Abstract

Objectives

This study was designed to explore the interactions between food securing activities, health and gender equity from the perspective of rural east African women. The specific objectives were to document the critical interaction among these three issues—food security, gender inequity, women's health within the context of sub-Saharan Africa; to describe the nature of this triad from the perspective of women farmers in Africa; and to propose a framework for linking available interventions to the vicious nature of this triad.

Setting

In-depth interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with rural women farmers in Kwale District, Kenya and Bagamoyo District, Tanzania.

Methods

A total of 12 in-depth interviews and 4 focus group discussions have been included in this analysis. Transcribed text from interviews and focus group discussions were coded and thematic conceptual matrices were developed to compare dimensions of common themes across interviews and settings. A thematic analysis was then performed and a framework developed to understand the nature of the triad and explore the potential for interventions within the interactions.

Findings

The vicious cycle of increasing work, lack of time, and lack of independent decision making for women who are responsible for food production and health of their families, has health and social consequences. Food securing activities have negative health consequences for women, which are further augmented by issues of gender inequity.

Conclusion

The African development community must respond by thinking of creative solutions and appropriate interventions for the empowerment of women farmers in the region to ensure their health.

Keywords: Food security, Gender equity, Women's health, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Worldwide, and in Africa in particular, women traditionally play a critical role in securing food for their families. Despite major constraints women are expected to meet the basic survival needs of the continent1. Among poor women of the world, rural women farmers of Africa have one of the lowest social status and they are often expected to support themselves and their families virtually independently. In Africa, while men cultivate cash crops, women's agricultural work is primarily in subsistence crops. Women farmers are disadvantaged and constrained in many ways. They own only 1% of the land, receive less than 7% of farm extension services, receive less than 10% of the credit given to small-scale farmers and are undernourished, illiterate and lack a voice in the decisions affecting their lives2,3. The informal participation of women in agriculture demonstrates the extent of “invisible” work they do as major contributors towards food security and the impact it has on their own nutritional status and health of their families1,4.

From having access to land to grow food, to cooking and eating the food, there is a broad range of food securing and related activities that impact women's nutritional and health status5. Food securing activities include working as laborers on the land, as well as a myriad of processing activities such as clod breaking, seed sorting and treatment, transplanting, weeding, harvesting and storing. There are household food preparation activities that include fetching water, gathering wood, grinding grains into flour, and drying and pounding cassava. Additional responsibilities for women include the transportation and marketing of some of what they and their husbands may grow as cash crops3. Other household responsibilities include washing, breast-feeding, and various aspects of caring for children and family members. These activities and the time they consume make competing demands on women within a context of poverty and powerlessness which has important implications for their well-being6.

The overall purpose of this exploratory study was to explore the linkages between food securing activities, health, and gender inequity from the perspective of rural East African women farmers. The specific objectives were to document the critical interaction between these three issues — food security, gender inequity, women's health — within the context of sub-Saharan Africa; to describe the nature of this triad from the perspective of women in East Africa; and to propose a framework to link interventions with the vicious nature of this triad. Although the literature is rich in consideration of two of these three factors, to our knowledge there has been little specific work to explore the perspectives of women food farmers in East Africa regarding this triad of issues.

Methods

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University collaborated with co-investigators from the Aga Khan Health Services and the University of Nairobi, Kenya to conduct 7 in-depth interviews and 2 focus group discussions with women in Kwale District, Kenya. In Tanzania we collaborated with scientists from Muhimbili Medical Center in Dar es Salaam to conduct 5 in-depth interviews and 2 focus group discussions with women from Bagamoyo District. The women were purposively sampled in each site, and the criteria for selection of focus group participants included self-identification as a farmer and primary residence in the chosen villages. The empirical data from this exploratory study is intended to provide an understanding of women's perceptions on food security, health and gender inequity in the sub-Saharan African setting.

The interviews and focus groups were semi-structured and field guides were developed to help discussion around broad themes. Investigators from Kenya and Tanzania were encouraged to probe for additional relevant information that emerged during the interviews and discussions. A participatory method to measure time burdens was used where women were given a fixed number of beans and asked to allocate them on a grid of various tasks7. All interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in the local language and tape recorded. Tapes were translated into English and transcribed for data entry and analysis. Transcribed text was manually coded and thematic conceptual matrices were developed based on coding of data to compare dimensions of common issues. A thematic analysis was then performed and a framework developed to understand the nature of the triad and explore the potential for interventions within the interactions.

