Abstract

BACKGROUND

Individuals with limited literacy and those with depression share many characteristics, including low self-esteem, feelings of worthlessness, and shame.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether literacy education, provided along with standard depression treatment to adults with depression and limited literacy, would result in greater improvement in depression than would standard depression treatment alone.

DESIGN

Randomized clinical trial with patients assigned either to an intervention group that received standard depression treatment plus literacy education, or a control group that received only standard depression treatment.

PARTICIPANTS

Seventy adult patients of a community health center who tested positive for depression using the 9-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and had limited literacy based on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).

MEASUREMENTS

Depression severity was assessed with PHQ-9 scores at baseline and at 3 follow-up evaluations that took place up to 1 year after study enrollment. Changes in PHQ-9 scores between baseline and follow-up evaluations were compared between the intervention and control groups.

RESULTS

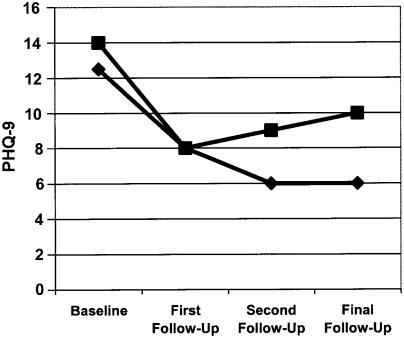

The median PHQ-9 scores were similar in both the intervention and control groups at baseline (12.5 and 14, respectively). Nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire scores improved in both groups, but the improvement was significantly larger in the intervention group. The final follow-up PHQ-9 scores declined to 6 in the intervention group but only to 10 in the control group.

CONCLUSIONS

There may be benefit to assessing the literacy skills of patients who are depressed, and recommending that patients with both depression and limited literacy consider enrolling in adult education classes as an adjuvant treatment for depression.

Keywords: literacy, depression, education

Limited literacy is common among adults in the United States. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), conducted in 2003 by the U.S. Department of Education,1 between 40% and 50% of American adults have only very basic or below basic literacy skills, making it difficult for them to function on the job and in society. The problem of limited literacy is pervasive. It involves individuals of all backgrounds, races, and socioeconomic classes. In some segments of the population, such as certain ethnic minority groups and the elderly, the rate of limited literacy may exceed 75%.1–4

Research has demonstrated that limited literacy is associated with poorer health outcomes and lower health status.5–9 But, as pointed out in a report on health literacy from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research,10 there is little evidence that improving literacy skills can improve an individual's health. Indeed, to our knowledge, no research in an industrialized nation has ever demonstrated that enhancing literacy skills can actually cause someone to “get better” from an illness or chronic condition.

The study reported here is a preliminary investigation of whether improving literacy skills can improve a specific health outcome—severity of depression—in a cohort of depressed individuals with limited literacy skills in the United States.

We focused on depression for 2 reasons. First, depression is common. Some 30 million Americans are thought to have depression, and at least 1 in 6 Americans experiences an episode of major depression at some point.11–13 Second, people with limited literacy skills and those who are depressed share several characteristics. Specifically, people with limited literacy and individuals with depression both report low self-esteem, feelings of worthlessness, poor self-efficacy, an external locus of control, and experiencing guilt or shame over their limitations.14–20 In fact, some of these characteristics, like worthlessness and guilt, are not only common in both limited health literacy and depression, they are also defining characteristics of depression in the fourth edn of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV).21

Because of the characteristics shared between limited literacy and depression, we hypothesized that literacy education, provided along with standard depression treatments to adults with depression and limited health literacy skills, would result in a greater improvement in depression symptoms than would standard depression treatments alone. This paper reports the results of a preliminary investigation designed to test that hypothesis.

METHODS

Overview

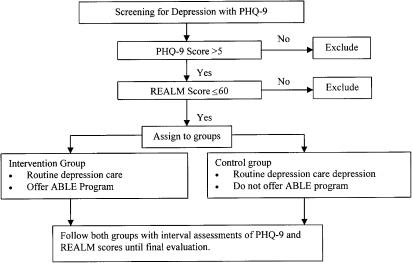

This was a randomized controlled trial in which patients with both limited literacy and depression were assigned to 1 of 2 treatment groups. Patients in the control group received standard treatments for depression prescribed by their primary care clinician (family physician, physician assistant, or advanced-practice nurse). Patients in the intervention group received the same standard treatments for depression, but they were also referred for literacy training at an adult education program. Figure 1 illustrates the study protocol.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study enrollment and follow-up. PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire; REALM, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine.

