Abstract

Objectives. Many county coalitions throughout California have created local health insurance programs known as Healthy Kids to cover uninsured children ineligible for public programs as a result of family income level or undocumented immigrant status. We sought to gain an understanding of the experiences of these coalitions as they pursue the goal of universal coverage for children.

Methods. We conducted semistructured telephone-based or in-person interviews with coalition leaders from 28 counties or regions engaged in expansion activities.

Results. Children’s Health Initiative coalitions have emerged in 31 counties (17 are operational and 14 are planned) and have enrolled more than 85000 children in their health insurance program, Healthy Kids. Respondents attributed the success of these programs to strong leadership, diverse coalitions of stakeholders, and the generosity of local and statewide contributors. Because Healthy Kids programs face major sustainability challenges and difficulties with provider capacity, most are cautiously looking toward statewide legislative solutions.

Conclusions. The expansion of Healthy Kids programs demonstrates the ability of local coalitions to reduce the number of uninsured children through local health reform. Such local programs may become important models as other states struggle with declines in employer-based coverage and increasing immigration and poverty rates.

Over the past decade, California has experienced major changes in the financing of health insurance coverage for families. Increasing national poverty rates, downturns in employer-based coverage, and rising immigration rates have influenced the proportion of state residents who have health insurance as well as how they obtain coverage.1,2 The most salient changes have occurred among children, for whom public program expansions have more than offset major decreases in employer-based coverage, resulting in an estimated net decrease of 117000 uninsured children between 2001 and 2003.3

Whereas approximately 8% of California children aged 0 to 18 years (a total of 782000 children) remain uninsured, an estimated two thirds are already eligible for but not yet enrolled in existing programs such as Medi-Cal and Healthy Families (California’s Medicaid and State Children’s Health Insurance Program, respectively).3 In the case of these children, the challenge is not changing policy but expanding outreach and enrollment, simplifying application processes, and increasing retention among those already covered. The remaining one third of uninsured children do not qualify for existing programs as a result of their family’s income level or, more commonly, undocumented immigration status.4

Because Medi-Cal and Healthy Families have restrictions on providing assistance to undocumented families, child health advocates have sought alternatives to ensure that the estimated 200000 or so ineligible children without coverage can obtain care. One approach that is unique to California is the formation of county-based coalitions known as Children’s Health Initiatives (CHIs). CHIs have been convened by a range of community-based organizations not only to expand outreach and enrollment for existing programs but to design new insurance programs (i.e., Healthy Kids programs) entirely separate from other public programs in an effort to cover otherwise ineligible children.

The first CHI (and the first Healthy Kids program) was initiated in Santa Clara County in 2001 by a group of community-based organizations.5 These organizations convinced the county’s supervisors to allocate funds to children’s health insurance, assembled a coalition, and began working to design a comprehensive insurance program for uninsured children. Obtaining a mix of public and private funding and contracting with the Santa Clara Family Health Plan to administer the plan, the Santa Clara CHI launched its Healthy Kids program in a period of only about 6 months. The large response to the program that followed provided the impetus for advocates elsewhere to develop similar programs. Currently, 17 counties offer Healthy Kids programs and 14 are developing such programs.

Given this major county-based movement toward universal coverage for children (including those in families of undocumented immigration status), understanding the experiences of CHIs may provide important guidance for California, as well as other states such as Illinois and Massachusetts that are aiming to expand coverage for children. We examined the progress of CHIs toward enrolling all eligible children; variations in program design, financing, and sustainability; the leadership and composition of CHI coalitions; outreach strategies; provider capacity (the availability and willingness of providers to serve Healthy Kids enrollees); and experiences with a statewide Healthy Kids legislative initiative.

METHODS

Between April and July 2005, we conducted semistructured telephone or in-person interviews with representatives from the 28 California counties or regions that were engaged in any CHI activities at the time. Three counties were not included (Napa, Placer, and Sutter) because their programs were at the earliest stages of planning, and thus most of our questions were not relevant.

