Abstract

Alcadeinα (Alcα) is an evolutionarily conserved type I membrane protein expressed in neurons. We show here that Alcα strongly associates with kinesin light chain (KD≈4–8 × 10−9 M) through a novel tryptophan- and aspartic acid-containing sequence. Alcα can induce kinesin-1 association with vesicles and functions as a novel cargo in axonal anterograde transport. JNK-interacting protein 1 (JIP1), an adaptor protein for kinesin-1, perturbs the transport of Alcα, and the kinesin-1 motor complex dissociates from Alcα-containing vesicles in a JIP1 concentration-dependent manner. Alcα-containing vesicles were transported with a velocity different from that of amyloid β-protein precursor (APP)-containing vesicles, which are transported by the same kinesin-1 motor. Alcα- and APP-containing vesicles comprised mostly separate populations in axons in vivo. Interactions of Alcα with kinesin-1 blocked transport of APP-containing vesicles and increased β-amyloid generation. Inappropriate interactions of Alc- and APP-containing vesicles with kinesin-1 may promote aberrant APP metabolism in Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Alcadein, Alzheimer's disease, APP, axonal transport, kinesin

Introduction

Conventional kinesin (kinesin-1) is composed of two heavy (KHC) and two light (KLC) chains (Hirokawa, 1998). The N-terminal half of KLC interacts with KHC, and the C-terminus of KLC links to membrane cargo either directly or via cytosolic adaptor proteins such as the JNK-interacting protein 1 (JIP1) (Gauger and Goldstein, 1993; Gindhart and Goldstein, 1996; Verhey et al, 2001). The combinations of cargoes, adaptor proteins, and motor molecules contribute to the diversity of vesicular transport systems (Hirokawa, 1998), the dysfunction of which may underlie some neurodegenerative disorders (Guzik and Goldstein, 2004) such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Stokin et al, 2005).

Amyloid β-protein precursor (APP) has been implicated in the development and progression of AD (Gandy, 2005) and is proposed to be a kinesin-1 cargo. APP can bind to kinesin-1 directly (Kamal et al, 2000; Gunawardena and Goldstein, 2001) or through JIP1 (Inomata et al, 2003; Matsuda et al, 2003). Although the cargo hypothesis has been challenged (Lazarov et al, 2005) and it is unclear how APP functions mechanistically in vesicle transport, disruption of APP-containing vesicle transport may alter APP metabolism, thereby increasing levels of neurotoxic β-amyloid (Aβ) (Gunawardena and Goldstein, 2001; Stokin et al, 2005).

Alcadein (Alc) is an evolutionarily conserved type I membrane protein, which has four isoforms, Alcα1, Alcα2, Alcβ, and Alcγ, in mammals (Araki et al, 2003). These proteins were isolated independently as postsynaptic Ca2+-binding proteins called the calsyntenins (Vogt et al, 2001). Alc associates with APP in neurons through cytoplasmic interactions of both proteins with X11-like (X11L) (Araki et al, 2003), a neuron-specific adaptor protein (Tomita et al, 1999). Formation of a tripartite APP/X11L/Alc complex stabilizes both APP and Alc proteins metabolically. Dissociation of X11L from the complex induces coordinated cleavages of APP and Alc, generating the Aβ fragment from APP and the β-Alc peptide from Alc, in addition to the release of their respective cytoplasmic-domain fragments, AICD and AlcICD (Araki et al, 2004). Thus, Alc may be similar to APP in function as well as metabolism.

Here, we present evidence that Alc is a kinesin-1 cargo and exhibits novel functions. The transport of Alc-containing vesicles competes with that of APP-containing vesicles for kinesin-1, and disruption of transport of APP-containing vesicles increases Aβ generation. This analysis contributes to our understanding of both the pathogenesis of AD and the physiological function of Alc.

Results

Direct interaction of Alc with KLC

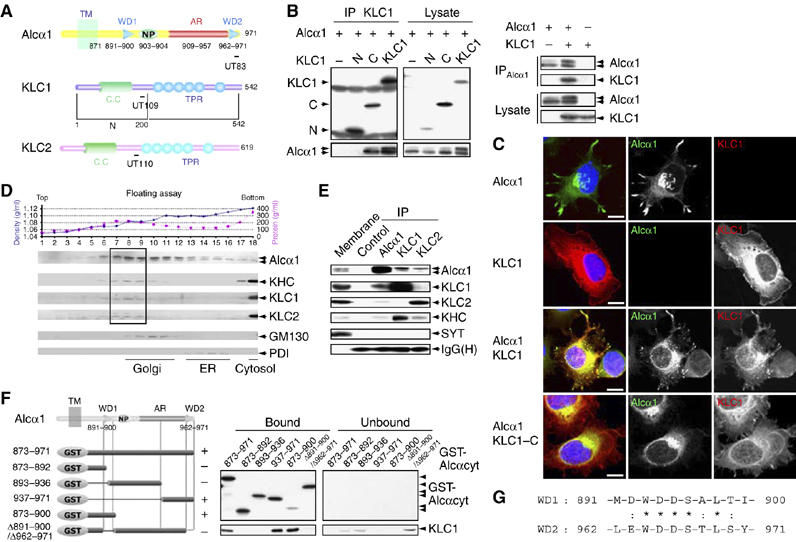

A yeast two-hybrid screen using the cytoplasmic domain of Alcα (amino acids 872–969 of mouse Alcα1) as bait isolated 11 full-length and partial cDNA clones encoding KLC1 (see Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure S1 for the schematic structures of KLC1 encoded by the isolated cDNA clones; Supplementary data is shown in Sup_1.pdf.) and one partial cDNA clone encoding KLC2. The interaction between Alcα1 and KLC1 was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation in HEK293 cells overexpressing Alcα1 and KLC1 (Figure 1A and B, right). Immunoprecipitates obtained with an anti-Alcα antibody contained KLC1, indicating that Alcα interacts with KLC1. To identify the Alcα-binding domain, FLAG-tagged amino- (KLC1-N or N) and carboxy- (KLC1-C or C) terminal halves of KLC1 (Figure 1A) were overexpressed. An anti-FLAG antibody co-immunoprecipitated Alcα1 with KLC1 and with KLC1-C, but not with KLC1-N (Figure 1B, left). These data indicate that Alcα interacts with the KLC1 carboxy-terminus, which includes the tetratrico-peptide repeat (TPR; see Figure 1A), with which other KLC-binding proteins interact (Gindhart and Goldstein, 1996). Alcα1 was also co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-KLC2 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Interaction of Alcα with KLC and determination of the KLC-binding site on Alcα. (A) Structure of the cytoplasmic domains of Alcα, KLC1, KLC1-N (N), KLC1-C (C), and KLC2. Numbers represent amino-acid sequences. TM, transmembrane domain; WD, tryptophan- and aspartic acid-containing sequence (see ‘G'); NP, Asn-Pro motif; AR, acidic region; CC, coiled-coil domain; TPR, tetratrico-peptide repeat. Epitopes for the UT83, UT109, and UT110 antibodies are indicated with bars. (B) (Left panel) Co-immunoprecipitation of Alcα1 with amino-terminal FLAG-tagged KLC1 and deletion constructs. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with pcDNA3-hAlcα1 and pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1 (KLC1), pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1-N (N), pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1-C (C), or pcDNA3.1-FLAG (−). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG (M2) antibody. The immunoprecipitates (IP) and lysate were analyzed by Western blotting with M2 and UT83. (Right panel) Co-immunoprecipitation of KLC1 with Alcα1. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3-hAlcα1 and pcDNA3.1-mKLC1. Transfection with plasmid (+) or vector alone (−) is indicated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Alcα (UT83) antibody. The immunoprecipitates (IP) and lysate were analyzed by Western blotting with UT83 and UT109. (C) Localization of Alcα1 and KLC1. CAD cells were transiently cotransfected with the indicated combinations of pcDNA3-hAlcα1, pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1, and pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1-C for 48 h and differentiated for 24 h by depleting serum. Alcα1 and FLAG-tagged KLC1 were immunostained with UT83 (green) and M2 (red) antibodies, respectively. Nuclei were stained using 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, blue). Merged signals are shown at the left. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Membrane fractionation of brain tissues. The post-nuclear supernatant of adult mouse brains was fractionated by 0–28% iodixanol density gradient centrifugation (Araki et al, 2003). (Upper panel) The density (blue circles) and protein concentration (pink squares) are indicated. Fraction numbers are indicated along the abscissa. (Lower panel) The fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to Alcα (UT83), KHC (H2), KLC1 (UT109), KLC2 (UT110), and the Golgi-resident GM130 (clone no. 35) and the ER-resident PDI (1D3). The dotted square indicates the fractions containing the highest levels of Alcα, KHC, KLC1, and KLC2. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of Alcα with KLC. The mouse brain membrane fraction (500 μg protein) was solubilized, and Alcα1, KLC1, and KLC2 were immunoprecipitated with the UT83, UT109, and UT110 antibodies, respectively, or a control non-immune antibody. The membrane fraction (Membrane, 10 μg protein) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for Alcα (UT83), KLC1 (UT109), KLC2 (UT110), KHC (H2), and SYT (clone no. 41). IgG(H) indicates the IgG heavy chain (rabbit). (F) Determination of the KLC-binding site on Alcα. (Left) Various GST-fusion proteins of the Alcα cytoplasmic domain (shown schematically, numbers are amino-acid residues) were incubated with HEK293 cell lysates expressing FLAG-KLC1. FLAG-KLC1 bound to GST-Alcαcyt was recovered using glutathione beads. (Right) The bound and unbound FLAG-KLC1 were analyzed by Western blotting with the M2 antibody. GST-Alcα1 protein constructs were detected by Western blotting with an anti-GST antibody. In the left panel, ‘+' indicates positive binding and ‘−' indicates negative binding. (G) Amino-acid sequences of WD1 and WD2 of Alcα1. Numbers indicate amino-acid residues. Identical (*) and similar (:) amino-acid residues are indicated.

