Abstract

BACKGROUND

Men with erectile dysfunction (ED) often have low self-esteem, confidence, and sexual relationship satisfaction.

OBJECTIVE

We evaluated the impact of sildenafil citrate and its generalizability across cultures on self-esteem, confidence, and sexual relationship satisfaction in men with ED using the Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire.

DESIGN

Pooled analysis of 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose trials of sildenafil with identical protocols: 1 was conducted in the United States and the other in Mexico, Brazil, Australia, and Japan.

PATIENTS

Men ≥18 years old with ED.

MEASUREMENTS

The impact of treatment on psychosocial factors associated with ED was determined by patient responses to the SEAR questionnaire. Erectile function was determined using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and a global efficacy question. Successful sexual intercourse attempts were derived from event logs of sexual activity. Treatment effect sizes were calculated for all study outcomes.

RESULTS

Compared with patients who received placebo (n = 274), patients who received sildenafil (n = 279) reported significantly greater improvements (P<.0001) in self-esteem, confidence, sexual relationship satisfaction, and in all sexual function domains of the IIEF. Treatment effect sizes were large (range, 0.7 to 1.2) for all SEAR components, and improvement in psychosocial measures showed moderate to high correlations (range, 0.50 to 0.83, P<.0001) with improvement in erectile function, percentage of successful intercourse attempts, and global efficacy.

CONCLUSIONS

In men with ED from 5 different nations, sildenafil produced substantial improvements in self-esteem, confidence, and sexual relationship satisfaction. Improvements in these psychosocial factors were observed crossculturally and correlated significantly and tangibly with improvements in erectile function.

Keywords: erectile dysfunction, impotence, self-esteem, confidence, quality of life, relationship, psychometrics

The Massachusetts Male Aging Study reported that the prevalence of erectile dysfunction (ED) to some degree among men in the United States aged 40 to 70 years is approximately 52%1 and that the incidence of ED increases 5% per decade after the age of 40 years. A recent study of men from Brazil, Italy, Japan, and Malaysia showed that the prevalence of ED ranged from 18% to 54% for men aged 50 to 70 years,2 and a report of Finnish men showed that the prevalence of ED was substantially higher, ranging from 67% to 89% for men 50 to 75 years old.3 Worldwide, the prevalence of ED in men aged 40 to 80 years is estimated to be 13% to 28%.4 Although these studies employed different methodologies and cannot be compared with one another directly, they nonetheless show that the prevalence of ED is quite high. In addition, ED impacts a patient's and his partner's sexual life and is associated with depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.1,5

Sildenafil citrate (Viagra®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY) is the first-in-class phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor for the treatment of ED and has been prescribed to more than 20 million men in more than 110 countries.6 Accumulating evidence from numerous double-blind placebo-controlled and open-label trials suggests that sildenafil is well tolerated and effective for the treatment of ED of diverse etiology.7,8 Further, successful treatment of ED may be associated with improved measures of quality of life (QoL).5

However, correlations between successful ED treatment and changes in psychosocial measures have been difficult to determine because QoL is difficult to define and contains multiple components. Generic measures of QoL are not able to detect unique changes in men with ED, and ED-specific efficacy instruments fail to address relevant psychosocial domains such as self-esteem, confidence, and relationships.

The Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire (Appendix I available in the online version of JGIM) is a validated 14-item instrument that underwent rigorous development and validation using established psychometric principles. A psychometric evaluation of 98 men with ED and 94 age-matched controls showed discriminant validity of the SEAR for measuring self-esteem as well as relationship satisfaction and confidence.9 A 10-week, open-label study suggested that the SEAR questionnaire is responsive to effective ED treatment and is a valid instrument for detecting psychosocial gains from beneficial intervention.10 The SEAR was linguistically translated and culturally adapted to assess changes from baseline to end of treatment in relationships, confidence, and self-esteem. It is divided into 2 domains: Sexual Relationship (items 1 to 8) and Confidence (items 9 to 14). The Confidence domain has 2 subscales: Self-Esteem (items 9 to 12) and Overall Relationship (items 13 and 14). An Overall score (items 1 to 14) is calculated from the 2 domains. Response categories of each item are based on a 5-point Likert scale and are transformed onto a 0 to 100 scale, such that higher scores indicate a more favorable response:

|

In this report, we present the combined results from patients with ED from 5 different nations who were enrolled in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sildenafil. The objective was to verify treatment responsiveness and generalizability of the SEAR crossculturally and further establish the validity of assessing the psychosocial impact of successful treatment of ED.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