Interviews were completed with the individual or individuals charged with coordinating the activities of each CHI. If coordination was a shared responsibility, group interviews were conducted with the individuals involved. Although we captured the perspectives of a total of 36 individuals, our unit of analysis remained the CHI (n = 28). Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and then reviewed by both the interviewers and respondents for accuracy. Respondents from all CHIs completed a follow-up questionnaire in January 2006 to update their enrollment, financing, and progress toward implementation status. The findings described here reflect the status of CHIs as of February 2006.

RESULTS

Current Status of CHIs

Most CHIs focused on 2 major aspects of universal coverage: increasing outreach efforts to enroll uninsured children who were eligible for Medi-Cal or Healthy Families and developing a new insurance program (Healthy Kids) for children who would otherwise be ineligible. These approaches were usually integrated in a single message delivered to the community stating that all children whose families were under 300% of the federal poverty level (as established by the US Census Bureau) were eligible for coverage.

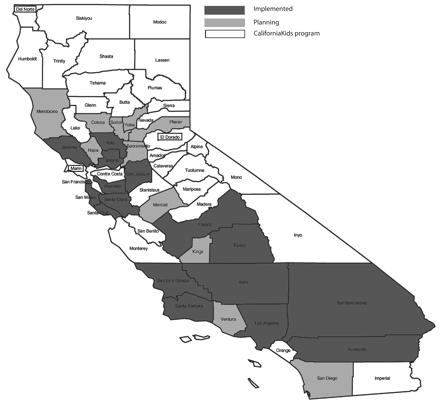

By February 2006, 17 of the state’s 58 counties had implemented a Healthy Kids program (Figure 1 ▶). Although the number of programs in operation was small, these programs were located in counties whose collective populations included more than 65% of all uninsured children in the state.6 Fourteen other counties were actively planning a CHI. Some smaller counties were developing a regional Healthy Kids program. At the time, a significant effort was under way to unite the counties of Sacramento, Colusa, El Dorado, and Yuba so that coverage could be provided through a single program.

FIGURE 1—

Status of Children’s Health Initiatives in California as of February 2006.

Three CHIs in the planning stages had opted, at least initially, to cover children through a less comprehensive program, CaliforniaKids. This nonprofit private insurance plan, available statewide and used to varying degrees in different counties, offered primary care coverage and subsidized premiums to children aged 2 to 18 years who were not eligible for public coverage as a result of their family’s undocumented immigration status or income level. The program was implemented by the CaliforniaKids Healthcare Foundation, an independent, nonprofit organization. CaliforniaKids reported having served more than 62 000 children statewide since its inception. Because the program did not cover inpatient care, however, some respondents from CHIs using CaliforniaKids (such as from Marin County) reported aiming to offer a Healthy Kids program in the future.

Healthy Kids Program Design and Benefits Structure

All CHIs have sought to replicate a Healthy Families coverage model for their Healthy Kids program, with medical, dental, vision, mental health, and inpatient coverage. In general, children aged 0 to 18 years whose families were below 300% of the federal poverty level were eligible for Healthy Kids regardless of their immigration status. Children who were already eligible for Medi-Cal or Healthy Families (the income cutoff for which is 250% of the federal poverty level) were enrolled in those programs first and foremost.

Most CHIs have established sliding premium scales and limited copayments for enrollees. In general, families paid no more than $5 to $10 monthly per child, and often rates were lower (e.g., in Riverside and San Bernardino, the cost is only $20 per year). In most counties there was a family maximum, which was generally set at the cost of covering 3 children (usually no more than $20 per month). Copayments were about $5 for primary care visits but varied somewhat across CHIs for other services such as dental care, mental health care, and emergency visits.

Finally, the presence of successful, nearly identical programs in other counties bolstered the ability of a CHI to raise support for programs that were successful rather than for untested programs.