Alcα1 appears as two bands on SDS–PAGE gels. The more slowly migrating band increased in intensity in the presence of KLC1 and had a mobility similar to that of brain Alcα (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S2). HEK293 cells express substantial amounts of endogenous KHC and KLC2 but lower levels of endogenous KLC1 (Supplementary Figure S2A), as do undifferentiated CAD cells (data not shown), suggesting that the expression of exogenous KLC1 may increase the formation of functional kinesin-1 in both cell types because increased number of transporting Alcα vesicles were observed (data not shown for HEK293 cells and Figure 1C for CAD cells). We determined that Alcα1 was post-translationally modified with both high-mannose (arrow 2) and complex (arrow 1) N-glycans (Supplementary Figure S2B). The predominance of the slow-migrating Alcα1 increased in the presence of KLC1 but not KLC1-C (Figure 1B, left), which does not bind to KHC (Gauger and Goldstein, 1993), suggesting that trafficking of Alcα-containing vesicles by kinesin-1 facilitates complex N-glycosylation.

Alcα colocalized with KLC1 in CAD cells (Figure 1C). CAD cells overexpressing Alcα1 in the presence (Figure 1C, third rows) or absence (first rows) of KLC overexpression began to extend processes that were not observed in cells not expressing Alcα1 (second rows) after serum depletion. Alcα1 protein localized to neurite tips, as well as the ER and Golgi (third rows), whereas FLAG-KLC1 was located in the cytoplasm (second rows). A few small vesicles were observed in cells expressing Alcα1 alone (first rows), but a large number of small vesicles appeared when Alcα1 was coexpressed with FLAG-KLC1, and the proteins were colocalized (third rows), suggesting that Alcα binds the active kinesin-1 motor complex and uses it to transport vesicles to neurite tips. Such vesicles were not observed in cells coexpressing KLC1-C with Alcα1 (fourth rows), as KLC1-C is not able to bind KHC.

Alcα was included in a protein complex containing KLC and KHC in vivo. Mouse brain membranes were fractionated by iodixanol density gradient centrifugation, and Alcα, KHC, KLC1, KLC2, the Golgi-resident protein GM130, and the ER-resident protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) were detected in these membranes (Figure 1D). The complex N-glycosylated Alcα was recovered with kinesin-1 subunits from vesicle fractions that were less dense than the Golgi membrane fractions. The faster-migrating high-mannose N-glycosylated Alcα was largely recovered in the ER. The membranes resulted by 100 000 g centrifugation were solubilized, immunoprecipitated with anti-Alcα, anti-KLC1, anti-KLC2, or nonimmune control antibodies, and subjected to Western blot analysis (Figure 1E). Alcα, KLC1, KLC2, and KHC were immunoprecipitated by anti-Alcα, anti-KLC1, as well as the anti-KLC2 antibody. As a control, synaptotagmin (SYT) was not co-immunoprecipitated by any of the antibodies. These results suggest that Alcα associates with kinesin-1 in vivo.

A pull-down assay with recombinant KLC1 and a GST-Alcα cytoplasmic domain fusion protein (GST-Alcαcyt) demonstrated a direct interaction between KLC1 and Alcα (Supplementary Figure S3A). KLC1 bound to GST-Alcαcyt with a dissociation constant (KD) of ≈7.9 × 10−9 M. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis also demonstrated a strong affinity (KD≈4.3 × 10−9 M) between GST-Alcαcyt and KLC1: the interaction had an association rate (Kass) of approximately 1.3 × 103 M/s and a dissociation rate (Kdiss) of approximately 5.5 × 10−6 M/s (Supplementary Figure S3B). This low dissociation rate indicates a very strong binding between Alcα and KLC1.

The region of Alcα that binds KLC1 was determined by a pull-down assay with glutathione beads bearing GST fusion proteins (Figure 1F). KLC bound to the Alcα fusion protein containing amino acids 873–971, but did not bind to fusion proteins lacking both WD motifs, WD1=amino acids 891–900 and WD2=amino acids 962–971. Each WD motif contains the consensus, D/E-W-D-D-S-A/T-L-T/S (Figure 1G). Deletion of either WD1 or WD2 preserved KLC1 binding, indicating that one WD motif is sufficient for KLC binding. KLC binding to the WD motifs was completely abolished when Ala was substituted for the conserved amino-acid residues in the WD motifs (unpublished observations and Figure 6A), demonstrating a highly specific interaction between Alcα and KLC. These findings in vitro strongly suggest that Alcα1 can function as a kinesin-1 cargo.

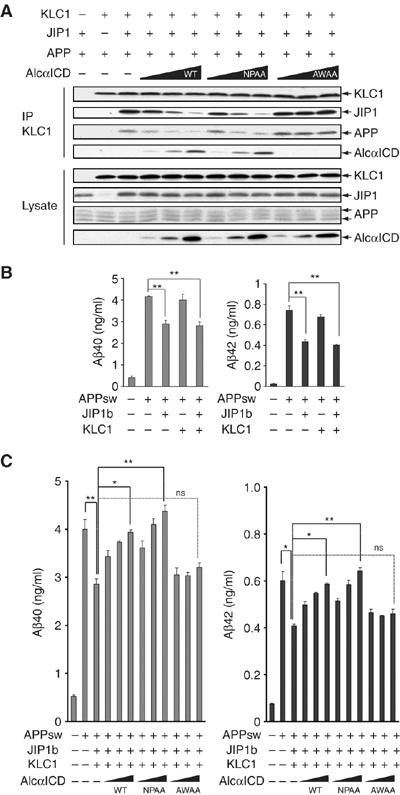

Figure 6.

