Abstract

The Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center will open soon, replacing the county’s current 74-year-old facility with a modern, although smaller, facility.

Los Angeles County has provided hospital care to the indigent since 1858, during which time, the operation of public hospitals has shifted from a state-mandated welfare responsibility to a preeminent part of the county’s public health mission. As this shift occurred, the financing of Los Angeles County hospitals changed from primarily county support to state and federal government sources, particularly Medicaid.

The success of the new hospital will depend on whether government leaders at all levels provide the reforms needed to help the county and its partners stabilize its funding base.

LOS ANGELES COUNTY hospitals are among the nation’s notable public health achievements. More than 150 years after it first provided hospital care for the indigent, Los Angeles County is about to open a new hospital, replacing its 74-year-old and earthquake-damaged Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC–USCMC) with a modern, although smaller, facility.

The current LAC–USCMC hospital is among the largest in the state and the centerpiece for health care in Southern California. It operates a busy trauma center and an array of primary and specialty clinics and is affiliated with the University of Southern California, which has operated a medical school there since 1885.1

Annually, the hospital receives nearly 800000 emergency and outpatient visits and more than 46000 inpatient admissions. LAC–USCMC patients, like other Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (DHS) patients, are primarily poor and uninsured. More than three quarters are living below the federal poverty level, more than 70% are Latino, two thirds are uninsured, and almost two thirds were born outside of the United States.2

The hospital’s public role goes beyond serving as a safety net for the poor. It has trained thousands of physicians, nurses, and other health professionals. It provides one third of all trauma care in the county and has been the site of many significant scientific contributions in clinical medicine and surgery.3 The hospital has even been used as a visual backdrop for a popular daytime television drama. Yet, from its earliest days, it has been in the forefront of real-life controversy and political drama, as the County of Los Angeles has struggled to keep its health care system afloat.4

The Los Angeles County story is more than the history of a single hospital; it is indeed a chronicle of a community’s complex and contentious struggle to shoulder the burden of health care for its indigent and uninsured population. Other communities have similarly struggled to protect their public health and hospital systems, which reflect the historical role of public hospitals in confronting local problems associated with poverty, immigration, and lack of access to health care.5

The Los Angeles County hospital system was built under changing and sometimes conflicting social policies governing both public health and welfare for the poor. Although public health laws contributed to the evolution of the DHS, the Los Angeles County hospital emerged largely from the county’s responsibility to provide for the health and welfare of its indigent population. The Pauper Act of 1855, adopted shortly after California achieved statehood, evolved to become Section 17000 of the state Welfare and Institutions Code. Passed in 1935, Section 17000 delegated the health and welfare responsibilities of the indigent to the counties.6 Counties appropriated a portion of their tax base to health care, and by 1966, 66 public hospitals were distributed across all but 9 of the 58 counties.7

Los Angeles County’s health care system began in 1856, when 6 Daughters of Charity of St Vincent DePaul traveled to Los Angeles from Emmitsburg, Md, to open a hospital.8 Their 8-bed facility later became St Vincent’s Hospital, from which the county purchased medical services for indigent patients at a cost of $1.22 a day. It was not long before the cost of caring for the indigent became an issue in Los Angeles, and in 1878, the county opened its own 100-bed Los Angeles County Hospital and Poor Farm as a way of lowering costs to the county.9

BALANCING PUBLIC HEALTH AND INDIGENT CARE

Until 1915 public health activities and administration were centered primarily in the city of Los Angeles, which had operated a health department since 1879. The city’s first health officer, Walter Lindley, used his office to attract health seekers, individuals who might be lured to Southern California by its warm climate and lifestyle.10 Families from the East Coast and Midwest came to Southern California, and the population surged. The growing economy also attracted immigrants from Asia and Mexico, who came to Los Angeles searching for employment opportunities.11 New communities of immigrants formed outside the city limits of Los Angeles. High rates of infant mortality and infectious disease were reported in the media and discussed by both city and county officials. Residents’ fears of communicable disease grew as the number of immigrant families in the area grew, introducing a new dimension to the struggle to expand, and later protect, the Los Angeles County hospital system.

