Abstract

No commercial viral load assay has yet been approved for use for measurement of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) RNA levels in plasma. We assessed the performance of the NucliSens EasyQ (version 1.1) assay (EasyQ; bioMérieux, Boxtel, The Netherlands) to quantify HIV-2 viremia. A viral stock was prepared from an HIV-2 (subtype A)-infected patient. Culture supernatant was subjected to viral particle counting by electron microscopy. Serial dilutions of the viral stock were made in HIV-negative plasma and were used to test EasyQ for its sensitivity, linearity, and reproducibility. RNA was quantified by the NucliSens EasyQ (version 1.1) assay. Plasma samples from 75 HIV-2-infected patients were further tested. EasyQ was able to quantify HIV-2 RNA in a reproducible manner. Overall, estimates of the number of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml obtained with EasyQ were lower than those obtained by electron microscopy; however, the differences were always less than 0.7 log (mean, 0.55 ± 0.19 log10). The assay showed good linearity (r2 = 0.964; P < 0.0001). The agreement between both measures was assessed by use of a Bland-Altman plot; the narrow limits (0.158 to 0.952), defined as the mean difference ± 2 standard deviations, indicated good agreement. The reproducibility was also good, since the between-run coefficients of variation were 1.49, 3.60, and 12.25% for samples containing 6.30, 4.30, and 2.30 log10 HIV-2 RNA copies/ml, respectively. HIV-2 RNA was detected in 34 of 75 (45%) plasma specimens (mean, 2.72 log RNA copies/ml; range, 1.74 to 4.11 log RNA copies/ml); the rest of the specimens were considered to have undetectable viremia. A negative correlation was found between the number of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml and CD4 counts. In summary, EasyQ was shown to be reliable for the measurement of plasma HIV-2 subtype A RNA levels and may be a feasible tool for routine clinical monitoring of HIV-2 subtype A-infected patients.

Quantification of plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA is critical for the adequate management of infected individuals. Although several commercial molecular tests have been developed and are in use for the measurement of plasma HIV type 1 (HIV-1) RNA levels, none has yet been approved for use for the measurement of HIV-2 RNA levels. In the absence of an approved commercial assay for the determination of the HIV-2 load, a few research laboratories have developed distinct in-house methods (1, 3, 8, 13, 16). None of these techniques, however, is widely available for routine clinical use.

The number of individuals infected with HIV-2 worldwide is much lower than the number infected with HIV-1. These individuals are mainly concentrated in West Africa and to a lesser extent in Portugal, Brazil, and Mozambique. Only HIV-2 subtypes A and B are prevalent and are found outside West Africa, and subtypes C to G correspond to strains found in one or two individuals in Africa (5). In Spain, 80% of the reported cases correspond to subtype A; similar results have been found in other European countries (7). HIV-2 infection has been associated with significantly lower viral loads than HIV-1 infection (8, 10, 13), which may explain the slower rate of progression to AIDS for individuals infected with HIV-2 and the lower transmission efficiency of HIV-2 (11, 17). However, over time, a substantial proportion of carriers develop profound CD4 depletion and therefore can benefit from antiretroviral therapy. At that time, measurement of the plasma HIV-2 RNA level is important for assessment of the efficacy of treatment and, eventually, for recognition of virological failure.

The Nuclisens EasyQ (version 1.1) assay (EasyQ; bioMérieux) was originally developed and commercialized for the quantification of different HIV-1 group M viruses (9). In vitro experiments, however, soon demonstrated that the technique was also able to detect HIV-2 RNA. We assessed the performance of the NucliSens EasyQ (version 1.1) assay for the quantitative measurement of HIV-2 RNA in both viral isolates and clinical specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral stocks.

Cell-free viral stocks were prepared from one HIV-2 subtype A-infected patient. Viruses were isolated by cocultivation of the patient's peripheral blood mononuclear cells and cells were drawn from seronegative donors, as described elsewhere (20). The production of viruses was measured by determination of the p24 antigen concentration with a commercial p24 antigen capture assay (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), following the manufacturer's instructions. Once high viral titers were reached, 1-ml aliquots of the supernatant were obtained, cleaned by centrifugation, and frozen. HIV-2 subtype assignment was established through DNA sequence analysis of the pol gene with the primers and conditions described elsewhere (6).

Viral particle count by electron microscopy.

