Abstract

Low copy repeats (LCRs; segmental duplications) constitute ∼5% of the sequenced human genome. Nonallelic homologous recombination events between LCRs during meiosis can lead to chromosomal rearrangements responsible for many genomic disorders. The 22q11.2 region is susceptible to recurrent and nonrecurrent deletions, duplications as well as translocations that are mediated by LCRs termed LCR22s. One particular DNA structural element, a palindromic AT-rich repeat (PATRR) present within LCR22-3a, is responsible for translocations. Similar AT-rich repeats are present within the two largest LCR22s, LCR22-2 and LCR22-4. We provide direct sequence evidence that the AT-rich repeats have altered LCR22 organization during primate evolution. The AT-rich repeats are surrounded by a subtype of human satellite I (HSAT I), and an AluSc element, forming a 2.4-kb tripartite structure. Besides 22q11.2, FISH and PCR mapping localized the tripartite repeat within heterochromatic, unsequenced regions of the genome, including the pericentromeric regions of the acrocentric chromosomes and the heterochromatic portion of Yq12 in humans. The repeat is also present on autosomes but not on chromosome Y in other hominoid species, suggesting that it has duplicated on Yq12 after speciation of humans from its common ancestor. This demonstrates that AT-rich repeats have shaped or altered the structure of the genome during evolution.

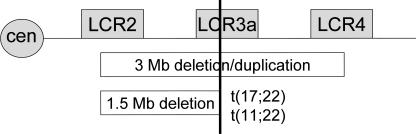

The human 22q11.2 region is susceptible to chromosome rearrangements leading to multiple congenital malformation disorders (for review, see McDermid and Morrow 2002). The most well recognized is velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome, 22q11DS; MIM 192430; MIM 601,362) associated with a recurrent 3-Mb hemizygous deletion (Morrow et al. 1995; Carlson et al. 1997; Shaikh et al. 2000). A newly described developmental disorder occurs in individuals with a duplication of the same region that is deleted (Edelmann et al. 1999; Ensenauer et al. 2003). The deletion and duplication result from nonallelic homologous recombination events between two 240-kb low copy repeats (LCRs) termed LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (Fig. 1; Babcock et al. 2003). Approximately 7% of 22q11DS patients have a nested distal deletion endpoint in a third LCR22, LCR22-3a, lying equidistant between LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (Fig. 1). In addition to deletions and duplications, translocations also occur in 22q11.2, some within LCR22s. The constitutional t(11;22) translocation is the most common non-Robertsonian recurrent translocation in humans and the breakpoint on 22q11.2 is in LCR22-3a (Fraccaro et al. 1980; Zackai and Emanuel 1980; Funke et al. 1999). Another, more rare recurrent translocation, the t(17;22) translocation occurs in the same region as well (Kehrer-Sawatzki et al. 1997; Edelmann et al. 2001). In addition, other de novo translocations also occur on 22q11.2, several in the vicinity of LCR22s (Spiteri et al. 2003). The chromosome breakpoints on 22q11.2 for the recurrent translocations are in the center of an AT-rich palindrome, hypothesized to form unstable cruciform structures (Kehrer-Sawatzki et al. 1997; Kurahashi et al. 2000; Edelmann et al. 2001). Analysis of the AT-rich palindromes mediating 22q11.2 translocations revealed that the frequency of the translocation is higher when the AT-rich palindrome is nearly perfect or symmetrical, underscoring the importance in the structure of these elements in chromosome rearrangements (Inagaki et al. 2005; Kato et al. 2006).

Figure 1.

LCR22s mediate deletions/duplications and translocations. The line spanning left to right, represents the q11 region of chromosome 22 (cen indicates centromere). The LCR22s mediate the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome), the reciprocal duplication syndrome, as well as the known recurrent t(11;22) translocation and t(17;22) translocation. LCR22-2 and -4 are >99% identical and through homologous recombination mediate the deletion syndromes, as well as, the duplication disorders. LCR22-3a is involved in the deletion syndromes as well but is predominately involved in translocations.

The eight LCR22s are composed of genes and partial pseudogene copies forming a complex mosaic, comprising 11% of the 22q11.2 region (Bailey et al. 2002; Babcock et al. 2003). Since the LCR22s are responsible for several human genomic disorders, efforts have been initiated to determine how their complex structure has formed during evolution. As a first step, we examined the DNA sequence of the full-length genes present in the LCR22s, specifically, USP18, BCR, GGTLA1, and GGT1 and compared them with the sequence at the endpoints of the partial pseudogene copies. We found that Alu SINE (short interspersed repetitive element) elements were present at the borders of the pseudogene copies. This implicated Alu elements in mediating recombination events, thereby shaping the architecture of the LCR22s (Babcock et al. 2003). This was found to be consistent with a whole-genome analysis of the LCR endpoints (Bailey et al. 2003). The Alu recombination events do not explain all the rearrangements because they are not all the endpoints of chromosome breakage within the LCR22s.

AT-rich repeats are present within clusters in the LCR22s associated with human genomic disorders, LCR22-2, -3a, and -4. They are part of a tripartite 2.4-kb repeat containing two other elements: a subclass of human satellite I DNA (566 bp; HSAT I) and an AluSc SINE. Examination of these LCR sequences revealed that chromosome breakpoints occurred within the AT-rich repeat, thereby shaping or altering LCR22 architecture during evolution. To determine if the tripartite repeat mapped to other genomic regions that could be susceptible to chromosome rearrangements, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mapping studies. In addition to chromosome 22q11.2, the tripartite repeat was found in the pericentromeric regions of the acrocentric chromosomes by PCR analysis and examination of the reference human genome sequence. It was also found on the Yq12 as determined by FISH mapping. The HSAT I sequence is absent on chromosome Y in primate species but present in autosomes, suggesting that these are recent additions on chromosome Y. Thus, the AT-rich repeats, responsible for translocations disrupting the 22q11.2 region, are in regions of the genome that have become rearranged during primate evolution. Our findings further illustrate the dynamic nature of the structure of the human genome.

Results

AT-rich repeats shape LCR22 structure

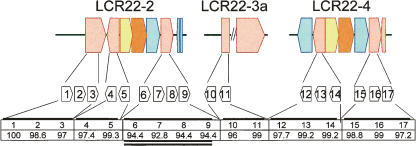

Examination of the sequence of LCR22-2 and LCR22-4, associated with chromosome rearrangement disorders, revealed a series of AT-rich blocks present within some of them (Fig. 2; Babcock et al. 2003). To determine the number of copies and the sequence context of the AT-rich repeat in the LCR22s, we examined its organization in the annotated human genome sequence (March 2006 assembly; UCSC Browser) (Kent et al. 2002). The AT-rich sequence is present within a tripartite repeat consisting of a subfamily of the human satellite I element, termed HSAT I, and an AluSc. The HSAT I has a complex organization. It is composed of two parts, a simple classical satellite consisting of an A-B-A-B-A array where A is 17 bp and B is 25 bp, and a complex repetitive sequence termed DYZ2, which has been considered the male specific HSAT I (Frommer et al. 1982, 1984; Prosser et al. 1986). There were varying numbers of the tripartite repeat clusters within the LCR22s (Fig. 2, USP18 block, pink; Babcock et al. 2003). BLAT analysis was performed to determine the percentage of identity among them. All the copies of HSAT I were compared to the most centromeric HSAT I element, and therefore, it is the percentage of identity to this template that is shown in Figure 2. The HSAT I elements were between 93.8% and 99.2% identical to each other. The percentage of identity was similar between each AluSc element located immediately adjacent to each HSAT I element (data not shown). HSAT I’s in the largest cluster of repeats (repeats 6–9) showed the greatest divergence with the other HSAT I copies and with each other (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. 1). This suggests that the individual HSAT I elements within this cluster of four HSAT I elements may have been the oldest; although based upon the high level of homology, all have evolved recently during primate evolution.

Figure 2.

