Abstract

A nosocomial pyogenic liver abscess caused by an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate presented in a man with adenocarcinoma of the stomach. The K. pneumoniae strain isolated from blood and liver aspirate cultures after antibiotic therapy for recurrent bacteremia was resistant to all extended-spectrum beta-lactams except imipenem and differed from K. pneumoniae strains causing community-acquired liver abscesses.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old man with adenocarcinoma of the stomach received a radical gastrectomy in 2003 and then 11 courses of intensive chemotherapy with fluorouracil, calcium folinate, and oxaliplatin for tumor metastasis to the liver and peritoneum. In July 2005, he was admitted to the Tri-Service General Hospital for treatment of oral candidiasis associated with shaking chills, spiking fever, and abdominal fullness. Initially, intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam and oral fluconazole were given. Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, and Fusobacterium varium were isolated from two sets of blood cultures. The E. coli strain was susceptible to all cephalosporins but was resistant to ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Cefpirome and metronidazole were administered 5 days later, but the patient's intermittent spiking fever persisted. A blood culture disclosed Enterococcus faecium and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Gentamicin was added to the patient's treatment regimen. On day 14, he again developed spiking fever with pain over the right upper quadrant of his abdomen. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed a 4-cm hypodense lesion over segment 6 of the liver (Fig. 1). Percutaneous drainage was performed and pus was aspirated. The liver biopsy revealed a massive necrosis with inflammatory cells in liver tissue. An extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain, detected by double-disk screening and confirmatory tests based on CLSI recommendations, was isolated from cultures of blood and pus aspirated from the liver. The K. pneumoniae strain was resistant to all cephalosporins and aminoglycosides, but it was sensitive to imipenem. The MICs of the antimicrobial agents were determined by Etest by using the interpretive standards based on CLSI recommendations. The MICs were as follows (6): ceftazidime, 256 μg/ml; ceftriaxone, 256 μg/ml; cefepime, 128 μg/ml; cefoxitin, 128 μg/ml; gentamicin, 96 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin, 32 μg/ml; and imipenem, 0.75 μg/ml. The AmpC disk test was negative for the detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases (data was not shown) (1). The capsular serotype was non-K1/K2 by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis, and the phenotype was nonmucoid (9, 10). PCR for the magA gene was negative (7). In this case, the same antibiogram and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns were demonstrated for isolates from blood and pus aspirated from the liver (data not shown). PFGE demonstrated that the strain had PFGE patterns completely different from those of strains from patients with community-acquired liver abscesses and nosocomially acquired ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae bacteremia (Fig. 2) (20). Although the patient's clinical symptoms and signs improved after treatment with imipenem for 6 weeks, he died of progressive carcinomatosis with multiple-organ failure 2 months later.

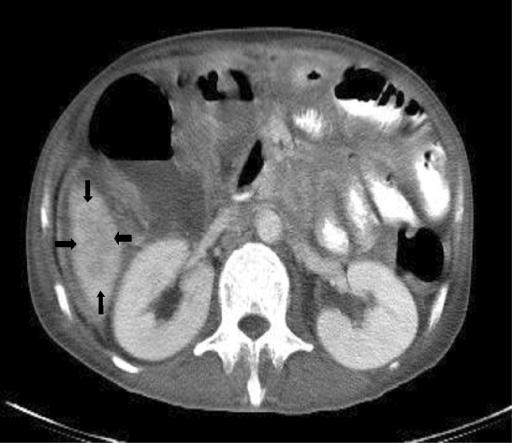

FIG. 1.

Computed tomography of the abdomen showing a hypodense lesion (arrows) about 4 cm over the right lobe of the liver.

FIG. 2.

(A) Dendrogram based on the PFGE results for eight clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae. The strains were clustered by the unweighted pair group method with using arithmetic averages (strains 1, 3, 13, and 23 were isolated from community-acquired liver abscesses, serotype K1; strains 33, 37, and 38 were isolated from nosocomial bloodstream infections of ESBL-producing non-K1/K2 strains; strain I, the strain from the present study). (B) PFGE. The image shows the different molecular clones of K. pneumoniae strains isolated from community-acquired liver abscesses and nosocomial bloodstream infections and the strain from the present study.