The Los Angeles County General Hospital played important roles in the treatment and control of infectious diseases.12 Many communicable-disease patients were treated at the facility. During an outbreak of plague in 1924, it was county hospital pathologist George Manor who identified the deadly bacterium in a county hospital patient.13 But during this period, the county hospital could do little to prevent the spread of infectious disease in the county or even respond to the demand for patient care in the outlying regions of Los Angeles. In 1915, the Los Angeles County Public Health Department, which had jurisdiction over smaller cities and unincorporated regions, appointed John Larabee Pomeroy, who, as the county’s first health officer, confronted high infectious-disease rates among immigrant families.14 Pomeroy developed a series of 12 free health clinics strategically placed throughout the county that would provide a new front against communicable diseases and alleviate some of the patient care demands at the county hospital.15 However, throughout the early years of the depression, private physicians in the county opposed these clinics, fearing they would draw paying patients away from their offices. Under this pressure they were closed by the county’s Board of Supervisors.16 Poor and immigrant families in Los Angeles had little access to private health care, however, and with the growing concern that immigrants would spread infectious diseases to others, physicians eventually dropped their opposition, facilitating the expansion of public health clinics in the 1940s and 1950s.

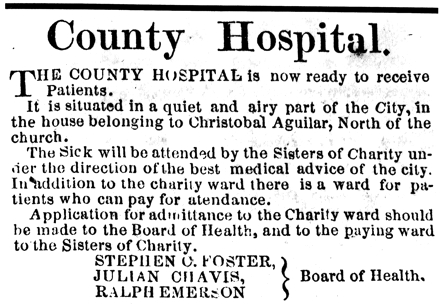

An advertisement announcing the opening of the Los Angeles County Hospital.

Source. Southern Vineyard, no. 11, June 5, 1958. Reproduced with permission from the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery.

The growing rates of infectious diseases contributed to Los Angeles County’s decision to build a new facility in the 1920s. Infectious diseases even influenced the design of the new facility, with its vertical stacks of wards separated by stairwells and elevators to reduce the flow of patients, visitors, and staff, and the spread of infectious agents.

Fear of communicable diseases did not ease the concerns of taxpayers, who were wary of the cost of building the new hospital. An initial bond measure failed and a second narrowly passed in 1923, authorizing a $5 million bond, later augmented by a 10-cent property tax surcharge, to acquire the land and construct the hospital. The hospital’s 8-ton cornerstone was dedicated by actress Mary Pickford on December 7, 1930, and the 1680-bed Los Angeles County General Hospital opened in December 1933. Its size was 1 million square feet, and its cost was $12 million. Before the formal dedication of the hospital, the Los Angeles Evening Herald wrote on March 12, 1934, “Cream-white in the noonday sun—gold tinted in the afternoon haze, looming black against the stars at night—the Los Angeles County General Hospital rounds a hilltop with its soaring mass of concrete, the greatest single monument to that command ‘Heal the sick’ ever erected by an American community.”17(p112)

HEALTH AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES

As infectious diseases subsided, many of the LAC–USCMC campus facilities and ancillary hospitals built to treat infectious disease were converted to provide general acute care or even specialty care. Several miles south of LAC–USCMC, Rancho Los Amigos was started in 1890 as a poor farm (county-run residences where paupers were supported at public expense) and became an internationally recognized rehabilitation institute, but only after the poliomyelitis epidemic pressed it into service as a respiratory center. Changes in types of health problems facing Los Angeles were not the only factors affecting change in public hospitals. Facilities were added or expanded in response to changing demographic and social forces and events. In 1942, the capacity of the county hospital was expanded to nearly 3800 beds to accommodate injured military personnel returning from World War II. At the end of the war, the county acquired 2 military hospitals: Harbor General Hospital in Torrance (now Los Angeles County/Harbor UCLA Medical Center) and a hospital in Long Beach, which was later closed. A 265-bed psychiatric hospital was built next to the General Hospital in 1955 in part as a response to the closures of state psychiatric hospitals. New educational institutions became part of the Los Angeles County Hospital, including the College of Medical Evangelists, which later moved to Loma Linda University, and the California College of Medicine, which moved to become the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine.

Postwar population growth in Los Angeles County and suburbanization had a profound impact on Los Angeles and its health care system. Up to this time, the General Hospital served not only the poor but also some of the middle-income working class who lived in central and east Los Angeles. These communities were thriving, with industries, jobs, and neighborhoods with single-family dwellings. During the postwar population surge of the 1950s, industries, jobs, and money followed the mostly White families to the growing suburban communities. The previously prospering central and east Los Angeles communities became home to a growing number of low-income families who were predominantly Black and Latino.

As employment-related, private health insurance expanded and private hospitals were built to serve growing middle-class suburban communities, health care for the poor became the prominent domain of the Los Angeles County General Hospital. By the 1960s, the hospital had become a medical complex that included the General Hospital, the Pediatric Pavilion, the Psychiatric Hospital, and the Women’s and Children’s Hospital. It was renamed the Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center.

