SYNOPSIS

Since 1995, the New York State (NYS) Adult Hepatitis Vaccination Program has promoted adult hepatitis B vaccination for those receiving sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic services. An average of 6,333 doses was administered annually from 1995 to 1999. By 2000, only 15 of 57 county STD programs in NYS outside of New York City participated. From 2000 to 2005, efforts to enroll county health departments and others included outreach, provision of hepatitis A and B vaccine, materials and training, and new collaborations. All 57 counties now participate. From 2000 to 2005, the number of settings offering hepatitis vaccination increased from 57 to 119. Sites include STD clinics; jails; migrant, Indian health, and college health centers; and methadone clinics. More than 125,000 doses of hepatitis A and B vaccine were administered from 1995 through 2005, with annual increases up to a high of 21,025 doses in 2005. Intensive promotion expanded hepatitis vaccination to all county STD clinics and other settings where high-risk adults can be vaccinated.

Despite availability of effective vaccines and guidelines for vaccination of high-risk adults against hepatitis A and B,1–3 national vaccination goals have yet to be achieved,4 and the incidence of hepatitis A and B among adults remains unacceptably high.5,6 Integration of hepatitis vaccination in settings serving those at highest risk is challenging, and a lack of dedicated federal funding for support of vaccines for adults is a significant barrier.5,7–11 Missed opportunities to vaccinate adults in various settings abound.5,7–10 This article describes a statewide program to provide hepatitis A and B vaccination to adults at high risk.

Since 1995, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) Adult Hepatitis Vaccination Program (AHVP) has focused on vaccinating high-risk adults. The AHVP, directed by the NYSDOH Hepatitis B Coordinator, provides outreach, education, and technical assistance to providers, health departments, and hospitals regarding hepatitis vaccination and other hepatitis-related issues. Assistance comes from data-entry and support staff, as well as four regional adult immunization coordinators. The Immunization Program's Vaccine Unit distributes vaccines to vaccination sites. Each of the 57 local health departments (LHDs) outside of New York City (NYC) has an immunization coordinator who promotes vaccination of high-risk adults and coordinates local vaccination efforts. The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) has offered hepatitis vaccination at all public sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics in the five counties of NYC since 2000.

With dedicated state funding for the purchase of vaccine for adults, hepatitis B vaccination was initiated in 1995 in public STD clinics, in collaboration with the NYSDOH Bureau of STD Control (BSTDC). Multiple factors, including competing priorities, concern over the stability of funding for vaccine, and feasibility issues, resulted in slow enrollment by the 57 NYS counties outside of NYC. As of 2000, only 15 counties (26%) had enrolled, and the AHVP and BSTDC intensified efforts to enroll all counties in the program. In early 2002, the availability of Twinrix® (combination hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine) and encouragement of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to integrate adult vaccination with other public health programs provided added impetus. The AHVP also wanted to reach other settings serving adults at high risk with hepatitis A and B vaccine. This article discusses a NYSDOH initiative during 2000–2005 to promote hepatitis vaccination.

METHODS

NYSDOH, in collaboration with multiple partner organizations, made a substantial, sustained effort over five years to promote vaccination of high-risk adults in STD clinics and other settings. Specific strategies included provision of vaccine, expanding LHD involvement, extending the AHVP to other settings, materials development, and training.

In addition to purchase of single antigen hepatitis B vaccine, the AHVP expanded to include Twinrix® and hepatitis A vaccine in 2002, and guidance protocols and vaccination fact sheets were developed.12 In 2003, the NYSDOH Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) Institute and the AHVP formed a Hepatitis A and B Work Group, inviting BSTDC staff and colleagues from the NYS Office on Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) and the NYS Department of Correctional Services to participate.

Strategies to enroll remaining county STD clinics included a joint letter from the AHVP and BSTDC, telephone calls from the Hepatitis B Coordinator and regional DOH staff, letters, and meetings at LHDs. LHDs were encouraged to provide free vaccines to all high-risk adults and adolescents seeking services in LHD STD clinics, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) counseling and testing programs, tuberculosis (TB) clinics, and adult immunization clinics.