Organization of HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich sequence in the LCR22s. The LCR22s are made of blocks or modules shown here in the block structures (LCR22-2 is 241,823 bp; LCR22-3 size is not determined; LCR22-4 is 245,258 bp; Babcock et al. 2003). The different colors represent the different gene portions the LCR contains and its organization: USP18, pink; BCR, blue; GGT2 (found in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4, while GGT1 is found in LCR22-8) and GGTLA1, yellow; IGSF3 (pseudogene; real gene found on chromosome 1p13.1), orange. The blocks found under the LCR blocks represent the known HSAT I elements. These HSAT I elements are found in both orientations and are associated with Alus and AT-rich sequence. The orientation is centromere to telomere of 22q11.2 from left to right. The numbers represent the percent identity between the HSAT I’s, using the most centromeric element as reference.

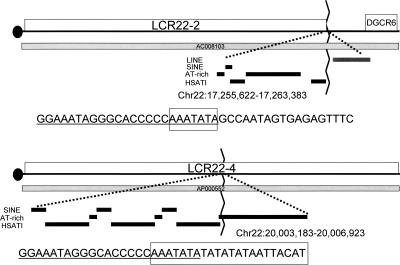

Examination of the tripartite repeat and the endpoints of the LCR22s revealed a breakpoint between LCR22-2 and adjacent non-LCR22 sequences within the AT-rich repeat (Fig. 3). This region is the distal end of LCR22-2, upstream of the DGCR6 gene. These data suggest that the AT-rich repeat might have mediated gross LCR22 duplications during evolution. The same region was present within LCR22-4, but not at its end. Based upon these findings, we can hypothesize that LCR22-4 served as the progenitor. The centromeric breakpoint is not shown in the figure, as it doesn’t contain the repeat. Likely, the duplication was created by double crossover via nonhomologous recombination.

Figure 3.

Breakpoint at end of LCR22-2 is in AT-rich sequence. The image above shows the distal end of LCR22–2 (boxed) on chromosome 22q11.2 present in the genomic clone, AC008103. The DGCR6 gene is adjacent to the LCR22. The repetitive element track, showing LINEs, SINEs, AT-rich repeats, and HSAT I elements, adapted from the UCSC Browser genome assembly (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) is shown. The precise end of LCR22-2 is located within an AT-rich repeat. The sequences at the breakpoint are shown, with the unique sequence to the right of the AT-rich repeat. The position of the breakpoint is boxed. The chromosomal region containing LCR22-4 is shown below the respective region of LCR22-2. The genomic clone, AP000552 spans the interval. Similarly, the repetitive sequences are shown below the clone, with the position of the breakpoint, as boxed. Data are consistent with a breakpoint in the AT-rich repeat, within LCR22-4, resulting in the formation of LCR22-2.

To determine if this tripartite repeat was present elsewhere in the genome, BLAT and BLAST analyses were performed. As expected, this repeat was found in the three LCR22s, and in addition, one copy of the element was found on the pericentromeric chromosome 21p11.1 region, in an island of overlapping genomic clones, containing at one end, centromeric α-satellite repeats.

HSAT I elements are present on acrocentric chromosomes

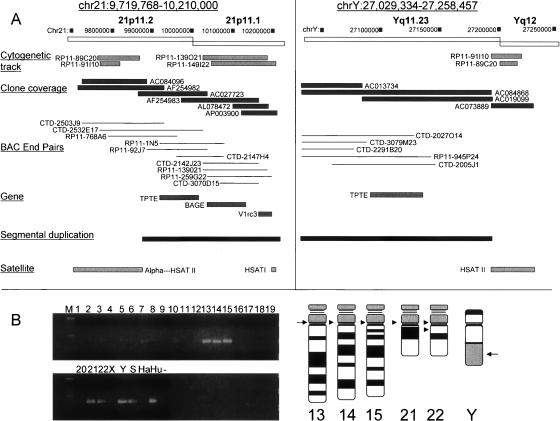

The annotated sequence from a 490,232-bp contig on chromosome 21p11.1 containing the only other mapped tripartite repeat in the reference genome sequence, was examined more closely to delineate annotated sequence features (Fig. 4A, left). Examination of the FISH mapping track (cytogenetic track) in the UCSC Browser (March 2006 assembly) revealed that two BACs (RP11-91I10, RP11-89C20) that are located near the tripartite repeat, hybridized to the pericentromeric regions, p11.1–p11.2, of all the acrocentric chromosomes. The two BACs contained predominantly human HSAT II sequences, consisting largely of (GAATG)n. The HSAT II repeat is present in the same sequenced BAC clones (AC084096, AF245982) as α-satellite sequences. α-satellites comprise human centromeres, thereby forming a direct physical linkage between the contig in Figure 4A (left) and centromeric regions, in this case, of acrocentric chromosomes.

Figure 4.

HSAT I/AT-rich repeat is found on the acrocentric chromosomes and Y. (A, left) A chromosome 21p11 pericentromeric island of overlapping clones contains the tripartite repeat element (listed as HSAT I in the satellite track). The genomic clones used for physical (Clone coverage track) and FISH mapping (Cytogenetic track) are indicated below the boxes representing the acrocentric pericentromeric interval on chromosome 21p11.2 and 21p11.1 as adapted from the UCSC Browser, March 2006 assembly. Three genes were identified as shown, with their exon-intron structure (Gene track). The segmental duplication tract was incorporated into the diagram, with satellite type shown. There are three classes of satellites in this region, α-satellites, present at the very 5′ end of the chromosome 21p11.1 region; HSAT II [(GAATG)n]; and HSAT I satellites. (Right) The chromosome Yq11.23–12 junction contains similar features as the 21p11 region. There is striking similarity between the clones mapping to 21p11 and the Yq11.23-q12 interval. The Yq11.23-q12 junction is shown depicting the genomic clones used for physical and FISH mapping as adapted from the UCSC Browser. The 3′ ends of BAC clones AC019099, AC084868, and AC073889 contain HSAT II simple satellite sequence. The contigs are connected to the Yq12 interval based upon FISH mapping with clones RP11-91I10 and RP11-89C20. Additional validation as to the presence of HSAT II is shown in Figure 7. The TPTE gene maps to the 21p11 and Yq11.23 regions as shown. The tripartite repeat is missing from the reference human sequence for this interval and it is now shown in A. (B) The HSAT I element maps to the acrocentric chromosomes. PCR was performed using DNA template from the hamster-human somatic cell hybrid panel (Coriell repositories) using HSAT I F/R primers. The first lane represents a 100-bp ladder, each number represents the individual human chromosome, including X and Y. Ha is hamster DNA, Hu is human DNA, S is GM06317 (chromosome Y hamster–human somatic cell hybrid), and − is the negative control. The PCR product from different chromosomes were 400 bp in size. The acrocentric chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, 22, and Y were amplified. An idiogram of the acrocentric chromosomes and chromosome Y, with arrows in the putative position where the HSAT I elements are present, is shown.

The annotated sequence of the island of genomic clones in the 21p11.1 region was examined to search for genes. There are three genes/pseudogenes present, TPTE, BAGE3, and a homolog of a mouse gene, V1rc3 (Fig. 4A, left). These genes comprise a segmental duplication and are present in the acrocentric chromosomes, among other regions, confirmed by FISH mapping (RP11-139O21, RP11-149I22) (Fig. 4A, left; Chen et al. 1999; Ruault et al. 2003). The genomic clones shown in the map from the UCSC Browser were linked by significant depth (clone coverage and BAC end pairs) and thus suggest that the tripartite repeat maps to the centromeric regions of acrocentric chromosomes, regions that as of yet are unmapped (Fig. 4B, right, arrows).

To validate the presence of the HSAT I element on the acrocentric chromosomes, we performed PCR analysis using primers specific to the portion of the HSAT I element that was conserved among primate species on DNA from a hamster–human somatic hybrid panel (Fig. 4B). A PCR product was detected in the lanes containing the acrocentric chromosomes (Fig. 4B).

