Abstract

Background

Dupuytren's contracture or disease (DD) is a fibro-proliferative disease of the hand that results in the development of scar-like, collagen-rich disease cords within specific palmar fascia bands. Although the molecular pathology of DD is unknown, recent evidence suggests that β-catenin may play a role. In this study, collagen matrix cultures of primary disease fibroblasts show enhanced contraction and isometric tension-dependent changes in β-catenin and fibronectin levels.

Methods

Western blots of β-catenin and fibronectin levels were determined for control and disease primary cell cultures grown within stressed- and attached-collagen matrices. Collagen contraction was quantified, and immunocytochemistry analysis of filamentous actin performed.

Results

Disease cells exhibited enhanced collagen contraction activity compared to control cells. Alterations in isometric tension of collagen matrices triggered dramatic changes in β-catenin and fibronectin levels, including a transient increase in β-catenin levels within disease cells, while fibronectin levels steadily decreased to levels below those seen in normal cell cultures. In contrast, both fibronectin and β-catenin levels increased in attached collagen-matrix cultures of disease cells, while control cultures showed only increases in fibronectin levels. Immunocytochemistry analysis also revealed extensive filamentous actin networks in disease cells, and enhanced attachment and spreading of disease cell in collagen matrices.

Conclusion

Three-dimensional collagen matrix cultures of primary disease cell lines are more contractile and express a more extensive filamentous actin network than patient-matched control cultures. The elevated levels of β-catenin and Fn seen in collagen matrix cultures of disease fibroblasts can be regulated by changes in isometric tension.

Background

Dupuytren's contracture or disease (DD) is a benign, but debilitating fibro-proliferative disease of the palmar fascia [1] that causes permanent flexion of the affected fingers [2]. Clinically, DD progresses through distinct stages with the earliest stage of the disease characterized by the appearance of small nodules of hyperproliferative cells that give rise to scar-like, collagen-rich disease cords (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Classical presentation of Dupuytren's contracture. The most commonly affected digits are the ulnar digits (ring and small fingers). Surgery is indicated when joint contracture exceeds 30°, or when nodules are painful and interfere with hand function.

In spite of numerous studies over the years, the etiology of this disease remains obscure. However, DD does display several features of a cancer, including high rates of recurrence following surgery, distinct chromosomal abnormalities [3-7], and increased total and cancer mortality rates among men with established disease [8,9]. This notion is further supported by studies from our labs and others that show aberrant expression of β-catenin, a key cell signalling molecule frequently mutated in human cancers [10,11], in DD [12,13], including several related fibromatoses [14-18]. Additional studies from our laboratories also suggest that β-catenin may play an important role in cutaneous wound healing [19].

β-catenin was first identified as a component of cell-cell adhesion structures (adherens junctions) that physically couples cadherins to the cytoskeleton via α-catenin (Fig. 2) [20-22]. It is also a key signalling factor within the canonical Wnt pathway [10], which is involved in growth and development of numerous cell types [23]. In the canonical Wnt pathway (Wnt/β-catenin), these secreted ligands bind to receptor complexes, consisting of a Frizzled (Fz) receptor and a low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) [24-27]. Upon Wnt stimulation glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) catalyzed phosphorylation of β-catenin is inhibited resulting in an increase in the 'free' (uncomplexed to cadherin) cytosolic levels of β-catenin. This in turn leads to its subsequent accumulation within the nucleus, where it binds to members of the Tcf/Lef (T-cell factor-lymphoid enhancer factor) transcription factor family [28,29] to regulate gene expression [30-34].

Figure 2.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. β-catenin is a component of cell-cell adhesion structures (adherens junctions) [20-22] and a key signaling factor in the Wnt pathway [10]. As shown here canonical Wnt signalling (Wnt/β-catenin) is defined by its inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) catalyzed phosphorylation of β-catenin. Several factors, including Cer (cerebrus), WIF-1 (wnt-interacting protein), and sFRPs (secreted frizzled related proteins) and dickkopf-1 (Dkk) are known to antagonize Wnt signalling [63-69]. However, upon Wnt stimulation several Fz-LRP downstream signalling components, including the phosphoprotein dishevelled (Dvl) [70-72], GBP/Frat1 (GSK-3β Binding Protein) [73] and casein kinase I (CKIε) [74,75], somehow co-operate to inhibit GSK-3β. This ultimately this leads to an increase in the cytosolic 'free' levels of β-catenin (uncomplexed to cadherin), and its accumulation within the nucleus where it binds to members of the Tcf/Lef (T-cell factor-lymphoid enhancer factor) transcription factor family to activate gene transcription in a cell-context dependent manner [28-34]. In the absence of Wnt signalling, Axin/conductin [76,77] in co-operation with the product of the tumour suppressor gene adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [78,79] facilitate GSK-3β mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin on N-terminal serine and threonine residues [80]. This hyper-phosphorylated form of β-catenin then binds to the F-box protein β TrCP, which targets β-catenin for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway [81-84].

