Abstract

Objective

to assess the impact of prolonged displacement on the resilience of Eritrean mothers.

Methods

an adapted SOC scale (short form) was administered. Complementary qualitative data were gathered from study participants' spontaneous reactions to and commentaries on the SOC scale.

Results

Displaced women's SOC scores were significantly less than those of the non-displaced: Mean = 54.84; SD = 6.48 in internally displaced person (IDP) camps, compared to non-displaced urban and rural/pastoralist: Mean = 48. 94, SD = 11.99; t = 3.831, p < .001. Post hoc tests revealed that the main difference is between IDP camp dwellers and urban (non-displaced). Rural but traditionally mobile (pastoralist or transhumant) communities scored more or less the same as the urban non-displaced - i.e., significantly higher than those in IDP camps (p < 0.05). Analysis of variance confirmed that gender is critical: displacement has significantly negative effects on women compared to men: RR = .262, p < .001. SOC scores of urban and pastoralist/transhumant groups were similar, while women in IDP camps were lower scoring - RR = .268, p < .001.

Conclusions

The implications of these findings for health policy are critical. It is incumbent on the international health institutions including the World Health Organization and regional as well as local players to address the plight of internally displaced women, their families and communities in Eritrea and other places of dire conditions such as, for example Darfur in the Sudan.

Introduction

The word ‘resilience’ originates in physics where it is used to describe the plasticity of materials: one that recoils or springs back into shape after pressure has been applied to it is said to be resilient; while a non-resilient material would remain bent, stretched, or simply break under the same pressure. Different materials may have varying degrees of elasticity, and so measuring resilience is an important component of selecting materials for construction - for example for building bridges and houses that can withstand hurricanes and earthquakes. The metaphor of physically resilient objects has been applied in psychology and other behavioral sciences to describe human strength and ability to bounce back, mentally and emotionally, over and above physical recovery from injury and/or exhaustion wrought by crisis events.

Resilience as a concept and topic of research in western psychology may be traced back to the post World War II era. Like the related concepts of ‘hardiness’, ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘locus of control’, resilience came to be associated with individual characteristics and personality traits believed to account for the ability to cope with, and even thrive in adversity. A recent enquiry into psychosocial responses to war determined that the sense of coherence (SOC) and corresponding scale bespeak resilience and can be successfully employed in African settings.1, 2

In conflict and post-conflict situations the displaced face more mental health challenges than their non-displaced counterparts, as clearly demonstrated in the findings of a study carried out by the International Centre for Migration and Health (ICMH) in Bosnia and Herzegovina.3 In their investigation of the health needs of both displaced and non-displaced sections of the populations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Carballo et al. focused on the psychological consequences of loss of place and sense of belonging expressed as sense of powerlessness and lack of control over one's life. However, while the percentage of the study samples reporting feelings of unhappiness and depression “rather more than usual” among the displaced was more than twice that of the non-displaced, the proportions reporting the same feelings “no more than usual” was only slightly higher in the displaced (46%) compared to the non-displaced (44%). More strikingly, only 20% of the displaced reported no feelings of unhappiness and depression compared to 42% of the non-displaced. Clearly, not everyone succumbed to the harmful effects of the war.

Protective factors such as social support may contribute to positive aftermath. It has been argued that humanitarian assistance (a form of social support) can mitigate the worst effects of war and displacement if it is fine-tuned to meet local needs and priorities.4 When external assistance is coordinated and delivered in a timely manner, accompanied by adequate provision of information for those on the receiving end, making sure that they know what is happening and why, the net effect of social support is to preserve and promote existing resilience, at least in the short term. The effect of prolonged displacement on individual and collective resilience had not been examined before. This paper presents primary quantitative and qualitative data from Eritrea where an adapted short form of the Sense of Coherence (SOC) scale was used to measure resilience among both displaced and non-displaced communities.

