Abstract

BACKGROUND

Little is known about patient characteristics associated with comprehension of consent information, and whether modifications to the consent process can promote understanding.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a modified research consent process, and determine whether literacy and demographic characteristics are associated with understanding consent information.

DESIGN

Descriptive study of a modified consent process: consent form (written at a sixth-grade level) read to participants, combined with 7 comprehension questions and targeted education, repeated until comprehension achieved (teach-to-goal).

PARTICIPANTS

Two hundred and four ethnically diverse subjects, aged ≥50, consenting for a trial to improve the forms used for advance directives.

MEASUREMENTS

Number of passes through the consent process required to achieve complete comprehension. Literacy assessed in English and Spanish with the Short Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (scores 0 to 36).

RESULTS

Participants had a mean age of 61 years and 40% had limited literacy (s-TOHFLA<23). Only 28% of subjects answered all comprehension questions correctly on the first pass. After adjustment, lower literacy (P=.04) and being black (P=.03) were associated with requiring more passes through the consent process. Not speaking English as a primary language was associated with requiring more passes through the consent process in bivariate analyses (P<.01), but not in multivariable analyses (P>.05). After the second pass, most subjects (80%) answered all questions correctly. With a teach-to-goal strategy, 98% of participants who engaged in the consent process achieved complete comprehension.

CONCLUSIONS

Lower literacy and minority status are important determinants of understanding consent information. Using a modified consent process, little additional education was required to achieve complete comprehension, regardless of literacy or language barriers.

Keywords: informed consent, health literacy, communication, vulnerable populations, ethics

It is unknown whether literacy is an important determinant of comprehension of consent information, or what methods could enhance the process for individuals with literacy or language barriers. While informed consent provides the legal and ethical basis for participation in research and clinical procedures, 40% to 80% of subjects with the capacity to consent do not understand 1 or more aspects of consent information.1,2 Low literacy is likely an important factor as approximately half of American adults read at or below an eighth-grade reading level.3,4 Most consent forms, however, are written far beyond this level, and with a complexity that often hinders understanding.5–8

Modifications to the standard consent process that may enhance understanding include improving the readability and design of consent forms,9–16 and allowing ample time for discussion of consent information.10 Understanding may also be enhanced by using an iterative, educational strategy in which formal assessment of comprehension is linked to repeated passes through targeted education until understanding is obtained17–24 (a process also known as “teach-to-goal”).25 The degree to which these modifications may improve the consent process among diverse populations with limited literacy, and the patient characteristics associated with understanding consent information, have not been established.

As part of a randomized trial to improve the forms used for advance directives, we modified the consent process for all participants by: (1) using a consent form written at the sixth-grade reading level, (2) having bilingual research assistants read this form to potential subjects, and (3) by using a teach-to-goal strategy. The goal of this paper is to describe the modified consent process, and to determine whether literacy and other subject characteristics (specifically race/ethnicity and language) were associated with comprehension of consent information and the number of passes required through the teach-to-goal process to achieve comprehension.

METHODS

Study Participants and Recruitment

This study was nested in a trial of 2 advance directives.26 The consent substudy was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (IRB) within the context of this trial. Participants were recruited between August and December, 2004 from the General Medicine Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, a public hospital where up to half of the patients have limited literacy.27

Participants were eligible if they had a primary care physician, were 50 years or older, and reported speaking either English or Spanish “well” or “very well.” Participants were excluded if they had dementia, or were deaf, delirious, or not well enough to complete the interview. These assessments were made by participants' physicians before contact with research staff. Study staff then confirmed inclusion/exclusion criteria (except dementia), and further excluded participants whose corrected visual acuity was <20/100.28 Participants were interviewed by either white/non-Hispanic, native English-speaking staff (3 interviewers) or white/Hispanic, native Spanish-speaking staff (2 interviewers). Participants were offered $20 for trial participation.

