Abstract

By use of a very sensitive nested PCR method targeting part of the strongly conserved mycoplasmal 16S RNA genes, Mycoplasma pneumoniae was found in the synovial fluid of 19/24 (79%) of rheumatoid arthritis patients, 6/6 (100%) of patients with nonrheumatoid inflammatory arthritis, and 8/10 (80%) of osteoarthritis patients attending the rheumatology clinic for drainage of joint effusions. It was not found in the synovial exudates of 13 people attending the orthopedic clinic with traumatic knee injuries or undergoing surgery for knee replacement. However, M. pneumoniae was detected in 2/4 synovial biopsy specimens from orthopedic patients with traumatic knee injuries. M. pneumoniae was associated with the increased synovial fluids found in arthritic flares but was not found in the synovial fluids of trauma patients. Mycoplasma salivarium occurred sporadically. Mycoplasma fermentans had previously been isolated from patients with inflammatory cellular infiltrates, such as rheumatoid arthritis, but it was not detected for osteoarthritic patients from either clinic. It is possible that these organisms may contribute to chronic inflammation within the joints.

Mycoplasmas have been isolated from the arthritic joints of many animals (16). In humans, Mycoplasma fermentans has been isolated from the joints of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and other seronegative patients with inflammatory arthritides and a cellular infiltrate (IA) and is discussed in our previous paper (9), although some data on this mycoplasma are included in this paper for comparison. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a human pathogen that is known to cause respiratory infections and sometimes pneumonia. Some patients (0.9%) with serologically verified M. pneumoniae infections developed arthritis (3, 7), and the four-yearly peaks in M. pneumoniae cases in Canada showed a significant epidemiological link with new cases of juvenile chronic arthritis (13). M. pneumoniae has also been isolated from the joints of other arthritic patients (19), particularly those with hypogammaglobulinemia (5, 10), and can clearly be arthritogenic in some cases.

Mycoplasma salivarium is not normally regarded as a pathogen, although there is one report of it causing arthritis in the joint of a patient with hypogammaglobulinemia (17). Otherwise, it is found in the gingival crevices and has been reported in synovial fluids from 24/33 patients with pain in or anterior disc displacement of the temporomandibular joint, although 19/33 patients also showed the presence of M. fermentans (20).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Synovial fluid samples were collected in the rheumatology clinic from the knees of 25 patients with RA, all of which fulfilled the American Rheumatism Association criteria for diagnosis (1). As a control for the RA patients, samples were collected from seven patients with other IA, namely, two with ankylosing spondylitis, one with pauciarticular juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA), one with reactive arthritis, two with gout, and one with psoriatic arthritis, as shown in Table 1. Samples were also collected from 10 patients with osteoarthritis (OA). Samples from both knees were obtained for five RA patients, one reactive arthritis patient, and one ankylosing spondylitis patient. Samples were obtained on two occasions, at least 3 months apart, from the same patient for three RA patients and the JCA patient. The samples were not all collected by the same clinician. No patients were being treated with antibiotics at the time of sample collection.

TABLE 1.

Patient details

| Disease group | No. of Patients | Mean age (yr) | F/M ratioc | Disease duration (yr) | Duration range (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | 25 | 59.7 | 1.5:1 | 10.2 | 1-39 |

| IAa | 7 | 41.4 | 0.4:1 | 5.2 | 0-23 |

| OA | 10 | 65.6 | 2.3:1 | 0.33-14 | 0.33-14 |

| Control, young traumatic | 4 | 26 | 0:4 | NA | NA |

| Traumatic OA | 9 | 56 | 1:2 | NA | NA |

| Traumaticb biopsy | 4 | 45.5 | 1:3 | NA | NA |

IA is inflammatory arthritis other than RA. Samples came from the rheumatology clinic, as did the RA and first 10 OA samples.

The biopsy samples were from three males, ages 29, 51, and 68, and one female, age 34. Only the youngest was free of arthritis; the older three showed signs of osteoarthritis.

F, female; M, male.