Study site and historical context

Eritrea became officially independent in 1993 when an UN-supervised referendum formalized its international standing. Prior to that point, the history of Eritrea and its people had been blighted by undue emphasis on the diversity of languages and cultures in the country ever since the British Military Administration (1941–52) tried and failed to divide it up in the hope that “Eritrea will cease to exist”.5 The well documented struggle for territorial integrity and political identity of Eritrea was marked by the resilience of ordinary men and women who built a nation over a total period of 50 years, 30 years of which were spent in the “armed struggle”.6–8 Eritrean women in particular demonstrated remarkable fortitude in supporting and maintaining the struggle for independence against all odds. Women constituted a third of the liberation army not achieved significant social reforms including the right to own land and emancipation in marriage. 9–10 The Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) succeeded in delivering effective primary health care, education and social reform for its largely rural and in the “Liberated Zone” also urban constituents while at the same time responding to Ethiopian military aggression during the protracted war for independence. 11–13

Although Eritrean-Ethiopian relations seemed amicable in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Menghistu regime, unresolved differences between the EPLF and its neighboring TPLF (Tigray People's Liberation Front) were simmering under the surface. Prior to 1991, the EPLF and TPLF were closely allied movements whose common goal was to free the people of Eritrea and Tigray from the tyranny of the Menghistu regime of Ethiopia. Menghistu's fall was instigated by political reforms in the former USSR implemented by Mikhail Gorbachev who made a stop to the seemingly endless supply of arms for the Ethiopian army. As Menghistu fled Ethiopia in May 1991, the EPLF claimed Eritrea and the TPLF (with its ally's EPLF's support) went on to replace the Menghistu government, thus gaining control of the whole of Ethiopia and not just the northern province of Tigray. Moral and financial backing of western governments as well as non-governmental organizations (NGO) continued to favor the Ethiopian government's agenda as articulated by the TPLF-led Ethiopian leadership - in particular by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi whose British (Open University) degree earned him entry into the category of “educated” African leaders. He was reported to have given his tacit approval of Tigrayan militia harassment of Eritrean villagers in the form of random raids and shootings along the border-land leading up to the outbreak of war in 1998. Eritrean response to such incidents was eventually cited the starting as point of the war.14

Over 60,000 internally displaced persons (IDP) lost their homes in Eritrea. Despite international court arbitration and peace agreement signed by both sides in 2002, the actual demarcation of the disputed border is yet to be implemented, and the IDP remain displaced. This state of political stalemate between the two countries has remained unnoticed in the face of more publicized crises in other parts of the world, much to the detriment of ordinary people, especially mothers of young children in the IDP camps in Eritrea. Most notably, the UN Secretary General, Mr Kofi Anan had visited Asmara followed by Addis Ababa in July 2004. A few months later, Ethiopia indicated that it had indeed accepted the court ruling “in principle” while still occupying Eritrean territory in contempt of the court ruling it had signed. This state of affairs remains unchanged as this paper goes to press.

Fieldwork was conducted during June–July of 2003 and 2004. Three internally displaced persons (IDP) camps (Adi Qeshi, Denden, and Hamboka), four urban and/or semi-urban centers (Asmara, Eden/Elaberid, Ghinda, and Gogne), and three rural settlements (Gel'alo, Kelbech, and Shelshela) were included, representing all ethnic/language groups as well as variations in geo-climatic settings and modes of subsistence/livelihood in Eritrea.

Methods

Sense of Coherence (SOC), is a construct defined as: “a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that (1) the stimuli deriving from one's internal and external environments in the course of living are structured and predictable, and explicable; (2) the resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli; and (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement”.15 SOC is thus a “global orientation”, a generalized view of the world as “coherent” or “incoherent”, as the case may be, rather than a specific response to a given stressor. The SOC scale, short form consisting of 13 items was adapted and translated into 9 languages for use in Eritrea.