Results

Four research questions are used as a framework to organize the presentation of results: 1) How do gender inequities affect women's food securing activities? 2) How do gender inequities affect the health of women and their families? 3) What is the relationship between food securing activities and health from women's perspective? 4) How are some women able to manage demands that are placed on them by food securing activities and maintain a healthy household in the context of these gender inequities? Finally, we end with a description of linkages of these results to potential intervention strategies.

How do gender inequities affect women's food securing activities?

It is clear from the interviews in Tanzania and Kenya that women are primarily responsible for planting, growing and harvesting the food to sustain their families, as well as for managing other household tasks such as food preparation which includes fetching water and firewood, hygiene, and health care for children. Women's work begins early in the morning and usually lasts until late in the evening, with few opportunities for rest during the day. As mentioned by a woman in Tanzania, “The agricultural activities are so time consuming that you hardly have time to rest. The cassava farm might need your attention but at the same time the paddy farm also needs your attention. The only thing you can think about is farm work.” Or as stated by a woman in Kenya, “At 6am I fetch water. By 7am I am sweeping and cleaning dishes. I then proceed to the farm. I then look for food to be cooked at lunchtime. I go back to the shamba (farm) until 6pm. Then I cook supper. I spend from 7 until 12, and 2 until 6 on the farm every day.”

Men's contributions to household responsibilities vary. In some households men seem to contribute substantially to farming activities including preparing fields for planting, weeding, and harvesting. In other households, the male heads of household have paid employment outside of the home, and as a result most of their time is spent fulfilling these responsibilities. There were also examples of households where the men were not employed outside of the household, but they also did not contribute substantially to farming activities. As stated by a woman in Tanzania, “Many men in our village do not participate in agricultural activities. It is the women who do most of the farm work. They [men] spend most of their time at the market place playing cards. When you [woman] come back from the farm, it is expected that you go to fetch water. From the farm you have to come back with a load of firewood. If there are no vegetables and you have a nearby garden then you will have to take care of it. All this time your husband does not know if you are back or what is going on. And to make matters worse, he might even be angry with you for delaying food. If there is no food in the house then you will have to wait for him to come back, or if you have some money, you can buy flour and prepare food for the family.”

In all households, whether men contributed or not to the farming and domestic activities, women were primarily responsible for farming the food that sustained their families. Some women referred to tightly controlled social norms around division of labor in the household. There were certain domestic tasks such as collecting firewood and preparing food that men were prohibited from assisting with in the household. It was suggested that peer pressure may play a part in that men would be embarrassed or ashamed to be found participating in these activities. This is what a Kenyan woman said, “[Whose work is it to look for water?] The women. In only very few families you can see a man fetching water…[Who fetches firewood?] The women. They believe that man is not allowed to collect firewood, even he cannot carry the firewood from outside of the house to the kitchen.” Or another woman saying, “[Who fetches firewood?] Mothers and daughters. [Is there some time when fathers assist in fetching firewood?] Sometimes he gives money to buy those ready (bundles of firewood for sale) but it is not easy for him to fetch firewood for domestic use.”

In Tanzania, women were asked to rank the amount of time that they spend on each activity, by placing beans on the grid of various farm and household activities that they perform. They were then asked to do the same for men (husband/partner) and a clear pattern emerged (Table 1). Overall, food preparation was ranked the highest in terms of time consumption for women, followed by activities such as farming, cleaning, and fetching water. Resting and business were lower in the rank (Table 1A). On the other hand, women indicated that men spent the most time resting, followed by business activities, and then farming (Table 1B)8. In addition to the rank order, the total number of activities also varied by gender.

Table 1A.

Time spent by women on daily activities, Tanzania

| Activity | Ranking (# beans) |

| Food preparation | 259 |

| Farming | 218 |

| Cleaning | 162 |

| Fetching water | 87 |

| Fetching firewood | 58 |

| Resting | 43 |

| Gathering food | 36 |

| Business related activities | 32 |

# The greater the number of beans, the greater the time spent

Table 1B.