Synovial fluid samples were also obtained from the orthopedic clinic. Four were from young males aged 23 to 32 years (mean, 27.3 years) who had either an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament, a loose body in the knee joint, or damage to the meniscus and did not have arthritis. Members of the older group were of ages 52 to 72 years (mean, 61.6), six males and three females, all of whom showed radiological changes consistent with OA. One was undergoing chondroplasty, three had knee replacements, and the rest had damage to the meniscus. Details are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Orthopedic trauma patients

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Sexa | Knee problem | Mycoplasma (nb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 | M | Anterior cruciate ligament rupture | None (2) |

| 2 | 26 | M | Loose body, left knee | None (1) |

| 3 | 28 | M | Meniscal tear | None (2) |

| 4 | 32 | M | Menisectomy, some white cells | None (2) |

| 5 | 52 | M | Menisectomy, synovitis, few cells, OA | M. salivarium |

| 6 | 55 | M | Menisectomy, medial condyle, OA | M. salivarium |

| 7 | 55 | F | Menisectomy, synovitis, some white cells, OA | None (2) |

| 8 | 59 | M | Chondroplasty, no white cells, OA | None (2) |

| 9 | 61 | F | Meniscal tear, OA | M. salivarium |

| 10 | 68 | M | Mild OA | None (1) |

| 11 | 64 | M | Knee replacement, OA | None (1) |

| 12 | 68 | M | Knee replacement, OA | M.salivarium (2) |

| 13 | 72 | F | Knee replacement, OA | M. salivarium |

| 29 | M | Synovial biopsy | M. pneumoniae | |

| 34 | F | Early OA, synovial biopsy | None | |

| 51 | M | OA? Synovial biopsy | None | |

| 68 | M | Mild OA, synovial biopsy | M. pneumoniae |

F, female; M, male.

n, no. of samples.

The synovial fluid samples were obtained by sterile aspiration from the knees of patients attending the rheumatology clinic when aspiration was indicated as part of routine clinical practice. Consent for evaluation of the fluid was obtained. Only samples from patients with a clear and established diagnosis were included for the purposes of the study.

Control synovial fluids were obtained from patients attending the orthopedic clinic when undergoing knee repair or replacement. Four synovial biopsy specimens were also obtained.

Synovial fluid collection.

The samples were handled aseptically and were centrifuged at 500 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove the cells. Aliquots (usually 1 ml) were stored at −70°C.

Preparation of samples for PCR.

Samples were prepared in batches of 16 or 32 from mixed groups of patients and normally contained two blanks, which contained hyaluronidase and buffered saline. A 10-mg/ml solution of hyaluronidase in pyrogen-free water was freshly prepared and sterilized by filtration. The synovial fluids were thawed, and their viscosity was lowered by adding 20 μl/ml hyaluronidase solution and allowing them to stand for 0.5 h at room temperature. The samples were then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 0.5 h at 20°C, and the small pellet obtained was washed twice with sterile pyrogen-free saline, buffered at pH 8.0 with 10 mM Tris-HCl (TBS). Since the human cells had been removed before freezing, the procedure described above enriched any mycoplasmal DNA relative to the human DNA. For the blanks, hyaluronidase was added to 1 ml TBS, and the tubes were treated as were the other samples.

A fresh 10-mg/ml solution of proteinase K was prepared. The sample buffer contained 10 μl 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 12 μl proteinase K solution, and 0.978 ml pyrogen-free water. It was passed through a radiation-sterilized Amicon filter with a 50-KDa molecular cut-off to remove any DNA. Next, 50 μl of filter-sterilized 9% Tween 20 was added, and 0.1 ml of this mixture was added to the samples and blanks. These were heated at 37°C for 30 min and 60°C for 1 h, and then the proteinase K activity was destroyed by heating the samples at 96°C for 10 min. These samples were stored frozen at −20°C.

The biopsy specimens were dissolved in the proteinase K solution and then treated as were the other samples.

Primers.