In 2001, the NYSDOH AIDS Institute approached the AHVP to discuss vaccination needs of men who have sex with men (MSM). While some MSM attend public STD clinics, many do not. Following the AIDS Institute's distribution of a letter and resource packet to HIV prevention providers statewide explaining the CDC's 2002 STD Treatment Guidelines,2 meetings were held with the AHVP to explore expanding access to vaccine for MSM and others receiving HIV/AIDS services. Because many HIV prevention providers do not administer vaccine, they were encouraged to contact LHDs for information on how to refer individuals for free vaccine. LHDs were encouraged to reach out to HIV prevention programs. Guidance for integrating hepatitis education and information into HIV programs and services and how to obtain free materials on viral hepatitis was provided.13

During 2003, a pilot program provided state-funded hepatitis vaccines to 10 LHDs to vaccinate jail inmates. Over the next two years, other LHDs expressed interest in vaccinating jail inmates, despite barriers (e.g., lack of qualified personnel, lack of buy-in from jail administrators). Additional LHDs joined the initiative, raising the total to 30 LHDs involved in the program by the end of 2005. During 2005, 5,526 doses of hepatitis A and B vaccine were administered by LHDs to jail inmates.

The AHVP recognized that further reduction of hepatitis A and B infection, transmission, and eventual elimination required reaching other groups of adults at risk. Collaborations with other NYSDOH programs made it possible to engage local providers in adult vaccination activities. Working with the Migrant Health Program in 2003, hepatitis and other adult vaccines were provided to three federally qualifying migrant health centers, and outreach to additional programs serving migrant and seasonal farm workers ensued. In 2004, vaccine was provided to health centers serving Native Americans through the Indian Health Program. Ongoing collaboration with the BSTDC offered the opportunity to reach at-risk young adults through college health services participating in the BSTDC's Infertility Prevention Project's chlamydia screening program. Additionally, in 2003, hepatitis vaccines were provided to methadone maintenance treatment programs in Albany, Nassau, and Suffolk counties.

Since 2003, Hepatitis A and B Work Group members have collaborated on materials and training initiatives. For example, a 21-question, self-administered integrated risk-assessment tool was developed in English and Spanish to collect information regarding behaviors that may put the client at risk of STD, HIV, or hepatitis infection. Clients may choose not to disclose specific risk(s), as it could be a barrier to vaccination. Instructions and an answer guide for clinic staff were also developed.14

The “NYS Viral Hepatitis Strategic Plan,” released in June 2004, includes recommendations for adult hepatitis vaccination.15 Members of the Hepatitis A and B Work Group developed and implemented a format to track the status of recommendations and actions taken.

New consumer education materials became available in 2005. A total of 1,237 copies of “Know more about Hepatitis A and B”—a poster that provides information on the risks of hepatitis A and B and encourages people to get vaccinated—were distributed to health and human service providers statewide. “Hepatitis A—Know the risks. Get vaccinated” and “Hepatitis B—Know the risks. Get vaccinated” magnets provide information on the risks of hepatitis and encourage vaccination. During 2005, 8,035 magnets were distributed. Information about hepatitis A and B, available online at the NYSDOH Viral Hepatitis home page, received 13,114 hits from July 1, 2005, through June 30, 2006.16

During 2002, five regional workshops on integration of hepatitis prevention in high-risk settings were conducted in collaboration with the BSTDC. During 2004–2005, a total of 623 training programs covering STD, HIV, and hepatitis A, B, and C infection—some sponsored by the BSTDC and others by the AIDS Institute—reached 6,563 participants, including physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, physician assistants, HIV test counselors, other health and human professionals from state and county health departments, hospitals, community health centers, county jails, juvenile detention centers, state prisons, substance abuse treatment programs, community-based HIV/AIDS organizations, and others. These training programs helped promote the use of hepatitis vaccines in a variety of settings where adults at high risk seek services.

In September 2003, the AIDS Institute Office of the Medical Director received a competitive award from the CDC to develop, evaluate, and disseminate a national training curriculum on viral hepatitis. The training addresses basic information about hepatitis A, B, and C, with emphasis on integration of viral hepatitis services in HIV/AIDS programs, public health and STD programs, correctional settings, and substance use programs.17 The AHVP participated in development and piloting of the curriculum. Other partners include the OASAS, the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America (ACRIA), and the NYC DOHMH. These trainings helped promote vaccination of high-risk adults by preparing providers to offer vaccination services.