The data from 2 randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studies of 12-week duration was combined. Patients were enrolled in 1 study in the United States and in an identical study conducted in Mexico, Brazil, Australia, and Japan. The studies were approved by appropriate local Independent Review Boards, and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Sample Size

In the SEAR responsiveness study, a mean±SD change from baseline of 4.7±4.4 points was observed for the Self-Esteem subscale.11 Using these values in a regression analysis for each study, changes from baseline for the Self-Esteem subscale were estimated to be 4.57 and 2.19 for the sildenafil and placebo groups, respectively. A sample size of 75 in each group would have 90% power with a 0.05 2-sided significance level to detect a difference in means of 2.38 with a common SD of 4.44. Responsiveness of the Sexual Relationship domain and Confidence domain were similar to that of the Self-Esteem subscale. However, the analysis revealed less treatment responsiveness for the Overall Relationship subscale. Thus, the sample size was increased to have sufficient conventional power on this secondary efficacy measure. It was estimated that a sample size of 100 in each group per trial would have 80% power with a 0.05 2-sided significance level to detect a difference in means of 1.04 with the common SD of 2.61. Assuming that 80% of randomized patients contribute to the endpoint analyses, a total sample size of 126 patients per treatment group, or 504 for the pooled analysis, was selected to be randomized according to a computer-generated randomization code that assigned subjects in a 1:1 ratio.

Inclusion Criteria

Male patients aged ≥18 years of age were enrolled if they had a documented clinical diagnosis of ED (confirmed by a score of ≤21 on the Sexual Health Inventory for Men).12 Patients eligible to receive double-blind treatment were assigned a unique randomization number at baseline, and a computer-generated randomization code assigned patients in a 1:1 ratio to treatment with either sildenafil or placebo.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded if they had BP≤90/50 or ≥170/110 mmHg or had significant cardiovascular disease. Patients were excluded if they were taking nitrates, nitric oxide donors, or ritonavir, or if they had taken more than 6 doses of sildenafil before the screening visit.

Analyzed Groups

All patients who took at least 1 dose of study medication were included in the safety analysis. All patients who took at least 1 dose of study medication and who provided at least 1 postbaseline measurement were defined as the intent-to-treat population and included in the efficacy analysis.

Efficacy Measures

The primary study outcome was change from baseline to the end of treatment on the Self-Esteem subscale of the SEAR questionnaire.

Secondary measures were change scores on all other components of the SEAR and on standard efficacy measures of sexual function including the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)13 and the percentage of sexual intercourse attempts that were successful, determined from an at-home event log of sexual activity. Patients recorded important details of the sexual experience, such as dosage, timing, hardness of erections achieved, intercourse attempts, and success on their event log worksheets as soon as possible after each occurrence of sexual activity. In addition, a standard global efficacy question (GEQ), scored on an ordinal scale from 0 (no sexual activity) to 5 (almost always/always), was asked at the end of treatment: “When you took a dose of study drug and had sexual stimulation, how often did you get an erection that allowed you to engage in satisfactory sexual intercourse?”

Safety Measures

All volunteered or observed adverse events (AEs) were systematically recorded at week 2, 4, 8, and 12 of the study using the Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms (COSTART) preferred terminology. All AEs were listed by severity, body system, study medication dosage level, day of the onset, and resolution of the event.

