Abstract

In nature, genetic variation usually takes the form of a continuous phenotypic range rather than discrete classes. The genetic variation underlying quantitative traits results from the segregation of numerous interacting quantitative trait loci (QTLs), whose expression is modified by the environment. To uncover the molecular basis of this variation, we characterized a QTL (Brix9-2-5) derived from the green-fruited tomato species Lycopersicon pennellii. The wild-species allele increased glucose and fructose contents in cultivated tomato fruits in various genetic backgrounds and environments. Using nearly isogenic lines for the QTL, high-resolution mapping analysis delimited Brix9-2-5 to a single nucleotide polymorphism-defined recombination hotspot of 484 bp spanning an exon and intron of a fruit-specific apoplastic invertase. We suggest that the differences between the Brix9-2-5 alleles of the two species are associated with a polymorphic intronic element that modulates sink strength of tomato fruits. Our results demonstrate a link between naturally occurring DNA variation and a Mendelian determinant of a complex phenotype for a yield-associated trait.

Domesticated species represent only a small fraction of the variability available among their wild relatives. The use of saturated molecular linkage maps has enhanced our ability to study and exploit this exotic variation in plants and animals (1). The Mendelian resolution of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) was simplified with the development of nearly isogenic lines (NILs), in which a single genomic segment contains the QTL in an otherwise uniform genetic background. Such resources have enabled more accurate estimates of the number of QTLs that affect a trait, their mode of inheritance, and linkage relationships, up to a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) resolution (2, 3).

One of the major objectives in tomato breeding is to increase the content of total soluble solids (TSS or brix; mainly sugars and acids) in fruits, to improve taste and processing qualities. TSS in fruits of wild Lycopersicon species can reach up to 15% of the fruit's fresh weight, 3 times higher than in cultivated varieties. To resolve the genetic basis for this variation, a set of 50 introgression lines was developed from a cross between the green-fruited species Lycopersicon pennellii and the cultivated tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum. Each of the NILs contained a single restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)-defined L. pennellii chromosome segment, and together the lines provided complete coverage of the genome. Using this resource, it was possible to map 23 QTLs that increase brix (4).

One of these QTLs (Brix9-2-5) was mapped to a 9-centimorgan (cM) segment on chromosome 9 (5). Here, we further characterize this QTL with respect to its phenotypic effects and the mode of inheritance in different years of growth, environments, and genetic backgrounds. We report the map-based cloning of this QTL and show that it resides within the tomato apoplastic invertase, Lin5 (6).

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials.

The NILs for the open-field trial were planted in Akko (14–28 plants per NIL) in a completely randomized design. Agricultural practices and phenotypic measurements were as described previously (4). Fruit serum from six mature fruits from each plant was subjected to high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) for sugar composition determination (7). Glasshouse trials of the segregating recombinant families (48 plants per family) were conducted in Shekef in 1997 and 1998 in a completely randomized design.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with jmp v.3.1 software for Macintosh. Mean brix values were compared by using the “fit Y by X“ function and ”compare with control“ with an alpha level of 0.001 (8). The control phenotypic values were obtained by using cv. M82 for the open-field trials (Fig. 1) and the indeterminate line 17 for the glasshouse trials (Fig. 2). The additive effect (a), dominance deviation (d), and degree of dominance (d/a) were calculated as previously described (4). Using the recombinant families, Brix9-2-5 was mapped by RFLP genotyping and a two-step analysis: (i) In each recombinant family, the brix phenotypic value for the L. pennellii homozygotes was compared with that of line 17 and expressed as a percentage of the control (Figs. 3 and 4). (ii) Families containing recombined L. pennellii chromosome segments between defined markers were grouped, and the mean phenotypic effects for each of the groups were calculated (Fig. 3C).

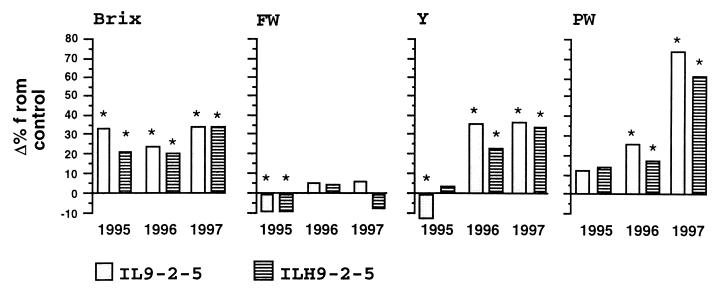

Figure 1.