Increased Aβ production by suppressed transport of APP-containing vesicles. (A) AlcαICD expression interfers with JIP1b-mediated association of APP and KLC1. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-mKLC1, pcDNA3-JIP1b, pcDNA3-hAPP695, and 0, 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 μg pcDNA3-hAlcαICD (WT), pcDNA3-hAlcαICD/NPAA (NPAA), or pcDNA3-hAlcαICD/AWAA (AWAA). Transfection with 0.5 μg plasmid (+) and vector alone (−) is indicated. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-KLC1 antibody (UT109), and the immunoprecipitates (IP) and cell lysates (Lysate, 10 μg protein) were analyzed by Western blotting with UT109, anti-JIP1b (UT72), anti-APP (αAPP/c; Sigma), and anti-Alcα (UT83) antibodies. (B) Aβ secretion from APPsw mutant HEK293 cells expressing JIP1b or KLC1 alone. Aβ secretion from HEK293 cells used in (A) in which transfection of pcDNA3-hAPP695sw was substituted for pcDNA3-hAPP695. At 48 h after transfection, the culture medium was collected and analyzed for Aβ40 (left) and Aβ42 (right) levels using a sandwich ELISA (Araki et al, 2003). Concentrations of Aβ40 and Aβ42 are presented as means±s.e. (n=3). (C) HEK293 cells transfected with pcDNA3-hAPP695sw and the indicated plasmids, as described in (A), were used for Aβ assay. Aβ40 (left) and Aβ42 (right) were quantified as described above. The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test (*P< 0.05; **P<0.01; ns, not significant).

Alc is a novel cargo for kinesin-1 and can mediate the vesicle association of kinesin-1 motor components

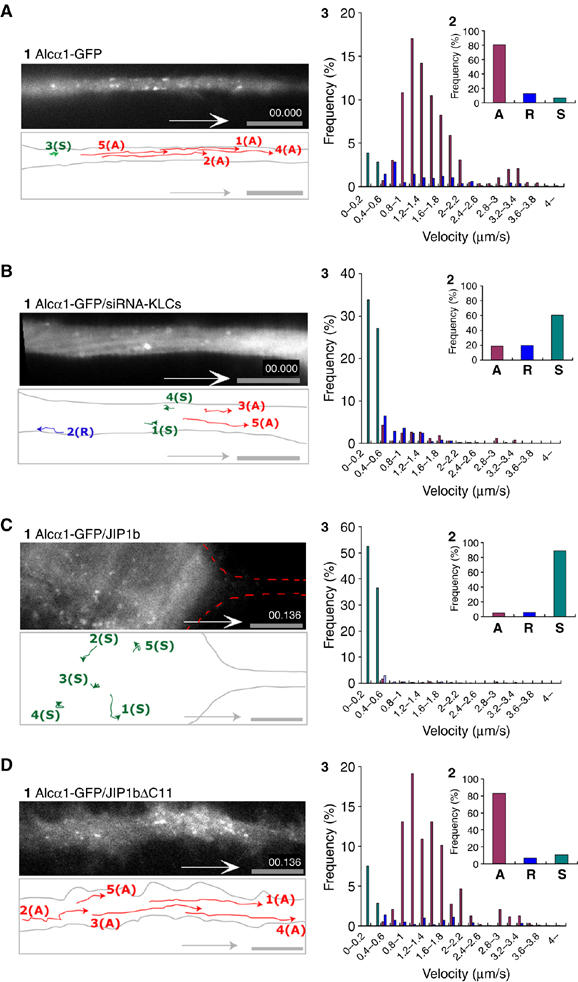

To investigate the characteristics of Alcα1 as a cargo, an Alcα1–GFP fusion protein was expressed in differentiating CAD cells and assayed for vesicular transport. Fast anterograde transport of Alcα1 cargo was observed, together with a minor amount of retrograde movement (Figure 2A, panel 1, and Supplementary Movie 1, part 1 in Sup_2.mov). Approximately 80% of the total Alcα1 cargo vesicles (375 vesicles in 25 cells) showed anterograde transport and 10–15% showed retrograde movement (Figure 2A, panel 2). The anterograde vesicles were transported at a velocity of 1.48±0.45 μm/s (mean±s.d.), which was calculated from the movement of 4125 vesicles (Figure 2A, panel 3) and was consistent with the velocity of 1.32±0.58 μm/s observed in primary cultured mouse cortical neurons expressing Alcα1-Venus (Supplementary Figure S4A and Movie 2, part 1 in Sup_3.mov) and with the velocity of 1.47±0.76 μm/s observed in non-neuronal HEK293 cells expressing Alcα1-Venus and KLC1 (Supplementary Movie 3, part 1 in Sup_4.mov). Alcα1-Venus transport was suppressed by treatment with nocodazole and Alcα1-mRFP-containing vesicles moved on microtubule tracks composed of YFP-tubulin in HEK293 cells (Supplementary Movie 3, parts 2 and 3 in Sup_4.mov). These observations indicate that Alcα is transported on microtubule tracks.

Figure 2.

Kinesin-1-dependent anterograde transport of Alcα cargo in living neuronal cells. (A, B) Anterograde movement of Alcα1 cargo vesicles in an axon. (A) Differentiating CAD cells expressing Alcα1-GFP were observed using TIRF microscopy (panel 1). (B) Kinesin-1-dependent transport of Alcα1 cargo in neuronal cells. Differentiating CAD cells expressing Alcα1-GFP in which KLC1 and KLC2 expression has been knocked down using siRNA were observed using TIRF microscopy (panel 1). Vesicle movements in the dotted square were tracked with time-lapse imaging and are indicated with colored lines and numbers (see Supplementary Movie 1, parts 1 and 2 in Sup_2.mov). Scale bar, 5 μm. (C, D) Inhibition of anterograde transport of Alcα1 cargo by expression of JIP1b. Differentiating CAD cells expressing Alcα1-GFP in the presence of JIP1b (C) and JIP1bΔC11 (D) were observed using TIRF microscopy (panel 1). Vesicle movements in the dotted square were tracked with time-lapse imaging and are indicated with colored lines and numbers (see Supplementary Movie 1, parts 3 and 4 in Sup_2.mov). Scale bar, 5 μm. (A–D) Red lines indicate tracks of anterograde transport, blue lines indicate tracks of retrograde transport, and green spots indicate stationary vesicles moving at less than 0.4 μm/s (panel 1). Alcα1 and APP cargo vesicles transported anterogradely (‘A') and retrogradely (‘R'), and stationary vesicles (‘S') in 25 cells were counted with Metamorph software and the fraction of the total number of vesicles (%) is indicated (panel 2). Distribution (%) of anterograde (red) and retrograde (blue) transport velocity of Alcα1 cargo and of stationary vesicles (green) is shown (panel 3).

To determine whether transport required kinesin-1, endogenous KLC1 and KLC2 expression was knocked down. Differentiating CAD cells expressing siRNA directed against KLC1 or KLC2 showed almost no expression of the respective KLC (data not shown). When siRNA treatment against both KLC1 and KLC2 was performed in differentiating CAD cells, fast anterograde transport of vesicles containing Alcα1-GFP was dramatically inhibited, whereas retrograde transport was largely unaffected (Figure 2B, panel 1, and Supplementary Movie 1, part 2 in Sup_2.mov). Approximately 60% of vesicles (375 vesicles in 25 cells) were stationary (Figure 2B, panels 2 and 3), which is likely to result from interruption of anterograde transport owing to lack of KLC. Identical results were obtained in primary cultured mouse cortical neurons (Supplementary Figure S4B and Movie 2, part 2 in Sup _3.mov).