Statistical Analysis

Change scores from baseline to week 12 were recorded for all items on the SEAR, the IIEF, and for the percentage of successful intercourse attempts. Differences in change scores from baseline were determined using an analysis of covariance model, controlling for baseline score and study, with the treatment group as the key explanatory variable. Partial Pearson's correlations (controlling for treatment and study) were obtained on changes in SEAR scores with changes in IIEF scores and changes in the percentage of intercourse attempts that were successful; SEAR scores at week 12 were correlated with the GEQ response at week 12. Mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) scores are reported for within-group changes and between-group comparisons.

Treatment effect sizes were calculated for all components of the SEAR, all domains of the IIEF, and for successful sexual intercourse attempts from the event log of sexual activity using the following calculation:

|

The difference in least squares (LS) mean change in SEAR scores between treatment groups was also divided by the square root of the mean square error (MSE) from the analysis of covariance model, which provided an estimate of the pooled SD of change scores adjusted for treatment and study.14

The GEQ was asked only at the end of treatment. Thus, no baseline data were available. The treatment effect size for the GEQ was calculated using end-of-treatment data and the pooled end-of-treatment standard deviation. Based on common benchmarks, effect sizes of 0.20 SD units are considered small, 0.50 medium, and 0.80 large.14

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

In total, 553 (US study, n = 253, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, and Japan study, n = 300) patients were enrolled and randomized to receive placebo (n = 274) or sildenafil (n = 279) from April 2002 to February 2003. Patients in each treatment group were well balanced for age, race, duration of ED, and etiology of ED, with no statistically significant differences noted between treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Placebo (n = 274) | Sildenafil (n = 279) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD age, y (range) | 55 ± 12 (23 to 81) | 56 ± 11 (25 to 83) | .18 |

| Race (%) | .73 | ||

| White | 57 | 54 | |

| Black | 15 | 15 | |

| Asian | 6 | 5 | |

| Other | 22 | 26 | |

| Mean ± SD weight, kg (range) | 85 ± 16 (53 to 148) | 86 ± 16 (47 to 142) | .62 |

| Mean ± SD duration of ED, y (range) | 4.3 ± 4.5 (0.1 to 34.6) | 4.4 ± 4.4 (0.1 to 36.6) | .83 |

| Primary ED etiology, n (%) | .41 | ||

| Organic | 113 (41) | 119 (43) | |

| Psychogenic | 55 (20) | 44 (16) | |

| Mixed | 106 (39) | 116 (41) |

ED, erectile dysfunction; SEAR, Self-Esteem And Relationship questionnaire.

Change Scores on the SEAR Questionnaire

Patients randomized to the sildenafil-treated group (vs placebo) reported significant (P<.0001) and substantially higher change scores from baseline on the Self-Esteem subscale (36.6; 95% CI, 33.1 to 40.2; vs 14.1; 95% CI, 10.5 to 17.7; Figure 1) and on all other components of the SEAR questionnaire: Sexual Relationship domain, Confidence domain, Overall Relationship subscale, and Overall score. The mean change in the Self-Esteem subscale score for patients who received sildenafil was 22.5 (95% CI, 17.7 to 27.4) points higher than the change reported by patients who received placebo.

FIGURE 1.

Mean change from baseline to end of treatment on SEAR components. Compared with patients who were randomized to receive placebo (n = 274, white bars), patients who were randomized to receive sildenafil (n = 279, gray bars) reported significantly higher scores on all components of the SEAR questionnaire. The height of the bars represents the mean, and the corresponding vertical line centered around the mean represents the 95% confidence interval (CI) within each treatment group. Difference in mean change between groups (95% CI) on SEAR components: Sexual Relationships domain, 22.9 (18.5 to 27.3); Confidence domain, 21.9 (17.3 to 26.6); Self-Esteem subscale, 22.5 (17.7 to 27.4); Overall Relationship subscale, 20.1 (14.9 to 25.2); Overall SEAR score, 22.4 (18.1 to 26.7). SEAR=Self-Esteem And Relationship questionnaire.*P<.0001 compared with placebo.

