Abstract

BACKGROUND

We studied female graduates of the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (CSP, Class of 1984 to 1989) to explore and describe the complexity of creating balance in the life of mid-career academic woman physicians.

METHODS

We conducted and qualitatively analyzed (κ 0.35 to 1.0 for theme identification among rater pairs) data from a semi-structured survey of 21 women and obtained their curricula vitae to quantify publications and grant support, measures of academic productivity.

RESULTS

Sixteen of 21 (76%) women completed the survey. Mean age was 48 (range: 45 to 56). Three were full professors, 10 were associate professors, and 3 had left academic medicine. Eleven women had had children (mean 2.4; range: 1 to 3) and 3 worked part-time. From these data, the conceptual model expands on 3 key themes: (1) defining, navigating, and negotiating success, (2) making life work, and (3) making work work. The women who described themselves as satisfied with their careers (10/16) had clarity of values and goals and a sense of control over their time. Those less satisfied with their careers (6/16) emphasized the personal and professional costs of the struggle to balance their lives and described explicit institutional barriers to fulfillment of their potential.

CONCLUSION

For this group of fellowship-prepared academic women physicians satisfaction is achieving professional and personal balance.

Keywords: career planning, mentoring, academic careers, women physicians, working women, research skills

THE ARMFUL

Robert Frost

For every parcel I stoop down to seize

I lose some other off my arms and knees,

And the whole pile is slipping, bottles, buns

Extremes too hard to comprehend at once

Yet nothing I should care to leave behind.

With all I have to hold with hand and mind

And heart, if need be, I will do my best.

To keep their building balanced at my breast.

I crouch down to prevent them as they fall;

Then sit down in the middle of them all.

I had to drop the armful in the road

And try to stack them in a better load.1

Women are now entering medical school at a rate equal to that of men, but only account for 30% of medical school faculty, 14% of professors, and 7% of deans of American medical schools, creating a dearth of female academic role models and mentors.2 This deficiency deters from attracting and retaining the “best and the brightest” into academia.3 A 1987 national survey of full-time female faculty under age 50 found that most were highly satisfied with their careers despite the many struggles to balance their lives. However, only 32% felt they had a role model perceived as successful in balancing career and personal life.4

Since 1972, the Robert Wood Johnson (RWJ) Foundation has spent $775 million on the Clinical Scholars Program (CSP) to train nearly 1,000 young physicians to be scholarly research leaders in health services research and policy.5 By all accounts, the CSP has been very successful in achieving its mission; 75% of graduates take academic jobs right out of the program. Among the CSP graduates, there are 20 department chairs, 150 full professors, and many Chief Executive Officers in industry and agency directors at all levels of government. Initially, the clinical scholars were mostly men. However, this inequality appears to be waning. In 2004, the entering class was 60% women.

In 1989, we conducted a brief open-ended survey of all 36 women graduates of the CSP in the 5 years before accumulate strategies for creating personal and professional success in academic medicine. The 21 respondents reported detailed and valuable advice regarding initial job searches, personal and professional goals, and combining academics while raising a family. These women were hopeful, but realistic, as they struggled to establish academic careers, and successful personal lives.

In this paper we report on a follow-up survey we conducted in 2003, with those original respondents. We sought to engage them in describing the complexity of creating balance in one's life as a step in helping provide realistic and nuanced career guidance for the current generation of academic physicians.

METHODS

Respondents

Contact information for all 36 of the original respondents was obtained from the RWJ Clinical Scholars Program directory, which is updated annually by the Foundation. Our sample was purposive, rather than random and focused on a group of women uniquely prepared for academic success and willing to share their thoughts on balancing their lives.

