Abstract

During the period from January to July 2004, a total of 131 influenza C viruses were detected by cell culture or reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) from specimens that were obtained from children with acute respiratory symptoms in 10 prefectures across Japan. Influenza C virus was identified most frequently in the Miyagi (1.4%, 45 of 3,226 specimens) and Yamagata (2.5%, 31 of 1,263 specimens) prefectures, and the frequency in this year was the highest since 1990. Phylogenetic analysis of the hemagglutinin esterase gene of the 13 strains isolated in nine prefectures revealed that genetically similar strains belonging to the Kanagawa/1/76-related lineage dominantly spread throughout Japan. During the 2004 influenza season, influenza C virus coexisted with epidemics of influenza A virus (H3 strain), and 12 cases were identified from patients who had been diagnosed with influenza-like illness (7 were detected by RT-PCR, and 5 were detected by culture). A comparison of specimens that were found positive by culture with those found positive only by RT-PCR shows that the amount of virus in PCR-positive specimens tended to be lower than in isolation-positive specimens. Although the mean peak temperature in patients in the PCR-positive group was slightly lower, there were no significant differences in characteristics between specimens (i.e., kind of specimen, period from onset to specimen collection, age distribution of patients, and severity of illness). These results suggest that an epidemic of influenza C virus occurred on a national scale during this period and that RT-PCR can be an effective supplemental tool for the evaluation of clinical and epidemiological information.

Influenza C virus usually causes a febrile upper respiratory tract illness (6, 17), and the majority of humans acquire antibodies to the virus early in life (5, 19). We recently described the clinical features of 170 children infected with influenza C virus and found that this virus is a significant cause of respiratory infections in children younger than 6 years of age and that the risk of complications with lower-respiratory-tract illness is high in children younger than 2 years of age (16). Furthermore, during our long-term surveillance of influenza C virus, which dates from 1988 in Yamagata Prefecture and from 1990 in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, most influenza C viruses were isolated during the period from January to June (16) and were prevalent in local communities at intervals of almost 2 years (12, 13). In winter months, it is difficult to differentiate clinically the influenza C virus infection from influenza viruses A and B, since most children infected with influenza C virus had fever (temperature of >38°C), and 20 (11.8%) of the 170 children were actually diagnosed with “influenza” (16).

Moreover, we have identified some important epidemiological features of influenza C virus: antigenically and genetically different strains cocirculate in a community (10), genetic reassorting occurs frequently among strains (13), and newly emergent reassortant viruses become predominant and may be prevalent throughout Japan (13, 14). However, there were only a small number of influenza C viruses isolated outside of the Yamagata and Miyagi prefectures (21, 22), since the isolation of this virus is difficult due to a lack of suitable cell line for isolation of influenza C virus. Thus, the overall epidemiological features of influenza C at a country level are yet to be sufficiently clarified.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) is a rapid, sensitive, and conventional diagnostic method; there are few differences in the performance of this technique among institutes; and RT-PCR is applicable even for the detection of inactivated viruses in specimens left in a freezer for a long time. There have been some reports on the use of the RT-PCR method to detect the influenza C virus (3, 4, 24), but there have been few reports on its actual use in the surveillance of this virus. In 2004, more than 70 strains of influenza C virus were isolated in Yamagata and Miyagi Prefectures, and we wanted to learn whether an epidemic of influenza C had occurred on a national scale. Using RT-PCR, we attempted a nationwide and retrospective study of clinical specimens that were found to be negative for common respiratory viruses by cell culture and were kept in freezers by the laboratories in several prefectures across Japan. We describe here our detection of influenza C viruses from 131 specimens by culture or RT-PCR in 2004 and, furthermore, show that RT-PCR is a useful tool for the epidemiology of influenza C as well as its virological diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