(CKIε) [74,75], somehow co-operate to inhibit GSK-3β. This ultimately this leads to an increase in the cytosolic 'free' levels of β-catenin (uncomplexed to cadherin), and its accumulation within the nucleus where it binds to members of the Tcf/Lef (T-cell factor-lymphoid enhancer factor) transcription factor family to activate gene transcription in a cell-context dependent manner [28-34]. In the absence of Wnt signalling, Axin/conductin [76,77] in co-operation with the product of the tumour suppressor gene adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [78,79] facilitate GSK-3β mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin on N-terminal serine and threonine residues [80]. This hyper-phosphorylated form of β-catenin then binds to the F-box protein β TrCP, which targets β-catenin for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway [81-84].

Alterations in the extracellular matrix (ECM) are another important clinical feature of DD. Disease cords are largely composed of collagen type I, and have elevated levels of collagen type III compared to normal palmar fascia tissue [35-38]. Fibronectin (Fn), a well known extracellular glycoprotein that plays a vital role in numerous cell functions, including adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation [39], is also prominently expressed in DD lesions, most notably within extracellular plaques, termed fibronexus, that are closely associated with DD myofibroblasts [40]. To-date, various Fn isoforms and their post-translational modified forms (ED-A, ED-B, oncofetal Fn), which are typically associated with tissues undergoing extensive proliferation and remodelling, have been documented in DD [41,42]. Recent studies in our lab have also documented aberrant expression of oncofetal Fn in primary cultures of DD lesions compared to patient-matched control fascia derived primary cultures (Varallo et al. unpublished). Although the importance of oncofetal production by DD cells are not clear the ability of these cells to actively modify the composition of the ECM appears to facilitate collagen contraction in vitro (Fig. 3) [43]. Nevertheless, the exact roles that these Fn isoforms, or indeed other ECM components play in the pathogenesis of DD is not known.

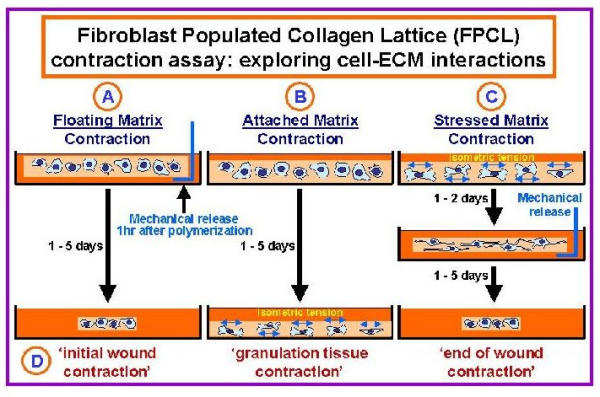

Figure 3.

Fibroblast Populated Collagen Lattice contraction assays. Fibroblast populated collagen lattice (FPCL) cultures have been used by many researchers to model cell-ECM interactions associated with wound contraction and DD [58]. As illustrated here three types of FPCLs have been used by investigators, including (A) Floating- (B) Attached- and (C) Stressed-matrices. Floating-matrices are mechanically released from the sides of the dishes immediately after gel polymerization (1 hour). In contrast, isometric tension is allowed to build up in cells placed in attached- and stressed-matrix cultures. In attached-matrices the contractile forces exerted by cells encounter mechanical resistance, which is thought to mimic 'granulation tissue contraction' (D, in vivo-like phenotypes), while cells seeded in stressed-matrices develop isometric tension during an initial attached period (1 to 2 days) that dissipates when the lattices are mechanically released.