The social and economic neglect of south-central Los Angeles, capped by police racism, culminated in urban unrest and the Watts riots of 1965, a seminal point in the history of Los Angeles. An independent commission’s report on the causes of the Watts riots identified the lack of health care in south-central Los Angeles and led to the building of the Martin Luther King Jr Medical Center and the Charles R. Drew Postgraduate Medical School (later to become the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science), both opening in 1972.18

As public hospitals in Los Angeles expanded medical services to the poor, core public health activities remained a separate entity. However, the lines between indigent health care and public health began to blur in the 1960s with the merger of the Los Angeles City Health Department into the County Health Department.19 In 1972, in further efforts to consolidate and integrate county services, the county departments of hospitals, public health, and mental health and the County Veterinarian’s Office were merged into the DHS. Integration promised a rational system of health planning whereby the deployment of health services would be based on demographic data or health status. But this approach was overcome by the increasingly political nature of the county health care system. Individual supervisors focused on problems in their own jurisdictions rather than in the larger system. Regional planning was increasingly organized according to the district boundaries of the 5-member County Board of Supervisors.20

COUNTY SUPPORT SHIFTS TO THE STATE AND FEDERAL GOVERNMENTS

County politics governed public health care through the 1950s. Patient fees made up a sizeable portion of the revenue for the Los Angeles County Hospital, although they were augmented with operating subsidies from the county. As new medical technology was added, hospital costs increased significantly and per diem costs (including physicians’ services) grew from about $4 per day in 1937 to $450 per day in 1978.21 Although other jurisdictions closed or sold their hospitals, Los Angeles turned to higher levels of government for help, beginning a shift from a largely county-financed system of care to one with significant participation from the state and federal governments.

This shift began in 1965 with the passage of Title XVIII and Title XIX of the Social Security Act, which created Medicare and Medicaid. These programs promised better access to private or mainstream medical care for the elderly and the poor. It was also hoped that these programs would help to stabilize the increasingly cash-strapped public hospital system.21 Unfortunately, these hopes were never realized. The proportion of patients aged 65 years or older who were hospitalized in Los Angeles County hospitals declined from about 21% in 1965 to less than 6% by 1968 and now runs about 3%. The substantial revenues derived from Medicare by private sector hospitals did not help Los Angeles County hospitals.23

More hope was placed on Medicaid (called Medi-Cal in California), because it was designed specifically for the poor, who composed an increasingly large proportion of county patients. Medi-Cal compensation for hospital care was so low at first that it was not attractive to private hospitals. Over time, increases in Medi-Cal hospital reimbursement rates expanded private hospital participation, which in turn led to a steady decline in Medi-Cal admissions in Los Angeles County hospitals.

A further shift from dependence on county to state revenue was imposed by the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978, which limited property taxes to no more than 1% of assessed valuation and limited annual increases in assessed valuation to no more than 2%.24 The resulting sharp decline in property tax revenue drastically cut local government budgets, exacerbating an increasingly precarious funding platform for California’s county hospitals.24

The original Los Angeles County Hospital building, 1897.

Reproduced with permission from Helen Eastman Martin

Throughout California, the success of Medi-Cal and Medicare in improving access to private care, along with Proposition 13, accelerated the closure or sale of many county hospitals. By 1985, fewer than half the counties in California operated public hospitals.26 Similar trends were noted nationally: between 1985 and 1995, the number of public hospitals in the United States declined by 14%.27 The financial problems triggering this decline in other jurisdictions similarly affected Los Angeles County. The county’s policy efforts turned increasingly to institutional survival, as its health budget was strained by dwindling revenue and an unprecedented expansion in the demand for care in its hospitals.

Registering patients at the Los Angeles County Hospital Outpatient Department, circa 1920.

Reproduced with permission from Helen Eastman Martin

Beginning in 1980, Los Angeles County encountered a series of budget crises precipitated by Proposition 13. The county turned to the state, which then had a budget surplus. In response, the state developed a complex formula for returning some of the state surplus dollars to the counties.28 By increasing their financial dependence on the state, county health systems became increasingly sensitive to changes in state policy and politics. The state imposed a maintenance-of-effort provision on the counties as a condition of state support and adopted legislation requiring public hearings to show that any proposed health care reductions or closures would not deleteriously affect the health of the public.29

Yet state support for the Los Angeles County health system was anything but stable. Over the next 20 years, the state would continually modify and realign the amount it provided to Los Angeles County, the funding sources supporting state allocations, and the expectations for maintaining the most recent level of care to the indigent.30

State support declined when the California surplus turned to a deficit in the 1980s. As the state adapted to voter-imposed spending limits and identified solutions to an alarming increase in spending for health care, the governor and California legislature sought to reduce payouts to the counties. The counties argued that unless the state did more to help them pay for indigent health care, they alone could do little to keep county hospitals open.

