Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) diseases is often made on clinical grounds alone in Nigeria due to lack of endoscopic facilities. The validity of using such diagnosis is presently unknown.

Objective

The study aimed to determine: age and sex distribution of patients presenting for UGI endoscopy; pattern of clinical and endoscopic diagnoses in patients with UGI diseases; and, the validity of clinic-based diagnosis.

Methods

Medical records of patients presenting at Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria for UGI endoscopy between September 1999 and August 2003 were reviewed. Data was analysed for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of clinical diagnosis using endoscopic diagnosis as “gold” standard.

Results

Males constituted 53.4% of subjects and mean age was 45 years (± 1.69 SD). Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) constituted 67.6% of referral diagnosis but 33.9% of endoscopic diagnosis. PUD had the highest sensitivity value (0.72) while gastritis had the least (0.04). Specificity ranged from 0.40 for PUD to 1.00 for corrosive oesophagitis. Positive predictive value ranged from 0.29 (oesophageal cancer) to 0.67 (corrosive oesophagitis) and negative predictive value ranged from 0.66 for gastritis to 0.99 for corrosive oesophagitis.

Conclusion

The validity of clinical diagnosis in UGI conditions varied widely, and in general, there is poor agreement between clinical and endoscopic diagnoses.

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) diseases are leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)1, gastroesophageal reflux2 disease and cancers3 are leading UGI conditions and affect millions of people worldwide. Endoscopy holds an important place in the diagnosis and treatment of UGI conditions4,5. It enables visualization, photography, ultrasonography, and biopsies of suspicious lesions. Upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy (UGIE) also facilitates the performance of therapeutic procedures such as UGI tract sclerotherpy, polypectomy, and gastrostomy.

In Nigeria and many developing countries facilities for UGIE are rare. As a result, the diagnosis of UGI conditions is carried out solely on clinical parameters in most cases. The degree of success in the treatment of such diagnosed cases would naturally depend on extent to which the clinical diagnoses are correct, although “placebo effect”6 could also be responsible for some positive outcomes. Incorrect diagnoses, and subsequent ineffective management, may result in increased morbidity period, economic loss to the client, and even death.

To what extent are clinic-based diagnoses in UGI diseases, in the absence of UGIE, likely to be correct? What conditions are more likely to be accurately diagnosed and which ones would likely be missed without the benefit of UGIE? These questions are of practical importance to health care practice in resource-constrained environments, but they have been largely left unresearched. Considering the fact that facilities for UGIE may not become widely available in many African countries in the immediate future, the research questions addressed in this study are critical to improving health care practices. The study had three specific objectives: the first was to describe the age and sex distribution of patients presenting for UGIE; secondly, to determine the pattern of clinical conditions in patients undergoing UGIE based on clinical features (referral diagnosis) and endoscopic evaluation; and, thirdly, to determine the validity of clinic-based diagnosis.

Patients and methods

Study Location

The study was conducted in Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife (OAUTHC), Nigeria. The hospital is a pioneer center for UGIE practice in West Africa. The entry points for UGIE procedure in OAUTHC consist of medical and surgical gastroenterology units of the hospital and direct referrals from other health facilities. UGI patients are referred to OAUTHC from various parts of Nigeria, particularly the six states in the south-west geo-political zone.

Study Population and Data Collection

All patients (882) that underwent UGIE between September 1999 and August 2003 at OAUTHC constituted the study population. The medical record of each patient was reviewed and information pertinent to the objectives of the study, including referral diagnosis and endoscopic findings, were extracted using a standardized format.

Endoscopic evaluation of patients was carried out using fibre optic gastro-duodenoscope Olympus (GIF - 2T10 & Q30) and following standard procedures. Instrument sterilization was done using a routine technique of cleaning the instrument with cetrimide, 70% alcohol, gluteraldehyde (Cidex®) and later running equipment in distilled water for 20 to 30 minutes in-between endoscopic sessions. Endoscopic examinations were undertaken with a pre-medication which included use of intravenous buscopan (hyoscine) 40mg, diazepam 2–5mg or midazolam 1–5mg to achieve sedation and gut relaxation. Patients with suspected liver disease or renal compromise did not have any sedation. To facilitate easier passage of the endoscope tube 10% xylocaine® spray was used for local throat/oropharyngeal anesthesia. During examination, patients were usually placed in the left lateral decubitus with pulse oximetry monitoring. All anatomic regions of the oesophagus, stomach, first and second parts of the duodenum were examined and endoscopic impressions noted. Mucosal biopsies for histopathological diagnoses and Helicobacter pylori detection were obtained for all cases of oesophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and suspected malignant lesions (the results of these constitute the focus of another study). Most of the patients had UGIE as an elective procedure and informed consents were duly obtained. The endoscopy team during the period of study consisted of general surgeons and gastroenterologists, with one of the pioneers of endoscopic services in West Africa (AOA) as the head of the team. Diagnoses conform to standards as reflected in publications such as the atlas of gastrointestinal endoscopy7.

