Abstract

Cryptosporidium spp. are a leading cause of diarrhea in Indian children, but there are no data for prevalent species or subgenotypes. Genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism and spatial analysis of cases using Geographical Information Systems technology was carried out for 53 children with cryptosporidial diarrhea in an urban slum. The two most common species were C. hominis (81%) and C. parvum (12%). Other species identified were C. felis and C. parvum (mouse genotype). Five subgenotypes were identified at the Cpgp40/15 locus. Subgenotype Ia predominated among C. hominis isolates, and all C. parvum isolates were subgenotype Ic. C. hominis infection was associated with a greater severity of diarrhea. Sequencing of the Cpgp40/15 alleles of C. felis and C. parvum (mouse genotype) revealed similarities to subgenotype IIa and C. meleagridis, respectively. Space-time analysis revealed two clusters of infection due to C. hominis Ia, with a peak in February 2005. This is the first study to demonstrate space-time clustering of a single subgenotype of C. hominis in a setting where cryptosporidiosis is endemic. Molecular characterization and spatial analysis have the potential to further the understanding of disease and transmission in the community.

Cryptosporidiosis is a major cause of diarrhea in children with and without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in developing countries (8, 16, 21, 27, 30). In these countries, cryptosporidial infection in early childhood has been reported to be associated with subsequent impairment in growth, physical fitness, and cognitive function (5, 20). In India, Cryptosporidium spp. are a leading cause of infectious diarrhea in children, with reported positivity rates ranging from 1.1% to 18.9% (11, 22, 24, 28).

The epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in humans is not completely understood due to the existence of multiple transmission routes such as person-to-person, animal-to-person, waterborne, food-borne, and possible airborne transmission (1). More recently, genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. at polymorphic loci has facilitated the development of molecular approaches with which to study the epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis (35, 36). Extensive polymorphisms in the Cpgp40/15 gene have been widely used to define at least eight allelic subgroups or subgenotypes of the parasite (14, 32). The majority of human infections, including those in developing countries, are caused by C. hominis (14, 17, 19, 29, 31, 33). There have been several studies of the prevalence rates of cryptosporidial infections in children in India, but there is only one report of the species or genotypes of Cryptosporidium spp. from children in eastern India (3), and none from southern India. Furthermore, there have been no studies of the genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium sp. infections in children in a well-defined community setting.

Geographical Information Systems (GIS) methods have previously been used to map the locations of residences of sporadic cases as well as in ecosystem studies of cryptosporidiosis (7, 10). The use of GIS to study the spatial distribution of cases has been found to be useful in identifying geographical variation but not necessarily for identifying the reasons for this variation. In this study, we determined the species, genotypes, and subgenotypes of Cryptosporidium sp. infections in a well-defined cohort of children in a semiurban community in Vellore, South India. A spatial analysis of children with cryptosporidial diarrhea was also carried out in order to study the transmission dynamics of cryptosporidiosis in this community.

(These data were presented, in part, at the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 54th Annual Conference, Washington, DC, December 2005.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population, sample collection, and screening.

The study subjects are part of an ongoing birth cohort of 452 children recruited for a study of rotaviral infections from a semiurban slum area with a population of approximately 33,390 in Vellore, in South India. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Christian Medical College, and informed consent was obtained from the parents. The children were enrolled at birth and followed for 3 years on a twice-weekly basis. Demographic and birth details were recorded at baseline. In this study, an episode was defined as at least 1 day of diarrhea (with the occurrence of three or more watery stools in a 24-h period) preceded and followed by 2 or more days without diarrhea. The episode was considered to have ended on the day bowel movements returned to normal (18). Children with diarrhea were assessed clinically, and details of the number of stools passed per day, any associated fever or vomiting, and treatment given were recorded daily until the cessation of diarrhea. These data were collected to calculate the Vesikari score, a scale used in rotaviral infection diarrhea to assess severity (23). Fecal samples collected from 1,949 of a total of 1,989 episodes of diarrhea over 14,584 child-months (the sum of months of follow-up of all children) of follow-up from April 2002 to January 2006 were screened for Cryptosporidium spp. by microscopic examination of modified acid-fast-stained smears, and these samples were also tested for other bacterial and parasitic diarrheal pathogens by culture and microscopy and for rotavirus by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Dako Cytomation rotavirus IDEIA, Ely, United Kingdom).