In 1982, in an effort to both reduce state budgets and help Los Angeles County, California eliminated the optional and entirely state-financed Medically Indigent Adult eligibility category for Medi-Cal. The state returned a portion of its projected annual expenditures for this population to the counties as a block grant. As a result, hundreds of thousands of low-income residents became uninsured; many of these had chronic health and mental health problems. Los Angeles County used the money to shore up its ever-growing health care budget deficit, although the health of the indigent adult population deteriorated in the following years.31 Because the state continually reduced the Medically Indigent Adult allocation, the action actually contributed to the county’s long-term problems. By the mid-1980s, the LAC–USCMC was again being challenged by unprecedented increases in demand for care, particularly in its emergency room.32

MEDI-CAL PATIENTS AND DOLLARS SHIFT TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR

The patient care crises at the LAC–USCMC caused alarm throughout the state. Locally, a coalition of stakeholders was formed to identify new ideas for caring for the county’s indigent population, which by 1992 had grown to 2.7 million people, 31% of the nonelderly population.33 But California had its own budget problems. In 1992, in the depths of a recession, the legislature and governor claimed $3 billion statewide from property tax revenues, $1 billion of which came from Los Angeles County. The state also targeted Medi-Cal, which was assuming an increasingly large share of the state’s budget. Under DHS director Robert Gates, Los Angeles County developed unique responses and programs to minimize the effect of these changes on its health care system. However, these changes accelerated the decline in Medi-Cal patients and revenue to the county hospital system in Los Angeles.

Beginning in 1993, California moved many of its Medi-Cal recipients into managed care. MediCal patients in Los Angeles had to choose between a commercial plan, HealthNet, and a new quasi-public local initiative called LA Care Health Plan.34 For those who did not choose a plan, the state established a formula that proportionately directed beneficiaries into all contracted health plans. Fearing a wholesale loss of Medi-Cal revenue, LA Care adopted an alternative policy, directing Medi-Cal members who did not voluntarily choose a plan to the Los Angeles County health system by default, thereby guaranteeing a revenue stream to the county health system.35

Los Angeles County developed other creative fixes to its financial problems. It helped to pass 2 state laws, SB 1255 and SB 855, that set in motion the joint state and federal Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program. DSH uses a complex, intergovernmental transfer of local, state, and federal funds and provides supplemental payments to both public and private hospitals that serve large numbers of Medi-Cal and uninsured patients.36 Although the DSH program was important to the county health budget, it further encouraged the shift of Medi-Cal patients and revenue to the private sector, which was more than willing to take patients who brought the DSH supplement but less able or willing to serve the uninsured. By 2000, indigent or uninsured patients used more than 35% of county inpatient days, compared with fewer than 5% in private Disproportionate Share Hospitals.37

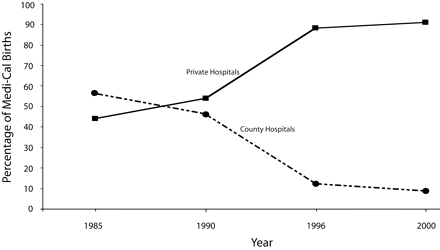

The county’s effort to protect its hospitals occasionally overlapped with its efforts to respond to public health problems. In the early 1990s, a spiraling birth rate caused overcrowding in both public and private hospitals. In response, the state expanded Medi-Cal and developed other programs for pregnant women. To ease overcrowding and facilitate access, Los Angeles County developed its own program, which immediately presumed all pregnant women were eligible for Medi-Cal and guaranteed payments to hospitals for deliveries even before a woman had been enrolled. Private hospitals now openly competed for Medi-Cal patients. This improved access for obstetrical care for lower-income women and helped relieve overcrowding in obstetrical units, but it did little to help the county hospitals financially. The percentage of Medi-Cal births in Los Angeles County hospitals plummeted. In 1985, more than half of all Medi-Cal births in the county were at county hospitals, but this dropped to fewer than 10% by 2000, while private hospitals’ share of Medi-Cal births soared to more than 90% (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Comparison of the percentage of Medi-Cal births in Los Angeles County in public and private hospitals: California, 1985 to 2000.

Note. Hospital discharge data available through the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (www.oshpd.ca.gov/HQAD/Hospital/hosputil.htm).

