Abstract

We compared the antimicrobial susceptibility testing results generated by disk diffusion and the VITEK 2 automated system with the results of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution (BMD) reference method for 61 isolates of unusual species of Enterobacteriaceae. The isolates represented 15 genera and 26 different species, including Buttiauxella, Cedecea, Kluyvera, Leminorella, and Yokenella. Antimicrobial agents included aminoglycosides, carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, penicillins, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. CLSI interpretative criteria for Enterobacteriaceae were used. Of the 12 drugs tested by BMD and disk diffusion, 10 showed >95% categorical agreement (CA). CA was lower for ampicillin (80.3%) and cefazolin (77.0%). There were 3 very major errors (all with cefazolin), 1 major error (also with cefazolin), and 26 minor errors. Of the 40 isolates (representing 12 species) that could be identified with the VITEK 2 database, 36 were identified correctly to species level, 1 was identified to genus level only, and 3 were reported as unidentified. VITEK 2 generated MIC results for 42 (68.8%) of 61 isolates, but categorical interpretations (susceptible, intermediate, and resistant) were provided for only 22. For the 17 drugs tested by both BMD and VITEK 2, essential agreement ranged from 80.9 to 100% and CA ranged from 68.2% (ampicillin) to 100%; thirteen drugs exhibited 100% CA. In summary, disk diffusion provides a reliable alternative to BMD for testing of unusual Enterobacteriaceae, some of which cannot be tested, or produce incorrect results, by automated methods.

Members of the family Enterobacteriaceae continue to play an important role as causes of health care-associated infections (4, 31). In the past 25 years, several new members of the family Enterobacteriaceae have been described; however, most of these new species are infrequent causes of human infections (7). Many of these organisms, including Rahnella aquatilis, Buttiauxella agrestis, and Budvicia aquatica, are found in water environments, while others, such as Moellerella wisconsensis, have been isolated primarily from wild animals (21). Both case reports and case series document these organisms as occasional human pathogens. For example, Sarria et al. describe 27 clinically significant Kluyvera spp. infections from their institution and note additional reports of infections in the literature, including five cases of bacteremia (22). Cases of bacteremia caused by Cedecea, Leminorella, and Yokenella species also have been reported (1, 3, 10, 20).

Automated bacterial identification systems, such as VITEK 2 (bioMérieux, Durham, NC), are commonly used in microbiology laboratories across the United States; however, these instruments are limited in the ability to identify and provide antimicrobial susceptibility profiles for the rare species of Enterobacteriaceae. Many of these newer genera are not in the VITEK 2 database. When automated systems are unable to provide data, susceptibility patterns are typically determined by alternative methods, such as disk diffusion testing. However, there are instances for other organisms (e.g., Acinetobacter spp.) when disk diffusion testing yields results that are discordant with results generated by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, formerly NCCLS) broth microdilution (BMD) reference method (30). Although there have been studies describing the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns for several of these unusual species, to our knowledge there has been no systematic comparison of the categorical interpretive results of BMD and disk diffusion to determine the concordance of the two methods. The goal of this study was to determine whether disk diffusion and VITEK 2 give accurate susceptibility test results for these unusual isolates compared with the CLSI BMD reference method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Sixty-one isolates representing 15 genera and 26 species of rare or unusual organisms in the family Enterobacteriaceae were available in the strain collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Table 1). Isolates had previously been characterized by 48 conventional biochemical tests using standard methods (6-8, 14). The bacterial isolates were subcultured from −70°C storage onto Trypticase soy agar plates containing 5% defibrinated sheep blood (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD) a minimum of two times prior to testing. Biochemical test samples were incubated at 35 ± 1°C. The quality control strains used for antimicrobial susceptibility testing included Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 35218, and the extended-spectrum β-lactamase control strain Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 (5).

TABLE 1.