Treatment effect sizes (determined using baseline SD or the square root of the MSE, respectively) were large for improvements in the Self-Esteem subscale (effect sizes, 1.1 and 0.81), the Sexual Relationship domain (1.2 and 0.91), the Confidence domain (1.1 and 0.82), and the Overall score (1.2 and 0.90). The treatment effect size was medium to large for the Overall Relationship subscale (0.70 and 0.68, Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline, End of Treatment, Change Scores, and Treatment Effect Sizes for the SEAR, IIEF, Sexual Activity Event Log, and GEQ

| Placebo | Sildenafil | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Treatment | LS Mean Change ± SE | Baseline | End of Treatment | LS Mean Change ± SE | P Value | Effect Size | |

| SEAR | ||||||||

| Sexual Relationship domain | 39 ± 20 (37, 42) | 49 ± 29 (45, 52) | 10 ± 1.7 (7.0, 14) | 38 ± 20 (36, 41) | 71 ± 26 (68, 74) | 33 ± 1.6 (30, 36) | <.0001 | 1.2 |

| Confidence domain | 42 ± 21 (39, 44) | 54 ± 31 (50, 57) | 12 ± 1.8 (8.6, 16) | 42 ± 21 (39, 45) | 76 ± 25 (73, 79) | 34 ± 1.7 (31, 37) | <.0001 | 1.1 |

| Self-Esteem subscale | 39 ± 21 (37, 42) | 53 ± 32 (49, 57) | 14 ± 1.8 (11, 18) | 39 ± 21 (37, 42) | 76 ± 26 (72, 79) | 37 ± 1.8 (33, 40) | <.0001 | 1.1 |

| Overall Relationship subscale | 46 ± 28 (43, 50) | 56 ± 33 (52, 60) | 8.8 ± 1.9 (5.0, 13) | 48 ± 29 (44, 51) | 76 ± 28 (73, 80) | 29 ± 1.9 (25, 33) | <.0001 | 0.7 |

| Overall Score | 40 ± 19 (38, 42) | 51 ± 29 (47, 54) | 11 ± 1.6 (7.9, 14) | 40 ± 18 (38, 42) | 73 ± 25 (70, 76) | 33 ± 1.6 (30, 37) | <.0001 | 1.2 |

| IIEF | ||||||||

| Erectile Function domain | 12.8 ± 5.4 (12, 13) | 17.2 ± 8.6 (16, 18) | 4.8 ± 0.5 (3.8, 5.7) | 12.8 ± 5.0 (12, 13) | 23.5 ± 7.6 (23, 24) | 11.0 ± 0.5 (10, 12) | <.0001 | 1.2 |

| Orgasmic Function domain | 5.5 ± 2.7 (5.2, 5.8) | 6.6 ± 3.1 (6.2, 7.0) | 1.0 ± 0.2 (0.7, 1.3) | 6.0 ± 2.8 (5.6, 6.3) | 8.3 ± 2.5 (7.9, 8.6) | 2.5 ± 0.2 (2.2, 2.8) | <.0001 | 0.5 |

| Sexual Desire domain | 6.4 ± 1.9 (6.2, 6.7) | 7.0 ± 1.9 (6.8, 7.3) | 0.6 ± 0.1 (0.4, 0.8) | 6.6 ± 1.9 (6.4, 6.8) | 7.8 ± 1.7 (7.6, 8.0) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (1.1, 1.5) | <.0001 | 0.3 |

| Intercourse Satisfaction domain | 6.2 ± 2.4 (5.9, 6.5) | 9.1 ± 3.4 (8.7, 9.5) | 2.9 ± 0.2 (2.5, 3.3) | 6.4 ± 2.4 (6.1, 6.7) | 11.4 ± 3.4 (11, 12) | 5.2 ± 0.2 (4.8, 5.5) | <.0001 | 1.0 |