The Consent Form

The consent process was standardized. Participants were given a consent form using 12-point font and written at the sixth-grade reading level (except IRB required headings) (online Appendix), as determined by 2 validated methods and by 2 independent evaluators.29,30 The information was written using concrete explanations and contextual clues, while adhering to the IRB standard template.10 The consent form was translated into Spanish, back translated, and pilot tested by native Spanish speakers to ensure concordant meaning. At the time of consent, participants were given a copy of the consent form (in English or Spanish) and were asked to read along while the form was slowly read to them verbatim over approximately 10 minutes. Participants were asked whether they had any questions after reading each section of the form, and after reading it in its entirety. We attempted to standardize answers to anticipated questions.

Consent Comprehension Assessment

Participants were told that to participate in the intervention study, study staff needed to ensure they had described the study clearly. We then read participants 7 true/false comprehension statements concerning study procedures, risk, and confidentiality (Table 1). Three of the statements were true and 4 were false. Five contained text derived directly from the consent form (questions 2, 4, 5, 6, 7) (highlighted sections in online Appendix) and 2 did not (questions 1 and 3). Possible responses included “true,”“false,” or “I don't know;” participants were encouraged to answer “I don't know” rather than to guess. Subject responses were dichotomized into correct or incorrect by combining an incorrect answer with an “I don't know” response.

Table 1. Comprehension Statements* and Percent Answered Correctly on the First Pass, N=204.

| 1. If you choose to be in this study, you will need to get your blood drawn (false) | 78% |

| 2. If you choose to be in this study, you need to look at two medical forms (true) | 71% |

| 3. If you choose to be in this study, you will need to watch a video (false) | 73% |

| 4. If you choose to be in this study, you will need to answer some medical questions about yourself (true) | 80% |

| 5. You were chosen to be in this study because you see a doctor in this hospital (true) | 87% |

| 6. You were chosen to be in this study because your doctor thinks that you are sick and that you need an advance directive form (false) | 85% |

| 7. After you fill out the study advance directive forms today, we will give them to your doctor and put them in your medical chart (false) | 79% |

All question responses were either “true,”“false,” or “I don't know.” Correct answers are shown in parentheses.

Teach-To-Goal Strategy

Participants had to respond correctly to all statements to participate in the trial of advance directives. If a participant responded incorrectly to any statement on the first pass of questioning, those sections of the consent form corresponding to each missed statement were re-read. Missed statements were then repeated. If on the second pass, participants again incorrectly responded to any statement, the corresponding sections of the consent form were again re-read and the statements again repeated. Participants were read the statements up to 3 times, after which they were assessed for dementia with the Mini-Cog exam.31 Participants who screened positive for dementia were excluded. Those who did not screen positive were allowed up to an additional 3 passes through the consent form and comprehension statements, beyond which they were deemed ineligible. Participants who required 3 or fewer passes were also assessed for dementia after consent was obtained. A random sample of 20 (10%) of consent discussions were observed and found to follow the research protocol consistently.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of passes through the teach-to-goal consent process (consent form and comprehension statements) required to obtain consent. We categorized this outcome into (1) requiring 1 pass, (2) requiring a second pass, or (3) requiring 3 or more passes before answering all statements correctly.

We also assessed the number of comprehension statements missed on the first pass of questioning. This outcome variable was categorized into (1) responding correctly to all statements on the first pass, (2) responding incorrectly to 1 statement, and (3) responding incorrectly to 2 or more statements.

Primary Predictors

Literacy and Language.

Literacy was assessed for consented participants with the Short Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test.32 We used the s-TOFHLA score as a continuous variable, and categorized scores into: inadequate (s-TOFHLA score of 0 to 16), marginal (17 to 22), or adequate (23 to 36).

In addition to requiring self-reported English or Spanish proficiency for eligibility, we asked which language the consented participants felt most comfortable speaking (English, Spanish, or Other).

Sociodemographics.

To establish eligibility, we obtained self-reported age. For consented participants, we also obtained race/ethnicity, gender, income, educational attainment, place of birth (born in or outside the United States) and, for those born outside the United States, and number of years lived in the United States. If more than 10% of data were missing for any variable, this information was imputed from other known demographic variables.

Statistical Analyses

We measured the proportion of each comprehension statement answered correctly on the first pass of questioning to assess whether there were statements or domains of consent that were more challenging than others.

Then, we assessed the distribution of the outcomes (number of passes required to complete the consent process [1, 2, or ≥3] and number of comprehension statements missed on the first pass of questioning [none, 1, or ≥2]).