To gain insight into the relative percentage of sequence divergence and thus evolutionary history of the HSAT I sequence in the different acrocentric chromosomes, we sequenced the PCR products obtained from the chromosome panel (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. 1). The 400-bp HSAT I PCR products from different chromosomes were 96%–99% identical with each other. We realize that there may be multiple copies of this element on each individual chromosome; thus, the sequence obtained may be representative of each chromosome. This suggests that they have formed recently during evolution or that gene conversion has served to homogenize the sequences. To validate precisely where the HSAT I elements mapped on the acrocentric chromosomes, we performed low- and high-stringency FISH mapping with a 400-bp HSAT I probe and separately with the 2.4-kb tripartite repeat probe, but we could not detect a signal, likely due to the small number of copies of the repeat in the acrocentric chromosomes.

HSAT I elements are similar in size

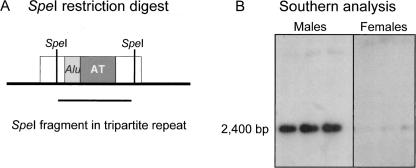

The AT-rich sequence within the tripartite element varied in length on genomic clones that have been sequenced (largely from chromosome 22q11.2). This could be due to actual differences in size in the human genome or artifactual differences in annotated sequence from genomic clones. To determine whether the HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich repeat showed variability in size in the unmapped regions of the genome, we performed a genomic Southern blot hybridization experiment using the restriction endonuclease, SpeI, which digests once per tripartite repeat (Fig. 5A). A faintly detectable 2.4-kb DNA SpeI fragment was present in female human genomic DNA (three unrelated females) (Fig. 5B), and a strongly detectable, similar sized fragment was present in male DNA (Fig. 5B). This suggests that there is one predominant repeat length and that perhaps the AT-rich sequence is rearranged in BAC clones. There were more copies (∼20-fold) of this element in male DNA than female DNA, consistent with previous reports that it is amplified on chromosome Y (Cooke et al. 1982). To verify the sequence composition, we resequenced seven independent copies of the tripartite repeat, including the AT-rich repeat.

Figure 5.

Genomic Southern blot hybridization shows a specific hybridization in males as compared to females. (A) SpeI restriction digestion of genomic DNA. SpeI cuts once per tripartite repeat (HSAT I, open box; AluSc, light gray box; AT-rich sequence, dark gray box). The line below the genomic interval depicts the 2.4 kb fragment. (B) Genomic DNA was isolated from human blood lymphocytes and digested with SpeI, separated on 0.8% agarose gel and hybridized with a α-32P-dCTP–labeled HSAT I probe. The HSAT I probe detects the 2.4 kb tripartite repeat, which is present in greater copy number in male DNA as compared to female DNA.

AT-rich repeats are on Yq12

We noted that another copy of the TPTE gene, mapping to the segmental duplication in the acrocentric chromosomes was found at the most telomeric part of the Yq11.23 region, juxtaposed to the unmapped Yq12 band (Fig. 4A, right). Of interest, the BACs, RP11-91I10 and RP11-89C20, containing HSAT II sequences found in acrocentric chromosomes, mapped to this region as well. PCR analysis of somatic hybrid cell lines containing chromosome Y, indicated that the HSAT I mapped to chromosome Y (Fig. 4B). There were no HSATI/Alu/AT-rich repeats detected in the currently available, human genome assembly (UCSC Browser, March 2006 [build 36.1]) of Yq12, since it is heterochromatic and thus unmapped. Based upon the similarities of the map of 21p11.1-cen and Yq11.23-q12, we hypothesize that the tripartite repeat must lie in the vicinity of the Yq11.23-q12 region, in the unmapped portion. Consistent with this hypothesis, previous publications described HSAT I elements as being present in the heterochromatic region(s) on chromosome Y (DYZ2 component, or known as the male HSAT) (Gosden et al. 1975a, 1977; Prosser et al. 1981). Their precise structure or map position has remained elusive. For example, there are some differences in the literature regarding other chromosomal locations of HSAT I (Gosden et al. 1975b, 1977; Prosser et al. 1981). The Y HSAT I sequence was 97.97% identical to those on the acrocentric chromosomes.

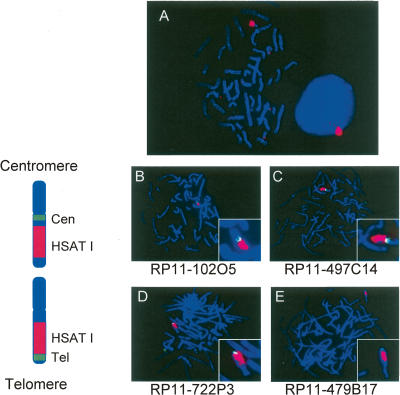

To determine the map position of the HSAT I repeat on chromosome Y, we performed FISH mapping on male metaphase chromosomes from lymphocytes. The tripartite repeat probe (data not shown) as well as the HSAT I specific repeat probe (400-bp PCR product) painted the unmapped, heterochromatic long arm of chromosome Y, the Yq12 band (Fig. 6). The FISH data using HSAT I probe confirms the presence of HSAT I on chromosome Y, but not necessarily of the tripartite repeat. The evidence for the presence of this repeat on chromosome Y is provided from the performed Southern and PCR/sequence analysis of subclones from chromosome Y. The tripartite repeat thus maps to Yq12. In fact, many copies are present. Based upon the similarities between the contig on 21p11.1-cen and the contig on Yq11.23-12, illustrated in Figure 4A, it can be hypothesized that the tripartite repeat could have originated in one of these two regions, became transposed onto the other region, and, once seeded, was able to duplicate and expand in copy number.

Figure 6.

Painting of chromosome Yq12. (A) FISH mapping on DAPI-stained metaphase and interphase human male peripheral blood lymphocytes with the 400-bp cloned PCR product of HSAT I, shown here in red. A signal was detected on chromosome Y. In the interphase cell, the hybridization of the HSAT I probe occurs near the periphery of the nucleus. We had two-dimensional images. Thus, we could not be sure of the position in all the nuclei. We saw the peripheral location in >60%–70% of 100 nuclei examined in separate experiments. (B) Positioning of HSAT I on chromosome Y. FISH mapping on DAPI-stained metaphase human male peripheral lymphocytes showing the position of HSAT I on the Y chromosome. (B,C) The BACs RP11-102O5 and RP11-497C14 (green) map more centromeric on chromosome Y than HSAT I (red). (D,E) The BACs RP11-722P3 and RP11-479B17 (green) map more telomeric on chromosome Y than the HSAT I probe. On the left of the FISH mapping pictures are the ideograms orientating the probes on the chromosome. HSAT I is localized on chromosome Y in the q12 band.

Usually heterochromatic or nontranscribed regions lie near the nuclear periphery of interphase cells (Scheuermann et al. 2004). As expected, the Yq12 region that contains that HSAT I repeat was located at the periphery of the nucleus in 60%–70% of interphase cells (Fig. 6A), perhaps providing some structural or functional significance.

It has been known that the long arm of chromosome Y contains satellite sequences. However, their organization has remained elusive (McKay et al. 1978; Schmidtke and Schmid 1980; Schmid et al. 1990; Ludena et al. 1993). To accurately define the location of HSAT I on chromosome Y, FISH mapping was performed on human male lymphocytes using BAC probes with precisely known locations on chromosome Y (UCSC Browser, May 2004 [build 35]) and the 400-bp HSAT I probe (Fig. 6B–E). Two BACs, RP11-102O5 and RP11-497C14, mapping to Yq11.23, which were used to generate probes for FISH mapping, were located centromeric to HSAT I on chromosome Y (Fig. 6B,C). In contrast, two BACs, RP11-722P3 and RP11-479B17, mapping to the telomeric end of chromosome Y, were distal to HSAT I on chromosome Y (Fig. 6D,E), indicating that HSAT I is precisely located in the unmapped region Yq12. Due to the high level of LCR content, RP11-102O5 and RP11-497C14 showed additional fluorescence signals on chromosome 15q (Fig. 6B,C). The BAC clones RP11-722P3 and RP11-479B17 also showed a signal on Xqter (pseudoautosomal region 2) (Fig. 6D,E). Overall, these elements span the entire q12 region.