THE NEAR COLLAPSE OF THE COUNTY HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

By 1994, a perfect storm was brewing. The county’s $2.5 billion health budget had become unstable, and Los Angeles County hospitals increasingly found themselves alone in serving the growing number of indigent and uninsured patients, which set the stage for the now-notorious 1995 health care crisis. One third of the department’s total revenue was at risk, threatening the financial solvency of the entire County of Los Angeles. With declining Medi-Cal dollars, the county health care budget remained dependent on state and federal revenue, which was leveraged by what few dollars Los Angeles County contributed. Moreover, the DSH program tied the solvency of many urban private hospitals to county financing. Los Angeles County found it could do little to solve this problem on its own. Under Proposition 13, the county could not raise taxes without approval of two thirds of the voting public.38 Compounding the financial crisis was the growing concern about whether the county public health system had adequate capacity to manage the escalating incidence of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and other dangerous infectious agents.39

The threat of county bankruptcy compelled the Board of Supervisors to consider drastic measures. In 1995, the chief administrative officer, Sally Reed, proposed closing the LAC–USCMC while keeping the other hospitals open. The board ultimately rejected this and similar ideas and instead appointed former assemblyman Burt Margolin as health crisis manager to identify alternative proposals. Margolin negotiated an 1115 Medicaid waiver (a section of the Medicaid law that allows states to propose innovations in health care coverage and delivery) with the US Health Care Financing Administration, now the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.40

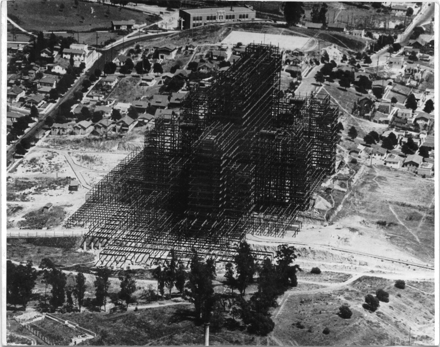

Constructing the Los Angeles General Hospital, circa 1930.

Source. Archives of Robert E. Tranquada, MD.

After weeks of intense negotiations, the waiver approval was announced in Los Angeles on September 22, 1995, by President Bill Clinton, who was running for reelection. The waiver was officially a State Medicaid Demonstration Project, although state contributions to the waiver were zero and the county was fully responsible for implementation. Under the waiver, the county promised a reorientation of its health services emphasis from in-patient to outpatient care. The Board of Supervisors hired a new Department of Health Services director, Mark Finucane, who set a course for a smaller and more integrated system of care. For the first time, the county negotiated contracts with community clinics and physicians for primary care to the uninsured, launched a systemwide reengineering effort, and attempted to renegotiate its professional service agreements with 3 medical schools.

The waiver was considered by some to be a bailout, as it was a transfer of nearly $1 billion over 5 years to the county to prevent a massive meltdown of the system. Yet many of the promised reforms were not realized.41 Nor did it stop the decline in the number of Medi-Cal patients in the Los Angeles County hospitals. Between 1990 and 2000, Medi-Cal admissions in Los Angeles County hospitals dropped from 69% to 54%, while uninsured admissions increased from 21% to 32%.42 Moreover, it did not prevent future deficits or the continuing need for federal intervention.43

In 2000, the county appealed to the federal government for a waiver renewal. This time negotiations were tougher because there was no presidential election campaign. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services reluctantly approved the renewal, albeit with declining federal participation and a new but small role for the state.44 The extension left Los Angeles County once again facing a health system deficit of up to $700 million over 5 years out of an annual operating budget of $2.6 billion. The broader community and the Board of Supervisors again prepared for possible service reductions and facility closures.45 The county considered closing up to 3 hospitals, eliminating some of the gains under the first waiver, and laying off staff. The potential public disaster resulting from these service reductions led to a flurry of activity to try to prevent or at least minimize the impact.46

A new DHS director, Thomas Garthwaite, replaced Finucane in 2002. Garthwaite, a physician, had led the reform of the Veterans Administration health system during the Clinton administration. He developed new reform ideas, advocated for improved disease management and better information systems, and helped expand children’s health insurance. He considered previously proposed ideas for establishing an independent health authority to manage the entire county health system.47 He negotiated with the federal government to reconfigure the terms and conditions of the second, or renewed, federal waiver. This time the county went to the table armed with $165 million from a special property tax assessment for supporting public and private emergency rooms and trauma centers.48 As a way to show good faith that the county was serious about reform, the Board of Supervisors closed 12 clinics and shut down inpatient services at High Desert Hospital. They later voted to close Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Medical Center, but this decision was reversed by court action. Los Angeles County was now dealing with the George W. Bush administration, which many feared would be less supportive of the county’s plan. However, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services agreed to a restructuring of the waiver and to provide an additional $250 million over 2 years.49 Although these funds did not reverse the previous rounds of cuts, once again catastrophe was averted. But Garthwaite’s plan for system reform was interrupted by another crisis in which nearly daily exposés in the Los Angeles Times alleged corruption and poor quality of health care at the Martin Luther King Jr Medical Center.50