Between January and July 2004, throat swab or nasal aspirate specimens were collected from children who visited clinics with acute respiratory symptoms in 11 prefectures across Japan. The specimen was suspended in 3 ml of transport medium consisting of Eagle minimum essential medium with 0.5% gelatin, 200 U of penicillin and 200 μg of streptomycin per ml and then transported at 4°C to each laboratory for virus isolation. Specimens collected in Yamagata, Fukushima, Saitama, Aichi, Okayama, and Hiroshima prefectures and Fukuoka City (located in Fukuoka Prefecture) were transported to each municipal institute of public health, and those collected in the Miyagi, Niigata, Kanagawa, Osaka, and Fukuoka prefectures were transported to the Virus Research Center of Sendai Medical Center. For RT-PCR analysis, we used the clinical specimens that were found to be negative for common respiratory viruses by cell culture in Yamagata, Niigata, Aichi, Okayama, Hiroshima, and Fukuoka prefectures. The RT-PCR assay was performed in each institute of public health with the exception that this assay for specimens of Niigata and Okayama prefectures was done at Niigata University and Yamagata University, respectively.

Virus isolation.

Virus isolation was performed according to the microplate method described by Numazaki et al. (20). The specimen was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min, and 75 μl of supernatant was inoculated on the following cell lines in each well of a 96-well plate: human embryonic fibroblast, HEp-2, Vero, and MDCK. The inoculated plate was centrifuged for 20 min at 2,000 rpm and then incubated at 33°C in a CO2 incubator for 10 days. In order to allow influenza C virus multi-stepwise replication in MDCK cells, the maintenance medium of MDCK cells was supplemented with 3.5 μg of trypsin/ml. When a cytopathic effect was observed in MDCK cells, culture media were collected and tested for the presence of hemagglutinating agents by mixing the medium with an equal volume of chicken or guinea pig erythrocytes; influenza C virus agglutinates the former but not the latter. Finally, the isolates were identified by a hemagglutinin inhibition (HI) test with the anti-C/AnnArbor/1/50 serum as described previously (13).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR assay.

Viral RNAs were extracted from 100 μl of clinical specimens according to manufacturer's protocols by the use of one of the following commercial kits: RNeasy minikit, QIAamp viral RNA minikit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), TRIzol (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and Isogen-LS (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). RT was carried out at 42°C for 60 min in 20 μl containing 10 μl of RNA, 2 μl of 10× reaction buffer, 500 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 40 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI), 1 μg of random hexamer Pd(N)6 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and 7 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase XL (Life Science, St. Petersburg, FL), followed by incubation at 95°C for 5 min.

PCR was performed to amplify nonstructural protein (NS) gene as follows. First, 5 μl of cDNA was added to 45 μl of PCR mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 25 pmol of plus-sense primer (5′-dAAAATGTCCGACAAAACAGT; NS+24; sequence corresponding to positions 25 to 44), 25 pmol of minus-sense primer (5′-dCTAAGCGAGAGCATATAAGC; NS−751; positions 752 to 733), and 1.5 U of Ex Taq polymerase (Takara Biomedicals, Ohtsu, Japan). The PCR mixture was incubated for 1 cycle at 94°C for 1 min and then for 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 49°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension was run at 72°C for 9 min. Then, 5 μl of the first PCR product was further amplified by nested PCR with 45 μl of the reaction mixture containing 25 pmol of plus-sense primer (5′-dTCTTCTTTTGCACCTAGAAC; NS+171; positions 172 to 191) and 25 pmol of minus-sense primer (5′-dCCTGTTTCAATTCCGGCCAC; NS−586; positions 587 to 568). The nested PCR conditions were the same as the first PCR conditions except for the primer annealing at 51°C. To exclude any possibility of contamination and to validate the amplification process of the NS gene, negative and positive controls were included with the samples for each reaction. The nested PCR products (416 bp) were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels. We then confirmed the result of RT-PCR by direct sequencing of the nested PCR products.