The universal mycoplasma PCR primers were based on those described by Hopert et al. (6). The primers were obtained from Oswel DNA Service, University of Southampton, and were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography. They are shown in Table 3. The Cy5 sequencing primers were obtained from Pharmacia.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this worka

| Primer description | Name and 5′ sequence | Name and 3′ sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Outer | 9A, CGCCTGAGTAGTACGTTCGC | 3A, GCGGTGTGTACAAGACCCGA |

| Inner | 8A, *TGGTGCATGGTTGTCGTCAG | 5A, GAACGTATTCACCGCAGCATA |

| 7A, *GCATGGTTGTCGTCAGCTCG | 5B, GAACGTATTCACCGTAGCGTA | |

| 5F, GAACGTATTCACCGCGACATA | ||

| 5G, GAACGTATTCACCGCGACATG | ||

| Sequencing | SEQ1, Cy5-GACCCGAGAACGTATTCACC |

The asterisk shows that 8A and 7A were biotinylated at their 5′ end. The biotin interfered with the binding of primer 8A, but this problem was overcome using a hexaethylene glycol spacer. Primer 7A worked with or without the spacer. The sequencing primers were labeled with the fluorescent dye Cy5 and were designed to bind to the nonbiotinylated end of the PCR product. The sequences obtained were reversed and were complementary to the coding strand. The PCR amplification product from the outer primer pair was about 510 bp, and that from the inner pair was about 320 bp, depending on the organism.

PCR.

The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin (Perkin-Elmer Taq Gold buffer; diluted 10 times), 200 μM (each) of the nucleotides dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 200 nM of each primer, 0.2 U of Taq polymerase, and 5 μl sample. If a nested PCR was to be performed, the first round used Taq polymerase from Pharmacia or later TaKaRa Ex Taq, which contains a proofreading enzyme that increases the sensitivity of the reaction two- to threefold. In this case the buffer and deoxynucleoside triphosphate solutions supplied by the manufacturer were used. The mycoplasma was identified by sequencing the amplicon rather than by the use of species-specific primers, which are not as sensitive as nested PCRs. It was important to keep the pH at 8.3 for the biotinylated primer used in the second round, so either the Taq from Pharmacia or Taq Gold was used. The biotinylated primer *7A was used in preference to *8A, since the biotin itself interfered with the PCR unless it was attached to the primer by a spacer. Primers with a hexaethylene glycol spacer for 7A and 8A were very kindly supplied by Oswel and worked well. The PCR was carried out in 0.2-ml tubes, and the reaction mixture was overlaid with 30 μl sterile mineral oil. The thermal cycler was a Perkin-Elmer GeneAMP PCR system 9600.

The sample was initially dissociated by heating at 95°C for 3 min (Taq gold for 15 min) and then thermally cycled 50 times at 95°C for 35 s, 58°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 35 s, finally being left to extend at 72°C for 7 min before being cooled to 4°C. The relatively long annealing period was found to produce the best results. The blank samples from the first round were treated similarly. An 8-μl sample of the final reaction products was run on a 3% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg ml−1 ethidium bromide and photographed under a UV light. Those samples showing a clear PCR band were retained for sequencing. A photograph of the PCR bands obtained for M. fermentans is published in reference 9, and bands for M. pneumoniae and M. salivarium were identical, except that a different primer was used (see Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Human mycoplasmas and primers

| Mycoplasma (reference) | No. of inner bases | Primerc |

|---|---|---|

| M. fermentans (9) | 332a | 5B |

| M. salivarium (17) | 334b | 5F (5A) |

| M. hominis (11) | 332b | (5A) |

| M. orale (15) | 333a | (5B)* |

| M. lipophilum | 331 | (5B) |

| M. pneumoniae (10) | 317b | 5F |

| M. genitalium (18) | 317b | (5F) |

| M. pirum | 317 | (5F) |

| M. penetrans | 318 | (5G)* |

| Ureaplasma urealyticum (15) | 317b | (5G) |

Previously isolated from arthritis patients.