Setting

This research was conducted in a community health center that serves a predominantly poor clientele. The community's Adult Basic and Literacy Education (ABLE) program is housed on-site at the health center. The study methods were reviewed and approved by the center's institutional review board.

Subject Enrollment

Eligibility Requirements.

Patients were eligible for participation in the study if they scored positive for depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)22 and if they had limited literacy skills when tested with the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).23 Both of these instruments are described below. Additional eligibility requirements included age ≥18 years; ability to communicate and converse meaningfully with project staff in English; not currently under treatment for depression; no diagnosis of dementia or other neuropsychiatric disorder; and presentation to the health center for something other than an acute life-threatening emergency.

PHQ-9.

All patients seen at the health center were routinely screened for depression with the PHQ-9 using the protocol specified by the Health Disparities Collaborative, a national collaborative involving the US Bureau of Primary Care, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the National Association of Community Health Centers.24 The PHQ-9 is a widely used depression detection instrument based on DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis of depression.22,25 It has also been used successfully to monitor outcomes of depression treatment.26 Because the study involved patients with limited literacy, study personnel read the PHQ-9 questions to subjects.

The PHQ-9 asks subjects to rate the frequency of DSM-IV depression criteria from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively. A score ≥5 has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 73% for a diagnosis of depressive disorder.22 Patients seen at the community health center who had a PHQ-9 score ≥5, the cutoff level recommended by the Collaborative for considering the diagnosis of depression at the time our study began, next underwent assessment of their literacy skills.

REALM

The REALM is a psychometrically reliable and valid literacy assessment instrument that can be completed in about 2 minutes.23 Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine is a word-recognition test, in which subjects read from a list of 66 medical words arranged in order of complexity and pronunciation difficulty. Patients are asked to read aloud as many words as they can, beginning with the first word and continuing through the list as far as they can.

The REALM scores of 0 to 18 indicate a third-grade reading level or lower, 19 to 44 indicate a fourth to sixth-grade reading level, 45 to 60 indicate a seventh to eighth-grade level, and 61 to 66 indicate a high school reading level or above. In our study, patients whose score indicated literacy skills at or below the eighth-grade level (i.e., score ≤60) were eligible for participation.

Randomization

After giving informed consent, patients with a PHQ-9 score >5 (indicating depression) and a REALM score ≤60 (indicating limited literacy) were randomized to either a control group or an intervention group. Randomization was performed with computer-generated random numbers. The control group received routine depression care, as described below. The intervention group received the same routine depression care, plus referral to the ABLE program for literacy education.

At the time of randomization, we collected demographic information on each subject. This information included age, gender, ethnic group, medical insurance status, and occupation.

Interventions

Depression Care

Routine depression care for patients in both the control and intervention groups was provided by their primary care clinician at the community health center. This care was delivered according to a protocol specified by the Health Disparities Collaborative mentioned earlier.24 Briefly, the treatment involved either prescription of antidepressant medications or provision of counseling, with the choice made by the patient's primary care clinician. Counseling methods specified in the protocol included cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving treatment.

Literacy Skill Enhancement

Literacy skill enhancement was provided through the ABLE program. Patients referred to the program were first interviewed by an adult education teacher to determine the patient's learning style, educational history, and individual academic strengths and weaknesses.

Following the interview, an assessment with the Tests of Adult Basic Education27 was conducted to determine baseline skill levels. Clients with very low baseline skills were also assessed with other instruments. Those whose reading skills were scored below the sixth-grade level with any of the instruments underwent additional evaluation with PowerPath,28 a computer-based assessment that screens for learning disabilities. Such disabilities were taken into consideration as learning plans were developed.

After the aforementioned assessments, the ABLE teacher and patient discussed personal and educational goals and developed a learning plan. Learning was facilitated through computer-assisted instruction, traditional text-based instruction, and/or self-paced learning modules. Patients attended as many sessions as they wished, and could choose to work individually, in small groups, or with one-on-one tutors; most students opted to participate to some extent in all of these educational modalities. The program also offered employment-skill training that involved assistance with preparation of resumes and job applications, and practice and advice about job interviews.

Outcome Measures

Patients in both groups underwent interval assessments of depression severity using the PHQ-9. These assessments were conducted for as long as the patient remained in the study up to a maximum of 12 months. The first follow-up assessment was performed between 1 and 3 months after entry into the study, the second between 3 and 6 months after entry, and the final follow-up between 6 and 12 months. Nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire assessments were performed by a study coordinator who was not involved with or aware of the nature of the patients' depression treatment. For patients in the intervention group, each of the interval assessments also included administration of the REALM.