In an attempt to estimate the extent of subject fidelity to our instructions to report “I don't know” rather than to guess, and to estimate the degree to which participant responses may have reflected test-taking strategies (i.e., guessing), we assessed the percentage of incorrect statements because of choosing an incorrect true/false response versus an “I don't know” response at each pass of the consent process. We assessed the associations between participants' literacy level (inadequate, marginal, or adequate), language, and other characteristics with both outcomes and whether participants reported “I don't know” using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test.

To determine the independent association of literacy, language, and other characteristics with our outcomes, we constructed a series of multivariable ordinal logistic regression models. Literacy was used as a continuous variable and other demographic variables were included if they were associated with the outcome variables at P≤.2 in bivariate analysis. In the multivariable models, if predictor variables were correlated at a Pearson's correlation coefficient ≥0.80, the variable with the greater statistical association was retained.

We tested for interactions between literacy, language, and the number of passes required for complete comprehension and the number of comprehension questions missed using stratified analyses, the Mantel-Haenszel method, and by entering an interaction term into our ordinal logistic regression models.

Multivariable models were assessed with and without imputed predictor variables, data from participants who screened positive for dementia, and an interviewer covariate. All analyses were conducted using intercooled Stata, version 8 software.33

RESULTS

Study staff approached 329 potential participants. Twenty participants refused to participate, 39 were willing to participate but could not schedule an interview during the study period, 61 did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data were missing for 1 participant, leaving 208 participants. Participants who were or were not included in the study did not differ in age (P=.20); however, more non-English/non-Spanish speaking participants were not included (57.1% vs 42.9%, P<.01). Only 4 participants who engaged in the consent process (2%) could not achieve complete comprehension of consent information within 6 passes. These participants did not differ in age or language from the remaining sample (P>.05). As these participants could not complete the consent process, no further study information was collected.

The remaining sample (N=204) was racially/ethnically diverse and of lower socioeconomic status (Table 2). One-third of the sample had not completed high school, 40% had less than adequate literacy, and 46% were non-English speaking.

Table 2. Characteristics of 204 Study Participants.

| Characteristic | % or Mean (± SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61 (8.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/Non-Hispanic | 26 |

| White/Hispanic | 31 |

| Black | 24 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 |

| Multiethnic/other | 10 |

| Female | 53 |

| Yearly income ≤$10,000* | 48 |

| Education | |

| <High school | 32 |

| High school graduate | 19 |

| Some college to graduate degree | 49 |

| Literacy level† | |

| Adequate | 60 |

| Marginal | 18 |

| Inadequate | 22 |

| Language most comfortable speaking | |

| English | 62 |

| Spanish | 29 |

| Other‡ | 9 |

| U.S. born | 60 |

| If not U.S. born, years lived in United States | |

| >10 | 86 |

Income data only available for 169 (83%) participants.

Literacy level defined by s-TOFHLA literacy score (possible range: 0 to 36; mean ± SD: 24.6 ± 10.8). Inadequate literacy, 0 to 16; marginal literacy, 17 to 22; adequate literacy, 22 to 36.

Subjects in the “other” category reported speaking English “well or “very well,” but were most comfortable speaking their native language (e.g., Cantonese, Tagalog, etc.).

s-TOFHLA, Short Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults.

The proportion of each of the 7 comprehension statements that participants responded to correctly on the first pass ranged from 71% to 87% (Table 1).

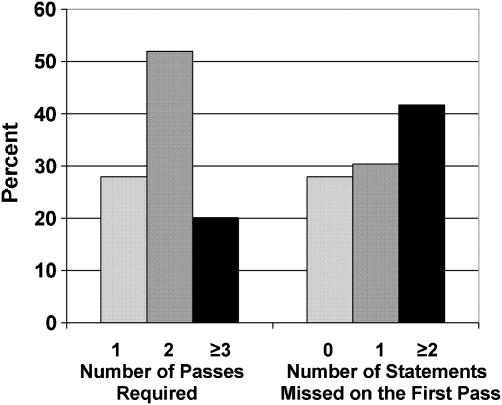

Only 57 (28%) participants responded correctly to all of the comprehension statements, thereby requiring only 1 pass through the consent process (Fig. 1), 106 (52%) required a second pass, and 41 (20%) required 3 or more passes. Sixty-two (30%) participants missed one comprehension statement on the first pass, and 82 (42%) missed 2 or more statements.