Previously isolated from arthritis patients, especially from patients with hypogammaglobulinemia or agammaglobulinemia.

The primer numbers that are not in parentheses were used to detect the mycoplasmas. Those in parentheses show the sequence that matches the 16S rRNA genes. Mycoplasmas would cross-hybridize if two base pairs mismatched, providing these were not within four bases of the 3′ end. The asterisk indicates a single mismatch, so the primer would detect the mycoplasma.

Sequencing.

An ALF express automated sequencer was used, with the solid-phase sequencing kit supplied by the manufacturer (Pharmacia). The biotinylated PCR product was removed from the reaction mix by allowing it to adhere to four streptavidin-coated plastic combs. The Cy5-labeled sequencing primer (obtained from Pharmacia) was first allowed to bind to the PCR product, and then the sequencing reaction was run using T7 polymerase and the deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixes provided by the manufacturer. The reaction products were dissociated from the combs using the iodoacetamide mixture provided and electrophoresed down a 6% polyacrylamide gel, using a 0.089 M Tris-borate buffer, pH 8.3, with 2 mM EDTA, obtained as a 10× concentrate from National Diagnostics. The dye-labeled products were visualized by a laser and the sequence shown on a computer. This sequence, when reversed and complemented, was compared to the prokaryotic DNA sequences on the PCGENE or EMBL database to identify the organism.

Precautions against contamination.

Since the mycoplasmal content of the synovial fluids was extremely small, it was both difficult to measure and easy to contaminate. It was essential to do the DNA extraction and PCR under sterile conditions, since the primers used could react to some extent with other bacteria and contaminate the PCR band, so making the mycoplasma 16S rRNA gene sequence unreadable or giving the bacterial sequence instead.

Pyrogen-free saline and water for injection were used in the isolation of the sample and the PCRs, since even commercially available molecular biology water, though sterile, was found to be contaminated by cross-hybridizing bacterial DNA, presumably from the ion-exchange columns used to purify it. The Eppendorf tubes and 0.2-ml PCR tubes were sterilized in an autoclave, and the other plastics and pipette filter tips were bought radiation sterilized. Even so, it was necessary to pass the PCR master mix, excluding the Taq and sample, through a 50-KDa radiation-sterilized Amicon filter to remove bacterial DNA if primer 5F or 5G was used. Given that the PCR bands were sequenced, there was no danger of a band due to a bacterial contaminant being identified as a mycoplasma. If the PCR band did not bind the sequencing primer, the PCR experiment was repeated and the band disappeared, showing that it was a contaminant. New Gilson pipettes and Finnpipettes were acquired and were used solely with the filter tips for PCR. Disposable plastic trays were used to prepare PCRs.

The batch preparation of mixed samples and blanks and the preparation of more than one sample from each individual in different batches were again precautions against contamination, although sometimes not enough material was available for more than one sample. The sequencing of the PCR band identified the organism.

RESULTS

Table 4 shows the breakdown of mycoplasma species detected in the disease groups. The presence of M. pneumoniae was almost universal in the patients from the rheumatology clinic but not in those from the orthopedic clinic. By contrast, M. fermentans was confined to cases of rheumatoid or other inflammatory arthritides and was not found in any of the 19 OA patients from either clinic. The data on M. fermentans have been reported previously (9) but are included for comparison. M. salivarium occurred less often in both inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritides from both clinics. However, it may have been overlooked in mixed infections with M. pneumoniae, since both mycoplasmas reacted with the same primers and were distinguished only by sequencing. The PCR would detect the most abundant organism. M. fermentans required different primers and so did not interfere with the detection.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of mycoplasma species among patient disease groups

| Patient group | No. of samples positive for mycoplasma/no. studied (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| M. fermentans | M. pneumoniae | M. salivarium | |

| RA | 23/25 (92) | 19/24 (79) | 1/24 (4) |

| OA | 0/10 (0) | 8/10 (80) | 2/10 (20) |

| IA | 6/7 (87) | 6/6 (100) | 0/6 (0) |

| Control, young traumatic | 0/4 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/4 (0) |