After the final follow-up visit, we performed a review of medical records to determine depression treatments received by each patient. We noted the percentage of patients treated with antidepressant medication and the percentage who underwent counseling.

Data Analysis

Subjects randomized to the intervention group were included and analyzed in that group, regardless of whether they actually participated in ABLE classes. Although we present data for the first, second, and final follow-up evaluation, the key dependent variable in our analysis was depression severity measured with the PHQ-9 at the final evaluation.

For subjects who presented for evaluation more than once between 6 and 12 months (43% of subjects presented twice), we only considered PHQ-9 scores from the second of these evaluations. For the 34% of subjects whose final evaluation occurred at the second follow-up visit, we used PHQ-9 scores from that visit in the final analysis (last observation carried forward).29 We excluded subjects from the final analysis if they did not participate past the first follow-up visit at 1 and 3 months.

Because PHQ-9 scores were not normally distributed, we used nonparametric statistics to evaluate changes in these scores. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine whether there was a significant change in PHQ-9 scores between the baseline and final evaluation, and a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney test to determine whether final follow-up scores in the intervention group were significantly different from those in the control group. A 1-tailed test was used because subjects in both groups received standard treatments for depression that are known to decrease the severity of depression.30–33 We defined significance as a P value <.05.

We used Spearman's correlation coefficients to determine the relationship between REALM and PHQ-9 scores at baseline. We used the Pearson χ2 statistic and Fisher's exact test to evaluate differences in the proportion of subjects in each group who received psychological counseling. To evaluate differences in REALM scores over time, whose distribution approximated a normal distribution, we used 2-tailed t tests. Demographics were reported with descriptive statistics.

Based on published studies using the PHQ-9 in primary care settings, in which mean PHQ-9 scores are about 15 with a standard deviation of 6, and accounting for a proportion of subjects being lost to follow-up, our a priori sample size calculations indicated the need to enroll and randomize approximately 70 subjects. This would provide 80% power to detect a between-group change in PHQ-9 scores of ≥4 units (e.g., a change in score from 15 to 11).34

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of Subjects

Seventy subjects were enrolled, with 38 randomized to the intervention group and 32 to the control group. Table 1 shows subjects' demographic characteristics and their baseline scores on the PHQ-9 and REALM. Subjects in both groups had similar baseline median PHQ-9 scores. They also had similar baseline scores on the REALM, with mean scores corresponding to a seventh to eighth-grade reading level. There was no significant correlation between baseline PHQ-9 and REALM scores (Spearman's correlation=0.10, P=.43).

Table 1. Subject Demographics at Baseline.

| Characteristic | Intervention Group (N=38) | Control Group (N=32) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y (± SD) | 41.4 (± 14.3) | 43.7 (± 15.3) |

| Gender (number [%]) | ||

| Female | 16 (42.1) | 15 (46.9) |

| Male | 22 (57.9) | 17 (53.1) |

| Ethnic group (number [%]) | ||

| White | 37 (97.4) | 28 (87.5) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.6) | 2 (6.3) |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 2 (6.3) |

| Insurance status (number [%]) | ||

| Medicaid or Self-Pay | 19 (50.0) | 19 (59.4) |

| Medicare | 17 (44.7) | 12 (37.5) |

| Private (commercial) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (3.1) |

| Other | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Occupation (number [%]) | ||

| Employed (unskilled worker) | 9 (23.6) | 9 (28.0) |

| Small business owner | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) |

| Unemployed | 29 (76.4) | 22 (68.9) |

| PHQ-9 score (median) | 12.5 | 14 |

| REALM score (mean ± SD) | 46.5 (± 11.9) | 47.1 (± 15.9) |

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire (depression assessment instrument); REALM, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine.

Follow-up Rates

Of the 70 subjects, final follow-up data are available for 28 (88%) in the control group and 33 (87%) in the intervention group. There was no significant difference between those who completed a final assessment and those who dropped out at or before the first follow-up visit in terms of baseline PHQ-9 score, REALM score, gender, marital status, ethnicity, insurance status, or age.

Depression Treatment

Based on medical records review, a similar proportion of subjects in each group received treatment with antidepressant medications; 30 (78.9%) subjects in the intervention group and 26 (81.3%) in the control group received such treatment (P=.81). Record review also revealed that 20 (52.6%) subjects in the intervention group and 13 (40.6%) in the control group received counseling; this difference was not significant (P=.32).