Ranking of men's daily activities by women in Tanzania

| Activity | Ranking (# beans) |

| Resting | 384 |

| Business | 291 |

| farming | 103 |

| Fishing | 83 |

While the role of men in food securing activities tends to be minimal in comparison to women, their role in decision-making about what food should be produced, what food should be consumed, and what food should be sold was substantial. Women clearly do the majority of the work related to food security, yet their capacity to make independent decisions about such issues is limited. Most women indicated that they had little authority to make decisions about food production, consumption or sale, independently of their husband. As a Tanzanian woman describes, “Although I do the cultivation on my own, I can not decide to sell anything from the farm on my own. I will have to tell my husband first unless it is an emergency. For instance, if my child is sick and my husband is not home, I can take two sacks of maize and sell them so that I can take my child to the hospital. When my husband returns I can report to him….my husband decides if we should sell the crops. He has to be aware of everything that goes on in the family.”

In Tanzania, most of the women interviewed, indicated that at the level of the village, women do participate in decision-making on issues that concern the community. In some villages, women were elected members of the village committees: “Yes, women participate in these discussions. We have a councilor for women on the village committee. She is the one responsible for allocation of loans.”

Other women said that although women participate, their views are often not taken seriously: “You might be elected to be a member of one of the village committees but you are of no use. They do not involve you in anything they do. In the village leadership hierarchy you have both men and women but when it comes to issues like selling village property, instead of involving both men and women, it is only the men who make the decisions.” From interviews with Kenyan women, the role of women in village-level decision making seemed to be less pronounced. When asked what role women may play in these decisions one woman said, “It is not common for women to talk, although men do listen to their opinion, he does not value it very much. The sole decision-makers are men.” Another woman stated that:“[Who makes decisions related to the community? The elders, such as fathers and others. [How do women contribute to these decisions?] They normally agree with these decisions. [Why?] Because the elders have said so. ”

How do gender inequities affect the health of women and their families?

Women were asked about intra-household food distribution. While there were no clear food restrictions for women, and very poorly defined restrictions on what pregnant women eat, the actual eating patterns in the household do reflect inequities between men and women. In several cases when asked who gets served first within the household the women said that first she serves her husband and then she eats later with the rest of the children. A woman farmer in Tanzania said, “My husband eats first, then the children and I follow”, while another described the process as “We serve the food first for my husband and my sons. My daughters and I eat together. I serve food for all of them.” A Kenyan woman said, “My father is fed first and then children and women last.” This pattern reflects both a process within households but also differential amounts or quality of food served to men. It has been noted from other locations that not only do men eat first but they are often served the highest quality food products9,10,11. This unequal pattern of food distribution between genders within the household from childhood through adulthood may have long-term nutritional and health implications for women and female children.

Women are primarily responsible for the health care for their children. This responsibility does not necessarily translate into an ability to make decisions independently about health care needs for children. Rather, it means that women are responsible for monitoring the health care of their children, and when there is a child in need of treatment, they are responsible for raising the problem with their husband or another household member such as a mother-in-law before taking action to seek treatment for the child. As described in Tanzania, “If a child is sick you first have to discuss it with your husband before you take any steps. Even if you have separated with the father you have to inform the father that the child is sick”.

When husbands are away because of employment or for other reasons, then women do make the decision to treat the child on their own in Tanzania: “I can decide on my own to take the child to the hospital because sometimes my husband is at work and I cannot wait for him to come home. I will take my child to the hospital and if he decides to beat me he will have to do it at the hospital.” Interviews from Kenya also indicated that women often have space to make independent decisions in cases of emergencies, especially related to children's health, without fear of harmful repercussions. There was little information on the consequences of women's independent actions in other spheres of life. However, the quote above does suggest that negative consequences, including physical violence, may be a risk for women who make decisions without consulting with their husband/partner.

What is the relationship between food securing activities and health from women's perspective?