Culture supernatants were subjected to viral particle counting by transmission electron microscopy. Briefly, polystyrene microspheres (5.68 × 1012 per ml; diameter, 0.202 ± 0.010 μm; Polysciences, Inc.) were added to 1 ml of culture supernatant to a final concentration of 1 × 109 spheres per ml. The mixture was ultracentrifuged in a Sorvall Discovery M120 microultracentrifuge (4°C, 38,000 rpm [89,000 × g] for 60 min). The resulting pellets were embedded in 1.5% agarose (Seakem GTG; FMC Corp.) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. After postfixation with osmium tetroxide, serial dehydration, and embedment in epoxy resin, ultrathin sections were obtained, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and evaluated in a Tecnai 12 electron microscope (FEI Co.) at 120 kV. Forty-one fields from different sections were photographed at ×8,900 magnification. The total numbers of viral particles and spheres in all fields were counted to assess the ratio of spheres to virions in the pellets.

Linearity panel.

Serial threefold dilutions of the concentrated viral stock suspension (2 × 105, 6 × 104, 2 × 104, 6 × 103, 2 × 103, 6 × 102, 2 × 102, and 1 × 102 RNA copies/ml) were made in HIV-negative plasma. Each dilution was tested in duplicate in three separate runs.

Reproducibility panel.

Five 10-fold dilutions of the viral stock suspension were made in HIV-negative plasma; these corresponded to 2 × 106, 2 × 105, 2 × 104, 2 × 103, and 2 × 102 RNA copies/ml. Each sample was tested in triplicate in six separate assays.

Clinical specimens.

Frozen plasma drawn from 75 different HIV-2-infected patients was tested. Four patients were infected with HIV-2 subtype B, and the rest carried subtype A. Thirty-five (46.6%) were receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Quantification of HIV-2 RNA.

RNA was extracted from each sample by using the Nuclisens extractor (bioMérieux), and the Nuclisens EasyQ (version 1.1) assay (bioMérieux) was used to quantify HIV-2 RNA molecules, following the manufacturer's instructions. The Nuclisens EasyQ assay is a nucleic acid-specific amplification method coupled with real-time detection with molecular beacons. It was designed to detect gag RNA targets from HIV-1 group M viruses (19). EasyQ results are given in RNA IU/ml, which is equivalent to the number of RNA copies/ml. Therefore, to simplify the reading of this article, we will use the number of RNA copies/ml throughout the text.

Statistical analyses.

For the linearity panel, a linear regression analysis was performed on log10-transformed data, and the correlation coefficient was calculated. The extent of agreement between the two measurements (EasyQ and electron microscopy) was assessed by the Bland and Altman method (4). For the reproducibility panel, means, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation (CV) were calculated. In clinical samples, Student's t test was used for analysis of viral loads and CD4 categories.

RESULTS

HIV-2 RNA detection and quantification.

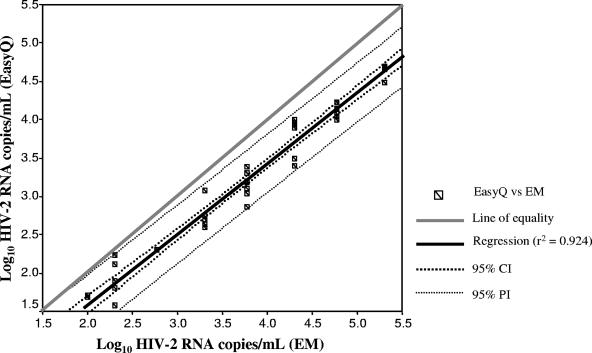

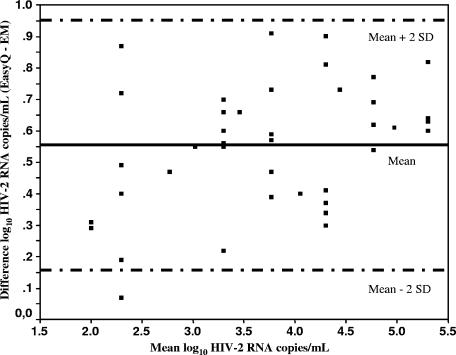

EasyQ was able to detect and quantify HIV-2 RNA subtype A in a reproducible manner. Overall, the HIV-2 RNA copy numbers obtained by EasyQ were lower than the number of RNA copies/ml estimated by using the particle count method (assuming that there are two genomic RNA copies per virion). However, the differences were less than 0.7 log10 in all instances, and the mean difference was 0.55 ± 0.19 log10. Figure 1 shows the plot for linearity. The square of the correlation coefficient between values given by EasyQ and the estimates of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml given by electron microscopy was 0.964 (P < 0.0001). The fitted regression line was described by the equation y = 0.924x − 0.269, which is close to the ideal line of equality (slope = 1, intercept = 0). The agreement between both measures was assessed by use of a Bland-Altman plot, which compared the differences between the values provided by both methods against their means by using log10-transformed data (Fig. 2). The limits of agreement, defined as the mean difference ± 2 standard deviations, were 0.158 to 0.952. These narrow limits confirm the good agreement between values obtained by EasyQ and the estimates of the number of HIV-2 RNA copies obtained from particle counts. In fact, only one measurement was beyond the limits of agreement.