Data Entry and Analysis

Data entry and analysis were carried out through the use of SPSS 11.5. Univariate analysis was carried out to determine the sex and age distributions of the patients as well as the pattern of diagnosis of referral and UGIE diagnoses. Chi-square (X2) analysis was used to compare the age-group distribution of relevant disease entities.

Criterion-referenced validity involves the comparison of findings obtained through a particular method/process to that obtained using a reference standard or method (termed “the gold standard”). In the context of this study, UGIE constituted the gold standard. Cross-tabulation of diagnosis from referral facilities (based on essentially history and physical examination, and hereinafter referred to as “clinical diagnosis”) and the endoscopic diagnosis was undertaken and depicted in a 2 x 2 table for the analysis of criterion-referenced validity. Based on the cross tabulation, the degree to which the clinical diagnosis agreed with the endoscopic diagnosis was determined for different disease entities where both diagnoses exist in the patient's medical record. Standard epidemiological indices for assessing validity of measures - sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive values - were determined for the clinical diagnosis (in comparison with the reference standard) 6,8,9.

Sensitivity refers to the ability of a test procedure to correctly identify individuals who have a specific disease (as determined by the gold standard), while specificity refers to the ability of the test procedure to correctly identify non-diseased individuals. Applied in the context of this study, sensitivity was calculated as the proportion of respondents identified as having a specific condition by endoscopy that were similarly diagnosed on clinical ground. Specificity was calculated as the proportion of those identified through endoscopy as not having a specific condition that clinical diagnosis also did not label as having the condition. On the other hand, the positive predictive value refers to the proportion of individuals positive to a test procedure who were actually having the disease according to the gold standard while negative predictive value is the analogous measure for those who were identified by the test procedure as not having the condition in question. The positive predictive value was calculated in this study as the proportion of those diagnosed on clinical basis as having a particular disease and who were confirmed by endoscopy as having the said condition. Negative predictive value was calculated as the proportion of those who were reckoned on clinical ground as being free from a disease (i.e. not diagnosed as having the disease) who were similarly classified on the basis of endoscopic findings. The measures of validity were calculated separately for different disease entities.

Results

A total of 882 patients underwent UGIE during the four-year period covered in the study (September 1999 to August 2003). The patients consisted of 471 (53.4%) males and 411 (46.6%) females, and the mean age was 45 years (± standard deviation of 1.69) (Table 1). While patients' age ranged from infancy to old age, those in the fifth decade of life constituted the largest cohort (22.3%), followed by those in the third and fourth decades of life (17.9% and 17.8% respectively).

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients that presented for upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy at OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: 1993 to 2003

| Age | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1-9 years | 2 | 0.2 |