DNA isolation, identification of species, genotyping, and subgenotyping.

Briefly, DNA extracted from fecal samples positive for Cryptosporidium spp. by microscopy with a QIAamp stool DNA minikit (QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, CA) was subjected to PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) at the small-subunit (SSU) rRNA locus using enzymes SspI and VspI for species and genotype determination (34) and PCR-RFLP at the Cpgp40/15 locus using enzymes AluI and RsaI for subgenotyping (14) as previously described. Samples negative for SSU rRNA by PCR were analyzed by PCR-RFLP at the COWP and TRAP-C loci (25, 26). In samples where ambiguous results were obtained by PCR-RFLP at the Cpgp40/15 locus, the PCR products were purified using a QIAquick kit (QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, CA), sequenced by the dye terminator method, and compared with sequences of a known subgenotype using a ClustalW alignment algorithm of the AlignX program of Vector NTI, Suite 8 (Informax, North Bethesda, MD). The secondary PCR products of two C. felis samples, one obtained from an HIV-infected adult from a previous study (19) and one from a child in the present study, were cloned into a PCR 2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and the inserts were sequenced. The Cpgp40/15 PCR product of the C. parvum (mouse) was also sequenced and analyzed. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the maximum-likelihood method with BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor version 5.0.0 (6).

Spatial analysis.

The Poisson probability model (12) was used to identify any spatial or space-time clusters for high rates with the maximum spatial cluster size of 50% of the total population. Spatial analysis was carried out for cryptosporidial infections occurring from birth until January 2006 to detect any clustering of episodes by using SaTScan version 6.0 (13). The streets and the study houses of the urban slum area had been previously mapped and geographically referenced using ArcView GIS 3.3 (Environmental Systems Research, Inc., CA). The way points and track points were collected using a GPS Garmin V and downloaded as layers using GPS Utility 4.10.4. (GPS Utility Ltd., Southampton, England).

Statistical analyses.

Data generated during this study were double entered using Epi Info 6.4. software (CDC, Atlanta, GA) and analyzed using STATA version 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Statistical comparisons were made using Fisher's exact and chi-square tests.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences from this study were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers DQ 848995 to -97.

RESULTS

Cases.

Of the 1,949 diarrheal episodes screened, one or more diarrheal agents was detected in 591 episodes. Cryptosporidium spp. alone accounted for 7.61% of episodes and was the third most common etiologic agent after rotavirus and Giardia spp. Fifty-eight diarrheal episodes associated with Cryptosporidium spp. were identified in 53 children, with 5 children having two episodes each. Mixed infections from rotavirus, Shigella flexneri, Vibrio cholerae, or Giardia were identified in four children. In the children with repeated episodes of cryptosporidial diarrhea, the duration between the episodes ranged from 10 days to more than 1 year. Fifty-four of these episodes were treated with oral rehydration. None of the children with cryptosporidial diarrhea was hospitalized or required intravenous rehydration. In 7 of the 58 episodes, the child was found to be dehydrated clinically, based on assessments carried out in the field. A total of 5 of 452 children in the cohort died during the period of follow-up, with one death each due to congenital anomalies and a seizure disorder and three deaths due to diarrhea, but these diarrheal episodes were not associated with cryptosporidiosis.

Species and subgenotypes.

The species most commonly identified was C. hominis (47/58, 81%), followed by C. parvum in (7/58, 12.1%) and C. felis (3/58, 5.2%). One sample, which was negative by SSU (18S) rRNA PCR, was identified by COWP PCR. On comparison of the three PCR-based techniques with microscopy-positive samples, others have found a sensitivity of 97, 91, and 66% for the for the 18S rRNA, COWP, and TRAP-C1 gene fragments, respectively (15). Given this sensitivity, it is possible that 1 of 58 samples, tested twice, could be negative by SSU PCR but positive by COWP PCR. One sample with C. parvum (mouse genotype) was also identified (Fig. 1A). Subgenotyping of the 47 C. hominis-positive samples at the Cpgp40/15 locus showed that subgenotype Ia was the most common (35/47, 74.5%), followed by Id (8/47, 17%), Ie (3/47, 6.4%), and Ib (1/58, 1.7%). Subgenotyping of the C. parvum samples revealed that all seven were subgenotype Ic (Fig. 1B). In the five children with repeat infections, both infections were caused by C. hominis subgenotype Ia in four children and the remaining child had C. felis and C. hominis Ia infections.

