Abstract

Background

Higher crash rates per mile driven in older drivers have focused attention on the assessment of older drivers.

Objective

To examine the attitudes and practices of family physicians regarding fitness-to-drive issues in older persons.

Design

Survey questionnaire.

Participants

The questionnaire was sent to 1,000 randomly selected Canadian family physicians. Four hundred sixty eligible physicians returned completed questionnaires.

Measurements

Self-reported attitudes and practices towards driving assessments and the reporting of medically unsafe drivers.

Results

Over 45% of physicians are not confident in assessing driving fitness and do not consider themselves to be the most qualified professionals to do so. The majority (88.6%) feel that they would benefit from further education in this area. About 75% feel that reporting a patient as an unsafe driver places them in a conflict of interest and negatively impacts on the patient and the physician–patient relationship. Nevertheless, most (72.4%) agree that physicians should be legally responsible for reporting unsafe drivers to the licensing authorities. Physicians from provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting requirements are more likely to report unsafe drivers (odds ratio [OR], 2.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.58 to 4.91), but less likely to perform driving assessments (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.85). Most driving assessments take between 10 and 30 minutes, with much variability in the components included.

Conclusions

Family physicians lack confidence in performing driving assessments and note many negative consequences of reporting unsafe drivers. Education about assessing driving fitness and approaches that protect the physician–patient relationship when reporting occurs are needed.

Key words: survey, older drivers, medical fitness to drive, family physicians

INTRODUCTION

Statistics revealing the aging of the population and higher-than-average motor vehicle crash (MVC) rates per mile driven for older drivers have focused attention on the assessment of the fitness of older drivers.1–5 Physicians play a major role in assessing fitness to drive and in reporting unsafe drivers to the authorities.1,6,7 When a physician deems a patient unfit to drive, it can undermine an older person’s sense of independence, contributing to depressive symptoms, social isolation, and a diminished quality of life,8–10 and can strain the physician–patient relationship.11

Legislation regarding a physician’s responsibility to report unsafe drivers varies by province in Canada6 and by state in the United States.12 In British Columbia (BC), physicians are mandated to report an unfit driver only if the driver continues to drive after they have been informed that they are unsafe to do so. In Quebec, Alberta, and Nova Scotia, reporting is discretionary. In all other Canadian provinces/territories, physicians are required to report to the licensing authorities all patients who, in their opinion, may be medically unfit to drive. Failure to report has resulted in physicians being found partially liable for MVCs in several civil suits, both in Canada and the United States.12–15

The Canadian Medical Association publishes a handbook titled Determining Medical Fitness to Drive: A Guide For Physicians.6 The handbook is organized into different sections corresponding to conditions that can affect driving (e.g., nervous system diseases, cardiovascular diseases, the aging driver). However, the guide does not outline a standard set of areas that should be assessed, and the recommendations are mainly empirical.

In Canada, primary care is provided predominantly by family physicians. No prior study has examined the attitudes and practices of Canadian family physicians regarding the assessment of fitness to drive and the reporting of unsafe older drivers. We conducted a national survey to obtain this information.

METHODS

We carried out a cross-sectional mailed survey in August and September of 2003. The intended population under study was English-speaking Canadian family physicians in active practices including patients 65 years and older. The 2003 Canadian Medical Directory was used to identify all physicians, sorted by province, with practice types listed as “family medicine” or “physician/general practice” and a preferred language of English because the survey was in English.16 Physicians whose preferred language was French, who make up about 25% of active family physicians,16 were excluded.

A stratified, simple random sampling strategy was used, with 5 strata corresponding to 5 regions of the country (BC, the Prairie provinces, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces). Nonproportional sampling fractions were applied such that 200 physicians were sampled within each stratum, for a total sample of 1,000 physicians. Sampling fractions ranged from 2% (Ontario) through 9% (Atlantic provinces) to 20% (Quebec).