Identification and susceptibility testing results for 61 isolates of Enterobacteriaceae tested by BMD and VITEK 2

| Reference identification | No. of isolates tested | Organism in VITEK 2 database | VITEK 2 identification | VITEK 2 MIC report generatedb | VITEK 2 susceptibility interpretation by AESc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budvicia aquatica | 1 | No | NAa | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella agrestis | 1 | Yes | Isolate reported as unidentified | Yes | No |

| Buttiauxella brennerae | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella ferragutiae | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella gavinae | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella izardii | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella noackie | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Buttiauxella warmboldiae | 1 | No | NA | No; organism misidentified as B. agrestis, which is not considered valid for susceptibility testing | NA |

| Cedecea davisae | 3 | Yes | 1 isolate reported as unidentified; 2 isolates reported as C. davisae | Yes | Yes |

| Cedecea lapagei | 1 | Yes | C. lapagei | Yes | Yes |

| Cedecea neteri | 1 | Yes | Isolate misidentified as C. davisae | Yes | Yes |

| Edwardsiella tarda | 5 | Yes | E. tarda | Yes | Yes |

| Ewingella americana | 5 | Yes | E. americana | Yes* | Yes* |

| Hafnia alvei | 5 | Yes | 1 isolate reported as unidentified; 4 isolates reported as H. alvei | Yes | Yes |

| Kluyvera ascorbata | 2 | Yes | K. ascorbata | Yes | Yes |

| Kluyvera cryocrescens | 3 | Yes | K. cryocrescens | Yes | Yes |

| Leminorella grimontii | 2 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Leminorella richardii | 2 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Leminorella sp. strain 3 | 1 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Moellerella wisconsensis | 5 | Yes | M. wisconsensis | No; organism not considered valid for susceptibility testing | No |

| Photobacterium damsela | 4 | Yes | P. damsela | No; organism not considered valid for susceptibility testing | No |

| Pragia fontium | 2 | No | NA | Yes | NA |

| Rahnella aquatilis | 5 | Yes | R. aquatilis | No; organism not considered valid for susceptibility testing | No |

| Tatumella ptyseos | 1 | No | NA | Insufficient growth for MIC† | NA |

| Xenorhabdus sp. | 1 | No | NA | Insufficient growth for MIC† | NA |

| Yokenella regensburgei | 5 | No | NA | Yes* | NA |

NA, not applicable.

*, one isolate did not show sufficient growth for MIC determination; †, tested on multiple occasions with the same result.

AES, Advanced Expert System; NA, not applicable.

Automated identification and susceptibility testing.

Each isolate was tested with the VITEK 2 system (version R04.02) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Both a gram-negative identification card (ID-GNB) and an antimicrobial susceptibility testing card (AST-GN07) were inoculated with a bacterial suspension prepared in 0.45% saline equal to the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard with the Densi-Chek 2 system (bioMérieux, Durham, NC). Discrepant bacterial identifications were resolved by retesting the isolates with the VITEK 2 and reference tube biochemical tests (6-8, 14). Categorical interpretations of antimicrobial susceptibility test results from VITEK 2 were based on the Advanced Expert System, when available.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Organisms were tested by the BMD reference method described in document M7-A6 with BMD plates prepared in-house at the CDC according to the CLSI procedure (18). Plates contained twofold dilutions of antimicrobial agents at the following concentration ranges: 0.5 to 64 μg/ml for ceftazidime (CAZ); 0.5/4 to 64/4 μg/ml for piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP); 1 to 64 μg/ml for amikacin (AMK), ampicillin (AMP), and cefotaxime (CTX); 0.5 to 32 μg/ml for cefazolin (CFZ), cefepime (FEP), and cefoxitin (FOX); 1 to 32 μg/ml for imipenem (IPM); 0.25 to 16 μg/ml for gentamicin (GEN); 0.12 to 8 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin (CIP); and 0.25 and 4.75 to 8 and 152 μg/ml for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT). Plates were inoculated with a bacterial suspension prepared in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and incubated at 35°C for 18 to 20 h. The MIC for each antimicrobial agent tested by BMD was the lowest concentration of the agent (in micrograms per milliliter) that inhibited visible growth. Concurrently, the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the isolates were determined by the CLSI disk diffusion method (19) with the same bacterial suspension as was used for the BMD testing. Disks contained the following amounts of antimicrobials: 100/10 μg (TZP); 30 μg (AMK, CFZ, FEP, CTX, FOX, CAZ); 10 μg (AMP, GEN, IPM); 5 μg (CIP); and 1.25/23.75 μg (SXT). Disks were placed on Mueller-Hinton agar (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 35°C for 18 to 20 h. Categorical interpretations (susceptible, intermediate, or resistant) for both MIC and disk diffusion tests were the CLSI interpretative criteria for Enterobacteriaceae (5). Six additional drugs were tested by BMD for comparisons with VITEK 2 susceptibility test results. MIC plates contained twofold dilutions of antimicrobial agents at the following concentration ranges: 0.5 to 32 μg/ml for ampicillin-sulbactam (2:1) (SAM); 1 to 64 μg/ml for ceftriaxone (CRO); 0.25 to 8 μg/ml for levofloxacin (LVX); 0.25 to 16 μg/ml for meropenem (MEM); 0.5 to 64 μg/ml for piperacillin (PIP); and 0.25 to 16 μg/ml for tobramycin (TOB). Testing for extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production was performed if BMD MIC results were ≥2 μg/ml for CAZ, CTX, or CRO, in accordance with CLSI recommendations (5).