A total of 265 participants (162 women and 103 men) joined this study upon signing an informed consent form (CF) pre-approved by Tufts University's institutional review body (IRB), and endorsed by the Eritrean Ministry of Health, Primary Health Care division. Both the CF and SOC-13 scale were translated into the nine Eritrean languages, pre-tested, revised, and fine-tuned prior to use. The first author administered the SOC-13 scale with all women participants except those in Asmara who self-administered it in Tigrinya in her presence. The second and third authors administered the SOC-13 scale with men participants. Between them, the first three authors mastered Arabic, Tigre, and Tigrinya as first and/or second languages, and over twenty years of field research experience - a critical requirement for the purposes of this study. In all sites except Asmara, administration of the SOC-13 scale involved reading out each question and allowing the respondent to ask questions and/or comment on the content of the SOC scale - see Box below

Statistical Analysis

The SOC data were analyzed using SPSS and Systat.16 The effect of displacement was examined by comparing SOC scores of women living in IDP camps with the rest, using 2-tailed t-test for equality of means. Following post hoc tests which revealed significant differences within non-displaced participants, the data were grouped into three settlement types: IDP camp; mobile (pastoralist or transhumant); and urban or semi-urban (non-displaced). Analysis of variance was employed to examine the effects of gender and displacement separately, and gender and displacement interaction on SOC scores.

Results

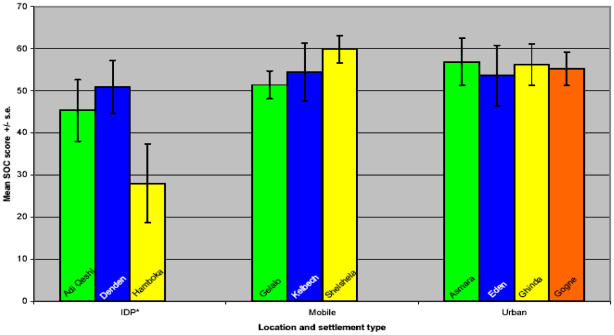

Those living in IDP camps scored significantly less SOC compared to the rest: Mean = 54.84; SD = 6.48 in internally displaced person (IDP) camps, compared to urban and rural settlements: Mean = 48. 94, SD = 11.99; t = 3.831, p < .001. Tukey's Post hoc tests revealed that the main difference was between IDP camp dwellers and urban (non-displaced). Those in rural but traditionally mobile (pastoralist or transhumant) communities scored more or less the same as the urban non-displaced - i.e., significantly higher than those in IDP camps (p < 0.05). Analysis of variance showed that displacement has significantly negative effect on women compared to men: RR = .262, p < .001. Repeating the analysis for the three groups confirmed that urban and pastoralist/transhumant groups are similar, while women in IDP camps are lower scoring - RR = .268, p < .001 - (see Figure).

Figure showing Mean SOC scores by location nested in settlement type (N=157 women)

Participant questions and commentary on the SOC scale revealed that respondents related the scale to both individual orientation to life and collective norms and values. For example, comments on the first question were almost always along these lines:

“How can you ask such a question?”; “I wouldn't be human if I didn't care about what goes on around me, would I?”; “no, this is not in our culture [i.e., not to care about what goes on around oneself], of course I care and try to do something about it, if I can.”; “if I didn't care about what goes on around me, I might as well be dead.”

However, Hidareb (traditionally pastoralist) and some Tigre and Tigrinya women replied to this question differently: they expressed varying levels of interest in what goes on around them; explaining that if they took active interest in everything that goes on around them, they wouldn't be able to attend to their children and other domestic duties. One woman explained, “I choose what to care about from the many things that go on around me.” Other questions provoked responses which reflected collective rather than individual views about the political and socio-economic challenges faced in connection to the recent war and lack of resolution in spite of international arbitration.