For the first and nested PCR of the NS gene, we used the primers that had been used for NS gene sequencing as reported previously (1, 8, 14). The primer sequences are well conserved (>95% identities) among more than 100 influenza C viruses that are registered in GenBank, and we found that influenza A (H3) viruses that circulated in 2004 were not amplified by this PCR procedure. In Hiroshima Prefecture, the PCR was performed with the hemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene primers described by Zhang et al. (24). With C/Ann Arbor/1/50, the detection limits of the PCRs for the NS gene and the HE gene were both 16 50% egg-infectious doses (EID50)/ml (data not shown).

HI test.

Clinical specimens that were found to be positive for influenza C virus by cell culture were inoculated into the amniotic cavity of 8- or 9-day-old embryonated hen's eggs because passages of influenza C virus in tissue culture cells sometimes result in selection of antigenic variants (23). These amniotic fluids were then used for the HI test with anti-HE monoclonal antibodies as described previously (12, 13).

Sequence analyses.

Based on the results of the antigenic analysis, we selected 13 representative strains, which were isolated in nine different prefectures, and determined the nucleotide sequences of the HE gene as described previously (8, 13). The coding region from nucleotides 64 to 1989 of the HE gene was sequenced by using a BigDye terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit on an ABI Prism 310 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) automatic sequencer. A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method using the PHYLIP program (version 3.573c).

Infectivity assays.

We carried out infectivity assays with clinical specimens collected at Yamanobe Pediatric Clinic in Yamagata Prefecture that were determined to be positive by cell culture or RT-PCR. They were performed by the endpoint dilution method using embryonated hen's eggs. The clinical specimen was serially 10-fold diluted in minimal essential medium, ranging from 3 to 3 × 10−6, and 100 μl of each dilution was inoculated into the amniotic cavity of 8-day-old embryonated hen's eggs. After incubation at 34°C for 3 days, the amniotic fluid was collected and tested for hemagglutination activity using 0.5% chicken erythrocytes. We used four eggs per dilution, and the infectivity titer was calculated by the Reed-Muench method.

Clinical data.

Clinical data (date of onset, age, body temperature, and diagnosis) of the children who visited Yamanobe Pediatric Clinic and were positive for virus isolation and/or genome detection were obtained retrospectively from their medical records. Statistical analysis was performed by using the StatView J4.02. A P value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in the present study have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases and assigned the accession numbers AB252153 to AB252165.

RESULTS

Detection of influenza C virus in clinical specimens by culture and RT-PCR.

During the period from January to July 2004, a total of 95 influenza C virus strains were isolated by cell culture in nine prefectures: 45 strains were isolated in Miyagi, 31 strains were isolated in Yamagata, 1 strain was isolated in Niigata, 1 strain was isolated in Fukushima, 1 strain was isolated in Saitama, 2 strains were isolated in Kanagawa, 2 strains were isolated in Osaka, 5 strains were isolated in Hiroshima, and 7 strains were isolated in Fukuoka. Influenza C virus was not isolated in either the Aichi or the Okayama prefectures. The frequencies of virus isolation in the Miyagi and Yamagata prefectures during this period were 1.4% (45 of 3,226 specimens) and 2.5% (31 of 1,263 specimens), respectively. These frequencies were equivalent to that of parainfluenza virus type 3 (1.0% in Miyagi and 4.8% in Yamagata), although they were considerably low compared to that of influenza A virus (17.8% in Miyagi and 8.5% in Yamagata).

Using RT-PCR, we then attempted to detect the NS gene from the clinical specimens that were found to be negative for common respiratory viruses by cell culture in five prefectures across Japan. As a result, a total of 29 of 1,255 specimens were found to be positive; the NS gene was detected from 18 of 498 specimens in Yamagata, 5 of 385 specimens in Niigata, 4 of 45 specimens in Okayama, and 2 of 52 specimens in Fukuoka Prefecture, though none of 275 specimens was found to be positive in Aichi Prefecture. In Hiroshima Prefecture, where RT-PCR was performed using the HE gene primers reported, 7 of 545 specimens were found to be positive. As a result, overall frequency of virus identification by RT-PCR in this period was 2.0% (36 of 1,800 specimens).