RESULTS

Overall susceptibility test results.

Of the sixty-one bacterial isolates tested by BMD, all were susceptible to the aminoglycosides (AMK, GEN, and TOB), fluoroquinolones (CIP and LVX), carbapenems (IPM and MEM), FEP, and SXT. There was variable resistance to AMP, several cephalosporins, and the β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, SAM and TZP (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility patterns of 61 test isolates to β-lactam antimicrobial agents determined by BMD

| Organism | No. of isolates | No. of isolates-susceptibility toa:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | SAM | CFZ | FOX | CTX | CAZ | CRO | TZP | ||

| Budvicia aquatica | 1 | 1-R | 1-S | 1-R | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S |

| Buttiauxella spp. | 7 | 7-S | 7-S | 1-I, 6-S | 7-S | 7-S | 7-S | 7-S | 7-S |

| Cedecea spp. | 5 | 3-R, 1-I, 1-S | 3-R, 2-S | 5-R | 5-R | 1-I, 4-S | 5-S | 1-I, 4-S | 5-S |

| Edwardsiella tarda | 5 | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Ewingella americana | 5 | 5-S | 5-S | 2-R, 1-I, 2-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Hafnia alvei | 5 | 1-R, 3-I, 1-S | 1-R, 4-S | 4-R, 1-I | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Kluyvera spp. | 5 | 1-R, 2-I, 2-S | 5-S | 2-R, 1-I, 2-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Leminorella sp. | 5 | 5-R | 1-R, 2-I, 2-S | 5-R | 5-S | 1-I, 4-S | 2-R, 3-S | 1-I, 4-S | 1-R, 4-S |

| Moellerella wisconsensis | 5 | 3-R, 1-I, 1-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Photobacterium damsela | 4 | 2-R, 2-S | 4-S | 4-S | 4-S | 4-S | 4-S | 4-S | 4-S |

| Pragia fontium | 2 | 1-R, 1-I | 1-I, 1-S | 2-R | 2-S | 2-S | 2-S | 2-S | 2-S |

| Rahnella aquatilis | 5 | 3-R, 1-I, 1-S | 5-S | 4-R, 1-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

| Tatumella ptyseos | 1 | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S |

| Xenorhabdus sp. | 1 | 1-S | 1-I | 1-I | 1-I | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S | 1-S |

| Yokenella regensburgei | 5 | 2-I, 3-S | 5-S | 4-R, 1-I | 5-R | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S | 5-S |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Comparison of BMD and disk diffusion results.

