Abstract

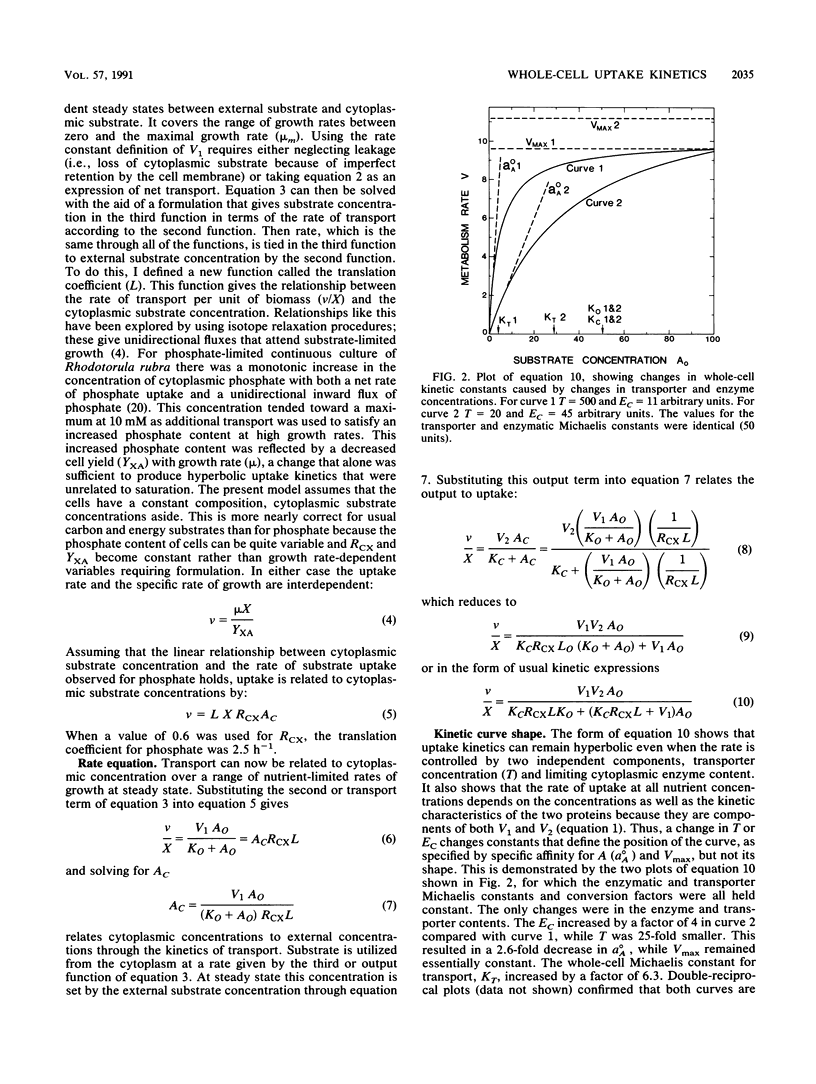

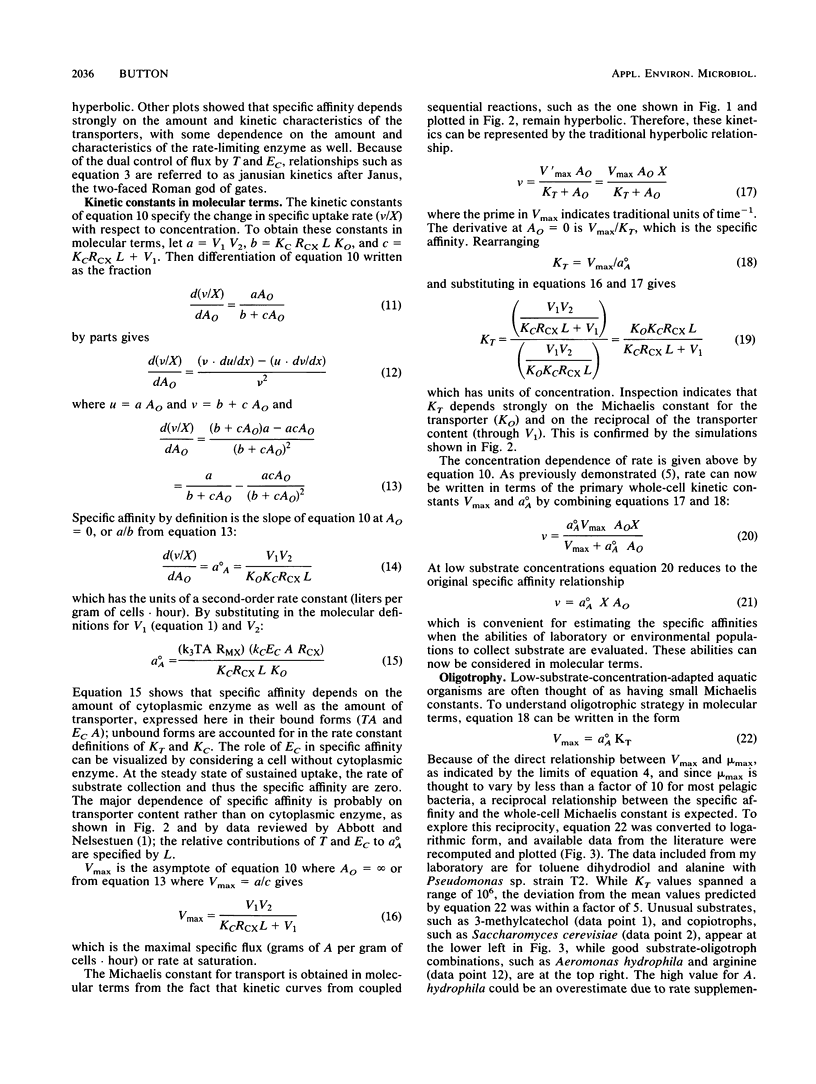

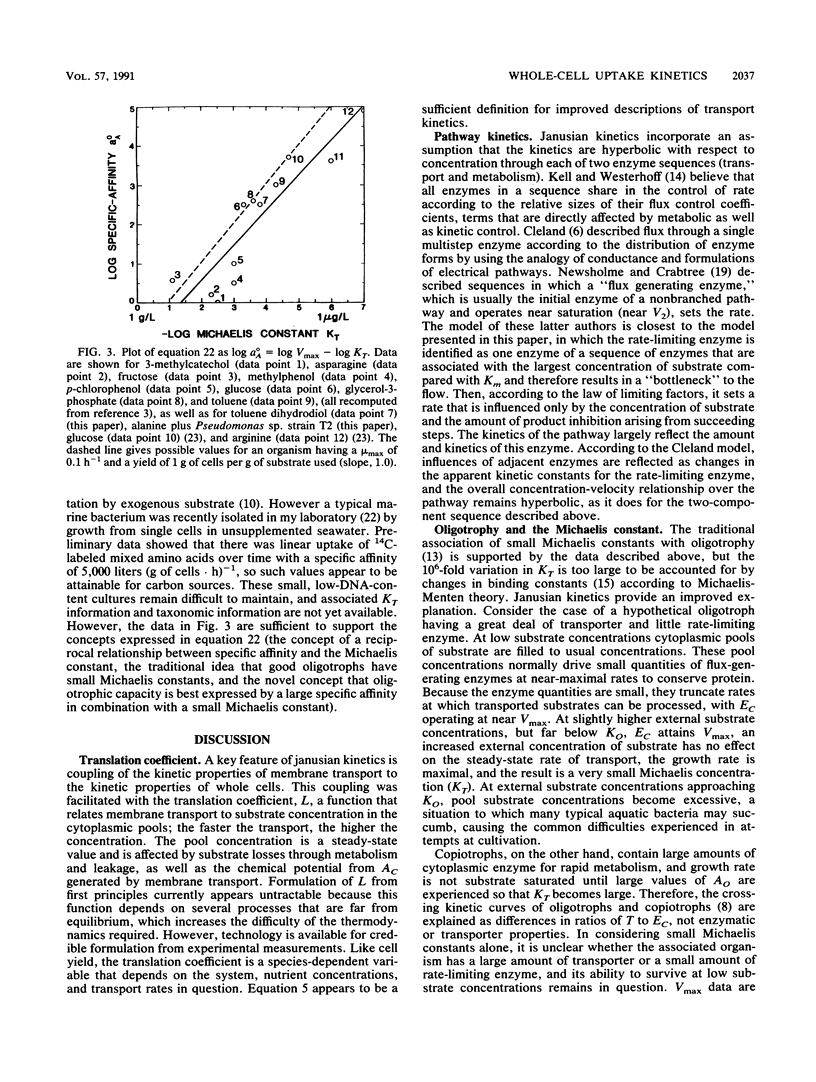

Formulations are presented that describe the concentration dependency of nutrient-limited transport and growth in molecular terms. They relate the rate of transport at steady state through a two-sequence process, transport and metabolism, to ambient concentrations according to the amounts and kinetic characteristics of the two rate-limiting proteins in these sequences. Sequences are separated by a metabolic pool. A novel feature of these formulations is the translation coefficient, which relates the transport rate attained at given ambient nutrient concentrations and membrane transporter characteristics to the nutrient concentrations sustained in the metabolic pools. The formulations, termed janusian kinetics, show that hyperbolic kinetics are retained during independent changes in transporter and enzyme contents or characteristics. Specific affinity (a°A) depends strongly on the amount and kinetic characteristics of the transporters; it is also mildly affected by the amount and characteristics of the rate-limiting enzyme. This kinetic constant best describes the ability to accumulate substrate from limiting concentrations. Maximal velocity (Vmax) describes uptake from concentrated solutions and can depend strongly on either limiting enzyme content or the associated content of transporters. The whole-cell Michaelis constant (KT), which depends on the ratio of rate-limiting enzyme to transporter, can be relatively independent of change in a°A and is best used to describe the concentration at which saturation begins to occur. Theory specifies that good oligotrophs have a