In light of the potential role of β-catenin in the pathogenesis of DD [13] and the importance of ECM in DD, we examined both β-catenin and Fn levels in relation to mechanical stress, using Fibroblast Populated Collagen Lattice (FPCL) cultures of patient-matched normal and disease primary cell lines. Recent studies from our labs have shown that FPCL cultures of primary disease cell lines have significantly elevated levels of β-catenin compared to control FPCL cultures [13], suggesting that tension and the surrounding ECM may be important factors regulating β-catenin expression in DD. This is an intriguing possibility since tension and the ECM are important clinical factors in DD [36,37,44-46]. Experiments described here examined β-catenin and Fn levels as a function of changes in isometric tension. The phenotypic differences between control and disease cell cultures reported here suggest that the FPCL culture system may be a good in vitro model to explore disease-specific changes in cell function.

Methods

Clinical specimens and primary cultures

Surgical specimen were collected in strict compliance with the Institute's chief pathologist and the ethics committee for research involving human subjects at UWO. Briefly, diseased fascia (cords) and adjacent, uninvolved (control) palmar fascia tissue was collected and divided in two portions for protein analysis (immediately stored -80°C) and primary cell cultures. For explant cultures, fascia specimen were finely minced and placed in starter media consisting of α-MEM (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, Grand Island, NY) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) and antibiotics (Penicillin G + streptomycin sulfate, Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, Grand Island, NY). Established primary cell culture lines were maintained in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Culture flasks were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chambers with 5% CO2. Medium was changed every 4–5 days and the cells were sub-cultured using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, Grand Island, NY) when confluent.

FPCL contraction assay

Collagen contraction assays were carried out using disease (D) and control (C) primary cell cultures established from lesional and adjacent normal (uninvolved) fascia from the same patient (i.e. patient-matched), respectively. Primary cultures (passages 4–6) were grown as three dimensional Fibroblast Populated Collagen Lattices, or FPCL (Fig. 3). Collagen lattices were prepared by mixing cells with a neutralized solution of collagen type I (8 parts Vitrogen100 collagen type I, 2.9 mg/ml, Collagen Corp, Santa Clara, CA, USA + 1 part 10x α-MEM + 1 part HEPES buffer, pH 9). Final collagen and cell concentrations for the FPCL were 2.0 mg/ml and 2 × 105 cells/ml of matrix, respectively. The cell-collagen mixture was then aliquoted into 24 well culture dishes (0.5 ml/well) that were pre-treated with a PBS + 2% BSA solution. Once polymerized (1 hr, 37°C) α-MEM + 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) was added atop FPCLs in each well. After 2 days of incubation, the attached FPCL were mechanically released from the sides of the culture plates. Digital images of the contracting FPCL were captured at various time points over 5 days using a conventional flatbed scanner. Collagen lattice areas were then measured using NIH imaging software.

Western blots

FPCL were harvested at various post-mechanical released time points, homogenized and protein extracts prepared using a modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml of aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF) (Sigma, St. Louis MO, USA). The resulting FPCL homogenate was then centrifuged (15 min, 4°C 12,000 × g) to remove cell debris. Cells numbers were quantified using an in vitro toxicology assay kit based on lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (Sigma, St. Louis MO, USA), according to the manufacturers instructions. Equivalent cellular protein levels were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene difuoride (PVDF) membranes (BioRad, Hercules CA, USA). Membranes were blocked overnight (4°C) with a PBS solution containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and 5% fat free skim milk, washed 2x in PBST, and then sequentially probed with anti-β-catenin (1:750, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA), anti-Fn (clone IST-4, 1:500, Sigma, St. Louis MO, USA), and anti-heat shock protein 47 (Hsp47) antibodies (1:500, StressGen, Victoria BC, Canada). After a brief series of PBS washes membranes were then incubated with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated 2° antibodies (1:5000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove PA, USA) for 45 min. at room temperature (RT). Antibody-specific bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents and Kodak XLS film (Rochester NY, USA). Antibody-specific bands for β-catenin, fibronectin and Hsp47 were quantified using NIH Imaging software. Both β-catenin and fibronectin levels were normalized to control Hsp47 levels by calculating the appropriate ratio values (i.e. β-catenin:Hsp47, and Fn:Hsp47). The plotted bar graph values therefore represent the mean ratio intensity ± SEM per time point. For attached-matrix experiments, harvested FPCLs were treated as described above except that they were not mechanically released from the sides of the dishes throughout the 5 day incubation period.