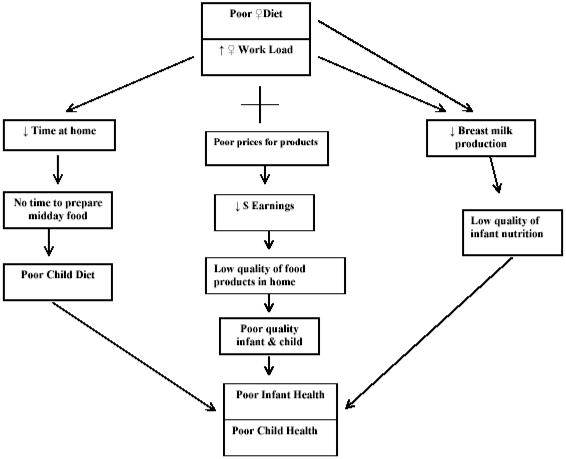

There were a few informants who made a direct linkage between food securing activities and health (Figure 1). A participant made the link between poor nutritional status of women, heavy workloads and reduced breast milk production: “We women in the village eat a very poor diet, and as a result if one is breastfeeding the milk is not enough. That is why we are forced to feed our babies ugali (a stiff maize meal porridge) at such an early age. Otherwise, the child would cry all the time because he/she is hungry.” In another example, a woman made the link between the heavy demands of cultivation and the lack of time for food preparation, “Children do not normally eat lunch because the mother spends the whole day in the farm. So when you are back from the farm, you have to make sure you work very fast so at least by 7pm food is ready for the family. Our children suffer when we have to cultivate far from the home because there is nobody to cook for them. If they have an elder sister then they are lucky.”

Figure 1.

Potential health consequences of food securing activities by women

The low prices that women are paid for their products also impact the resources that the family has to spend on food consumption and health. “It is only out of difficulties that we do this (collect and sell firewood), but the price at which we sell a bundle of firewood, does not match the hardship of the work. You can sell a bundle of firewood at a price as low as Tsh. 500 [local currency] since you need the money. Coming back you also have to walk. Boarding a bus from Bagamoyo means paying Tsh. 200 so you will only be left with Tsh. 300.” Women would be left with a positive balance of 300 Tsh ($ 0.25USD) from the sale of a bundle of firewood after paying the bus fare they would need to return from Bagamoyo to their village. This is a profit that the woman above notes is not worth the physical effort and time it takes to gather the wood. Collecting a bundle of firewood takes between 30 minutes and 2 hours depending on the distance women live from the forests. If women were to avoid paying the bus fare and walk to Bagamoyo the return trip would take approximately four hours.

How are some women able to manage food securing activities and maintain a healthy household in the context of gender inequities?

There were some examples of women who were able to generate and manage income independently of their husbands, or to participate equally in household decision-making. A number of factors were mentioned that may contribute to women's ability to make independent decisions including: 1) independent ownership of land, 2) independent generation of income (through women's groups or business), 3) types of decisions (i.e. production of non-permanent crops on farm land), 4) no children as a result of the relationship, and 5) specific emergencies (i.e. health emergency for child).

In one case, the woman stated that she and her husband each had their own farm for which they were each responsible. “We each have our own different farms so each of us can decide on his/her own, to do what we want with the food that we harvest. [So your husband does not have any say over what you decide to do with the food that you harvest?] No, he doesn't. I can do anything I want with it.” One focus group participant stated, “In our case, most of our husbands do not participate in agricultural activities. You are the mother of the family. If you sit around and wait for your husband to decide it means your children will starve.”

In another very interesting interview a woman was married for the second time. In this second marriage the couple had not given birth to any children together. In this case the woman felt more responsible to her children from a previous marriage than she did to her current husband. As the woman stated: “[How do you decide in your family if you want to buy a new farm?] I can involve my children and I can also involve my husband. But since we have no children together, he cannot object to my views. He has another family and I also have my children who will help me in the future. So I have to take their advice into consideration, even if my husband does not agree with what I am planning to do…by being the mother of his child it would have been possible for him to overrule whatever decisions I have made.”

95% of women interviewed, said that they belonged to a women's group, although the focus and organization of these groups varied. Several of the groups produced and sold products such as mats, baskets, bread, and fried fish. One group operated a water kiosk in which they sold buckets of water to village members, while other groups planted and harvested food from a common plot of land. There were a couple of groups that developed a revolving loan fund amongst its members. Most women said that they did benefit from participation in these groups. The groups benefited both the individual women and their families by providing benefits such as income or free farm products for home consumption. Women also personally benefited through the generation of independent income that allowed them to spend a small amount on their own needs. Women in Tanzania said, “I have benefited by being a member of the group. I have managed to get a small amount of money with which I bought some clothes”; and “The garden belongs to the group and I must say that we have been lucky because we don't pay for the water we use. We started by paying 500 Tsh and now we have 18,000 Tsh”; and “After harvesting we sell our products and divide the profit among ourselves. We also save some money in the bank. When I get money from the group I buy clothes. The rest I am saving because I want to start a business.”