Intervention

Based on our analysis of the 21 survey responses received in 1989 and a review of the relevant literature, we designed a semi-structured survey, and revised the instrument after an initial pilot with CSP graduates not in the final sample. We mailed or e-mailed the survey along with a copy of each woman's completed 1989 survey and requested current curriculum vitae (CV). After repeated mailings and phone calls, we received 16 of 21 completed surveys and 14 CVs. We did not have accurate contact information for 2 nonresponders who we know to have moved out of the country. Reason for nonresponse is not known for the remaining 3 subjects.

Table 1 lists the 10 open-ended questions from the survey instrument. Data, extracted from the available CVs, included: academic rank, number of first author publications, and total grant money obtained as principal investigator. This study was approved by the institutional review board on the study of human subjects.

Table 1.

The Survey Questions

| Questions: |

|---|

| 1. Briefly describe your current job commenting specifically on your: |

| a. Responsibilities |

| b. The hours you spend at work |

| c. The hours you spend working at home |

| 2. What do you consider to be your greatest accomplishments and greatest successes at work? In what ways are these different from how your peers (or the Promotions and Tenure committee) define success? |

| 3. How do you balance your work life with your home life? Please give specific examples. |

| 4. How satisfied are you with your career since leaving CSP? Describe your predominant feelings about what you have accomplished in your career so far. |

| 5. We are interested in how your job has evolved since 1989. Please describe the major transitions in your career. What have been the most important factors contributing to this evolution? (e.g., external forces, colleagues, personal ambitions, family, location, financial needs) |

| 6. What arrangements have you been able to or wanted to negotiate, both at work and at home, that may be atypical or special to enable you to do your job? (flex-time, sabbatical, additional support, etc.) |

| 7. Given your past experiences, what would you do differently in your next career phase? |

| 8. In the 1989 survey, most of the respondents spoke about the importance of being clear about “what you want.” We are curious whether you recall being very clear about your career path when you were a Clinical Scholar and how the clarity has changed for you over time? |

| 9. After reading your survey completed in 1989 what are your reflections in general? How have your goals changed since then? |

| 10. Is there anything else? What additional advice, helpful hints do you have for women with CSP or similar training looking for work now? |

CSP, Clinical Scholars Program.

Analysis

All survey responses were compiled and read independently by 3 readers (A.K., K.F., and N.B.), all of whom are graduates of the CSP but not subjects in the study. Themes in the data were identified and refined through an extensive interactive process of discussion, consensus building, and revision of a document summarizing our findings. This process went on until no new themes emerged. A comprehensive list of themes was applied to the data by 1 author (D.F.) who is not connected to the CSP in any way, using NVivo qualitative analysis software,6 and then reviewed by the other coauthors. These inductive and “emergent” rather than hypothesis-driven methods of qualitative data analysis are suggested by Grounded Theory.7

Through further iterations of consensus building, we developed a conceptual model to describe these data. Reasonable interrater reliability (κ statistics 0.35 to 1) was established for identification of major themes for 4 pairs of raters based on a random sample of 8 surveys. An abstract of the findings was sent to the 21 women with a request for comments and critiques. No major changes were recommended by the 6 participants who responded.

RESULTS

The average age of our respondents was 48 years (range: 45 to 56). Twelve had long-term monogamous relationships and 2 of the male partners were full-time stay-at-home parents. Three women were full professors, 10 were associate professors, and 2 had left academic medicine, they represented a cross-section of clinical disciplines. Eleven of the 16 women had children (average: 2.4 children; range: 1 to 3). The women who reported working full-time worked 54 to 80 h/wk, and those 3 who reported working part-time worked 28 to 49 h/wk. Total career grant funding obtained ranged from $0 to 2.2 million (mean: $816,700 for the 8 participants who reported on this topic in their CVs). Number of first authored papers published in peer reviewed journals ranged from 0 to 42 (mean: 29 for the 14 participants who sent us their CVs).

