 [45, 46]. By contrast, polyUb chains linked through K63 and mono-ubiquitination act in a wide range of other processes [4, 6, 42, 47], but the physiological roles of other linkages are poorly characterized. Moreover, the diverse function of polyUb chains (at least K63 and k48 linkages) is also supported by genetic and structural evidence [47–50]. However, it is not known if a number of polyUb chains can be specifically recognized by different Ub receptors. One of the challenges is how to quantitatively define the polyUb chain structure.

PolyUb linkages can be quantified by the Absolute quantification (AQUA) strategy [51], in which all seven ubiquitinated –GG peptides are labeled by stable isotope during chemical synthesis, and then quantified as internal standards [52, 53]. The internal standards behave identically to their native partners during handling, but are distinguishable in a mass spectrometer (Fig. 2B). After spiking in the internal standards, protein samples are digested with trypsin to produce native -GG peptides from polyUb chains. The instrument can be set in a mode of selected reaction monitoring (SRM), also termed multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) to improve detection sensitivity. We have measured the abundance ratio of K6:K11:K27:K29:K33:K48:K63 linkages to be ~40:120:20:15:5:100:40 during the log growth phase in yeast, and the sum of non-K48 linkages is more than twice as abundant as the canonical K48 linkage. Moreover, higher concentration of ubiquitin results in the accumulation of almost all linkages, whereas inhibition of proteasome activity has augmented only K48 and K29-linked chains, emphasizing their roles in proteolysis and suggesting non-proteolytic functions of other linkages in vivo [53]. However, the result on global dynamics of Ub linkages cannot rule out the possibility that individual protein functions differently. Gygi’s group has used the method to analyze the frequency of different linkages on EGF receptor [42] and cylin B1 [52]. EGF receptor has been found to be ubiquitinated with different lengths and linkages including about 49% mono-Ub, 40% K63, 6% K48, 3% K11 and 2% K29 linkages, consistent with the role of ubiquitination in protein trafficking and lysosomal degradation. In vitro ubiquitination of cylin B1 generates mono-Ub and short polyUb chains linked by K48, K11 and K63, which can be degraded by proteasome effectively. More studies are needed to address if this phenomenon also occur in vivo.

5. Activity-based profiling of DUBs by mass spectrometry

The deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are specific proteases that recognize Ub and cleave the isopeptide bond formed by the last glycine residue of ubiquitin. There are at least five families of DUBs: Ub C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Ub-specific proteases (USPs), MJD proteases, OTU proteins, and JAMM motif metalloproteases [12]. The first four families are cysteine proteases, and JAMMs are zinc-dependent metalloproteases. These enzymes are responsible for processing inactive Ub precursors, recycling ubiquitin to maintain free Ub pool and editing Ub-conjugates [10, 11].

Activity-dependent protein capture coupled with mass spectrometry has been used to characterize DUB enzymes and to perform expression profiling of DUBs in various cells and tissues. Borodovsky et al [54] utilized N-terminally HA-tagged Ub probes that contain suicide thiol-reactive groups at the carboxyl termini. DUBs from a mouse cell line were labeled with the probes, affinity-purified, and then identified by tandem mass spectrometry. In addition to the rediscovery of 3 UCHs and 20 UBPs, a novel DUB family was revealed to contain OTU domains, and further validated in activity assays. Similar approach with biotin-tagged Ub aldehyde led to the same finding as well [55]. The method has also been adapted to ubiquitin-like proteins, resulting in the identification of Nedd8-specific protease DEN1/NEDP1/SENP8 DEN1 [56–58]. Based on this chemistry-based proteomics approach, Ovaa et al. [59] compared the profile of active DUBs in normal, Epstein–Barr virus-infected, and malignant human cells, and revealed functional relationships between specific DUBs and virus infection or the induction of mitogen activity. The same approach was applied to analyze the activities of individual DUBs in biopsies of human papillomavirus (HPV) induced cervical carcinoma and adjacent normal tissues [60].

