Abstract

BACKGROUND

Low literacy influences cervical cancer screening knowledge, and is a possible contributor to racial disparities in cervical cancer.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the hypothesis that literacy predicts patient adherence to follow-up recommendations after an abnormal Pap smear.

DESIGN

A prospective, continuity clinic-based study.

PARTICIPANTS

From a sample of 538 women undergoing literacy testing at the time of Pap smear screening, we studied 68 women with abnormal Pap smear diagnoses.

MEASUREMENTS

Literacy was assessed using the Rapid Evaluation of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM). We also measured other proxies for literacy, including educational attainment and physician estimates of patients' literacy level. Outcome measures included on-time and 1-year follow-up and duration of time to follow-up after an abnormal Pap smear.

RESULTS

Only one-third of the cohort adhered to follow-up recommendations. At 1 year, 25% of the women had not returned at all. Patients with inadequate literacy (as assessed by the REALM) were less likely to follow up within 1 year, although this result was not statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [OR]=3.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8 to 17.4). Patients subjectively assessed by their physician to have low literacy skills were significantly less likely to follow up within 1 year (adjusted OR=14, 95% CI: 3 to 65). Less than high school education (hazard ratio (HR)= 2.3; 95% CI: 1.2, 4.6) and low physician-estimated literacy level (HR=3.4, 95% CI: 1.4, 8.2), but not objective literacy level, were significant predictors of duration of time to follow-up, adjusting for recommended days to follow-up and other factors.

CONCLUSIONS

Among women with an abnormal Pap smear, those perceived by their physician to have low literacy were significantly more likely to fail to present for follow-up.

Keywords: literacy, Pap smear, cervical cancer, adherence, stereotype, disparities

Most of the deaths from cervical cancer in the United States occur among low-income and minority women, and most are avoidable.1 Low literacy is a potentially overlooked factor influencing cervical cancer screening behavior and has been recognized as a possible explanation for racial variations in the burden of this disease.2 For example, low literacy, rather than education or ethnicity, has been shown to predict cervical cancer screening knowledge significantly.3

While cervical cancer screening is one of the most widely used screening tests in the United States, the effectiveness of the test requires complex communication between patient and physician involving multiple points and kinds of contact with patients over time. Follow-up for an abnormal Pap smear requires several steps, many of which rely on patient literacy skills: (1) communication of the abnormal result from the provider to the patient (frequently via written letter, days to weeks following the patient's clinic visit), (2) arrangement for and communication about appropriate follow-up, (3) the patient's attendance at the follow-up appointment (sometimes in a different clinic and with a different provider), (4) agreement to proceed with additional testing and/or treatment (typically involving written informed consent documents), and (5) completion of the follow-up procedure. Unique to cervical cancer screening, the challenge of communication also involves vague language (e.g., “Pap smear” has no lay meaning), reference to a remote body part (many women are unfamiliar with the location of the cervix or its distinction from other gynecologic anatomy), and confusion about whether the Pap smear is a screening test or a therapeutic procedure.3,4

Despite the complex types of communication necessary to execute follow-up procedures, physician-patient encounters rarely involve formal determination of the patient's communication or literacy skills. Rather, proxy estimates (such as charting of the patient's education level) or informal judgments (such as provider intuition) may be used. When an abnormal Pap result returns, the effectiveness of the screening test in preventing cervical cancer is entirely dependent on the quality of follow-up; in the absence of follow-up, the test becomes useless.

Adherence to follow-up after an abnormal screening test represents a plausible, yet insufficiently explored, mechanism through which low literacy may influence health disparities. We have followed women with abnormal Pap smears for 1 year, providing longitudinal data to address the hypothesis that literacy predicts adherence to follow-up recommendations after cervical cancer screening.