Introgression line (IL) 9-2-5 effects in wide spacing over a 3-yr period for yield-associated traits: Brix, fruit weight (FW), yield (Y), and plant weight (PW). The mean effects of the IL (gray bars) and the hybrid with M82 (ILH9-2-5; hatched bars) are presented as percent difference from the control M82 (zero axis). * above a bar denotes a significant difference (P < 0.001) from the control. The mean values of the control, M82, for the three years (1995, 1996, and 1997, respectively) were: Brix (%): 4.5, 4.9, and 3.6; FW (g): 56, 51, and 63; Y (kg): 9.3, 7.9, and 7; and PW (kg): 1.8, 1.8, and 1.2.

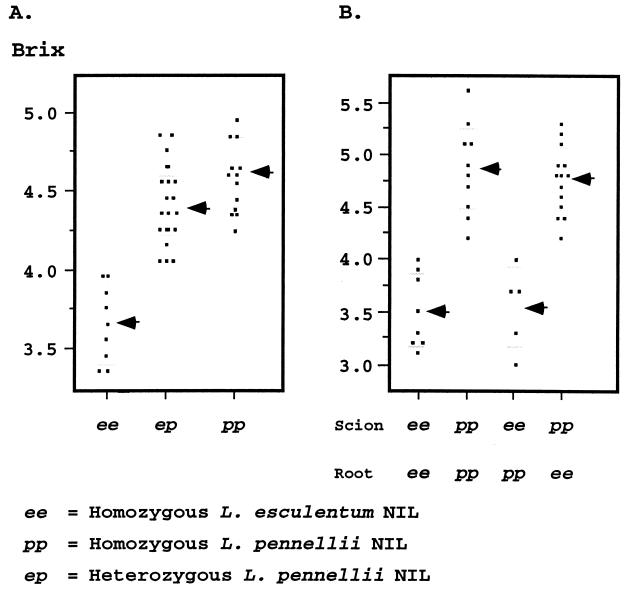

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of Brix9-2-5 in the indeterminate greenhouse background. (A) Brix values distribution for the three genotypes of a segregating BC5F2 family consisting of 47 plants segregating for the chromosome 9 introgression. The distribution for three genotypes is presented: homozygous for the L. esculentum segment (ee; 9 plants), heterozygous for the L. pennellii introgression (ep; 24 plants), and the homozygotes (pp; 14 plants). A black arrow and horizontal gray lines mark the mean value and the standard deviation for each genotype, respectively. (B) Brix values distribution of the four possible grafting combinations between the NILs ee and pp. The self-grafted controls (scion/root), ee/ee (8 plants) and pp/pp (10 plants); the reciprocal ee/pp (5 plants) and pp/ee (14 plants). A black arrow and horizontal gray lines mark the mean value and the standard deviation for each scion/root combination, respectively.

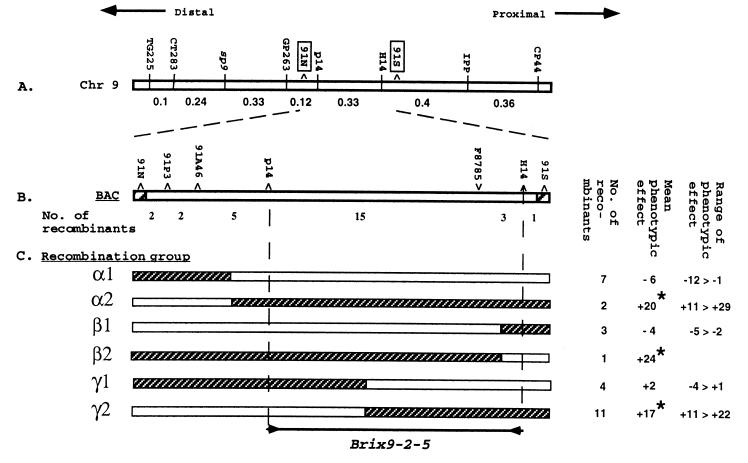

Figure 3.