Changes in Depression Severity

Changes in PHQ-9 scores are illustrated in Figure 2 and details are shown in Table 2. As already noted, the mean PHQ-9 scores were similar in both groups at baseline. Both groups experienced a significant decrease in PHQ-9 scores over time (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The decrease in scores was significantly larger in the intervention group, with final follow-up scores declining to 6 in that group, but only to 10 in the control group.

FIGURE 2.

Changes in PHQ-9 score over time. Diamonds represent PHQ-9 scores in the intervention group. Squares represent PHQ-9 scores in the control group. PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire (depression assessment instrument).

Table 2. Changes in PHQ-9 Scores Over Time†.

| Group | Baseline | First Follow-up | Second Follow-up | Final Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Median | No. | Median | Significance* | No. | Median | Significance* | No.‡ | Median | Significance* | |

| Intervention | 38 | 12.5 | 33 | 8 | P<.001 | 29 | 6 | P<.001 | 33 | 6 | P<.001 |

| Control | 32 | 14 | 27 | 8 | P=.003 | 25 | 9 | P=.004 | 28 | 10 | P<.001 |

| Significance** | .31 | .25 | .03 | .04. | |||||||

Significance of difference between baseline and follow-up scores, by Wilcoxon's signed-rank test.

Significance of difference in scores between intervention and control group, by 1-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

PHQ-9 scores can range from 0 to 27. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

The number of subjects is higher for the final follow-up than for earlier follow-ups because some subjects missed earlier follow-up visits but were present for the final follow-up.

No., number of subjects; NS, not significant; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire (depression assessment instrument).

Literacy Training and Outcomes

Intervention group subjects spent a mean of 18.1 hours attending ABLE classes. Attendance ranged from no participation at all (18.4% of subjects) to 74 hours (2.4%), with both modal and median values of 12 hours. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine scores in the intervention group increased by an average of 7 points between baseline and final follow-up (P=.001). There was no correlation, however, between hours of ABLE attendance and change in depression severity (r=.08, P=.66).

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of our study is that at final follow-up, depression severity was lower among participants assigned to receive literacy training plus standard depression treatment than it was among participants assigned to receive only standard depression treatment. Literacy skills, as measured by the REALM, improved in subjects assigned to receive literacy training, and their depression severity lessened.

This finding is important for several reasons. First, it provides the first evidence that outcomes of a disease—in this case, depression—can be improved by identifying individuals with the disease who also have limited literacy, and providing them with literacy education. Second, if borne out by larger and more rigorous trials, the results have implications for treatment of depression for millions of Americans. With 40% to 50% of the adult United States population (90 million people) having limited literacy skills, and 10% having depression, one can estimate that some 9 million (10% of 90 million) Americans have both limited literacy and depression. The true number may be even higher, as 1 study suggests that as many as 18 million American adults simultaneously have limited literacy and depression.35

Although the results of our study are preliminary, support for our findings comes from the results of a study by Poresky and Daniels.36 These investigators randomized parents of Head Start children to receive either (a) special services aimed at increasing parent's employability, with a focus on enhancing literacy skills, or (b) routine Head Start services. Their study did not limit enrollment only to parents with depression, but one outcome monitored by the investigators was depression, measured by the Centers for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). After 2 years, the percentage of parents classified as depressed on the CES-D declined from 48% at baseline to 23% among those receiving special services that include literacy training. Those receiving routine Head Start services without literacy training had no change in depression scores.

Limitations

As a preliminary investigation, our study results are subject to a number of limitations. One limitation is that our sample size was small, raising the possibility that differences in depression scores between the 2 study groups were due to chance. Statistical tests indicate otherwise, however, as the greater decline in depression severity in the intervention group compared with the control group was statistically significant. Nonetheless, replication of the study with a larger sample would provide more compelling evidence of the benefit of literacy training for the treatment of depression.

Furthermore, the small sample prevented us from determining whether there was a “dose-response” relationship between increased literacy and lessened depression. That is, we had too few subjects to determine whether those with the greatest degree of improvement in literacy skills experienced the greatest improvement in depression. We also could not determine whether any one educational modality of the ABLE program was more effective than others in decreasing depression. Future studies should include an assessment of a dose-response relationship and evaluate which educational modality is most helpful.

A second limitation is that our study was not designed to determine the degree of limited literacy for which literacy enhancement might offer benefit for patients with depression. That is, would individuals with depression be more likely to benefit from literacy training if they had, for example, second-grade reading skills rather than sixth-grade reading skills? Additional study is needed to answer this question.