METHODS

Sample

Between January and December 1999, all women who presented to the ambulatory primary care and HIV ob/gyn continuity of care clinics at a Chicago academic medical center were eligible for enrollment. Self-identified English-speaking patients were privately approached during registration at the clinic by 1 of 6 trained, nonphysician, female interviewers. In this large convenience sample, enrollment was sequential, according to patient presentation. Women younger than 18 years old were excluded. Of the 601 patients approached at the clinics, 538 agreed to participate, 30 refused, 17 were ineligible because of age, and 16 had missing data. Hence, the participation rate of those eligible was 90%. A detailed description of the sample can be found in Lindau et al.3 Nine additional women are included here in the total participation rate as compared with the sample reported in 2002, due to resolution of missing data. The study consent form was affixed to the medical chart to prevent repeat enrollment. While comparable data about clinic attendees not approached for the study are unavailable, interviewer schedules rotated to maximize coverage at each clinic site and on each clinic day. The investigation protocol and consent procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Patient Interview and Objective Health Literacy Assessment

All interviews were conducted before the physician encounter. Women participated in a 10-minute interview ascertaining demographics, cervical cancer screening and health practice history, knowledge related to cervical cancer screening and prevention, and perception of previous patient-physician interaction about cervical cancer screening. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)5 was used to determine an objective health literacy score. Recommended for use by the National Work Group on Literacy and Health,5,6 the REALM is a reading recognition test composed of 66 health-related words. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine scores are typically used to estimate literacy level as follows: 0 to 18, ≤3rd grade; 19 to 44, 4th to 6th grade; 45 to 60, 7th to 8th grade; and 61 to 66, ≥9th grade.5 We further classified literacy level as adequate (REALM ≥61 or high school level) or inadequate.

Physician Self-administered Questionnaire: Subjective and Proxy Measures of Literacy

Immediately after the patient visit, a brief, anonymous self-administered questionnaire was filled out by physicians (32 residents rotating through post graduate years 2 to 4, approximately 3/4 of whom were female) to ascertain physician perceptions of patient literacy level. Patients were assigned to each physician by administrative staff at the time of scheduling and remained with a given physician throughout the physician's period of training to maximize continuity of care. Physicians were asked “Based on your interaction today, what is your estimate of your patient's reading level?” Response categories included high school, 7th to 8th grade, 4th to 6th sixth grade, 3rd grade, or below, with higher scores indicating a higher reading level. In multivariate analyses, physicians' subjective literacy assessment was dichotomized as adequate (high school level or above) or inadequate (below high school). Physicians neither received formal introduction to the study nor training in literacy evaluation. Physicians were also asked to predict the likelihood of patient follow-up (on-time vs not on-time).

Recommendations for Follow-up

The study did not dictate physician recommendations for follow-up, which vary by patient health status, age, and medical history. Common practice for these clinics was to recommend follow-up as soon as possible for cancer, carcinoma in situ (CIS), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL), and atypical glandular cells (AGUS). For most patients with low-grade squamous dysplasia, follow-up was recommended within 3 months. For those with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) or insufficient sample, follow-up recommendations typically allowed for return within 6 months (this study was conducted before widespread use of human papillomavirus testing, which is now used to triage follow-up for ASCUS). Patients with HIV or a history of abnormal Pap smear would have likely been instructed to return sooner than those without these diagnoses. The results were typically communicated to patient first via phone call and then via a variety of methods including repeat phone call, letter, and reminders at subsequent clinic visits scheduled for other reasons.

Chart Abstraction

Chart abstraction was used to clarify demographic and medical information obtained in the interview, and to determine Pap test results, physician recommendations for follow-up, method of patient contact, and follow-up adherence over 1 year following the index Pap test. A follow-up visit was defined as one where either a Pap smear was repeated, colposcopy was performed, or a procedure to treat a cervical lesion occurred. Research staff conducting chart abstraction were unaware of the participants' literacy score.

Analysis

SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and STATA version 8.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) were used for data analysis. The sociodemographic characteristics of patients who required follow-up visits were compared by literacy levels (REALM-based), using Fisher's exact tests.