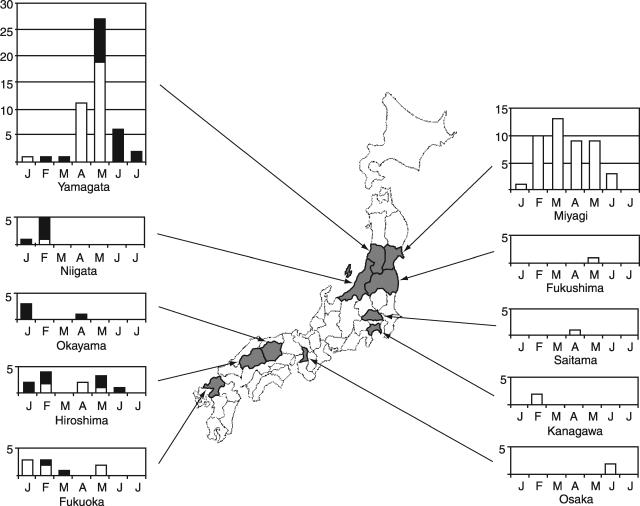

Monthly distribution of influenza C virus and clinical diagnosis as influenza-like illness (ILI).

The monthly distribution of 131 influenza C viruses detected by culture and RT-PCR in each prefecture is shown in Fig. 1. The isolation of influenza C virus continued for a 6-month period with a peak in March in Miyagi Prefecture, whereas it concentrated in April and May, and detection by RT-PCR was mainly achieved in the specimens collected in May and June in Yamagata Prefecture. In addition, isolation and/or detection of influenza C virus in the Niigata, Okayama, and Fukuoka prefectures mainly occurred with specimens collected in January or February, and in Hiroshima Prefecture it appears to have occurred with two peaks in February and May. Thus, a multiprefectural study suggested that this virus was circulating throughout Japan over a 6-month period.

FIG. 1.

Map showing the prefectures where influenza C viruses were detected and the monthly distribution of influenza C virus isolates (□) and RT-PCR positive specimens (▪) between January and July 2004. RT-PCR for the detection of influenza C virus was performed in the Yamagata, Niigata, Okayama, Hiroshima, and Fukuoka prefectures.

During the 2004 influenza season in Japan, influenza A(H3) was prevalent, with a peak in February. Of 131 detections of influenza C virus, 12 (7 were identified by RT-PCR, and 5 were identified by culture) were from patients who had been diagnosed with ILI; 4 were detected from specimens collected in January and February in Miyagi, 3 were collected in January in Okayama, 3 were collected in January and February in Hiroshima, 1 was collected in February in Yamagata, and 1 was collected in March in Fukuoka.

It might be noteworthy here that two isolates in Okayama Prefecture, which were from cases of 14-year-old boys who attended the same junior high school, were detected only by RT-PCR retrospectively, following the negative result of virus isolation. Both of them presented with symptoms of ILI, whose specimens were two of five collected at that school when a mass outbreak of influenza A or B virus had been suspected there. Thus, it became a valuable case of detection of a cluster of influenza C among older children close to adolescence, by use of RT-PCR, from whom influenza C virus isolation had been relatively rare by cell culture.

Antigenic and phylogenetic analyses of influenza C virus isolates.

The antigenicity of 87 of the 95 influenza C virus strains isolated in 2004 was examined in HI tests with anti-HE monoclonal antibodies. We previously revealed the existence of five distinct antigenic groups represented by strains Aichi/1/81, Sao Paulo/378/82, Kanagawa/1/76, Yamagata/26/81, and Mississippi/80 (13). As a result of antigenic analysis, 74 (85.1%) of the 87 strains were belonged to the Kanagawa/1/76-related antigenic group; 36 strains were isolated in Miyagi Prefecture, 22 were isolated in Yamagata, 5 were isolated in Hiroshima, 5 were isolated in Fukuoka, 2 were isolated in Kanagawa, 2 were isolated in Osaka, 1 was isolated in Niigata, and 1 was isolated in Fukushima. Nine (10.3%) strains belonged to the Yamagata/26/81-related antigenic group (six strains were isolated in Yamagata, two strains were isolated in Fukuoka, and one strain was isolated in Miyagi), two (2.3%) strains isolated in Yamagata had the antigenicity of the Sao Paulo/378/82-related antigenic group, and two (2.3%) strains belonged to the Mississippi/80-related antigenic group (isolated in Yamagata and in Saitama).

