Abstract

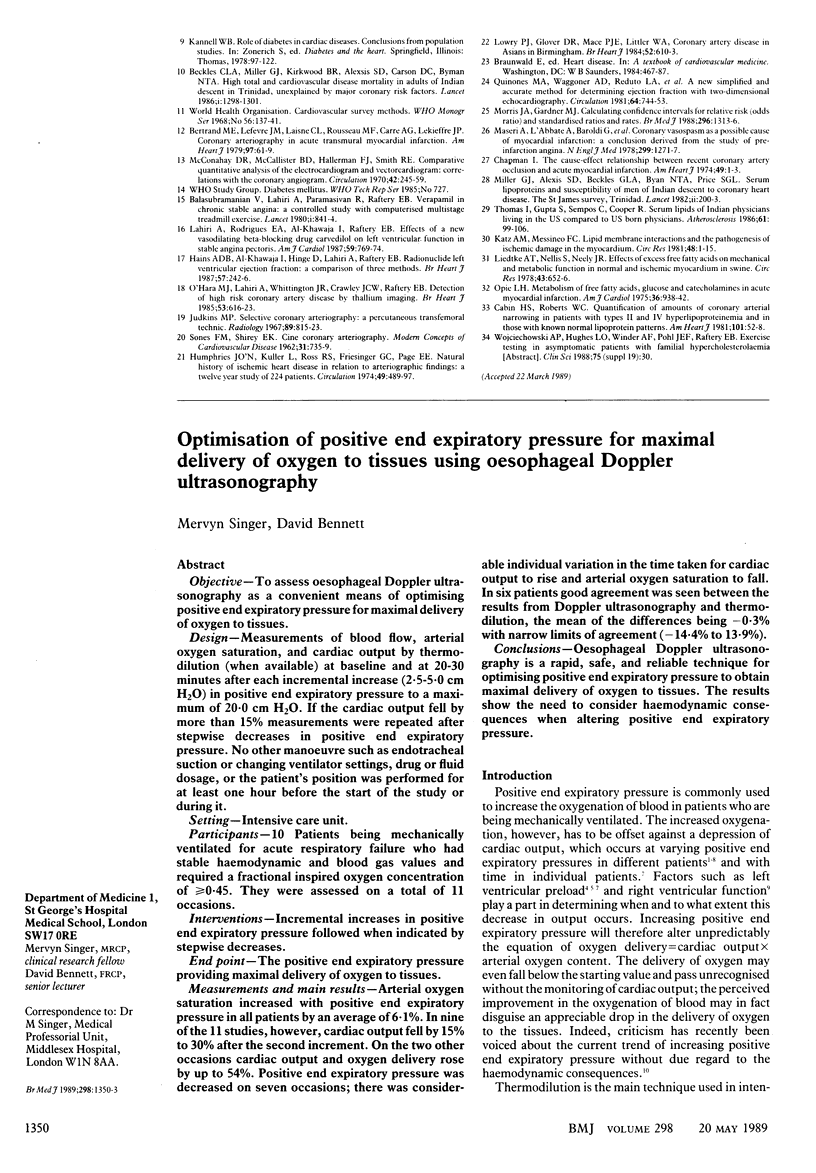

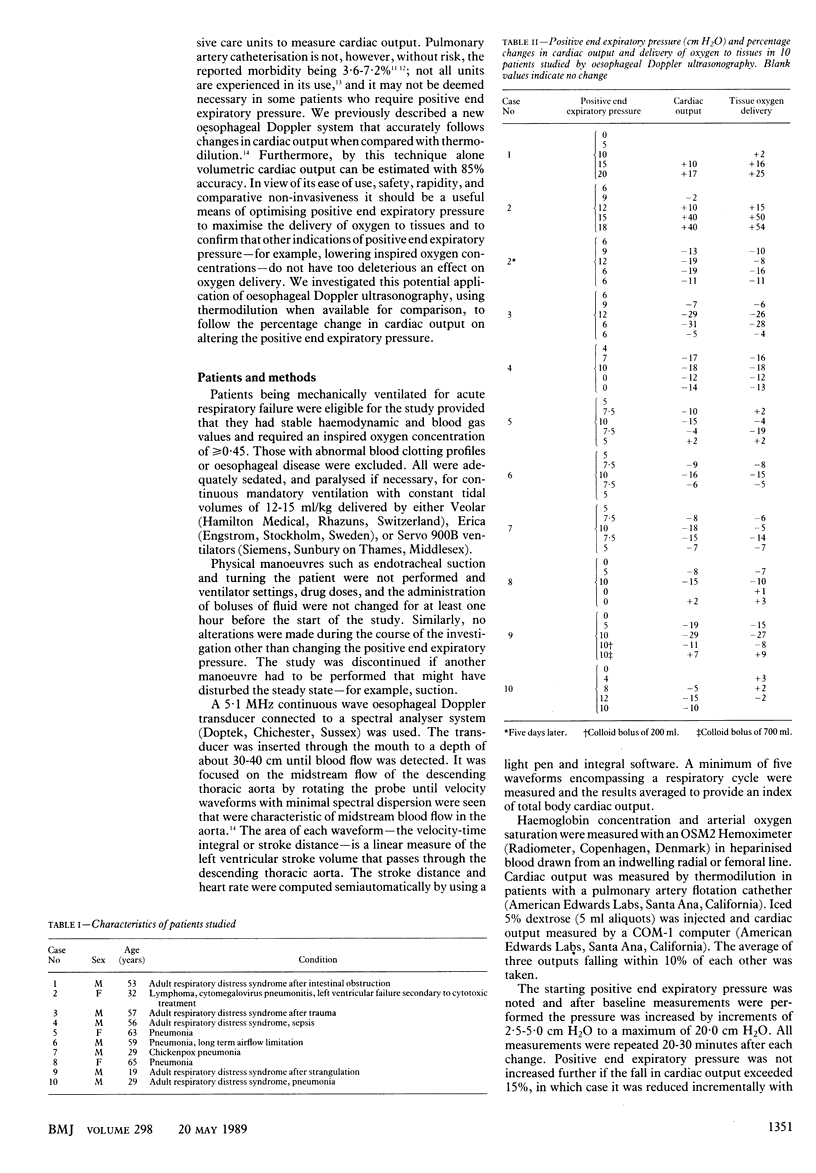

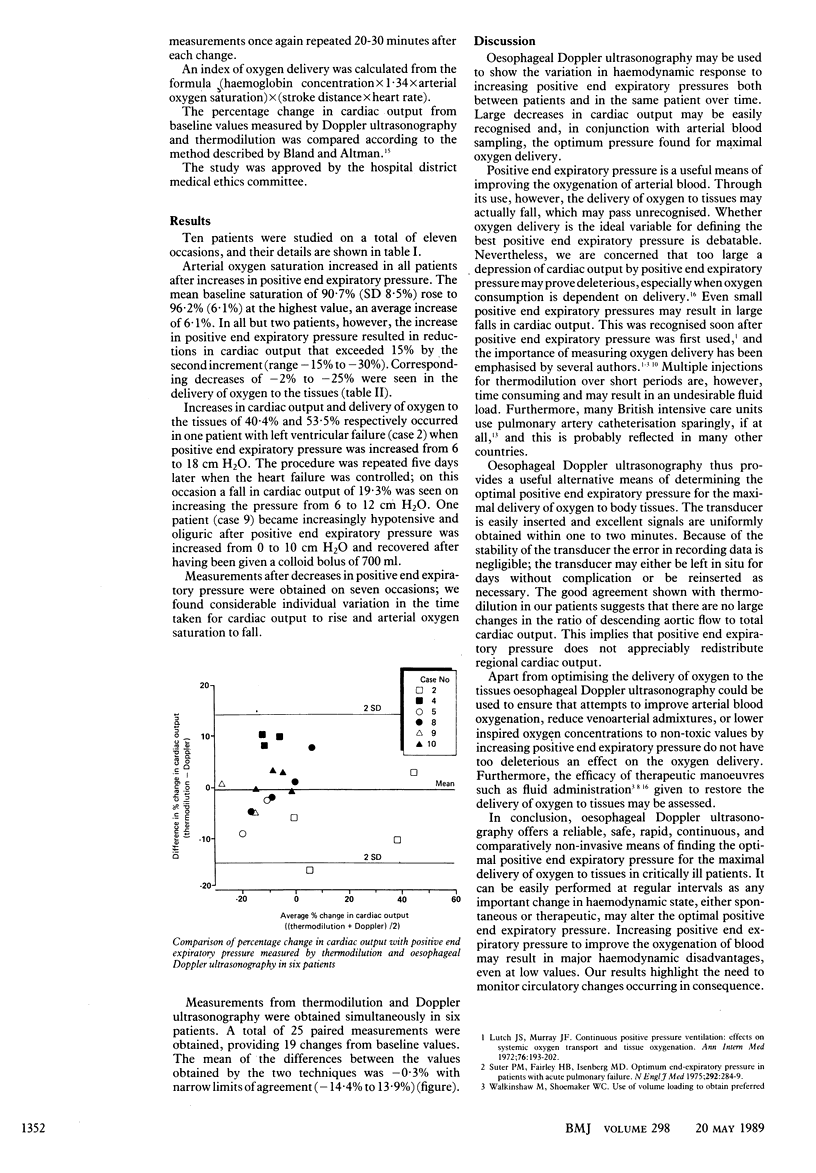

OBJECTIVE--To assess oesophageal Doppler ultrasonography as a convenient means of optimising positive end expiratory pressure for maximal delivery of oxygen to tissues. DESIGN--Measurements of blood flow, arterial oxygen saturation, and cardiac output by thermodilution (when available) at baseline and at 20-30 minutes after each incremental increase (2.5-5.0 cm H2O) in positive and expiratory pressure to a maximum of 20.0 cm H2O. If the cardiac output fell by more than 15% measurements were repeated after stepwise decreases in positive end expiratory pressure. No other manoeuvre such as endotracheal suction or changing ventilator settings, drug or fluid dosage, or the patient's position was performed for at least one hour before the start of the study or during it. SETTING--Intensive care unit. PARTICIPANTS--10 Patients being mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure who had stable haemodynamic and blood gas values and required a fractional inspired oxygen concentration of greater than or equal to 0.45. They were assessed on a total of 11 occasions. INTERVENTIONS--Incremental increases in positive end expiratory pressure followed when indicated by stepwise decreases. END POINT--The positive end expiratory pressure providing maximal delivery of oxygen to tissues. MEASUREMENTS and MAIN RESULTS--Arterial oxygen saturation increased with positive end expiratory pressure in all patients by an average of 6.1%. In nine of the 11 studies, however, cardiac output fell by 15% to 30% after the second increment. On the two other occasions cardiac output and oxygen delivery rose by up to 54%. Positive end expiratory pressure was decreased on seven occasions; there was considerable