Abstract

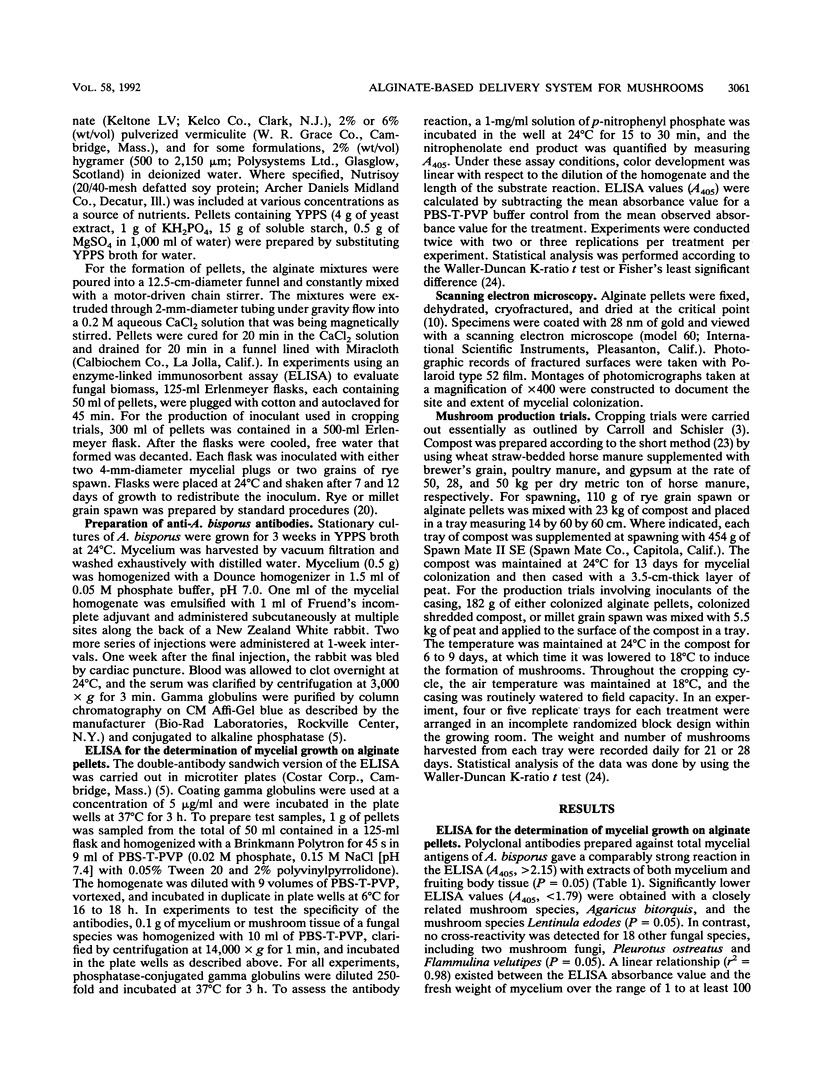

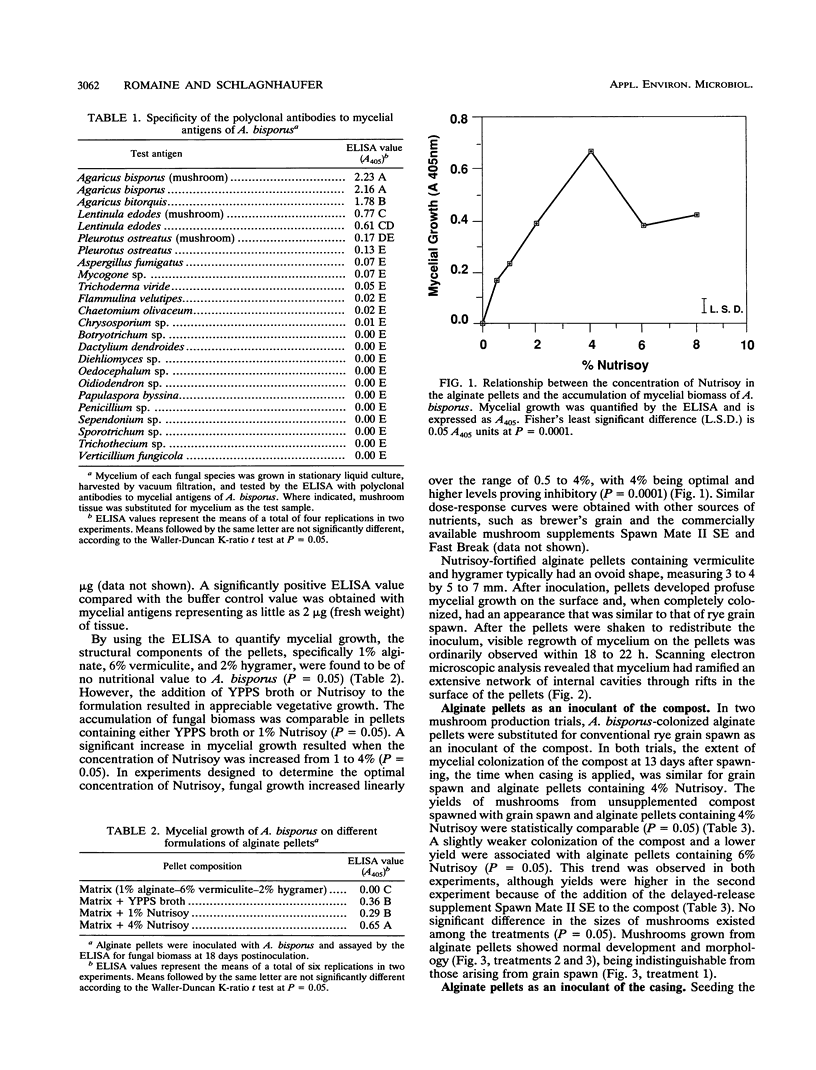

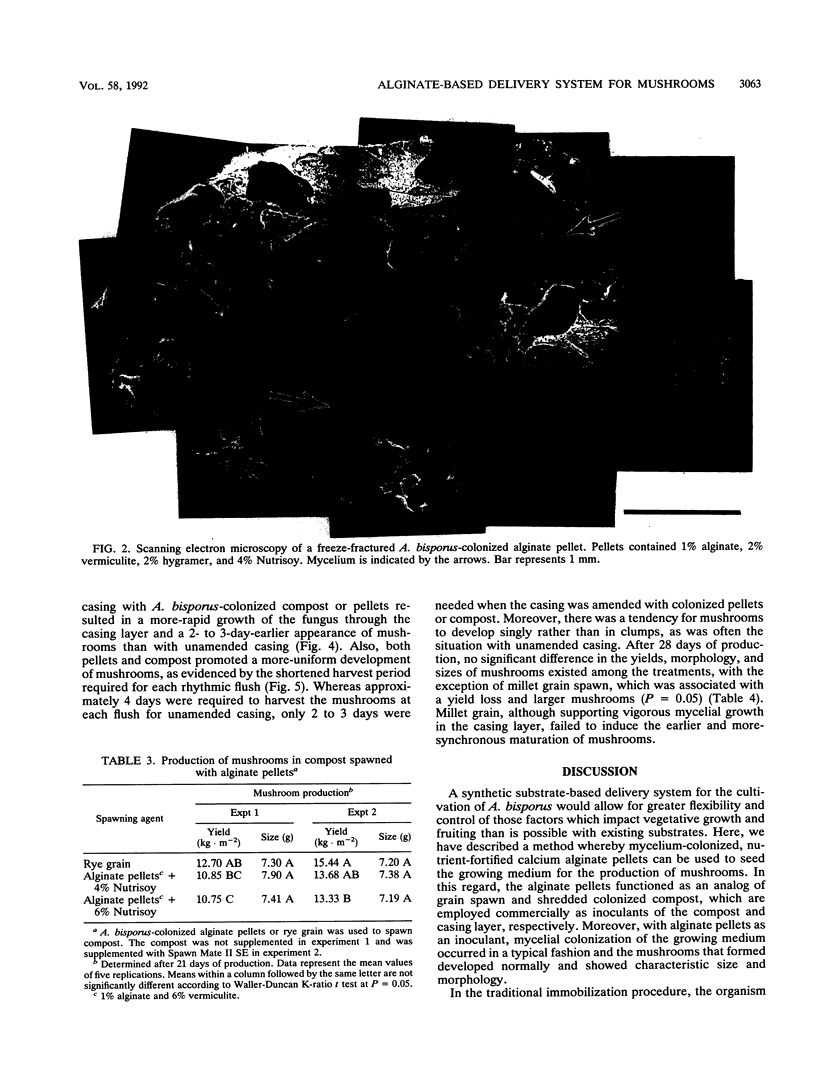

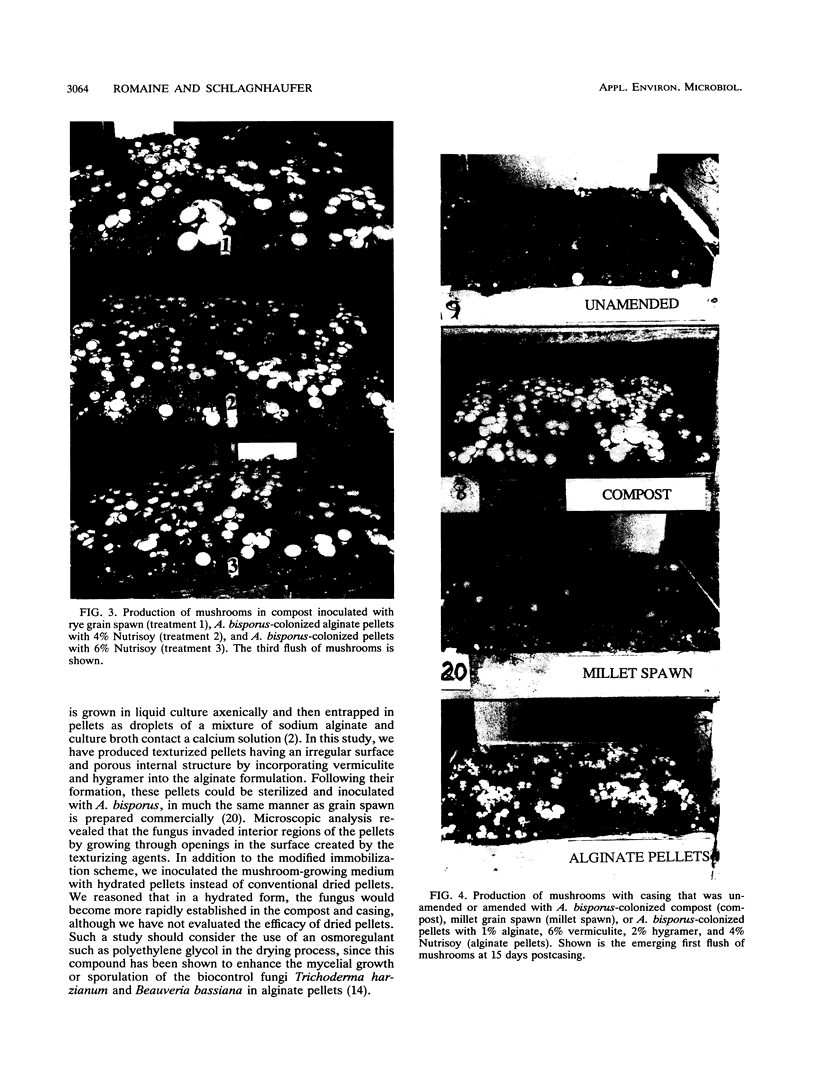

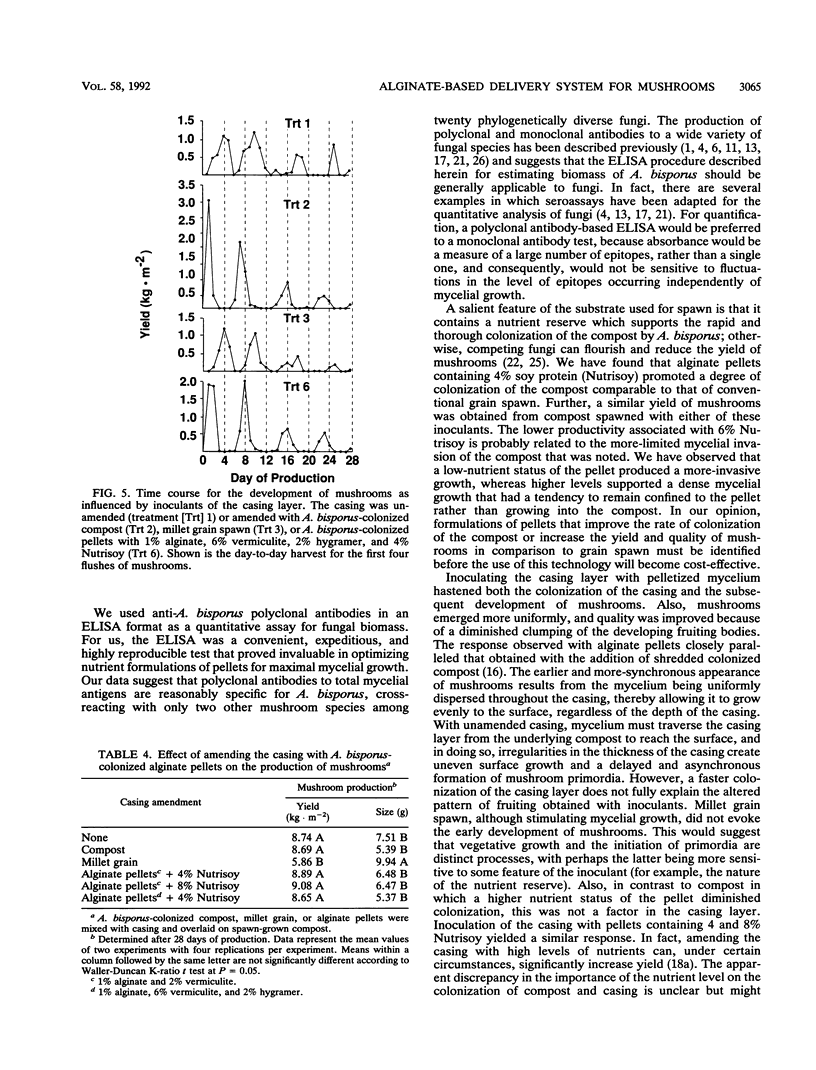

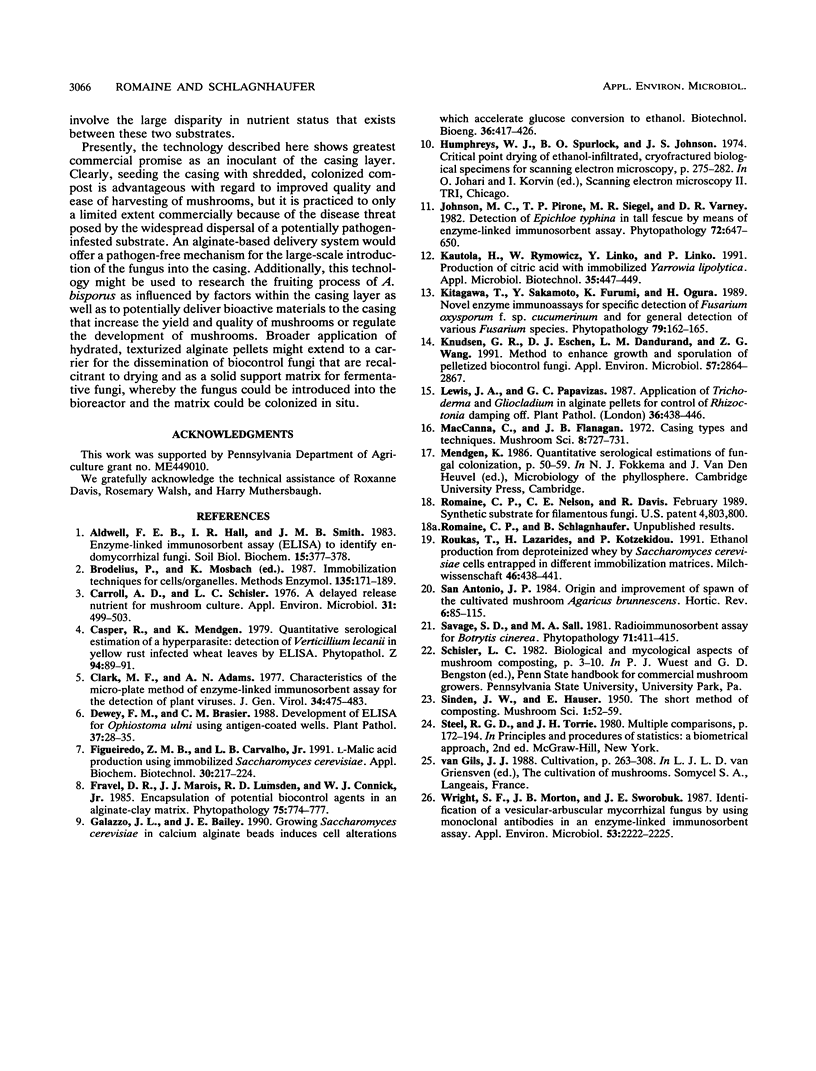

The production of the button mushroom Agaricus bisporus with mycelium-colonized alginate pellets as an inoculant of the growing medium was investigated. Pellets having an irregular surface and porous internal structure were prepared by complexing a mixture of 1% sodium alginate, 2 to 6% vermiculite, 2% hygramer, and various concentrations of Nutrisoy (soy protein) with calcium chloride. The porous structure