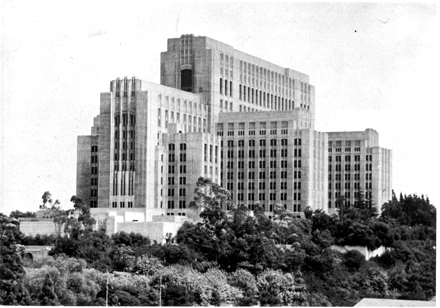

The Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center, circa 1950.

Reproduced with permission of the University of Southern California Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections, Doheny Memorial Library.

It seems ironic that during a course marked by a relentless series of budget crises, policy changes, and allegations of corruption and poor quality, Los Angeles County embarked on a parallel course for building a new hospital. Replacement plans dated back to the 1960s, and more than 100 separate ideas had been studied, but none were implemented. An opportunity arose in 1996 when funds became available from the Federal Emergency Management Agency after the LAC–USCMC was heavily damaged by the 1994 Northridge earthquake. But disagreement over the size of the hospital sharply divided the Board of Supervisors. The DHS, along with many advocacy and provider groups, proposed a 750-bed facility that would be an optimal size to accommodate trauma patients and have enough capacity to serve Medi-Cal patients, who could help pay for the cost of the uninsured.51 Culminating in one of the board’s most dramatic meetings, the supervisors approved a much smaller 600-bed facility, along with a promise to consider a 150-bed inpatient facility in east Los Angeles. Construction of the new LAC–USCMC began in 1998; it is scheduled to open in 2007.

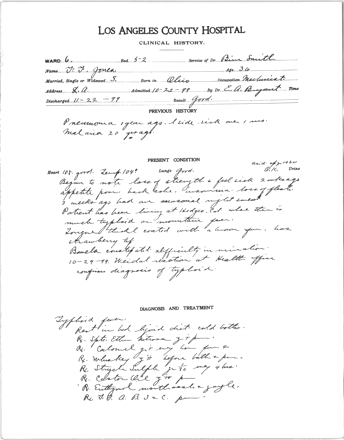

Chart for a Los Angeles County Hospital patient diagnosed with typhoid fever, circa 1899.

Source. Archives of Robert E. Tranquada, MD.

CONCLUSION

The Los Angeles County story demonstrates the ongoing vulnerability of the health care safety net in the United States.52 It shows how a county struggled almost from the beginning with financial and political crises that threatened the viability and survival of its health care system. Each time, Los Angeles County overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles to keep its system afloat. Indigent medical care was increasingly seen as part of the county’s broader public health mission rather than part of its welfare responsibility to the poor. In addition, the financing of medical care in Los Angeles County’s public hospitals evolved from a largely county-financed system of care to one with significant participation from the state and federal governments. These changes occurred in response to social and demographic changes, civil unrest, earthquakes, and health policy changes, particularly following the passage of Medicare, Medicaid, and the state’s Proposition 13.

The new replacement LAC–USCMC will indeed be a modern and state-of-the-art facility designed to meet the state’s highest standards for seismic safety. Yet it is being built on a fragile financial base, reflecting the failures of state and federal policy to stabilize the public hospital system. Moreover, the new county hospital will be at the forefront in addressing some of the community’s most formidable public health challenges: population increases, homelessness, the erosion of employment-based health insurance coverage, a stubbornly persistent AIDS epidemic, an aging population, and increases in chronic disease, all while preparing for natural disasters and the threat of bioterrorism.53 To better plan for these challenges, the County of Los Angeles has once again separated public health services administratively from the hospital and clinic system. However, the hospital’s and indeed the entire DHS’s success in meeting these challenges will depend on whether government leaders at all levels can bring about the reforms needed to stabilize the health care system and assist the County of Los Angeles in achieving its public health mission.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the life of Helen E. Martin, a professor of medicine, the 40-year stalwart director of the diabetes service at the Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center and author of its definitive history, heavily quoted here. She died 6 days after her 100th birthday and during the development of this article. We also acknowledge the assistance of Gregory Stevens, Phinney Ahn, Kyoko Rice, Erin Cox, and Alexi Saldamando. Thanks also to the staff of the University of Southern California Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections, Doheny Memorial Library, for their assistance in making available archival documents and photographs.

