Racial and socioeconomic disparities in morbidity and mortality have been apparent virtually as long as health statistics have been collected. In the United States, African Americans in particular fare worse than the majority population on nearly all measures of health, including infant mortality; life expectancy; cancer, heart disease, stroke, and trauma incidence and mortality; and self-rated health status.1 Individuals with low levels of educational attainment and income also tend to experience higher rates of illness and death, independent of race.2–4 Over the past several decades, though the U.S. population as a whole has enjoyed substantial declines in morbidity and mortality—largely due to better living conditions, public health measures, and advances in medical care—racial and socioeconomic disparities have persisted or even widened.1,5

Eliminating these disparities has become a national priority. It is 1 of the 2 primary objectives of the nation's public health agenda6 and is the central focus of the recently established National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities within the National Institutes of Health. Progress, however, has been slow. Most importantly, our understanding of the causes of health disparities remains limited. Race and socioeconomic status (SES) cannot themselves be thought of as causes. Both are composite concepts whose meanings are, in and of themselves, elusive. Race was originally formulated as a way of distinguishing human subpopulations with supposedly different genetic origins.7 Intermarriage and globalization and the findings of cross-national and genomic studies, however, have all diminished the likelihood that genetic differences account for the majority of the observed racial disparities in health. More likely, these disparities are due to social determinants.

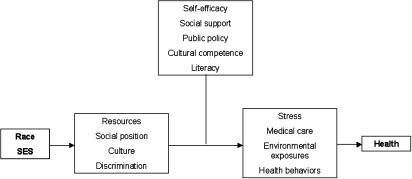

Race and SES are defining characteristics in our society. They segregate us into separate spheres and influence our opportunities and experiences. As such, they help determine our access to financial resources, our position in social hierarchies, the cultural lens through which we view the world, and the way we are treated by others (Fig. 1). Altering these aspects of race and SES will require major social and political change, which, in our incrementally oriented system, seems unlikely to occur in the near future. It is useful, then, to look at how these social implications of race and ethnicity affect health outcomes. A growing body of research suggests several “proximate” causes, i.e., those that directly result in differential morbidity and mortality: cumulative stress (or “allostatic load”), access to medical care, environmental exposures, and health behaviors.8,9 Reducing the impact of race and SES on these proximate causal factors may be the key to reducing and eliminating health disparities. It is critical, then, to understand the pathways between the root and proximate causes of health disparities. For instance, while it is fairly obvious how limited financial resources restrict access to medical care, it is less clear why race is associated with limited access independent of income and health insurance coverage. Likewise, how lower social position and greater social inequality contribute to psychological stress is not well understood. Some research has pointed to self-efficacy and locus of control as potentially important mediating factors.10 Social and community support may also play a role. Intuitively, a more “culturally competent” health care system and health and social policies aimed at greater social justice might improve matters as well.

Fig. 1.

Potential pathways mediating the effects of race and socioeconomic status on health

Several articles in this issue of JGIM suggest that enhancing health literacy may be another important pathway to reducing health disparities. Studying a population of community-dwelling elders, Sudore et al.11 found that low literacy was associated with higher mortality. They also found that African Americans, individuals with less than a high-school education, and people with low income had higher mortality and were much more likely than others to have low literacy. Although their analyses did not directly address whether accounting for literacy reduced the associations of race and SES with mortality, back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that African Americans with adequate literacy had mortality rates similar to whites. The same appears true for people with low education and income levels. In 2 other studies, Howard et al.12 and Sentell and Halpin13 directly examined low literacy as a possible mediator of health disparities. Both groups found that disparities in health status by both race and educational attainment were attenuated and in some cases eliminated after accounting for literacy. The robustness of all of these findings is amplified by the fact that the 3 studies included populations across a wide age range and each used a different instrument to measure literacy.

These findings raise the alluring possibility that improving literacy may be an effective mechanism to reduce health disparities. Alluring because low literacy may be remediable through simple interventions rather than radical social change. The promise of improving literacy as a means to reducing health disparities, however, depends on 2 important assumptions. The first assumption is that literacy is causally related to reduced disparities and not simply a marker of other causal pathways. Low literacy may cause health disparities through a variety of mechanisms. Low health literacy in particular, almost by definition, may reduce the accessibility and effectiveness of medical care, resulting in worse health outcomes. Interestingly, however, Sudore et al.11 found that accounting for access to care did not explain the effect of low literacy on mortality. Similarly, Howard et al. found that differences in literacy helped explain racial disparities in self-reported health status but not in vaccination rates. Moreover, other studies in this issue question the common assumption that low literacy contributes to poor medication adherence.14,15 In short, none of the studies support the notion that medical care mediates the association between literacy and health disparities. It should be noted, though, that in measuring facets of medical care, these studies may not have captured the more complex aspects of health system navigation, interpersonal negotiation, and illness management where literacy may have the greatest impact.