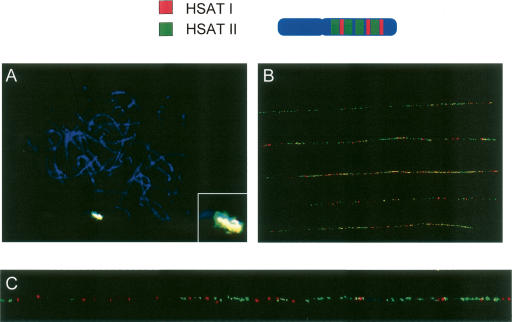

HSAT I is interspersed with HSAT II

We validated that HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich repeat maps to the heterochromatic region on chromosome Yq12 (Fig. 6). This is a region where human satellite II repeats are also found (Gosden et al. 1975b; Prosser et al. 1981). The HSAT II repeats are comprised of an irregular pentameric (GAATG)n, repeat, as mentioned above. To determine whether the two elements were interspersed or mapped to separate locations, we performed FISH mapping analysis using a BAC RP11-242E13 containing HSAT II (green) and the 400-bp HSAT I (red) probe. FISH mapping on metaphase cells of human male lymphocytes showed that HSAT I and HSAT II repeats overlap on chromosome Yq12 (Fig. 7A). To determine a more precise positioning of HSAT I with HSAT II, fiber-FISH was performed on chromosome Y (Fig. 7B). To make a suitable probe for fiber-FISH, a 1.7-kb region was amplified from the BAC clone RP11-242E13 containing HSAT II and then was subcloned. While both satellites’ sequences appear to be randomly interspersed within each other; HSAT II is more prevalent (Fig. 7B,C). The centromeric regions of the acrocentric chromosomes also contain heterochromatic regions with an abundance of satellite sequences, including alphoid and subfamilies of HSAT III (Jorgensen et al. 1987, 1988; Earle et al. 1992; Kalitsis et al. 1993; Trowell et al. 1993; Bandyopadhyay et al. 2001). To determine if there were any HSAT III sequences present, we performed FISH mapping analysis with one of the subfamilies of HSAT III. A weak signal was observed on pericentromeric Yq but not on Yq12 (data not shown). Signals were detected on p arms of acrocentric chromosomes as well (data not shown). Neither subfamily of HSAT II nor HSAT III was interspersed with HSAT I in the LCR22s, nor was this pattern present on the available sequence of chromosome 21p11.1. Thus, the organization of the satellites is not similar in the other chromosomes, suggesting that this organization is chromosome Yq12 specific or perhaps also specific for the centromeric regions of acrocentric chromosomes.

Figure 7.

HSAT I and HSAT II FISH mapping. (A) FISH mapping on metaphase human male peripheral lymphocytes stained with DAPI with HSAT II probe (green) and HSAT I (red) have an overlapping signal producing a yellow color. (B) Fiber-FISH on chromosome Y with HSAT I probe (red) and HSAT II (green), show more hybridization of HSAT II on the Yq12 region compared with HSAT I. There is no distinct pattern of hybridization of HSAT I and HSAT II; however, HSAT II hybridizes to a larger region of the Yq12 region. (C) An enlarged region of one of the DNA fiber strands from B.

Organization of individual HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich elements on Y

The 2.4-kb DNA tripartite SpeI fragment is similar on Yq12 as in the LCR22s was determined by subcloning and resequencing analysis. The 5′ part of the AT-rich array is composed of two ∼300-bp-long and 76% identical inverted repeats from a central point (Supplemental Fig. 2). It is possible that the sequence could form a cruciform. If a cruciform is formed, this could result in an unstable sequence creating single- or double-strand breaks, resulting in chromosome rearrangements and further duplication of the element.

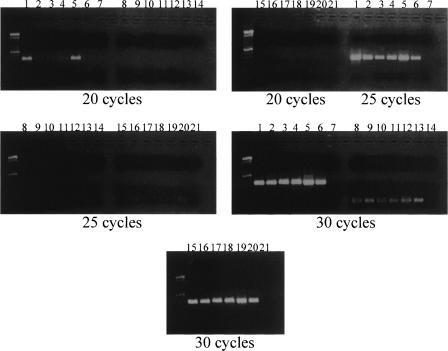

HSAT I elements are not present on chromosome Y in other hominoid species

The structure of chromosome Y is divergent among the hominoid species (Wimmer et al. 2002). To determine if the HSAT I repeats are also found on chromosome Y in other hominoid species, metaphase FISH mapping using the 400-bp HSAT I probe was performed on DNA from male orangutan, gorilla, and pygmy chimpanzee lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). In contrast to the strong hybridization signal found on the human chromosome Y, there was no hybridization of HSAT I to chromosome Y in these species using high- and low-stringency conditions (data not shown). HSAT I is present on the autosomes of other hominoid species such as gorilla and chimpanzee (Cooke et al. 1982), but not on chromosome Y. Examination of GenBank revealed HSAT I sequences present in chimpanzee (AC099533) and baboon (AC129096, AC090965). Semi-quantitative PCR using conserved HSAT I primers showed that the gorilla contains more HSAT I repeats than chimpanzee, pygmy, bonobo, and orangutan (Fig. 8). This suggests that copy number may be variable among hominoid species and may further demonstrate their instability in the genome. Since there may be more copies of HSAT I in gorilla compared with other hominoid species, expansion of HSAT I occurred after the divergence of gorillas to their common ancestor. The gorilla HSAT I was 94.72% identical to the human HSAT I consensus sequence found in the database.

Figure 8.

HSAT I semi-quantitative PCR on hominoid DNA. HSAT I, beta-catenin (CTNNB1), and SMARCB1 (viral integrase 1; two control primer sets) were used to amplify human, chimpanzee, pygmy, bonobo, gorilla, and orangutan DNA and then were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel. The PCR was done with increasing cycles 20, 25, and 30. (Lanes 1–7) HSAT I PCR, (lanes 8–14) CTNNB1, (lanes 15–21) SMARCB1. The lanes are human–chimpanzee–pygmy–bonobo–gorilla–orangutan–negative control for each PCR primer and each cycling condition. The control primers do not amplify at the low cycles very well. In the HSAT I PCR, human (1) and gorilla (5) have an increased amplification compared to the other species.

Discussion

In this report, we showed that a subclass of human satellite sequences, a 2.4-kb HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich tripartite repeat, is present in regions associated with human chromosome 22q11.2 rearrangement disorders as well as in heterochromatic regions, including the acrocentric chromosomes and Yq12. The AT-rich repeat is associated with constitutional translocations in humans and has shaped the LCR22 structure. Their recent duplication on Yq12 suggests that these elements may not only have a role in mediating chromosome rearrangements during meiosis, but they may also have contributed to the evolution of chromosome structure as well as disease-associated genomic rearrangements.

Formation and duplication of LCR22s

The LCR22s are a complex mosaic of blocks with >95% identical sequence that have formed during primate evolution. We described Alu-mediated recombination events as being responsible for rearrangements involving genes that comprise them (Babcock et al. 2003). However, we do not know how the LCR22s have become duplicated in their entirety, which appears to have been the case at least for LCR22-2 and LCR22-4. This is because they have almost identical block structure. In an attempt to infer mechanisms from evaluating the products of recombination, we examined the breakpoint at the ends of the two LCR22s. We found that the distal end of LCR22-2 occurs in the AT-rich repeat. This particular breakpoint is embedded within LCR22-4. Based upon analyzing the sequences at the ends and tracing the position of the breakpoints, we believe that the AT-rich repeat provided instability, perhaps via formation of double-stranded breaks in cruciform structures resulting in a duplication event. Thus, it is not surprising that we identified these elements in other unstable genomic regions, where other satellite sequences nucleate, in particular the pericentromeric regions of acrocentric chromosomes and the heterochromatic Yq12 interval. Alternatively, the fact that the AT-rich repeat is found at the LCR22-2 border only suggests that this repeat could have a special role in the formation and duplication of LCR22s; however, in fact it simply shows direct sequence evidence that a double-strand break has occurred in this sequence, as it was also the case for the sequence at the centromeric LCR22-2 border. Examination of LCR22 borders in primate species, in the future, will help clarify the role of the AT-rich repeat in mediating these rearrangements.