Progress in Enrolling Children in Healthy Kids

As of January 2006, the 17 operational programs had enrolled more than 85 000 of the estimated 186000 eligible children in the study counties, reflecting an enrollment rate of 46% of eligible children (Table 1 ▶). The Los Angeles Healthy Kids program, by far the largest CHI, enrolled almost 43 000 children (about half of Healthy Kids enrollees statewide) in less than 2 years of operation, an enrollment rate of 61% of eligible children in the county. Other CHIs enrolled between 1% (Fresno, which had just initiated its program) and 83% (San Mateo) of eligible children.

TABLE 1—

Reported Number of Children Eligible for, Enrolled in, and Wait-Listed for Healthy Kids Programs: 17 California Counties, January 2006

| No. of Children Enrolled | |||||||

| County | Initiative Start Date, Year (Quarter) | Age 0–5 y | Age 6–18 y | Total | No. of Children Wait-Listeda | Estimated No. of Children Eligible | % of Eligible Children Enrolled |

| Santa Clara | 2001 (1) | 2 430 | 11 030 | 13 460 | 970 | 18 000 | 75 |

| San Franciscob | 2002 (1) | 780 | 3 400 | 4 180 | 0 | 5 000 | 84 |

| Riverside | 2002 (3) | 2 460 | 4 620 | 7 080 | 2 370 | 17 000 | 42 |

| San Mateoc | 2003 (1) | 900 | 5 010 | 5 910 | 0 | 7 150 | 83 |

| San Bernardino | 2003 (3) | 1 810 | 1 900 | 3 710 | 1 620 | 22 000 | 17 |

| Los Angeles | 2003 (3) | 7 760 | 35 180 | 42 940 | 3 970 | 70 000 | 61 |

| San Joaquin | 2003 (4) | 460 | 1 650 | 2 110 | 160 | 3 000 | 70 |

| Santa Cruz | 2004 (3) | 320 | 1 440 | 1 760 | 0 | 2 300 | 77 |

| Kernd | 2004 (4) | 100 | . . . | 100 | . . . | 2 000 | 5 |

| San Luis Obispo | 2005 (3) | 140 | 350 | 490 | 90 | 2 200 | 22 |

| Alameda | 2005 (3) | 30 | 550 | 580 | 0 | 11 000 | 5 |

| Santa Barbara | 2005 (4) | 50 | 130 | 180 | 0 | 4 000 | 5 |

| Fresno | 2005 (4) | 30 | 70 | 100 | 0 | 8 550 | 1 |

| Tulare | 2006 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 930 | 6 800 | 0 |

| Solano | 2006 (1) | 110 | 750 | 860 | 0 | 2 000 | 50 |

| Sonoma | 2006 (1) | 340 | 1 360 | 1 700 | 100 | 2 700 | 63 |

| Yolo | 2006 (1) | 10 | 40 | 50 | 0 | 2 350 | 2 |

| Total | . . . | 17 730 | 67 480 | 85 210 | 10 210 | 186 050 | 46 |

Note. Enrollment and wait-list counts were rounded to the nearest 10, except for number of children eligible, which was rounded to the nearest 50. Except where otherwise noted, eligibility criteria were children aged 0 through 18 years and family income less than 300% of the federal poverty level according to the US Census Bureau.

aNo program reported a wait-list for children aged 0 through 5 years.

bAge of eligibility was extended in San Francisco to 0 through 24 years.

cIncome eligibility was 400% of the federal poverty level.

dAge of eligibility was 0 through 5 years.

Some CHIs have had to cap their enrollments because of large program turnouts and limited funding. Most of the capped programs have formed wait-lists so that as older children graduate from the program or children drop out, other children can be quickly enrolled.7 Among the 17 operational programs, 7 had a wait-list; wait-list counts ranged from 90 children in San Luis Obispo to 3970 in Los Angeles and totaled 9280 children statewide.

The wait-lists included only children aged 6 to 18 years because funding from First 5 organizations has been sufficient to cover all eligible children 0 to 5 years of age. First 5 organizations are state and county organizations that were created in 1998 through the California and Families First Act (Proposition 10), which allocated funds from a tobacco tax to services designed to improve the health and development of children aged 0 to 5 years. Although state and county First 5 organizations are independent from one another, First 5 California (the state-level organization) usually matches the contributions of local funds to CHIs at a rate of about $1 for every $4 spent locally on insurance premiums for children 0 to 5 years old.