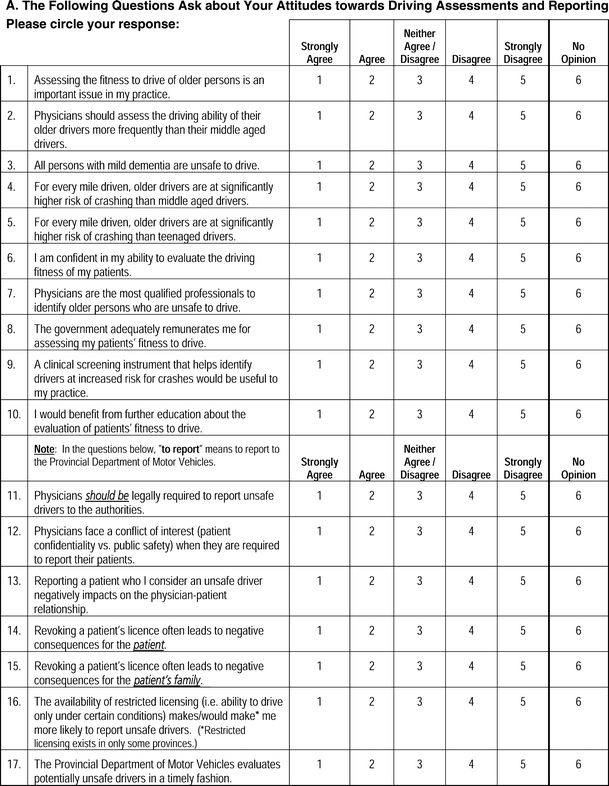

The content of the questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature and with consultations from family physicians, occupational therapists, geriatricians, and rehabilitation specialists with expertise in driving assessments. The questionnaire was pilot tested with 5 family physicians and revised based on their feedback. The survey started with a question to establish eligibility: “Are you in an active family practice that includes patients 65 years and older?” Those answering “no” were instructed to return the survey blank. The survey contained sections on (a) attitudes and practices towards driving assessments and the reporting of patients considered medically unsafe to drive; (b) components of assessments of older patients’ fitness to drive; (c) awareness of provincial reporting policies and procedures; and (d) information about the respondents (age, sex, years in practice), their medical practices, and their experience in performing fitness-to-drive assessments and reporting patients to the licensing authorities. The responses for most questions were on a 5-point ordinal scale (e.g., from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or “always” to “never”).

We adopted several techniques to maximize the response rate: personalization (a cover letter using the respondent’s name and ink signatures), self-addressed and prestamped return envelopes using first-class stamps, a token of appreciation not conditional on response (a Canadian $2 bill, now out of circulation), and up to 5 contacts for each subject (a prenotice letter, the initial survey mailing, a reminder postcard, and up to 2 additional survey mailings).17,18 To ensure confidentiality, the surveys were administered anonymously, with no identifiers on the questionnaire or return envelope. Physicians were instructed to return an enclosed postcard with their identification information separately from their completed survey, enabling the identification of respondents but not their responses. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute.

The response rate was calculated using the proportional allocation method, which assumes that the proportion eligible among those who did not reply and whose mailing was returned undelivered is the same as the proportion eligible among responders.19 This method results in a conservative estimate of the response rate because it tends to overestimate the eligibility of nonresponders.

Because the survey was administered anonymously, we could not directly compare the characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents and could not use the same source of information to compare the characteristics of the respondents and the target sample of 1,000 physicians. The characteristics of the respondents were obtained from responses to the mailed questionnaire, while the characteristics of the target sample of 1,000 physicians were derived from data from the Canadian Medical Directory.16 For the target sample of physicians, the number of years of practice was estimated from their year of graduation from medical school plus 2 years of postgraduate training, and the community size for their city of practice was obtained from 2001 census information from Statistics Canada (http://www.statscan.ca).

Sampling weights were used to adjust the response frequencies for the nonproportional sampling scheme. The adjusted frequencies, which are estimates of the total Canadian population frequencies, are presented here. A weighted Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare response profiles between physicians in provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting of unsafe drivers.20 Physicians in BC were excluded from these comparisons because of the unique reporting legislation in that province, which falls somewhere between full mandatory and discretionary reporting of unsafe drivers.

Survey-weighted regression models were used to explore the effect on responses to key questions of 4 factors chosen a priori: (a) physicians’ years in practice, (b) the size of the community they practiced in, (c) the region they worked in, and (d) the proportion of their practice aged 65 years or older. For questions with ordinal responses (e.g., number of fitness-to-drive assessments performed, confidence in ability to evaluate driving fitness, whether physicians should be legally required to report unsafe drivers, whether cognitive assessment is included in the driving assessment), the continuation ratio regression model was used.21 For the question collapsed into a binary outcome (number of patients reported to the driving authorities; 0 or >1), binary logistic regression was used. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons.22 For the analysis investigating the association between the time taken to complete a driving assessment and the number of components assessed, a survey-weighted Poisson regression model using polynomial contrasts for time of assessment was fitted. A response of “often” or “always” was treated as having assessed the component. Analyses were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (http://www.r-project.org/) using the survey package, version 3.6-1 (http://faculty.washington.edu/tlumley/survey/).