FIGURE 1.

The number of passes required to complete consent process and number of statements missed on the first pass, N=204.

Participants were likely to require more passes if they were older (P=.04), were black or Asian/Pacific Islander (P≤=.01), were female (P=.03), had lower educational attainment (P=.02), had less than adequate literacy (P=.02), felt most comfortable speaking a language other than English or Spanish (P<.01), or were born outside the United States (P<.01) (Table 3). With the exception of gender, these associations were also present for the number of comprehension questions missed.

Table 3. Number of Passes Required Through the Consent Process to Obtain Informed Consent*, by Participant Characteristic.

| Participant characteristic | Required only 1 Pass (%) | Required 2 Passes (%) | Required ≥3 Passes (%) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| 50 to 54 (n=51) | 41.2 | 51.0 | 7.8 | .04 |

| 55 to 58 (n=53) | 17.0 | 62.3 | 20.7 | |

| 59 to 65 (n=52) | 28.8 | 44.2 | 26.9 | |

| 66 to 91 (n=48) | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White/Non-Hispanic (n=52) | 46.1 | 42.3 | 11.5 | <.01 |

| White/Hispanic (n=63) | 15.9 | 76.2 | 7.9 | |

| Black (n=49) | 28.6 | 40.8 | 30.6 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (n=19) | 5.3 | 31.6 | 63.1 | |

| Multiethnic/other (n=21) | 38.1 | 47.6 | 14.3 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (n=96) | 33.3 | 54.2 | 12.5 | .03 |

| Female (n=108) | 23.1 | 50.0 | 26.8 | |

| Yearly income‡ | ||||

| > $10,000 (n=87) | 36.8 | 44.8 | 18.4 | .14 |

| ≤$10,000 (n=82) | 24.4 | 47.6 | 28.1 | |

| Education level | ||||

| Some college-graduate degree (n=100) | 36.0 | 42.0 | 22.0 | .02 |

| High school (n=39) | 28.2 | 48.7 | 23.1 | |

| <High school (n=64) | 15.6 | 68.8 | 15.6 | |

| Literacy level§ | ||||

| Adequate (n=122) | 36.1 | 45.1 | 18.8 | .02 |

| Marginal (n=37) | 21.6 | 62.2 | 16.2 | |

| Inadequate (n=45) | 11.1 | 62.2 | 26.7 | |

| Language most comfortable speaking | ||||

| English (n=127) | 37.0 | 43.3 | 19.7 | <.01 |

| Spanish (n=59) | 32.4 | 42.1 | 25.5 | |

| Other (n=18)∥ | 5.6 | 27.8 | 66.7 | |

| U.S. born (n=123) | 36.6 | 46.3 | 17.1 | <.01 |

| Born outside United States (n=81) | 14.8 | 60.5 | 24.7 | |

| Years lived in United States if born outside United States | ||||

| 0 to 10 (n=11) | 18.2 | 63.6 | 18.2 | .85 |

| >10 (n=70) | 14.3 | 60.0 | 25.7 | |

The number of passes through the comprehension questions and through the consent form required to correctly answer all comprehension questions

P Value reflects comparisons across 3 groups: all comprehension statements correct on first pass, requiring a second pass, requiring ≥3 passes (up to 6) to correctly answer all statements

Income data only available for 169 (83%) participants

Literacy level defined by s-TOFHLA literacy score: Inadequate literacy, 0 to 16; marginal literacy, 17 to 22; adequate literacy, 22 to 36

Subjects in the “Other” category reported speaking English “well or “very well,” but were most comfortable speaking their native language (e.g., Cantonese, Tagalog, etc.)

s-TOFHLA, Short Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults.

Of participants requiring a second pass through the consent process (n=147), 46% stated “I don't know” to 1 or more of the comprehension statements. Of participants requiring 3 or more passes (n=41), 39% stated “I don't know” during subsequent passes, rather than choosing an incorrect answer. Stating “I don't know” was not associated with literacy or other patient characteristics, P>.05.

After adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, education, gender, primary language, and s-TOFHLA score in multivariable ordinal models, only lower literacy and minority status were significantly associated with requiring more passes through the consent process and missing more comprehension statements. Participants' odds of requiring more passes increased with each 1-point decrease in s-TOFHLA score (odds ratio [OR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00 to 1.07) with odds ratios ranging from 1.00 for those with s-TOFHLA scores of 36, to 3.76 for those who scored 0 of 36. Being black was also associated with requiring more passes (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.08 to 5.56). Participants with lower literacy scores were also likely to miss more comprehension statements on the first pass (for every 1-point decrease in s-TOFHLA score: OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.07), with odds ranging from 1.00 for those with s-TOFHLA scores of 36 to 3.71 for those who scored 0 out of 36. Being Asian/Pacific islander was also associated with missing more comprehension statements (OR, 5.27; 95% CI 1.02 to 27.30).

Mantel-Haenszel tests did not show heterogeneity in associations between literacy, language, and our outcomes, and interaction terms for literacy and language in our multivariable models were nonsignificant (P=.40 for passes required and .71 for statements missed). However, in stratified analyses, participants who engaged in the consent process in a language other than their primary language, regardless of literacy level, required more passes. For example, all of the nonnative English speakers who had either inadequate or marginal literacy (n=12) required more than 1 pass through the consent process. In addition, 83% of nonnative English participants in the highest literacy level (n=6) required more than 1 pass as compared with only 75% of native English speakers in the lowest literacy level (n=12) (test for trend across the 3 literacy categories, P=.04).

Thirty-five participants (17%) had missing income data and were assigned imputed values based on the median value of participants with similar age, race, gender, and education. Seven participants (3.4%) tested positive for dementia. Inclusion of imputed income variables, controlling for interviewer, or exclusion of participants with dementia did not appreciably alter our results.

DISCUSSION

Despite significant consent modifications (improving readability of the consent form, having bilingual research assistants read the consent form to participants, and allowing time for discussion), few participants (28%) had complete comprehension and required only 1 pass through the consent process. However, further use of a teach-to-goal strategy25 was successful in achieving complete comprehension in 98% of all participants who engaged in the consent process, including those with literacy or language barriers. Participants with lower literacy and minority status were at greatest risk for poor comprehension. Nonetheless, most participants (80%) required little additional education to achieve complete comprehension (e.g., only 1 or 2 more passes through missed comprehension statements and corresponding consent sections).

After adjustment, minority status was independently associated with poor comprehension and requiring more passes through the consent process, suggesting that other factors, such as mistrust or racial/ethnic discordance between interviewer and subject, may contribute to poor understanding.34–36 While we could not assess the effects of racial/ethnic concordance on comprehension (research assistants were only white/non-Hispanic or white/Hispanic), our results suggest that race/ethnic concordance should be addressed in future consent studies.

Literacy and language also appear to be important determinants of comprehension and the number of passes required to achieve consent. These results are consistent with other studies demonstrating that literacy, language, or educational barriers are associated with poor comprehension of health education or consent information.9,13,21,22,37–45 Future studies should further explore the interaction between literacy and language on comprehension.

Our study has important implications for consent in the research and possibly the clinical setting. First, many subjects may be signing consent forms and agreeing to participate without truly understanding what is being asked of them.6 This raises ethical concerns for research in vulnerable populations, represents a risk of liability to researchers and clinicians, and may introduce personal risk to study participants or patients, particularly for studies or procedures with high risk to benefit ratios.46

Second, if the consent process includes consent forms that are written at or below the sixth-grade level, are read to subjects, and include a “teach-to-goal” strategy, then it may be possible to convey key elements of consent and reduce disparities in comprehension for vulnerable populations.25,47–49 In most cases, simply identifying and reviewing items that were not understood the first time can accomplish this. Interactive, educational consent methods currently advocated for use in both research and clinical settings may be especially important for those with limited literacy, minority status, or those who speak a primary language other than English.17–24,50 It may be more effective to use open-ended questions to assess understanding or, if using close-ended questions, to encourage subjects to state that they “don't know” to avoid guessing and promote discussion.