6. Identification of proteasome-associated proteins

To understand the regulation of proteasomal activity, several systematic analyses were carried out to identify proteasome-associated proteins (Table 2) [61–63]. The proteasome is a macromolecular multi-catalytic complex that degrades ubiquitinated substrates, and its structure and activity are influenced by a wide range of associated proteins [14, 64]. So far the most comprehensive analysis of the proteasome complex was performed by Guerrero et al. [61]. The proteasome-associated proteins were cross-linked together by formaldehyde and purified under denaturing condition through an affinity tag composed of hexahistidine and in vivo biotinylation signal. The cross-linking step stabilizes transient protein-protein interactions and thus increases the sensitivity of the method. Quantitative analysis was implemented to differentiate contaminants from specific binding proteins. The analysis identified all of the known proteasome subunits and assigned four additional subunits. A total of 64 proteins were found to be associated with the proteasome, 42 of which were newly identified, including some Ub receptors, ubiquitinated substrates, chaperons, transcription factors and translational factors. The study of these proteins will lead to new perspectives on the dynamics of this unique proteolytic machine.

Table 2.

Comparison of multiple analyses of proteasome and its associated proteins

| Verma et al. [59] | Guerrero et al. [58] | Claverol et al. [60] | |

| Starting materials | Yeast | Yeast | Human erythrocytes |

| Ub tags | Rpt1-FLAG-(His)6 | Rpt5-(His)6-biotin | No tag |

| Purification strategies | Ab affinity column | Crosslinking and tandem affinity purification | Ab affinity column |

| MS methods | LC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS 36 proteasomal proteins & 64 | 2D gel & LC-MS/MS |

| #proteins identified | 24 | associated proteins | 14 |

7. Characterization of ubiquitin-binding proteins

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) are a collection of modular protein domains that non-covalently bind to ubiquitin [15]. UBDs are composed of 20–150 amino acid residues, which are structurally diverse and can be found in enzymes that catalyze ubiquitination or deubiquitination, or in Ub receptors that recognize mono-Ub or polyUb chains on modified substrates (Fig. 1). Numerous ubiquitin receptor proteins (>250 in human) have been identified by the method of Ub-affinity purification, yeast two-hybrid analysis, and bioinformatics prediction. For example, Russell and Wilkinson [65] used a synthesized non-hydrolyzable analogue of K29-linked polyubiquitin chain as affinity matrix to identify two binding partners, isopeptidase T and Ufd3, from yeast lysate. The result suggests that it is efficient to isolate some Ub-binding proteins using the affinity purification, although the binding affinity of UBDs is generally low, with the dissociation constant ranging from 2 to 750 μM [15]. To understand the regulation of ubiquitin pathways, it is important to determine the binding specificity between ubiquitin conjugates and Ub receptors. Mayor et al. [66] identified some potential ubiquitinated substrates that may be recognized by a Ub receptor Rpn10 by comparing the ubiquitinated proteome from wild-type yeast and Rpn10 deletion strain. This method has potential for mapping the Ub receptor-substrate networks in cells.

8. Investigation of ubiquitin-like protein pathways

All methods described above can be used to characterize the pathways of ubiquitin-like proteins with minor modifications, as exemplified by several cases. SUMO is the most studied ubiquitin-like protein that regulates a wide range of cellular events [18], evidenced by a large number of sumoylated proteins identified in more than ten large-scale studies (Table 3) [67–77]. For instance, Wohlschlegel et al. [69] used a nickel affinity purification procedure to isolate His-tagged SUMO-conjugates from yeast and identify 271 putative SUMO modified substrates. Although purified under denaturing condition, the contaminant proteins were found as many as 574 proteins in the negative control. To further reducing the co-purified proteins, Denison et al. [72] developed a double-affinity purification strategy to identify 250 sumoylated candidates.

Table 3.