The sample size was selected by evaluating the expected statistical properties of a range of sample sizes and response rates. Assuming a 50% response rate, a sample of 200 physicians from each region was considered adequate because it met the following criteria: (a) the standard error of the estimate of the proportion of physicians who endorsed a given response would be, at most, 2.7 percentage points, and (b) for comparisons across provinces with mandatory and discretionary reporting legislation, with alpha = 0.05 and power = 80%, if the percentage of respondents endorsing a response in provinces without legislation was 15%, 25%, 35%, or 50%, the minimum detectable differences would be 9.1%, 11.1%, 12.2%, and 12.8%, respectively.

RESULTS

The outcome for each of the 1,000 mailed questionnaires is listed in Table 1, according to the guidelines of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.23 The response rate was 66.9% using the proportional allocation method.19

Table 1.

Outcomes of the 1,000 Mailed Questionnaires

| Final Outcome | Number |

|---|---|

| Eligible, returned questionnaires | 460 |

| Complete | 445 |

| Partial* | 15 |

| Eligible, nonresponse† | 21 |

| Refusal | 9 |

| Implicit refusal | 12 |

| Not eligible‡ | 219 |

| Unknown eligibility, no returned questionnaire | 300 |

| Nothing ever returned | 256 |

| Unknown whereabouts, mailing returned undelivered | 44 |

*A partial questionnaire is defined as a questionnaire with at least one section (out of 5 sections) left blank. Of the 15 partial questionnaires, 13 had 1 section blank and 2 had 2 sections blank

†A refusal is defined as a questionnaire that is returned blank with an explanation other than noneligibility (e.g., not enough time). An implicit refusal is defined as a questionnaire returned blank with no explanation and with the eligibility question unanswered

‡Lack of eligibility was established by a returned blank questionnaire with the eligibility question answered as “no”

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the eligible respondents who returned their questionnaires and of the target sample of 1,000 physicians. In general, for the characteristics available for comparison, the characteristics of the respondents and the target sample of physicians appear quite similar.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Respondents and Target Sample of 1,000 Physicians

| Characteristic | Respondents % | Target sample % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | N* = 455 | |

| Female | 30.1 | 31.6 |

| Years in practice | N = 455 | |

| <10 | 21.2 | 20.9 |

| 11–20 | 35.3 | 29.6 |

| 21–30 | 29.4 | 29.9 |

| 31–40 | 10.8 | 14.2 |

| >40 | 3.3 | 5.4 |

| Province of practice | N = 460 | |

| British Columbia | 20.7 | 20.0 |

| Prairie Provinces | 18.5 | 20.0 |

| Alberta | 10.9 | 11.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| Manitoba | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Ontario | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Quebec | 19.1 | 20.0 |

| Atlantic provinces | 20.7 | 20.0 |

| New Brunswick | 5.7 | 5.2 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| Nova Scotia | 7.8 | 8.1 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| More than 1 province | 0.4 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0.7 | 0 |

| Size of practice community | N = 455 | |

| <10,000 | 23.1 | 20.4 |

| 10,000–50,000 | 18.9 | 18.4 |

| 50,001–100,000 | 12.7 | 14.5 |

| 100,001–500,00 | 16.9 | 15.5 |

| >500,000 | 28.4 | 31.2 |

| Number of patients in practice | N = 445 | |

| <500 | 5.2 | |

| 500–1,000 | 13.7 | |

| 1,001–2,000 | 38.2 | |

| 2,001–3,000 | 22.5 | |

| >3,000 | 20.4 | |

| % patients >65 y old | N = 449 | |

| <10% | 10.0 | |

| 10–30% | 47.7 | |

| 31–60% | 35.4 | |

| 61–90% | 6.0 | |

| >90% | 0.9 | |

Respondents refer to eligible respondents who returned completed questionnaires. The characteristics of the respondents were obtained from the responses to the mailed questionnaire, while the characteristics of the total sample of 1,000 physicians were derived from data from the Canadian Medical Directory (CMD).16 The CMD does not include information for individual physicians about the number of patients in their practice or percentage of their patients 65 years and older, so this information was left blank for the total sample of physicians