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns are shown at the following locus for Cryptosporidium spp. after nested PCR amplification: SSU rRNA locus and digestion with SspI (lanes 1 to 4) and VspI (lanes 6 to 9). Lanes 1 and 6, C. hominis; lanes 2 and 7, C. parvum; lanes 3 and 8, C. parvum (mouse); lanes 4 and 9, C. felis; lane 10, 1-kb marker. (B) Cpgp40/15 locus and digestion with AluI: lane 1, C. hominis Ia; lane 2, C. parvum Ic; lane 3, C. hominis Id; lane 4, C. hominis Ib; lane 5, C. hominis Ie; lane 6, C. felis; lane 7, C. parvum (mouse); lane 8, 1-kb marker.

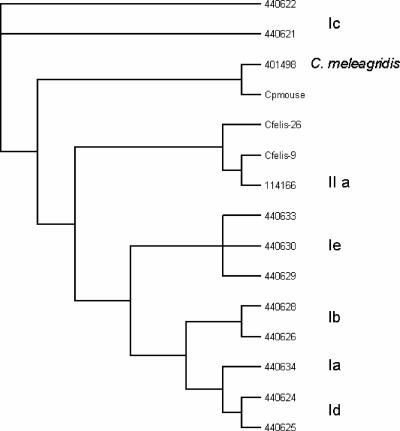

Cryptosporidium felis and C. parvum (mouse genotype) samples could not be classified into any previously described subgenotypes by PCR-RFLP at the Cpgp40/15 locus (Fig. 1B). Phylogenetic analysis of the Cpgp40/15 sequences revealed that the C. felis Cpgp40/15 allele was most closely related to the C. parvum IIa subgenotype (identities of 0.759/100% similarity over 795 bp) (Fig. 2), while the C. parvum (mouse genotype) allele was most closely related to the C. meleagridis allele (0.611/96% identity over 326 bp).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analyses of C. felis (sample 9 and 26) and C. parvum (mouse) Cpgp40/15 alleles using the maximum-likelihood method performed with BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor version 5.0.0. (Sequences from this study have been compared with the following sequences obtained from GenBank: AF440621-22, AF440624-26, AF440628-30, AF114166, AF440633-34, and AF 401498.)

Association of clinical characteristics with Cryptosporidium spp. and subgenotypes.

There were no significant differences in demographic (age, gender, birth order, educational status of the mother, or occupation of the father) or clinical (nutritional status assessed by weight and height for age, vomiting, fever, and hospital visits) characteristics between C. hominis-infected children and those infected with other species (Table 1) or between subgenotype Ia-infected children and those infected with other subtypes. However, C. hominis-infected children had a significantly greater severity of diarrhea (P, <0.05, Fisher's exact test). There was also a trend toward a longer average duration of diarrhea in C. hominis-infected children (P = 0.09) than in those infected with other species (Table 1). However, there was no increase in the severity of diarrheal symptoms in children who were coinfected with rotavirus, Shigella flexneri, Vibrio cholerae, and Giardia. Diarrhea associated with subgenotype Ia, the most commonly identified subgenotype, was not more severe than that associated with the other subgenotypes (P = 0.77). In the five children with repeated episodes of cryptosporidial diarrhea, the severity of diarrhea was increased in one case, decreased in two cases, and remained the same in the remaining two children during the second episode.

TABLE 1.

Association of demographic and clinical features with Cryptosporidium spp.

| Patient data | Incidence (%) of infection by

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. hominis (47 strains) | Other species (11 strains) | ||

| Demographic features | |||

| Age in mo at diarrhea onset (range)a | 14.4 (9.6-23.1) | 10.3 (7.3-24.4) | 0.17 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 22 (47) | 7 (64) | 0.50 |