large a°A for nutrient collection and a small Vmax for economy of enzyme, giving a small KT. The product of the two constants is universally rather constant so that oligotrophy is scaled on a plot of a°A versus KT, with better oligotrophs toward one end. This idea is borne out by experimental data, and therefore typical small difficult-to-culture aquatic bacteria may be classified as oligobacteria.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abbott A. J., Nelsestuen G. L. The collisional limit: an important consideration for membrane-associated enzymes and receptors. FASEB J. 1988 Oct;2(13):2858–2866. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.13.2844615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D. K. Kinetics of nutrient-limited transport and microbial growth. Microbiol Rev. 1985 Sep;49(3):270–297. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.3.270-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D. K., Robertson B. R. Kinetics of bacterial processes in natural aquatic systems based on biomass as determined by high-resolution flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1989 Sep;10(5):558–563. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W. W. Partition analysis and the concept of net rate constants as tools in enzyme kinetics. Biochemistry. 1975 Jul 15;14(14):3220–3224. doi: 10.1021/bi00685a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller A. Growth of bacteria in inorganic medium at different levels of airborne organic substances. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Dec;46(6):1258–1262. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1258-1262.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschal J. C. Some reflections on microbial competitiveness among heterotrophic bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1985;51(5-6):473–494. doi: 10.1007/BF00404494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut J. How do enzymes work? Science. 1988 Oct 28;242(4878):533–540. doi: 10.1126/science.3051385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupka R. M. Testing transport models and transport data by means of kinetic rejection criteria. Biochem J. 1989 Jun 15;260(3):885–891. doi: 10.1042/bj2600885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law A. T., Button D. K. Multiple-carbon-source-limited growth kinetics of a marine coryneform bacterium. J Bacteriol. 1977 Jan;129(1):115–123. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.1.115-123.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B. R., Button D. K. Phosphate-limited continuous culture of Rhodotorula rubra: kinetics of transport, leakage, and growth. J Bacteriol. 1979 Jun;138(3):884–895. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.884-895.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B. R., Button D. K. Toluene induction and uptake kinetics and their inclusion in the specific-affinity relationship for describing rates of hydrocarbon metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Sep;53(9):2193–2205. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2193-2205.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. Nutritional versatility and growth kinetics of an Aeromonas hydrophila strain isolated from drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988 Nov;54(11):2842–2851. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.11.2842-2851.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]