SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

Hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for clients of sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics. The Healthy People 2010 goal is for 90% of STD clinics to offer hepatitis B vaccine to all unprotected clients. This report describes hepatitis B vaccination trends in six STD clinics in the United States and discusses implications for policy and practice.

Methods.

We conducted a retrospective study in six STD clinics to evaluate hepatitis B vaccination. We collected data on client visits and hepatitis B vaccinations for the period 1997–2005. To compare clinics, we calculated vaccination rates per 100 client visits. We interviewed staff to explore factors associated with hepatitis B vaccination trends.

Results.

STD clinic client visits ranged from 2,883 to 23,109 per year. The median rate of hepatitis B vaccination was 28 per 100 client visits. Vaccination rates declined in all six clinics in later years, which was associated with eligibility restrictions caused by fiscal problems and increasing levels of prior vaccination. The median rate of vaccine series completion was 30%. Staff cited multiple provider- and client-level barriers to series completion.

Conclusions.

This study shows that STD clinics can implement hepatitis B vaccination and reach large numbers of high-risk adults. Adequate funding and vaccine supply are needed to implement current federal recommendations to offer hepatitis B vaccine to adults seen in STD clinics and to achieve the Healthy People 2010 objective.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is vaccine-preventable. An estimated 1.25 million Americans have chronic HBV infection, which can lead to lifelong infection, cirrhosis of the liver, liver failure, liver cancer, and death.1 The primary routes of HBV transmission in the U.S. are through sexual contact with an infected partner and percutaneously via contaminated needles or syringes (e.g., illicit injection drug use).

Of the total number of people with acute HBV infection reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 1982 to 1998, 36% had been previously treated for a sexually transmitted disease (STD).2 Recognizing the public health importance of hepatitis B vaccination, CDC's 2002 STD treatment guidelines recommended for the first time that all unvaccinated adults being seen in STD clinics should be considered at high risk for HBV infection and receive hepatitis B vaccination.3 This recommendation was reinforced in CDC's 2006 STD treatment guidelines and 2006 strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus in the United States.4,5 Furthermore, one of CDC's Healthy People 2010 objectives recommends that 90% of public STD clinics nationwide offer hepatitis B vaccination to all clients.6 Although there has been some progress in vaccinating clients of public STD clinics,7 as of 2001, only 26% of STD clinic program managers reported that all clients attending these clinics were eligible for vaccination—a notable increase from 9% in 1997, but far short of the 90% goal.8

This article examines trends in hepatitis B vaccination from as early as 1997 to 2005 in six STD clinics in the United States that were committed to integrating viral hepatitis prevention services—including hepatitis A and B vaccination and hepatitis C virus (HCV) counseling, testing, and referral—with existing clinical services. It also provides insights from senior STD clinic staff on hepatitis B vaccination efforts and trends.

METHODS

We used a retrospective study design to evaluate the extent of hepatitis B vaccination in six participating, publicly funded STD clinics. The six clinics (and the year in which they began hepatitis B vaccination) were San Francisco (1989); New York City (NYC) (1995); San Diego (1998); Denver (1999); and two clinics in Illinois: DuPage County (2000) and Winnebago County (2001). One of the clinics (San Diego) received funding from CDC for hepatitis B vaccination beginning in 1998. This clinic and four others received CDC funding for implementing or expanding viral hepatitis services from 2000 to 2003. These funds were used to integrate hepatitis A and B vaccinations and HCV counseling, testing, and referral into STD clinics, HIV counseling and testing sites, drug treatment facilities, and jails. The San Francisco STD clinic did not receive CDC funds for hepatitis integration, but had introduced hepatitis B vaccination in the late 1980s.

We obtained hepatitis B vaccination data from 1997 to 2005, collecting annual numbers of hepatitis B vaccinations from each clinic, including doses of monovalent hepatitis B vaccine and combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (hereafter referred to as “combined vaccine”). To compare data from STD clinics with substantial differences in numbers of clients, we calculated hepatitis B vaccination rates per 100 client visits. Client visits included first visits and additional visits by some individuals over the course of a year. Because client-level data were unavailable, we calculated proportions of third doses of hepatitis B vaccine relative to the number of first doses to estimate the proportion of clients who completed the three-dose vaccination series. We excluded start-up years with low productivity or with less than six months of data.

