Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori testing has been suggested as an alternative to endoscopy for young patients with dyspepsia. Secondary care studies have suggested that demand for endoscopy among this group could be reduced by up to 74%. However, the effect of H. pylori testing in the primary care setting, where the majority of dyspepsia is managed, is unclear.

Aim

To determine the effects of providing a H. pylori serology service for GPs upon demand for open access endoscopy.

Design of study

A prospective randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Forty-seven general practices in Gloucestershire.

Method

General practices were stratified by endoscopy referral rate and randomised into two groups. The intervention group was provided with access to H. pylori serology testing and encouraged to use it in place of endoscopy for patients aged under 55 years with dyspepsia. Endpoints were referral for endoscopy and serology use.

Results

There was a significant reduction in referrals for endoscopy in the intervention group compared to the control group: 18.8% (95% confidence interval = 5.0 to 30.6%; P = 0.009).

Conclusions

Providing GPs with H. pylori serology testing reduced demand for open access endoscopy, but by less than previous studies had predicted.

Keywords: dyspepsia, endoscopy, Helicobacter pylori, serology

INTRODUCTION

Dyspepsia is a common clinical problem, which accounts for considerable health service usage. Up to 3% of general practice consultations in England relate to dyspepsia,1 and the total cost of managing dyspepsia in the NHS exceeds £1 billion per annum.2 Consequently there has been much interest in streamlining dyspepsia management and a number of strategies have been suggested, including ‘test and treat’, which utilises Helicobacter pylori testing in place of endoscopy for young patients with dyspepsia.3,4 Under this strategy, eradication therapy is given to patients who test positive for H. pylori and symptomatic therapy is given to patients who test negative. Only patients with alarm features or those who fail to respond to initial therapy need to be referred for endoscopy. It is widely believed that this approach will significantly reduce the demand for endoscopy and the strategy has recently been incorporated into the NICE dyspepsia management guidelines.5

Evidence to support the use of H. pylori testing to reduce demand for endoscopy arises from a number of studies undertaken in secondary care,6,7,8 which have found that ‘test and treat’ provides comparable levels of patient satisfaction to endoscopy and can reduce demand for endoscopy among young patients with dyspepsia by as much as 74%. However, there are well recognised problems with extrapolating secondary care data into primary care,9 and the extent to which the result of these studies can be applied to primary care, where the majority of dyspepsia is managed, is unclear. To date, the four randomised controlled trials, which have attempted to examine the impact of a primary care based ‘test and treat’ strategy, have demonstrated similar reductions in endoscopy demand to the secondary care studies.10–13 However, all four studies compared the test and treat strategy with an ‘endoscope all’ policy, which is unlikely to be representative of everyday practice. In addition, two of these studies,10,13 used near-patient testing to assess H. pylori status, which has been shown to be potentially unreliable.14 Duggan's study, unlike the secondary care studies, found greater patient satisfaction among patients receiving endoscopy compared with those in the ‘test and treat’ group.13

How this fits in

The NICE guidelines for managing adults with dyspepsia have adopted a ‘test and treat’ strategy based on studies performed in secondary care, which have suggested that ‘test and treat’ produces similar results to early endoscopy, while reducing demand for endoscopy by up to 70%. The result of this study, which examined the impact of introducing a primary care based ‘test and treat’ strategy, suggests that the reduction in endoscopy demand may be significantly less than anticipated.

The aim of our study was therefore to use a pragmatic randomised controlled design to examine the effect of a serology based H. Pylori test and treat strategy on demand for endoscopy in an everyday primary care setting.

METHOD

Setting

The study was carried out in West Gloucestershire, which has a population of 320 000 of mixed urban and rural types served by a district general hospital and 48 GP practices. Open access endoscopy has been available in West Gloucestershire for more than 20 years15 and is currently provided in three separate units: the Gloucestershire Royal Hospital and two community hospitals. Practice list size and age distribution was obtained from the local health authority database and was assumed constant throughout the study period.