Discussion.

This is the first report of a nosocomial liver abscess caused by an ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strain after intensive chemotherapy for carcinoma of the stomach and prolonged antibiotic treatment for recurrent bacteremia. K. pneumoniae has been emerging as the leading cause of community-acquired pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan and the United States (2, 3, 8, 11, 14). Different clonal populations of K. pneumoniae cause community-acquired pyogenic liver abscesses (4, 5). Serotype K1/K2 accounts for 78% of isolates, and the non-K1/K2 serotype accounts for 22% (9). ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains are one of the most frequent causes of nosocomial pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, urinary tract infections, and primary bacteremia (13). The prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains as nosocomial pathogens is increasing worldwide (13, 15, 19). Information regarding K. pneumoniae-associated infections is summarized in Table 1 (3, 9, 12-14, 17). The newly emerged community-acquired K. pneumoniae strains that cause liver abscesses have been associated with more septic metastatic complications and low mortality rates, whereas nosocomial K. pneumoniae strains, including non-ESBL-producing and ESBL-producing strains, have been associated with less septic metastatic complications and high rates of mortality. These community-acquired and nosocomial infections have very different presentations.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Klebsiella pneumoniae infectiona

| Diagnosis | Mean age (yr [SD or range]) | S/S | Serotype, proportion of isolates | Hepatobiliary-GI tract abnormality rate (%) | DM rate (%) | Metastatic complication, proportion of patients | Mortality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community-acquired K. pneumoniae bacteremiab | 61.2 (±15.7) | Fever | K1, 30%; K2, 6%; non-K1/K2, 64% | 13 | 49 | Not found except in combination with liver abscess | 14 |

| Community-acquired K. pneumoniae liver abscess, Taiwanc | 56.4 (34-78) | Fever, RUQ pain | K1, 64%; K2, 14%; non-K1/K2, 22% | 8.2 | 78.4 | Endophthalmitis, 10.4%; other site metastasis, 3% | 6 |

| Community-acquired K. pneumoniae liver abscess, United Statesd | 56.4 (25-90) | Fever, RUQ pain | NA | 43 | 15.2 | Not found | 2.5 |

| Nosocomially acquired K. pneumoniae bacteremiab | 59.2 (±20.7) | Fever, jaundice, leukopenia | K1, 14%; K2, 3%; non-K1/K2, 83% | 2 | 12 | Not found | 36 |

| Nosocomially acquired ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae bacteremiae | 58 (17-90) | Septic shock, pneumonia, UTI | NA | 13.1 | 15.2 | Not found | 23.5 |

| Nosocomially acquired ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae liver abscessf | 48 | Fever, RUQ pain | Non-K1/K2 | Yes | No | Not found | 100 |

The availability of extended-spectrum cephalosporins has facilitated the treatment of severe infections caused by gram-negative bacteria. However, the increasing rate of use of these agents has been associated with the emergence of resistant bacterial strains, such as those that produce different SHV- or TEM-derived ESBLs (12, 16).

A well-known virulence factor of K. pneumoniae strains associated with liver abscesses is the capsular polysaccharide serotype (such as K1 and K2) (9). However, the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strain in our case was magA negative and non-K1/K2. The PFGE pattern of genomic DNA from the eight K. pneumoniae strains isolated from patients with community-acquired liver abscesses (serotype K1, n = 4), nosocomial bacteremias (K1 and non-K1/K2 [i.e., K54 and K55]), and the present case were different; and the genetic dendrogram showed that the strains had low levels of similarity. Further study is needed to determine whether other virulence factors, such as the strain of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, are important.

Intensive chemotherapy and the prolonged use of antibiotics put patients with intestinal tract tumors, hepatobiliary tract tumors, or intra-abdominal carcinomatosis at risk for infection by opportunistic pathogens and recurrent bacteremia (18). However, selective antibiotic pressure may play a role in the selection of ESBL-producing strains (13). In our case, a nosocomially acquired liver abscess caused by an ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strain was selected for by prolonged broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment.