We interviewed a total of nine key informants (e.g., clinic manager, nurse supervisor) from the six STD clinics to identify factors that could help explain hepatitis B vaccination trends. We interviewed two key informants from the NYC clinic and three key informants from the two Illinois clinics, one of whom was a state employee who oversaw integration at the local level. One staff member at each of the remaining clinics was interviewed. We developed an interview guide that included a standardized list of open-ended questions. The main topics covered included changes in funding, client or staff characteristics, infrastructure, and eligibility for hepatitis B vaccination. The analysis focused on identifying patterns and common themes across respondents.

RESULTS

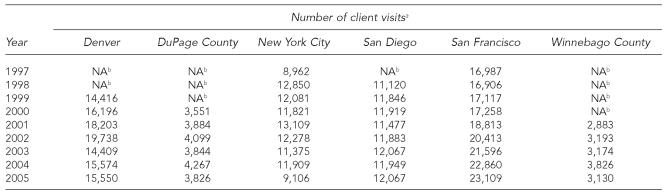

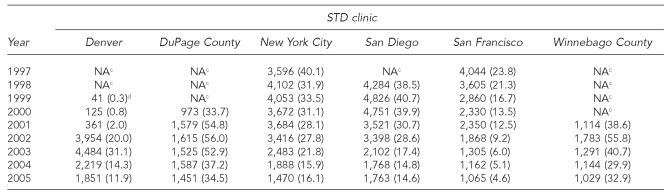

The annual number of client visits to these STD clinics ranged from 2,883 in Winnebago County in 2001 to 23,109 in San Francisco in 2005 (Table 1). The annual number of hepatitis B vaccinations ranged from 125 in the first full year of service in Denver in 2000 to 4,826 in San Diego in 1999 (Table 2). The highest annual hepatitis B vaccination rate was 56 per 100 client visits in DuPage County in 2002; the lowest rate was 0.8 per 100 client visits in Denver in 2000. The median hepatitis B vaccination rate was 28.1 per 100 client visits.

Table 1.

Number of client visits, by STD clinic and year, 1997–2005

Client visits refers to all facility visits, including new clients and multiple visits by some individuals.

Hepatitis B vaccination was not offered by the clinic during this time period.

STD = sexually transmitted disease

NA = not applicable

Table 2.

Total numbera and rate per 100 client visitsb of monovalent hepatitis B and combined hepatitis A and B vaccinations, by STD clinic and year, 1997–2005

Number of hepatitis B vaccinations administered includes number of first, second, and third doses of monovalent or combined vaccine.

Rate is equal to the total number of hepatitis B vaccinations administered divided by the number of client visits multiplied by 100.

Hepatitis B vaccination was not offered by the clinic during this time period.

Start-up year with <six months data

STD = sexually transmitted disease

NA = not applicable

Although the rates of hepatitis B vaccination declined in all clinics in recent years, rates in three clinics—DuPage and Winnebago Counties (2002) and Denver (2003)—increased after a start-up period and then declined. The three clinics (NYC, San Diego, and San Francisco) that began vaccinating clients in the 1980s or 1990s had steady declines in vaccination rates over the study period. The most substantial decline was in San Francisco, where the hepatitis B vaccination rate per 100 client visits decreased by 81% from 23.8 in 1997 to 4.6 in 2005. Hepatitis B vaccination rates declined more gradually and to a lesser extent in NYC and San Diego. In NYC, the rate per 100 client visits decreased 60%, from 40.1 in 1997 to 15.9 in 2004 (16.1 in 2005). San Diego's hepatitis B vaccination rate per 100 client visits decreased 64% between 1999 and 2005, from 40.7 to 14.6.