The tripartite element on chromosome Y

The expansion of the HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich tripartite repeat on human Yq12 is dramatic because, on the one hand, it comprises a large interval in humans; in contrast, it is absent on chromosome Y in other hominoid species (Gosden et al. 1977; Cooke et al. 1982; Kunkel and Smith 1982; Smith et al. 1987). Since there is no pairing partner for chromosome Y, the heterochromatic region Yq12 is supposed to escape meiotic recombination. In contrast, unequal recombination between sister chromatids is a likely mechanism responsible for the dramatic expansion of these repeats in humans. Thirty years ago, Smith (1976) proposed a mechanism of how DNA blocks can became amplified, thereby giving rise to large tandem arrays. In this mechanism, sister chromatid misalignment could result in an unequal random crossover between repeats of identical or near identical sequences, resulting in repeat block expansion or deletion. One point of interest is that the repeat in humans appears to be largely the same size and composition. Smith (1976) also explained how deletions and duplications can occur without changing the repeat pattern, as was observed by our Southern blot analysis of male DNA. Mutations arising within the array will likely be eliminated by deletion via unequal crossovers, followed by the addition of tandem duplication. Although all types of recombination are suppressed on chromosome Y, it must occur at sufficiently high levels to be detected in humans. Evidence for deletions and duplications in the heterochromatin on Yq12 have been recently described (Repping et al. 2006). The investigators measured the length of the Yq12 heterochromatin by using quinacrine staining in 47 men belonging to the major branches of genealogy and including worldwide diversity. It was found that the length of the Yq12 heterochromatic region varied in length from 29%–54% on the metaphase Y chromosome. Interestingly, the Yq12 region has also been involved in a few reported translocations (Nielsen and Rasmussen 1976; Curtis 1977). Since there are occasional translocations on the Yq12 region, it can be inferred that they might contain sequences that might induce recombination events.

How did the original HSATI/Alu/AT-rich repeat find its way to chromosome Yq12 to begin with? The acrocentric p11-q11 regions have not been completely cloned and sequenced. What is available, is a contig of genomic clones, which contains genes also validated by other methods to be present in the acrocentric centromeric regions, including TPTE (transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology). TPTE is exclusively and highly expressed in the testes and is believed to be involved in signal transduction. The TPTE gene is distributed in a handful of locations in the genome, including the acrocentric chromosomes as determined by PCR analysis of somatic hybrid cell lines (Chen et al. 1999). Adjacent to the TPTE gene is one copy of an HSATI/Alu/AT-rich repeat. There is no sequence available for the region immediately distal to the tripartite repeat. Of interest, a copy of the TPTE gene is present in the very distal end of the Yq11.23 region, juxtaposed to the uncloned Yq12 region. We hypothesize that meiotic unequal crossover between sister chromatids led to the tandem duplication of the repeat. The HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich repeat is present in a more complex arrangement on chromosome Yq12 as clusters that are interspersed by pentameric HSAT II elements, also present on 21p11. The organization of the Yq11.23-q12 junction might have formed initially via addition of sequences from 21p11, or another acrocentric chromosome, via perhaps a gene conversion event followed by a series of unequal crossovers.

Structural roles for HSAT repeats on Yq12.

As for most heterochromatin, the Yq12 region containing HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich repeats is located in the nuclear periphery during interphase. The specific location of chromosomes in the nucleus is still a debated issue. The position of the chromosome within the nucleus might be determined on the cell type, size of the chromosome, and/or the gene content (Cremer et al. 2001). In the same report using lymphoblast cells, which have spherical nuclei, it was shown that the long arm of the Y chromosome was associated with the nuclear periphery (Cremer et al. 2001). Consistent with this location, nontranscribed regions consistently lie at the nuclear periphery, while gene sequences lie more toward the interior region of the nucleus (Croft et al. 1999; Boyle et al. 2001). One report investigating the location of individual chromosomes within the nucleus, comparing the centromeric heterochromatin domains, revealed that for the chromosomes with larger heterochromatic blocks as assessed by enhanced staining using G-banding, the centromere is located closer to the nuclear periphery compared with chromosomes with a lighter G-banding near the centromere (Carvalho et al. 2001). Beyond these physical attributes of satellite repeats, condensed heterochromatin and peripheral location within the nucleus, its potential function is not known. Perhaps this location in the nuclear periphery, away from most other chromosomes, prevents recombination or translocations between highly unstable satellite repeats between other chromosomes, thereby increasing meiotic stability.

In conclusion, HSAT I/Alu/AT-rich regions are more predominant then previously believed. They likely have a role in mediating balanced translocations during meiosis and possibly have structural roles. These elements may also have had a potential role in altering the genomic architecture both on chromosome Y and the acrocentric autosomes.

Methods

Isolation of total human genomic DNA

Genomic DNA were prepared from peripheral blood and isolated using the Puregene system (Gentra Corp.). Chromosome Y hamster–human somatic cell hybrid, cell line GM06317, was purchased through the Coriell Cell Repository (NIGMS). The cell line was maintained under the conditions provided by Coriell, and DNA was extracted using the Puregene system (Gentra).

Selection and isolation of BAC DNA for FISH mapping

The BAC clones for FISH mapping were chosen based upon their position in the human genome sequence (UCSC Browser, May 2004 [build 35]) and were purchased from the Children’s Hospital Oakland–BACPAC Resources. Two Yq11.23 BAC clones mapping ∼26 Mb from Ypter and centromeric to the Yq12 heterochromatin, RP11-102O5 (AC006328) and RP11-497C14 (AC007562), were used to determine the position of HSAT I. Two Yq12 pseudoautosomal region 2–specific BAC clones, RP11-722P3 (AQ513745, AQ494321) and RP11-479B17 (AQ629319, AQ629322), that map 0.2 Mb from Yqter and telomeric to the Yq12 heterochromatin were also used to validate map positions along Yq12. All four BACs were cohybridized separately with the HSAT I–specific probes. BAC clone RP11-242E13 that maps to the Yq12 region and contains a satellite sequence, HSAT II, was used to determine the relative location of HSAT I as compared to HSAT II. The DNA was prepared from each BAC using the Nucleobond kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of HSAT I and HSAT II probes as well as utilization of HSAT III probes

Male total genomic DNA from Epstein-Barr virus transformed LCLs was digested with SpeI, yielding a 2.4-kb restriction fragment, which was then isolated and cloned into a SpeI-digested pBluescript plasmid (Stratagene). Colony hybridization was performed by transferring the colonies to nylon transfer membranes (Amersham). The colonies were screened using the α32P-dCTP–labeled 400-bp HSAT I PCR product (HSAT IF-TAATGT GTGGGCTTGGGATT; HSAT IR-TGCATATGGAAAATACAGAG GCTA) probe, and positive colonies were isolated. The selected clones were termed clone 1, clone 2 (T6), and clone 3 (T17). The purified clone DNA was used as a probe for genomic Southern blot hybridization and FISH mapping. A 1.7-kb HSAT II sequence was generated by PCR amplification using HSAT IIF-TTCGATCCCATTCCTTTCAA and HSAT IIR-CGACTGGTACG GACTCCAAT using BAC RP11-242E13 as a template. The 1.7-kb fragment was subcloned and used as a probe for FISH mapping. HSAT III probes, pR-1 and pR-4 (Group 2 sequences), were as described in Bandyopadhyay et al. (2001). The PCR primer pairs for each of these probes amplify primarily GGAAT motifs.

Genomic Southern hybridization

Human genomic DNA digested with SpeI was electrophoresed on 0.8% agarose TAE gel overnight at 40 V and then transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham). The Southern hybridization blot was prehybridized for 1 h at 65°C in CG buffer (7% SDS/1% BSA/0.5 M phosphate) and then hybridized with the radiolabeled probe overnight at 65°C in the same solution. The probes were labeled with α32P-dCTP through random priming using Rediprime II (Amersham) and purified with the G-50 columns (Amersham). The filters were washed three times in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 min at 62°C. The filters were exposed to Kodak Ultrasensitive film X_OMAT AR for varying times either at room temperature or −80°C. The film was quantitated using the Kodak Image Station 1000 with the Kodak 1D 3.6 software.

