Abstract

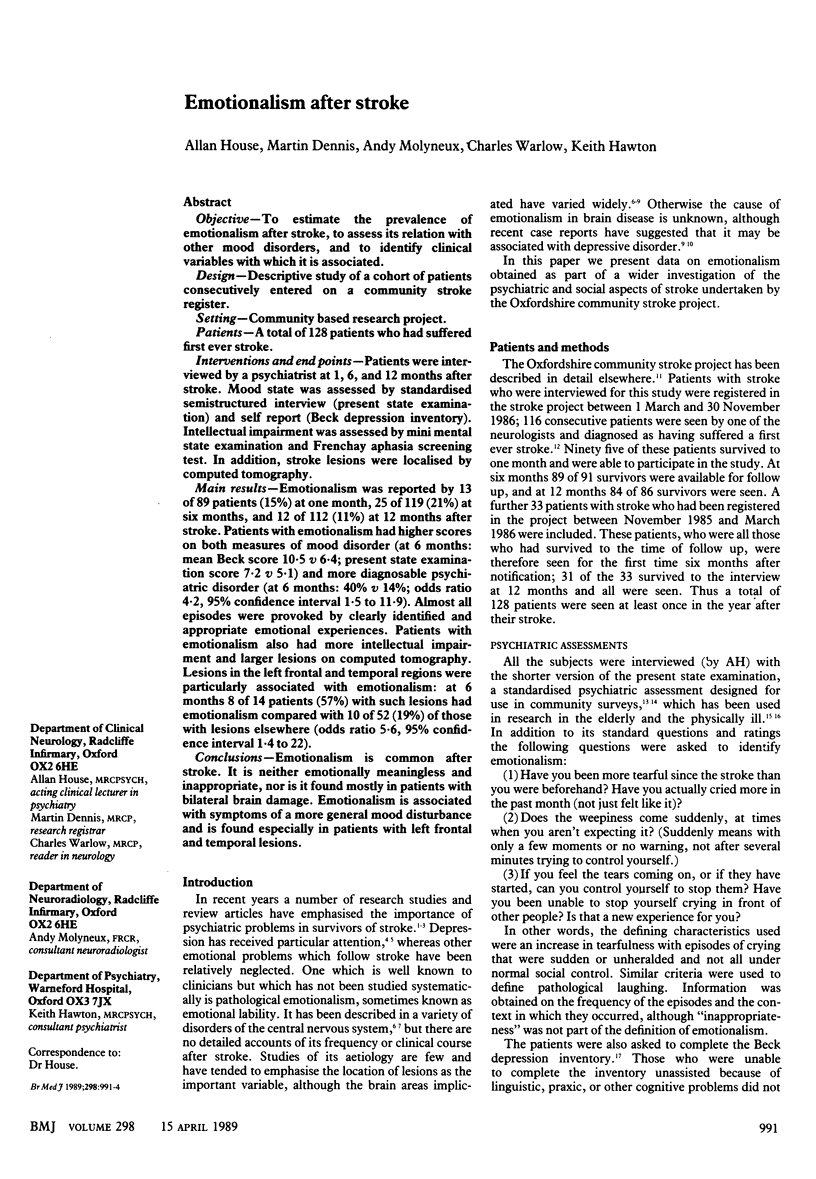

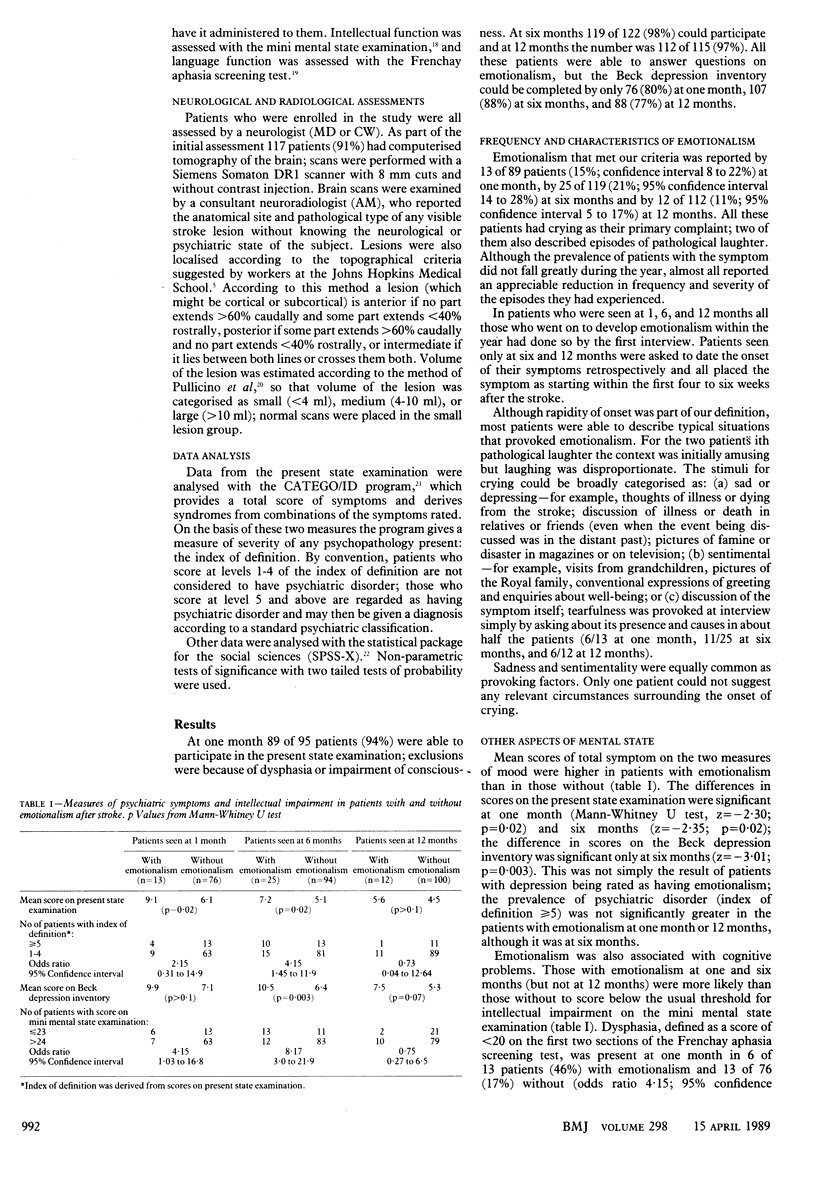

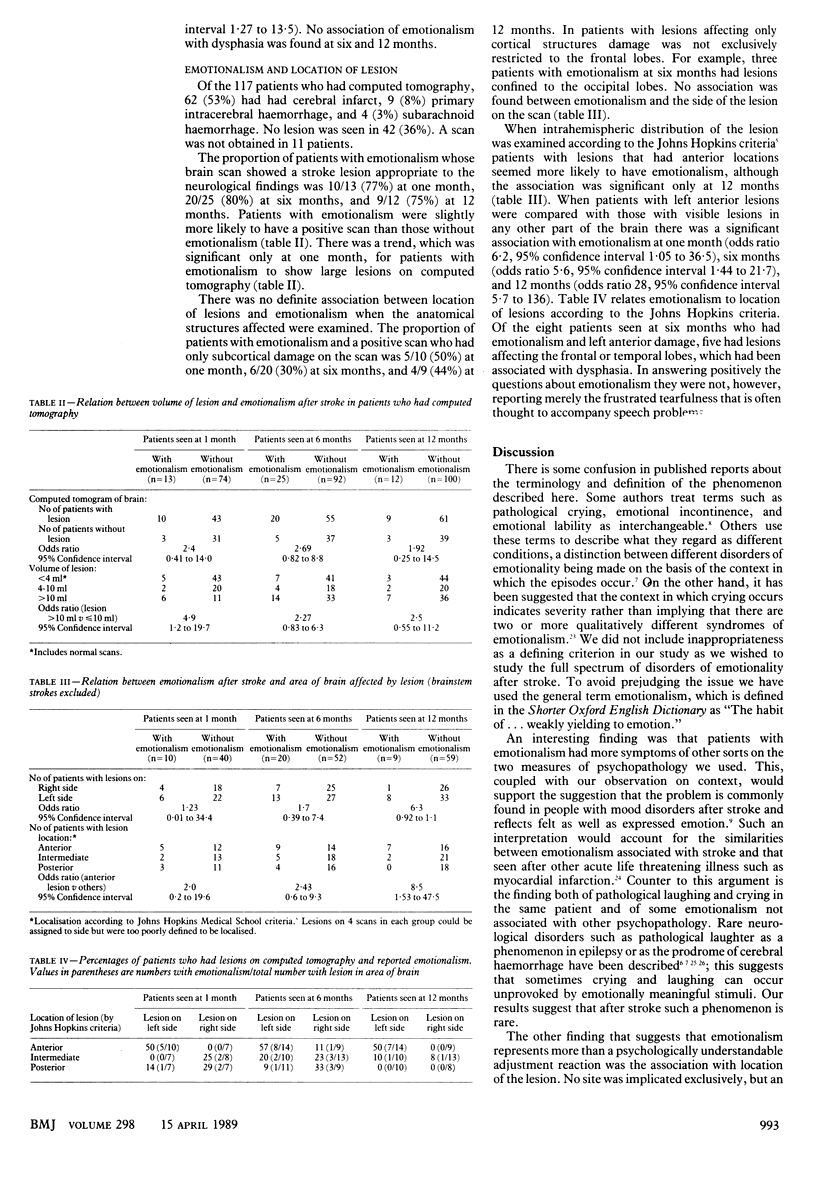

OBJECTIVE--To estimate the prevalence of emotionalism after stroke, to assess its relation with other mood disorders, and to identify clinical variables with which it is associated. DESIGN--Descriptive study of a cohort of patients consecutively entered on a community stroke register. SETTING--Community based research project. PATIENTS--A total of 128 patients who had suffered first ever stroke. INTERVENTIONS AND END POINTS--Patients were interviewed by a psychiatrist at 1, 6, and 12 months after stroke. Mood state was assessed by standardised semistructured interview (present state examination) and self report (Beck depression inventory). Intellectual impairment was assessed by mini mental state examination and Frenchay aphasia screening test. In addition, stroke lesions were localised by computed tomography. MAIN RESULTS--Emotionalism was reported by 13 of 89 patients (15%) at one month, 25 of 119 (21%) at six months, and 12 of 112 (11%) at 12 months after stroke. Patients with emotionalism had higher scores on both measures of mood disorder (at 6 months: mean Beck score 10.5 v 6.4; present state examination score 7.2 v 5.1) and more diagnosable psychiatric disorder (at 6 months: 40% v 14%; odds ratio 4.2, 95% confidence interval 1.5 to 11.9). Almost all episodes were provoked by clearly identified and appropriate emotional experiences. Patients with emotionalism also had more intellectual impairment and larger lesions on computed tomography. Lesions in the left frontal and temporal regions were particularly associated with emotionalism: at 6 months 8 of 14 patients (57%) with such lesions had emotionalism compared with 10 of 52 (19%) of those with lesions elsewhere (odds ratio 5.6, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 22). CONCLUSIONS--Emotionalism