*The N values for the respondents refer to the number who provided a response to the question relating to each characteristic

Table 3 presents the weighted response frequencies for selected survey questions. Most physicians consider the assessment of the fitness to drive of older persons to be an important issue in their practice, but 45.8% do not feel confident in assessing the driving fitness of their patients and 46.7% do not feel that physicians are the most qualified professionals to identify unsafe older drivers. Despite a majority view that reporting unsafe drivers poses a conflict of interest and carries negative consequences for patients and the physician–patient relationship, 72.4% agree that physicians should be legally required to report unsafe drivers to the authorities. A higher proportion of respondents from provinces with mandatory reporting agree with mandatory reporting legislation, but this did not reach statistical significance (73.3 vs 62.1%, P = .07).

Table 3.

Weighted Frequency of Responses for Selected Survey Questions (%)

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree/disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | |||||||||

| 1. Assessing the fitness to drive of older persons is an important issue in my practice. (N = 454) | 24.2 | 55.0 | 13.3 | 5.8 | 1.7 | ||||

| 2. Physicians should assess the driving ability of their older drivers more frequently than their middle-aged drivers. (N = 454) | 22.2 | 60.8 | 12.3 | 4.1 | 0.7 | ||||

| 3. I am confident in my ability to evaluate the driving fitness of my patients. (N = 448) | 3.4 | 27.0 | 23.8 | 36.5 | 9.3 | ||||

| 4. Physicians are the most qualified professionals to identify older persons who are unsafe to drive. (N = 449) | 2.3 | 24.5 | 26.4 | 35.7 | 11.0 | ||||

| 5. I would benefit from further education about the evaluation of patients’ fitness to drive. (N = 452) | 34.2 | 54.4 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| 6. A clinical screening instrument that helps identify drivers at increased risk for crashes would be useful to my practice. (N = 451) | 41.7 | 51.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 0.3 | ||||

| 7. Physicians face a conflict of interest (patient confidentiality vs public safety) when they are required to report their patients. (N = 453) | 19.4 | 55.0 | 8.0 | 14.9 | 2.7 | ||||

| 8. Reporting a patient who I consider an unsafe driver negatively impacts on the physician–patient relationship. (N = 456) | 21.8 | 56.0 | 12.5 | 8.3 | 1.5 | ||||

| 9. Revoking a patient’s license often leads to negative consequences for the patient. (N = 457) | 19.8 | 55.3 | 13.6 | 9.9 | 1.4 | ||||

| 10. Revoking a patient’s license often leads to negative consequences for the patient’s family. (N = 450) | 14.4 | 45.3 | 18.8 | 20.2 | 1.3 | ||||

| 11. Physicians should be legally required to report unsafe drivers to the authorities. (N = 448) | 19.0 | 53.4 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 3.3 | ||||

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | <10 min. | 10–20 min. | 21–30 min. | >30 min. | |

| Practices | |||||||||

| 1. I use the Canadian Medical Association handbook Determining Medical Fitness to Drive—A Guide for Physicians when assessing my patients’ fitness to drive. (N = 339)* | 11.8 | 29.4 | 27.7 | 17.0 | 14.2 | ||||

| 2. How long do you typically spend in assessing a patient’s fitness to drive? (N = 425) | 4.1 | 39.3 | 40.8 | 15.8 | |||||

All the response frequencies are reported as percentages. The N values represent the number of responses received for each question

*This N value includes only the number of responses for those who indicated that they were aware of the handbook

Most physicians feel that they would benefit from further education about driving assessment and from a screening instrument to identify high-risk drivers. Nearly one quarter of physicians (23.5%) are not aware of the Canadian Medical Association handbook Determining Medical Fitness to Drive: A Guide for Physicians,6 and 31.2% of those who are aware of it rarely/never use it. There was no significant difference in the use of the handbook by physicians from provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting (P = .95).

Table 4 describes the weighted frequencies of performing driving assessments and of reporting patients who are unfit to drive to the licensing authorities. Physicians in provinces with mandatory reporting assess fewer patients (P < .001) but report more (P = .02). The majority who reported patients to the licensing authorities in the previous year only reported 1 to 2. Cross tabulations of number of assessments with number of drivers reported were calculated for provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting. For each category of number of assessments done (i.e., 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, >10), physicians in provinces with mandatory reporting reported a higher percentage of patients than physicians in provinces with discretionary reporting did (results not shown). Multiple regression analyses (see Table 5) revealed that having a higher proportion of older patients in one’s practice was associated with a higher odds of conducting driving assessments and of reporting unsafe drivers, while practicing in a province with mandatory reporting of unsafe drivers was associated with a lower odds of conducting assessments but a higher odds of reporting.