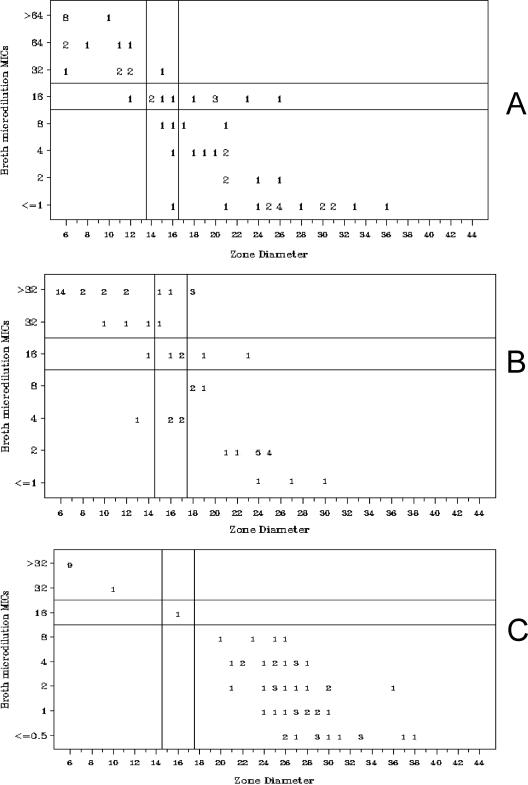

The susceptibility test results for the sixty-one isolates tested by disk diffusion are summarized in Table 3. Of the 12 antimicrobial agents tested by BMD and disk diffusion, 10 showed >95% categorical agreement (CA) (Table 3). CA was lower for AMP (80.3%) and CFZ (77.0%). All errors were minor (intermediate by one method and either susceptible or resistant by the other) except for CFZ, for which there were 3 very major errors, 1 major error, and 10 minor errors (Table 3). The scatterplots for AMP (Fig. 1A) and CFZ (Fig. 1B), for which errors were noted, are shown along with the scatterplot for FOX, for which no errors were noted (Fig. 1C). After repeat testing, 9 of the 26 minor errors resolved, as did 1 of the 3 very major errors.

TABLE 3.

Comparison between categorical interpretive results of BMD and disk diffusion testing

| Antimicrobial agent | CA (%)a | No. (%) of errorsb

|

No. of errors resolved upon repeat testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Major | Very major | |||

| AMK | 95.1 | 3 (4.9)* | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AMP | 80.3 | 12 (19.7)† | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| CFZ | 77.0 | 10 (16.4)‡ | 1 (3.8)‡ | 3 (10.3)‡ | 6 |

| FEP | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CTX | 98.4 | 1 (1.6)§ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FOX | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CAZ | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIP | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEN | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IPM | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TZP | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SXT | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Agreements of <90% are shown in boldface type.

Symbols: *, minor errors were observed with one L. grimontii and two P. damsela isolates; †, single minor errors were observed with C. davisae, C. neteri, M. wisconsensis, and K. ascorbata, two minor errors were observed with P. damsela, and three minor errors were observed for both H. alvei and K. cryocrescens; ‡, single minor errors were observed with R. aquatilis, H. alvei, L. richardii, and B. brennerae, two minor errors each were observed for P. damsela, K. ascorbata, and K. cryocrescens, and there was a single major error with P. damsela, two very major errors with Y. regensburgei, and one very major error with H. alvei; §, a single minor error was observed with L. richardii.

FIG. 1.

Scatterplots showing BMD MIC results (in micrograms per milliliter) versus disk diffusion zone diameters (in millimeters) for AMP (A), CFZ (B), and FOX (C) for 61 isolates. Four MIC datum points ≤ 1 for CFZ are not shown.

VITEK 2 identification results.

The data to identify 12 of the 26 species (represented by 40 isolates) tested were present in the VITEK 2 database (Table 1). Of these 40 isolates, 36 (90%) were identified correctly to species level, 1 was correctly identified to genus level only (one C. neteri isolate was identified as C. davisae), and 3 were unidentified.

Comparison of BMD and VITEK 2 susceptibility test results.