is common after stroke. It is neither emotionally meaningless and inappropriate, nor is it found mostly in patients with bilateral brain damage. Emotionalism is associated with symptoms of a more general mood disturbance and is found especially in patients with left frontal and temporal lesions.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aho K., Harmsen P., Hatano S., Marquardsen J., Smirnov V. E., Strasser T. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58(1):113–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford J., Sandercock P., Dennis M., Warlow C., Jones L., McPherson K., Vessey M., Fowler G., Molyneux A., Hughes T. A prospective study of acute cerebrovascular disease in the community: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project 1981-86. 1. Methodology, demography and incident cases of first-ever stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988 Nov;51(11):1373–1380. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.11.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovic S. F., Andermann F., Melanson D., Ethier R. E., Feindel W., Gloor P. Hypothalamic hamartomas and ictal laughter: evolution of a characteristic epileptic syndrome and diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1988 May;23(5):429–439. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder L. M. Emotional problems after stroke. Stroke. 1984 Jan-Feb;15(1):174–177. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderby P. M., Wood V. A., Wade D. T., Hewer R. L. The Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test: a short, simple test for aphasia appropriate for non-specialists. Int Rehabil Med. 1987;8(4):166–170. doi: 10.3109/03790798709166209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman E., Mayou R., Hawton K., Ardern M., Smith E. B. Psychiatric disorder in medical in-patients. Q J Med. 1987 May;63(241):405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainotti G. Emotional behavior and hemispheric side of the lesion. Cortex. 