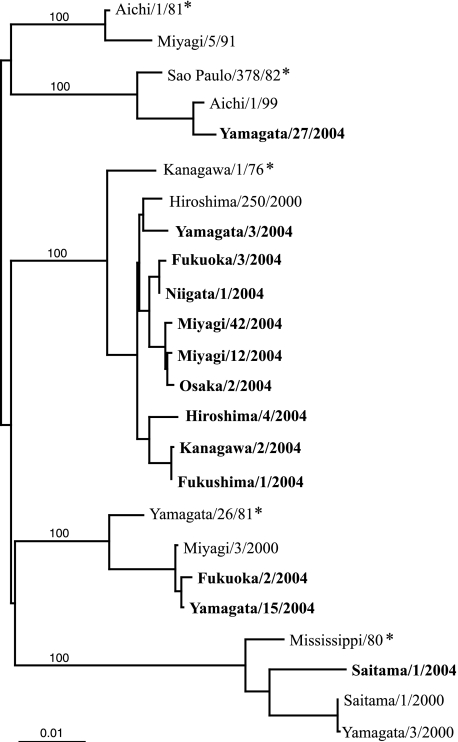

To further analyze these strains genetically, the HE gene sequence was determined for 13 strains, which were isolated in nine different prefectures, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using these sequences in addition to the 11 published sequences (Fig. 2) (2, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the influenza C virus specimens isolated in 2004 were clustered in four lineages among the five discrete lineages. One strain isolated in Yamagata (Yamagata/27/2004) was within the SaoPaul/378/82-related lineage, two strains isolated in Yamagata and Fukuoka (Yamagata/15/2004 and Fukuoka/2/2004) were within the Yamagata/26/81-related lineage, and one strain isolated in Saitama (Saitama/1/2004) was within the Mississippi/80-related lineage. The Kanagawa/1/76-related lineage was the predominant one during this season; nine strains from eight prefectures (Yamagata/3/2004, Fukuoka/3/2004, Niigata/1/2004, Miyagi/12/2004, Miyagi/42/2004, Osaka/2/2004, Hiroshima/4/2004, Kanagawa/2/2004, and Fukushima/1/2004) were part of this lineage, with sequence identities of >99.0%.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for the influenza C virus based on the coding region from nucleotide 64 to 1989 of the HE gene. Representative strains of the HE gene lineage are marked by asterisks. Viruses isolated in the present study are indicated in boldface. Numbers above the branches are the percent bootstrap probabilities of each branch determined by the PHYLIP program (version 3.573c).

Comparison of clinical specimens found to be virus positive by culture and RT-PCR.

In order to examine whether there were any correlations with detection method, we compared the characteristics of clinical specimens collected at one pediatric clinic in Yamagata Prefecture that were found to be positive by cell culture (20 specimens) with those found to be positive by RT-PCR but not by culture (18 specimens) (Table 1) . We determined the viral loads in these positive specimens, which had been stored at −80°C after primary virus isolation, by infectivity assay using embryonated hen's eggs. The amount of virus in the isolation-positive specimens was >101.48 EID50/ml in 18 of 20 specimens, whereas that in PCR-positive specimens was <100.48 EID50/ml in 13 of 18 specimens. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to type of specimen, period from onset of fever to specimen collection, or age distribution of the patients. The maximum temperature of patients in the PCR-positive group was slightly lower than that of patients in the isolation-positive group (P = 0.0301). The clinical diagnosis of upper respiratory tract illness was common in both groups and that of lower respiratory tract illness such as bronchitis and bronchiolitis was found in 4 of 20 specimens in the isolation-positive group and in 3 of 18 specimens in the PCR-positive group. Therefore, the existence of significant differences in the characteristics of the positive specimens is unlikely, regardless of the method by which the influenza C virus is detected.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of characteristics between virus isolation-positive and RT-PCR-positive specimens at a clinic in Yamagata