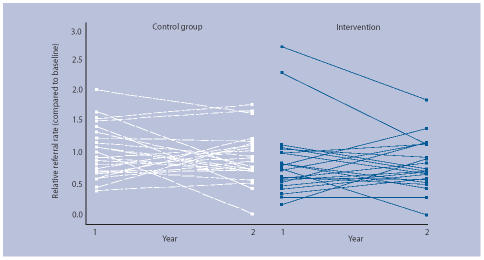

Study design and allocation methods

The study design was a randomised controlled trial (Figure 1). Participating practices were stratified according to fundholding status and the practices in each of these groups were then ranked according to their endoscopy referral rate in the year prior to the study (1996). The two groups were then divided about the midpoint, generating four groups: fundholders with high and low referral rates and non-fundholders with high and low referral rates. Each practice was assigned a random five-digit number and the practices were ranked by this number within their group. The upper half of each group was assigned to the intervention arm and the lower half to the control arm.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Intervention

The intervention was chosen to closely mirror every day practice. Practices randomised to the intervention arm were given access to H. pylori serology testing. They were sent written information promoting the use of the serology service in place of endoscopy for patients under the age of 55 years suffering from dyspepsia without alarm symptoms and were issued with a summary of the Maastricht consensus statement on the management of H. pylori.3 We advocated H. pylori eradication with triple therapy in patients with a positive result and symptomatic therapy for the others. A computer-generated summary of these recommendations was included with each H. pylori serology result. The GPs remained free to refer for open access endoscopy as they felt necessary. An age cut off of 55 years was chosen because local data has shown that upper gastrointestinal malignancy is rare in patients below this age if there are no alarm symptoms.16

Serum was tested by the Public Health Laboratory using Meridian Diagnostics Premier H. pylori EIA (Launch Diagnostics Ltd, Longfield, UK), which had previously been validated among open access endoscopy patients attending our unit and shown to have a sensitivity of 97%, specificity of 85%, and positive predictive value in an endoscopy population of 81%.17 Practices in the control arm were issued with a summary of the Maastricht consensus statement on the management of H. pylori,3 accompanied with a letter highlighting the lack of evidence to support the recommendation for eradication in functional dyspepsia and reflux disease. Control practices were encouraged to continue their usual practice and were not provided with access to the serology service. Reminders about the study were sent to participating GPs at 6 and 12 months.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the number of referrals for open access endoscopy. All requests for open access endoscopy sent to the three endoscopy units were collated during the calendar year 1996 (baseline year) and to the end of the study (31 March 1999). Secondary endpoints were the number of serology requests received and referrals for C14 urea breath testing.

Statistical analysis

The baseline data was compared to ensure that no major differences existed between the intervention and control groups. A random effects Poisson regression model was fitted to the data to provide an estimate of the reduction in endoscopy referrals in the intervention group together with its standard error. The number of referrals by each practice was used as the dependent variable. Intervention, year, and fundholding status were binary predictor variables. Any differences in the baseline referral rate were adjusted by including this as a covariate in the model.

The cluster randomised design was incorporated into the analysis by the addition of a between practice variance component.18 The model was normalised for practice size to allow direct estimation of the endoscopy referral rate. Interactions between the fixed components of the model were explored. Analysis was performed using Stata 8.1 (Stata Statistical Software, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Forty-seven of the 48 GP practices invited agreed to participate in the study. One of the participating practices in the intervention arm was excluded from the analysis because the practice was not able to provide the number of registered patients aged under 55 years. Baseline characteristics after randomisation were well matched (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline comparison: characteristics.

| Control | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of practices | 24 | 22 |

| Number of patients | ||

| Total | l111 216 | 104 016 |

| Per practice (median) | 4277 | 4573 |

| Range | 1779–10 227 | 1618–10 983 |

| Endoscopy requests | ||

| Total | 415 | 414 |

| Ratea per 1000 patients (95% CI) | 3.55 (2.98 to 4.24) | 3.88 (3.08 to 4.90) |

| Per practice (median) | 18 | 17 |

| Range | 2–43 | 3–39 |

Rate estimated allowing for the cluster randomised design.

Serology

Among the intervention group, 340 tests were performed in year 1 and 491 tests year 2. Ninety-six (28.2%) and 141 (28.7%) of the tests were positive in the 2 years respectively.