Staff from the NYC, San Diego, and San Francisco clinics—the three STD clinics that integrated hepatitis B vaccination early on—suggested two explanations for the decreasing vaccination rates. First, after initially offering vaccine to all clients (as recommended by CDC), fiscal concerns or deficits prompted the San Francisco and San Diego clinics to restrict eligibility for hepatitis B vaccination to groups perceived to be at highest risk for infection. Beginning in the late 1990s, the San Francisco clinic prioritized three risk groups for vaccination (i.e., men who have sex with men [MSM], injection drug users [IDUs], and people aged 30 or younger) because of inconsistent vaccine supply as a result of statewide budget problems. Because of fiscal deficits in 2002, San Diego restricted eligibility for hepatitis B vaccination to certain risk groups (e.g., MSM, IDUs), resulting in a 39% reduction in the rate of hepatitis B vaccinations in the following year, from 28.6 to 17.4 per 100 client visits.

In contrast, Denver, which adopted hepatitis B vaccination later, expanded eligibility in 2002 to include all unvaccinated clients, in accordance with CDC's 2002 STD treatment guidelines. This change reportedly improved efficiency because clinicians did not have to screen clients for risk factors. The hepatitis B vaccination rate per 100 client visits increased by 35% from 20.0 (2002) to 31.1 (2003).

Second, staff from the STD clinics that integrated hepatitis B vaccination early on suggested that because their client base was stable, many clients were vaccinated in the early years in which vaccinations were offered; therefore, in later years, fewer clients needed to be vaccinated. For example, in 2003, 81% of San Diego STD clients who had multiple clinic visits had already received at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine.9

In addition, staff from all six STD clinics reported that clients have increasingly reported prior vaccination. By the late 1990s, all of the states represented by participating clinics had laws requiring hepatitis B vaccination for middle school or high school entry.10 Thus, increasing numbers of younger clients may have been previously vaccinated. Evidence from four clinics supports this possible explanation. The rate of clients reporting having already received at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine in the San Diego clinic was almost three times higher among those who attended the STD clinic for the first time in 2003 (29%) compared with those having their first visit in 1998 (11%). From January to June 2006, 55.6% of NYC clinic clients reported prior hepatitis B vaccination or infection. In Illinois, the proportion of clients that reported prior vaccination increased from 13.3% (2000) to 41.7% (2005) in the DuPage clinic and from 27.6% (2001) to 48.8% (2005) in the Winnebago clinic.

Availability of staff licensed to vaccinate clients within the STD clinic itself was cited by the Denver clinic as a major factor contributing to changes in hepatitis B vaccination rates. In September 2002, the Denver clinic used CDC funding to hire a full-time vaccination nurse after a chart review showed that approximately one-third of clients referred to the immunization clinic, which was down the hall from the STD clinic, did not receive the first dose. During 2002, the clinic also expanded eligibility criteria for hepatitis B vaccination. From 2002 to 2003, the rate of hepatitis B vaccination in the STD clinic increased by 54% (from 20.0 to 31.1 doses per 100 client visits), but decreased by 62% in 2004 (to 14.3 doses per 100 client visits) when this position was eliminated. The NYC clinic also found that having staff (i.e., Immunization Public Health Advisors [PHAs]) that could provide vaccinations on-site helped ensure that clients had consistent access to hepatitis B vaccine.

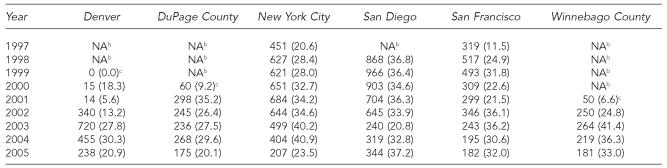

All six STD clinics had hepatitis B vaccination data available by dose number, allowing us to estimate series completion, expressed as the proportion of third to first doses. From 1997 to 2005, the median rate of completion was 30.6% (range, 5.6% to 41.4%) (Table 3). Several STD clinics reported implementing strategies to improve completion rates, such as sending clients reminder letters, fast-tracking clients returning for follow-up doses, reminding providers to screen clients for follow-up vaccination needs, hiring staff to vaccinate clients on-site, and piloting case-management programs with high-risk clients. The latter two interventions were reportedly effective but were discontinued because of cost.

Table 3.

Number and ratea of third doses of monovalent hepatitis B or combined hepatitis A and B vaccinations, by STD clinic and year, 1997–2005

Rate is equal to the number of third doses divided by the number of first doses of monovalent or combined vaccine multiplied by 100.