The VITEK 2 susceptibility test results fell into four categories based on whether the bacterial species was present in the VITEK 2 database and whether the identification was considered valid by VITEK 2 for susceptibility testing. For 22 of the 61 isolates, the bacterial identification by the instrument was considered valid for susceptibility testing, and MIC results and interpretations (susceptible, intermediate, or resistant) were reported (one E. americana isolate consistently showed insufficient growth for MIC testing). The organisms included four of five Cedecea spp. (the fifth was reported as unidentified), all five E. tarda isolates, four of five E. americana isolates, four of five H. alvei isolates (the fifth was reported as unidentified), and all five Kluyvera spp. The second group of 15 organisms was identified to species level by VITEK 2 but was not considered valid for susceptibility testing. Thus, no MIC data were reported. This group included one B. warmboldiae isolate that was identified as B. agrestis (which is not considered valid for susceptibility testing), all five M. wisconsensis isolates, all four P. damsela isolates, and all five R. aquatilis isolates. The third group of isolates consisted of those organisms for which no identifications were provided by VITEK 2, and yet MIC results were reported without interpretations. This occurred with 20 isolates, including six Buttiauxella spp., one of which (B. agrestis) was reported as unidentified; four Y. regensburgei isolates; one isolate each of C. davisae, H. alvei, and B. aquatica; all five Leminorella spp.; and both Pragia fontium isolates. Four isolates, including an E. americana, a T. ptyseos, a Xenorhabdus sp., and a Y. regensburgei, gave insufficient growth for susceptibility testing. Thus, VITEK 2 generated MIC results for 42 (68.8%) of 61 isolates; no susceptibility data were provided for the other 19 organisms. Categorical interpretations (susceptible, intermediate, or resistant) were provided for 22 (55.0%) of the 40 isolates in its database. For 21 (95.4%) of these 22 isolates, the categorical interpretations were provided via the VITEK 2 Advanced Expert System. The single isolate (C. neteri) that did not use Advanced Expert System rules for interpretation had been misidentified at the species level.

Most of the categorical errors for VITEK 2 were with AMP, SAM, and CFZ (Table 4). For the 17 antimicrobial agents tested by both BMD and VITEK 2, the essential agreement (EA) for the 42 isolates for which MIC results were generated by VITEK 2 ranged from 80.9 to 100% and CA (for 22 isolates) ranged from 68.2% (AMP) to 100%; 5 drugs exhibited 100% EA, and 13 drugs had 100% CA (Table 4). Discrepancies were most frequent for Leminorella sp. isolates (data not shown); excluding these from the analysis, the EA for three of the antimicrobial agents (FEP, CTX, and GEN) would have been 100% and that of CRO and CAZ would have increased to >95%. Of the isolates for which categorical interpretations were available, 10 (59%) of 17 errors were minor, 6 were major, and 1 was very major. Five of six major errors (one with AMP and four with SAM) occurred when the VITEK 2 Advanced Expert System rules changed the categorical interpretation to resistant even though the MIC generated was in the susceptible range. Similarly, one minor error occurred with Cedecea sp. due to erroneous changes made by the Advanced Expert System. The single C. neteri isolate for which Advanced Expert System rules were not applied had 100% CA for all 17 drugs tested.

TABLE 4.

EA and CA between results of BMD and VITEK 2

| Antimicrobial agent | % Agreementa

|

No. of errorsb

|

No. of errors resolved upon repeat testing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA (n = 42) | CA (n = 22) | Minor | Major | Very major | ||

| AMK | 90.5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP | 80.9 | 68.2 | 6* | 1* | 0 | 0 |

| SAM | 83.3 | 81.8 | 0 | 4† | 0 | 0 |

| CFZ | 85.7 | 77.3 | 3‡ | 1‡ | 1‡ | 0 |

| FEP | 88 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CTX | 90.5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CAZ | 90.5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CRO | 85.7 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CIP | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEN | 95.2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IPM | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| LVX | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MEM | NA | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PIP | 88 | 95.4 | 1§ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TZP | 85.7 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TOB | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SXT | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Agreements of <90% are shown in boldface type. NA, not applicable (VITEK 2 reported only categorical results for MEM; no MIC results were reported).