| Female | 25 (53) | 4 (36) | |

| Birth order | |||

| First | 11 (23) | 2 (18) | 1.0 |

| Others | 36 (77) | 9 (82) | |

| Education of the mother | |||

| None | 12 (26) | 6 (55) | |

| Primary | 17 (31) | 4 (36) | 0.11 |

| More than primary | 18 (38) | 1 (9) | |

| Occupation of the father | |||

| Unskilled | 17 (36) | 5 (45) | 0.73 |

| Skilled | 30 (64) | 6 (55) | |

| Clinical features (no. [%] of patients) | |||

| Associated fever | 4 (9) | 2 (18) | 0.33 |

| Associated vomiting | |||

| No | 41 (87) | 9 (82) | 0.64 |

| Yes | 6 (13) | 2 (18) | |

| Malnutrition | |||

| Weightb | 14 (30) | 4 (36) | 0.72 |

| Heightc | 22 (47) | 3 (27) | 0.32 |

| % of patients with a diarrhea severity score ofd | |||

| 1-3 | 5 | 5 | |

| 4-5 | 12 | 4 | 0.005 |

| >6 | 29 | 2 | |

| No. of days of duration (range)e | 3 (2-5) | 2 (2-3) | 0.09 |

Median (25th to 75th percentile) no. of months, derived from Mann-Whitney test.

Weight for age <2 standard deviations.

Height for age <2 standard deviations.

Maximum no. of stools/day are given as percentages, derived by Fisher's exact test.

Median (25th to 75th percentile) no. of days, derived by the Mann-Whitney test.

GIS analysis.

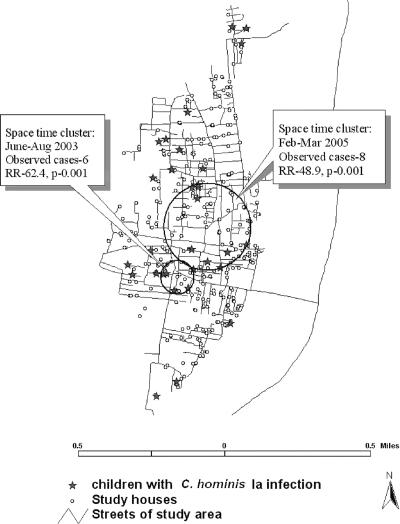

There were two significant space-time clusters of cryptosporidial diarrhea, one during February to March 2005 and the other during June to August 2003. The most likely space-time cluster involved six cases within a 0.07-km radius during the time frame of 1 February 2005 to 31 March 2005 (relative risk [RR], 133.8; P = 0.002). The second likely cluster involved eight cases during the time frame of 1 June 2003 to 31 August 2003 (RR, 22.9; P = 0.002). The calendar time distribution of cryptosporidial diarrhea during the follow-up period relative to the total diarrheal episodes experienced by the cohort also showed a peak in February 2005, with 16% of all diarrheal episodes in that month associated with Cryptosporidium spp. When children infected with C. hominis subgenotype Ia alone were analyzed, a similar pattern was found, in which the most likely space-time cluster involved eight cases that occurred within an area of 0.26 km radius during the same time period (RR, 48.9; P = 0.001), and the second most likely cluster involved six cases that occurred during 1 June 2003 to 31 August 2003 (RR, 62.4; P = 0.001) (Fig. 3). There was no clustering when the other subtypes were analyzed. Based on data collected during twice-weekly visits, we found that the cases belonged to different communities and that the children attended different schools, so we have no reason to suspect person-to-person transmission. No clustering was seen with the seven children with C. parvum infection. In order to identify potential zoonotic transmission of infection, the households and those of neighbors of the children with C. parvum and C. felis infections were questioned for the presence of cattle or domestic pets, but no history of exposure to these animals was found.

FIG. 3.

Spatial analysis with SaTScan version 6.0 of cases with C. hominis Ia infection, revealing two space-time clusters in the community.

The association between cryptosporidial diarrhea and the water source was also studied. In the community, five different overhead tanks supplied water to different areas. The tank-specific infection rates revealed that 7 of the 27 households which were supplied by a particular tank (tank 1) had cases of C. hominis Ia infection, which was a significantly higher rate than in areas supplied by the other tanks (chi-square test, P = 0.001). There was also a tank (tank 2) that was associated with only one episode of cryptosporidial diarrhea. Water samples from the area were tested for coliforms, and the most probable number/ml (MPN) was assessed. Of the three samples collected from the Kaspa region during January to March 2005, two had an MPN of >360, indicating a very high level of contamination that suggested a possible water-related transmission for this cluster. The technology and reagents for testing water samples for cryptosporidial oocysts are not readily available in India, and this test was not carried out.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to genetically characterize Cryptosporidium spp. identified in children in a community setting in India and to compare the association of species and subgenotype with clinical features, and it is also the first study to carry out spatial and temporal analyses of cryptosporidial diarrhea in India.