Sequencing of the 2.4-kb HSAT I subclones

The following primers were used for sequencing HSAT I subclones (5′-3′): HSAT I F-TAATGTGTGGGCTTGGGATT, HSAT I R-TGCATATGGAAAATACAGAGGCTA, HSAT II F-TTCGAT CCCATTCCTTTCAA, HSAT INT R2-ATAATATTGTTTTACATC CTGCG, HSAT INT R1-ATAATATTGTTTTACATCCTGCG, HSAT INT R2-GCATTATATTTATACAATATGAC, HSAT AT 1F-GTTATATGTAATTTTATTACTTAC, HSAT AT 2F-ATCA CATAATATATGTTACCTAC, HSAT AT 3R-CGTATATACTATAT CATATGTG, HSAT I R-TGCATATGGAAAATACAGAGGCTA, HSAT I (LCR2NUM1) F-GCCTCTGTATTTTCCATATGCAGT, T3-ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGA, and T7-TAATACGACTCAC TATAGGGAGA. The HSAT I subclones clone 1, clone 2 (T6), and clone 3 (T17) were sequenced and analyzed using the Sequencher 4.1 Program. Sequences were also aligned using MAFFT (Katoh et al. 2005). RepeatMasker (A.F.A. Smit and P. Green, unpubl., http://www.repeatmasker.org/), Repbase Update libraries (Jurka et al. 2005), and TandemRepeatFinder (Benson 1999) were used to identify repetitive elements. We used the einverted program from the EMBOSS package (Rice et al. 2000) to detect potential palindromes. Phylogeny was determined as described (Galtier et al. 1996).

FISH mapping

LCLs from humans and nonhuman primate species were grown and harvested using standard methods. The male pygmy chimp (Pan paniscus) lymphoblast sample was kindly provided by Dr. D. Nelson from Baylor College of Medicine, and the male lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla, CRL 1854) and orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; http://www.atcc.org/). FISH mapping was performed on metaphase and interphase cells as described (Shaffer et al. 1997). Fiber-FISH experiments with PCR products and BAC clones as probes were performed according to Heiskanen et al. (1994). Briefly, nick-translated flurophore-labeled isolated BAC clones (200 ng) or PCR products DNA (100 ng) were used as probes. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI diluted in Vectashield antifade (Vector Labs). Cells and chromatin fibers were viewed under a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope equipped with an appropriate filter combination and CCD camera. Monochromatic images were captured and pseudocolored using MacProbe 4.2.2 (Perceptive Scientific Instruments) on a Power Macintosh G4 system.

Semi-quantitative PCR

PCR was performed on the hominoid DNA samples, P. paniscus (bonobo, male-NG05253), G. gorilla (Western lowland gorilla, female-NG05251), P. pygmaeus abelii (Sumatran orangutan, female-NG12256), and Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee, male-NG06939), that were purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (NIGMS). Human placenta DNA (Sigma) was also used in the semi-quantitative PCR. The HSAT I F/R primers were used for 10 min at 94°C, followed by (30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 58°C, and 30 sec at 72°C), and 10 min at 72°C. The cycles varied from 20, 25, 30, and 35. The PCR conditions were at 2.5 mM Mg, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μM of each primer, and 0.04 units of Fast Start High Fidelity Taq (Roche). Two sets of control primers were also used, beta-catenin and SMARCB1 (Ini1): beta-catenin ex2 F- TCACTGGCAGCAA CAGTCTT; beta-catenin ex2R-CAGGACTTGGGAGGTATCCA; INI1 ex4F-AGAGGAACAGCCAGTGGGTA; INI1 ex4R- GGGG GAAGGTTCTCTTCTTG.

PCR analysis of DNA from the hamster–human somatic hybrid panel

The hamster–human somatic hybrid panel of DNA each containing one different human chromosome per cell line was purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (NIGMS Human/Rodent Somatic Cell Hybrid Mapping Panel 2). A total of 40 ng of DNA was amplified using HSAT I F/R with the above conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Adam Pavlicek at GIRI for computational assistance in analyzing the AT-rich repeats in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 regarding identification of the position of the breakpoints (Fig. 3). We also thank him for providing the data for Supplemental Figure 1. B.E.M. and J.R.L. are supported by P01 HD39420.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.5651507