| Traumatic OA | 0/9 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 5/9 (56) |

| Traumatic biopsy | 0/4 (0) | 2/4 (50) | 0/4 (0) |

Synovial fluid from four young male orthopedic patients of ages between 23 and 32 (mean, 26) years showed no disease and no mycoplasma infection. The other nine orthopedic patients, ages 52 to 72 (mean, 62), all showed radiological changes consistent with at least mild OA, and 5/9 (56%) were infected with M. salivarium. No M. fermentans or M. pneumoniae was found in these samples. However, one synovial biopsy specimen from a 29-year-old male showed the presence of M. pneumoniae, as did a biopsy specimen from a 68-year-old male with OA. Two other biopsy specimens, from a female (age 34) and a male (age 68) showing signs of radiological changes of OA, were negative for all mycoplasmas.

Table 5 shows the primers used to detect the mycoplasmas and the sizes of the PCR products. In general, it was found that the mycoplasmal rRNA genes would be amplified if one of the primers had up to two mismatches, providing that no mismatch occurred within four base pairs of the 3′ end. The second primer matched exactly. Primer 9A matched the M. fermentans rRNA genes exactly but also amplified the rRNA genes from M. salivarium and M. pneumoniae, which both had a two-base mismatch. Other human mycoplasmas, and particularly those which have been isolated from joints but which were not found in this study, are also shown in Table 5.

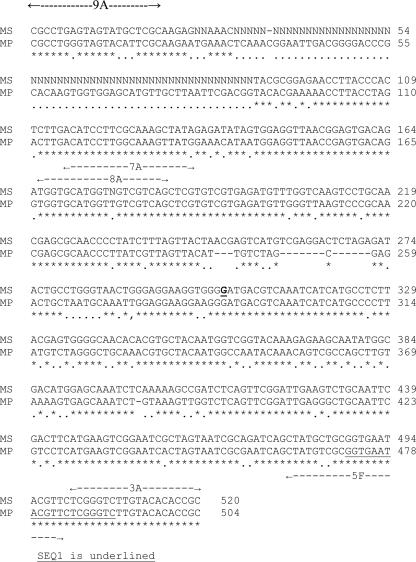

Figure 1 shows the coding strands of the 16S rRNA genes of the two mycoplasmas identified in this study. The positions of the outer and inner primers are marked, and the sequencing primers are indicated. It will be seen that the DNA is very strongly conserved. If the two DNA sequences shown here are compared with that for M. fermentans, 71.5% of the bases inside the inner primers are identical for all three organisms and 24% of the remaining bases show a partial identity. The data for M. fermentans are shown and discussed in reference 9. Mycoplasmal PCR bands were obtained from all the samples, except for the first sample from the JCA patient. A PCR band was obtained, but this failed to sequence, and a bacterial contaminant was suspected.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the part of the 16S rRNA genes for M. pneumoniae and M. salivarium used to identify the organisms in synovial fluid. MS is M. salivarium, edited part of sequence MSRRNAS. MP is M. pneumoniae, part of sequence MPRRNAPN. Positions of the outer and inner primers are marked with dotted lines and arrows, and sequencing primers are underlined. Base 304 is underlined and in bold type as it was identified by the sequencer. It is described as N in sequence MSRRNAS and is identical to the corresponding base in M. pneumoniae.

The sequence for M. pneumoniae was unambiguous and could readily be distinguished from that of the related Mycoplasma genitalium.

The sequence for M. salivarium was indistinguishable from those of three other animal mycoplasmas, Mycoplasma arginini (sheep and goats), Mycoplasma arthritidis (rodents), and Mycoplasma canadense (cattle). It was also close to but just distinguishable by one base from that of Mycoplasma orale.