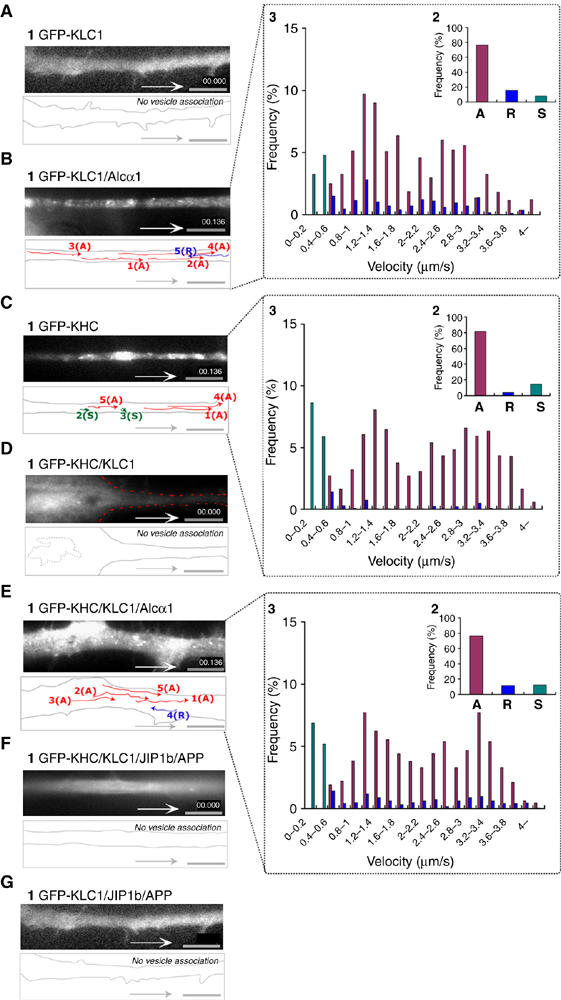

Interestingly, Alcα showed a striking effect on the vesicle association of kinesin-1 motor components. GFP-KLC1 was expressed in differentiating CAD cells in the presence or absence of Alcα1 expression. GFP-KLC alone showed a diffuse distribution, as described previously (Verhey et al, 1998), which also agreed with KLC1 immunostaining (Figure 1C). In contrast, in the presence of Alcα1-, KLC1-containing vesicles were visible and underwent anterograde transport (Figure 3A and B, panels 1 and 2, and Supplementary Movie 4, parts 1 and 2 in Sup _5.mov). The velocity of GFP-KLC1 in anterograde transport was distributed among two populations of vesicles moving at 1.2–1.4 μm/s or ∼3.0 μm/s (Figure 3B, panel 3). These values are consistent with the velocities of Alcα1- and APP cargo-containing vesicles, respectively. Faster moving vesicles at ∼3.0 μm/s may be transported with APP/JIP1b or another cargo following the vesicle association of kinesin-1 component by Alcα1. When GFP-KHC was expressed, vesicles containing GFP-KHC were detected and underwent anterograde transport in the absence of exogenously expressed Alcα1 (Figure 3C and Supplementary Movie 4, part 3 in Sup_5.mov). The velocity of GFP-KHC agreed with that of Alcα1 (∼1.5 μm/s) and APP (∼3 μm/s), indicating that kinesin-1 composed of GFP-KHC and endogenous KLC was associated to membrane via endogenous APP/JIP1b and Alcα1(Figure 3C, panel 3). The vesicle association of GFP-KHC was suppressed by coexpression of unlabeled KLC (Figure 3D and Supplementary Movie 4, part 4 in Sup_5.mov), consistent with the previous observation that overexpression of KLC inhibits binding of KHC to microtubules (Verhey et al, 1998). However, GFP-KHC-containing vesicles were again visible and underwent anterograde transport when Alcα1 was coexpressed in the KLC-overexpressing cells (Figure 3E and Supplementary Movie 4, part 5 in Sup_5. mov). This result cannot be simply due to the quenching and/or masking of overexpressed KLC1 by Alcα1, as overexpression of APP or JIP1b does not cause GFP-KHC to reassociate with vesicles under the same conditions (Figure 3F and Supplementary Movie 4, part 6 in Sup_5.mov). JIP1b and APP did not show any ability to induce vesicle association of GFP-KLC (Figure 3G and Supplementary Movie 4, part 7 in Sup_5.mov). These findings indicate that Alcα modulates the vesicle association of kinesin-1 motor components in axonal cargo transport.

Figure 3.

Vesicle association of kinesin-1 components mediated by Alcα1 cargo in axonal transport. (A, B) Vesicule association of KLC1 induced by Alcα1. Differentiating CAD cells expressing GFP-KLC1 with (B) or without (A) Alcα1 were observed with TIRF microscopy. (C, D) Inhibition of vesicular association of KHC by KLC. Differentiating CAD cells expressing GFP-KHC with (D) or without (C) KLC1 were observed with TIRF microscopy. (E, F) Vesicular association of KHC mediated by Alcα1 (E) but not by JIP1b and APP (F) in the presence of KLC1. (G) KLC is not vesicle associated in the presence of JIP1b and APP. (A–G) Vesicle movements were tracked with time-lapse imaging and are indicated with colored lines and numbers (panel 1; see Supplementary Movie 4, in Sup_5.mov). Red lines indicate tracks of anterograde vesicle transport, blue lines indicate tracks of retrograde vesicle transport, and green spots indicate stationary vesicles moving at less than 0.4 μm/s. Scale bar, 5 μm. Vesicles containing KLC or KHC transported anterogradely (‘A') and retrogradely (‘R'), and stationary vesicles (‘S') in 25 cells were counted with Metamorph software and the fraction of the total number of vesicles (%) is indicated (panel 2 of B, C, E). Distribution (%) of anterograde (red) and retrograde (blue) transport velocity of Alcα1 cargo, as well as stationary vesicles (green), is indicated (panel 3 of B, C, E).

Alc blocks transport of APP-containing vesicles and JIP1b blocks transport of Alc cargo vesicles

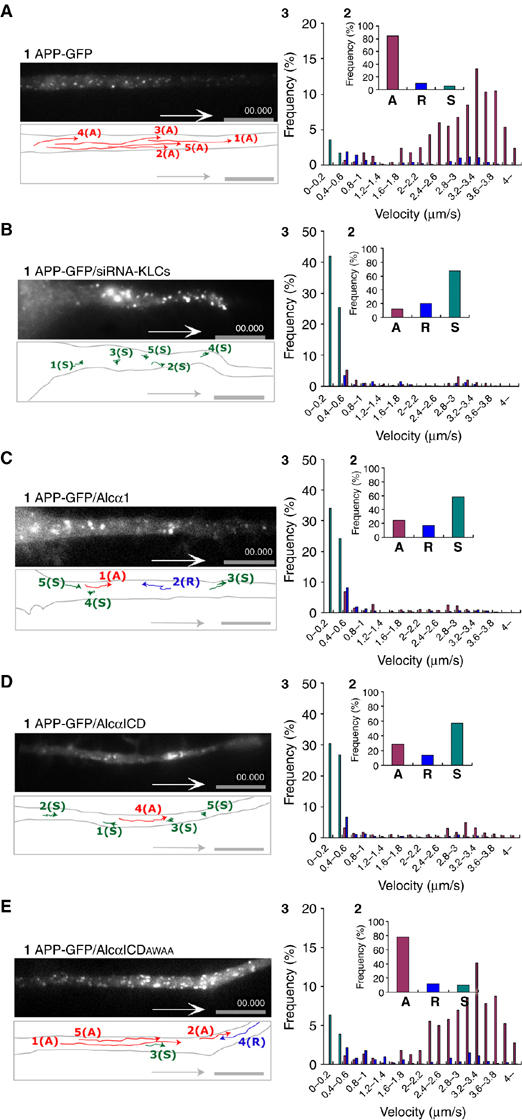

APP is transported by the kinesin-1 motor system (Kaether et al, 2000; Kamal et al, 2000; Gunawardena and Goldstein, 2001). Transport of APP-containing vesicles by kinesin-1 was observed by movement of APP-GFP in differentiating CAD cells (Figure 4A, panel 1, and Supplementary Movie 5, part 1 in Sup_6.mov). The anterograde transport velocity of APP-containing vesicles was extremely fast; most vesicles moved at a speed of 3.0–3.6 μm/s with an average of 3.03±1.07 μm/s (Figure 4A, panel 3). Transport of APP-containing vesicles was suppressed when endogenous KLC1 and KLC2 expression was knocked down (Figure 4B and Supplementary Movie 5, part 2 in Sup_6.mov), suggesting that kinesin-1 transports APP cargoes at a velocity distinct from that of Alcα1 cargoes.