Symbols: *, there was a single minor error each observed with C. davisae and K. ascorbata, two minor errors with K. cryocrescens and H. alvei, and one major error with H. alvei; †, there was one major error with C. davisae and three major errors with H. alvei; ‡, there was a single minor error each observed with E. americana, H. alvei, and K. ascorbata, one major error with K. cryocrescens, and one very major error with K. cryocrescens; §, there was a single minor error with H. alvei.

Testing for ESBLs.

There were 10 isolates that met the CLSI screening criteria for ESBLs, based on a MIC result of ≥2 μg/ml for at least one extended-spectrum cephalosporin. These included two C. davisae, two R. aquatilis, two H. alvei, and four Leminorella sp isolates. Of these isolates, only one L. richardii isolate demonstrated a positive clavulanic acid effect, confirming the ESBL phenotype. For this isolate, the BMD MIC of CAZ dropped from >128 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml in the presence of clavulanic acid and the CTX MIC dropped from 16 μg/ml to ≤0.03 μg/ml in the presence of clavulanic acid. By disk diffusion testing, the CAZ zone diameter increased from 8 mm to 29 mm in the presence of clavulanic acid and the CTX zone diameter increased from 20 mm to 37 mm.

DISCUSSION

A key goal of this study was to assess whether the disk diffusion and VITEK 2 methods gave accurate susceptibility test results for a collection of unusual isolates of Enterobacteriaceae compared to the categorical interpretations generated by the BMD reference method. We also assessed the accuracy of the VITEK 2 identifications for the organisms that were listed in its database.

Previous studies have documented the susceptibility patterns of several of the unusual genera used in this study (23-29). There are also case reports describing the susceptibility patterns of clinical isolates of several of these species from human infections (9, 15, 32). In 1988, Freney et al. evaluated the susceptibility patterns of R. aquatilis, B. agrestis, E. americana, and K. ascorbata isolates to 13 antimicrobial agents by BMD (12).

In general, our MIC data are consistent with the MIC results reported in the literature for these organisms. However, our single isolate of B. agrestis was more susceptible to CFZ and FOX than were the isolates previously reported in the literature. Isolates from 10 other species tested showed resistance to AMP and CFZ suggestive of the chromosomal β-lactamases commonly encountered in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (16). However, none of the Rahnella, Hafnia, or Buttiauxella isolates tested were resistant to the extended-spectrum cephalosporins, which might have suggested a derepressed class C β-lactamase or an ESBL, both of which have been reported for these species (2, 11, 13). One L. richardii isolate, which was resistant to CAZ, showed a threefold decrease in BMD MICs for both CAZ and CTX when tested in the presence of clavulanic acid, confirming the presence of an ESBL. This isolate also demonstrated positive clavulanic acid tests for both CAZ and CTX by disk diffusion.

Our results confirmed the accuracy of disk diffusion for predicting the susceptibility of these unusual isolates of Enterobacteriaceae to a variety of antimicrobial agents. Only AMP and CFZ results were questionable. Fifty-eight percent (7 of 12) of the minor errors by AMP disk testing showed more susceptible results than BMD, with six of these errors potentially leading to the use of AMP to treat an organism classified as intermediate to this agent. Of similar concern, 36% of errors by CFZ disk testing (three very major errors and two minor errors) could result in inappropriate drug use for an intermediate or resistant organism. Even after repeat testing, the minor error rate for AMP and the very major error rate for CFZ exceeded the current acceptable error rates (10% and 1.5%, respectively) promulgated by CLSI guidelines (17). The majority of minor errors occurred with isolates of H. alvei, P. damsela, and Kluyvera species, and two of the three very major errors, which did not resolve with repeat testing, were with Y. regensburgei isolates. Thus, although in general the CLSI Enterobacteriaceae breakpoints can be used for interpreting the results of MIC and disk diffusion testing for unusual species of Enterobacteriaceae, caution may be needed when AMP and CFZ results are considered for certain species.