Hepatitis B vaccination was not offered by the clinic during this time period.

Start-up years not included in assessment of completion of the three-dose series.

STD = sexually transmitted disease

NA = not applicable

DISCUSSION

The findings in this article demonstrate that substantial hepatitis B vaccination in STD clinics is feasible. With commitment of funding, STD clinics administered a median of 28 doses of hepatitis B vaccine per 100 client visits.

Despite this achievement, local or state fiscal shortfalls and loss of CDC funding for viral hepatitis integration in five clinics adversely affected vaccination efforts. Lack of consistent or sufficient funding was a major barrier that contributed to unstable vaccine supply, eligibility restrictions for hepatitis B vaccination, inadequate staffing to administer vaccinations on-site, and inadequate follow-up with clients needing second or third doses. One way that STD clinics attempted to overcome some of the funding-related barriers was through collaborations with state or local entities. The Illinois Department of Health's Immunization Program, for example, contributed almost 50% of the funds used to purchase vaccine;11 and in NYC, immunization PHAs administered hepatitis B vaccinations to reduce the burden on STD clinical staff. (Personal communication, Isaac Weisfuse, Deputy Commissoner, Division of Disease Control, New York City Department of Health, November 2006.)

For three clinics that implemented hepatitis B vaccination from 1999 to 2001 (the two Illinois clinics and Denver), the rate of hepatitis vaccination increased initially and then decreased, but overall the rates declined in all six STD clinics by 2005. There are likely two main reasons for the downward trend: increases in the number of clients reporting prior vaccination, and decreases in funding. Clinics reported that decreased funding led to eligibility restrictions for hepatitis B vaccination and the inability to purchase vaccine or to hire licensed staff to provide vaccinations.

Hepatitis B vaccine is administered as a three-dose series. The median rate of completion in the six STD clinics included in this study was about 30%, similar to rates reported in prior studies.12 Although studies have demonstrated high rates of acceptance of the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine (≥50%), particularly when pre-vaccination counseling was provided, STD clinics were challenged to motivate clients to return for follow-up doses.13–15 However, because the vaccine series does not need to be restarted if the recommended schedule is not followed, clinicians can refer clients for follow-up doses when they return for other services. In addition, providers in a busy clinical setting may not remember or have time to verify whether clients are due for follow-up doses. These findings support a need for additional research to develop multi-tiered interventions (e.g., structural, systems-level, individual-level) to improve hepatitis B vaccination coverage among high-risk adults.16

For STD clinics to implement and sustain comprehensive hepatitis B vaccination programs, designated federal, state, and local funding is needed. Establishing an adult vaccine program modeled on the Vaccine for Children (VCF) program, which provides free vaccines to uninsured or low-income children, would help ensure that high-risk adults are vaccinated against HBV infection.6 Further, vaccinating adults, which accounted for 95% of new HBV infections reported to CDC in 2004,17 might be a cost-effective public health strategy when the costs of treatment and lost productivity are considered.18

Until an adult vaccine program is created, states and urban areas can use federal Section 317 program funds—which can be used to vaccinate anyone with age-appropriate vaccines—to pay for hepatitis B vaccine for high-risk adults seen in STD clinics and other settings. However, states are often faced with the difficult decision to use Section 317 funds to pay for childhood immunizations not covered by the VCF program rather than for adult vaccinations.19

Another option to help ensure that high-risk adults receive hepatitis B vaccination is through private-public partnerships. For example, the Merck Vaccine Patient Assistance Program, which currently provides hepatitis B and other vaccines to income-eligible, uninsured adults seen in the private sector, is being expanded to support some public sector vaccination efforts.19

Another strategy that may help STD clinics increase rates of hepatitis B vaccination is an adult immunization registry similar to existing childhood immunization registries. Electronic childhood immunization registries improve and maintain vaccination coverage by consolidating vaccination records across providers within specific geographic areas and automating reminders for follow-up doses—an otherwise labor-intensive process.20 A similar registry for adults could benefit STD clinic clients, many of whom do not have vaccination records or a regular source of medical care because they are uninsured or underinsured.21, 22