allowed the pellets to be formed septically and then inoculated and colonized with the fungus following sterilization. By using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to estimate fungal biomass, the matrix components of the pellet were found to be of no nutritive value to A. bisporus. Pellets amended with Nutrisoy at a concentration of 0.5 to 8% supported extensive mycelial growth, as determined by significantly increased ELISA values, with a concentration of 4% being optimal and higher concentrations proving inhibitory. The addition of hydrated, mycelium-invaded pellets to the compost or casing layer supported the thorough colonization of the growing substrate and culminated in the formation of mushrooms that showed normal development and typical morphology. Yields and sizes of mushrooms were comparable from composts seeded with either colonized pellets or cereal grain spawn. Similarly, amending the casing layer with pelletized-mycelium-colonized compost resulted in a 2- to 3-day-earlier and more-synchronous emergence of mushrooms than with untreated casing. This technology shows the greatest potential as a pathogen-free inoculant of the casing layer in the commercial cultivation of mushrooms.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Carroll A. D., Schisler L. C. Delayed release nutrient supplement for mushroom culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976 Apr;31(4):499–503. doi: 10.1128/aem.31.4.499-503.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M. F., Adams A. N. Characteristics of the microplate method of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of plant viruses. J Gen Virol. 1977 Mar;34(3):475–483. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-34-3-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo Z. M., Carvalho Júnior L. B. L-malic acid production using immobilized Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1991 Aug;30(2):217–224. doi: 10.1007/BF02921688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen G. R., Eschen D. J., Dandurand L. M., Wang Z. G. Method to enhance growth and sporulation of pelletized biocontrol fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991 Oct;57(10):2864–2867. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.2864-2867.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. F., Morton J. B., Sworobuk J. E. Identification of a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus by using monoclonal antibodies in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Sep;53(9):2222–2225. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2222-2225.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]