Table 4.

Weighted Frequencies of Number of Fitness-to-Drive Assessments Performed and Number of Patients Reported to the Licensing Authorities in the Past Year by Region

| % of respondents | P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandatory reporting provinces (N = 182 and 184) | Discretionary reporting provinces (N = 170 and 172) | British Columbia (N = 94 and 94) | All provinces (N = 451 and 455) | ||

| No. of driving assessments | |||||

| 0 | 15.3 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 10.7 | <.001 |

| 1–2 | 24.0 | 13.7 | 6.4 | 18.3 | |

| 3–5 | 31.1 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 22.4 | |

| 6–9 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 13.8 | 9.8 | |

| ≥10 | 20.5 | 65.1 | 66.0 | 38.8 | |

| No. of unsafe drivers reported | |||||

| 0 | 29.8 | 41.5 | 31.9 | 32.6 | .02 |

| 1–2 | 46.1 | 44.4 | 53.2 | 47.2 | |

| 3–5 | 20.5 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 17.8 | |

| 6–9 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 2.3 | |

| ≥10 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

The N values represent the number of responses received for the question on driving assessments and drivers reported, respectively

*P value from weighted Pearson’s chi-squared analysis comparing response profiles of physicians in provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting of unsafe drivers

Table 5.

Odds Ratios for Physicians Performing Fitness-to-Drive Assessments and Reporting Patients who are Unsafe to Drive to the Licensing Authorities

| Variable | Performing driving assessments | Reporting unsafe drivers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR* (and 95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR* (and 95% CI) | P value | |

| Years in practice (per 5-y increment) | 1.11 (0.99–1.23) | 0.07 | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) | 0.32 |

| Proportion of patients 65+ in practice (vs <10%) | ||||

| 10–30% | 2.29 (1.15–4.57) | 0.02 | 4.66 (1.42–15.25) | 0.005 |

| 31–60% | 2.98 (1.51–5.88) | 0.002 | 9.77 (2.79–34.27) | <0.001 |

| 61–90% | 4.96 (1.95–12.65) | 0.001 | 85.87 (11.59–636.40) | <0.001 |

| Mandatory requirement to report unfit drivers (vs discretionary reporting) | 0.58 (0.39–0.85) | 0.006 | 2.78 (1.58–4.91) | 0.001 |

Odds ratios were derived from survey-weighted multiple regression analyses using a continuation-ratio model for predictors of the frequency of performing driving assessments (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, ≥10) and a logistic regression model for predictors of the odds of reporting (0 or ≥1). An odds ratio greater than 1 corresponds with a higher frequency of driving assessments and a greater odds of reporting unsafe drivers. Significant results are in bold

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

*The OR for each variable is adjusted for all other variables in the table, as well as for the size of the community in which the physicians practiced

The reporting practices of physicians were asked for 3 different scenarios, as outlined in Table 6. The only significant difference between physicians from provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting was that physicians from mandatory reporting provinces are more likely to report an unsafe driver who agrees to stop driving (P < .001).

Table 6.

Weighted Frequencies of Reporting Patients to the Licensing Authorities for Specific Scenarios

| Reporting frequency % | P value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||

| Patient unsafe to drive, but agrees to stop driving | ||||||

| Provinces with mandatory reporting | 38.3 | 22.3 | 18.6 | 13.0 | 7.9 | <.001 |

| Provinces with discretionary reporting | 18.2 | 17.5 | 21.5 | 28.4 | 14.4 | |

| British Columbia | 22.8 | 20.7 | 29.3 | 15.2 | 12.0 | |

| All provinces | 31.0 | 21.0 | 21.4 | 16.6 | 10.1 | |

| Patient unsafe to drive, but refuses to stop driving | ||||||

| Provinces with mandatory reporting | 67.5 | 21.9 | 9.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | .20 |

| Provinces with discretionary reporting | 61.8 | 22.5 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 3.1 | |

| British Columbia | 70.8 | 22.5 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 0.0 | |

| All provinces | 67.0 | 22.2 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Physician is unsure whether the patient is safe to drive | ||||||

| Provinces with mandatory reporting | 10.3 | 28.0 | 30.4 | 22.0 | 9.3 | .97 |

| Provinces with discretionary reporting | 10.7 | 25.4 | 29.5 | 23.0 | 11.4 | |

| British Columbia | 12.9 | 32.3 | 31.2 | 16.1 | 7.5 | |

| All provinces | 10.9 | 28.3 | 30.4 | 21.0 | 9.4 | |

*P value from weighted Pearson’s chi-squared analysis comparing response profiles of physicians in provinces with mandatory versus discretionary reporting of unsafe drivers