1972 Mar;8(1):41–55. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(72)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House A. Depression after stroke. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Jan 10;294(6564):76–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6564.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRONSIDE R. Disorders of laughter due to brain lesions. Brain. 1956 Dec;79(4):589–609. doi: 10.1093/brain/79.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegaard O. F. Diffuse cerebral symptoms in convalescents from cerebral infarction and myocardial infarction. Acta Neurol Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb03152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN J. P. Fits of laughter (sham mirth) in organic cerebral disease. Brain. 1950 Dec;73(4):453–464. doi: 10.1093/brain/73.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. Social origins of depression in old age. Br J Psychiatry. 1982 Aug;141:135–142. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullicino P., Nelson R. F., Kendall B. E., Marshall J. Small deep infarcts diagnosed on computed tomography. Neurology. 1980 Oct;30(10):1090–1096. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.10.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. G., Kubos K. L., Starr L. B., Rao K., Price T. R. Mood disorders in stroke patients. Importance of location of lesion. Brain. 1984 Mar;107(Pt 1):81–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross E. D., Rush A. J. Diagnosis and neuroanatomical correlates of depression in brain-damaged patients. Implications for a neurology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981 Dec;38(12):1344–1354. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780370046005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross E. D., Stewart R. S. Pathological display of affect in patients with depression and right frontal brain damage. An alternative mechanism. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987 Mar;175(3):165–172. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin A. P. Understanding stroke and its rehabilitation. Stroke. 1983 May-Jun;14(3):438–442. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer R. B., Cash J., Herndon R. M. Treatment of emotional lability with low-dosage tricyclic antidepressants. Psychosomatics. 1983 Dec;24(12):1094–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(83)73113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer R. B., Herndon R. M., Rudick R. A. Treatment of pathologic laughing and weeping with amitriptyline. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jun 6;312(23):1480–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506063122303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udaka F., Yamao S., Nagata H., Nakamura S., Kameyama M. Pathologic laughing and crying treated with levodopa. Arch Neurol. 1984 Oct;41(10):1095–1096. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050210093023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing J. K., Mann S. A., Leff J. P., Nixon J. M. The concept of a 'case' in psychiatric population surveys. Psychol Med. 1978 May;8(2):203–217. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing J. K., Nixon J. M., Mann S. A., Leff J. P. Reliability of the PSE (ninth edition) used in a population study. Psychol Med. 1977 Aug;7(3):505–516. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700004487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. K., Santana H. B., Thorpy M. Treatment of "emotional incontinence" with levodopa. Neurology. 1979 Oct;29(10):1435–1436. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.10.1435-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]