Fine mapping and physical positioning of Brix9-2-5. (A) The genetic linkage map (in cM) of the chromosomal region of Brix9-2-5 oriented relative to the position of the centromere. The two end clones of BAC91A4, 91N and 91S, are boxed. (B) Genetically ordered markers on BAC91A4 and the number of recombinants between them. (C) Phenotypic analysis of the recombination groups in the bacterial artificial chromosome. Each group is composed of families whose genotype is represented by a bar divided into hatched (L. pennellii) and empty (L. esculentum) segments. The genomic composition of each group is defined by the longest L. pennellii segment that was detected in the included recombinant families. The borders between bars are arbitrarily drawn midway between markers positive and negative for the introgressed L. pennellii segment. To the right are the number of recombinants in the group, the mean phenotypic effect of the group, and the minimum and maximum effects in the included families. An asterisk indicates that the phenotypic effect of each of the included families was significant (P < 0.001). The genetically mapped interval of Brix9-2-5 is indicated by inward-facing arrows.

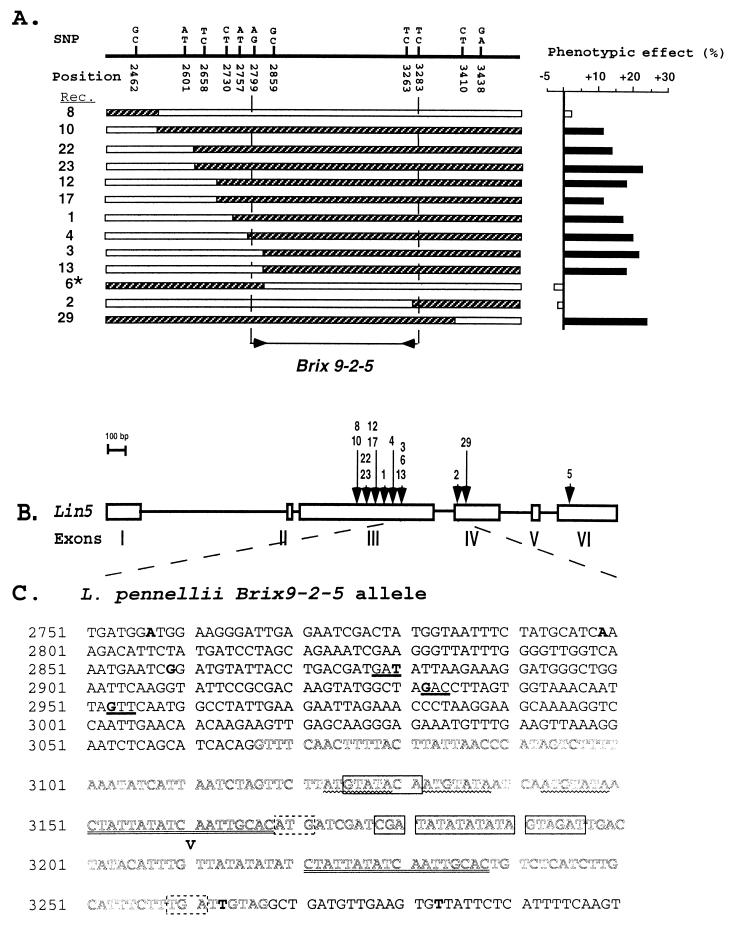

Figure 4.

(A) Nucleotide and phenotypic analysis of 13 recombinant families in Brix9-2-5. Each SNP is represented by its position in the L. pennellii (Top) and L. esculentum nucleotides. Solid black bars denote a significant phenotypic effect (P < 0.001). *, Phenotypic effect of family no. 6 was determined in the F4 generation. The physical location of Brix9-2-5 is indicated by inward-facing arrows between SNPs 2799 and 3283. (B) Genomic structure of Lin5. Boxes depict exons and the arrows represent the recombination points for each of the individual recombinant families (numbered above). (C) Genomic sequence of the L. pennellii Lin5 region that spanned the QTL. Nucleotides are numbered from the start codon of Lin5. SNPs between the two species are in bold. The codons for the three amino acid substitutions are underlined: positions 2878 (Asp in L. pennellii to Glu in L. esculentum), 2932 (Asp to Asn) and 2953 (Val to Leu). The intron is in outlined double-spaced letters. Deleted nucleotides in the L. esculentum sequence are boxed and a 4-bp insertion (ATCT) after base 3210 is indicated by a “V”. The 18-bp direct repeat is double-underlined, and the 7-bp repeats are marked with wavy lines. The start and end codons of the hypothetical ORF are in dashed boxes.