Third, poor comprehension appears to be more pronounced in nonnative English speakers, even if they report English proficiency.43 Therefore, to maximize the likelihood that consent information will be understood, informed consent may need to be obtained in participants' native language. However, it is also clear that researchers and clinicians should not assume that any potential participant or patient, regardless of literacy level or language spoken, will understand consent information.

Finally, this iterative consent process only led to the exclusion of 4 (2%) eligible subjects who were willing to participate. No eligible subjects refused to participate by virtue of being better informed. Using a modified consent form and an iterative consent process may enhance informed consent for vulnerable, diverse populations, without significantly reducing participation rates. Improved understanding may actually foster trust and facilitate recruitment of diverse populations.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the comprehension statements could have addressed all of the required elements of informed consent, making our results more generalizable.51 Second, some participants may have had better test-taking strategies (i.e., guessing correctly) on the first pass or the iterative consent process could have led participants to select logically the opposite answer on subsequent passes without true comprehension.19 However, almost half of participants with incorrect responses stated “I don't know,” suggesting honest disclosure instead of using test-taking strategies. Third, while we attempted to standardize the consent process, we did not directly observe all interviews and therefore could not account for variability in interviewer/subject interactions, the type and frequency of questions asked by participants, and the time taken to discuss consent information. Fourth, as we were asking subjects to read the consent form simultaneously as it was read to them, we cannot disentangle reading from oral comprehension. Fifth, there was no control group and therefore comparisons with a standard consent process cannot be made. Finally, this study was performed at 1 site for a low-risk trial, limiting the generalizability with respect to other settings, study designs, and studies with different risk to benefit ratios.

CONCLUSION

Despite using a number of consent modifications, most participants had poor comprehension on the first pass through the consent process. Lower literacy and minority status were associated with requiring more passes to achieve complete comprehension of consent information. The role of primary language may also be important and merits further research. Nonetheless, by using a modified consent approach (improving the readability and design of the consent form, reading the consent form to participants in their native language, and using an iterative, teach-to-goal strategy), complete comprehension of consent information was achieved for 98% of participants who engaged in the consent process, including those with literacy and language barriers. For the majority of these participants, little additional education was required. Using these modifications to the consent process may improve the quality of informed consent for diverse populations. If confirmed in other settings, this approach should become the standard means to elicit informed consent for research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Medical Association Foundation, Health Literacy Grants for Residents and Fellows, and pilot funds from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging K07 AG000912. Dr. Sudore was supported by the National Institutes of Health Research Training in Geriatric Medicine Grant: AG000212 and by the Pfizer Fellowship in Clear Health Communication. Dr. Schillinger was supported by an NIH Mentored Clinical Scientist Award K-23 RR16539-03. Dr. Barnes was a consultant for a research study design and analysis for Posit Science Corporation in 2003.

Supplementary material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com.