Discussion

The triad of issues explored in this paper may be an object of study for researchers but it is a reality for women in African countries. The lack of food security, compounded by gender inequity, has critical implications for the health of women and their families. Studying only two of these three factors ignores the critical interactions from the third. Through this paper, we are proposing a new proactive paradigm that evaluates the triad and assess the impact of interventions on all three factors. This holistic paradigm challenges the health community working on each individual issue to extend their horizon to realize the impact of their work on the other two areas.

This study was meant to provide an initial insight into the interactions of the triad of issues- food insecurity, gender inequity, ill health — that plague the lives of women in Africa. The collection of primary qualitative data from women farmers in rural Tanzania and Kenya has provided a remarkable indigenous knowledge base for such an exploration. The interviews and focus group discussions are limited in scale and are certainly not meant to be generalized to other populations within or outside sub-Saharan Africa. However, such studies contribute to our understanding of these critical human issues, and the themes echoed in the interviews reinforce the commonalities among women's experiences in the region1,12,13.

One of the most revealing insights of this work has been the realization that women in these societies are trapped by a vicious cycle of work and more work for every day of their lives. The “work” they do is not only that which they need to do for themselves or their children, but that defined by “society” — meaning male members who define social norms. Men decide on what should be done by women, when, and at what times. Work occupies most of a woman's day as a result of which she has no time for herself. This lack of time leads to an inability to participate in decision making activities, resulting in a woman not being able to take or affect decisions and consequently not being able to change the life she is leading. Additional impediments to this cycle which deserve further investigation include burdens placed on female headed households, and the effects of illnesses such as HIV on a woman's ability to cope with farm work. In some instances, the added burden of child care keeps elder girl children from school, hampering their education and increasing gender inequities. The self-perpetuating cycle of work needs to be the target of future socio-cultural interventions.

The women farmers of Africa were able to clearly explain the nature, pace and intensity of their food securing activities; they recognize the physical and time burden it places on them; and they also recognize interactions between these activities and health of themselves and their children (fig 1). The burden of securing food for their families is a time consuming task, and also causes physical and mental stresses on the women and their children. The inability to control, market and reap the rewards of their labor makes their efforts more frustrating. At the same time, such effects are not equally distributed across all women, and there are instances of successful women farmers who have decision-making capacity within their households. However, this study tends to reflect that such cases entail specific characteristics within the woman such as ownership of land.

One of the objectives of this study was to explore linkages between the triad of issues and potentially available interventions. How can women break the cycle of having less food, being powerless and being physically unhealthy? The insights gathered from Tanzanian and Kenyan women farmers provide us with a wealth of ideas regarding current approaches to help women manage their food securing activities and maintain a healthy household in the context of substantial gender inequities. In Kenya, the construction of a dam with funding from the Aga Khan Foundation substantially reduced the amount of time that women had to spend fetching water each day. Another intervention that helps women reduce the time required for basic tasks is the mechanization of agriculture. In one focus group discussion several women mentioned that they were disadvantaged because they relied on hand held hoes for tilling. By providing women with the means to mechanize their labor, the amount of time that women have to spend on farming activities is reduced, or alternatively women can cultivate more land in the same amount of time.

Access to credit schemes is yet another intervention which improves the opportunities for women to sustain group activities and generate extra income for household use. This finding is important for both researchers and development professionals in propagating the type and functions of women's groups. In addition, women spend an enormous amount of time in transit between their home and farms, sources of water, forests, and markets. In both Tanzania and Kenya much of the transit time is spent on foot because local motorized transportation is not reliable, available or affordable. Strategies to improve time management for women are therefore linked with issues of local transportation. This requires the road and transport sector to value the benefits of transportation for women and respond to their needs.

The interviews suggest that women bear the largest burden in terms of both ensuring that their children are fed adequately each day, and monitoring the health of their children. However, in many households women lack the authority to make decisions about food production and health care. There is a basic disconnect here, in that women are responsible for the health of the family but they cannot make independent decisions. Potentially, men need to take more responsibility for the nutrition and health of their families, while women need to be empowered and given more authority to make critical decisions in caring for their families.