Three sets of analyses were performed to determine the relationship between literacy and follow-up adherence. Within each set of analyses, separate models were run for each of the following predictor variables: (1) objective literacy level as measured by the REALM, (2) physician's subjective assessment of literacy level, (3) educational level (i.e., high school graduation status), and (4) physician's prediction of on-time follow-up. All models controlled for age, race, diagnosis of cancer or HIV, employment status, and private insurance status. Insurance status was not used as a covariate in models with physician assessment of literacy level due to substantial correlation between them.

In the first set of analyses, logistic regression was used to determine predictors of on-time patient follow-up, dichotomized as “on-time” (follow-up visit on or before the recommended date derived from the physician's recommendation in the medical record) and “not on-time.”

Second, logistic regression was used to determine predictors of patient follow-up, dichotomized as ever (within 365 days of the index Pap) and never. The 365-day cutoff was used because standard practice in the clinical setting at that time was to recommend screening at a maximum of 1-year intervals. The 365-day cutoff, then, is analytically necessary, as a clinic visit occurring after 365 days may indicate either a follow-up or an annual screening visit.

The third set of analyses examined predictors of the duration of time to follow-up, using Cox proportional hazards regression. Time to follow-up was defined as the time between the abnormal Pap smear diagnosis and the actual follow-up date. A visit was defined as a follow-up visit if it occurred within 1 year of the date of the initial abnormal Pap smear. Subjects not returning for a follow-up visit within 1 year were censored at 365 days. The recommended days to follow-up variable was used as an additional covariate in this adjusted duration analysis to control for heterogeneity in the recommended time to follow-up among these patients. Cox regressions determined the hazard rate of follow-up time, where the hazard rate in this context is defined as the “risk” of follow-up on the next day given that follow-up has not occurred as of the present time. Because the event of interest in this survival analysis is the follow-up visit (which is a good outcome), a hazard ratio of greater than 1 implies an increased likelihood of early return; thus, it is desirable to have a larger hazard ratio.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis

Seventy-five women required follow-up as a result of an abnormal Pap test. Sixty-eight of these women had complete data on all outcomes and covariates and form our primary analysis sample. Physician predictions of literacy and on-time follow-up behavior were obtained for 56 patients. Based on exact χ2 tests, patients for whom physician predictions were missing did not differ significantly in terms of adequate literacy (P=.32), high school graduation (P=.32), REALM score (P=.81), HIV status (P=.99), cancer status (P=.12), or recommended days to follow-up (P=.27).

The most common indications for follow-up were ASCUS (34%) or mild dysplasia (low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [LGSIL]) (45%) (Table 1). Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions was more common among women with adequate literacy (50% vs 29%, P=.13). The majority of medical charts documented contact about Pap smear results via telephone alone or in combination with another contact method (e.g., letter); women contacted by phone did not differ by literacy level from those contacted using another method. However, data on contact method were missing for 27% of the sample.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among Women with Abnormal Pap Smear, by Literacy Level.

| Adequate Lteracy (n=44, 65%) | Inadequate literacy (n=24, 35%) | P Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age (y) | |||||

| 18 to 24 | 15 | 34 | 12 | 46 | .74 |

| 25 to 30 | 11 | 25 | 4 | 17 | |

| 31 to 39 | 12 | 27 | 5 | 20 | |

| 40 to 49 | 6 | 14 | 4 | 17 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| African American/black | 23 | 52 | 16 | 67 | .16 |

| Hispanic | 9 | 21 | 7 | 29 | |

| White | 8 | 18 | 1 | 4 | |

| Other/unknown | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Native language | |||||

| English | 38 | 85 | 21 | 88 | .77 |

| Spanish | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| English/Spanish | 2 | 5 | 2 | 8 | |

| Other | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Insurance status | |||||

| Medicaid | 28 | 64 | 22 | 92 | .04 |

| Private | 12 | 27 | 2 | 8 | |

| Self-pay/no insurance | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| HIV status† | |||||