Compared to our previous, hospital-based study of Cryptosporidium spp. from HIV-infected adults in the same area (19), there were significant differences between the proportions of potentially zoonotic species in the two populations (chi-square test, P < 0.001), with fewer zoonotic species found in children in the community than in HIV-infected adults in the hospital. The Cpgp40/15 subgenotypes were also more diverse among the HIV-infected adults than among the children. The predominant subgenotypes among the C. hominis samples were Ib and If in HIV-infected adults, whereas Ia predominated in children. All C. parvum samples from children were Ic at the Cpgp40/15 locus, whereas several different subgenotypes, including IIa, IIb, and Ic, were seen in C. parvum samples from HIV-infected adults. These data suggest differences in transmission patterns or susceptibility to disease in these two populations, which merits further study of potential sources of infection in a developing country. In a previous report, a probability proportional to size cluster survey of approximately 3,000 samples from individuals in the 15- to 40-year-old age group was carried out to estimate the community prevalence of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus in rural and urban Vellore. This study showed that the prevalence of antibodies to HIV in the population was 0.66% (9). The program to prevent HIV transmission from parents to children has been in place since 2000, with all HIV-infected pregnant women throughout the state receiving antiretroviral therapy (http://www.unicef.org/india/hiv_aids_278.htm). Even in the absence of such a program, expected rates in children, who could possibly have had vertical transmission of infection, would be less than one-third of that in the adult population, or 0.22% in children or 1 child in the cohort of 452 recruited. Therefore, we do not believe that immunosuppression due to HIV could have been a significant risk factor for cryptosporidiosis in the 53 infected children or for recurrent diarrhea in the cohort.

Data for subgenotype distribution are scarce and are derived mainly from hospital-based studies and from outbreaks (2-4, 19); this is the first community-based study to subgenotype cryptosporidial samples in a developing country. This is also the first nonoutbreak study to show the predominance of one subgenotype, Ia, in the community. A previous study from Malawi involving community-acquired diarrhea in children showed the presence of six different subtypes among C. hominis samples (21). In the present study, diarrhea due to C. hominis infection was also found to be more severe than diarrhea due to other species in this community. A study from Peru reported longer periods of oocyst shedding in C. hominis-infected patients (33), but there has been no previous report of association with the severity of diarrhea.

The C. parvum samples were all subgenotype Ic, a subgenotype associated with anthroponotic transmission (35). In children infected with this species, no potential sources of zoonotic transmission were found. The finding that all C. parvum samples subgenotyped as Ic at the Cpgp40/15 locus, suggesting discordant alleles at the SSU rRNA locus, has been reported previously (14, 19, 21); and it has been suggested that this allele should be renamed IIc. These data collectively suggest a predominantly anthroponotic transmission cycle of Cryptosporidium spp. in this community, although the sources of infection were not conclusively determined.

The application of spatial and temporal analyses revealed two significant clusters of infections due to subgenotype Ia in children, which had not been identified with routine surveillance. Previous studies involving GIS and Cryptosporidium spp. have focused on the epidemiology of sporadic cases of cryptosporidiosis in the northwest of England and Wales (7) and have demonstrated contamination sites in watershed environments in Kenya and Ecuador (10). The present study is the first to apply GIS technology to document the epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in a well-defined community where the disease is endemic. Additionally, an area of the community supplied with water from a particular overhead tank (tank 1) was found to have a significantly higher incidence of cryptosporidiosis. In the area where one cluster of cases was identified by GIS technology, very high levels of fecal contamination of water samples were detected at the same time point and suggest the possibility of waterborne transmission. However, a conclusive demonstration of this requires the identification of oocysts of the same subgenotype in the source water. Previous studies of waterborne outbreaks have found an association with C. hominis subgenotype Ib (2, 4, 37). In contrast, the subgenotype seen in the children who potentially acquired cryptosporidiosis from tank 1 was Ia. Only 1 of the 47 C. hominis samples subgenotyped in this study was Ib, suggesting that waterborne transmission of subgenotype Ib may not be a significant mode of acquisition of disease in this area and that there may be a geographic variation in genotypes associated with waterborne transmission. Alternatively, it is possible that subgenotype Ib is less prevalent in India than in other transmission sites due to other as-yet-undefined reasons.

These data provide new evidence to support the need for the use of molecular and geospatial tools to investigate potential sources of infection and to study transmission patterns in the community in order to apply relevant interventional measures for the prevention of disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Fogarty International Research Cooperative Agreement and by grant 5R03TW2711 from the National Institutes of Health. The sample and data collection were supported by the Wellcome Trust Trilateral Initiative on Infectious Disease, grant no. 063144.