| Characteristics of specimens | Virus isolation-positive specimens (n = 20) | RT-PCR-positive specimensa (n = 18) | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of specimens at virus titerb: | |||

| >1.48 | 18 | 0 | |

| 0.48-1.48 | 1 | 5 | |

| <0.48 | 1 | 13 | |

| No. of throat swab/nasal aspirate specimens | 8/12 | 9/9 | 0.5359* |

| Mean period (days) from onset to specimen collection ± SD | 1.90 ± 0.79 | 2.06 ± 1.59 | 0.7001† |

| Mean age (yr) of patients ± SD | 3.90 ± 3.20 | 3.21 ± 1.76 | 0.4264† |

| Mean maximum temp (°C) of patients ± SD | 38.85 ± 0.74 | 38.35 ± 0.60 | 0.0301† |

| Clinical diagnosis (no. of patients) | |||

| Upper respiratory tract illness | 16 | 14 | |

| Bronchitis | 3 | 1 | |

| Bronchiolitis | 1 | 2 | |

| Influenza | 0 | 1 |

Specimens of isolation that were RT-PCR positive but virus isolation negative with cell culture system.

Virus titers are expressed as log10 EID50/ml.

*, chi-square test; †, two-group t test.

By re-examining the virus isolation-negative specimens collected at this clinic using RT-PCR, we were able to find an interesting case of influenza C virus infection. A child aged 1 year was diagnosed with upper respiratory tract illness, and the virus was isolated from her nasal swab in April. She attended the clinic again in May, 23 days after the former episode and was diagnosed with bronchiolitis. An additional nasal swab specimen was collected at that time, and it was negative for virus isolation and stocked, but it was later revealed to be positive for the NS gene by PCR. Genetic analysis of PCR products from these two specimens revealed a 7% difference in the 273-nucleotide length of the HE gene, suggesting that these two episodes were separate events and that we had detected the reinfection of a child with influenza C virus within a short interval.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have reported that a total of 131 influenza C viruses were detected by culture or RT-PCR in 10 prefectures across Japan during the period from January to July 2004. This strongly suggests that an epidemic of influenza C virus occurred on a national scale during this period. The frequencies of virus isolation in the Miyagi and Yamagata prefectures during this period were 1.4 and 2.5%, respectively. We recently reported that the frequency of influenza C virus isolation per total specimens from 1990 to 2004 in Yamagata and Miyagi was 0.22% (16). Comparing the frequency of isolation between January and July in each year, the highest one in the years leading up to 2004 was 0.9% in 2002 in Miyagi and 1.2% in 2002 in Yamagata, which are two-thirds and one-half that of the frequencies observed in 2004, respectively. Therefore, the frequency observed in these areas in 2004 was the highest since 1990, suggesting that 2004 was also an epidemic year for influenza C virus.

We previously revealed that genetically similar strains belonging to the Yamagata/26/81-related lineage were dominantly isolated in four Japanese prefectures (Miyagi, Yamagata, Saitama, and Hiroshima) during the 1999-2000 season (14). The results of antigenic and phylogenetic analyses in the present study also showed that antigenically and genetically similar strains belonging to the Kanagawa/1/76-related lineage were dominantly isolated in various areas of Japan in 2004, along with viruses belonging to other ones in each of the Yamagata, Fukuoka, and Miyagi prefectures. Thus, it was revealed that influenza C viruses spread over Japan in this period were mainly viruses with an HE gene belonging to the Kanagawa/1/76-related lineage.