| No | 28 | 64 | 18 | 75 | .45 |

| Yes | 16 | 36 | 6 | 25 | |

| Employment | |||||

| No | 22 | 50 | 15 | 63 | .55 |

| Yes | 17 | 39 | 8 | 33 | |

| Student | 5 | 11 | 1 | 4 | |

| Reason for follow-up | |||||

| ASCUS | 11 | 25 | 13 | 55 | .20 |

| LGSIL | 22 | 50 | 7 | 29 | |

| HGSIL‡ | 3 | 7 | 2 | 8 | |

| CIS/Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| AGUS | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other§ | 6 | 14 | 2 | 8 | |

All comparisons were based on Fisher's exact test.

All HIV+ patients were seen in the HIV ob/gyn continuity of care clinic; all HIV− patients were seen in the general ob/gyn continuity of care clinics.

One HGSIL case also diagnosed with AGUS.

Includes absence of endocervical cells, presence of endometrial cells, and unsatisfactory specimen.

AGUS, atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance; HGSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; CIS, carcinoma in situ; ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; LGSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Table 1 shows bivariate comparisons of sociodemographic characteristics by literacy level. Women with adequate literacy did not differ significantly from those with inadequate literacy in terms of age, ethnicity, native language, employment status, HIV status and clinic type, or the indication for follow-up. Those with adequate literacy, however, were more likely to be privately insured.

Table 2 shows the bivariate associations of objective literacy (REALM-based) with subjective literacy (physician assessment), education level, and physician predictions of patient follow-up adherence. High school graduation (P=.29) was not significantly associated with objective literacy level. Physicians' predictions of on-time follow-up and physician subjective assessment were significantly associated with objective literacy level. There was a high level of agreement between physicians' subjective assessment and objective literacy level (κ=0.43, P=.0006).

Table 2. Literacy, Education, and Physician Assessments of Women with Abnormal Pap Smear.

| Adequate Literacy (n=44, 65%) | Inadequate Literacy (n=24, 35%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REALM score, mean (SD) | 64.0 (1.5) | 45.5 (13.9) | <.0001 |

| High school graduate, n (%) | |||

| No | 26 (57) | 18 (77) | .28 |

| Yes | 18 (43) | 6 (23) | |

| Physician assessment of literacy level, n (%)* | |||

| Below high school | 10 (26) | 13 (72) | .002 |

| High school or above | 28 (74) | 5 (28) | |

| Physician prediction of on-time follow-up, n (%)* | |||

| Not on time | 16 (42) | 15 (83) | .004 |

| On time | 22 (58) | 3 (17) |

N=56.

REALM, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine.

Predictors of Adherence to Follow-Up Recommendations: On-Time Follow-up and Follow-Up Within 1 Year

Only 24 women (35%) followed up on time after an abnormal Pap smear diagnosis, while 51 (75%) followed up within 1 year of the visit at which an abnormal Pap smear was obtained. Recommended days to follow-up did not vary by objective or subjective assessments of literacy. Only subjective literacy had a significant positive association with follow-up within 1 year (Table 3). In unadjusted analyses, literacy was not associated with either on-time or 1-year follow-up (Table 4). In the logistic models, adherence to follow-up recommendations did not significantly differ by objective or subjective literacy level, education, or physician prediction of on-time follow-up; however, physicians' subjective assessment of patient literacy showed the strongest association (Table 4). Likewise, physicians' subjective assessment of literacy was a significant predictor of follow-up within 1 year, before and after adjusting for covariates (Table 4). In the adjusted analysis, high school graduation and physicians' subjective assessment of patient literacy skills were significant predictors of patients' returning within 1 year. Objective literacy score was a weaker and nonsignificant predictor of follow-up within 1 year.