| 10-19 years | 30 | 3.4 |

| 20-29 years | 158 | 17.9 |

| 30-39 years | 157 | 17.8 |

| 40-49 years | 197 | 22.3 |

| 50-59 years | 139 | 15.8 |

| 60-69 years | 126 | 14.3 |

| 70 years and above | 73 | 8.3 |

| Total | 882 | 100.0 |

As Table 2 shows, peptic ulcer disease constituted two-thirds (67.6%) of the referral diagnosis, distantly followed by gastric cancer (7.0%) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (6.9%). Carcinoma constituted less than a tenth of the diagnosis made clinically (carcinoma of the stomach 7.0%; oesophargeal carcinoma 0.8%). The endoscopic diagnoses are presented in Table 3, with many patients having multiple diagnoses. Fifty-eight (6.0%) patients were found to be normal at endoscopy. A third (33.9 %) of the patients had conditions classifiable as peptic ulcer disease - gastric ulcer (9.1%) and duodenal ulcer (24.8%). Thus, the ratio of duodenal ulcer to gastric ulcer in the endoscopic finding was 5:2. About a quarter of the patients had oesophageal disorders, with reflux oesophagitis as the most common findings (20.1%) followed by oesophageal varices (3.2%). In the stomach, the main findings were acute gastritis (35.0%), followed by gastric erosion (13.9%), and acute-on-chronic gastritis (12.7%). Acute duodenitis (with or without gastritis) was the most common duodenal endoscopic findings (31.3%), followed by duodenal ulcer (24.8%) and duodenal erosion (9.1%). Cases of carcinoma was recorded in 12.6% of patients: 5.8% early gastric cancer; 5.8% advanced gastric cancer; and, 1% Oesophageal cancer.

Table 2.

Pattern of referral diagnosis among patients with upper gastro-intestinal conditions referred to OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: 1999–2003

| Referral Diagnosis | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 596 | 67.6 |

| Cancer of the stomach | 62 | 7.0 |

| Upper gastro-intestinal bleeding | 61 | 6.9 |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | 50 | 5.7 |

| Reflux oesophagitis | 23 | 2.6 |

| Gastritis | 21 | 2.4 |

| Oesophageal cancer | 7 | .8 |

| Duodenal perforation | 3 | .3 |

| Corrosive | ||

| oesophagitis | 3 | .3 |

| Others | 56 | 6.3 |

| Total | 882 | 100.0 |

Table 3.

Pattern of upper gastro-intestinal endoscopic findings among patients in OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: 1999–2003

| Endoscopic findings | Frequency | Percentage |

| Acute gastritis | 309 | 35.0 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 219 | 24.8 |

| Reflux oesophagitis | 177 | 20.1 |

| Acute duodenitis | 142 | 16.1 |

| Acute gastroduodenitis | 134 | 15.2 |

| Gastric erosion | 98 | 13.9 |

| Gastric ulcer | 80 | 9.1 |

| Duodenal erosion | 74 | 8.4 |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | 61 | 6.9 |

| No abnormality | 58 | 6.0 |

| Gastric cancer (advanced) | 51 | 5.8 |

| Early gastric cancer | 51 | 5.8 |

| Others | 115 | 13.0 |

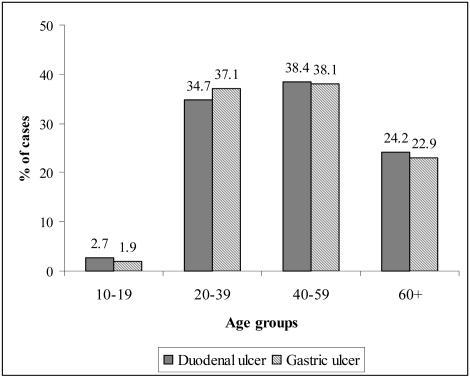

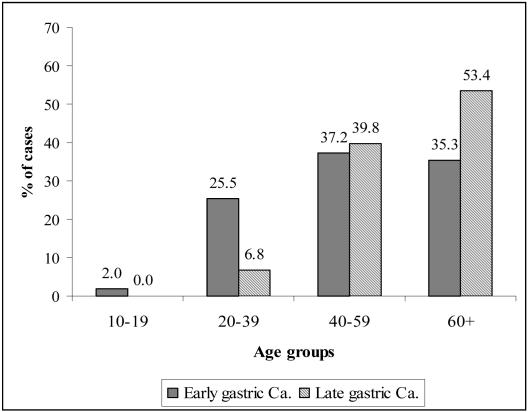

In terms of age distribution of cases, the pattern for duodenal and gastric ulcer were generally similar, with the highest proportion of cases occurring between the ages of 40 and 59 years (38.4% of duodenal ulcer and 38.1% of gastric ulcer cases) (Figure 1). Statistical analysis (X2) did not show any significant difference in the pattern of age distribution of duodenal and gastric ulcers (p=0.950). A higher proportion of cases of advanced gastric cancer occurred patients who were 60 years of age and above (53.4%) compared to early gastric cancer cases (35.3%) (Figure 2); the age distribution differed significantly, statistically, between the two types of gastric cancer cases (p<0.011). While almost all cases of early gastric cancer (94.1%) occurred before 70 years of age, more than a third of late cancer cases (34.5%) occurred above the age of 70 years. The peak of the early gastric cancer cases was in the 7th decade of life (29.4%) compared to the 8th decade in late gastric cancer cases (24.1%).