DISCUSSION

M. pneumoniae infection occurs frequently in the general population. The sera of people over the age of 18 showed that at least 60% were positive for immunoglobulin G (IgG) against M. pneumoniae, although the actual proportion varied depending on the test used and somewhat declined in those over 65 (12). M. pneumoniae may be sequestered in the synovium of joints, causing no symptoms. It was detected in 2/4 synovial biopsy specimens from the orthopedic patients. An acute inflammatory synovitis with joint effusion may be associated with the migration of M. pneumoniae from the synovium to the synovial fluid in patients with RA, seronegative arthritides, or OA. This may be precipitated by a transient immune suppression. M. pneumoniae is known to induce autoantibodies against the surface antigens of lymphocytes (2), which may exacerbate the suppression.

The results support this hypothesis. M. pneumoniae was very common in the joints of all the arthritis patients attending the rheumatology clinic, whereas M. fermentans was restricted to those inflammatory arthritides with cellular infiltrates. However, neither mycoplasma was found in the synovial fluid of patients with traumatic knee injuries attending the orthopedic clinic, either in the knee joints of four young men or in the knee joints of older people who showed radiological changes of osteoarthritis and in some of whom the osteoarthritis was so severe as to require joint replacement. It seems, therefore, that M. pneumoniae may be associated with the synovial effluent found in the swollen knees of the RA, OA, and other patients attending the rheumatology clinic for whom trauma is not known to have been involved.

An inflammatory phase early in the development of osteoarthritis has been reported by several authors and is discussed by Dieppe (4). The cause of the inflammation is still speculative, but M. pneumoniae might possibly be involved. It would be difficult to detect by conventional means, since antibodies are likely to be present anyway (12) and it is extremely difficult to grow.

Although masking of M. pneumoniae or M. salivarium by each other might occur, the amount of DNA detected from both species was very low and there was no evidence that the two OA patients with M. salivarium in their synovial fluid also had M. pneumoniae, since there was no evidence of its 317-base peak on the polyacrylamide sequencing gel. Likewise, M. salivarium was not found in the joints of patients with M. pneumoniae, since the 334-bp peak was absent. No evidence for the presence of the other mycoplasmas reported to be isolated from arthritis patients was found.

Comparison with previous workers.

The prevalence of M. pneumoniae in the arthritic joints of patients with RA and OA has not previously been reported; however, it is in agreement with the frequent occurrence of IgG antibodies against M. pneumoniae in serum and their persistence into old age (12). IgG against M. pneumoniae has also been reported to be significantly more common in the sera of patients with RA as opposed to control sera, but the IgG levels in sera from OA and RA patients were not compared (14). The detection of M. salivarium for 20% of the OA patients was also quite unexpected, although the organism is very common in the oropharynx and is frequently found in inflamed tonsils. Unlike M. pneumoniae, it is not regarded as a pathogen, although both M. pneumoniae and M. salivarium are proven causes of arthritis in patients suffering from hypogammaglobulinemia (10, 17).

However, RA patients have significantly more mycoplasmal rRNA in their synovial fluid than patients with other arthritides (8), so they may have a particular difficulty dealing with these organisms. They may well contribute to the inflammation and chronicity of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Acton for providing the samples from the orthopedic patients, David Pitcher for providing the mycoplasmal DNAs with which to test the primers, and Angus Dalgleish for allowing us to use his automated sequencer.