| Overall Satisfaction domain | 4.0 ± 1.8 (3.8, 4.2) | 5.6 ± 2.8 (5.3, 6.0) | 1.7 ± 0.2 (1.3, 2.0) | 4.2 ± 2.0 (4.0, 4.5) | 7.9 ± 2.4 (7.6, 8.2) | 3.8 ± 0.2 (3.5, 4.1) | <.0001 | 1.1 |

| Event Log | ||||||||

| Percentage of successful sexual intercourse attempts | 13 ± 25 (9.8, 16) | 39 ± 42 (34, 45) | 26 ± 2.7 (21, 32) | 12 ± 23 (9.2, 15) | 72 ± 39 (67, 76) | 59 ± 2.6 (54, 64) | <.0001 | 1.5 |

| GEQ | ||||||||

| Frequency of achieved erection | N/A | 2.7 ± 1.6 (2.5, 2.9) | N/A | N/A | 3.9 ± 1.5 (3.7, 4.1) | N/A | <.0001 | 0.8 |

The Event Log of Sexual Activity was used to determine the percentage of intercourse attempts that were successful. The GEQ asked “When you took a dose of study drug and had sexual stimulation, how often did you get an erection that allowed you to engage in satisfactory sexual intercourse?” and was administered at the end of treatment.

Data are mean ± SD (95% CI). P values are for difference in change from baseline to end of treatment between treatment groups.

[] Treatment effect sizes were determined using the difference in change from baseline scores and the pooled standard deviation at baseline. There were no baseline data for the GEQ. The treatment effect size for the GEQ was determined using end-of-treatment scores and the pooled standard deviation at the end of treatment.

GEQ, global efficacy question; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; LS, least squares; SEAR, Self-Esteem And Relationship questionnaire.

Change Scores on the IIEF Questionnaire

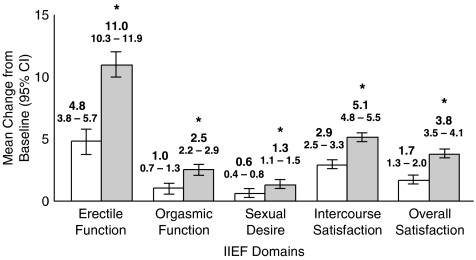

Patients who received sildenafil (vs placebo) also reported significant (P<.0001) increases from baseline on the Erectile Function domain (11.0; 95% CI, 10.0 to 11.9; vs 4.8; 95% CI, 3.8 to 5.7) and on all other domains of the IIEF questionnaire (Fig. 2): Orgasmic Function, Sexual Desire, Intercourse Satisfaction, and Overall Satisfaction. The mean change in Erectile Function scores for patients receiving sildenafil was 6.2 (95% CI, 4.9 to 7.5) points higher than the change reported by patients who received placebo. Treatment effect sizes were high for the EF, Intercourse Satisfaction, and Overall Satisfaction domains, and lower for the Orgasmic Function and Sexual Desire domains (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mean change from baseline to end of treatment in scores on IIEF domains. Compared with patients who were randomized to receive placebo (n = 274, white bars), patients who were randomized to receive sildenafil (n = 279, gray bars) reported significantly higher scores on all domains of the IIEF questionnaire. Domain items were summed, and higher scores indicated a more favorable response. The height of the bar represents the mean, and the corresponding vertical line centered around the mean represents the 95% confidence interval (CI) within each treatment group. Difference in mean change between groups (95% CI) on IIEF domains: Erectile Function, 6.2 (4.9 to 7.5); Orgasmic Function, 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0); Sexual Desire, 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0); Intercourse Satisfaction, 2.3 (1.7 to 2.8); Overall Satisfaction, 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6). IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function. *P<.0001 compared with placebo.