For species listed in the VITEK 2 database, the automated system correctly identified 90% of the organisms to species level; however, it provided a categorical interpretation of the susceptibility test results for only 22 organisms. Interestingly, application of VITEK 2 Advanced Expert System rules resulted in categorical errors even when there was essential agreement between the BMD and VITEK 2 MICs.

Most of the isolates tested grew well under standard testing conditions for BMD, disk diffusion, and VITEK 2 testing. Four isolates, including one C. davisae isolate, one H. alvei isolate, and both Leminorella grimontii isolates, required 24 h of incubation because of very light growth on disk diffusion testing. There were only four isolates that did not grow well enough in the VITEK 2 system to generate susceptibility profiles, despite repeat testing with a higher inoculum: one E. americana isolate, one Y. regensburgei isolate, and the single isolates of Xenorhabdus and Tatumella species.

The MIC results for the Leminorella isolates were often difficult to interpret due to trailing growth in the BMD plates. While growth equivalent to that in the positive control wells was noted in the susceptible MIC range, a filmy haze that coated the bottom of the wells was observed at higher drug concentrations. This haze, although distinctive from the negative control well, was difficult to interpret. Of note, the VITEK 2 system detected enough of a change in growth to report higher MIC results for these organisms than were obtained by BMD. These discrepancies between interpretations for Leminorella species accounted for almost 50% of the differences in EA between BMD and VITEK 2. It would be valuable to do further testing with a larger panel of Leminorella isolates to determine how frequently these species have trailing growth, but it would take clinical correlation to understand its significance.

A limitation to our study is the small numbers of each species tested. In most cases, the number tested reflected those isolates that were available in the CDC strain collection, limiting our ability to represent the entire spectrum of susceptibility for a given species. Most of the isolates were susceptible to all of the antimicrobial agents tested except for AMP, CFZ, and FOX. Thus, it is unknown how well the disk diffusion and VITEK 2 methods would agree with BMD results with more resistant strains. Nonetheless, disk diffusion, which is often the backup method for laboratories with automated systems, provided accurate susceptibility test results for these organisms. The VITEK 2 system identified 90% of the subset of isolates in its database correctly but provided MIC interpretations for only 55% of them. Thus, disk diffusion provides a reliable alternative to BMD for testing of unusual Enterobacteriaceae, some of which cannot be tested by automated methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cheryl Tarr and Nancye Strockbine for help in retrieving isolates from the CDC strain collection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, S. L., and J. M. Janda. 1994. Isolation of Yokenella regensburgei (“Koserella trabulsii”) from a patient with transient bacteremia and from a patient with a septic knee. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2854-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellais, S., L. Poirel, N. Fortineau, J. W. Decousser, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Biochemical-genetic characterization of the chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Rahnella aquatilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2965-2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blekher, L., Y. Siegman-Ingra, D. Schwartz, S. A. Berger, and Y. Carmeli. 2000. Clinical significance and antibiotic resistance patterns of Leminorella spp., an emerging nosocomial pathogen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3036-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chastre, J., and J. Y. Fagon. 2002. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165:867-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; fifteenth informational supplement. CLSI/NCCLS document M100-S15. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Edwards, P. R., and W. H. Ewing. 1972. Identification of Enterobacteriaceae, 3rd ed. Burgess Publishing Co., Minneapolis, MN.