Comparison of multiple analyses of proteins modified by a ubiquitin-like protein (SUMO-1, -2, -3/Smt3)

| Yeast | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Zhou et al. [64] | Denison et al. [69] | Hannich et al. [70] | Panse et al. [67] | Wohlschlegel et al. [66] | ||

| Tags | (His)6-FLAG-Smt3 | (His)6-FLAG-Smt3 | (His)6-FLAG-Tev-Smt3 | Protein A-Smt3 | (His)8-Smt3 | |

| Purification strategies | Denaturing nickel column & FLAG affinity capture | Denaturing nickel column & FLAG affinity capture | Denaturing nickel column & FLAG affinity capture | Native affinity purification | Denaturing nickel chromatography | |

| MS methods | GeLC-MS/MS | GeLC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | GeLC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | |

| #Protein identified | ~60 | 250 | 146 | 138 | 271 | |

| #Proteins with identified modification sites | 7 (10 sites) | 6 (6 sites) | not available | not available | not available | |

| Mammalian cells | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Vertegaal et al. [68] | Zhao et al. [71] | Manza et al. [72] | Li et al. [65] | Li et al. [73] | Rosas-Acosta et al. [74] | |

| Tags | (His)6-SUMO-2 | HA-SUMO-1 | HA-SUMO-1 & -3 | Biotin-SUMO-1 | myc-(His)6-SUMO-2 & -3 | (His)6-S tag-SUMO-1 & -3 |

| Purification strategies | Nuclei isolation & denaturing nickel chromatography | denaturing Ab affinity chromatography | Native Ab affinity chromatography | Denaturing biotin affinity chromatography | Denaturing nickel chromatography | Denaturing nickel chromatography |

| MS methods | LC-MS/MS | GeLC-MS/MS | LC/LC-MS/MS | LC-MS/MS | LC-MS/MS | LC-MS/MS |

| #Protein identified | 8 | 21 | 54/38a | 21 | 14/13b | 62/34a |

| #Proteins with identified modification sites | not available | not available | not available | not available | not available | not available |

the numbers of identified proteins that are potentially modified by SUMO-1 and SUMO-3, respectively

the numbers of identified proteins that are potentially modified by SUMO-2 and SUMO-3, respectively

Slightly different from ubiquitin, SUMO is conjugated to the lysine residue within a consensus motif ϕKxD/E where ϕ is a hydrophobic residue (most commonly leucine, isoleucine and valine) and x is any amino acid [78]. The modification sites can also be determined by tandem mass spectrometry. Compared to the GG tag trimmed from Ub, the SUMO tag on substrates after trypsin digestion is substantially longer (EQIGG, 484.2282 Da). The long tag might hamper its detection in the proteomic analysis, as much fewer sumoylated residues have been identified in the studies listed in Table 3. The analysis of the modification sites may be facilitated by shortening the tag to GG through genetic mutation [79]. The proteomics strategy has also been utilized to investigate other ubiquitin-like proteins, such as interferon stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) [80–82] and Nedd8 [76].

9. Concluding remarks

The application of modern mass spectrometry has quickly expanded the territory of proteins modified by the ubiquitin family. However, many proteins of interest may escape the detection by the current proteomics technologies. Ub and Ubls modifications are highly dynamic and the profiles of some modified substrates vary dramatically throughout the cell cycle and in response to various stimuli. So a significant hurdle in identifying these substrates is believed to their low abundance because in many cases only a small fraction of a substrate is thought to be modified at a given time under a certain condition. This problem will be alleviated by the rapid progress in developing more sensitive proteomics platforms. More importantly, the maturation of quantitative MS tools will greatly aid the differentiation of target proteins from background proteins and address how the modifications of these substrates change in various cellular conditions and genetic backgrounds.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Steven Gygi for discussion and data sharing. This work was supported in part by NIH grants DK069580 and AG025688 to J.P..