Change in Percentage of Successful Intercourse Attempts

The combined baseline percentage of sexual intercourse attempts that were successful was 13%. At week 12, patients who received placebo reported a 2-fold increase (27%; 95% CI, 21% to 32%) over baseline, whereas patients who received sildenafil reported a 5-fold increase (59%; 95% CI, 54% to 64%) over baseline. This between-group change in the percentage of sexual intercourse attempts that were successful represented a difference of 32% (95% CI, 26% to 40%, P<.0001) in favor of sildenafil, and the treatment effect size was very high (Table 2).

Frequency of Erections for Satisfactory Intercourse

At week 12, patients who received sildenafil (vs placebo) reported higher scores on the GEQ, indicating a significantly greater (P<.0001) frequency of erections that were satisfactory for sexual intercourse (3.9; 95% CI, 3.7 to 4.1; vs 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5 to 2.9). The mean frequency for patients receiving sildenafil was 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9 to 1.5) points higher than the frequency reported by patients receiving placebo; the treatment effect size was 0.8 (Table 2).

Correlation of SEAR Scores with Other Instruments

Correlations between changes in SEAR components and the Erectile Function domain of the IIEF ranged from 0.52 to 0.71 (P≤.0001, Table 3). Correlations of changes in SEAR components were also positive and statistically significant (P<.0001) with changes in other domains of the IIEF and with changes in the percentage of successful sexual intercourse attempts. In addition, correlations in SEAR components at week 12 and the frequency of satisfactory erections were high and statistically significant (P<.0001).

Table 3.

Pearson's Partial Correlation Coefficients* of SEAR Components with IIEF, Event Log, and GEQ

| SEAR | IIEF | Event Log† | GEQ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erectile Function | Sexual Desire | Orgasmic Function | Intercourse Satisfaction | Overall Satisfaction | |||

| 1. Sexual Relationships domain | 0.71 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.83 |

| 2. Confidence domain | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.78 |

| 2a. Self-Esteem | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.78 |

| 2b. Overall Relationship | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.66 |

| 3. Overall Score | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.83 |

All correlations were based on change scores from baseline (week 0) to end of treatment (week 12) except for the correlation between SEAR and GEQ, which was assessed at end of treatment.

All correlations were statistically significant (P<.0001).

Event log of Sexual Activity: Percentage of intercourse attempts that were successful.

GEQ (Global Efficacy Question): “When you took a dose of study drug and had sexual stimulation, how often did you get an erection that allowed you to engage in satisfactory sexual intercourse?”

IIEF, International Index of Erectile Dysfunction, SEAR, Self-Esteem and Relationship questionnaire.

Safety

In general sildenafil was well tolerated. The most frequent AEs (sildenafil vs placebo) were headache (13% vs 6%), rhinitis (5% vs 1%), dyspepsia (5% vs 2%), and flushing (8% vs 1%, Table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence of Adverse Events

| Placebo | Sildenafil | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 274 | 279 |

| Patients reporting AEs, n (%) | 88 (32) | 129 (46) |

| Most frequent (5% of patients in a treatment group) | ||

| Headache | 15 (6) | 35 (13) |

| Flushing | 3 (1) | 23 (8) |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (2) | 15 (5) |

| Rhinitis | 3 (1) | 13 (5) |

| Discontinuations due to AEs | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1) |

AEs, adverse events.

COMMENT

Normal sexual function is an important component of men's physical and psychological health, and the inability to perform sexually can have a negative impact on overall health and aspects of QoL.15 Indeed, the World Health Organization includes emotional and psychological well-being in its definition of health.16 Although the IIEF is considered the gold-standard instrument for measuring a patient's erectile functioning, research was needed on the psychosocial manifestations of ED and its treatment on relationships, confidence, and self-esteem. While existing disease-specific instruments have merit, they are limited psychometrically, lack an assessment of treatment responsiveness, are restricted to a single summary score, or do not address pertinent psychosocial issues.17–20 The SEAR questionnaire was developed to assess the ED-specific impact on psychosocial functioning and well-being related to sexual relationships, confidence, and particularly self-esteem.9,10

The Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors revealed that the factors associated with ED are similar across many cultures.4,21 Thus, it is reasonable to expect crosscultural improvement in psychosocial measures following successful treatment of ED. Data generated from the SEAR questionnaire confirm that as a patient's ED improves, so too do his confidence, relationships, and self-esteem. The correlations of change in SEAR scores with change scores in Sexual Desire on the IIEF were lower than the correlations of the other IIEF domains. It is likely that changes in psychosocial factors are more strongly related to functioning and satisfaction than to changes in sexual desire.