Retention efforts in Healthy Kids have been moderately successful, with respondents from most of the operational CHIs reporting retention rates of 70% to 85%. Retention is a challenge considering that many CHI enrollees are members of migrant families that change addresses frequently. Respondents reported using a variety of strategies to address retention, including sending renewal forms well in advance of the renewal date, sending advance reminders with prepaid change of address cards, engaging in aggressive outreach efforts by telephone, and allowing reenrollment by telephone.

Program Financing and Sustainability

Most respondents reported that in their counties the cost of health insurance coverage for 1 child is approximately $80 to $120 per month ($960 to $1440 per year). Nonetheless, each CHI must raise substantial funds (including funds for administrative costs and outreach and enrollment activities) to offer coverage to eligible children, often from piecemeal sources. Although local health departments and philanthropic organizations have often rallied to provide support, some CHIs faced major challenges in obtaining adequate funding.

By June 2005 (the month of our financing survey), the 9 CHIs that were operational as of that point had raised a total of nearly $330 million to fund their programs. Most of these funds (84%) directly subsidized premiums, with the remainder allocated to planning, administration, or outreach and enrollment. First 5 organizations have been the primary financial supporter of CHIs,8 accounting for a striking 42% of total funding statewide. Health plans account for 27% of total funding, but this source exists in only 5 counties. Philanthropic organizations account for 12% of funding, and county funds (11%) and tobacco settlement funds (8%) account for most of the remaining dollars.

Nonetheless, CHI coalitions are concerned about the sustainability of their programs. More than one third of respondents (37%) reported not having enough funding to continue covering the same number of children during the following fiscal year. About one quarter (27%) reported having funding for approximately 1 to 2.4 years in the future, and 36% had enough funding for 2.5 years or more. Because of the longer-term commitments from First 5 organizations, funding for children 0 to 5 years of age is usually more secure than funding for children 6 to 18 years old. San Francisco is a unique case, having committed ongoing city funds to cover all children.

Steady March to Universal Coverage

The growth of CHIs has been aided by a large degree of informal sharing of local experiences across counties. Many coalition members have consulted with representatives from Santa Clara and the other counties that were among the first to implement CHIs. As these programs grew, California philanthropic organizations that were early financial supporters began facilitating this process by convening grantees and interested county representatives considering similar programs. Our respondents also reported that the availability of technical assistance groups (funded by philanthropic organizations as well) was essential throughout the process of development.

Despite this extensive sharing of experiences, progress toward implementation in individual counties has not necessarily been expedited over time. Of the first 7 counties to implement a CHI, 6 required 9 months or less to become operational. As mentioned, Santa Clara needed only 6 months to begin enrollment. By contrast, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Fresno required 2 years or more. Although this situation may seem counterintuitive—given that forerunners would be expected to streamline a path for other counties to follow—there are several potential contributing factors.

Some of the earliest CHIs had relatively large amounts of political support and, in some cases, access to ready and willing financial contributors. In addition, several of the early CHIs were formed out of existing health care coalitions that simply transferred their focus to children’s health insurance coverage. Most of the early CHIs also had a readily available managed care plan serving Medi-Cal enrollees that was able to offer a Healthy Kids product. In Riverside, San Bernardino, Los Angeles, and San Joaquin, health plans were actually coconveners of CHIs. San Joaquin is unique because Healthy Kids was quickly launched by the health plan, the county, and the local First 5 organization; only later was a full CHI coalition established to gather broader public support for the program.

Leadership of CHI Coalitions

Many CHIs have reported difficulties in establishing or implementing Healthy Kids. For example, according to the respondents representing the San Diego and Ventura CHIs, the boards of supervisors in those counties were interested in ensuring coverage for children, but San Diego policies restrict expenditures of county funds on undocumented immigrant populations, and the Ventura supervisors supported expanding coverage but without the use of county dollars. Overcoming such barriers, which were reported in varying degrees by most respondents, required strong leadership.