Figure 4.

Transport of APP-containing vesicles and suppression of transport by expression of Alcα1 and AlcαICD in living neuronal cells. (A) Anterograde transport of APP-containing vesicles in an axon. Differentiating CAD cells expressing APP-GFP were observed using TIRF microscopy (panel 1). (B) Kinesin-1-dependent transport of APP-containing vesicles in neuronal cells. Differentiating CAD cells expressing APP-GFP and in which KLC1 and KLC2 expression has been knocked down using siRNA were observed using TIRF microscopy (panel 1). (C–E) Anterograde transport of APP-containing vesicles in differentiating CAD cells expressing APP-GFP in the presence or absence of Alcα1 or AlcαICD. Axonal transport of APP-GFP in the presence of Alcα1 (C), AlcαICD (D), or AlcαICD(AWAA) (E) was observed with TIRF microscopy. Vesicle movements in the dotted square were tracked with time-lapse imaging and are indicated with colored lines and numbers (see Supplementary Movie 5, in Sup_6.mov). Red lines indicate vesicles transported anterogradely (‘A'), blue lines indicate vesicles transported retrogradely (‘R'), and green spots indicate stationary vesicles moving at less than 0.5 μm/s (‘S'). Scale bar, 5 μm. The vesicles in 25 cells were counted with Metamorph software and the fraction of the total number of vesicles (%) is indicated (panel 2). Distribution (%) of anterograde (red) and retrograde (blue) transport velocity of APP-containing vesicles and of stationary vesicles (green) is indicated (panel 3).

Anterograde transport of APP-GFP-containing vesicles was suppressed in the presence of Alcα1 or its cytoplasmic domain fragment AlcαICD, a physiologically produced peptide generated by Alcα1 processing (Araki et al, 2004). However, the mutant AlcαICD (AWAA), in which the KLC-interacting sequence D/E-W-D-D-S within the WD1 and WD2 motifs is altered to A-W-A-A-S making the mutant unable to bind KLC, failed to inhibit the transport of APP-containing vesicles (Figure 4C–E and Supplementary Movie 5, parts 3–5). These observations suggest that APP-containing vesicles are transported in a kinesin-1-dependent manner and that Alcα1 cargo vesicles compete with APP-containing vesicles for kinesin-1.

Conversely, movement of Alcα1 cargo vesicles was suppressed in differentiating CAD cells following expression of JIP1b. Under these conditions, axonal transport of Alcα1 cargo was not observed and vesicles remained in the cell body (Figure 2C and Supplementary Movie 1, part 3 in Sup_2.mov). Expression of JIP1bΔC11, which lacks the KLC-binding site, did not inhibit axonal transport of Alcα1 cargo (Figure 2D and Supplementary Movie 1, part 4 in Sup_2.mov), indicating that the interaction of JIP1b with KLC1 may compete with KLC1 for Alcα1.

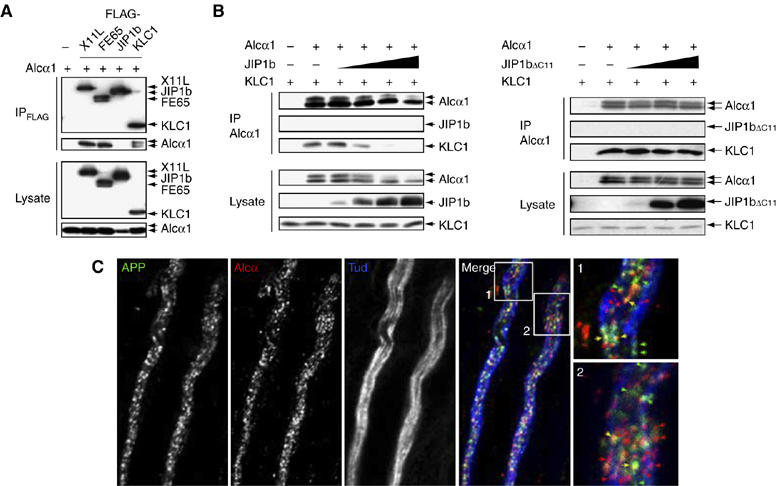

To analyze the role of JIP1b in cargo selection, we first asked whether JIP1b interacts with Alcα1. Alcα1 was coexpressed in HEK293 cells with known FLAG-tagged Alcα-binding proteins (X11L and FE65) (Araki et al, 2003, 2004) or with FLAG-JIP1b and FLAG-KLC1, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Alcα1 co-immunoprecipitated with X11L, FE65, and KLC1, but not JIP1b (Figure 5A). This result indicates that Alcα1 does not associate with KLC via a JIP1b bridge. Lysates of HEK293 cells overexpressing KLC1, Alcα1, and JIP1b were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Alcα antibody. The interaction between Alcα1 and KLC1 was inhibited by JIP1b in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B, left), but not by JIP1bΔC11 (Figure 5B, right). These results indicate that JIP1b binds to KLC1 but not Alcα and suggest that both Alcα and JIP1b share the kinesin-1 motor and that the KLC of kinesin-1 selects an Alcα cargo in the absence of JIP1b.

Figure 5.

Separate transport of APP- and Alcα-containing vesicles by kinesin-1. (A) Interaction of Alcα1 with adaptor proteins. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3-hAlcα1 (+) in the presence of pcDNA3-FLAG-hX11L, pcDNA3-N-FLAG-FE65, pcDNA3-FLAG-JIP1b, pcDNA3.1-FLAG-mKLC1, or vector alone (−). Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Immunoprecipitates (IP) and cell lysates (Lysate) were analyzed by Western blotting with the M2 and anti-Alcα UT83 antibodies. (B) Effect of wild-type and mutant JIP1b on the Alcα1-KLC1 interaction. (Left) HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-mKLC1 (0.5 μg), pcDNA3-hAlcα1 (0.5 μg), and 0, 0.05, 0.2, 0.7, or 2.2 μg pcDNA3-JIP1b. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Alcα (UT83) antibody and immunoprecipitates (IP) and cell lysates (Lysate, 10 μg protein) were analyzed by Western blotting with the UT83, UT72, and UT109 antibodies. (Right) Cells were similarly cotransfected using 0, 0.2, 0.7, or 2.2 μg pcDNA3.1-JIP1bΔC11. The UT83 immunoprecipitate (IP) and cell lysate (Lysate, 10 μg protein) were analyzed as described above. Transfection with 0.5 μg plasmid (+) or vector alone (−) is indicated. (C) APP- and Alcα-containing vesicles in adult mouse sciatic nerve. Isolated axons of sciatic nerves were immunostained with anti-APP (αAPP/C, green), anti-Alcα (co190, red), and anti-neuronal Class III β-tubulin (TUJ1, blue; showing axons) antibodies. Signals are merged and magnified in the lower panels. Yellow arrows indicate vesicles containing both APP and Alcα. Scale bar, 5 μm.

APP-containing vesicles are transported with a velocity different from that of Alcα cargo vesicles (Figures 2 and 4). This is not a result derived from transport inhibition that the transport of one class of vesicle and/or organelle leads to a traffic jam that blocks the movement of other vesicles and/or organelles, because APP-GFP and Alcα1-mRFP are transported in the same cell at different velocities without a trafficking jam in our experimental condition and the transport of both proteins was suppressed in the same cell when the expression of KLCs was knocked down (Supplementary Figure S5 and Movie 6 in Sup_7.mov). However, it needs to be confirmed whether APP-containing vesicles and Alcα cargos are independently transported in vivo. To examine this, we localized endogenous APP- and Alcα-containing vesicles in the sciatic nerve of adult mice (Figure 5C). Most APP (green) and Alcα (red) axonal vesicles were separate, but a few stained for both proteins. We confirmed this in a separate study by staining with the independent synaptic vesicle marker, synaptophysin (Supplementary Figure S6). APP and Alcα were colocalized on almost 30% of the vesicles, whereas both Alcα and APP localized independently of synaptophysin. These results indicate that APP and Alcα are largely transported separately, although a minor population of vesicles may contain both proteins. Alternatively, kinesin-1 may exchange APP-containing vesicles for Alcα cargo vesicles, or vice versa, at the points of colocalization.