Abbreviations

- MS

mass spectrometry

- Ub

ubiquitin

- AQUA

absolute quantification

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry

- SRM

selective reaction monitoring

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varshavsky A. Regulated protein degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:283–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman AM. Themes and variations on ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:169–78. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:141–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciechanover A, Ben-Saadon R. N-terminal ubiquitination: more protein substrates join in. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:103–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadwell K, Coscoy L. Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2005;309:127–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng J, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Cheng D, Marsischky G, Roelofs J, Finley D, Gygi SP. A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:921–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson KD. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination: targeting of proteins for degradation by the proteasome. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:141–8. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M. Mechanism and function of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semple CA. The comparative proteomics of ubiquitination in mouse. Genome Res. 2003;13:1389–94. doi: 10.1101/gr.980303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickart CM, Fushman D. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:610–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:610–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hofmann K. When ubiquitin meets ubiquitin receptors: a signalling connection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:491–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper JW, Schulman BA. Structural complexity in ubiquitin recognition. Cell. 2006;124:1133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M. Modification of Proteins by Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-Like Proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503. Jun 5 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng J, Gygi SP. Proteomics: the move to mixtures. J Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:1083–91. doi: 10.1002/jms.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yates JR., 3rd Mass spectral analysis in proteomics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:297–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.111502.082538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denison C, Kirkpatrick DS, Gygi SP. Proteomic insights into ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkpatrick DS, Denison C, Gygi SP. Weighing in on ubiquitin: the expanding role of mass-spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:750–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng J, Cheng D. Proteomic analysis of ubiquitin conjugates in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:367–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tagwerker C, Flick K, Cui M, Guerrero C, Dou Y, Auer B, Baldi P, Huang L, Kaiser P. A Tandem Affinity Tag for Two-step Purification under Fully Denaturing Conditions: Application in Ubiquitin Profiling and Protein Complex Identification Combined with in vivo Cross-Linking. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:737–748. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500368-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkpatrick DS, Weldon SF, Tsaprailis G, Liebler DC, Gandolfi AJ. Proteomic identification of ubiquitinated proteins from human cells expressing His-tagged ubiquitin. Proteomics. 2005;5:2104–11. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M, Hatakeyama S, Oyamada K, Oda Y, Nishimura T, Nakayama KI. Large-scale analysis of the human ubiquitin-related proteome. Proteomics. 2005;5:4145–51. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasilescu J, Smith JC, Ethier M, Figeys D. Proteomic analysis of ubiquitinated proteins from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells by immunoaffinity purification and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2192–200. doi: 10.1021/pr050265i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gururaja T, Li W, Noble WS, Payan DG, Anderson DC. Multiple functional categories of proteins identified in an in vitro cellular ubiquitin affinity extract using shotgun peptide sequencing. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:394–404. doi: 10.1021/pr034019n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Hayami R, Wu W, Nishikawa T, Nishikawa H, Okuda Y, Ogata H, Fukuda M, Ohta T. Nucleophosmin/B23 is a candidate substrate for the BRCA1-BARD1 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30919–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kus B, Gajadhar A, Stanger K, Cho R, Sun W, Rouleau N, Lee T, Chan D, Wolting C, Edwards A, Bosse R, Rotin D. A high throughput screen to identify substrates for the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29470–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hitchcock AL, Auld K, Gygi SP, Silver PA. A subset of membrane-associated proteins is ubiquitinated in response to mutations in the endoplasmic reticulum degradation machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135500100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marotti LA, Jr, Newitt R, Wang Y, Aebersold R, Dohlman HG. Direct identification of a G protein ubiquitination site by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5067–74. doi: 10.1021/bi015940q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren MR, Parker CE, Mocanu V, Klapper D, Borchers CH. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry of model peptides Reveals diagnostic fragment ions for protein ubiquitination. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:429–37. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper HJ, Heath JK, Jaffray E, Hay RT, Lam TT, Marshall AG. Identification of sites of ubiquitination in proteins: a fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry approach. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6982–8. doi: 10.1021/ac0401063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D, Cotter RJ. Approach for determining protein ubiquitination sites by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:1458–66. doi: 10.1021/ac048834d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JS, Hong US, Lee TH, Yoon SK, Yoon JB. Mass spectrometric analysis of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 ubiquitination mediated by cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 2. Proteomics. 2004;4:3376–82. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol Cell. 2006;22:245–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catic A, Collins C, Church GM, Ploegh HL. Preferred in vivo ubiquitination sites. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3302–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Context of multiubiquitin chain attachment influences the rate of Sic1 degradation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1435–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatakeyama S, Yada M, Matsumoto M, Ishida N, Nakayama KI. U box proteins as a new family of ubiquitin-protein ligases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33111–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang F, Kirkpatrick D, Jiang X, Gygi S, Sorkin A. Differential regulation of EGF receptor internalization and degradation by multiubiquitination within the kinase domain. Mol Cell. 2006;21:737–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chau V, Tobias JW, Bachmair A, Marriott D, Ecker DJ, Gonda DK, Varshavsky A. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243:1576–83. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson ES, Ma PC, Ota IM, Varshavsky A. A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17442–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koegl M, Hoppe T, Schlenker S, Ulrich HD, Mayer TU, Jentsch S. A novel ubiquitination factor, E4, is involved in multiubiquitin chain assembly. Cell. 1999;96:635–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saeki Y, Tayama Y, Toh-e A, Yokosawa H. Definitive evidence for Ufd2-catalyzed elongation of the ubiquitin chain through Lys48 linkage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:840–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spence J, Sadis S, Haas AL, Finley D. A ubiquitin mutant with specific defects in DNA repair and multiubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1265–73. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnason T, Ellison MJ. Stress resistance in Saccharomyces ceRevisiae is strongly correlated with assembly of a novel type of multiubiquitin chain. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7876–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloper-Mould KE, Jemc JC, Pickart CM, Hicke L. Distinct functional surface regions on ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30483–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varadan R, Assfalg M, Haririnia A, Raasi S, Pickart C, Fushman D. Solution conformation of Lys63-linked di-ubiqutin chain provides clues to functional diversity of polyubiquitin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7055–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6940–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirkpatrick DS, Hathaway NA, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Rush J, Finley D, King RW, Gygi SP. Quantitative analysis of in vitro ubiquitinated cyclin B1 Reveals complex chain topology. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:700–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu P, Cheng D, Duong DM, Rush J, Roelofs J, Finley D, Peng J. A proteomic strategy for quantifying polyubiquitin chain topologies. Israel J Chem. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borodovsky A, Ovaa H, Kolli N, Gan-Erdene T, Wilkinson KD, Ploegh HL, Kessler BM. Chemistry-based functional proteomics Reveals novel members of the deubiquitinating enzyme family. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1149–59. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.BalakiRev MY, Tcherniuk SO, Jaquinod M, Chroboczek J. Otubains: a new family of cysteine proteases in the ubiquitin pathway. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:517–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu K, Yamoah K, Dolios G, Gan-Erdene T, Tan P, Chen A, Lee CG, Wei N, Wilkinson KD, Wang R, Pan ZQ. DEN1 is a dual function protease capable of processing the C terminus of Nedd8 and deconjugating hyper-neddylated CUL1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28882–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gan-Erdene T, Nagamalleswari K, Yin L, Wu K, Pan ZQ, Wilkinson KD. Identification and characterization of DEN1, a deneddylase of the ULP family. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28892–900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hemelaar J, Borodovsky A, Kessler BM, Reverter D, Cook J, Kolli N, Gan-Erdene T, Wilkinson KD, Gill G, Lima CD, Ploegh HL, Ovaa H. Specific and covalent targeting of conjugating and deconjugating enzymes of ubiquitin-like proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:84–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.84-95.