Human Subjects No human subjects were involved in this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M.R. Cousineau originated the project, collected and reviewed archival documents and other information, coordinated all revisions, and collected all supporting documents and citations listed in the references. R.E. Tranquada contributed information on the early history of the hospital and helped obtain historical photos. Both authors wrote the article.

References

- 1.The LAC–USCMC is licensed for 1395 beds, although budgeted to staff about half that many. State of California, Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, http://www.osphd.cahwnet.gov (accessed April 1, 2006).

- 2.Diamant Allison, Patient Assessment Survey III, Final Report (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, 2005).

- 3.Apuzzo M., et al., “The General Hospital: Cathedra and Crucible,” Neurosurgery 56 (2005): 1162–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronson Barbara, 120 Years of Medicine: Los Angeles County 1871–1991 (Houston: Pioneer, 1991).

- 5.Opdycke Sandra, No One Turned Away: The Role of Public Hospitals in New York City Since 1900 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Harry Dowling, City Hospitals, The Undercare of the Underprivileged. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1982).

- 6.State of California, California Welfare and Institutions Code, §17000, states, “Every county and every city shall relieve and support all incompetent poor, indigent persons, and the incapacitated by age, disease or accident, lawfully resident therein, when such persons are not supported and relieved by their relatives and friends, by their own means or by state hospitals or other states or private institutions.”

- 7.Institute for the Future, The History of California’s Health Care, The Evolution of the Health Safety Net and the Rise of Managed Care (1997).

- 8.Martin Helen Eastman, The History of Los Angeles County Hospital, 1878–1968; and the Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center 1969–1978. (Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press, 1979) 5–7.

- 9.Ibid., 517.

- 10.Baur John. The Health Seekers of Southern California 1870–1900 (San Marino, Calif: Huntington Library, 1959).

- 11.Abel Emily, “‘Only the Best Class of Immigration’: Public Health Policy Toward Mexicans and Filipinos in Los Angeles, 1910–1940.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (2004): 932–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deverell William, “Plague in Los Angeles, 1924: Ethnicity and Typicality,” in Over the Edge: Remapping the American West, ed. Valerie Matsumoto, 172–200 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

- 13.Rasmussen Cecelia, “In 1924 Los Angeles, a Scourge From the Middle Ages,” LA Then and Now, Los Angeles Times, sec B2, March 5, 2006.

- 14.Molina Natalia, Fit to be Citizens: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles 1879–1939. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

- 15.John L. Pomeroy, “The Public Health Center,” California and Western Medicine, 35, no. 3 (1931): 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shonick William, Government and Health Services: Government’s Role in the Development of U.S. Health Services, 1930–1980 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- 17.Martin Helen Eastman, The History of Los Angeles County Hospital, 1878–1968; and the Los Angeles County University of Southern California Medical Center 1969–1978. (Los Angeles, University of Southern California Press, 1979) 112.

- 18.Commission McCone, Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning? A Report by the Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots (Sacramento: State of California, 1965).

- 19.Harmon Michael Mont, “The Consolidation of the Los Angeles City and County Health Departments: A Case Study” (dissertation, University of Southern California, 1968).

- 20.Robert E. Tranquada, “The Rationalization of Public Medical and Hospital Services in Los Angeles County—A Beginning” (10th IBM Medical Symposium, Poughkeepsie, NY, 1970).

- 21.Martin, History, 267.

- 22.Reidy-Kelch Debra, “Caring for Medically Indigent Adults in California: A History” (paper prepared for the California Health Care Foundation, 2005, 11–17).

- 23.Glassman P., et al, “The 1966 Enactment of Medicare: Its Effect on Discharges from Los Angels County-Operated Hospitals,” American Journal of Public Health 84 (1994): 1325–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.History of County Health Funding Leading up to the 1991 Realignment (Sacramento: County Health Executives Association of California, 1997).

- 25.Schwartz Joel, “Strategies for Monitoring the Effects of Proposition 13 on Health Services,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 4 (1979): 142–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blake Elinor and Thomas Bodenheimer, “Closing the Doors on the Poor: The Dismantling of California’s Public Hospitals.” Health Policy Advisory Center Report 16 (1975): 230. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legneni Mark, et al., Privatization of Public Hospitals, prepared for the Kaiser Family Foundation (Washington: Economic and Social Research Institute, 1999).