References

- Babcock M., Pavlicek A., Spiteri E., Kashork C.D., Ioshikhes I., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Pavlicek A., Spiteri E., Kashork C.D., Ioshikhes I., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Spiteri E., Kashork C.D., Ioshikhes I., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Kashork C.D., Ioshikhes I., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Ioshikhes I., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Shaffer L.G., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Jurka J., Morrow B.E., Morrow B.E. Shuffling of genes within low-copy repeats on 22q11 (LCR22) by Alu-mediated recombination events during evolution. Genome Res. 2003;13:2519–2532. doi: 10.1101/gr.1549503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J.A., Gu Z., Clark R.A., Reinert K., Samonte R.V., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Gu Z., Clark R.A., Reinert K., Samonte R.V., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Clark R.A., Reinert K., Samonte R.V., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Reinert K., Samonte R.V., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Samonte R.V., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Schwartz S., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Li P.W., Eichler E.E., Eichler E.E. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J.A., Liu G., Eichler E.E., Liu G., Eichler E.E., Eichler E.E. An Alu transposition model for the origin and expansion of human segmental duplications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:823–834. doi: 10.1086/378594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay R., McQuillan C., Page S.L., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., McQuillan C., Page S.L., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., Page S.L., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., Shaffer L.G. Identification and characterization of satellite III subfamilies to the acrocentric chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 2001;9:223–233. doi: 10.1023/a:1016648404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle S., Gilchrist S., Bridger J.M., Mahy N.L., Ellis J.A., Bickmore W.A., Gilchrist S., Bridger J.M., Mahy N.L., Ellis J.A., Bickmore W.A., Bridger J.M., Mahy N.L., Ellis J.A., Bickmore W.A., Mahy N.L., Ellis J.A., Bickmore W.A., Ellis J.A., Bickmore W.A., Bickmore W.A. The spatial organization of human chromosomes within the nuclei of normal and emerin-mutant cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:211–219. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C., Sirotkin H., Pandita R., Goldberg R., McKie J., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Sirotkin H., Pandita R., Goldberg R., McKie J., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Pandita R., Goldberg R., McKie J., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Goldberg R., McKie J., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., McKie J., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Wadey R., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Patanjali S.R., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Weissman S.M., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Anyane-Yeboa K., Warburton D., Warburton D., et al. Molecular definition of 22q11 deletions in 151 velo-cardio-facial syndrome patients. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:620–629. doi: 10.1086/515508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C., Pereira H.M., Ferreira J., Pina C., Mendonca D., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Pereira H.M., Ferreira J., Pina C., Mendonca D., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Ferreira J., Pina C., Mendonca D., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Pina C., Mendonca D., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Mendonca D., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Rosa A.C., Carmo-Fonseca M., Carmo-Fonseca M. Chromosomal G-dark bands determine the spatial organization of centromeric heterochromatin in the nucleus. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3563–3572. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Rossier C., Morris M.A., Scott H.S., Gos A., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Rossier C., Morris M.A., Scott H.S., Gos A., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Morris M.A., Scott H.S., Gos A., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Scott H.S., Gos A., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Gos A., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Bairoch A., Antonarakis S.E., Antonarakis S.E. A testis-specific gene, TPTE, encodes a putative transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase and maps to the pericentromeric region of human chromosomes 21 and 13, and to chromosomes 15, 22, and Y. Hum. Genet. 1999;105:399–409. doi: 10.1007/s004390051122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke H.J., Schmidtke J., Gosden J.R., Schmidtke J., Gosden J.R., Gosden J.R. Characterisation of a human Y chromosome repeated sequence and related sequences in higher primates. Chromosoma. 1982;87:491–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00333470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer M., von Hase J., Volm T., Brero A., Kreth G., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., von Hase J., Volm T., Brero A., Kreth G., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Volm T., Brero A., Kreth G., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Brero A., Kreth G., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Kreth G., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Walter J., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Fischer C., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Solovei I., Cremer C., Cremer T., Cremer C., Cremer T., Cremer T. Non-random radial higher-order chromatin arrangements in nuclei of diploid human cells. Chromosome Res. 2001;9:541–567. doi: 10.1023/a:1012495201697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft J.A., Bridger J.M., Boyle S., Perry P., Teague P., Bickmore W.A., Bridger J.M., Boyle S., Perry P., Teague P., Bickmore W.A., Boyle S., Perry P., Teague P., Bickmore W.A., Perry P., Teague P., Bickmore W.A., Teague P., Bickmore W.A., Bickmore W.A. Differences in the localization and morphology of chromosomes in the human nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1119–1131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis D.J. Meiotic chromosomes in an infertile male with an unbalanced Y/13 translocation. Hum. Genet. 1977;37:249–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00393605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle E., Shaffer L.G., Kalitsis P., McQuillan C., Dale S., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., Kalitsis P., McQuillan C., Dale S., Choo K.H., Kalitsis P., McQuillan C., Dale S., Choo K.H., McQuillan C., Dale S., Choo K.H., Dale S., Choo K.H., Choo K.H. Identification of DNA sequences flanking the breakpoint of human t(14q21q) Robertsonian translocations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;50:717–724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann L., Spiteri E., McCain N., Goldberg R., Pandita R.K., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Spiteri E., McCain N., Goldberg R., Pandita R.K., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., McCain N., Goldberg R., Pandita R.K., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Goldberg R., Pandita R.K., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Pandita R.K., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Duong S., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Fox J., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Blumenthal D., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Lalani S.R., Shaffer L.G., Shaffer L.G., et al. A common breakpoint on 11q23 in carriers of the constitutional t(11;22) translocation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1608–1616. doi: 10.1086/302689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann L., Spiteri E., Koren K., Pulijaal V., Bialer M.G., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Spiteri E., Koren K., Pulijaal V., Bialer M.G., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Koren K., Pulijaal V., Bialer M.G., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Pulijaal V., Bialer M.G., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Bialer M.G., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Shanske A., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Goldberg R., Morrow B.E., Morrow B.E. AT-rich palindromes mediate the constitutional t(11;22) translocation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1–13. doi: 10.1086/316952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensenauer R.E., Adeyinka A., Flynn H.C., Michels V.V., Lindor N.M., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Adeyinka A., Flynn H.C., Michels V.V., Lindor N.M., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Flynn H.C., Michels V.V., Lindor N.M., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Michels V.V., Lindor N.M., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Lindor N.M., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Dawson D.B., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Thorland E.C., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Lorentz C.P., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., Goldstein J.L., McDonald M.T., McDonald M.T., et al. Microduplication 22q11.2, an emerging syndrome: Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular analysis of thirteen patients. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1027–1040. doi: 10.1086/378818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccaro M., Lindsten J., Ford C.E., Iselius L., Lindsten J., Ford C.E., Iselius L., Ford C.E., Iselius L., Iselius L. The 11q;22q translocation: A European collaborative analysis of 43 cases. Hum. Genet. 1980;56:21–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00281567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M., Prosser J., Tkachuk D., Reisner A.H., Vincent P.C., Prosser J., Tkachuk D., Reisner A.H., Vincent P.C., Tkachuk D., Reisner A.H., Vincent P.C., Reisner A.H., Vincent P.C., Vincent P.C. Simple repeated sequences in human satellite DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:547–563. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M., Prosser J., Vincent P.C., Prosser J., Vincent P.C., Vincent P.C. Human satellite I sequences include a male specific 2.47 kb tandemly repeated unit containing one Alu family member per repeat. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2887–2900. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.6.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke B., Edelmann L., McCain N., Pandita R.K., Ferreira J., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Edelmann L., McCain N., Pandita R.K., Ferreira J., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., McCain N., Pandita R.K., Ferreira J., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Pandita R.K., Ferreira J., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Ferreira J., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Merscher S., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Zohouri M., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Cannizzaro L., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Shanske A., Morrow B.E., Morrow B.E. Der(22) syndrome and velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome share a 1.5-Mb region of overlap on chromosome 22q11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:747–758. doi: 10.1086/302284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N., Gouy M., Gautier C., Gouy M., Gautier C., Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: Two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosden J.R., Buckland R.A., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Buckland R.A., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Evans H.J. Chromosomal localisation of DNA sequences in condensed and dispersed human chromatin. Exp. Cell Res. 1975a;92:138–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosden J.R., Mitchell A.R., Buckland R.A., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Mitchell A.R., Buckland R.A., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Buckland R.A., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Clayton R.P., Evans H.J., Evans H.J. The location of four human satellite DNAs on human chromosomes. Exp. Cell Res. 1975b;92:148–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90648-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosden J.R., Mitchell A.R., Seuanez H.N., Gosden C.M., Mitchell A.R., Seuanez H.N., Gosden C.M., Seuanez H.N., Gosden C.M., Gosden C.M. The distribution of sequences complementary to human satellite DNAs I, II and IV in the chromosomes of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) and orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) Chromosoma. 1977;63:253–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00327453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen M., Karhu R., Hellsten E., Peltonen L., Kallioniemi O.P., Palotie A., Karhu R., Hellsten E., Peltonen L., Kallioniemi O.P., Palotie A., Hellsten E., Peltonen L., Kallioniemi O.P., Palotie A., Peltonen L., Kallioniemi O.P., Palotie A., Kallioniemi O.P., Palotie A., Palotie A. High resolution mapping using fluorescence in situ hybridization to extended DNA fibers prepared from agarose-embedded cells. Biotechniques. 