Suppressed transport of APP-containing vesicles by Alcα facilitates Aβ generation

A previous report indicated that impaired axonal transport resulting from a reduction in the levels of kinesin-1 increased Aβ levels (Stokin et al, 2005). Therefore, we hypothesized that the relative amounts of JIP1b and Alcα, which facilitate or retard APP transport, respectively, may be important for the regulation of Aβ generation. When Alcα cargoes predominate, the movement of APP-containing vesicles is severely impaired (Figure 4C and Supplementary Movie 5, part 3 in Sup_6.mov). We examined Aβ generation in cells in which APP-containing vesicles are being actively transported by association with kinesin-1 in the presence of JIP1b, or in which transportation of those vesicles is retarded due to overexpression of AlcαICD. AlcαICD was used in the following study instead of Alcα1, as the overexpression of Alcα1 competitively inhibits the cleavage of APP, resulting in an apparent reduction of Aβ generation. AlcαICD directly associates with KLC1 and suppresses the transport of APP as well as Alcα1 (Figure 4D and Supplementary Movie 5, part 4 in Sup_6.mov), but does not compete with APP for cleavage (Supplementary Figure S7).

When KLC1, APP, and JIP1b were overexpressed in HEK293 cells and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-KLC1 antibody, JIP1b and APP co-immunoprecipitated with KLC1, but their recovery was decreased by coexpression of AlcαICD(WT) (Figure 6A). This effect was also observed when the Asn-Pro motif of AlcαICD was altered to Ala-Ala (NPAA), which blocks the ability of Alcα to bind to X11L and FE65 (Araki et al, 2004), but not to KLC (Figure 1F). In contrast, the AlcαICD(AWAA) mutant failed to inhibit KLC1 association with JIP1b, did not attenuate the recovery of JIP1b and APP (Figure 6A), and showed no effect on APP transport (Figure 4E). Finally, overexpression of AlcαICD(WT) in differentiating CAD cells dramatically inhibited anterograde transport of APP-GFP-containing vesicles and resulted in the aggregation of APP-containing vesicles (Figure 4D). These observations suggest that excess AlcαICD attenuated the connection of APP to kinesin-1, causing a defect in APP transport.

Stokin et al (2005) suggested that deficits in axonal transport induce early pathogenesis in AD. Thus, we tested whether APP-containing vesicles actively transported by the kinesin-1 motor could suppress the generation of Aβ40 and Aβ42, compared to those that have stopped moving after dissociation from kinesin-1 in the presence of an excess amount of AlcαICD. To analyze the change in Aβ generation more quantitatively, we used APP Swedish mutant (APPsw) (Citron et al, 1992), which is more susceptible to cleavage to produce greater amount of Aβ than the wild-type APP. The APPsw was transfected into HEK293 cells with or without JIP1b, KLC1, or AlcαICD and the amount of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 was quantified by sELISA. Up to 10-fold greater amounts of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were generated after transfecting APPsw into cells, compared to the level of endogenously generated Aβ (Figure 6B and C). KLC1 expression did not affect the generation of Aβ40 and Aβ42, although JIP1b expression showed a slight decrease in generation of both Aβ species, as reported previously (Taru et al, 2002a). The levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 secreted from APPsw cells decreased ∼25% following expression of JIP1b and KLC1 (Figure 6C), which is consistent with the level of JIP1b expression alone (Figure 6B). This suppression was reversed by coexpression of AlcαICD(WT) or AlcαICD(NPAA); however, AlcαICD(AWAA) coexpression did not block the suppressive effect of JIP1b and KLC1 on Aβ40 and Aβ42 generation. These observations suggest that JIP1b connection of APP to KLC and the resulting kinesin-1-dependent active movement of APP-containing vesicles suppress generation of Aβ40 and Aβ42, and that stationary and/or aggregating states of these vesicles increase Aβ40 and Aβ42 generation. These observations support the previous report by Stokin et al (2005) and suggest a significant role of JIP1b and Alcα in APP transport and Aβ generation.

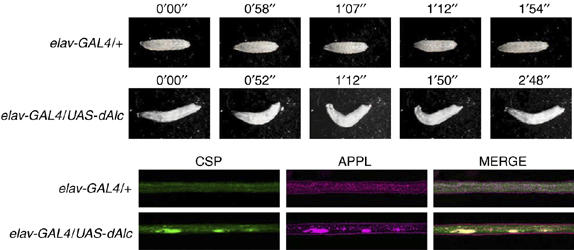

Disruption of axonal transport of APP-like-containing vesicles by dAlc perturbs motor neuron activity

Coordinate sharing of Alcα cargo vesicles and APP-containing vesicles by kinesin-1 may be necessary for normal neuronal function. To analyze these functions, we expressed the Drosophila ortholog of alcadein (dAlc) in flies. UAS-dAlc was expressed in all Drosophila neurons using the pan-neuronal elav-Gal4 driver (Chalvet and Samson, 2002). Third-instar larvae overexpressing dAlc showed locomotor defects, including aberrant tail-flipping movements, rather than normal waves of contraction (Figure 7, upper panels, and Supplementary Movie 7 in Sup_8.mov). These defects were not observed in elav-GAL4/+ larvae not overexpressing dAlc. Immunostaining of larval segmental nerves, which connect to muscles, with an anti-synaptic vesicle-marker protein (CSP) and anti-Drosophila APP-like (APPL) antibodies revealed an accumulation of enlarged and aggregated vesicles in elav-GAL4/UAS-dAlc axons. These enlarged vesicles contained APPL (Figure 7, lower panels) and resemble APP-containing vesicles formed in differentiating CAD cells expressing APP-GFP in the presence of Alcα1 and AlcαICD (Figure 4C and D). The disruption of APPL anterograde transport by overexpression of dAlc may disrupt motor neuron function.

Figure 7.

Impairment of motor neuron function and axonal transport by dAlc expression in Drosophila. (Upper panels) Larval movement. Movement of elav-GAL4/+ (upper) and elav-GAL4/UAS-dAlc (lower) third instar larvae. Numbers indicate time. See Supplementary Movie 7, in Sup_8.mov. (Lower panels) Aggregation of APPL-containing vesicles by dAlc expression. Immunostaining of axons from elav-GAL4/+ (upper) and elav-GAL4/UAS-dAlc (lower) third instar larvae. Larval segmental nerve axons were stained with antibodies against a synaptic vesicle marker protein (CSP) and APPL. Merged signals are shown in the panels on the right.

Discussion

Here, we reported five novel findings relevant to the function of Alcα and APP metabolism. (i) Alcα binds directly to KLC, and Alcα cargoes are transported by kinesin-1 at speeds slower than the transport velocity of APP-containing vesicles, which are also transported by kinesin-1. Thus, the velocity of transport is not solely determined by motor molecules but may be dependent on the combination of motor molecules and cargoes or adaptor proteins. (ii) Alcα can induce vesicle association of the kinesin-1 motor for axonal transport of cargo. The ability to regulate vesicle association of kinesin-1 motor components in the axonal transport of the cargoes is a novel feature of Alcα that has not been observed in other cargo and/or adaptor proteins. (iii) Alcα and JIP1b compete for kinesin-1 binding. (iv) Transport of APP-containing vesicles by kinesin-1 suppresses Aβ generation, while accumulation of stationary or aggregated APP-containing vesicles, potentially resulting from competition for KLC binding by another cargo, causes increased Aβ generation. (v) Disruption of the normal kinesin-1 motor system sharing by cargo or adaptor proteins produces defects in neural function. This is the first identification of Alcα as a novel cargo regulating kinesin-1 function and the first analysis of its association with APP transport and metabolism.