individual variation in the time taken for cardiac output to rise and arterial oxygen saturation to fall. In six patients good agreement was seen between the results from Doppler ultrasonography and thermodilution, the mean of the differences being -0.3% with narrow limits of agreement (-14.4% to 13.9%). CONCLUSIONS--Oesophageal Doppler ultrasonography is a rapid, safe, and reliable technique for optimising positive end expiratory pressure to obtain maximal delivery of oxygen to tissues. The results show the need to consider haemodynamic consequences when altering positive end expiratory pressure.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin J. E., Driedger A. A., Sibbald W. J. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) does not depress left ventricular function in patients with pulmonary edema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981 Aug;124(2):121–128. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.124.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C. G., Zimmerman G. A., Clemmer T. P. Complications of pulmonary artery catheterization in the care of critically ill patients. A prospective study. Chest. 1979 Dec;76(6):647–652. doi: 10.1378/chest.76.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote G. A., Schabel S. I., Hodges M. Pulmonary complications of the flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med. 1974 Apr 25;290(17):927–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197404252901702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace M. P., Greenbaum D. M. Cardiac performance in response to PEEP in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1982 Jun;10(6):358–360. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin F., Farcot J. C., Boisante L., Curien N., Margairaz A., Bourdarias J. P. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med. 1981 Feb 12;304(7):387–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102123040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutch J. S., Murray J. F. Continuous positive-pressure ventilation: effects on systemic oxygen transport and tissue oxygenation. Ann Intern Med. 1972 Feb;76(2):193–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-2-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L. D., Houtchens B. A., Westenskow D. R. Oxygen consumption and optimum PEEP in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 1982 Dec;10(12):857–862. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt R. M., Oppenheimer L., Sutherland J. B., Wood L. D. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on left ventricular mechanics in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 1981 Oct;55(4):409–415. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman D. S., Biondi J. W., Matthay R. A., Barash P. G., Zaret B. L., Soufer R. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricular performance. Importance of baseline right ventricular function. Am J Med. 1988 Jan;84(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M., Bennett E. D. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring in the United Kingdom. Enough or too little? Chest. 1989 Mar;95(3):623–626. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter P. M., Fairley B., Isenberg M. D. Optimum end-expiratory airway pressure in patients with acute pulmonary failure. N Engl J Med. 1975 Feb 6;292(6):284–289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502062920604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkinshaw M., Shoemaker W. C. Use of volume loading to obtain preferred levels of PEEP. A preliminary study. Crit Care Med. 1980 Feb;8(2):81–86. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]