- 28.State funds were transferred to the counties under AB 8, which California adopted in 1979 to alleviate the financial crises brought about by Proposition 13.

- 29.Brown E. Richard and Michael R. Cousineau, “Assuring Access to County Health Services: An Assessment of the Beilenson Act, SB 154 and AB 8” (California Policy Seminar, Institute of Governmental Studies, May 1983).

- 30.“The 1991–92 State and Local; Program Realignment: Overview and Current Issues,” in Perspectives and Issues (Sacramento: California Office of the Legislative Analyst, 1992).

- 31.Lurie Nicole, et al., “Termination From Medi-Cal: Does It Affect Health?” New England Journal of Medicine 311 (1984): 480–84. Lurie, et al., “Termination of Medi-Cal Benefits: A Follow up Study one Year Later” New England Journal of Medicine 314 (1984): 1266–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King Peter H, “Care Amid Chaos at County-USC,” Los Angeles Times, sec. 1, January 27, 1985.

- 33.Task Force for Health Care Access in Los Angeles County, Closing the Gap: Report to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, 1992.

- 34.The History of California’s Health Care, The Evolution of the Health Safety Net and the Rise of Managed Care (San Francisco: Institute for the Future, 1997). LA Care is a partnership of several health plans in Los Angeles, including the county-owned and -operated Community Health Plan.

- 35.Los Angeles County has its own HMO, called the Community Health Plan, which also became one of several plan partners operating within the Los Angeles County local initiative called LA Care Health Plan.

- 36.Huen William, California’s Disproportionate Share Hospital Program: Background Paper (San Francisco: California Policy Institute, 1999).

- 37.Wasserman J., et al., Financing the Health Services Safety Net in Los Angeles County (Santa Monica, Calif: Rand Corp, 2004), 32.

- 38.State and county governments are restricted by Proposition 13 from raising taxes without a two-thirds vote of the legislature or of the people through the initiative process.

- 39.Laurie Garrett B etrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health (New York: Hyperion, 2000).

- 40.Under Section §1115 of the Social Security Act, the federal government can waive certain statutory and regulatory Medicaid provisions that enable states to implement special projects and demonstrations. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and Uninsured, The Medicaid Resource Book (Menlo Park, Calif: Menlo Park Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002), 61.

- 41.Zuckerman Steven and Amy Westphahl-Lutzky, Medicaid Demonstration Project in Los Angeles County, 1995–2000: Progress But Room for Improvement, report to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2001).

- 42.Garthwaite Thomas, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, testimony before the select committee on the Los Angeles County Health Care System, Mark Ridley-Thomas, chair (2005).

- 43.Howle Elaine, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services: Despite Securing Additional Funding and Implementing Some Cost-Cutting Measures, It Still Faces Significant Challenges to Addressing its Growing Budget Deficit (Sacramento: State of California, Office of the Auditor, Bureau of State Audits, 2003).

- 44.State of California, Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Project for Los Angeles County: Special Terms and Conditions, extension July 1, 2000, to June 30, 2005, 11-W-00076/9 (Sacramento: California Department of Health Services, 1999).

- 45.County of Los Angeles Department of Health Services, DHS Five-Year Implementation Plan (Los Angeles County: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, 2000).

- 46.County of Los Angeles, Department of Health Services, “System Redesign” (presented to the Board of Supervisors, Health Department Budget Committee of the Whole, June 26, 2002).

- 47.Cousineau Michael, Robert Tran-quada, and Elizabeth Graddy, An Analysis of Alternative Governance for the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (Los Angeles: University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Community Health, May 2003).

- 48.In 2002, more than two thirds of county voters approved Measure B, which allowed the county to raise property taxes. These funds supported emergency rooms and trauma centers only and provided financial support to county and private emergency rooms.

- 49.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Special Terms and Conditions, Waiver No. 11–2-00193/9,” (letter from Marc McClellen, CMS administrator, to S. Kimberly Belshe’, secretary, California Health and Welfare Agency, August 31, 2005).

- 50.A compilation of documents on the Los Angeles County Martin Luther King Jr Medical Center crisis can be found at LA Health Action, http://lahealthaction.org/index.php/library/category_page_featured/C43.

- 51.Robert E. Tranquada and Henry Zaretsky, County of Los Angeles Health Facilities Improvement and Replacement Plan. Final Report to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (Los Angeles County: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, 1996).

- 52.Institute of Medicine, America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered (Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2000). [PubMed]

- 53.Tranquada R., et al., Sick System, A Ten Year Look at the Los Angeles County Health Care System and its Current State of Health, LA Health Action (Los Angeles: California Endowment, 2005).