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of age of patients endoscopically-diagnosed with duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer in OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: 1999–2003

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of age of patients endoscopically-diagnosed with early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer in OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: 1999 – 2003

Among the non-cancerous conditions diagnosed at referral facilities on clinical ground, peptic ulcer disease had the highest sensitivity level (0.72), but the specificity was quite low (0.40). Corrosive oesophagitis, which had the highest level of specificity (1.00), had only a sensitivity of 0.29 while gastritis had sensitivity of 0.04 and specificity of 0.98 (Table 4). Cancer of the stomach had sensitivity of 0.35 and specificity of 0.97, while oesophageal cancer had sensitivity of 0.20 and specificity of 0.99.

Table 4.

Relationship between referral and definitive diagnosis in upper GI conditions

| Disease Condition | Clinical (Referral) | Definitive diagnosis (Endoscopic findings) diagnosis | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative Predictive value | |

| Disease | Disease | ||||||

| present | absent | ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Peptic ulcer | Present | 214 (24.3%) | 382 (43.3%) | ||||

| disease | Absent | 85 (9.6%) | 201 (22.8%) | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.70 |

| Gastric outlet | Present | 24 (2.7%) | 26 (3.0%) | ||||

| obstruction | Absent | 37 (4.2%) | 795 (90.1%) | 0.39 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 0.96 |

| Gastritis | Present | 12 (1.4%) | 9 (1.0%) | ||||

| Absent | 297 (33.7%) | 564 (63.9%) | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.66 | |

| Reflux | Present | 10 (1.1%) | 13 (1.5%) | ||||

| oesophagitis | Absent | 162 (18.4%) | 697 (79.0%) | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.81 |

| Corrosive | Present | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | ||||

| oesophagitis | Absent | 5 (0.6%) | 874 (99.1%) | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.99 |

| Cancer of the | Present | 36 (4.1%) | 26 (2.9%) | ||||

| stomach | Absent | 66 (7.5%) | 754(85.5%) | 0.35 | 0.97 | 0.58 | 0.92 |

| Oesophageal | Present | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.6%) | ||||

| cancer | Absent | 7 (0.8%) | 868 (98.4%) | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 0.99 |

Discussion

This study was based on 882 patients who presented for UGIE over a 4-year period in Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria - a leading medical center for endoscopy in Nigeria and West Africa. Based on the clinical epidemiological approach of criterion-referenced validity, we sought to determine the usefulness and limitations of clinical approach (only) in the diagnosis of various upper gastro-intestinal conditions by comparing clinic-based diagnosis with endoscopy. Criterion-referenced validity has been described as “the best and most obvious way of appraising validity”6.

Our findings with regard to peptic ulcer disease as the most common UGI condition and the difference in the age distribution of early and late gastric cancers are in line with current knowledge1,5,10. The finding that 58 patients (6.0%) were endoscopically normal compares favourably with previously reported results from endoscopic evaluation of UGI patients11,12: these persons may have been suffering from functional dyspepsia or non-ulcer dyspepsia11,12.

The prevalence of gastric carcinoma recorded in our endoscopy cases (11.6%) was higher than that recorded in some previous studies, but when considered with the occurrence of other solid tumours in West Africa13, the prevalence rate is comparatively low. Furthermore, our findings in the cases of gastric cancers showed a higher proportion of cases in early stages (50.0%), where radical “curative” surgery could be effective, compared to those in the late stages in contrast to previously reported works from Nigeria where most cases of gastric were diagnosed at late stages14,15,16. The difference can be directly attributable to the use of endoscopic procedure that facilitated early detection in our cases unlike other studies that reported basically on clinical manifestations and diagnosis.