FIG. 1.

Scatter plot of the log10 numbers of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml determined by EasyQ and electron microscopy (EM) for threefold dilutions of the HIV-2 viral stock. CI, confidence interval; PI, predictive interval.

FIG. 2.

Bland-Altman plot of the difference between EasyQ and electron microscopy (EM) values for the log10 numbers of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml against their means. The mean difference (solid line) ± 2 standard deviations (dashed lines) are shown.

Reproducibility and sensitivity.

EasyQ showed good reproducibility for HIV-2 RNA quantification. The CVs ranged from 0.66 to 8% in the within-run assay and from 1.49 to 12.25% in the between-run assay. The means, standard deviations, and CVs for the replicate tests are given in Table 1. The sensitivity, based on repeated testing, was 66% at the lowest concentration of the viral stock (100 copies/ml) and 100% at 200 copies/ml.

TABLE 1.

Reproducibility of Nuclisens EasyQ assaya

| Samplea log10 RNA copies/ml | Mean no. of log10 RNA copies/ml (SD) | CV (%)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Within run | Between run | ||

| 6.30 | 5.97 (0.09) | 0.66 | 1.49 |

| 5.30 | 4.70 (0.12) | 0.83 | 3.00 |

| 4.30 | 3.86 (0.12) | 1.76 | 3.60 |

| 3.30 | 3.10 (0.14) | 3.21 | 4.58 |

| 2.30 | 1.82 (0.22) | 8.00 | 12.25 |

The HIV-2 RNA sample concentration was determined by particle counting by electron microscopy.

The CV is shown for both within-run and between-run experiments for five different concentrations of the HIV-2 viral stock.

Clinical specimens.

The number of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml was quantified in 34 of 75 (45%) plasma specimens. The remaining samples were considered to have undetectable viremia. The mean value for the positive samples was 2.72 log10 HIV-2 RNA copies/ml (range, 1.74 to 4.11 log10 HIV-2 RNA copies/ml). Among the subset of samples with detectable HIV-2 RNA, the lowest values were seen in antiretroviral treatment-naive individuals (mean, 2.45 log RNA copies/ml; range, 2 to 3.53 log RNA copies/ml).

An inverse correlation between the number of HIV-2 RNA copies/ml and the CD4 counts (r = −0.325; P = 0.004, Pearson's correlation) was found. The mean log10 HIV-2 RNA values were 2.45 for patients with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/μl and 1.96 for patients with CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/μl (P = 0.003). Moreover, the plasma HIV-2 RNA levels were also lower for the subset of patients with CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/μl than for subjects with CD4 counts between 200 and 500 cells/μl; however, it did not reach significance (1.85 and 2.10 log10 RNA copies/ml, respectively; P = 0.134).

The majority of antiretroviral treatment-naive individuals had CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/μl (29/40; 72.5%) and were clinically asymptomatic. Overall, 70% (28 of 40) of them had undetectable plasma viremia. In contrast, 21 of 35 (60%) of the patients receiving antiretroviral therapy showed detectable plasma viremia (mean, 2.87 log10 HIV-2 RNA copies/ml; range, 1.74 to 4.11 log10 HIV-2 RNA copies/ml). Accordingly, 24 of 35 (68%) of antiretroviral treatment-experienced patients had CD4 counts less than 200 cells/μl. In the series of patients studied, the majority of patients HIV-2 carried subtype A and only four patients carried HIV-2 subtype B; two of the latter four patients were drug treatment naive and had undetectable viremia and CD4 counts less than 500 cells/μl. The other two subjects were receiving antiretroviral therapy, although one of these subjects showed detectable plasma HIV-2 viremia.