The exploratory research conducted in two countries has limitations, and did not delve into a number of other issues within the triad of food security, gender inequity and women's health. The conclusions reached here may provide guidance to researchers and practitioners in east Africa, but cannot be extrapolated to the entire continent. The study was also limited by not having available data on the religious background and education level of the women, or the health status of their families with respect to HIV, and consequently, sub-analyses could not be performed. The study did not explore the role of pregnancy and its effect on agricultural work, although the literature suggests that the duration of women's agricultural work is not compromised14. Finally, there was a minority of women who were able to make decisions regarding food security independently of the men, but it is not known if this ability relates to their educational, religious or cultural status.

Conclusion

It is important to recognize the links to available intervention strategies, while acknowledging that other long term strategies are also needed to address the underlying issues perpetuating this triad. This formative work supports the notion of longer term social change and although it is a difficult and slow process, it is critical if meaningful changes are to be sustained within the triad of food insecurity, gender inequity and women's burden of ill-health. There is a fundamental need to promote a more balanced division of labor within the household. It is abundantly clear from this study and from other bodies of research in sub-Saharan Africa, that women are overburdened with food securing activities12,15. They are primarily responsible for all food production, food preparation, food storage and food sale within the family. The help that they receive from the male members of their family is episodic and limited to specific tasks such as felling trees, building fences and digging fields. Providing girls with equal access to education and training is another long-term strategy that will be important to sustain changes in the status of women. There is evidence that even a slight increase in women's education does have a meaningful impact on the health of children16,17,18. Finally, working with men to develop an ethic of responsibility for the health of their families is long term goal for health and development efforts in Africa.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the valuable support of the Muhimbili University in Tanzania; the Aga Khan Health Services, and the University of Nairobi in Kenya; and Kim Ashburn and Nirali Shah at Johns Hopkins. This project was made possible by a grant from The Center for a Livable Future, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA.

References

- 1.Howson CP, Harrison PF, Hotra D, Law M, editors. In her lifetime: female morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Medicine; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Hunger Project, author. Her Future is Africa's Future. New York: The Hunger Project; 1999. The African Woman Food Farmer. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food & Agricultural Organization, United Nations, author. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Rome: FAO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNDP, author. Human Development Report 1995. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laier JK, Davies S, Milward K, Kennan J. Gender, household, food security and coping strategies. Sussex, UK: Institute of Development Studies; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quisumbing AR, Brown LR, Feldstein HS, Haddad L, Pena C. Women: key to food security. Washington, DC: Food Policy Statement. International Food Policy Research Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development. 1994;22(7):953–969. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berio AJ. The analysis of time allocation and activity patterns in nutrition and rural development planning. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 1980;6:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gittelsohn J, Thapa M, Landman LT. Cultural Factors, Caloric Intake and Micronutrient Sufficiency in rural Nepali Households. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44(11):1739–1749. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gittelsohn J. Opening the Box: Intrahousehold Food Allocation in rural Nepal. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;33(10):1141–1154. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90230-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdulla M, Wheeler EF. Seasonal variations and the intrahousehold distribution of food in a Bangladeshi village. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;41(6):1305–1313. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.6.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lado C. Female labour participation in agricultural production and the implications for nutrition and health in rural Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34(7):789–807. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson A. Women's health in a marginal area of Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 1986;23(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prentice AM, Spaaij CJK, Goldberg GR, Poppitt SD, van Raaij JMA, Totton M, et al. Energy requirements of pregnant and lactating women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;50(suppl):82–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gittinger JP, Chernick S, Horenstein NR, Saito K. World Bank Discussion Papers. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 1990. Household food security and the role of women. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleland J, Gineken JK. Maternal Education and Child Survival in Developing Countries: The Search for Pathways of Influence. Social Science and Medicine. 1988;27(12) doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pena R, Wall S, Persson L. The Effect of Poverty, Social Inequity, and Maternal Education on Infant Mortality in Nicaragua, 1988–1993. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(1):64–69. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoham-Yakubovich I, Barell V. Maternal Education as a Modifier of the Association between Low Birthweight and Infant Mortality. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;17(2):370–377. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]