THEMES

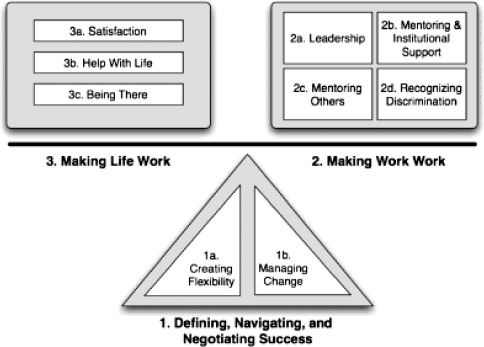

We ultimately identified 3 major themes. Conceptually the major theme we entitled Defining, Navigating, and Negotiating Success was the fulcrum of the other 2 major themes: Making Work Work and Making Life Work. In addition, several distinct subthemes were associated with each of the 3 major themes. From these themes and subthemes, we synthesized the model illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Themes, which emerged from these data.

Defining, Navigating, and Negotiating Success

Success was seen as having options while maintaining a consistent conscious awareness of and loyalty to one's own goals and priorities. These women defined success both by specific contributions to society (e.g., new discovery, new program that benefited a population, leadership in research) and their ability to attain and maintain personal and professional balance. A woman spoke of “[having] maintained a successful research career while working part-time.” Another woman stated, “My goals—do good, be happy—have always been pretty much the same.” Another defined success as the “opportunity to work in almost all possible sectors of the health care field” or “to help the most underserved populations.” This theme had 2 major subthemes.

Creating Flexibility

One important building block of success was flexibility. One woman who perceived herself as unsuccessful noted that she desired but did not have “flex schedules, part-time schedules, meetings at reasonable hours, [and] more realistic expectations.” Several described institutional cultures and employers as inflexible. For those women who considered themselves successful, the major strategies they employed to attain flexibility included early career establishment, obtaining outside funding, and hiring help. Despite difficulties with obtaining grants, most women savored the benefits of being self-funded, as was the case of the respondent with 3 children. She noted, “I can do research at any hour.” In addition, those who eventually were able to arrange more adaptable schedules with more flexibility attributed this achievement to an early established reputation as a creative, ambitious member of the department, “which gave the chair and our faculty confidence in my competence and hard work.”

Managing Change

Self-defined success was strongly affected by major personal life events. These included positive changes, such as the birth of a child, a new relationship, or relocation, as well as personal losses, such as the death of a loved one or a loss of an important relationship. These changes created “setbacks at work; less time to devote,” and the inability to advance a career. As one woman reported, “no publications during a four year period … After that, I had to regroup and focus on saving my career so I worked very hard to make up for lost time.” Career setbacks were common events in the lives of our subjects. For most, the accumulated experience of weathering these times led to empowerment, resiliency, and acceptance. As one participant put it, “[one of] the benefits of maturing is that I now realize that if I am patient through the difficult times, it will be better …”

Some of these women left academic careers and took positions with the government, in private practice, or industry. Their reasons included a partner needing to move, losing meaningful work, wanting to follow their passions, responding to a call to duty. One woman who went to work for private industry was pleasantly surprised to find that her “foundation in academic medicine and evidence-based medicine has made me a far better entrepreneur and medical doctor ….”

Making Work Work

This theme encompasses 4 subthemes, which represent the ways in which these individual women's characteristics interact with the particular work environments to maintain or upset life satisfaction.

Leadership

In general, these women kept their “eye on the prize,” as one woman put it, and continued to make choices that reflected the relative importance of the content of their work over long-term career considerations. They accepted leadership positions judiciously and explicitly through the prism of their values. Their reasons included being able to create “an opportunity to mentor researchers and develop a research agenda.” There was a level of awareness of what these roles entailed, as one respondent “turned down a number of chairmanship offers as well as directorships of large government agencies.” Because she went on to explain “I seek mental stimulation, intellectual challenge, and projects that will benefit people … titles bring demands that take away.” In addition, leadership roles in nonacademic fields allow women to achieve their own career goals. One woman raised the case of public health, which she liked because it is a “team sport” where she was able to accomplish her desire to “lead quietly and do my best to make sure that all members of the team share in the group's success.”