DISCUSSION

The lack of a commercially available assay for measurement of plasma HIV-2 viremia has challenged the monitoring of the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-2-infected individuals. For this reason, the recognition that one assay originally developed and already approved for use for the measurement of the viral load in HIV-1 carriers may be equally valid for the quantification of HIV-2 viremia is of importance. The results of this evaluation provide acceptable confidence for the use of the Nuclisens EasyQ assay in clinical settings to monitor plasma viremia in HIV-2-infected individuals. Overall, our results showed a good correlation between the values obtained by the Nuclisens EasyQ assay and the number of HIV-2 RNA copies estimated in an HIV-2 viral stock. Although the values obtained by EasyQ tended to be a bit lower than the estimates of the numbers of HIV-2 RNA copies in the stock dilutions, the mean differences were about 0.5 log, which is within the acceptable variability for plasma viral load results. It should be noted, however, that EasyQ was optimized for the quantification of HIV-1 RNA molecules. Thus, the primers and probes might not detect HIV-2 RNA as accurately as they detect HIV-1 RNA, which might account for the observed difference. The agreement between EasyQ results and the stock control values was also within acceptable limits. Furthermore, the reproducibility (CV) of the EasyQ values was good in both the intra-assay and the interassay experiments.

The detection limit was set to 200 copies/ml, which might be a little high, particularly since half of the HIV-2-infected clinical samples tested were considered to have undetectable viremia. One way to improve the sensitivity of the assay without compromising its accuracy could be the use of a first ultracentrifugation step with a large volume of plasma. A further limitation of our evaluation of EasyQ is that the specificity was not examined. It should be highlighted that EasyQ was originally developed to measure HIV-1, and therefore, the results for patients coinfected with HIV-1 and HIV-2 may be difficult to interpret, as was recently pointed out for a dually infected patient receiving antiretroviral therapy who showed a CD4-viral load disconnect (15). Thus, our validation study applies only to HIV-2-monoinfected individuals. Finally, EasyQ has been validated only for subtype A because of a lack of a well-quantified HIV-2 subtype B viral standard and because we mainly examined HIV-2 subtype A-infected clinical specimens. Although the amount of HIV-2 RNA recognized in the few patients carrying subtype B inversely correlated with their CD4 cell counts and clinical symptoms, further studies with a larger panel of HIV-2 subtype B-infected samples are needed to validate the performance of EasyQ with subjects infected with different HIV-2 variants.

In clinical specimens the HIV-2 viral load values were lower than those observed in specimens infected with HIV-1, and the rate of positivity was 45%. Similar results have been reported by the use of other techniques for measurement of HIV-2 RNA levels with cutoffs between 100 and 250 copies/ml (2, 8, 13, 18). It is noteworthy that low HIV-2 RNA levels correlated with higher CD4 cell counts and a lack of clinical symptoms. A large proportion of HIV-2-infected patients receiving antiretroviral treatment did not show complete suppression of the viral load, which was in agreement with their poor CD4 status in most instances. This relatively high proportion of virological failures in HIV-2-infected individuals has already been underlined in other studies which have tested HIV-2-infected patients receiving treatment (1, 12, 14). The lack of means for the identification of virological failure resulted in a delay to the time of recognition of treatment failure until clinical symptoms and/or disease progression was apparent (15). It is hoped that this uncertainty might be solved by periodically monitoring the viral load in patients receiving treatment, as is done for HIV-1-infected individuals. Our results support the use of the Nuclisens EasyQ assay as a reasonable option for HIV-2 viral load testing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Oosterlaken and Frank Simon (BioMérieux) for providing the Nuclisens EasyQ (version 1.1) kits for this study and for helpful technical information.