Nucleic Acid Analysis.

The different segregating populations were subjected to RFLP analysis as previously reported (5). BAC91A4 was subcloned into the pBS vectors (Promega) that were sequenced and assembled by using the sequencher software package. DNA from the homozygous recombinants in the F3 generation was used as a substrate for PCR, using the primers 5′-TTTGGGCTCATTCAGTCTCA and 5′-AAATTGTTCGGCCTCGTT to amplify a 1,200-bp portion of the Lin5 gene. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced by using the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). PCR was performed by using PCR Supermix (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) with 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 52°C, and 1 min at 68°C, followed by 30 min at 68°C.

Results and Discussion

Phenotypic Effects of Brix9-2-5.

Plants of cv. M82, homozygous for the L. esculentum allele of the QTL, the NIL homozygous for the L. pennellii allele, and their F1 hybrids were grown in an open field over a 3-yr period (Fig. 1). Based on sampling of individual plants for brix of red fruits, fruit weight, total fruit yield, and plant canopy weight, it was determined that brix was the only trait that showed no interaction with year, and the effect of Brix9-2-5 was found to be partially dominant (a = 0.65, d = 0.45). Analysis of the fruit serum showed that the variation in brix was attributable to a significant (P < 0.001) increase in glucose (+28%) and fructose (+18%), but not in acids. The differences in brix between the NILs were largely independent of the negatively correlated traits, fruit weight and yield. In 1995, the introgression reduced fruit weight and yield, but, in 1996 and 1997, fruit weight was not affected and yield was increased by approximately 30%; yet, the brix values were similar in all years. Brix is sometimes positively correlated with plant canopy weight (9), but, in the 3-yr trial, brix was largely independent of plant weight.

The wild-species allele of Brix9-2-5 was backcrossed to an indeterminate line for glasshouse cultivation. The major difference between the glasshouse and open-field varieties relates to the growth habit of the plant. Open-field varieties are homozygous for the recessive mutation self-pruning (sp) that modifies plant architecture, leading to a successive reduction of the number of leaves between inflorescences, and, as a result, fruit set is concentrated (10). Glasshouse varieties are indeterminate (Sp_) and follow a developmental program of three leaves between the inflorescences leading to fruit production over an extended period and to higher source to sink ratio than determinate plants. Two indeterminate NILs were crossed, and F2 family analysis revealed that the L. pennellii allele is also effective in the glasshouse (brix increase of 27%, a = 0.5, d = 0.25; Fig. 2A). Although the fruit mainly import sugars directly from the leaves, the root system may reexport assimilates as amino acids or organic acids (11). To test whether the QTL was affecting brix through the above-ground portion of the plant, we used a reciprocal grafting approach where the NILs functioned as reciprocal scion and root (Fig. 2B). In the control treatment, the NILs were self-grafted and generated brix phenotypes and distributions that were very similar to the nongrafted lines. When the line containing the introgression (pp) served as the rootstock for its isogenic line (ee), the phenotype was similar to the control self-grafted line (scion/root; ee/ee). When line ee was the root and pp was the scion (pp/ee), brix was similar to the control introgression NIL. These treatments indicated that the QTL functions in the above-ground shoot. Furthermore, these phenotypes and their distributions established the reliability of the experimental system for inferring the genotypes of individual plants with respect to Brix9-2-5.

Map-Based Cloning of Brix9-2-5.