A schematic representation of the activity of Alc as a cargo is shown in Supplementary Figure S8A. Secretory vesicles containing Alcα activate kinesin-1 motor components through interactions with KLC and initiate anterograde transport of cargo. At the appropriate destination, KLC must release the Alcα cargo from the microtubule track and Alcα then appears on the plasma membrane. The slow dissociation of the KLC–Alcα interaction suggests that a covalent modification may be necessary for dissociation. In contrast, kinesin-1 transports APP-containing vesicles via JIP1b (Supplementary Figure S8B). JIP1b may connect KLC to APP or to an unidentified cargo (Supplementary Figure S8B, left panel). Kinesin-1 may release the APP-containing vesicle, replacing it with an Alc cargo vesicle. Alternatively, AlcαICD resulting from Alcα cleavage could compete with JIP1b or an unknown cargo for KLC binding, which would also release APP-containing vesicles (Supplementary Figure S8B, middle panel). Competition for kinesin-1 may promote accumulation of APP-containing vesicles in axons and cell bodies and facilitate Aβ generation (Supplementary Figure S8B, right panel). It is still unclear whether APP-containing vesicles include APP cleaving enzymes such as β-secretase and/or γ-secretase (Kamal et al, 2001; Lazarov et al, 2005). APP-containing vesicles aberrantly released from kinesin-1 may fuse more easily to other vesicles containing APP secretases in the aggregated state or be more easily transported to membrane regions rich in secretases.

It is still unclear whether APP serves as a cargo or not. Kamal et al (2000) reported a direct interaction of APP with KLC (Kamal et al, 2000), whereas our study and other groups have indicated that KLC most likely interacts with APP through JIP1b (Matsuda et al, 2003; Inomata et al, 2003). However, neither of these two conflicting observations prove or disprove the hypothesis that APP is a cargo of kinesin-1. However, a report that included the combined work of several research groups did not support the hypothesis that APP acts as a kinesin-1 cargo (Lazarov et al, 2005). Whatever the outcome of this polemic, our results clearly show that APP is transported by the kinesin-1 motor system and that this transport competes with Alc transport for kinesin-1.

In neurons, APP and Alc form a complex through cytoplasmic interactions with X11L, and both APP and Alc are metabolically stable in the complex (Araki et al, 2003, 2004). However, Alcα transport was largely independent of APP transport. Immunostaining of transporting vesicles in axon indicated that ∼30% of vesicles contained both APP and Alcα and the other ∼70% of vesicles contained either APP or Alcα. One possible interpretation is that APP and Alc are separately transported to nerve terminals, and that vesicles containing either protein are released at their destination and then exposed on the plasma membrane. APP, X11L, and Alc may form a complex either before leaving the Golgi apparatus, at the plasma membrane, or during the endocytotic process. Our preliminary immunostaining observations in differentiating CAD cells suggest that APP, X11L, and Alcα were largely colocalized in the Golgi, whereas APP and X11L did not show any apparent colocalization of vesicles transporting along the axon, although X11L was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm with some accumulation around the Golgi (unpublished observation).

Prominent defects in axonal transport are often observed in neurodegenerative diseases. Disorders in axonal transport are often accompanied by axon terminal enlargement and aberrant accumulation of cargo (Yagishita, 1978). APP and Alc are highly colocalized in dystrophic neurites (Araki et al, 2003), which are enlarged by the accumulation of transported vesicles in the AD brain (Shoji et al, 1990; Cras et al, 1991). Moreover, in a fly model, overexpression of Drosophila APPL results in disruption of axonal transport, suggesting a role for APPL in microtubule-dependent vesicle trafficking (Torroja et al, 1999). Our data support the hypothesis that APP and Alc share the same kinesin-1 motor system for transport and that disruption of axonal transport of APP-containing vesicles can enhance the generation of Aβ, which may be a primary cause of AD pathogenesis (Stokin et al, 2005). Axonal transport well coordinated by the kinesin-1 motor for APP-containing vesicles and Alc cargo vesicles may be required for normal neuronal function as suggested by our observations that neuronal expression of dAlc in flies disrupts axonal transport of APPL-containing vesicles and perturbs motor neuron activity. These studies indicate that a quantitative imbalance in dAlc and APPL, and potentially APLIP1, which is a Drosophila JIP1b ortholog that associates with APPL and kinesin (Taru et al, 2002b; Horiuchi et al, 2005), results in vesicular aggregation and the accompanying deficits in neuronal function. Furthermore, dysfunctions in the exquisitely regulated axonal transport system may disturb formation of a stable tripartite APP, X11L, and Alc complex and result in overproduction of Aβ (Araki et al, 2003). These and future analyses of the molecular mechanisms of transport of APP-containing vesicles and Alc cargo vesicles should shed light on AD pathogenesis as they elucidate cargo-transport mechanisms.

Addendum

During the review process of this manuscript, similar observation on Calsyntenin/Alc binding to kinesin-1 was reported by Konecna et al (2006).

Materials and methods

cDNA cloning and plasmid construction

Mouse KLC1 cDNA encoding 542 amino acids (GenBank accession number AY753300/AK031309) and KLC2 cDNA encoding 619 amino acids (BC014845) were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) at the HindIII/XbaI sites for KLC1 (pcDNA3.1-mKLC1) and the EcoRI/EocRV sites for KLC2 (pcDNA3.1-mKLC2). The KLC1 used in this study has a 98% DNA sequence homology and a 97% protein sequence identity to KLC1A (BK000668). Further information is described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf.

Antibodies

The anti-KLC1 polyclonal rabbit antibody (UT109) was raised against a peptide of mouse KLC1, amino acids 154–171, with an added amino-terminal Cys (C+KKYDDDISPSEDKDSDS), and the anti-KLC2 polyclonal rabbit antibody (UT110) was raised against a peptide of mouse KLC2, amino acids 149–163, with an added N-terminal Cys (C+DASPNEEKGDVPKDS). Further information is described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf.

Total internal reflectance fluorescence microscopy analysis

The cells were observed using a total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy system (C1; Nikon) with a CCD camera (Cascade 650; Photometrics Co.). The transport velocity of vesicles was analyzed with Metamorph 6.1 software (Universal Imaging Co.), and the average values of 10 frames at 667 ms/frame were plotted. Further information is described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf.

In vitro binding assay and SPR analysis

cDNA clones encoding the cytoplasmic domain of human Alcα (amino acids 873–971 of Alcα1) and deletion constructs (Figure 1F, left panel) were subcloned into pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare) to produce the GST-Alcαcyt fusion proteins. In vitro binding assays using GST fusion proteins were performed (Taru et al, 2002b) as described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf. SPR analysis was performed using the Biacore system (Biacore International), as described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot assays

Preparation of cell lysates and brain membrane fractions is described in Supplementary data in Sup_1.pdf. The lysates and their immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using specific antibodies. To accomplish more complete separation of the two Alcα bands, we used a discontinuous separating gel composed of 8% (w/v) and 15% (w/v) polyacrylamide with a standard stacking gel.

siRNA knock down of KLC1 and KLC2

cDNAs of siRNA were designed against the mouse KLC1 (nucleotides 1433–1451, 5′-GTTTGAAGCTGCAGAGACA-3′) and KLC2 (nucleotides 1193–1201, 5′-GGAGTTTGGCTCAGTCAAT-3′) genes and subcloned into the pSuper vector (OligoEngine). Mouse CAD cells and primary cultured neurons were cotransfected with GFP (pcDNA3.1-GFP) and the expression level of endogenous KLC1 and KLC2 was examined by immunostaining of transfected cells expressing GFP with the UT109 and UT110 antibodies.

Immunostaining of CAD cells and mouse peripheral nerves

CAD cells, a mouse CNS catecholaminergic cell line in which morphological differentiation can be initiated by serum depletion (Qi et al, 1997), expressing Alcα1 and FLAG-KLC1 were fixed and stained with the UT83 and M2 antibodies. After the cells were washed, they were further incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or an Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. The cells were viewed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510 META NILO, Carl Zeiss). Immunostaining of mouse peripheral nerves is described in Supplementary data, Sup_1.pdf.