1994;17:928–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki H., Ohye T., Kogo H., Yamada K., Kowa H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Ohye T., Kogo H., Yamada K., Kowa H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kogo H., Yamada K., Kowa H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Yamada K., Kowa H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kowa H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Shaikh T.H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kurahashi H. Palindromic AT-rich repeat in the NF1 gene is hypervariable in humans and evolutionarily conserved in primates. Hum. Mutat. 2005;26:332–342. doi: 10.1002/humu.20228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen A.L., Bostock C.J., Bak A.L., Bostock C.J., Bak A.L., Bak A.L. Homologous subfamilies of human alphoid repetitive DNA on different nucleolus organizing chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:1075–1079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen A.L., Kolvraa S., Jones C., Bak A.L., Kolvraa S., Jones C., Bak A.L., Jones C., Bak A.L., Bak A.L. A subfamily of alphoid repetitive DNA shared by the NOR-bearing human chromosomes 14 and 22. Genomics. 1988;3:100–109. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J., Kapitonov V.V., Pavlicek A., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J., Kapitonov V.V., Pavlicek A., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J., Pavlicek A., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J., Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalitsis P., Earle E., Vissel B., Shaffer L.G., Choo K.H., Earle E., Vissel B., Shaffer L.G., Choo K.H., Vissel B., Shaffer L.G., Choo K.H., Shaffer L.G., Choo K.H., Choo K.H. A chromosome 13-specific human satellite I DNA subfamily with minor presence on chromosome 21: Further studies on Robertsonian translocations. Genomics. 1993;16:104–112. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Inagaki H., Yamada K., Kogo H., Ohye T., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Inagaki H., Yamada K., Kogo H., Ohye T., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Yamada K., Kogo H., Ohye T., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kogo H., Ohye T., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Ohye T., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kowa H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Nagaoka K., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Taniguchi M., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Emanuel B.S., Kurahashi H., Kurahashi H. Genetic variation affects de novo translocation frequency. Science. 2006;311:971. doi: 10.1126/science.1121452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Kuma K., Toh H., Miyata T., Kuma K., Toh H., Miyata T., Toh H., Miyata T., Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: Improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H., Haussler J., Krone W., Bode H., Jenne D.E., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Haussler J., Krone W., Bode H., Jenne D.E., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Krone W., Bode H., Jenne D.E., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Bode H., Jenne D.E., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Jenne D.E., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Mehnert K.U., Tummers U., Assum G., Tummers U., Assum G., Assum G. The second case of a t(17;22) in a family with neurofibromatosis type 1: Sequence analysis of the breakpoint regions. Hum. Genet. 1997;99:237–247. doi: 10.1007/s004390050346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Zahler A.M., Haussler D., Haussler D. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel L.M., Smith K.D., Smith K.D. Evolution of human Y-chromosome DNA. Chromosoma. 1982;86:209–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00288677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahashi H., Shaikh T.H., Hu P., Roe B.A., Emanuel B.S., Budarf M.L., Shaikh T.H., Hu P., Roe B.A., Emanuel B.S., Budarf M.L., Hu P., Roe B.A., Emanuel B.S., Budarf M.L., Roe B.A., Emanuel B.S., Budarf M.L., Emanuel B.S., Budarf M.L., Budarf M.L. Regions of genomic instability on 22q11 and 11q23 as the etiology for the recurrent constitutional t(11;22) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1665–1670. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludena P., Fernandez-Piqueras J., Sentis C., Fernandez-Piqueras J., Sentis C., Sentis C. Distribution of DYZ2 repetitive sequences on the human Y chromosome. Hum. Genet. 1993;90:572–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00217462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermid H.E., Morrow B.E., Morrow B.E. Genomic disorders on 22q11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1077–1088. doi: 10.1086/340363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay R.D., Heritage J., Bobrow M., Cooke H.J., Heritage J., Bobrow M., Cooke H.J., Bobrow M., Cooke H.J., Cooke H.J. Enduclease analysis of Y chromosome DNA. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1978;22:357–358. doi: 10.1159/000130971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow B., Goldberg R., Carlson C., Das Gupta R., Sirotkin H., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Goldberg R., Carlson C., Das Gupta R., Sirotkin H., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Carlson C., Das Gupta R., Sirotkin H., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Das Gupta R., Sirotkin H., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Sirotkin H., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Collins J., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Dunham I., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., O’Donnell H., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Scambler P., Shprintzen R., Shprintzen R., et al. Molecular definition of the 22q11 deletions in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:1391–1403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., Rasmussen K., Rasmussen K. Y/autosomal translocations. Clin. Genet. 1976;9:609–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1976.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser J., Reisner A.H., Bradley M.L., Ho K., Vincent P.C., Reisner A.H., Bradley M.L., Ho K., Vincent P.C., Bradley M.L., Ho K., Vincent P.C., Ho K., Vincent P.C., Vincent P.C. Buoyant density and hybridization analysis of human DNA sequences, including three satellite DNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;656:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(81)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser J., Frommer M., Paul C., Vincent P.C., Frommer M., Paul C., Vincent P.C., Paul C., Vincent P.C., Vincent P.C. Sequence relationships of three human satellite DNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;187:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repping S., van Daalen S.K., Brown L.G., Korver C.M., Lange J., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., van Daalen S.K., Brown L.G., Korver C.M., Lange J., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Brown L.G., Korver C.M., Lange J., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Korver C.M., Lange J., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Lange J., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Marszalek J.D., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Pyntikova T., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., van der Veen F., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Skaletsky H., Page D.C., Page D.C., et al. High mutation rates have driven extensive structural polymorphism among human Y chromosomes. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:463–467. doi: 10.1038/ng1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A., Longden I., Bleasby A., Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruault M., Ventura M., Galtier N., Brun M.E., Archidiacono N., Roizes G., De Sario A., Ventura M., Galtier N., Brun M.E., Archidiacono N., Roizes G., De Sario A., Galtier N., Brun M.E., Archidiacono N., Roizes G., De Sario A., Brun M.E., Archidiacono N., Roizes G., De Sario A., Archidiacono N., Roizes G., De Sario A., Roizes G., De Sario A., De Sario A. BAGE genes generated by juxtacentromeric reshuffling in the Hominidae lineage are under selective pressure. Genomics. 2003;81:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann M.O., Tajbakhsh J., Kurz A., Saracoglu K., Eils R., Lichter P., Tajbakhsh J., Kurz A., Saracoglu K., Eils R., Lichter P., Kurz A., Saracoglu K., Eils R., Lichter P., Saracoglu K., Eils R., Lichter P., Eils R., Lichter P., Lichter P. Topology of genes and nontranscribed sequences in human interphase nuclei. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;301:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Guttenbach M., Nanda I., Studer R., Epplen J.T., Guttenbach M., Nanda I., Studer R., Epplen J.T., Nanda I., Studer R., Epplen J.T., Studer R., Epplen J.T., Epplen J.T. Organization of DYZ2 repetitive DNA on the human Y chromosome. Genomics. 1990;6:212–218. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90559-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke J., Schmid M., Schmid M. Regional assignment of a 2.1-kb repetitive sequence to the distal part of the human Y heterochromatin. Hum. Genet. 1980;55:255–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00291774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer L.G., Kennedy G.M., Spikes A.S., Lupski J.R., Kennedy G.M., Spikes A.S., Lupski J.R., Spikes A.S., Lupski J.R., Lupski J.R. Diagnosis of CMT1A duplications and HNPP deletions by interphase FISH: Implications for testing in the cytogenetics laboratory. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;69:325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh T.H., Kurahashi H., Saitta S.C., O’Hare A.M., Hu P., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Kurahashi H., Saitta S.C., O’Hare A.M., Hu P., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Saitta S.C., O’Hare A.M., Hu P., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., O’Hare A.M., Hu P., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Hu P., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Roe B.A., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Driscoll D.A., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Zackai E.H., Budarf M.L., Budarf M.L., et al. Chromosome 22-specific low copy repeats and the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Genomic organization and deletion endpoint analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:489–501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.P. Evolution of repeated DNA sequences by unequal crossover. Science. 1976;191:528–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1251186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.D., Young K.E., Talbot C.C., Jr., Schmeckpeper B.J., Young K.E., Talbot C.C., Jr., Schmeckpeper B.J., Talbot C.C., Jr., Schmeckpeper B.J., Schmeckpeper B.J. Repeated DNA of the human Y chromosome. Development. 1987;101:77–92. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.Supplement.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri E., Babcock M., Kashork C.D., Wakui K., Gogineni S., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Babcock M., Kashork C.D., Wakui K., Gogineni S., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Kashork C.D., Wakui K., Gogineni S., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Wakui K., Gogineni S., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Gogineni S., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Lewis D.A., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Williams K.M., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Minoshima S., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Sasaki T., Shimizu N., Shimizu N., et al. Frequent translocations occur between low copy repeats on chromosome 22q11.2 (LCR22s) and telomeric bands of partner chromosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1823–1837. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowell H.E., Nagy A., Vissel B., Choo K.H., Nagy A., Vissel B., Choo K.H., Vissel B., Choo K.H., Choo K.H. Long-range analyses of the centromeric regions of human chromosomes 13, 14 and 21: Identification of a narrow domain containing two key centromeric DNA elements. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993;2:1639–1649. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer R., Kuhl H., Rottger S., Schempp W., Kuhl H., Rottger S., Schempp W., Rottger S., Schempp W., Schempp W. Comparative mapping of CDY and DAZ in higher primates. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2002;96:287–289. doi: 10.1159/000063021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackai E.H., Emanuel B.S., Emanuel B.S. Site-specific reciprocal translocation, t(11;22) (q23;q11), in several unrelated families with 3:1 meiotic disjunction. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1980;7:507–521. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320070412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]