Endoscopy referrals

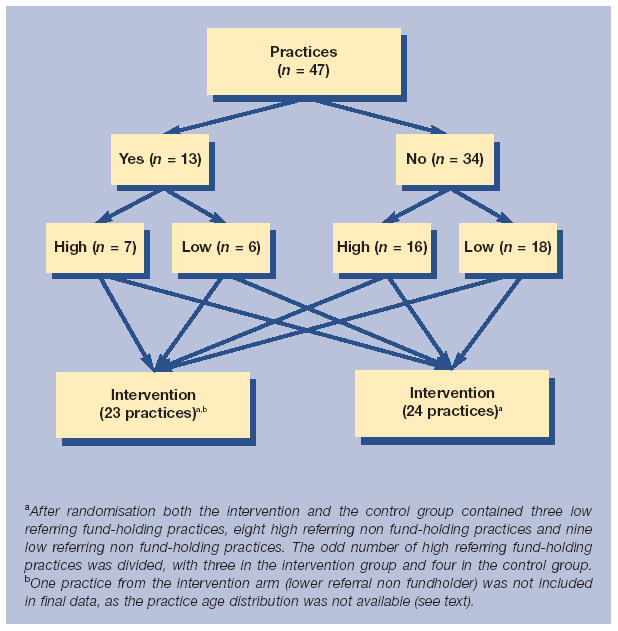

The number of endoscopy referrals fell in both groups during the study period, but fell by a greater amount in the intervention group compared to the control group (Table 2). During the 2 year study period, 626 referrals were received from the intervention group compared to 771 from the control group, a crude reduction of 18.8%. Figure 2 shows the relative referral rate in the two groups. A relative rate below 1 indicates a decrease from the baseline in endoscopy requests. The random effects model (Table 3) confirms that there was a significant reduction in the endoscopy referral rate in the group with access to serology compared to the control group (18.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.0% to 30.6%; P = 0.009)).

Table 2.

Endoscopy referrals.

| Control | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (1996) | ||

| Endoscopy requests | 415 | 414 |

| Year 1 (01/4/97–31/3/98) | ||

| Endoscopy requests (change since baseline) | 398 (−4.1%) | 301 (−27.3%) |

| Year 2 (01/4/98–31/3/99) | ||

| Endoscopy requests (change since baseline) | 373 (−10.1%) | 325 (−21.5%) |

Figure 2.

Relative endoscopy referral rates.

Table 3.

Random effects Poisson regression model.

| Predictor | Estimated referral ratio | Standard error | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 0.812 | 0.065 | 0.694 to 0.950 | 0.009 |

| Fundholder | 1.009 | 0.087 | 0.852 to 1.195 | 0.919 |

| Year | 0.999 | 0.053 | 0.899 to 1.109 | 0.979 |

| Baseline rate (per 1 per 1000) | 1.165 | 0.021 | 1.125 to 1.206 | <0.001 |

| Sigma_u | 0.185 | 0.050 | 0.109 to 0.313 | 0.002 |

Breath test referrals

Breath test referrals were not affected with 73 versus 55, 61 versus 56 and 49 versus 46 tests being requested in the control and intervention groups during year 0, 1 and 2, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

The findings of our study support the fact that a serology based ‘test and treat’ strategy for patients with dyspepsia can reduce demand for endoscopy; however, the reduction of 18.8% that we have demonstrated is considerably less than predicted by previous studies, which have shown reductions of up to 74%.6,8

Strength and limitations of the study

The main strength of our study is that the intervention and control groups were chosen to closely match ‘real world’ community dyspepsia management. Importantly, in contrast to the majority of published trials where the ‘test and treat’ strategy has been compared with a control group in which all patients are endoscoped, not all dyspeptic patients in our control group were endoscoped. We believe that our control group more closely reflects current primary care practice and this is supported by our baseline endoscopy referral rate of 0.6% per head of population per annum, which is in line with rates of 0.5–1% reported elsewhere.19,20

The fall in endoscopy referral in our control group, especially in year 2, was unexpected and partly accounts for the small differences between the two groups. This change would not have been apparent in a study using historical controls. It is unlikely that the changes in the control group reflect contamination bias from GPs in the intervention group, as we attempted to minimise this possibility by randomising at practice level and denying the control group access to serology. It seems more likely that the reductions seen in the control group relate to a general awareness of the low yield from endoscopy in young patients with dyspepsia.

The major limitation of our study is that it was not designed to examine patient outcomes or satisfaction with serology testing. Consequently, we cannot comment on this important aspect of patient management. However, it is possible to speculate that one of the reasons for the small reduction in endoscopy referrals seen in our study, particularly in year 2, is that patients were not satisfied after having H. pylori serology testing and were subsequently referred for endoscopy. This suggestion would be supported by the results of Duggan's study,13 which examined community H. pylori testing and found increased satisfaction among patients undergoing endoscopy. This is in contrast to other studies that have found equal satisfaction and resolution of symptoms with the two strategies when H. pylori testing has been performed as part of an assessment in secondary care.6,7 The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but it is possible that assessment in secondary care may provide patients with greater reassurance.

Finally, much has been written about the problems of dyspepsia guideline implementation21 and our intervention was chosen to be a pragmatic ‘real world’ one, where the initial information was conveyed in writing and a reminder of our recommendations was included on every serology report. It is possible that a greater effect could have been achieved by more rigorous implementation of the intervention. However, the smaller reduction in endoscopy demand in our study cannot be simply explained by poor uptake of serology by the intervention GPs, as serology tests outnumbered endoscopy referrals throughout the study.

