Abstract

BACKGROUND

Specialty, work effort, and female gender have been shown to be associated with physicians' annual incomes; however, racial differences in physician incomes have not been examined.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the influence of race and gender on General Internists' annual incomes after controlling for work effort, provider characteristics, and practice characteristics.

DESIGN

Retrospective survey-weighted analysis of survey data.

PARTICIPANTS

One thousand seven hundred and forty-eight actively practicing General Internists who responded to the American Medical Association's annual survey of physicians between 1992 and 2001.

MEASUREMENTS

Work effort, provider and practice characteristics, and adjusted annual incomes for white male, black male, white female, and black female General Internists.

RESULTS

Compared with white males, white females completed 22% fewer patient visits and worked 12.5% fewer hours, while black males and females reported completing 17% and 2.8% more visits and worked 15% and 5.5% more annual hours, respectively. After adjustment for work effort, provider characteristics, and practice characteristics, black males' mean annual income was $188,831 or $7,193 (4%) lower than that for white males (95% CI: −$31,054, $16,669; P =.6); white females' was $159,415 or $36,609 (19%) lower (95% CI: −$25,585, −$47,633; P <.001); and black females' was $139,572 or $56,452 (29%) lower (95% CI: −$93,383, −$19,520; P =.003).

CONCLUSIONS

During the 1990s, both black race and female gender were associated with lower annual incomes among General Internists. Differences for females were substantial. These findings warrant further exploration.

Keywords: physician income, gender, race

Women have historically earned less than men have. In the United States, however, the disparity appears to be narrowing: the ratio of women's to men's median hourly wage increased from 63% in 1979 to 77% in 1999, purportedly because more women entered the work force, fewer women received minimum wages, and the real wages of men decreased.1

Female gender has also been shown to be associated with lower incomes among United States physicians, even after adjusting for work effort.2 Studies that also adjusted for physician age and specialty3–6 revealed similar income disparities, although one found that the combination of specialty status, personal data, and female Internists' less lucrative practice arrangements eliminated income differences.7 Less is known about the influence of race on physicians' incomes. In 1972, black physicians were reported to have different practice characteristics than their white counterparts8 and a request for analysis of geographic and functional distribution of black physicians has been made,9 but analyses of differences between black and white physicians' incomes have not been published.

Whether income disparities among physicians are attributable to race or gender is of interest for at least 2 reasons. First, blacks and females represent an increasingly large proportion of medical students,10 the residency workforce,11 and the practicing physician work force.10,12,13 For instance, between 1979 and 1999, the representation of medical school graduates increased from 5.1% to 7.7% for blacks and from 23.3% to 41.5% for women.10 Second, because black primary care physicians have been shown to be more likely to care for the underserved14,15 as well as medically indigent and sicker populations,16 it stands to reason that their annual incomes might suffer.

Our objective was to explore race and gender differences in the incomes of black and white General Internists, after adjusting for work effort, practice characteristics, and provider characteristics that are likely to influence physician incomes.

METHODS

Data Source

Between 1992 and 2001, the American Medical Association (AMA) conducted a regular survey of physicians that collected a broad variety of individual physician level data, including weeks and hours of practice, number of patient visits completed, provider characteristics, practice characteristics and physician incomes.17–24 Each year, the telephone-administered survey was conducted on a random sample of physicians from the AMA Masterfile that are eligible for the survey. After initial screening, federally employed physicians and physicians who spent <20 hours each week in patient care activities were excluded. A variety of procedures were developed to minimize nonresponse bias.24

Survey weights were derived by first dividing the AMA Physician Masterfile population and survey respondents into 200 cells defined by specialty, years since the respondent received an MD, AMA membership status, and board certification status. Unit response rates were constructed as the ratio of the number of physicians in the population to the number of respondents in each cell. An eligibility weight that divides the subset of the population for which eligibility is known into 40 cells (according to years in practice, AMA membership status, gender, and board certification) and calculates the proportion of physicians in each cell who are eligible was calculated. The overall weight applied for a given respondent is the product of the unit response weight and the eligibility weight.24

Sample

Although the survey had been conducted for much longer, this analysis was limited to data collected between 1992 and 2001 for 2 reasons. First, during the study period, the survey categorized physicians into different specialty groups in a way that allowed for the disaggregation of responses from General Internists from medical specialists with internal medicine training. We elected to focus on General Internists, whose work and level of pay would be more comparable. Second, these were the most recent data available for analysis, and therefore likely to be the most relevant to the currently practicing physician workforce.