Table 7 shows the variability of the components included in physicians’ assessments of older patients’ fitness to drive. A patient history of driving crashes and infractions and cognitive testing are often/always obtained by less than half of physicians. Physicians from provinces with mandatory reporting are more likely to obtain a driving history (P = .02), do cognitive testing (P = .007) and an ECG (P = .005), and refer patients to a specialist (P < .001) and for a geriatric assessment (P = .02). Physicians from provinces with discretionary reporting are more likely to do cardiac (P < .001), hearing (P = .003), and joint exams (P = .05) and to refer patients for a road test (P = .04).

Table 7.

Weighted Frequencies of Carrying Out Various Components of Fitness-to-Drive Assessments in Older Patients (%)

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||

| Medical history | 65.3 | 27.3 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| Medication review | 64.7 | 24.5 | 9.2 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| Alcohol history | 57.6 | 28.6 | 10.8 | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| Collateral driving history | 19.2 | 33.2 | 30.6 | 12.2 | 4.8 |

| History of driving accidents | 18.5 | 26.5 | 26.3 | 17.0 | 11.7 |

| History of driving infractions | 9.9 | 22.3 | 22.6 | 26.1 | 19.1 |

| Physical exam | |||||

| Visual acuity exam | 61.9 | 26.9 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 0.2 |

| Cardiac exam | 50.4 | 27.7 | 15.0 | 6.9 | 0.0 |

| Neurologic exam | 34.2 | 33.8 | 24.2 | 6.7 | 1.1 |

| Hearing exam | 37.6 | 28.9 | 21.5 | 10.9 | 1.1 |

| Visual fields exam | 44.0 | 22.1 | 17.3 | 11.9 | 4.7 |

| Joint exam | 24.1 | 24.9 | 31.9 | 15.0 | 4.0 |

| Cognitive testing (e.g., MMSE) | 16.7 | 32.1 | 33.9 | 13.1 | 4.1 |

| Tests | |||||

| ECG | 8.5 | 19.2 | 37.0 | 25.1 | 10.2 |

| Referrals | |||||

| Referral to a medical specialist | 4.8 | 18.7 | 45.7 | 24.5 | 6.2 |

| Referral for a road test by the province | 3.4 | 20.1 | 41.9 | 22.0 | 12.6 |

| Referral for a geriatric assessment | 2.4 | 20.1 | 36.4 | 29.7 | 11.3 |

| Referral for a road test by a third-party center | 2.6 | 10.8 | 22.0 | 23.2 | 41.5 |

All the response frequencies are reported as percentages. Components of the assessment that are done always/often by at least 50% of respondents are in bold

MMSE mini-mental state examination

Most driving assessments take between 10 and 30 minutes, with 39.3% taking 10–20 minutes and 40.8% taking 20–30 minutes (Table 3). Physicians from provinces with mandatory reporting spend a significantly greater amount of time conducting assessments (P = .04). A positive linear relationship was found between the time taken to conduct the assessment and the number of components included in the assessment (P < .001).

DISCUSSION

Many physicians do not feel confident or qualified in assessing the driving fitness of their patients. The majority feel that reporting patients who are unsafe to drive to the licensing authorities puts them in a conflict of interest and has negative consequences for patients, patients’ families, and the patient–doctor relationship. Despite these misgivings, almost three quarters agree that physicians should be legally required to report unsafe drivers.

These findings are consistent with a study from Saskatchewan, Canada that found that while most of that province’s physicians (58.1%) felt that reporting unsafe drivers negatively affected the physician–patient relationship, an overwhelming majority (92.5%) indicated that the interests of the public should prevail over the needs of the individual driver.11 Similarly, a survey of 467 geriatricians in the United States found that 92.3% would report their unsafe drivers with dementia.24 However, our findings contrast with those from a survey of Canadian neurologists (N = 289) that found that only 44% of respondents were in favor of mandatory reporting by physicians.25 This difference may relate in part to the fact that neurologists, who provide care for patients with several of the leading conditions that affect driver safety (e.g., seizures, strokes, and dementias),26,27 may be concerned with the burden of having to report unsafe drivers, possibly making them more reluctant to take on the responsibility of mandatory reporting.