Conclusions on the SEAR questionnaire from the combined analyses across countries were maintained when examined by individual country and highlight the universal improvement in psychosocial function and well-being in men after successful ED treatment. Results by country showed a sizable and significant effect for each SEAR component, with noticeable changes in psychosocial function and well-being after successful ED treatment with sildenafil. While this study focused on the aggregate findings across countries (Mexico, Brazil, Australia, Japan, and the United States), the results suggest that psychosocial outcomes of ED treatment are discernible crossculturally. The involvement of self-esteem, confidence, and relationship satisfaction in overall health and well-being suggests that the SEAR should be used in conjunction with other treatment efficacy measures for a more complete assessment of the psychosocial impact of ED.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this combined analysis substantiate the psychometrically sound properties of the SEAR questionnaire and the robust gains in psychosocial functioning and well-being observed crossculturally—above and beyond placebo—that accompany beneficial treatment with sildenafil. The data obtained from these 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies extend the results to a larger set of populations, and indicate their generalizability across many cultures. However, separate analyses of the independent countries are in progress and will follow this larger study analysis. The SEAR questionnaire demonstrates sufficient sensitivity between treatment groups and across cultures, enhancing its validity, and specifically measures changes in relationships, confidence, and particularly self-esteem.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the study was provided by Pfizer Inc. Editorial support was provided by Carl Clay, PhD, of Complete Healthcare Communications Inc., and was funded by Pfizer Inc. Drs. Althof, O'Leary, Glina, and King are study investigators for Pfizer Inc. Drs. Cappelleri, Tseng, and Bowler are employees of Pfizer Inc.

Members of the U.S. and International SEAR study groups: Other members of the U.S. SEAR study group are Lawrence Alwine, Downingtown, PA; Albert A. Carr, Augusta, GA; Cully Carson, Chapel Hill, NC; Michael C. Collins, Hoover, AL; Raymond Costabile, Tacoma, WA; Francois Eid, New York, NY; Robert Feldman, Waterbury, CT; Jeffrey Geohas, Chicago, IL; Patricia Gilhooly, East Orange, NJ; Marc Gittelman, Aventura, FL; Evan Goldfischer, Poughkeepsie, NY; Louis J. Gringeri, Newtown, PA; Adrian J. James, New Orleans, LA; William Jennings, San Antonio, TX; Stephen Levine, Beachwood, OH; Robert S. Lipetz, Spring Valley, CA; Andrew McCullough, New York, NY; Marcia Miller, Gainesville, FL; Myron Murdock, Greenbelt, MD; Paul C. Norwood, Fresno, CA; Juan N. Otheguy, New Port Richey, FL; Harin Padma-Nathan, Beverly Hills, CA; Jacob Rajfer, Los Angeles, CA; John W. Robinson, Salt Lake City, UT; Ira Sharlip, San Francisco, CA; Norman Zinner, Torrance, CA.