Organizations charged with leadership of CHIs were frequently very influential in their respective counties, and they commonly played a major role in Healthy Kids programs other than by providing coordination (e.g., providing funding or leading outreach and enrollment activities). In more than half of the CHIs, the health department (26%) or a county First 5 organization (26%) convened the program. Managed care plans convened 14% of the CHIs statewide, and some CHIs had been initiated by multiple organizations.

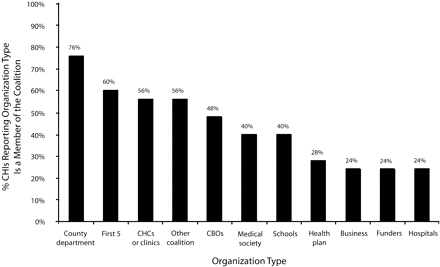

Diversity of CHI Coalition Stakeholders

One of most consistent findings across the CHIs was the reported importance of developing a broad coalition of stakeholders to provide guidance in the design and operation of the initiative. Although no 2 CHI coalitions were the same, most had assembled a common array of stakeholders (Figure 2 ▶) that had helped shape the program, integrate the program within existing public and private health systems, raise critical funding, rally public and policymaker support, and communicate the program to potential clients and providers.

FIGURE 2—

Percentages of Children’s Health Initiatives reporting coalition stakeholder participation (n = 27): California, 2006.

Note. CHCs = community health centers; CBOs = community-based organizations.The Sacramento regional initiative was excluded.

Overall, county health departments and child advocacy organizations were among the most common CHI coalition participants; representatives from medical groups and hospitals were more hesitant to join. Three quarters (76%) of our respondents reported that the health department participated, and county First 5 organizations were active in 60% of the CHIs. More than half (56%) of CHIs had community clinics represented, but hospitals (28%) and health plans (24%) each participated in only about one quarter of CHIs.

The presence of a broad CHI coalition was not, however, a singular determinant of developing a successful program. Just 3 organizations were represented in San Francisco’s coalition—the city health plan, the mayor’s office, and outreach workers—yet this city’s Healthy Kids program was one of the earliest to be initiated. The CHI coalition meets only once per year, but the city and county (which nearly alone funds the program) has committed to allocating the necessary budget to cover all children every year.

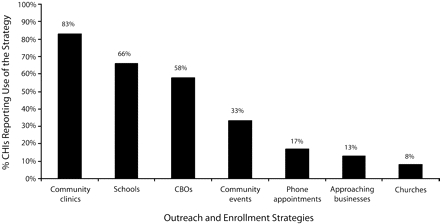

Outreach and Enrollment Strategies

CHIs had emphasized outreach and enrollment to ensure that children eligible for MediCal and Healthy Families enroll. Some CHIs had reported enrolling approximately 2 children in either Medi-Cal or Healthy Families for every child enrolled in Healthy Kids.9 The most commonly reported strategy for enrolling children in all 3 programs, mentioned by 83% of respondents (Figure 3 ▶), was through community clinics and health centers. Because these clinics and centers were often already serving many uninsured families, several CHIs have termed this strategy “in-reach.”

FIGURE 3—

Percentages of Children’s Health Initiatives (CHIs) reporting Healthy Kids outreach strategies (n = 24): California, 2006.

Note. CBOs = community-based organizations. Colusa, Merced, Sacramento, and San Diego, which were not involved in CHI outreach activities at the time of the study, were excluded.

Schools were also a common setting for conducting outreach. About two thirds of respondents reported distributing informational inserts in back-to-school packets, conducting presentations at school events, and setting up booths during sign-ups or school fairs. Few reported attempts to have parents complete applications at school events, noting the low yield resulting from parents often not being prepared with the necessary information. More commonly, outreach workers made appointments with parents who expressed an interest.