The high proportion of physicians who indicate that reporting a patient who is unfit to drive negatively impacts the physician–patient relationship underscores the need for physician training in how to communicate the need to stop driving to their patients. Our findings that many physicians lack confidence in their driving assessments and do not consider physicians to be the most qualified professionals to conduct these assessments highlights the need for further physician education about fitness-to-drive assessments. In fact, the vast majority of physicians indicate that they would benefit from further education in this area. This finding is consistent with a study of Finnish and Swedish general practitioners, which showed that only 21% of Finnish and 18% of Swedish physicians agreed with the statement “My training in traffic medicine is sufficient for assessing the driving fitness of older (65+) drivers.”27

Surprisingly, a large number of physicians in our survey were either not aware of, or did not use, the Canadian Medical Association handbook Determining Medical Fitness to Drive: A Guide For Physicians. This is in keeping with findings from an American study that found that 69% of the geriatricians were not aware of the American Medical Association guidelines regarding medical conditions affecting drivers.28 This suggests that physicians need to be made more aware of existing guidelines.

Our study found considerable variability in the reported components of the assessment of fitness to drive of older patients. Unexpectedly, less than half of the physicians often/always obtain a patient history of driving crashes and infractions or perform cognitive testing as part of their assessments. However, these findings are consistent with a study that showed that the majority of geriatricians did not keep a record of their patients’ driving status and that only 8% used mental status as a criterion for recommending driving cessation.28 It is possible that physicians focus exclusively on the presenting medical condition that is perceived to be the potential barrier to safe driving, or that physicians do not have a clear idea about what conditions are most important to screen for and what should be included in a thorough assessment for older drivers. Our findings are consistent with a Norwegian study that found that general practitioners had a variety of approaches to assessing fitness to drive29 and with an American study that found no clear consensus on the criteria used to recommend driving cessation.28 These findings suggest that greater standardization is needed on how physicians should assess their older patients’ medical fitness to drive.

Our study raises some interesting questions about the possible effects of mandatory reporting legislation on physician behavior. Paradoxically, physicians from provinces that require the reporting of unsafe drivers appear to perform fewer driving assessments than respondents from provinces with discretionary reporting do. The requirement to report, with its potential negative repercussions, may act as a disincentive for physicians to initiate a driving assessment.

Our study has some limitations. Although our response rate was not optimal, it was relatively high and consistent across regions. Because the survey was administered anonymously, we could not directly compare the characteristics of respondents with nonrespondents and we had to use different sources of information to compare the characteristics of respondents with the target sample of 1,000 physicians. Although it is reassuring that the respondent characteristics that we were able to compare with those of the target sample of physicians were quite similar, we cannot exclude the possibility of nonresponse bias. As is the case in all surveys, some of the responses may not reflect actual attitudes and practices. Social desirability bias may have influenced some of the responses, but the anonymity of the survey likely reduced this bias. Recall bias is a potential threat for the questions regarding physicians’ practices, but it is unlikely that physicians were very inaccurate about their practices. Lastly, because specialist physicians and physicians who primarily speak French were excluded from the survey, our results are not generalizable to these physicians.

In conclusion, while most Canadian family physicians do not believe that they are the most qualified to assess fitness to drive, and feel that this role puts them in a conflict of interest and negatively affects the patient–physician relationship, the majority feel that it should be the legal responsibility of physicians to report medically unsafe drivers to the licensing authorities. To aid physicians in this challenging role, our study suggests the need for additional physician education about how to conduct driving fitness assessments, greater standardization of the components of these assessments, and better communication strategies for physicians who need to inform their patients to stop driving.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments We would like to thank Sue Woodard for her administrative assistance and Sooyeol Lim for his assistance in the initial data analysis.This study was partially funded by the Geriatrics Fund, University Health Network and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canadian Driving Research Initiative for Vehicular Safety in the Elderly (http://www.CanDRIVE.ca). Dr. Jang was supported by a Faculty of Medicine Summer Research Scholarship (2003), University of Toronto. Dr. Naglie is supported by the Mary Trimmer Chair in Geriatric Medicine Research, University of Toronto. The Toronto Rehabilitation Institute receives funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Provincial Rehabilitation Research Program. Dr. Hogan is supported by the Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine, University of Calgary. An earlier version of this study was presented at the Canadian Geriatrics Society Annual General Meeting in Toronto on May 30th 2004, and at the Tri-University (University of Toronto, McMaster University, University of Western Ontario) Geriatric Resident Research Day in Toronto in June 2004.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix

Survey Questionnaire

Family Physicians’ Views on Driving Assessments in Older Persons

Are you in an active family practice that includes patients 65 years and older?