None of the authors has any financial interest in any commercial company represented in this study, nor any other potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caccio, S. M. 2005. Molecular epidemiology of human cryptosporidiosis. Parassitologia 47:185-192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen, S., F. Dalle, A. Gallay, M. Di Palma, A. Bonnin, and H. D. Ward. 2006. Identification of Cpgp40/15 type Ib as the predominant allele in isolates of Cryptosporidium spp. from a waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis in South Burgundy, France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:589-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das, P., S. S. Roy, K. MitraDhar, P. Dutta, M. K. Bhattacharya, A. Sen, S. Ganguly, S. K. Bhattacharya, A. A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2006. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in children in Kolkata, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4246-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaberman, S., J. E. Moore, C. J. Lowery, R. M. Chalmers, I. Sulaiman, K. Elwin, P. J. Rooney, B. C. Millar, J. S. Dooley, A. A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2002. Three drinking-water-associated cryptosporidiosis outbreaks, Northern Ireland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:631-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerrant, D. I., S. R. Moore, A. A. Lima, P. D. Patrick, J. B. Schorling, and R. L. Guerrant. 1999. Association of early childhood diarrhea and cryptosporidiosis with impaired physical fitness and cognitive function four-seven years later in a poor urban community in northeast Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61:707-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes, S., Q. Syed, S. Woodhouse, I. Lake, K. Osborn, R. M. Chalmers, and P. R. Hunter. 2004. Using a geographical information system to investigate the relationship between reported cryptosporidiosis and water supply. Int. J. Health Geogr. 3:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javier Enriquez, F., C. R. Avila, J. Ignacio Santos, J. Tanaka-Kido, O. Vallejo, and C. R. Sterling. 1997. Cryptosporidium infections in Mexican children: clinical, nutritional, enteropathogenic, and diagnostic evaluations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang, G., R. Samuel, T. S. Vijayakumar, S. Selvi, G. Sridharan, D. Brown, and C. Wanke. 2005. 2005. Community prevalence of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus in rural and urban Vellore, Tamil nadu. Natl. Med. J. India 18:15-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato, S., L. Ascolillo, J. Egas, L. Elson, K. Gostyla, L. Naples, J. Else, F. Sempertegui, E. Naumova, A. Egorov, F. Ojeda, and J. Griffiths. 2003. Waterborne Cryptosporidium oocyst identification and genotyping: use of GIS for ecosystem studies in Kenya and Ecuador. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50(Suppl.):S548-S549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaur, R., D. Rawat, M. Kakkar, B. Uppal, and V. K. Sharma. 2002. Intestinal parasites in children with diarrhea in Delhi, India. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 33:725-729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulldorff, M. 1997. A spatial scan statistic. Commun. Statist. Theory Meth. 26:1481-1496. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulldorff, M., G. Williams, and D. DeFrancesco. 1998. Software for the spatial and space-time scan statistics. SaTScan. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