Influenza C virus infection usually causes an upper respiratory tract illness with a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea, which is compatible with the criteria of ILI (16). Our long-term surveillance of influenza C virus has revealed that most influenza C viruses are isolated during the period from January to June (16). Thus, in winter months, influenza C coexists with epidemics of influenza A and B, and is difficult to clinically differentiate from the latter two. Moreover, the cytopathic effect in MDCK cells by influenza C virus tends to be overlooked since it is not so prominent as that caused by influenza A and B viruses. During the 2003-2004 season in Japan, influenza A(H3) was prevalent with a peak in February, whereas influenza C was detected between January and July 2004, a far longer period that extends beyond the conventional influenza season. In the present study, a total of 12 influenza C cases (7 were identified by RT-PCR, and 5 were identified by culture) were patients who had been diagnosed with ILI and whose specimens were collected during the period from January to March. This means that the RT-PCR assay could be applied to the laboratory diagnosis of influenza C during the influenza season.

We have previously described the clinical features of influenza C virus infection based on the results of isolation by culture and revealed that this virus is a significant cause of respiratory infections in children younger than 6 years of age (16). In the present study, the viral loads in the PCR-positive specimens were lower than those in the isolation-positive specimens. Although fever in the patients in the PCR-positive group tended to be slightly lower than in patients in the isolation-positive group, differences in the detection method are unlikely to have had much influence on the clinical features of influenza C virus infections. However, if RT-PCR can increase the ability to detect cases of influenza C among the lower-titer clinical specimens or in older children and adults for whom it cannot be readily isolated by cell culture, further clinical and epidemiological information concerning influenza C viruses can be obtained. As a concrete example, we detected the interesting case of a 1-year-old girl with repeat infections with influenza C virus 23 days apart, in which the virus was isolated by cell culture on the first occasion followed by a later second identification of infection by additional examination with RT-PCR on stocked virus isolation-negative specimens. We have also reported previously a case of a laboratory member with repeated influenza C virus infections within a short period (24 days apart) (9). Reinfection with influenza C virus might occur frequently (7), probably because the infection did not induce sufficient protective immunity. Further studies using RT-PCR assay might increase the opportunity to detect cases of reinfection and contribute to the understanding of the underlying factors in such cases.