Comparison with existing literature

There are a number of factors that may explain the disparity between our observed findings and the reduction in endoscopy predicted by earlier studies. Our use of a non-historic control group that did not all receive endoscopy and the fact that our H. pylori testing was carried out in the community has been discussed. In addition, previous studies only included H. pylori positive patients, whereas our study included all dyspeptic patients, with an overall H. pylori infection rate of 28%. Therefore, the patients in our study are likely to have a lower incidence of ulcers and proportionately more non ulcer dyspepsia, which may be less likely to respond to simple symptomatic therapy. The possibility of a lower impact from a test and treat strategy among H. pylori negative patients is supported by Heaney's study, which found only a 42% reduction in endoscopy using a ‘test and treat’ strategy in H. pylori negative patients compared with a 73% reduction in H. pylori positive patients.22

Implications for future dyspepsia management strategies

The relatively modest reduction in endoscopy demand found in our study suggests an important difference between managing dyspepsia in primary and secondary care and raises the possibility that the widespread adoption of a ‘test and treat’ strategy, as advocated by the NICE dyspepsia guidelines, may have less impact on endoscopy demand than currently anticipated. Further work is clearly needed to explore additional strategies to control endoscopy demand and these should focus on the differences between managing dyspepsia in the primary and secondary care setting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bodger K, Eastwood PG, Manning SI, et al. Dyspepsia workload in urban general practice and implications of the British Society of Gastroenterology dyspepsia guidelines (1996) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:413–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OHE Compendium of Health Statistics. 8th edition. London: Office of Health Economics; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht consensus report. Gut. 1997;41:8–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agresus L, et al. AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 1999;114:582–595. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NICE Clinical Guideline no 17. Dyspepsia: management of adults in primary care. 2004 Aug; www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=CG017fullguideline (accessed 7 Apr 2006)

- 6.Heaney A, Collins JSA, Watson RGP, et al. A prospective randomised trial of a test and treat policy versus endoscopy based management in young Helicobacter pylori positive patients with ulcer like dyspepsia, referred to a hospital clinic. Gut. 1999;45:186–190. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McColl KEL, Murray LS, Gillen D, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopy with testing for Helicobacter pylori compared with non-invasive H pylori testing alone in the management of dyspepsia. BMJ. 2002;324:999–1002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7344.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slade PE, Davidson AR, Steel A, et al. Reducing the endoscopic workload: does serological testing for Helicobacter pylori help? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:857–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson S, Delaney BC, Roalfe A, et al. Randomised controlled trials in primary care: case study. BMJ. 2000;321:24–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones R, Tait C, Sladen G, et al. A trial of test and treat strategy for helicobacter positive patients in general practice. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arents NL, Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, et al. Approach to treatment of dyspepsia in primary care: a randomised trial comparing test and treat with prompt endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1606–1612. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassen AT, Pedersen FM, Bytzer P, et al. H. pylori test-and-eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: a randomised. Lancet. 2000;356:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duggan A, Elliot C, Tolley, et al. Randomised controlled trial of four dyspepsia management strategies in primary care with 12 months follow up. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(4 supp 2):A2388. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaira D, Vakil N. Blood, urine, stool, breath, money, and Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:287–289. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gear MWL, Wilkinson SP. Open access upper alimentary endoscopy. Br J Hosp Med. 1989;41:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christie J, Shepherd NA, Codling BW, et al. Gastric cancer below the age of 55: implications for screening patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia. Gut. 1997;41:513–517. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNulty CA, Nair P, Watson BE, et al. A comparison of six commercial kits for Helicobacter pylori detection. Commun Dis Public Health. 1999;2:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nixon RM, Thompson SG. Baseline adjustments for binary data in repeated cross-sectional cluster randomised trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22(17):2673–2692. doi: 10.1002/sim.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axon AT, Botrill PM, Campbell D. Results of a questionnaire concerning the staffing and administration of endoscopy in England and Wales. Gut. 1987;28:1527–1530. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.11.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asante M, Bland J, Mendall M, et al. Determinants of prescribing costs for ulcer-healing drugs and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in general practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:589–593. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199807000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patrick H, Bolton P, Brickenden K. Problems with implementing and evaluating the effect of locally developed guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. J Clin Effectiveness. 1998;3:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaney A, Collins JS, Tham TC, et al. A prospective study of the management of the young Helicobacter pylori negative dyspeptic patient - can gastroscopies be saved in clinical practice? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:953–956. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]