A third limitation is that we relied solely on the PHQ-9 to categorize subjects as having depression, rather than performing a formal psychiatric interview. It is possible, therefore, that some subjects were incorrectly categorized as having or not having depression before entry into the study. We feel that it is unlikely that this occurred, because the PHQ-9 is a well-validated instrument that is known to be accurate in identifying patients with depression.

Finally, the mechanism by which literacy education might lessen depression symptoms is unclear and, in fact, lessened depression may not be the result of improved literacy. Rather, participation in literacy education classes may, by itself, give individuals a sense of improved self-esteem or self-efficacy, enhance their feelings of self-worth, and/or diminish feelings of shame associated with limited literacy. Improving these parameters may, in turn, decrease symptoms of depression. Further study is needed to determine the mechanism by which literacy education decreases symptoms of depression.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that there may be benefit to assessing the literacy skills of patients who are depressed, and recommending that patients with both depression and limited literacy consider enrolling in adult education classes to enhance literacy. Further study is needed to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Pfizer Health Literacy Initiative. The authors thank Maria Chavez and Maggie Murphy for their help with data coding and entry.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Education Statistics. National Assessment of Adult Literacy. A First Look at the Literacy of America's Adults in the 21st Century. NCES Publication No. 2006470. December 2005.

- 2.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1278–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gausman Benson J, Forman WB. Comprehension of written health care information in an affluent geriatric retirement community: use of the test of functional health literacy. Gerontology. 2002;48:93–7. doi: 10.1159/000048933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss BD, Reed RL, Kligman EW. Literacy skills and communication methods of low-income older persons. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;25:109–1. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00710-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Functional health literacy is associated with health status and health-related knowledge in people living with HIVAIDS. J Acq Immune Def Synd Hum Retrovirol. 2000;25:337–44. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman H, Skipper B, Small L, et al. Effect of literacy on breastfeeding outcomes. South Med J. 2001;94:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:475–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3101–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss BD, Hart G, McGee DL, et al. Health status of illiterate relation between literacy and health status among persons with literacy skills. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkman ND, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Literacy and Health Outcomes. 2004. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 87 (Prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016). AHRQ Publication No. 04-E007-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. January 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bloom BS. Prevalence and economic effects of depression. Manag Care. 2004;13(6 Suppl):9–16. Depression. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. June 2003;289:3095–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: the unspoken connection. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:33–9. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wardle J, Steptoe A, Gulis G, et al. Depression, perceived control, and life satisfaction in university students from Central-Eastern and Western Europe. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11:27–36. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1101_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiner AS, Morimoto T. The relationship between mastery and depression among Japanese family caregivers. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;56:307–21. doi: 10.2190/7ERL-TF1D-KW2X-3C7Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blazer DG. Self-efficacy and depression in late life: a primary prevention proposal. Aging Mental Health. 2002;6:315–24. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000006938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6:197–205. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss BD, Coyne C, Michielutte R, et al. Communicating with patients who have limited literacy skills: report of the National Work Group on Literacy and Health. J Fam Prac. 1998;46:168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck JG, Novy DM, Diefenbach GJ, Stanley MA, Averill PM, Swann AC. Differentiating anxiety and depression in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychol Assess. 2003;15:184–92. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.184. Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2004. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis TC, Long S, Jackson R, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine:a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. http://www.healthdisparities.net/hdc/html/collaboratives.topics.depression.aspx

- 25.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Burns MR, Winchell CW, Chin T. Application of a depression management office system in community practice: a demonstration. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:107–14. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the PHQ-9. Med Care. 2004;42:1194–201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.TABE: Tests of Adult Basic Education. Monterey, CA: CTB/McGraw-Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.PowerPath to Basic Learning. PowerPath/TLP Group. 2000 http://www.powerpath.com.

- 29.Streiner DL. The case of the missing data: methods of dealing with dropouts and other research vagaries. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joffe R, Sokolov S, Streiner D. Antidepressant treatment of depression: a metaanalysis. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:613–6. doi: 10.1177/070674379604101002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:714–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine v. placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short-term treatment of major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:421–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, et al. Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1009–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rollins B. Sample size and power calculations. Institute for Medical Statistics, Medical University of Vienna. Available at: http://www.meduniwien.ac.at/medstat/research/samplesize/ssize.html.

- 35.Gazmararian J, Baker D, Parker R, Blazer DG. A multivariate analysis of factors associated with depression: evaluating the role of health literacy as a potential contributor. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3307–14. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poresky RH, Daniels AM. Two-year comparison of income, education, and depression among parents participating in regular Head Start or supplementary family service center services. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:787–96. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]