A comparison of the pattern of referral and UGIE diagnosis showed a wide difference in the prevalence attributed to many conditions. In the case of PUD, for example, the rate of referral diagnosis (67.6%) was twice that of endoscopic diagnosis (35.0%). On the other hand, whereas gastric cancer constituted 7.0% of diagnosis on clinical ground, it constituted 11.6% of UGIE findings. This pattern indicates poor concurrence between clinical (referral) and endoscopic diagnoses. The generally low level of sensitivity and positive predictive value obtained in the study also highlights the poor association between clinical and UGIE diagnoses. This may possibly be a reflection of combination of two factors: the clinical acumen of the individual medical practitioner and the limitations inherent in the application of clinic-based judgment as the sole basis of diagnosis in UGI conditions. Several limitations of clinic-based diagnosis were obvious from our findings. Firstly, clinical (referral) diagnoses are generally non-specific in nature. This is not unexpected as it may be clinically difficult to distinguish precisely between several conditions, for example, between acute gastric ulcer, gastritis, gastroduodenitis, or even ulcerated gastric cancers. In comparison, UGIE-based diagnosis provided far richer clinical information, with potential for guiding more precise and prompt treatment. Secondly, the potential of clinic-based diagnosis to identify some conditions, such as gastric cancer, in their early and “treatable” stages is very poor. Thirdly, diagnosis made on clinical ground may simply be inaccurate in many cases as reflected by the various validity indices used in the study.

The findings from our study have implications for health care situation in Nigeria and other resource-constrained environment: the poor association between clinical diagnosis and endoscopy findings strongly highlights the need to improve health infrastructure if improved health care service delivery and health outcomes are to be achieved. This study provides an evidence-based platform for health advocacy in this regard. The use of endoscopy for UGI conditions, by increasing the accuracy of diagnosis, would facilitate prompt and accurate treatment as well as reduce morbidity period and mortality. It is important to also note that availability of UGIE would result in cost-effectiveness in case management as the incidence of failed treatment resulting from “empirical” non-evidence based approach would be reduced.

References

- 1.Graham DY, Rakel RE, Fendrick AM, Go MF, Marshall BJ, Peura D P, Scherger JS. Scope and consequences of peptic ulcer disease: How important is asymptomatic Helicobacter pylori infection? Postgraduate Medicine. 1999;105:106–119. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.03.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bello IS, Arogundade FA, Sanusi AA, Adesunkanmi AR, Ndububa DA. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a review of clinical features, investigations and recent trends in management. Nigerian Journal of Medicine. 2004;13:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendricks D, Parker MI. Oesophageal cancer in Africa. IUBMB Life. 2002;53:263–268. doi: 10.1080/15216540212643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axon ATR, Bell GD, Jones RH, Quine MA, McCloy RF. Guidelines on appropriate indications for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:853–856. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6983.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tytgat GNJ. Role of endoscopy and biopsy in the work up of dyspepsia. Gut. 2000;50(Suppl. 4):13–16. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.suppl_4.iv13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson JH, Abramson ZH. Survey methods in community medicine. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. Validity; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiller KFR, Cockel R, Hunt RH, Warrant BR. Atlas of gastrointestinal endoscopy and related pathology. London: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2002. pp. 19–226. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lequesne M, Wilheim F. Methodology for the clinician. Compendium and glossary. Basel: Eular Publishers; 1989. Rating indexes: sensitivity, specificity and predictive value or reading the signs: Nostradamus in the 20th century; pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Last JM, editor. A dictionary of epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York, N Y: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ndububa DA, Agbakwuru AE, Adebayo RA, Olasode BJ, Olaomi OO, Adeosun OA, Arigbabu AO. Upper gastrointestinal findings and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia. West African Journal of Medicine. 2001;20:140–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey RF, Salih S Y, Read AE. Organic and functional disorders in 2000 gastroenterology outpatients. Lancet. 1983:632–634. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shennak MM, Tarawneh MS, Al-Sheikh TM. Upper gastrointestinal disease in symptomatic Jordanians. A prospective endoscopic study. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1997;17:471–474. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1997.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badoe EA, Archampong EQ, da Rocha-Afodu JT. Principles and practice of surgery including pathology in the tropics. Ghana Publishing Corporation; 2000. pp. 570–602. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajao QG. Gastric carcinoma in a tropical African population. East Africa Medical Journal. 1982;59:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arigbabu AO. Gastric cancer in Nigeria. Tropical Doctor. 1988;18:13–15. doi: 10.1177/004947558801800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correa P P, Haenszel W. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. In: Correa P, Haenszel W, editors. Epidemiology of cancer of the digestive tract. Vol. 2. Hague: Mattinus-Niijhoff; 1998. pp. 58–84. [Google Scholar]