Challenges to Provider Capacity

Because most CHIs had selected health plans with existing Medi-Cal and Healthy Families provider networks to serve Healthy Kids enrollees, the impact of these programs on provider capacity was minimal. Rather, most CHIs reported existing problems with capacity that were magnified somewhat by new programs. More than half (57%) of the respondents reported difficulties with provider capacity. Respondents most commonly reported capacity problems associated with specialists and primary care providers (both reported by 36% of respondents); 14% reported problems with dental capacity. Among the respondents reporting a problem with provider capacity, almost half (42%) indicated that the main reason was reimbursement.

Local Ambitions and the Statewide Legislative Initiative

Building on the momentum of CHIs and recognizing the large and looming problems with future program sustainability, child health advocates developed legislative proposals to unite CHIs through a statewide Healthy Kids program using state funding. In early 2005, bills in the state assembly and senate (AB772 and SB437) found legislative sponsors. AB772 and a corresponding financing bill, AB1199, passed the senate and assembly, but both were ultimately vetoed by the governor.10

Approximately 70% of CHIs formally expressed support for a statewide program, but only 41% of respondents reported actively supporting the initiative (e.g., participating in statewide planning meetings and testifying before policymakers). Respondents acknowledged that although a well-funded statewide program would help resolve major sustainability concerns, it would come at the cost of losing local control. A majority (52%) of the respondents reported concern about whether a statewide program could maintain the efficient outreach and retention processes that the CHIs have already implemented.

Specifically, approximately one third of the respondents reported concern that a statewide program would increase bureaucracy, paperwork, and regulations while providing the same level of coverage now being provided by the CHIs. About one quarter (26%) of the respondents reported being concerned that successful local enrollment processes would be replaced with more top-down approaches and less efficient enrollment procedures. A smaller percentage reported concerns about opening up the program to competing health plans (15%) and sharing private information about undocumented immigrant children with the state (7%).

DISCUSSION

Taken together, local efforts to expand health insurance coverage for uninsured children through Healthy Kids programs have become a major and unique health policy movement in California. By covering more than 85 000 children through new publicly and privately funded programs and enrolling many more children in Medi-Cal and Healthy Families, CHIs have demonstrated the ability of community-based coalitions to accomplish progressive health policy reform. Even as immigration issues continue to divide state governments and the federal government, CHIs have successfully mobilized communities in an effort to ensure that children, regardless of their immigration status, are eligible for health insurance coverage.

Since this study was conducted, more counties have launched Healthy Kids programs, and California has inched closer to universal coverage for children. As of January 2007, 22 counties were offering Healthy Kids coverage, and 6 more counties were in the planning stages to provide coverage. Counties that have not yet formed a CHI may indeed still do so, especially as neighboring counties come online and demonstrate the potential of the program. Some counties, however, will probably continue to face major barriers to initiating a CHI, especially in areas where anti–illegal immigration sentiment runs high, where managed care plans do not serve Medi-Cal, and where local funding resources are few.

Nonetheless, there are several important lessons that existing, planned, and even future CHIs can learn from this analysis. First, CHIs benefit from strong leadership and having a diverse coalition of stakeholders that help obtain a broad base of public, political, and financial support. Second, sharing experiences across counties provides critical guidance in designing programs, reducing the need to “reinvent the wheel.” Third, the presence of foresighted local contributors (such as First 5 organizations) that will commit to long-term funding is not a guarantee, so CHIs should make efforts early in the process to obtain as broad a base of long-term financial support as possible.