Table 3. Recommended and Actual Follow-up for Abnormal Pap Smear, by Literacy Level.

| Objective Literacy (REALM-based) | P Value | Subjective Literacy (Physician Assessments) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate (n=44, 65%) | Inadequate (n=24, 35%) | Adequate (n=33, 59%) | Inadequate (n=23, 41%) | |||

| Recommended days to follow-up, mean (SD) | 89.3 (53.4) | 87.6 (62.0) | .99 | 87.8 (62.4) | 82.2 (57.7) | .73 |

| Patient followed up on time, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 29 (66) | 16 (67) | .99 | 20 (61) | 17 (74) | .40 |

| Yes | 16 (34) | 8 (33) | 13 (39) | 6 (26) | ||

| Patient followed up within 1 year, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 9 (20) | 8 (33) | .25 | 4 (12) | 11 (48) | .005 |

| Yes | 35 (80) | 16 (67) | 29 (88) | 12 (52) | ||

| Days to follow-up, n (%)* | ||||||

| 0 to 60 days | 9 (26) | 5 (31) | .41 | 9 (31) | 3 (25) | .15 |

| 61 to 120 days | 9 (26) | 1 (7) | 6 (21) | 3 (25) | ||

| 121 to 180 days | 7 (20) | 5 (31) | 2 (7) | 4 (33) | ||

| 181 to 365 days | 10 (28) | 5 (31) | 12 (41) | 2 (17) | ||

P values based on t test for recommended days to follow-up and Fisher's exact tests otherwise.

Among those who returned within 1 year.

Table 4. Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Literacy, Education, and Physician Assessments with On-time and 1-Year Follow-up for Abnormal Pap Smear.

| OR 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|

| On-time Follow-up | Follow-up Within a Year | |

| Adequate literacy (REALM based) (N=68) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.03 (0.36, 2.99) | 1.94 (0.62, 6.09) |

| Adjusted* | 2.05 (0.47, 8.85) | 3.75 (0.81, 17.4) |

| High school graduation (N=68) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.53 (0.17, 1.63) | 2.10 (0.59, 7.51) |

| Adjusted* | 1.32 (0.32, 5.52) | 3.84 (1.01, 14.6) |

| Physician subjective assessment of adequate literacy (N=56) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.84 (0.56, 6.03) | 6.65 (1.55, 28.6) |

| Adjusted* | 2.42 (0.59, 9.86) | 13.6 (2.9, 64.9) |

| Physician prediction of on-time follow-up (N=56) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.62 (0.19, 1.95) | 0.62 (0.19, 2.07) |

| Adjusted* | 1.06 (0.27, 4.20) | 0.54 (0.11, 2.71) |

Adjusted for age, HIV status, cancer, race, unemployment status, insurance status. Insurance status was not used as a covariate for physician assessment of literacy level.

REALM, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine.

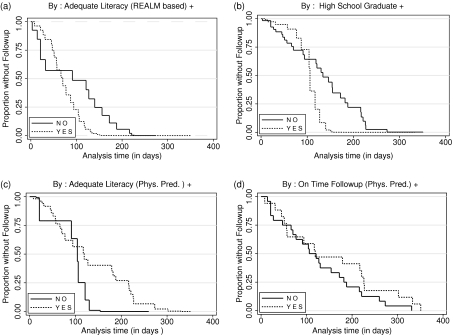

Duration Analysis: Predictors of Time to Follow-Up

The duration analyses examined patterns of follow-up among women with abnormal Pap smear diagnosis, adjusted for patient characteristics and recommended days to follow-up (Fig. 1). High school graduation (hazard ratio [HR]=2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2, 4.6) and physicians' subjective assessment of patient literacy skills (HR=3.4, 95% CI: 1.4, 8.2) were significant predictors of duration to follow-up.

FIGURE 1.

Time to follow-up for abnormal Pap smear, by literacy levels. Adjusted for age, race, diagnosis of cancer or HIV, employment status, private insurance, and recommended days to follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we showed that in a large, multiethnic cohort of women, health literacy was an important predictor of knowledge about cervical cancer screening.3 This study examined 68 women with abnormal Pap smears to determine whether literacy would predict adherence to follow-up recommendations after cervical cancer screening. Because formal measurement of health literacy rarely occurs in the clinical setting, we also tested the predictive value of proxy measures, including physician subjective assessment of patient literacy level and patient education level. We also directly asked physicians to predict whether the patient would return for follow-up on time.