RESULTS

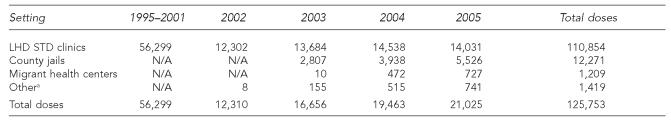

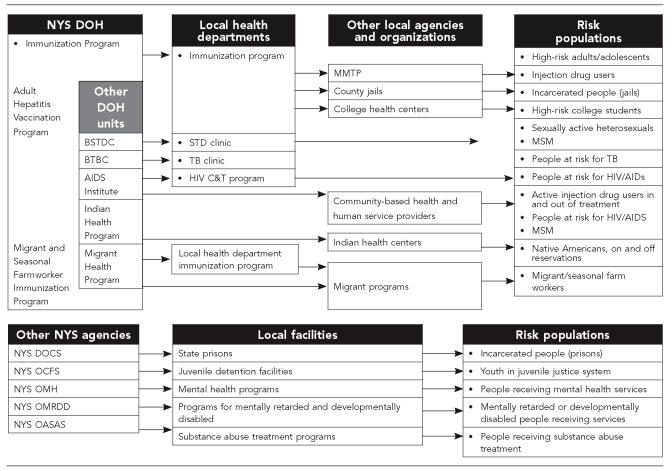

The number of sites at which adult hepatitis vaccination was offered in NYS more than doubled between 1995 and 2005, from 57 to 119 settings; the number of participating STD clinics increased from 17 to 57. By 2004, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and Twinrix® vaccines were available from all 57 LHDs. In two years, the number of jails offering vaccination tripled, from 10 to 30, and the number of participating migrant health centers increased from six to 10. By the end of 2005, vaccines were provided at 22 migrant sites, with more than 1,200 doses of hepatitis vaccines administered. Hepatitis vaccines are being provided to five state-funded Indian Health Centers, four methadone maintenance treatment programs, and eight college health centers. The number of doses of hepatitis vaccine administered increased from a mean of 8,043 doses per year from 1995 to 2001 to 21,025 doses during 2005 (the Table). Collaborations have extended the reach of the AHVP from STD clinics to a broad array of settings reaching those with various risk factors (Figure 1).

Table.

Doses of Hepatitis A and B vaccine administered by setting, New York State, 1995–2005

Other includes college health centers, substance abuse treatment programs, Indian Health Centers, and other LHD clinics (e.g., tuberculosis, adult immunization).

LHD = local health department

STD = sexually transmitted disease

Figure 1.

Reaching adults at high risk: a coordinated systems approach

- BSTDC = Bureau of STD Control

- BTBC = Bureau of TB Control

- DOCS = Department of Correctional Services

- MMTP = Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program

- MSM = men who have sex with men

- OASAS = Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services

- OCFS = Office of Children and Family Services

- OMH = Office of Mental Health

- OMRDD = Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities

- NYS DOH = New York State Department of Health

- STD = sexually transmitted disease

- TB = tuberculosis

- HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

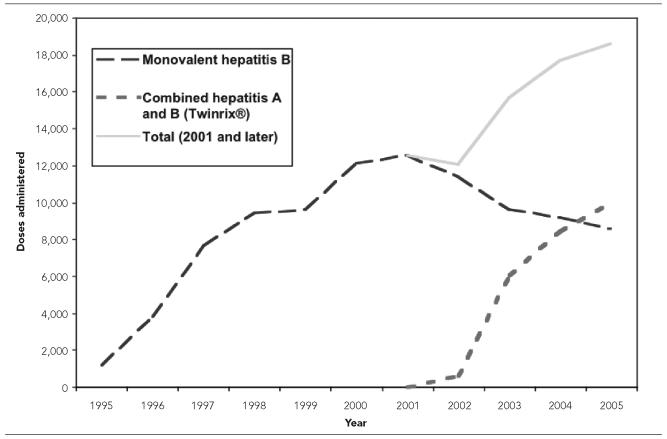

More than 125,000 doses of hepatitis A and B vaccine, given as monovalent or Twinrix® vaccine, have been administered since 1995, including 21,025 doses administered during 2005. Aggregate data are collected, limiting the ability to calculate vaccination completion rates and percent of population vaccinated. Figure 2 illustrates a steady increase in the number of hepatitis B vaccine doses administered, given as monovalent or Twinrix® vaccine in public STD clinics and jails from 1995 to 2005. Twinrix® vaccine has become the predominant vaccine, with 10,034 doses and 8,562 doses of monovalent hepatitis B vaccine administered in 2005. Similarly, a significant uptake of hepatitis A vaccine occurred in just three years, from 272 doses of monovalent hepatitis A vaccine in 2002 to 1,699 doses in 2005.

Figure 2.