Major challenges remain for California’s CHIs. First, most of these initiatives currently or will soon face large financial sustainability problems. Although generous philanthropic organizations and other funders continue to provide financial support, there is no guarantee that this support will not cease as new health issues emerge and gain popularity. In addition, piecemeal funding sources simply cannot reduce the need for longer term support from broader state and federal sources. A statewide effort to create a Healthy Kids program continues to have wide public and political support,11,12 but concerns continue to be raised by stakeholders regarding expenditures of public funds on undocumented immigrant children. An initiative qualified for the November 2006 ballot that proposed an increase in funding for Healthy Kids programs through a higher state tobacco tax, but this measure was narrowly defeated.13

Second, even though there is now nearly universal coverage in many California counties, enrollments in Medi-Cal, Healthy Families, and Healthy Kids programs are still lower than they should be. Much of this discrepancy continues to be due to problems associated with a lack of outreach and enrollment efforts designed to inform families of the programs; however, other factors are also likely to be involved, including complicated application and enrollment procedures, confusing program eligibility requirements, and, potentially, the stigma associated with many public programs.

Although national programs such as Covering Kids and Families (funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) have helped support state coalitions addressing some of these issues,14 more is needed to streamline the process of enrolling and retaining families in public programs. The recent increase of $72 million for outreach and enrollment into Medi-Cal and Healthy Families approved in the 2006–2007 California state budget15 may provide counties with some level of assistance, but these issues will continue to represent a major challenge for CHIs.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared as part of our ongoing evaluation of the Covering California’s Kids program, funded by the California Endowment (grant DCA 20041455).

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Maxanne Hatch in conducting and analyzing many of the interviews and site visits with the Children’s Health Initiative respondents. We also thank Dolly Yang and Laura Barrera, who assisted with the interview transcriptions, and Cindy Benitez for her review of the article. We would especially like to thank the many representatives of the local Children’s Health Initiatives who generously agreed to be interviewed for this study.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Sciences Campus institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from respondents.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors G. D. Stevens and M. R. Cousineau originated the study and designed the analysis plan. K. Rice assisted with the data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results. All of the authors contributed to the preparation of the article.

References

- 1.Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance in the United States: 2004. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005.

- 2.Brown ER, Lavarreda SA. Job-Based Coverage Drops for Adults and Children but Public Programs Boost Children’s Coverage. Los Angeles, Calif: University of California at Los Angeles, Center for Health Policy Research; 2005. [PubMed]

- 3.Brown ER, Lavarreda SA. Children’s Insurance Coverage Increases as a Result of Public Program Expansion. Los Angeles, Calif: University of California at Los Angeles, Center for Health Policy Research; 2004.

- 4.Stevens GD, Seid M, Halfon N. Enrolling vulnerable, uninsured but eligible children in public health insurance: association with health status and primary care access. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e751–e759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong L. Universal health care for children: two local initiatives. Future Child. 2003;13:238–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.California Health Interview Survey. Available at: www.chis.ucla.edu. Accessed January 15, 2006.

- 7.Frazer H, Schnyer C, Wong L. Challenged by Their Success: Healthy Kids Program Enrollment Caps and Waiting Lists. San Mateo, Calif: Institute for Health Policy Solutions; 2005.

- 8.Frazer H, Wong L, Schnyer C. First 5 Commissions: Key Partners in Children’s Health Initiatives. San Mateo, Calif: Institute for Health Policy Solutions; 2005.

- 9.Howell E, Hughes D, Stockdale H, Kovac M. Evaluation of the San Mateo County Children’s Health Initiative: First Annual Report. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2004.

- 10.Schwarzenegger vetoes bills to expand Healthy Kids programs, signs other health-related legislation. Available at: http://www.californiahealthline.org. Accessed January 8, 2007.

- 11.Politics of Insuring California’s Children: Dissenting Views on a Common Goal. Los Angeles, Calif: University of Southern California, Division of Community Health; 2005.

- 12.Californians Overwhelmingly Support Plan to Provide Health Coverage for Every Child. Woodland Hills, Calif: California Endowment; 2005.

- 13.Lauer G. Groups look to tobacco tax increase for health care funding. Available at: http://www.californiahealthline.org. Accessed January 8, 2007.

- 14.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Covering Kids and Families. Available at: http://coveringkidsandfamilies.org/. Accessed June 15, 2006.

- 15.Schwarzenegger previews budget proposal, including $72.2M increase for children’s health insurance programs. Available at: http://www.californiahealthline.org. Accessed January 8, 2007.