In conclusion, the strain of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae that caused a nosocomially acquired liver abscess in our case differed from the strains that cause community-acquired liver abscesses with respect to capsular serotype, antibiogram pattern, and PFGE pattern. The more judicious use of antibiotics is recommended to decrease the rates of bacterial resistance and to slow the emergence of resistant bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Tri-Service General Hospital (grants TSGH-C95-50 and TSGH-C95-51) and the National Science Council (grant NSC 95-2314-B-016-013).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black, J. A., E. S. Moland, and K. S. Thomson. 2005. AmpC disk test for detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae lacking chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3110-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan, K. S., C. M. Chen, K. C. Cheng, C. C. Hou, H. J. Lin, and W. L. Yu. 2005. Pyogenic liver abscess: a retrospective analysis of 107 patients during a 3-year period. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 58:366-368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, F. Y., and M. Y. Chou. 1995. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae pathogens. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 94:232-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, S. C., C. T. Fang, P. R. Hsueh, Y. C. Chen, and K. T. Luh. 2000. Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing liver abscess in Taiwan. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng, H. P., F. Y. Chang, C. P. Fung, and L. K. Siu. 2002. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in Taiwan is not caused by a clonal spread strain. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 35:85-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: fifteenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 7.Fang, C. T., Y. P. Chuang, C. T. Shun, S. C. Chang, and J. T. Wang. 2004. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J. Exp. Med. 199:697-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang, F. C., N. Sandler, and S. J. Libby. 2005. Liver abscess caused by magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:991-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung, C. P., F. Y. Chang, S. C. Lee, B. S. Hu, B. I. Kuo, C. Y. Liu, M. Ho, and L. K. Siu. 2002. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut 50:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung, C. P., B. S. Hu, F. Y. Chang, S. C. Lee, B. I. Kuo, M. Ho, L. K. Siu, and C. Y. Liu. 2000. A 5-year study of the seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae: high prevalence of capsular serotype K1 in Taiwan and implication for vaccine efficacy. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2075-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lederman, E. R., and N. F. Crum. 2005. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100:322-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterson, D. L. 2001. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: the European experience. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 14:697-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterson, D. L., W. C. Ko, G. A. Von, S. Mohapatra, J. M. Casellas, H. Goossens, L. Mulazimoglu, G. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, R. A. Bonomo, L. B. Rice, M. M. Wagener, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2004. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in nosocomial Infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 140:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahimian, J., T. Wilson, V. Oram, and R. S. Holzman. 2004. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1654-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiappa, D. A., M. K. Hayden, M. G. Matushek, F. N. Hashemi, J. Sullivan, K. Y. Smith, D. Miyashiro, J. P. Quinn, R. A. Weinstein, and G. M. Trenholme. 1996. Ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli bloodstream infection: a case-control and molecular epidemiologic investigation. J. Infect. Dis. 174:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siu, L. K. 2002. Antibiotics: action and resistance in gram-negative bacteria. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 35:1-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsay, R. W., L. K. Siu, C. P. Fung, and F. Y. Chang. 2002. Characteristics of bacteremia between community-acquired and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: risk factor for mortality and the impact of capsular serotypes as a herald for community-acquired infection. Arch. Intern. Med. 162:1021-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weng, S. W., J. W. Liu, W. J. Chen, and P. W. Wang. 2005. Recurrent Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in a diabetic patient followed by Streptococcus bovis endocarditis—occult colon tumor plays an important role. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 58:70-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiener, J., J. P. Quinn, P. A. Bradford, R. V. Goering, C. Nathan, K. Bush, and R. A. Weinstein. 1999. Multiple antibiotic-resistant Klebsiella and Escherichia coli in nursing homes. JAMA 281:517-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu, T. L., L. K. Siu, L. H. Su, T. L. Lauderdale, F. M. Lin, H. S. Leu, T. Y. Lin, and M. Ho. 2001. Outer membrane protein change combined with co-existing TEM-1 and SHV-1 beta-lactamases lead to false identification of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]