A sequential process of eliminating survey respondents was used to ensure that all the physicians included in the analyses were comparable (see on-line appendix). This process left 1,435 white male, 43 black male, 253 white female, and 15 black female General Internists available for analysis. Using survey weights, these respondents represented 1,609 white male, 53 black male, 298 white female, and 21 black female General Internists.

Variables Proposed to Influence Physicians' Incomes

From the AMA data set, we extracted 3 types of independent variables that were likely to influence the dependent variable—net annual income:

Physician work effort. Hours worked is an important variable in analysis of physician incomes3–6,25; however, we believed that the number of visits a physician completes each year may also influence annual incomes. While private practice physicians typically bill based on patient visits completed, employed physicians are likely to have either quotas or incentive based production bonuses associated with patient visit volumes such that compensation methods are unlikely to be related to use of health services per person.26

Provider characteristics. When making gender comparisons of physician incomes, age has commonly been used as an adjustment factor.3–6 Over the working lifetime, incomes demonstrate an “inverted U” pattern27 that typically peaks near age 55 for primary care physicians.28 To dispel a concern that race or gender might influence the age at which a physician entered medical school, we incorporated the number of years that respondents had been practicing medicine into the analysis instead of physician age. In addition, because practice arrangements, such as having an ownership interest in the practice, have been associated with differences in annual income among physicians,7 we included whether the physician was an employee, as opposed to having an ownership interest in the practice, in the analysis. Finally, because board certification has been associated with higher incomes,29 we included board certification status as an independent variable in the analysis.

Practice characteristics. Physicians' incomes vary according to U.S. Census region defined practice location17–24; therefore, we collected information on the US census region in which the practice was located. Because physicians who practice in sparsely populated settings have been shown to have both lower30 and higher31 incomes, we categorized responding physicians' practice locations into 3 categories of metropolitan settings (<50,000 between 50,000 and 500,000 or >500,000). Finally, because black physicians disproportionately serve the medically indigent and those with relatively poor insurance, factors which have been hypothesized to decrease physicians' incomes,16 we incorporated variables which likely reflect those factors into the analysis: whether the practice provides Medicare services and the reported proportion of patients in the practice who are on Medicaid.

Calculated and Dummy Variables

We used the consumer price index to adjust reported net annual income to constant 2004 dollars. We multiplied the reported number of weeks worked in the last year by the total number of hours worked in the last week and the total number of visits completed in the last week to calculate the annual number of hours worked and the annual number of visits completed, respectively. Because of the “inverted U” relationship between number of years practicing medicine and annual incomes, we constructed dummy variables that categorized years practicing medicine into 5-year increments, from 0 to 5 years practicing through 40+ years practicing. While we used 5-year practice categories in the regression analysis, we aggregated years practicing into 10-year increments through 30+ years practicing for the purposes of demographic comparisons.

ANALYSIS

We used a linear regression model to determine the influence of race and gender on physicians' incomes, after adjusting for work effort and practice and provider characteristics. Within the regression model, we used dummy variables for each race-gender combination to calculate regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals in a model that used the independent variables detailed above and each respondent's consumer price index adjusted annual income as the dependent variable. Because physician incomes are log-normally distributed, we performed an additional analysis that used log-transformed data and had nearly identical results. For ease of interpretation, we report nontransformed results here. We used SPSS (Version 11.5, Chicago, IL) and survey weights for all analyses. This study was approved by Dartmouth Medical School's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, Hanover, NH (CPHS # 17,707).

RESULTS

After adjusting only for inflation, compared with white male General Internists, black men had mean annual inflation adjusted incomes that were $16,873 (8.6%) lower, white women had incomes that were $59,823 (31%) lower, and black women had incomes that were $82,489 (42%) lower (Table 1). While white female General Internists reported completing 22% fewer visits and working 12.5% fewer hours than their white male counterparts, black men and women reported completing 17% and 2.8% more visits and worked 15% and 5.5% more annual hours, respectively, than white men.

Table 1.