Mentoring and Institutional Support

In one case, a woman wrote “[I] was unable to mobilize the mentoring and senior support I needed to accomplish [my] goals.” Others agreed, stating that “Having a good boss makes or breaks your job satisfaction ….”

Although some thrived without it, most of our respondents needed effective institutional support. The essential role of mentoring to academic success was confirmed in this sample, as this woman states, “Mentors as [an] important special category of colleagues [have been] absolutely instrumental in my career evolution.” In some cases these relationships were complicated when respondents worked directly for their mentors. In our sample the women with mentors outside of their own institution perceived their mentoring relationships as more purely supportive. In the only explicit example of institutional support in these data, a woman acknowledged benefiting financially by “… being ‘flagged’ by the chancellors' offices as one of the many female faculty who were victims of gender discrimination with a salary level about 15% less than equal counterparts.” Although, lack of support is merely an obstacle for some and not a barrier to success, one wrote, “[I] have not received institutional support and have accomplished most of what I've accomplished despite my institution and not because of it.”

Mentoring Others

Each respondent mentioned the importance and joy of participating in the “development of younger colleagues” and “passing on research expertise and passion to … mentees.” But some perceived that their mentoring activities were not fully supported by their institutions, in one case a respondent reported being told “by my boss that I should do less advising and mentoring and should focus on things that will bring in money to support my salary.” Another respondent observed that she needed to be aware of the potential negative consequences of mentoring, because “women tend to do research more collaboratively and are more likely to be involved helping out on many other people's projects. Women mentors also tend to foster the interests of their trainees rather than directing these trainees to work on their own projects.”

Recognizing Discrimination

The majority of the sample bluntly acknowledged their workplaces were “unfriendly to women” and some suggested they were stuck where “nothing much has changed for the last 20 years … There are many more women at lower levels and very few in leadership positions and at higher levels and not for lack of talent.” From the perspective of one successful academic, “Lack of administrative experience is cited as a reason why women candidates are not considered for leadership positions, even at the lowest levels, while young men are given such jobs with no previous experience.” A majority of the participants perceived gender inequity. At least 3 women reported frank discrimination with serious consequences (e.g., the loss of an administrative position). One of these women expressed a “wish that some of my CSP mentors would have given me some early guidance about gender issues in the workplace. I was completely unprepared for them ….”

Making Life Work

This theme encompasses 3 subthemes, which represent the ways in which these individual women view their own satisfaction and its inextricable link with their home and personal lives.

Satisfaction

Ten of the 16 women stated that they were satisfied with their careers since leaving fellowship training. At the same time they were aware both of the personal cost of the struggle to balance their personal and professional lives and wary about the institutional barriers to the fulfillment of their potential and desires. One respondent, who described herself as satisfied and feeling fortunate for her job, wrote, “If I had known what my career would look like, I may not have chosen a career as a physician.”

Three of our respondents described their life satisfaction as “up and down.” One wrote, “Many times I feel I have no life. I have a job and I have kids, that's it. No room for myself …” Three of the women in our sample described themselves along the lines of “dissatisfied, unfulfilled, trapped.” The sources of the negative feelings included lack of mentoring support, feeling “locked in,” a particular individual in their workplace, or the lack of flexibility in their dual-career family.

Being There

These women put remarkable energy and ingenuity into being present physically and emotionally in the lives of their children, partners, friends and family, while continuing to be fully engaged in personally meaningful work. Our data set was replete with extremely detailed descriptions of our respondent's daily lives. One admitted that she “attempt[s] to spend as few hours at the workplace as possible …” but she believed she works “as many hours as my colleagues who choose to do all their work at the institution.” Family members have become part of work, where one respondent notes that her child “knows all of the people I work with, and feels a part of my work rather than separate from it.” Limit-setting appears important, as some strive to achieve balance by being “an efficient time manager” and setting “clear boundaries of what you will and won't do.”