To map the QTL, 7,000 F2 progeny of the NIL hybrid were subjected to RFLP analysis with the markers CP44 and TG225, revealing 145 recombinants [1 centimorgan (cM) compared with 9 cM between the same markers in the F2 generation resulting from selfing of the interspecific hybrid (5)]. Such 10-fold reduction in recombination frequencies is often observed when exotic chromosome segments are introgressed into cultivated background (12). Of the 145 recombinants identified, 28 were further localized between the two ends of BAC91A4 (Fig. 3 A and B; mapping and bacterial artificial chromosome contig data at a lower resolution are not presented). For each of the 28 recombinant families, 48 selfed progenies were genotyped with the appropriate segregating markers and analyzed for brix. To simplify data representation, we subdivided the 28 recombinant families into 6 recombination groups (Fig. 3C). Group α1 includes the recombinants between 91N and 91P3 (two families), 91P3 and 91A46 (two families), and between 91A46 and p14 (three families). The later three families, which contain the longest introgressed segment in the α1 group, were used to set the limits for the combined graphical representation of the group. None of the recombinants in group α1 showed a significant effect on brix. The reciprocal recombination group α2 contained two families with a L. pennellii segment proximal to p14 and showed a significant increase in brix. The α groups placed the QTL proximal to 91A46. Using the same procedure, groups β and γ located Brix9-2-5 between H14 and p14. To further narrow the position of Brix9-2-5, the 18 kb spanning p14 and H14 were sequenced and used to design different primer pairs that amplified polymorphic products (in size or restriction pattern) between the parental lines. These products were genetically mapped by using the 28 recombinants and one of these primer pairs (F8785, Fig. 3B), which amplified a fragment of approximately 1 kb, showed a complete cosegregation with the QTL. This interval was sequenced for the parental types and the recombinants, and based on the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 13 families were shown to be recombinants within this 1-kb fragment. The phenotypic effects for each of the 13 families were used to determine the location of Brix9-2-5 on the SNP map (Fig. 4A). Recombinants 3, 13, and 6 delimited Brix9-2-5 to a region downstream of 2799 in a manner consistent with the mapping of the rest of the recombinant families. Recombinant 2 delimited the QTL to the region upstream of 3283, a conclusion that is in agreement with the mapping of recombinants 5 (a member of group β1; Fig. 3C) and 2. Thus, SNP mapping allowed the unequivocal placement of Brix9-2-5 to a 484-bp interval between positions 2799 and 3283.

Brix9-2-5 Resides in an Invertase Domain.

A search of GenBank revealed that the QTL interval contained regions encoding a Lycopersicon apoplastic invertase (Lin5) that is expressed exclusively in flowers and fruits (6). A comparison of the genomic and Lin5 cDNA sequences resolved six exons in Lin5 and located the 484-bp interval to exon 3, intron 3, and the 5′ portion of exon 4 (Fig. 4B). Lin5 is a member of a small family of genes encoding apoplastic invertases. These extracellular enzymes are hydrolases, cleaving sucrose to glucose and fructose, which are then transported into the cell. This activity maintains a gradient of assimilates, from the source parts of the plant to the developing sink tissues. In addition to sucrose hydrolysis, invertases play a central role in regulating, amplifying, and integrating different signals that lead to the source–sink transition (13). The activity of this enzyme changes the sugar influx, and this alters the expression of sugar-responsive genes in a manner that is not yet clear (14, 15).

Comparison of the L. pennellii and L. esculentum sequences revealed several differences that may be responsible for the effect of Brix9-2-5 (Fig. 4C): (i) The peptide sequence of the two species unraveled three amino acid changes that may affect protein function. However, in view of the generally neutral effects of such substitutions, we suggest that the QTL is associated with a regulating function of the third intron. (ii) The L. pennellii intron was longer than its corresponding sequence in L. esculentum (201 vs. 179 bp) and included two perfect 18-bp direct repeats, whereas in L. esculentum there was a difference of one nucleotide between the repeats. L. pennellii carried a 7-bp triple repeat 5′ to the first direct repeat, whereas in L. esculentum one of the repeats was deleted. These repeats may regulate the expression of Lin5 or other genes, as was recently demonstrated for a 73-bp enhancer with similar structures in rats (16). (iii) A potentially important difference between the alleles of the two species relates to the downstream sequence of the first 18-bp direct repeat. Starting from position 3169, in L. pennellii there is a hypothetical ORF of 30 amino acids (with no homologies in GenBank), whereas in L. esculentum there is a 19-bp deletion followed by stop codons. The above description of some of the structural components of the 484-bp QTL implicates a plethora of potential biological control points that might be responsible for the differences in fruit sugar content. The complexity of factors modulating quantitative phenotypic effects was recently dissected in Drosophila. Differences in alcohol dehydrogenase activity between two allozymic classes were located to an intron, the coding sequence, and the 3′ untranslated region, showing that effects of a single locus may be because of multiple associated polymorphisms (17). If we are to determine the physiological basis of complex traits, it is necessary to clone the genes and devise molecular and genetic complementation approaches that are sensitive enough to detect minor variations in gene expression pattern and function. Our preliminary results confirmed that Lin5 transcripts are found exclusively in developing carpels and young fruits; however, no clear differences were detected between the Brix9-2-5 NILs.