Comparison of Inflation Adjusted Income, Work Effort, Provider and Practice Characteristics of General Internists, by Race and Gender

| Inflation adjusted annual income (2004 dollars) | General Internists | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| White $196,024 | Black $179,151 | White $136,201 | Black $113,535 | |

| Physician work effort | ||||

| Total annual visits completed | 5,339 | 6,254 | 4,154 | 5,487 |

| Total annual hours worked | 2,905 | 3,341 | 2,542 | 3,064 |

| Provider characteristics | ||||

| Years in medical practice (mean) | 16.6 | 12.6 | 10.3 | 9.1 |

| < 10 y (%) | 30.2 | 56.6 | 54.8 | 61.9 |

| 10 to 19 y (%) | 39.3 | 30.2 | 38.3 | 38.1 |

| 20 to 29 y (%) | 21.0 | 3.8 | 6.4 | 0.0 |

| 30 y or more (%) | 9.6 | 9.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Ownership interest, and board certification | ||||

| Physician is an employee (%) | 36.4 | 50.0 | 62.0 | 68.2 |

| Physician is board certified (%) | 85.7 | 41.5 | 85.9 | 47.6 |

| Practice characteristics | ||||

| Census region of practice | ||||

| Northeast census region (%) | 23.5 | 15.1 | 27.9 | 28.6 |

| North Central census region (%) | 21.1 | 30.2 | 23.8 | 14.3 |

| Southern census region (%) | 34.4 | 47.2 | 27.5 | 57.1 |

| Western census region (%) | 21.1 | 7.5 | 20.5 | 0.0 |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Less than 50,000 population (%) | 7.2 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 0.0 |

| Population between 50,000 and 500,000 (%) | 25.5 | 7.5 | 18.7 | 28.6 |

| Population greater than 500,000 (%) | 67.4 | 83.0 | 74.8 | 71.4 |

| Service population | ||||

| Proportion of patients on Medicaid (%) | 9.3 | 22.4 | 11.3 | 36.6 |

| Proportion providing Medicare services (%) | 99.1 | 98.1 | 96.0 | 100 |

Black male and white and black female General Internists had practiced medicine for fewer years than white males. White men were more likely to have ownership interests in their practices. Black physicians of both genders were markedly less likely than their white counterparts to be board certified. A much higher proportion of both male and female black General Internists' patients were on Medicaid.

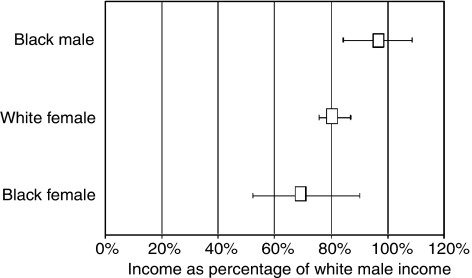

The regression model accounted for 19% of the variance in annual incomes (Table 2). Greater work effort was associated with higher incomes, and the model confirmed the anticipated inverted-U lifetime earnings curve. While board certification was associated with a higher income, not having an ownership interest in the practice, living in rural settings, and treating a higher proportion of Medicaid patients were associated with lower incomes. After adjustment for these variables, black males' mean annual income was $7,193 (4%) lower than that for white males (P =.6); white females' was $36,609 (19%) lower (P <.001); and black females' was $56,452 (29%) lower (P =.003) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Coefficients in the Regression Model that Used Inflation Adjusted Income as the Dependent Variable

| Coefficient | 95% confidence intervals | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician work effort | |||

| Total annual visits | $8.95 | $7.05 to $10.84 | <.001 |

| Total annual hours worked | $4.55 | $0.78 to $9.87 | .09 |

| Provider characteristics | |||

| Years in medical practice (5-10 years is referent) | |||

| Less than 5 years | $28,810 | $45,399 to $12,222 | .001 |

| 10 to 14 years | $8,992 | $1,573 to $19,557 | .10 |

| 15 to 19 years | $20,899 | $9,467 to $32,332 | <.001 |

| 20 to 24 years | $29,757 | $16,268 to $43,247 | <.001 |

| 25 to 29 years | $7,368 | $8,237 to $22,974 | .4 |

| 30 to 34 years | $19,091 | $415 to $38,597 | .06 |

| 35 to 39 years | $35,156 | $57,666 to $12,647 | .002 |

| 40 years or more | $47,991 | $89,989 to $5,993 | .03 |

| Ownership interest, and board certification | |||

| Physician is an employee | $18,780 | $27,027 to $10,533 | <.001 |

| Physician is board certified | $25,070 | $14,332 to $35,807 | <.001 |

| Practice characteristics | |||

| Census region of practice (Southern is referent) | |||

| Northeast census region | $4,056 | $14,127 to $6,014 | .4 |

| North Central census region | $5,783 | $4,471 to $16,036 | .3 |

| Western census region | $4,670 | $15,157 to $5,818 | .4 |

| Practice setting (population greater than 500,000 is referent) | |||

| Less than 50,000 population | $18,318 | $33,244 to $3,392 | .02 |

| Population between 50,000 and 500,000 | $3,111 | $12,114 to $5,891 | .5 |

| Service population | |||

| 1% increase in patient population on Medicaid | $258.69 | $547.51 to $30.13 | .08 |