In determining whether objective or subjective measures of literacy would predict on-time follow-up for an abnormal Pap smear, we found none to be statistically significant. However, physician subjective assessment of literacy was the strongest predictor. Only one third of the cohort adhered to follow-up recommendations for an abnormal Pap smear. At 1 year, 25% of the women had not returned at all. Patients with inadequate literacy (REALM based) were less likely to follow up within 1 year, although this finding did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, the odds of failed follow-up among patients subjectively assessed to have low literacy skills by their physician were 13 times that of patients perceived to have adequate literacy. Among those who did follow up, less than high school education and low subjective literacy level, but not objective literacy level, were significant predictors of delay. Interestingly, physician prediction of patient follow-up adherence was not a useful predictor of any of the follow-up measures.

This study adds to a growing number of investigations that implicate low literacy as a correlate of negative health behaviors7,8 and a cause of poor health outcomes.9,10 In the context of general medical care, it has been suggested that literacy testing should and can occur routinely in the clinic11–13 and that this strategy is acceptable to patients and physicians.14 The generalizability of these findings to ob/gyn practice needs further investigation. For example, in the course of data collection for this study, we found that the REALM test required debriefing to alleviate participant discomfort. As a result, we amended our protocol to give oral reassurance following the REALM and to give participants an opportunity to ask questions about words they were unable to read or comprehend. In addition, the more highly invasive physical examination, accompanied, perhaps, by heightened patient experience of vulnerability or anxiety in the ob/gyn setting, may make literacy testing less acceptable or feasible. This study explores possible alternatives to testing patient literacy that may assist physicians or other health care providers in incorporating patient literacy level into clinical counseling and decision making.

While our findings warrant further investigation, they suggest 2 potential strategies for predicting patient follow-up adherence after an abnormal Pap smear, neither of which requires additional testing. Physician perception of patient literacy level, rather than tested literacy or the physician perception of whether a patient will follow up, was a very strong and significant predictor of whether and when a patient actually returned for care. If the physician subjectively rates the patient as having a less than high school reading level, then concern might be raised and interventions put in place to promote follow-up adherence.15

The dynamics of how physicians formulate perceptions about patient literacy skills or what other patient characteristics are incorporated in forming this subjective assessment (e.g., factors not accounted for in this analysis such as tobacco use, sexual behavior, body language, or communication) remain to be identified. Evidence exists that sociodemographic characteristics of patients do influence physician interactions, diagnosis, and treatment.16 While engagement of physician intuition may facilitate the use of targeted strategies at the screening visit to maximize individual patient follow-up, over-reliance on physician intuition may encourage stereotyping with negative consequences. Studies designed to test such a strategy, and related interventions, are needed.

We also showed that high school education level was a significant predictor of duration of time to follow-up. It may be that, unlike the other predictors, high school education best captures the individual's ability to control her time and availability and/or to negotiate a prompt clinic appointment, allowing her to return for care sooner, rather than later. A post hoc multivariate analysis including both physician subjective assessment of patient literacy skills and patient education level indicated that each retained its significant effect as an independent predictor of patient adherence behavior (HR=3.2, 95% CI:1.3 to 7.6 and HR=2.4, 95% CI:1.1 to 5.0, respectively). Frequently, patient education history is charted as part of routine clinical care. The effect of integrating this simple, individual-level information into the strategy for communication, counseling, and scheduling to maximize prompt return should also be further investigated.

The generalizability of our findings may be limited by the ob/gyn setting, the study of only resident physicians, and the fact that patients were recruited from clinic settings predominantly serving disadvantaged populations. More experienced physicians may have a more intuitive awareness of patient's reading levels or likelihood of follow-up. Alternatively, resident physicians working in an urban, continuity-of-care setting may have more sensitivity to and current experience identifying the needs of underserved patients.