- 7.Farmer, J. J., III. 2003. Enterobacteriaceae: introduction and identification, p. 636-653. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 8.Farmer, J. J., III, M. A. Asbury, F. W. Hickman, D. J. Brenner, and the Enterobacteriaceae Study Group. 1980. Enterobacter sakazakii: a new species of “Enterobacteriaceae” isolated from clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 30:569-584. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmer, J. J., III, J. H. Jorgensen, P. D. Grimont, R. J. Akhurst, G. O. Poinar, Jr., E. Ageron, G. V. Pierce, J. A. Smith, G. P. Carter, K. L. Wilson, and F. W. Hickman-Brenner. 1989. Xenorhabdus luminescens (DNA hybridization group 5) from human clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1594-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer, J. J., III, N. K. Sheth, J. A. Hudzinski, H. D. Rose, and M. F. Asbury. 1982. Bacteremia due to Cedecea neteri sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:775-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihman, V., M. Rottman, Y. Benzerara, F. Delisle, R. Labia, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2002. BUT-1: a new member in the chromosomal inducible class C β-lactamase family from a clinical isolate of Buttiauxella sp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 213:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freney, J., M. O. Husson, F. Gavini, S. Madier, A. Martra, D. Izard, H. Leclerc, and J. Fleurette. 1988. Susceptibilities to antibiotics and antiseptics of new species of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:873-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girlich, D., T. Nass, S. Bellais, L. Poirel, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Biochemical-genetic characterization and regulation of expression of an ACC-1-like chromosome-borne cephalosporinase from Hafnia alvei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1470-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickman, F. W., and J. J. Farmer III. 1978. Salmonella typhi: identification, antibiograms, serology, and bacteriophage typing. Am. J. Med. Technol. 44:1149-1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollis, D. G., F. W. Hickman, G. R. Fanning, J. J. Farmer III, R. E. Weaver, and D. J. Brenner. 1981. Tatumella ptyseos gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae found in clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 14:79-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livermore, D. M. 1995. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:557-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCCLS. 2001. Development of in vitro susceptibility testing and quality control parameters. Approved standard, 2nd ed. NCCLS document M23-A2. NCCLS, Wayne, PA.

- 18.NCCLS. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 6th ed. NCCLS document M7-A6. NCCLS, Wayne, PA.

- 19.NCCLS. 2003. Performance standard for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; approved standard, 8th ed. NCCLS document M2-A8. NCCLS, Wayne, PA.

- 20.Perkins, S. R., T. A. Beckett, and C. M. Bump. 1986. Cedecea davisae bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 24:675-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandfort, R. F., W. Murray, and J. M. Janda. 2002. Moellerella wisconsensis isolated from the oral cavity of a wild raccoon (Procyon lotor). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2:197-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarria, J. C., A. M. Vidal, and R. C. Kimbrough III. 2001. Infections caused by Kluyvera species in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:e69-e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stock, I. 2005. Natural antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Kluyvera ascorbata and Kluyvera cryocrescens strains and review of the clinical efficacy of antimicrobial agents used for the treatment of Kluyvera infections. J. Chemother. 17:143-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock, I., E. Falsen, and B. Wiedemann. 2003. Moellerella wisconsensis: identification, natural antibiotic susceptibility and its dependency on the medium applied. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock, I., T. Grüger, and B. Wiedemann. 2000. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Rahnella aquatilis and R. aquatilis-related strains. J. Chemother. 12:30-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stock, I., M. Rahman, K. J. Sherwood, and B. Wiedemann. 2005. Natural antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and biochemical identification of Escherichia albertii and Hafnia alvei strains. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51:151-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stock, I., K. J. Sherwood, and B. Wiedemann. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, β-lactamases, and biochemical identification of Yokenella regensburgei strains. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 48:5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stock, I., K. J. Sherwood, and B. Wiedemann. 2003. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Ewingella americana strains. J. Chemother. 15:428-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stock, I., and B. Wiedemann. 2001. Natural antibiotic susceptibilities of Edwardsiella tarda, E. ictaluri, and E. hoshinae. Antimicrob. Agents and Chemother. 45:2245-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swenson, J. M., G. E. Killgore, and F. C. Tenover. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Acinetobacter spp. by NCCLS broth microdilution and disk diffusion methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5102-5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco, E., R. Byington, C. S. Martins, M. Schirmer, L. C. Dias, and V. M. Goncalves. 2004. Bloodstream infection surveillance in a cancer centre: a prospective look at clinical microbiology aspects. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:542-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamane, K., J. Asato, N. Kawade, H. Takahashi, B. Kimura, and Y. Arakawa. 2004. Two cases of fatal necrotizing fasciitis caused by Photobacterium damsela in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1370-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]