□Yes. Please complete the rest of the survey.

□No. Do not complete the rest of the survey, but please return it as well as the enclosed postcard.

References

- 1.Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Johansson K, Lundberg C. Medical screening of older drivers as a traffic safety measure—a comparative Finnish–Swedish evaluation study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996;44:650–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Brorsson B. The risk of accidents among older drivers. Scand J Soc Med 1989;17:253–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Stutts JC, Martell C. Older driver population and crash involvement trends, 1974–1988. Accid Anal Prev 1992;24:317–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gresset J, Meyer F. Risk of automobile accidents among elderly drivers with impairments or chronic diseases. Can J Public Health 1994;85:282–5. [PubMed]

- 5.Cerrelli E. Older drivers: The age factor in traffic safety. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1989 Feb. Report No.: DOT HS 807 402.

- 6.Canadian Medical Association. Determining medical fitness to drive: a guide for physicians. 6th edn. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Medical Association; 2000. Also available from: http://www.cma.ca/index.cfm/ci_id/18174/la_id/1.htm.

- 7.Reuben DB. Assessment of older drivers. Clin Geriatr Med 1993;9:449–59. [PubMed]

- 8.Rosenbloom S. Transportation needs of the elderly population. Clin Geriatr Med 1993;9:297–310. [PubMed]

- 9.Marottoli RA, Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, et al. Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms: Prospective evidence from the New Haven EPESE. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Marottoli RA, de Leon CFM, Glass TA, Williams CS, Cooney LM Jr, Berkman LF. Consequences of driving cessation: decreased out of home activity levels. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:S334–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Marshall SC, Gilbert N. Saskatchewan physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding assessment of medical fitness to drive. CMAJ 1999;160:1701–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang CC, Kosinski CJ, Schwartzberg JG, Shanklin AV. Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003.

- 13.Coopersmith H, Korner-Bitensky N, Mayo N. Determining medical fitness to drive: physicians’ responsibilities in Canada. CMAJ 1989;140:375–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Capen K. New court ruling on fitness-to-drive issues will likely carry “considerable weight” across country. CMAJ 1994;151:667.

- 15.Capen K. Are your patients fit to drive? CMAJ 1994;150:988–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Canadian Medical Directory [homepage on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.mdselect.com.

- 17.Dillman DA. Mail And Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd edn. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2000.

- 18.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002;324:1183–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Smith TW. A review of methods to estimate the status of cases with unknown eligibility. Report prepared for the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Standard Definitions Committee. Version 1.1, September 2003.

- 20.Rao JNK, Scott AJ. On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with proportions estimated from survey data. Annu Stat 1984;12:46–60.

- 21.Berridge DM, Whitehead J. Analysis of failure time data with ordinal categories of response. Stat Med 1991;10:1703–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990;1:43–6. [PubMed]

- 23.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, 4th edn. Lenexa, KS: AAPOR; 2006.

- 24.Cable G, Reisner M, Gerges S, Thirumavalavan V. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of geriatricians regarding patients with dementia who are potentially dangerous automobile drivers: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:14–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.McLachlan RS, Jones MW. Epilepsy and driving: a survey of Canadian neurologists. Can J Neurol Sci 1997;24:345–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Drickamer MA, Marottoli RA. Physician responsibility in driver assessment. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Henriksson P, Falkmer T, Lundberg C, Braekhus A. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward older drivers: a Finnish–Swedish comparison. J Appl Gerontol 2002;21:58–69. [DOI]

- 28.Miller DJ, Morley JE. Attitudes of physicians toward elderly drivers and driving policy. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;40:722–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Braekhus A, Engedal K. Mental impairment and driving licenses for elderly people—a survey among Norwegian general practitioners. Scand J Prim Health Care 1996;14:223–8. [DOI] [PubMed]