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ovaa H, Kessler BM, Rolen U, Galardy PJ, Ploegh HL, Masucci MG. Activity-based ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) profiling of virus-infected and malignant human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rolen U, Kobzeva V, Gasparjan N, Ovaa H, Winberg G, Kisseljov F, Masucci MG. Activity profiling of deubiquitinating enzymes in cervical carcinoma biopsies and cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:260–9. doi: 10.1002/mc.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guerrero C, Tagwerker C, Kaiser P, Huang L. An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:366–78. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verma R, Chen S, Feldman R, Schieltz D, Yates J, Dohmen J, Deshaies RJ. Proteasomal proteomics: identification of nucleotide-sensitive proteasome-interacting proteins by mass spectrometric analysis of affinity-purified proteasomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3425–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Claverol S, Burlet-Schiltz O, Girbal-Neuhauser E, Gairin JE, Monsarrat B. Mapping and structural dissection of human 20 S proteasome using proteomic approaches. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:567–78. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200030-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt M, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Finley D. Proteasome-associated proteins: regulation of a proteolytic machine. Biol Chem. 2005;386:725–37. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Russell NS, Wilkinson KD. Identification of a novel 29-linked polyubiquitin binding protein, Ufd3, using polyubiquitin chain analogues. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4844–54. doi: 10.1021/bi035626r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mayor T, Lipford JR, Graumann J, Smith GT, Deshaies RJ. Analysis of polyubiquitin conjugates Reveals that the Rpn10 substrate receptor contributes to the turnover of multiple proteasome targets. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:741–51. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400220-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H. Global analyses of sumoylated proteins in Saccharomyces ceRevisiae. Induction of protein sumoylation by cellular stresses. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32262–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404173200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li T, Evdokimov E, Shen RF, Chao CC, Tekle E, Wang T, Stadtman ER, Yang DC, Chock PB. Sumoylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, zinc finger proteins, and nuclear pore complex proteins: a proteomic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8551–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402889101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR., 3rd Global analysis of protein sumoylation in saccharomyces ceRevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Panse VG, Hardeland U, Werner T, Kuster B, Hurt E. A proteome-wide approach identifies sumolyated substrate proteins in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vertegaal AC, Ogg SC, Jaffray E, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. A proteomic study of SUMO-2 target proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33791–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Denison C, Rudner AD, Gerber SA, Bakalarski CE, Moazed D, Gygi SP. A proteomic strategy for gaining insights into protein sumoylation in yeast. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:246–54. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400154-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hannich JT, Lewis A, Kroetz MB, Li SJ, Heide H, Emili A, Hochstrasser M. Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces ceRevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4102–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao Y, Kwon SW, Anselmo A, Kaur K, White MA. Broad spectrum identification of cellular small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) substrate proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20999–1002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manza LL, Codreanu SG, Stamer SL, Smith DL, Wells KS, Roberts RL, Liebler DC. Global shifts in protein sumoylation in response to electrophile and oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1706–15. doi: 10.1021/tx049767l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li T, Santockyte R, Shen RF, Tekle E, Wang G, Yang DC, Chock PB. A general approach for investigating enzymatic pathways and substrates for ubiquitin-like modifiers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A universal strategy for proteomic studies of SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodriguez MS, Dargemont C, Hay RT. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12654–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knuesel M, Cheung HT, Hamady M, Barthel KK, Liu X. A method of mapping protein sumoylation sites by mass spectrometry using a modified small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1) and a computational program. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1626–36. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500011-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dao CT, Zhang DE. ISG15: a ubiquitin-like enigma. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2701–22. doi: 10.2741/1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giannakopoulos NV, Luo JK, Papov V, Zou W, Lenschow DJ, Jacobs BS, Borden EC, Li J, Virgin HW, Zhang DE. Proteomic identification of proteins conjugated to ISG15 in mouse and human cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhao C, Denison C, Huibregtse JM, Gygi S, Krug RM. Human ISG15 conjugation targets both IFN-induced and constitutively expressed proteins functioning in diverse cellular pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504754102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]