Discussion

The most recent national demographic health survey confirms that women bear the brunt of both social and economic burden of post conflict Eritrea.17 A focus on those with young children who continue to face inordinate demands, and the need to examine, recognize and support resilience are thus justified. One of the obstacles to progress in building a credible evidence-base for international humanitarian psychosocial programming has been researchers and practitioner's entrenchment in the medicalised view of trauma and recovery.18, 19

The present study demonstrates the value of combining both qualitative and quantitative lines of enquiry in the study of resilience, the other side of the ‘trauma’ coin. The factors that support and maintain resilience in Eritrean mothers are not unique to Eritreans. It can be expected that other African women (and indeed men) have always relied on and will continue to benefit from traditional systems of social support when facing adversity. What makes the Eritrean experience unique is that contrary to adversary expectations, prolonged hardship and neglect by the ‘international community’ had indeed built collective resilience as the odds were stacked up against Eritrea. The lasting influence of the views of one of the early administrators of “the territory”5 under British Military Administration had proven very hard to correct for six decades.6 While Ethiopian troops remain in occupation of territory confirmed to be Eritrean, the plight of the displaced (on both sides of the border) remains ignored by those with the responsibility to enforce internationally agreed legally binding decisions.

It is clear from the results of statistical analysis above that displacement poses a serious challenge to women who belong to traditionally sedentary subsistence farming communities. Thus the resilience of those in Adi Qeshi, Denden and Hamboka is threatened more compared to those in other locations. Moreover, there are qualitative differences within IDP camp SOC scores: Adi Qeshi residents had benefited from organized evacuation which helped to keep the social fabric intact, while Hamboka residents had suffered a series of relocations driven by public health concerns - the first camp they were sheltered in at Mai Habar had presented the challenges of malaria, although health care facilities were generally adequate. 4 SOC scores in Hamboka were significantly lower than those in other IDP camps indicating harsher conditions endured over prolonged periods of time eroding resilience.

Although in many ways unique and deeply rooted in history and geography, the Eritrean model of humanitarian action that recognizes and supports resilience is transferable and indeed evidently successful in other countries - such as, for example, India after the Tsunami disaster. If international humanitarian agencies genuinely demonstrate “the will and the way” to mitigate disaster, wherever it may strike, there is hope for sustainable alleviation of women's burden in Eritrea and other countries in Africa and elsewhere in similar situations of post war recovery. However, until lessons learnt from failed humanitarian operations translate into profound rethinking of policy and practice with genuine efforts to address non-medical questions appropriately, discrepancy between humanitarian action and rhetoric may continue to hamper progress.20, 21

In conclusion, this study has benefited from the iterative experimental design whereby participants' active engagement in the process of data collection and on-site analysis. The data quality versus quantity trade-offs require careful thought in the ongoing development and fine-tuning of health policy, particularly with respect to the internally displaced.22–24 The findings of this study clearly point to the need for geo-political problems to be recognized and addressed by public health and social welfare institutions locally, regionally and internationally. It would be incumbent for the World Health Organization and partner institutions to advocate for and highlight the plight of long-term displaced populations in Eritrea and elsewhere in Africa, and not turn a blind eye to member states' contempt of international law and justice.

The Sense of Coherence Scale - short form (SOC-13) adapted for use in Eritrea

| 1. | *Do you have the feeling that you don't really care about what goes on around you? | ||||||

| (very seldom or never) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very often) | ||

| 2. | *Has it happened in the past that you were surprised by the behavior of people whom you thought you knew well? | ||||||

| (never happened) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (always happened) | ||

| 3. | *Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you? | ||||||

| (never happened) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (always happened) | ||

| 4. | Until now your life has had: | ||||||

| 5. | (no clear goals or purpose at all) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very clear goals and purpose) | |

| 5. | Do you have the feeling that you are being treated unfairly? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

| 6. | Do you have the feeling that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don't know what to do? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

| 7. | Doing the things you do everyday is: | ||||||

| (a source of deep pleasure and satisfaction) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (a source of pain and boredom) | ||

| 8. | Do you have very mixed-up feelings and ideas? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

| 9. | Does it happen that you have feelings inside you would rather not feel? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

| 10. | *Many people - even those who are strong/resilient - sometimes lose hope in certain situations. How often have you lost hope in the past? | ||||||

| (never) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very often) | ||

| 11. | When something happened, have you generally found that : | ||||||

| (you overestimated or underestimated its importance) | 1 11 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (you saw things in the right proportion) | ||

| 12. | How often do you have the feeling that there's little meaning in the things you do in your daily life? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

| 13. | How often do you have feelings that you're not sure you can keep under control? | ||||||

| (very often) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (very seldom or never) | ||