| Proportion providing Medicare services | $10,176 | $22,013 to $42,366 | .5 |

| Race/gender characteristics (white male is referent) | |||

| Black male | $7,193 | $31,054 to $16,669 | .6 |

| White female | $36,609 | $47,633 to $25,585 | <.001 |

| Black female | $56,452 | $93,383 to $19,520 | .003 |

Adjusted R2 for the model =.19.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted annual incomes for black male, white female, and black female General Internists as a proportion of that for white male General Internists, with 95% confidence intervals.

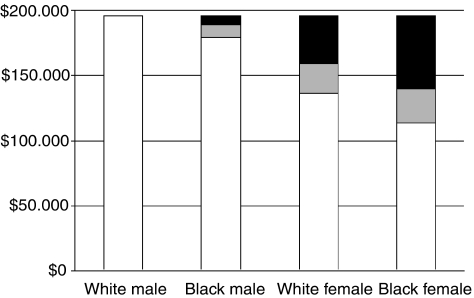

The adjustment for differences in work effort, provider characteristics, and practice characteristics, partially mitigated the initial differences in inflation adjusted annual incomes that were seen between white male and the other groups. While the income difference attributable to race and gender was modest for black male General Internists (Fig. 2), it was substantial for female General Internists of both races.

FIGURE 2.

Differences in income by race and gender. Grey represents the income difference accounted for by work effort, practice characteristics, and provider characteristics; black represents the income difference attributable to race and gender.

DISCUSSION

We examined provider and practice characteristics that were likely to be associated with physicians' annual incomes, revealed differences attributable to race and gender in those characteristics, adjusted net annual incomes for observed differences, and found that race and gender independently contribute to lower net annual incomes among office based General Internists. The expected reduction in annual income for black male General Internists was modest and not statistically significant; that for white and black female General Internists was substantial.

Our analysis revealed a strong association between higher annual incomes and work effort, particularly the number of patient visits completed. In addition, we found a strong association between being employed and having a lower mean annual income. Both findings are intuitive: patient visits are the mechanism for income generation and those with an ownership interest in the practice may be motivated to see additional patients. Our results were consistent with previous findings that black physicians are more likely than whites to care for the underserved and medically indigent14–16 and they support the suggestion that treating a larger proportion of Medicaid patients might adversely influence physicians' incomes.16

The association between higher annual incomes and board certification replicated findings from the early 1980s.29 The large difference between black and white General Internists' rate of board certification was surprising and difficult to explain. Black General Internists may be disinclined to pursue board certification, limited by the high costs, or may not do well on board certification tests, which may be a poor measure of subsequent performance for black physicians, as has been shown with other standardized tests.32

After correcting for differences in provider and practice characteristics, it was disconcerting to find that black and white female General Internists experienced annual incomes that were so heavily discounted compared with that of their male counterparts. While the anticipated 19% reduction in annual incomes found for white females was somewhat greater than that found in other studies that compared work-effort adjusted female to male physicians incomes,3–6 those analyses did not take into account the multiple provider and practice variables that we examined here. While limited by the small number of respondents, the 30% anticipated income differential between white male and black female generalists suggests an additive effect of race and gender on annual incomes for this group.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the study was limited by the methods used by the AMA in the conduct of the survey. While the number of black respondents to the survey was small, and a larger sample of black physicians would improve confidence in these findings, the ability to combine 10 years of data strengthened the study and offered a much more robust data set than would have been the case had fewer years of data been available. Second, some may be concerned that, during the time period that we examined, managed care penetration tripled33,34 and the Medicare Fee Schedule was implemented,35 both of which were expected to influence physicians' incomes. Conceivably, our findings could be spurious, simply reflecting increased numbers of female and black physicians during a time period of decreasing physician incomes. Although analyses using the same data sources have shown that General Internists' absolute incomes did not decline during the time period examined,25,36 we repeated our analysis, adding a year indicator to our regression model, and found that, although there was a mild decrease in inflation-adjusted income over the duration of the study, the overall findings were not different.