Consent to be a Research Subject.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wendler D. Can we ensure that all research subjects give valid consent? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2201–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358:1772–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss BD, Blanchard JS, McGee DL, et al. Illiteracy among Medicaid recipients and its relationship to health care costs. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1994;5:99–111. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stedman LD, Kaestle CF. Literacy and reading performance in the United States from 1880 to the present. In: Kaestle CF, editor. Literacy in the United States: Readers and Reading Since 1880. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1991. pp. 75–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine R. Ethics and Regulations of Clinical Research. 2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:721–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murgatroyd RJ, Cooper RM. Readability of informed consent forms. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1991;48:2651–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundner TM. On the readability of surgical consent forms. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:900–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004173021606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis TC, Holcombe RF, Berkel HJ, Pramanik S, Divers SG. Informed consent for clinical trials: a comparative study of standard versus simplified forms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:668–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.9.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Philipson SJ. Improving the readability and processability of a pediatric informed consent document: effects on parents' understanding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:347–52. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell FA, Goldman BD, Boccia ML, Skinner M. The effect of format modifications and reading comprehension on recall of informed consent information by low-income parents a comparison of print, video, and computer-based presentations. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:205–16. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young DR, Hooker DT, Freeberg FE. Informed consent documents: increasing comprehension by reducing reading level. IRB. 1990;12:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers CG, Tyson JE, Kennedy KA, Broyles RS, Hickman JF. Conventional consent with opting in versus simplified consent with opting out: an exploratory trial for studies that do not increase patient risk. J Pediatr. 1998;132:606–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjorn E, Rossel P, Holm S. Can the written information to research subjects be improved?—An empirical study. J Med Ethics. 1999;25:263–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.25.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy DA, O'Keefe ZH, Kaufman AH. Improving comprehension and recall of information for an HIV vaccine trial among women at risk for HIV: reading level simplification and inclusion of pictures to illustrate key concepts. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11:389–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dresden GM, Levitt MA. Modifying a standard industry clinical trial consent form improves patient information retention as part of the informed consent process. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:246–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:139–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coletti AS, Heagerty P, Sheon AR, et al. Randomized, controlled evaluation of a prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:161–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants' understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004;292:1593–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller CK, O'Donnell DC, Searight HR, Barbarash RA. The Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test: an assessment tool for clinical research subjects. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:872–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taub HA, Baker MT. The effect of repeated testing upon comprehension of informed consent materials by elderly volunteers. Exp Aging Res. 1983;9:135–8. doi: 10.1080/03610738308258441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taub HA, Kline GE, Baker MT. The elderly and informed consent: effects of vocabulary level and corrected feedback. Exp Aging Res. 1981;7:137–46. doi: 10.1080/03610738108259796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Mintz J. Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1508–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stiles PG, Poythress NG, Hall A, Falkenbach D, Williams R. Improving understanding of research consent disclosures among persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:780–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudore RL, Brody R, Lin L, Schillinger D. Code status unknown: tailoring an advanced health care directive form to the literacy levels of patients at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(suppl 1):88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tannenbaum S. The eye chart and Dr. Snellen. J Am Optom Assoc. 1971;42:89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Research Branch report 8-75. Memphis: Naval Air Station: 1975. Derivation of anew readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading: a new readability formula. J Reading. 1969;12:639–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1451–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.STATA. Statistics/Data Analysis. Intercooled, Version 8.0. College Station, TX: STATA; 1984–2003. [December 14, 2005]. Available at: http://www.stata.com. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbie-Smith GM. Minority recruitment and participation in health research. NC Med J. 2004;65:385–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torke AM, Corbie-Smith GM, Branch WT., Jr African American patients' perspectives on medical decision making. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:525–30. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Arnold C, Murphy PW, Herbst M, Bocchini JA. A polio immunization pamphlet with increased appeal and simplified language does not improve comprehension to an acceptable level. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Jr, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(part 1):804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coyne CA, Xu R, Raich P, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an easy-to-read informed consent statement for clinical trial participation: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:836–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:329–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.6.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taub HA, Baker MT, Kline GE, Sturr JF. Comprehension of informed consent information by young-old through old-old volunteers. Exp Aging Res. 1987;13:173–8. doi: 10.1080/03610738708259321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leyva M, Sharif I, Ozuah PO. Health literacy among Spanish-speaking Latino parents with limited English proficiency. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:56–9. doi: 10.1367/A04-093R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betancourt JR, Jacobs EA. Language barriers to informed consent and confidentiality: the impact on women's health. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2000;55:294–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts CM. Meeting the needs of patients with limited English proficiency. J Med Pract Manage. 2001;17:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pape T. Legal and ethical considerations of informed consent. AORN J. 1997;65:1122–7. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)62955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taub HA, Baker MT. A reevaluation of informed consent in the elderly: a method for improving comprehension through direct testing. Clin Res. 1984;32:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunn LB, Lindamer LA, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Schneiderman LJ, Jeste DV. Improving understanding of research consent in middle-aged and elderly patients with psychotic disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:142–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn LB, Jeste DV. Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:595–607. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The National Quality Forum. Learning from early adopters: improving patient safety through informed consent in limited english proficiency/low-literacy populations. [December 14, 2005];2005 Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/txinformedconsent1pager12-07-03.pdf.

- 51.Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of human subjects. [December 14, 2005];2005 Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Consent to be a Research Subject.