Help with Life

Most of the respondents were in committed relationships, raising children with a partner who worked outside the home. Two women were the “breadwinners” and had husbands who were caring for young children full-time. Most of our respondents shared details about how they hire others to help at home, as it “frees me up to spend more time with my family.” After child care was no longer needed, respondents still hired the help of others to make life work. As one woman reported, “I don't have to spend precious weekend time running with my children to the drycleaners, the pharmacy, etc.” Others are still “waiting to see how this phase works out—taking on a major leadership role while dropping child care.”

DISCUSSION

These women, now at least 14 years out of academic fellowship, to varying degrees have achieved career success by traditional standards. Highly motivated and trained to achieve academic success, these women have done so by explicitly creating a personal vision of balance between work and home. The respondents who considered themselves most successful and satisfied made careful choices driven by their values, managed change effectively, established themselves early in their academic careers, and created the maximum flexibility in their daily lives.

We used purposive sampling, an iterative qualitative analysis method and incorporated “member checking” to maximize the trustworthiness of the inferences we made from these data. The independent analyst (D.F.) served as a “skeptical” reviewer, as the other 3 members of the analysis team were CSP graduates with experiences and values in common with our subjects.

The future of U.S. academic health centers relies on our ability to retain the intellectual capital of women. Although more women are entering the pipeline, this increased access for women to medical careers has not translated into the expected increase for women in influential leadership positions.8 Numerous studies in academic medicine and other settings have found that, even when men and women begin their first faculty appointment with the same preparation (i.e., board certification, advanced degrees, and research during fellowship training), women are less likely to receive office or lab space, protected time for research, or their first grant-supported position.9 Women also advance less quickly up the academic ladders and have lower salaries than similarly accomplished men.10 While gender discrimination during education and training continues to be a common experience, most young white women faculty assume a “level playing field” and therefore may not recognize discrimination unless it is grossly obvious.11 The cumulative career disadvantages of institutional discrimination and the continued unequal burden on women exerted by being the primary care giver for young children often deter the sustained productivity needed to be successful academically.12

Recent successful approaches to addressing these dilemmas have focused on providing women with those skills seen as needed for academic success.13 We increasingly recognize that the collegial workplace style women typically desire results in better worker performance as compared with an individually focused competitive model.14 Yet, criteria for academic success at most institutions still favor the second model as evidenced by promotion schedules, which at most institutions are still based on the career trajectories of young men not primarily responsible for home life and child rearing. Our respondents recognized this paradox and, to differing degrees, conformed to the system as needed while getting their own funding, working to establish and maintain mentoring relationships, finding work that is personally fulfilling, and trying not to compromise fundamental values. What is needed, and is being experimented with by some institutions, is a challenge to the culture that still defines success based on the trajectory of an academic who devotes herself completely to advancing her career during the early decades of work life and values independent work over interdisciplinary or team work.

Both the nature of our sample and the case series design of our study limit the ability to generalize our findings. Our model is not developmental in the tradition of the frameworks proposed by Erikson15 or Levinson,16 but rather more like that of Mary Bateson, among others, who have used similar case methods to study particular issues (i.e., discontinuity) in the lives of woman artists.17,18 These methods assume that each subject has different truthful versions of her life story that she will tell in different settings and at different times.17 Therefore, as long as the context is well understood there is value and validity to the stories told.