Finally, the study was inherently limited by the data available from the AMA survey. Although it would have been interesting to explore alternative explanations for the income disparities that we found, such as the proportion of charity care provided within black and white practices, respondents' educational debt burden, clinicians' levels of satisfaction with their practices, and even differences in the quality of primary care physicians' practices, the data that might answer these questions were not available. Indeed, the regression model accounted for only 19% of the variance in physician incomes. Clearly, additional factors that were not incorporated into the analysis are likely to influence expected physician incomes and might mitigate the differences found here.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that race and gender are independently associated with lower annual incomes among General Internists, and may be additive for black females. While salary differences between men and women may be common among nonprofessionals,1 it seems untoward that a profession that embraces equity as a cornerstone of medical practice quality37 should tolerate race or gender based inequity in pay. Black and female General Internists have achieved the same level of education, have made the same time commitment to training, and have experienced the same direct and opportunity costs required of such commitment as their male counterparts. Additional efforts to elucidate the underlying causes of any race or gender based salary differences are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by VA Health Services Research and Development Grant REA 03-098. Dr. Wallace is the recipient of a VA Health Services Research and Development Advanced Career Development Award. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or of the United States government. Dr. Weeks had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at http://www.blackwell.synergy.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Mishel L, Bernstein J, Schmitt J. The State of Working America, 2000–2001. An Economic Policy Institute Book. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langwell KM. Differences by sex in economic returns associated with physician specialization. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1982;6:752–61. doi: 10.1215/03616878-6-4-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohsfeldt RL, Culler SD. Differences in income between male and female physicians. J Health Econom. 1986;5:335–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr P, Friedman R, Moskowitz M, Kazis L, Weed H. Research, academic rank, and compensation of women and men faculty in academic general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:418–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02599159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker L. Differences in earnings between male and female physicians. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:960–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace AE, Weeks WB. Differences in income between male and female primary care physicians. J Am Med Women Assoc. 2002;57:180–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ness R, Ukoli F, Hunt S, et al. Salary equity among male and female internists in Pennsylvania. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:104–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson T. Selected characteristics of black physicians in the United States, 1972. JAMA. 1974;229:1758–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray LC. The geographic and functional distribution of black physicians: some research and policy considerations. Am J Public Health. 1977;67:519–26. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAMC Data Book. Statistical Information Related to Medical Schools and Teaching Hospitals. Washington, DC: The Association of American Medical Colleges; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brotherson SE, Rockey PH, Etzel SI. US graduate medical education, 2004–2005. JAMA. 2005;294:1075–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasko T, Seidman B, Birkhead S. Division of Survey Data Resources. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US: 2000–2001 Edition; p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens H. The intersection of race, gender, and primary care: results from the Women Physicians' Health Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:472–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu G, Fields SK, Laine C, Veloski JJ, Barzansky B, Martini CJ. The relationship between the race/ethnicity of generalist physicians and their care for underserved populations. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:817–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273:1515–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1992. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1993. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1994. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1995. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1996. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez M. Physician Marketplace Statistics, 1997/98. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, Center for Health Policy Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P, Thran S. Physician Socioeconomic Statistics, 1999–2000. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Center for Health Policy Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wassenaar J, Thran S. Physician Socioeconomic Statistics, 2000–2002. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Center for Health Policy Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Time and money: a retrospective evaluation of the inputs, outputs, efficiency, and incomes of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:944–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conrad DA, Maynard C, Cheadle A, et al. Primary care physician compensation method in medical groups: does it influence the use and cost of health services for enrollees in managed care organizations? JAMA. 1998;279:853–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polackek SW, Siebert WS. The Economics of Earnings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Wallace MM, Welch HG. A comparison of educational costs and incomes of physicians and other professionals. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1280–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker ER, Culler S, Ohsfeldt R. Impact of board certification on physician practice characteristics. J Med Edu. 1985;60:9–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weil TP. Attracting qualified physicians to underserved areas. Part 2. Pay physicians more to practice in underserved areas. Physician Exec. 1999;25:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reschovsky JD, Staiti AB. Physician incomes in rural and urban America. Issue Brief/Center for Studying Health System Change. 2005;92:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen WG, Bok DC. The Shape of the River. Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadley J, Mitchell JM. The growth of managed care and changes in physicians' incomes, autonomy, and satisfaction, 1991–1997. Int J Health Care Financ Econom. 2002;2:37–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1015397413797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadley J, Mitchell J. HMO penetration and physicians' earnings. Med Care. 1999;37:1116–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy J, Borowitz M, McNeill S, London W, Savord G. Understanding the Medicare Fee Schedule and its impact on physicians under the final rule. Med Care. 1992;30:80–NS93. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199211001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Medicare payment changes and physicians' incomes. J Health Care Finance. 2002;29:18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berwick DM. A user's manual for the IOM's ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Affairs. 2002;21:80–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.