- 14.Leav, B. A., M. R. Mackay, A. Anyanwu, R. M. O'Connor, A. M. Cevallos, G. Kindra, N. C. Rollins, M. L. Bennish, R. G. Nelson, and H. D. Ward. 2002. Analysis of sequence diversity at the highly polymorphic Cpgp40/15 locus among Cryptosporidium isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in South Africa. Infect. Immun. 70:3881-3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLauchlin, J., S. Pedraza-Diaz, C. Amar-Hoetzeneder, and G. L. Nichols. 1999. Genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium strains from 218 patients with diarrhea diagnosed as having sporadic cryptosporidiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3153-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molbak, K., N. Hojlyng, A. Gottschau, J. C. Sa, L. Ingholt, A. P. da Silva, and P. Aaby. 1993. Cryptosporidiosis in infancy and childhood mortality in Guinea Bissau, west Africa. BMJ 307:417-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan, U., R. Weber, L. Xiao, I. Sulaiman, R. C. Thompson, W. Ndiritu, A. Lal, A. Moore, and P. Deplazes. 2000. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates obtained from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals living in Switzerland, Kenya, and the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1180-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris, S. S., S. N. Cousens, C. F. Lanata, and B. R. Kirkwood. 1994. Diarrhoea—defining the episode. Int. J. Epidemiol. 23:617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muthusamy, D., S. S. Rao, S. Ramani, B. Monica, I. Banerjee, O. C. Abraham, D. C. Mathai, B. Primrose, J. Muliyil, C. A. Wanke, H. D. Ward, and G. Kang. 2006. Multilocus genotyping of Cryptosporidium sp. isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals in South India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:632-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niehaus, M. D., S. R. Moore, P. D. Patrick, L. L. Derr, B. Lorntz, A. A. Lima, and R. L. Guerrant. 2002. Early childhood diarrhea is associated with diminished cognitive function 4 to 7 years later in children in a northeast Brazilian shantytown. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:590-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng, M. M., S. R. Meshnick, N. A. Cunliffe, B. D. Thindwa, C. A. Hart, R. L. Broadhead, and L. Xiao. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in children in Malawi. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50(Suppl.):S557-S559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinthaler, F. F., F. Mascher, W. Sixl, U. Enayat, and E. Marth. 1989. Cryptosporidiosis in children in Idukki District in southern India. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 7:89-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruuska, T., and T. Vesikari. 1990. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 22:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sethi, S., R. Sehgal, N. Malla, and R. C. Mahajan. 1999. Cryptosporidiosis in a tertiary care hospital. Natl. Med. J. India. 12:207-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spano, F., L. Putignani, S. Guida, and A. Crisanti. 1998. Cryptosporidium parvum: PCR-RFLP analysis of the TRAP-C1 (thrombospondin-related adhesive protein of Cryptosporidium-1) gene discriminates between two alleles differentially associated with parasite isolates of animal and human origin. Exp. Parasitol. 90:195-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spano, F., L. Putignani, J. McLauchlin, D. P. Casemore, and A. Crisanti. 1997. PCR-RFLP analysis of the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene discriminates between C. wrairi and C. parvum, and between C. parvum isolates of human and animal origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinberg, E. B., C. E. Mendoza, R. Glass, B. Arana, M. B. Lopez, M. Mejia, B. D. Gold, J. W. Priest, W. Bibb, S. S. Monroe, C. Bern, B. P. Bell, R. M. Hoekstra, R. Klein, E. D. Mintz, and S. Luby. 2004. Prevalence of infection with waterborne pathogens: a seroepidemiologic study in children 6-36 months old in San Juan Sacatepequez, Guatemala. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:83-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanyam, V. R., R. L. Broadhead, B. B. Pal, J. B. Pati, and G. Mohanty. 1989. Cryptosporidiosis in children of eastern India. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 9:122-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiangtip, R., and S. Jongwutiwes. 2002. Molecular analysis of Cryptosporidium species isolated from HIV-infected patients in Thailand. Trop. Med. Int. Health 7:357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumwine, J. K., A. Kekitiinwa, S. Bakeera-Kitaka, G. Ndeezi, R. Downing, X. Feng, D. E. Akiyoshi, and S. Tzipori. 2005. Cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis in Ugandan children with persistent diarrhea with and without concurrent infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 73:921-925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tumwine, J. K., A. Kekitiinwa, N. Nabukeera, D. E. Akiyoshi, S. M. Rich, G. Widmer, X. Feng, and S. Tzipori. 2003. Cryptosporidium parvum in children with diarrhea in Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 68:710-715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, Z., I. Nagano, T. Boonmars, T. Nakada, and Y. Takahashi. 2003. Intraspecies polymorphism of Cryptosporidium parvum revealed by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and RFLP-single-strand conformational polymorphism analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4720-4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao, L., C. Bern, J. Limor, I. Sulaiman, J. Roberts, W. Checkley, L. Cabrera, R. H. Gilman, and A. A. Lal. 2001. Identification of 5 types of Cryptosporidium parasites in children in Lima, Peru. J. Infect. Dis. 183:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao, L., L. Escalante, C. Yang, I. Sulaiman, A. A. Escalante, R. J. Montali, R. Fayer, and A. A. Lal. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1578-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao, L., R. Fayer, U. Ryan, and S. J. Upton. 2004. Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:72-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao, L., and U. M. Ryan. 2004. Cryptosporidiosis: an update in molecular epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 17:483-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, L., A. Singh, J. Jiang, and L. Xiao. 2003. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp. in raw wastewater in Milwaukee: implications for understanding outbreak occurrence and transmission dynamics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5254-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]