Doses of hepatitis B vaccine, by vaccine type, administered in public sexually transmitted disease clinics and county jails: New York State, 1995–2005

CONCLUSIONS

Although hepatitis vaccination for adults is now well established in STD clinics statewide, startup was slow and required active involvement of the BSTDC. Collaborating with partner organizations, the AHVP gained access to a broad spectrum of people at high risk.5

Making hepatitis vaccines available to providers is an important component of a comprehensive adult hepatitis vaccination program. Getting busy providers to administer vaccine or make referrals requires promotion, follow-up, training, and materials, and building a comprehensive program requires a long-term commitment and a continued focus on the needs of individuals at risk. Partnerships can lead to new models of service delivery. For instance, in late 2005, the AIDS Institute arranged a meeting between the OASAS and the AHVP to discuss strategies for vaccination of adults receiving substance abuse treatment services. By early 2006, the AHVP and OASAS were linking substance abuse treatment programs and LHD adult immunization programs. A pilot program in two counties is underway and being evaluated for possible expansion to other counties. Another initiative involving AHVP, BSTDC, the AIDS Institute, the NYS Department of Correctional Service, and the NYS Commission of Correction is expected to improve the transfer of vaccination information when inmates move from jails to prisons, between prisons, and between jails.

Funding for the implementation of Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations for screening and vaccination of all people at risk for hepatitis A and B is needed to supplement existing local resources and make needed resources available in jurisdictions without existing capacity. It would benefit both insurers and patients if full coverage for hepatitis A and B vaccination were available to adults who indicate that they are at risk, without requiring them to disclose specific risks. Prevention education and interventions are crucial, and educational materials suitable for diverse populations are needed. Existing guidance is available to inform health departments about challenges and strategies to overcome them.7,17

“Eliminating Hepatitis: A Call to Action” (April 2006), a plan by the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, underscores the urgent need to discover and resolve barriers to vaccination of adults at risk for hepatitis A and B.18 The experience in NYS demonstrates that hepatitis vaccinations can be provided in a variety of settings where adults at high risk seek services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank other members of the Hepatitis A and B Work Group, specifically Jay Cooper, Richard Cotroneo, Colleen Flanigan, Marilyn Kacica, Bill Karchner, Linda Klopf, Geraldine Naumiec, Maxine Phillips, Jeff Rothman, and Felicia Schady.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part II: immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-16):1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC (US) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC (US) Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-7):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services (US) 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [cited 2006 May 26]. Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. Also available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/pdf/uih/2010uih.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein ST, Alter MJ, Williams IT, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K, et al. Incidence and risk factors for acute hepatitis B in the United States, 1982-1998: implications for vaccination programs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:713–9. doi: 10.1086/339192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC (US) Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. [cited 2006 May 22]; Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/resource/dz_burden.htm.

- 7.National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (US) Washington, DC: NASTAD; 2004. [cited 2006 Aug 8]. Viral hepatitis and HIV/AIDS integration: a resource guide for HIV/AIDS programs. Also available from: URL: http://www.nastad.org/Programs/viralhepatitis. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich JD, Ching CG, Lally MA, Gaitanis MM, Schwartzapfel B, Charuvastra A, et al. A review of the case for hepatitis B vaccination of high-risk adults. Am J Med. 2003;114:316–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, McFarland W, Shehan D, Ford W, et al. Two decades after vaccine license: hepatitis B immunization and infection among young men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:965–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershey JH, Schowalter L, Bailey SB. Public health perspective on vaccine-preventable hepatitis: integrating hepatitis A and B vaccines into public health settings. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 10A):S100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handsfield HH. Hepatitis A and B immunization in persons being evaluated for sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 10A):69S–74S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New York State Department of Health. Hepatitis vaccine information. [cited 2006 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/vaccine.htm.

- 13.New York State Department of Health. Letter to HIV prevention providers. [cited 2006 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/aids/hepatitis/hepletter.htm.

- 14.New York State Department of Health. Integrated risk questionnaire materials. [cited 2006 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/questionnaire.htm.

- 15.New York State Department of Health. Viral hepatitis strategic plan. [cited 2006 May 22]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/strategic/index.htm.

- 16.New York State Department of Health. Viral hepatitis: the A, B, Cs of viral hepatitis. [cited 2006 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/

- 17.New York State Department of Health. The National Viral Hepatitis Training Center. [cited 2006 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/aids/training/currentevents.htm.

- 18.National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (US) Eliminating hepatitis: a call to action. [cited 2006 May 22];April 2006 Available from: URL: http://www.nvhr.org/pdf/NVHR_CalltoAction.pdf.