In conclusion, we could detect an epidemic of influenza C virus on a national scale using a combination of cell culture and RT-PCR, but which was not easily detected by the cell culture method alone. It is expected that multi-institutional studies using the RT-PCR assay such as the present study would make it possible to obtain further information as to whether this virus can also be detected during nonoutbreak periods, as well as determine whether outbreaks of influenza C occur on a national scale every year.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alamgir, A. S., Y. Matsuzaki, S. Hongo, E. Tsuchiya, K. Sugawara, Y. Muraki, and K. Nakamura. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis of influenza C virus nonstructural (NS) protein genes and identification of the NS2 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1933-1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buonagurio, D. A., S. Nakada, U. Desselberger, M. Krystal, and P. Palese. 1985. Noncumulative sequence changes in the hemagglutinin genes of influenza C virus isolates. Virology 146:221-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claas, E. C. J., M. J. W. Sprenger, G. E. M. Kleter, R. Van Beek, W. G. V. Quint, and N. Masurel. 1992. Type-specific identification of influenza viruses A, B, and C by polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 39:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsila, M., J. Kauppila, K. Tuomaala, B. Grekula, T. Puhakka, O. Ruuskanen, and T. Ziegler. 2001. Detection by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of influenza C in nasopharyngeal secretions of adults with a common cold. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1269-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homma, M., S. Ohyama, and S. Katagiri. 1982. Age distribution of the antibody to type C influenza virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 26:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katagiri, S., A. Ohizumi, and M. Homma. 1983. An outbreak of type C influenza in a children's home. J. Infect. Dis. 148:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katagiri, S., A. Ohizumi, S. Ohyama, and M. Homma. 1987. Follow-up study of type C influenza outbreak in a children's home. Microbiol. Immunol. 31:337-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura, H., C. Abiko, G. Peng, Y. Muraki, K. Sugawara, S. Hongo, F. Kitame, K. Mizuta, Y. Numazaki, H. Suzuki, and K. Nakamura. 1997. Interspecies transmission of influenza C virus between humans and pigs. Virus Res. 48:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuzaki, M., K. Adachi, K. Sugawara, H. Nishimura, F. Kitame, and K. Nakamura. 1990. A laboratory-acquired infection with influenza C virus. Yamagata Med. J. 8:41-51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzaki, Y., Y. Muraki, K. Sugawara, S. Hongo, H. Nishimura, F. Kitame, N. Katsushima, Y. Numazaki, and K. Nakamura. 1994. Cocirculation of two distinct groups of influenza C virus in Yamagata City, Japan. Virology 202:796-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki, Y., K. Mizuta, H. Kimura, K. Sugawara, E. Tsuchiya, H. Suzuki, S. Hongo, and K. Nakamura. 2000. Characterization of antigenically unique influenza C virus strains isolated in Yamagata and Sendai cities, Japan, during 1992-1993. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1447-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuzaki, Y., K. Sugawara, K. Mizuta, E. Tsuchiya, Y. Muraki, S. Hongo, H. Suzuki, and K. Nakamura. 2002. Antigenic and genetic characterization of influenza C viruses which caused two outbreaks in Yamagata City, Japan, in 1996 and 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:422-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki, Y., K. Mizuta, K. Sugawara, E. Tsuchiya, Y. Muraki, S. Hongo, H. Suzuki, and H. Nishimura. 2003. Frequent reassortment among influenza C viruses. J. Virol. 77:871-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuzaki, Y., S. Takao, S. Shimada, K. Mizuta, K. Sugawara, E. Takashita, Y. Muraki, S. Hongo, and H. Nishimura. 2004. Characterization of antigenically and genetically similar influenza C viruses isolated in Japan during the 1999-2000 season. Epidemiol. Infect. 132:709-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuzaki, Y., K. Sato, K. Sugawara, E. Takashita, Y. Muraki, T. Morishita, N. Kumagai, S. Suzuki, and S. Hongo. 2005. Isolation of an influenza C virus introduced into Japan by a traveler from Malaysia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:993-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuzaki, Y., N. Katsushima, Y. Nagai, M. Shoji, T. Itagaki, M. Sakamoto, S. Kitaoka, K. Mizuta, and H. Nishimura. 2006. Clinical features of influenza C virus infection in children. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1229-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moriuchi, H., N. Katsushima, H. Nishimura, K. Nakamura, and Y. Numazaki. 1991. Community-acquired influenza C virus infection in children. J. Pediatr. 118:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muraki, Y., S. Hongo, K. Sugawara, F. Kitame, and K. Nakamura. 1996. Evolution of the haemagglutinin-esterase gene of influenza C virus. J. Gen. Virol. 77:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura, H., K. Sugawara, F. Kitame, K. Nakamura, and H. Sasaki. 1987. Prevalence of the antibody to influenza C virus in a northern Luzon Highland Village, Philippines. Microbiol. Immunol. 31:1137-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numazaki, Y., T. Oshima, A. Ohmi, A. Tanaka, Y. Oizumi, S. Komatsu, T. Takagi, M. Karahashi, and N. Ishida. 1987. A microplate method for isolation of viruses from infants and children with acute respiratory infections. Microbiol. Immunol. 31:1085-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada, S., K. Suzuki, K. Arai, M. Shinohara, K. Uchida, Y. Segawa, and Y. Hoshino. 2000. Influenza C viruses isolated during the 1999-2000 influenza season in Saitama prefecture, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 53:170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takao, S., Y. Matsuzaki, Y. Shimazu, S. Fukuda, M. Noda, and S. Tokumoto. 2000. Isolation of influenza C virus during the 1999/2000-influenza season in Hiroshima prefecture, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 53:173-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umetsu, Y., K. Sugawara, H. Nishimura, S. Hongo, M. Matsuzaki, F. Kitame, and K. Nakamura. 1992. Selection of antigenically distinct variants of influenza C viruses by the host cell. Virology 189:740-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, W., and D. H. Evans. 1991. Detection and identification of human influenza viruses by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 33:165-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]