The findings of this study are subject to the following limitations. First, data on the number of clients who reported previous hepatitis B vaccination or infection were limited; therefore, the hepatitis B vaccination rates may be higher than estimated. Second, we were unable to determine whether specific factors were associated with rates of hepatitis B vaccination because these changes tended to overlap. For example, the Denver clinic expanded its eligibility criteria for hepatitis B vaccine around the same time the clinic hired a full-time nurse to vaccinate clients in the STD clinic. Third, annual numbers of client visits include multiple visits by some individuals; thus, we were unable to estimate the proportion of the population that completed the hepatitis B vaccine series. Finally, because this was a convenience sample of STD clinics that received specific funding for or had a long history of providing hepatitis B vaccinations, the findings may not be generalizable to other STD clinics in the United States.

Despite these limitations, this article clearly demonstrates that STD clinics can achieve high volumes of hepatitis B vaccination. Further, the findings suggest that with universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination and recent legislation mandating hepatitis B vaccination for school entry, STD clinics may only need to intensify hepatitis B vaccination efforts for the next 10 to 15 years. However, without adequate funding, especially to purchase vaccine, it is unlikely that the STD treatment recommendation of offering hepatitis B vaccination to all clients will be achieved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention (US) [cited 2006 Sep 15];Viral hepatitis B fact sheet. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/b/fact.htm.

- 2.Goldstein ST, Alter MJ, Williams IT, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K, et al. Incidence and risk factors for acute hepatitis B in the United States, 1982-1998: implications for vaccination programs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:713–9. doi: 10.1086/339192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC (US) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-6):1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC (US) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC (US) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), part II: immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-16):1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthy People 2010. Leading health indicators: immunization. [cited 2006 Sep 21]; Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/html/uih/uih_bw/uih_4.htm#immuniz.

- 7.Handsfield HH. Hepatitis A and B immunization in persons being evaluated for sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 10A):69S–74S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert LK, Bulger J, Scanlon K, Ford K, Bergmire-Sweat D, Weinbaum C. Integrating hepatitis B prevention into sexually transmitted disease services: U.S. sexually transmitted disease program and clinic trends—1997 and 2001. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:346–50. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154503.41684.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunn RA, Lee MA, Murray PJ, Gilchick RA, Margolis HS. Hepatitis B vaccination of men who have sex with men attending an urban STD clinic: impact of an ongoing vaccination program, 1998–2003. Sex Trans Dis. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000258306.20287.a7. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Immunization Action Coalition. [updated 2006 Jul 21; cited 2006 Sep 20];Hepatitis B prevention mandates. Available from: URL: http://www.immunize.org/laws/hepb.htm.

- 11.Zimmerman R, Finley C, Rabins C, McMahon K. Integrating viral hepatitis prevention into STD clinics in Illinois (excluding Chicago), 1999–2005. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):18–23. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC (US) Hepatitis B vaccination among high-risk adolescents and adults—San Diego, California, 1998-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(28):618–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samoff E, Dunn A, VanDevanter N, Blank S, Weisfuse IB. Predictors of acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination in an urban sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:415–20. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000130533.53987.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sansom S, Rudy E, Strine T, Douglas W. Hepatitis A and B vaccination in a sexually transmitted disease clinic for men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:685–8. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000079524.04451.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudy ET, Detels R, Douglas W, Greenland S. Factors affecting hepatitis vaccination refusal at a sexually transmitted disease clinic among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:411–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations to improve targeted vaccination coverage among high-risk adults. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5) Suppl:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC (US) Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(18):509–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SY, Billah K, Lieu TA, Weinstein MC. Cost effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination at HIV counseling and testing sites. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodewald L, Tan LJ. Balancing the childhood immunization program with the urgent needs for adult hepatitis B immunization. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):52–4. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC (US) National Immunization Program. [updated 2005 Aug 30; cited 2006 Sep 21];Immunization information systems. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nip/registry.

- 21.Brackbill RM, Sternberg MR, Fishbein M. Where do people go for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases? Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celum CL, Bolan G, Krone M, Code K, Leone P, Spaulding C, et al. Patients attending STD clinics in an evolving health care environment. Demographics, insurance coverage, preferences for STD services, and STD morbidity. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:599–605. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]