Individual physician characteristics may also play an important role in patient follow-up behavior. Because our physician surveys were anonymous, and our Pap smear cytology reports listed the attending rather than the resident physician, we were unable to account for clustering of patients among individual physicians. However, we expect any effect of correlated data to be small in this study, due to the likely uniform distribution of 68 patients over 32 physicians. Another limitation of the study is its reliance on chart review for assessment of adherence to follow-up recommendations. About 25% of charts revealed missing data on notification attempts. Additionally, we were unable to determine patients' explanations for delayed or failed return or whether patients who never returned received follow-up care elsewhere.

Disparities in cervical cancer diagnosis and survival in the United States have been attributed primarily to socioeconomic mechanisms such as poverty, lack of insurance, and access to public versus private venues of care.17 Other factors, such as differences in tobacco use and sexual behavior, have also been implicated.18,19 Our study suggests that physician assessment of patient literacy skills and knowledge of patient education level may serve as important tools for identifying patients at risk for inadequate follow-up for an abnormal Pap smear. Further research, perhaps using qualitative study of patient-physician interactions, may seek to decipher the cues physicians use to make these informal judgments. This could be an important next step in understanding how to reduce disparities in the incidence and burden of cervical cancer in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ellen King and Karl Mendoza for their assistance in preparing the manuscript. We would also like to thank the reviewers, particularly the statistical consultant, for thoughtful and careful feedback.

Funding: The research for this paper was funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (RWJF Grant #038905) and a grant from Northwestern Memorial Foundation Intramural Research Grants Program. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marcus AC, Crane LA. A review of cervical cancer screening intervention research: implications for public health programs and future research. Prev Med. 1998;27:13–31. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindau ST, Tomori C, McCarville MA, Bennett CL. Improving rates of cervical cancer screening and Pap smear follow-up for lo-income women with limited health literacy. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:316–23. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100102558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindau ST, Tomori C, Lyons T, Langseth L, Bennett CL, Garcia P. The association of health literacy with cervical cancer prevention knowledge and health behaviors in a multiethnic cohort of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:938–43. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mays RM, Zimet GD, Winston Y, Kee R, Dickes J, Su L. Human papillomavirus, genital warts, Pap smears, and cervical cancer: knowledge and beliefs of adolescent and adult women. Health Care Women Int. 2000;21:361–74. doi: 10.1080/07399330050082218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous. Communicating with patients who have limited literacy skills: consensus statement from the National Work Group on Literacy and Health. J Fam Pract. 1998;27:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalichman SC, Benotsch E, Suarez T, Catz S, Miller J, Rompa D. Health literacy and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:325–31. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkman N, DeWalt D, Pignone M, et al. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Literacy and health outcomes. evidence report/technology assessment no. 87. 2004 January. Report No.: AHRQ Publication No. 04-E007-2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bass PF, III, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1036–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.10651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bass PF, III, Wilson JF, Griffith CH, Barnett DR. Residents' ability to identify patients with poor literacy skills. Acad Med. 2002;77:1039–41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayeaux EJ, Murphy PW, Arnold C, Davis TC, Jackson RH, Sentell T. Improving patient education for patients with low literacy skills. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53:205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligman H, Wang F, Palacios J, et al. Physician notification of their diabetes patients' limited health literacy. A randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1001–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safeer RS, Keenan J. Health literacy: the gap between physicians and patients. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:463–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–28. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Health care disparities and cervical cancer. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2098–103. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitt M, Devesa S, Breen N. Papanicolaou test use among reproductive-age women at high risk for cervical cancer: analyses of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:666–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plummer M, Herrero R, Franceschi S, et al. Smoking and cervical cancer: pooled analysis of the IARC multi-centric case–control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:805–14. doi: 10.1023/b:caco.0000003811.98261.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]