The St. George's Hospital Special Trustees supported this work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnett, F. C., S. M. Edworthy, D. A. Bloch, D. J. McShane, J. F. Fries, N. S. Cooper, L. A. Healey, S. R. Kaplan, M. H. Liang, H. S. Luthra, T. A. Medsger, Jr., D. M. Mitchell, D. H. Neustadt, R. S. Pinals, J. G. Schaller, J. T. Sharp, R. L. Wilder, and G. G. Hunder. 1988. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 31:315-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biberfeld, G., P. Biberfeld, and H. Wigzell. 1976. Antibodies of surface antigens of lymphocytes and lymphoblastoid cells in cold-agglutinin-positive sera from patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 5:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, C. P., S. Cochran, J. Lisse, G. Buck, A. R. DiNuzzo, T. Weber, and J. A. Reinarz. 1988. Isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from synovial fluid samples in a patient with pneumonia and polyarthritis. Arch. Int. Med. 148:969-970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieppe, P. 1978. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Rehabil. 1978 (Suppl.):59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furr, P. M., D. Taylor-Robinson, and A. D. Webster. 1994. Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas in patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia and their role in arthritis: microbiological observations over 20 years. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 53:183-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopert, A., C. C. Uphoff, M. Wirth, H. Hauser, and H. G. Drexler. 1993. Specificity and sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in comparison with other methods for the detection of mycoplasma contamination in cell lines. J. Immunol. Methods 164:91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansson, E., A. Backman, K. Hakkarainen, A. Miettinen, and B. Seniusova. 1983. Mycoplasmas and arthritis. Zeitshr. Rheumatol. 42:315-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson, S. M., F. E. Bruckner, and D. A. Collins. 1996. Mycoplasmal RNA and 5′-nucleotidase in synovial fluid from arthritis patients. IOM letters, vol. 4. In Program Abstr. 11th Congr. Int. Organ. Mycoplasmol., p. 140. International Organization for Mycoplasmology, Ames, Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, S. M., D. Sidebottom, F. E. Bruckner, and D. A. Collins. 2000. Identification of Mycoplasma fermentans in synovial fluid samples from arthritis patients with inflammatory disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:90-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston, C. L., A. D. Webster, D. Taylor-Robinson, G. Rapaport, and G. R. Hughes. 1983. Primary late-onset hypogammaglobulinaemia associated with inflammatory arthritis and septic arthritis due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 42:108-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luttrell, L. M., S. S. Kanj, G. R. Corey, R. E. Lins, R. J. Spinner, W. J. Mallon, and D. J. Sexton. 1994. Mycoplasma hominis septic arthritis: two case reports and a review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:1067-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nir-Paz, R., A. Michael-Gayego, M. Ron, and C. Block. 2006. Evaluation of eight commercial tests for Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibodies in the absence of acute infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:685-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oen, K., M. Fast, and B. Postl. 1995. Epidemiology of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Manitoba, Canada, 1975-92: cycles in incidence. J. Rheumatol. 22:745-750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez, A. S., A. Rosas, J. A. Hernandez-Beriain, J. C. Orengo, P. Saavedra, C. de la Fe, A. Fernandez, and J. B. Poveda. 2005. Relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a case-control study. Rheumatology 44:912-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaeverbeke, T., H. Renaudin, M. Clerc, L. Lequen, J. P. Vernhes, B. De Barbeyrac, B. Bannwarth, C. Bebear, and J. Dehais. 1997. Systemic detection of mycoplasmas by culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedures in 209 synovial fluid samples. Br. J. Rheumatol. 36:310-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simecka, J. W., J. K. Davis, M. K. Davidson, S. E. Ross, C. T. Städtlander, and G. H. Cassell. 1992. Mycoplasma diseases of animals, p. 391-415. In J. Maniloff, R. N. McElhaney, L. R. Finch, and J. B. Baseman (ed.), Mycoplasmas, molecular biology and pathogenesis. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 17.So, A. K. L., P. M. Furr, D. Taylor-Robinson, and A. D. Webster. 1983. Arthritis caused by Mycoplasma salivarium in hypogammaglobulinaemia. Br. Med. J. 286:762-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor-Robinson, D., C. B. Gilroy, S. Horowitz, and J. Horowitz. 1994. Mycoplasma genitalium in the joints of two patients with arthritis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:1066-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tully, J. G., D. L. Rose, J. B. Baseman, S. F. Dallo, A. L. Lazzell, and C. P. Davis. 1995. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium mixture in synovial fluid isolate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1851-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe, T., K. Shibata, T. Yoshikawa, L. Dong, A. Hasebe, H. Domon, T. Kobayashi, and Y. Totsuka. 1998. Detection of Mycoplasma salivarium and Mycoplasma fermentans in synovial fluids of temporomandibular joints of patients with disorders in the joints. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 22:241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]