This work was partly supported by Fundación IES, Red de Investigación en Sida (grants G03/173, FIPSE 36483/05, and FIS CP05/00300).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adje-Toure, C., R. Cheingsong, J. Garcia-Lerma, S. Eholie, M. Borget, J. Bouchez, R. Otten, C. Maurice, M. Sassan-Morokro, R. Ekpini, M. Nolan, T. Chorba, W. Heneine, and J. Nkengasong. 2003. Antiretroviral therapy in HIV-2-infected patients: changes in plasma viral load, CD4+ cell counts, and drug resistance profiles of patients treated in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS 17:S49-S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariyoshi, K., S. Jaffar, A. Alabi, N. Berry, M. Schim van der Loeff, S. Sabally, P. N′Gom, T. Corrah, R. Tedder, and H. Whittle. 2000. Plasma RNA viral load predicts the rate of CD4 T cell decline and death in HIV-2-infected patients in West Africa. AIDS 14:339-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry, N., K. Ariyoshi, S. Jaffar, S. Sabally, T. Corrah, R. Tedder, and H. Whittle. 1998. Low peripheral blood viral HIV-2 RNA in individuals with high CD4 percentage differentiates HIV-2 from HIV-1 infection. J. Hum. Virol. 1:457-468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bland, J., and D. Altman. 1986. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet i:307-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Z., A. Luckay, D. L. Sodora, P. Telfer, P. Reed, A. Gettie, J. M. Kanu, R. F. Sadek, J. Yee, D. D. Ho, L. Zhang, and P. A. Marx. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) seroprevalence and characterization of a distinct HIV-2 genetic subtype from the natural range of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J. Virol. 71:3953-3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cilla, G., B. Rodes, E. Perez-Trallero, J. Arrizabalaga, and V. Soriano. 2001. Molecular evidence of homosexual transmission of HIV type 2 in Spain. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damond, F., C. Apetrei, D. L. Robertson, S. Souquiere, A. Lepretre, S. Matheron, J. C. Plantier, F. Brun-Vezinet, and F. Simon. 2001. Variability of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) infecting patients living in France. Virology 280:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damond, F., M. Gueudin, S. Pueyo, I. Farfara, D. L. Robertson, D. Descamps, G. Chene, S. Matheron, P. Campa, F. Brun-Vezinet, and F. Simon. 2002. Plasma RNA viral load in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 subtype A and subtype B infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3654-3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Mendoza, C., M. Koppelman, B. Montes, V. Ferre, V. Soriano, H. Cuypers, M. Segondy, and T. Oosterlaken. 2005. Multicenter evaluation of the NucliSens EasyQ HIV-1 v1.1 assay for the quantitative detection of HIV-1 RNA in plasma. J. Virol. Methods 127:54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb, G. S., S. E. Hawes, H. D. Agne, J. E. Stern, C. W. Critchlow, N. B. Kiviat, and P. S. Sow. 2006. Lower levels of HIV RNA in semen in HIV-2 compared with HIV-1 infection: implications for differences in transmission. AIDS 20:895-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marlink, R., P. J. Kanki, I. Thior, K. Travers, G. Eisen, T. Siby, I. Traore, C. Hsieh, M. Dia, E. Gueye, J. Hellinger, A. Guèye-Ndiaye, J. Sankalé, I. Ndoye, S. Mboup, and M. E. Essex. 1994. Reduced rate of disease development after HIV-2 infection as compared to HIV-1. Science 265:1587-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullins, C., G. Eisen, S. Popper, A. Sarr, J. Sankalé, J. Berger, S. Wright, H. Chang, G. Coste, T. Cooley, P. Rice, P. Skolnik, M. Sullivan, and P. Kanki. 2004. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and viral response in HIV type 2 infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1771-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popper, S. J., A. D. Sarr, K. U. Travers, A. Gueye-Ndiaye, S. Mboup, M. E. Essex, and P. J. Kanki. 1999. Lower human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 viral load reflects the difference in pathogenicity of HIV-1 and HIV-2. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1116-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodes, B., J. Sheldon, C. Toro, V. Jimenez, M. A. Alvarez, and V. Soriano. 2006. Susceptibility to protease inhibitors in HIV-2 primary isolates from patients failing antiretroviral therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:709-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodes, B., C. Toro, V. Jimenez, and V. Soriano. 2005. Viral response to antiretroviral therapy in a patient coinfected with HIV type 1 and type 2. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:e19-e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruelle, J., B. K. Mukadi, M. Schutten, and P. Goubau. 2004. Quantitative real-time PCR on LightCycler for the detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2). J. Virol. Methods 117:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schim van der Loeff, M. F., A. Hansmann, A. A. Awasana, M. O. Ota, D. O'Donovan, R. Sarge-Njie, K. Ariyoshi, P. Milligan, and H. Whittle. 2003. Survival of HIV-1 and HIV-2 perinatally infected children in The Gambia. AIDS 17:2389-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano, V., P. Gomes, W. Heneine, A. Holguin, M. Doruana, R. Antunes, K. Mansinho, W. M. Switzer, C. Araujo, V. Shanmugam, H. Lourenco, J. Gonzalez-Lahoz, and F. Antunes. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) in Portugal: clinical spectrum, circulating subtypes, virus isolation, and plasma viral load. J. Med. Virol. 61:111-116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Beuningen, R., S. A. Marras, F. R. Kramer, T. Oosterlaken, J. Westeun, G. Borst, and P. A. van de Wiel. 2001. Development of a high throughput detection system for HIV-1 using real-time NASBA based on molecular beacons, p. 66-72. In R. Raghvachari and W. Tan (ed.), Genomics and proteomics technologies, proceedings of SPIE, vol. 4264. Society of Photot-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandamme, A., M. Witvrouw, C. Pannecouque, J. Balzarini, K. Van Laethem, J. Schmit, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clerq. 2000. Evaluating clinical isolates for their phenotypic and genotypic resistance against anti-HIV drugs, p. 231. In R. Schinazi (ed.), Antiviral methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]