= reverse score

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for giving generously of their time and knowledge. The Eritrean government Ministry of Education, Curriculum department provided technical assistance in the translation of the consent form and SOC scale into all nine Eritrean languages; our tireless interpreters ensured the smooth running of communications throughout the course of fieldwork. This study was supported by the Henry R. Luce program (Tufts University, USA), the Ministry of Health, Primary Health Care Division (Asmara, Eritrea). Constructive comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers were received gratefully.

References

- 1.Almedom A M. ‘Resilience’, ‘hardiness’, ‘sense of coherence’, and ‘posttraumatic growth’: All paths leading to ‘light at the end of the tunnel’? Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2005;10:253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almedom AM, Tesfamichael B, Mohammed Z, Mascie-Taylor N, Alemu Z. Use of the ‘Sense of Coherence (SOC)’ scale to measure resilience in Eritrea: Interrogating both the data and the scale. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2005 doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001112. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carballo M, Smajkic A, Zeric D, Dzidowska M, Gebre-Medhin J, van Halem J. Mental health and coping in a war situation: The case of Bosnia Herzegovina. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36:463–477. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almedom AM. Factors that mitigate war-induced anxiety and mental distress. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36:445–461. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longrigg S. A Short History of Eritrea. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tesfai Alemseged. Aynfalale 1941–1950. Asmara: Hidri Publishers; 2001. [Tigrinya book] (2002 Reprint) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell D. Against All Odds: A Chronicle of the Eritrean Revolution (with a new Afterword on the Postwar Transition) Lawrenceville and Asmara: Red Sea Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyob R. The Eritrean Struggle for Independence: Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941–1991. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson A. The Challenge Road: Women and the Eritrean Revolution. London: Earthscan; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolde-Sellassie W. The challenging position of Eritrean women: an overview of women's participation in the EPLF. In: Doornbos M, Cliffe L, Ahmed A-G M, Markakis J, editors. Beyond Conflict in the Horn. London: James Currey; 1992. pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabo LE, Kibirige JS. Political Violence and Eritrean Health Care. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;28:677–684. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloos H. Primary health care in Ethiopia under three political systems: Community participation in a war-torn society. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46:505–522. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottesman L. To Fight and Learn: The Praxis and Promise of Literacy in Eritrea's Independence War. Lawrenceville, NJ and Asmara: Red Sea Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tesfai Alemseged. briefing: http:www.dehai.org/conflict/analysis/alemsghed1.html

- 15.Antonovsky A. Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Systat v 10 for Windows.

- 17.National Statistics and Evaluation Office, author. Eritrea Demographic and Health Survey 2002. Claverton, ML: NSEO, Asmara and ORC Macro; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Summerfield D. Effects of war: moral knowledge, revenge, reconciliation, and medicalised concepts of “recovery”. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:1105–1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7372.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summerfield D. A critique of seven assumptions behind psychological trauma programmes in war-affected areas. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:1449–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terry F. Condemned to Repeat? The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaux T. The Selfish Altruist. London and Sterling, VA: Earthscan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolde-Giorgis T. The challenge of reintegrating returnees and ex-combatants. In: Doornbos M, Tesfai A, editors. Post Conflict Eritrea: Prospects for Reconstruction and Development. Lawrenceville and Asmara: Red Sea Press; 1999. pp. 55–100. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health, author. Primary Health Care Policy and Policy Guidelines. Asmara: The State of Eritrea, Ministry of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health, author. National Health Service Guidelines for the Internally Displaced Population (IDP) Asmara: The State of Eritrea, Ministry of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]