By traditional academic standards, our sample was composed of highly successful women who likely overrepresent women CSP graduates who stayed in academic medicine, and who felt motivated enough to spend the time to complete a survey, which was probing and personal. Because reporting the race or clinical discipline of our respondents could potentially identify individuals, we cannot address additional complexities and adversities experienced by minority faculty or address clinical discipline-specific issues. And of course, we can make no comments on how these findings may be the same or different for men in a similar training cohort. Larger studies of work life issues for both women and men across clinical disciplines outside of academic medicine are well underway.18 It would be valuable to follow up on work done in the 1980s4 to assess the current status of pay and status equity, work-life balance strategies including flex or part time, meaningful changes in criteria for promotion and tenure, and access to both funding for research and leadership positions for academics who may initiate research careers while working less than part time and/or at an older age.”19

CONCLUSIONS

To sustain the gains women in academia have made, it is imperative that female trainees are encouraged to make wise career-related decisions based on understanding their own personal definition of success. They must be mentored to plan for creating flexibility and to be prepared to weather unexpected change effectively. Academically oriented women, especially those with young children, who have less time for their work life, may feel pressured to shortchange themselves by adopting a job seeking strategy which pulls them away from work that interests them in order to gain greater short-term control but provides fewer opportunities for scholarly advancement. Early on, when investment in academic career development is most important, there is an attraction for women to clinical jobs with predictable time commitments but without the necessary support or mentoring for academic success. These data suggest that innovative approaches that challenge the prevailing pressure on career women to succeed on all fronts simultaneously, are needed (e.g., The Mary O'Flaherty Horn Scholars in General Internal Medicine20). A number of committed institutions have proven that it is possible to make substantial improvements in the development of women's careers using strategies that benefit all members of a faculty.21 To be effective such institutional innovations require taking a long term view, providing resources, such as effective mentoring regarding making the work-life balance satisfying and concrete help with conducting research with the goal of enhancing self-sufficiency early. Another set of policies must address maximizing flexibility in scheduling both on a daily and weekly basis and over the course of different career phases allowing periods of part time engagement in scholarly as well as clinical work. Discrimination of all types must be acknowledged and addressed.

In this work we begin to understand the ways in which work-life balance does not simply enhance work success—It is success.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dushanna Yoganathan Triola, MD, MPH, Marc Triola, MD, and Jo Anne Earp, ScD, for their substantial help in conceptualizing and editing the manuscript. We are also deeply grateful to our respondents who took time from their full and busy lives to contribute to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Latham EC. The Poetry of Robert Frost. New York: Henry Holt and Co; 1969. pp. 266–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickel J. Gender equity in undergraduate medical education: a status report. J Womens Health Gender Based Med. 2001;10:261–70. doi: 10.1089/152460901300140013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stobo JD, Fried LP, Stokes EJ. Understanding and eradicating bias against women in medicine. Acad Med. 1993;68:349. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levinson W, Kaufman K, Bickel J. Part-time faculty in academic medicine: present status and future challenges. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:220–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-3-199308010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Showstack J, Rothman AA, Leviton LC, Sandy LG. The Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars program. In: Isaacs SL, editor. To Improve Health and Health Care. Vol. VII. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Anthology. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 103–68. [Google Scholar]

- 6. NVivo, QSR, DataSense, LLC, 2004.

- 7.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morahan P, Bickel J. Capitalizing on women's intellectual capital in the professions. Acad Med. 2002;77:110–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine: glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273:1022–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:205–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr PL, Bickel J, Inui TS. Taking root in a forest clearing: a resource guide for medical faculty. Available at. [September 12, 2004.]. http://www.bumc.bu.edu/Dept/Content.aspx?PageID=8849&departmentid=42.

- 12.Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:532–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yedidia MJ, Bickel J. Why aren't there more women leaders in academic medicine? The views of clinical department chairs. Acad Med. 2001;76:453–65. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagly A. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull. 2003;129 doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson E. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson DJ, Levinson DJ, Levinson JD. The Seasons of a Woman's Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bateson MC. Composing a Life. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Working it Out; 23 Women Writers, Artists, Scientists and Scholars Talk about their Lives and Work. New York: Pantheon; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM career satisfaction study group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:372–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.im9908009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warde C. Work-family balance. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:343. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LP, Francomano CA, MacDonald SM, et al. Career development for women in academic medicine: multiple interventions in a department of medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]