Drosophila study

cDNA encoding dAlc was purchased from Invitrogen (ResGen product) and inserted into pUAST (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) to construct pUAST-dAlc. Germline transformation was carried out as described previously (Robertson et al, 1988). The homozygous UAS-dAlc insertion line or Canton S (wild type) was crossed with the elav-GAL4 line and two independent P-inserted lines were analyzed, both showing identical phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary movie 1

Supplementary movie 2

Supplementary movie 3

Supplementary movie 4

Supplementary movie 5

Supplementary movie 6

Supplementary movie 7

Supplementary Figures and Legends

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs A Miyawaki (RIKEN, BSI), D Chikaraishi (Duke University), S Gandy (Thomas Jefferson University), K Zinsmaier (Caltech), and K White (Princeton University) for supplying materials. We thank Dr H Morioka for assistance with the SPR analysis, the Nikon imaging center for TIRF analysis (Hokkaido University), and Hamamatsu Photonics KK for using ASHURA system. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 16209002 (TS), 18023001 (TS), 18050001 (TS), and 16015333 (TY) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, Sports, and Technology JAPAN and by ‘The 21st Century COE program' for Advanced Life Science on the Base of Bioscience and Nanotechnology (TS and MK). YA is the recipient of research fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for young scientists.

References

- Araki Y, Miyagi N, Kato N, Yoshida T, Wada S, Nishimura M, Komano H, Yamamoto T, De Strooper B, Yamamoto K, Suzuki T (2004) Coordinated metabolism of Alcadein and amyloid β-protein precursor regulates FE65-dependent gene transactivation. J Biol Chem 279: 24343–24354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki Y, Tomita S, Yamaguchi H, Miyagi N, Sumioka A, Kirino Y, Suzuki T (2003) Novel cadherin-related membrane proteins, Alcadeins, enhance the X11-like protein-mediated stabilization of amyloid β-protein precursor metabolism. J Biol Chem 278: 49448–49458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalvet F, Samson M-L (2002) Characterization of fly strains permitting GAL4-directed expression of found in neuron. Genesis 34: 71–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Oltesdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung AY, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe DJ (1992) Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases β-protein production. Nature 360: 672–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cras P, Kawai M, Lowery D, Gonzalez-DeWhitt P, Greenberg B, Perry G (1991) Senile plaque neurites in Alzheimer disease accumulate amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 7552–7556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandy S (2005) The role of cerebral amyloid β accumulation in common forms of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 115: 1121–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauger AK, Goldstein LSB (1993) The Drosophila kinesin light chain. Primary structure and interaction with kinesin heavy chain. J Biol Chem 268: 13657–13666 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gindhart JG, Goldstein LSB (1996) Tetratrico peptide repeats are present in the kinesin light chain. Trends Biochem Sci 21: 52–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena S, Goldstein LSB (2001) Disruption of axonal transport and neuronal viability by amyloid precursor protein mutations in Drosophila. Neuron 32: 389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik BW, Goldstein LSB (2004) Microtubule-dependent transport in neurons: steps towards an understanding of regulation, function and dysfunction. Cur Opin Cell Biol 16: 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N (1998) Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science 279: 519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi D, Barkus RV, Pilling AD, Gassman A, Saxton WM (2005) APLIP1, a kinesin binding JIP-1/JNK scaffold protein, influences the axonal transport of both vesicles and mitochondria in Drosophila. Curr Biol 15: 2137–2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata H, Nakamura Y, Hayakawa A, Tanaka H, Suzuki T, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N (2003) A scaffold protein JIP-1b enhances amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation by JNK and its association with kinesin light chain 1. J Biol Chem 278: 22946–22955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaether C, Skehel P, Dotti CG (2000) Axonal membrane proteins are transported in distinct carriers: a two-color video microscopy study in cultured hippocampal neurons. Mol Biol Cell 11: 1213–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Almenar-Queralt A, LeBlanc JF, Roberts EA, Goldstein LSB (2001) Kinesin-mediated axonal transport containing β-secretase and presenilin-1 requires APP. Nature 414: 643–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Stokin GB, Yang Z, Xia C-H, Goldstein LB (2000) Axonal transport of amyloid precursor protein is mediated by direct binding to the kinesin light chain subunit of kinesin-I. Neuron 28: 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konecna A, Frischknecht R, Kinter J, Ludwig A, Steuble M, Meskenaite V, Indermuhle M, Engel M, Cen C, Mateos JM, Streit P, Sonderegger P (2006) Calsyntenin-1 docks vesicular cargo to kinesin-1. Mol Biol Cell 17: 3651–3663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov O, Morfini GA, Lee EB, Farah MH, Szodorai A, DeBoer SR, Koliatsos VE, Kins S, Lee VM-Y, Wong PC, Price DL, Brady ST, Sisodia SS (2005) Axonal transport, amyloid precursor protein, kinesin-1, and the processing apparatus: revisited. J Neurosci 25: 2386–2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Matsuda Y, D'Adamio L (2003) Amyloid β protein precursor (AβPP), but not AβPP-like protein 2, is bridged to the kinesin light chain by the scaffold protein JNK-interacting protein 1. J Biol Chem 278: 38601–38606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Wang JT, McMillian M, Chikaraishi DM (1997) Characterization of a CNS cell line, CAD, in which morphological differentiation is initiated by serum deprivation. J Neurosci 17: 1217–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HM, Preston CR, Phillis RW, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Benz WK, Engels WR (1988) A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 118: 461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Hirai S, Yamaguchi H, Harigaya Y, Kawarabayashi T (1990) Amyloid β-protein precursor accumulates in dystrophic neuritis of senile plaques in Alzheimer-type dementia. Brain Res 512: 164–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokin GB, Lillo C, Falzone TL, Brusch RG, Rockenstein E, Mount SL, Raman R, Davies P, Masliah E, Williams DS, Goldstein LSB (2005) Axonopathy and transport deficits early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Science 307: 1282–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taru H, Iijima K, Hase M, Kirino Y, Yagi Y, Suzuki T (2002b) Interaction of Alzheimer's β-amyloid precursor family proteins with scaffold proteins of the JNK signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 277: 20070–20078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taru H, Kirino Y, Suzuki T (2002a) Differential roles of JIP scaffold proteins in the modulation of amyloid precursor protein metabolism. J Biol Chem 277: 27567–27574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Ozaki T, Taru H, Oguchi S, Takeda S, Yagi Y, Sakiyama S, Kirino Y, Suzuki T (1999) Interaction of a neuron-specific protein containing PDZ domains with Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem 274: 2243–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja L, Chu H, Kotovsky I, White K (1999) Neuronal overexpression of APPL, the Drosophila homologue of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), disrupts axonal transport. Current Biol 9: 489–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey KJ, Lizotte DL, Abramson T, Barenboim L, Schnapp BL, Rapoport TA (1998) Light chain-dependent regulation of kinesin's interaction with microtubules. J Cell Biol 143: 1053–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey KJ, Meyer D, Deehan R, Blenis J, Schnapp B, Rapoprt T, Margolis B (2001) Cargo of kinesin identified as JIP scaffolding protein and associated signaling molecules. J Cell Biol 152: 959–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt L, Schrimpf SP, Meskenaite V, Frischknecht R, Kinter J, Leone DP, Ziegler U, Sonderegger P (2001) Calsyntenin-1, a proteolytically processed postsynaptic membrane protein with a cytoplasmic calcium-binding domain. Mol Cell Neurosci 17: 151–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagishita S (1978) Morphological investigations on axonal swellings and spheroids in various human disease. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 378: 181–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary movie 1

Supplementary movie 2

Supplementary movie 3

Supplementary movie 4

Supplementary movie 5

Supplementary movie 6

Supplementary movie 7

Supplementary Figures and Legends