Other members of the International SEAR study group are Joao Afif Abdo, São Paulo, Brazil; Carmita Helena Najjar Abdo, São Paulo, Brazil; Denilson Albuquerque, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Joaquim Claro, São Paulo, Brazil; Ronaldo Damaio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Walter Koff, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Arthur Beltrame Ribeiro, São Paulo, Brazil; Joao Roberto de Sá, São Paulo, Brazil; Jorge Sabaneeff, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Luis Otavio Torres, Belo Horizonte, Brazil; Fernando Vaz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Eric Wroclavski, São Paulo, Brazil; Raymundo Ballerteros, Aguascalientas, Mexico; David Calvo Dominguez, Durango, Mexico; Victor Alfonso Francolugo-Velez, Cuernavaca, Mexico; Luis Carlos Moy-Eransus, Mexico City, Mexico; Angel Orozco, Bravo, Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico; Carlos Pacheco Gahbler, Mexico City, Mexico; Ulises Perez-Toriz, Puebla, Mexico; Jose Arturo Rodriguez Rivera, Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico; Elias Zonana Sarca, Mexico City, Mexico; Dennis Cherry, Nedlands, WA, Australia; Douglas Lording, Malvern, VIC, Australia; Michael Lowy, Potts Point, NSW, Australia; Robert McLachlan, Clayton, VIC, Australia; Peter Sutherland, Adelaide, SA, Australia; Hitoshi Takamoto, Kurashiki-Shi, Okayama-Ken, Japan; Mineo Takei, Fukuoka-Shi, Fukuoka-Ken, Japan.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at www.blackwell-synergy.com

Sear Questionnaire.

Checklist of items included in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Shirai M, Ismail Bin Mohd Tambi M, Glasser DB. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2003;61:201–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiri R, Koskimaki J, Hakama M, et al. Prevalence and severity of erectile dysfunction in 50 to 75-year-old Finnish men. J Urol. 2003;170:2342–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000090963.88752.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:39–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althof SE. Quality of life and erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2002;59:803–10. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson CC., III Sildenafil: a 4-year update in the treatment of 20 million erectile dysfunction patients. Curr Urol Rep. 2003;4:488–96. doi: 10.1007/s11934-003-0031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carson CC, Burnett AL, Levine LA, Nehra A. The efficacy of sildenafil citrate (Viagra®) in clinical populations: an update. Urology. 2002;60(suppl 2B):12–27. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padma-Nathan H, Eardley I, Kloner RA, Laties AM, Montorsi F. A 4-year update on the safety of sildenafil citrate (Viagra®) Urology. 2002;60(suppl 2B):67–90. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappelleri JC, Althof SE, Siegel RL, Shpilsky A, Bell SS, Duttagupta S. Development and validation of the Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire in erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:30–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Althof SE, Cappelleri JC, Shpilsky A, et al. Treatment responsiveness of the Self-Esteem And Relationship questionnaire in erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2003;61:888–92. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The United States Self-Esteem and Relationship Questionnaire Study Group. O'Leary MP, Althof SE, et al. Self-esteem, confidence and relationship satisfaction of men with erectile dysfunction treated with sildenafil citrate: a multicenter, randomized, parallel group, double-blind, placebo controlled study in the United States. J Urol. 2006;175:1058–62. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. pp. 19–74. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonler M, Moon T, Brannan W, Stone NN, Heisey D, Bruskewitz RC. The effect of age, ethnicity and geographical location on impotence and quality of life. Br J Urol. 1995;75:651–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams JI. Ready, set, stop: reflections on assessing quality of life and the WHOQOL-100 (U.S. version). World Health Organization Quality of Life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:13–7. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrance GW, Keresteci MA, Casey RW, Rosner AJ, Ryan N, Breton MC. Development and initial validation of a new preference-based disease-specific health-related quality of life instrument for erectile function. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:349–59. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018482.71580.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swindle RW, Cameron AE, Lockhart DC, Rosen RC. The psychological and interpersonal relationship scales: assessing psychological and relationship outcomes associated with erectile dysfunction and its treatment. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:19–30. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000007459.48511.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa P, Arnould B, Cour F, et al. Quality of Sexual Life Questionnaire (QVS): a reliable, sensitive and reproducible instrument to assess quality of life in subjects with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:173–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonagh R, Ewings P, Porter T. The effect of erectile dysfunction on quality of life: psychometric testing of a new quality of life measure for patients with erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2002;167:212–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GSSAB. Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. [June 2, 2004]; Available at http://www.pfizerglobalstudy.com.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sear Questionnaire.

Checklist of items included in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.