The Recombination Hotspot.

In this research, a recombination hotspot created multiple isogenic chimeric alleles that delimited the QTL to a defined sequence. The precise mapping of the quantitative effect was facilitated by the nearly isogenic nature of the phenotyped segregating populations, whereby all of the variation for the quantitative trait was associated with the introgressed segment. The hotspot, which may be associated with potential secondary structures formed by the direct repeats in intron 3, created 13 recombinants within 948 bp compared with only 15 recombinants for the rest of the 100-kb bacterial artificial chromosome. This observation is consistent with studies in maize, where intragenic recombination frequencies were found to be several times greater than recombination between genes (18).

Much of our understanding of development is based on the analysis of loss-of-function mutants. However, the variation of greatest interest is often quantitatively inherited, originates from natural populations, and is associated with regulation functions. In a recent study of wild-species-derived alleles that modify carotenoid biosynthesis in tomato, it was determined that the orange color of the partially dominant mutants Del (high δ-carotene) and B (high β-carotene) result from differential expression patterns during fruit ripening of the genes coding for ɛ-cyclase and a β-cyclase, respectively (ref. 19; and G. Ronen, personal communication). Similarly, the vacuolar invertase was found to be expressed earlier in fruits of the wild species Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium as compared with the cultivated L. esculentum (20). Further evidence of the importance of wild germplasm in unraveling regulatory functions of genes is derived from the analysis of a key gene in maize domestication, teosinte-branched1 (tb1) (21). Polymorphism between maize and its progenitor teosinte for tb1 indicated that the effects of human selection during domestication were limited to the gene's regulatory region and did not extend to the protein-coding region. Our results suggest that the complex phenotype of total soluble solids in tomato fruits may also be determined at the regulatory level. Brix9-2-5 highlights the potential of wild-species alleles for unraveling variations associated with agricultural production. Such identification of rate-limiting pathways for yield and quality in model species may lead to the development of improved varieties in other crop plants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Eshed, M. Shoresh, and R. Fluhr for useful comments; T. Melman and the Sequencing Unit at the Weizmann Institute, R. Wing, and D. Frisch from the Clemson University Genomics Institute for the bacterial artificial chromosomes; and P. Hedley for the gift of the potato invertase clone. This work was supported in part by The United States–Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund and The Israeli Ministry of Science.

Abbreviations

- Lin

Lycopersicon invertase

- NIL

nearly isogenic line

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- RFLP

restriction fragment length polymorphism

Footnotes

References

- 1.Paterson A H, editor. Molecular Dissection of Complex Traits. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamir D, Eshed Y. In: Molecular Dissection of Complex Traits. Paterson A H, editor. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1998. pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpert K B, Tanksley S D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15503–15507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eshed Y, Zamir D. Genetics. 1995;141:1147–1162. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eshed Y, Zamir D. Genetics. 1996;143:1807–1817. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.4.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godt D E, Roitsch T. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:273–282. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin I, Gilboa N, Yeselson E, Shen S, Schaffer A A. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;100:256–262. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunnet C W. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emery G C, Munger H M. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 1970;95:410–412. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pnueli L, Carmel-Goren L, Hareven D, Gutfinger T, Alvarez J, Ganal M, Zamir D, Lifschitz E. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1979–1989. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall T C, Cocking E C. Plant Cell Physiol. 1966;7:329–341. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rick C M. Genetics. 1969;62:753–768. doi: 10.1093/genetics/62.4.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roitsch T. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:198–206. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturm A, Tang G Q. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber H, Roitsch T. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:47–48. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung C F, Penning T M. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1704–1717. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stam L F, Laurie C C. Genetics. 1996;144:1559–1564. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooner H K, Martinez-Ferez I M. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1633–1646. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ronen G, Cohen M, Zamir D, Hirschberg J. Plant J. 1999;17:341–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott K J, Butler W O, Dickinson C D, Konno Y, Vedvick T S, Fitzmaurice L, Mirkov T E. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;21:515–524. doi: 10.1007/BF00028808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R L, Stec A, Hey J, Lukens L, Doebley J. Nature (London) 1999;398:236–239. doi: 10.1038/18435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]