How else might literacy be related to health disparities? It is possible that by increasing the challenges of navigating through daily life, low literacy increases individuals' stress burden. It may also reduce the likelihood that individuals are adequately informed and activated with regard to healthy behaviors. Finally, low literacy may diminish an individual's self-efficacy, i.e., the ability to exert control over one's life and surroundings. Sudore et al.11 addressed most of these potential pathways by adjusting for variables intended to capture them and found that none of them helped explain the effect of literacy on mortality. Again, it is possible that the variables used were inadequate measures of stress, behaviors, and self-efficacy, but the findings still raise the question of whether literacy is causally related to health outcomes or is merely a marker for some other unmeasured factor.

The second assumption needed for the promise of improving literacy as a way to reduce health disparities to be realized is that the meaning and impact of literacy are similar across racial and socioeconomic groups. As discussed in the Perspective by Baker16 in this issue, literacy and the ways in which it affects health are complex. They are intricately linked to culture and language, facets of life that may vary widely among different racial and socioeconomic groups. It is possible, for instance, that some minority Americans with low literacy levels are less assimilated than others into mainstream (white) society and suffer poorer health due to higher stress levels from interracial conflict or anxiety or due to less engagement in mainstream health care institutions and practices. Intervening to improve the literacy levels of such individuals may have little or no effect on their health if they continue to feel culturally disengaged from the health care system or from people of other racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups.

Another important issue when considering literacy among different populations is that different aspects of literacy may be more or less relevant for different cultural groups. Most studies use individuals' capacity to read print materials as a proxy for the broader and more complex construct of literacy. In some cultures, oral communication may be much more important than written, and the ability to read may be less relevant to self-efficacy and health. It is notable that Mexican immigrants to the United States generally have better health profiles than white Americans, despite lower literacy levels in general, and much lower English-language literacy levels. Moreover, second- and third-generation Mexican Americans tend to be less healthy than their first-generation counterparts, despite greater English proficiency and presumably higher literacy levels.17 Clearly, literacy cannot be thought of as a “magic bullet.”

These caveats notwithstanding, the evidence that improving literacy may be an effective means to reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in health is sufficiently suggestive that interventions should be undertaken to test this hypothesis. Such trials will be the only way to definitively determine whether literacy is a mediator of racial and socioeconomic disparities in health or merely a marker of other causal factors. The most promising interventions will be among patients with complex chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, where literacy and its potential impact on self-efficacy and health behaviors are most likely to have a positive effect.18 Outcomes that could be feasibly measured in a reasonable time frame would include intermediate measures such as glycohemoglobin levels and blood pressure, as well as functional status and health-related quality of life. In designing interventions, it is critical to remember that improving health literacy can be achieved not only by affording new skills to patients but also by reducing the literacy demand, or complexity, of health-related information.

Health inequalities are among the most pressing concerns for our profession and for the nation as a whole. We still have much to learn about the pathways we might use to reduce and eventually eliminate these disparities. One such pathway, however, seems promising enough that it warrants investment of our efforts and funding. It is time for studies of improving literacy as a means to reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in health.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Saha is supported by an Advanced Research Career Development award from the Health Services Research & Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program. The ideas expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guralnik JM, Land KC, Blazer D, Fillenbaum GG, Branch LG. Educational status and active life expectancy among older blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:110–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie P, Rogot E, Anderson R, Johnson NJ, Backlund E. Black-white mortality differences by family income. Lancet. 1992;340:346–50. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schalick LM, Hadden WC, Pamuk E, Navarro V, Pappas G. The widening gap in death rates among income groups in the United States from 1967 to 1986. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30:13–26. doi: 10.2190/8QMH-4FAB-XAWP-VU95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witzig R. The medicalization of race: scientific legitimization of a flawed social construct. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:675–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:325–34. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosma H, Schrijvers C, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and importance of perceived control: cohort study. BMJ. 1999;319:1469–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sudore RL, Yaffe K, Satterfield S, et al. Limited literacy and mortality in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:806–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. The impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:857–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sentell TL, Halpin HA. The importance of adult literacy in understanding health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:862–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paasche-Orlow MK, Cheng DM, Palepu A, Meli S, Faber V, Samet JH. Health literacy, antiretroviral adherence, and HIV-RNA supression: a longitudinal perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:835–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang MD, Machtinger EL, Wang F, Schillinger D. Health literacy and anticoagulation-related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:841–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:878–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, Wang F, Adler N. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:245–54. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]