Immunocytochemistry analysis of FPCL cultures

Individual lattices were briefly washed in PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Ft. Washington PA, USA) for 1 hr at room temperature (RT), permeabilized in PBS + 0.5%Tween (PBST) for 15 min at RT, and then blocked overnight at 4°C with PBS + 2% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove PA, USA). Lattices were then incubated with the nucleic acid stain DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride, Molecular Probes, Eugene ON, USA) for 20 min at RT, and then stained for 20 min at RT with phalloidin-Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene ON, USA). The lattices were then briefly washed in PBS and mounted onto glass slides using aqueous DAKO faramount mounting media (DAKO Diagnostics, Carpinteria CA, USA). Digital images were acquired on a Nikon eclipse TE-200 inverted fluorescent microscope using a Photometrics series 300 cooled CCD camera, and deconvolved using softWoRx (v 2.5) software (Applied Precision Inc., Issaquah WA, USA).

Results and Discussion

FPCL contraction

FPCL cultures of DD primary cell lines not only provides a functional assay to quantify cell-mediated collagen contraction events, but also an 'in vivo-like' environment (i.e. three-dimensional collagen-rich matrix environment) to study cell-matrix interactions. Primary cell lines established from patient-matched disease fascia and adjacent uninvolved normal fascia tissue (n = 5 patient) were cultured as 'stressed-matrices' (Fig. 3). Following 2 days of attached-culture FPCLs were mechanically released from the sides of the culture dishes and digital images of the contracting gels collected over a 5 day incubation period. As shown in Fig. 4, area measurements of the contracting FPCL for all five patient-matched primary cell lines show that the disease cell cultures contracted collagen significantly more between 30 min. and 5 days compared to control FPCLs (*P < 0.05, student T-test). The differences in contraction rates is consistent with a number of earlier FPCL studies that demonstrated enhanced contractile activity of fibroblasts derived from DD lesions [47-49]. However, these studies utilized carpal tunnel fibroblasts as control cells and often used a floating-matrix rather than stressed-matrix contraction model to quantify cell-mediated collagen contraction, thus making it difficult to directly compare results.

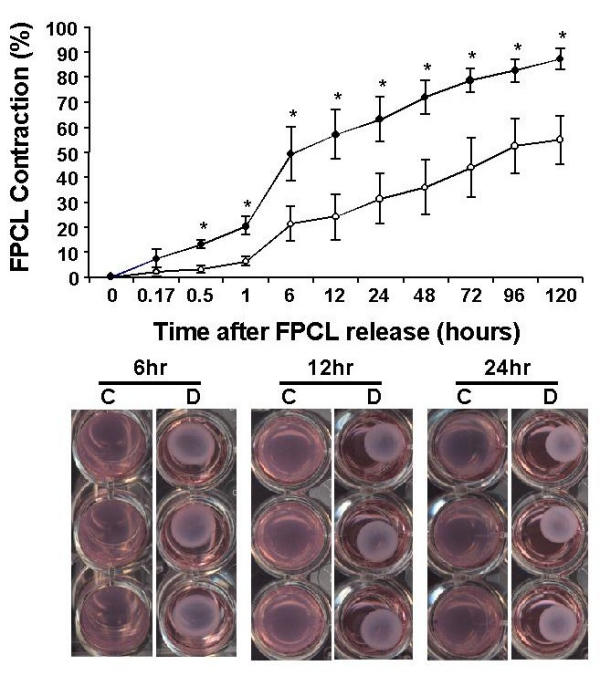

Figure 4.

Stressed-matrix contraction of primary DD cultures. The graph displays the percent FPCL contraction of five patient normal/control (C) and diseased (D) matched primary cell lines over an incubation period of 5 days. Data plotted represents the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) values of all five patient-matched primary cell lines. Representative images of contracting FPCLs are shown in the lower panel for the indicated time points after mechanical release of the FPCLs. Digital images of the contracting FPCLs were analysed using NIH Imaging software to determine lattice areas for the indicated time points. Statistical pair-wise analysis was performed using a student t-test analysis. *Statistical significance (P < 0.05) between disease and control FPCLs.

Stressed-collagen lattices stained with phalloidin-Alexa 488, a fluorescent probe that binds filamentous actin, revealed more prominent stress fiber networks in the disease FPCLs compared to control FPCLs (Fig. 5), suggesting that the disease cells may be more inherently responsive to factors that promote collagen contraction. Although the exact nature of the cell signalling networks responsible for the enhanced contractile activity of the disease cells is unclear (e.g. cell-ECM interactions, growth factor pathways), the three-dimensional collagen matrix environment appears to differentially regulate the activity of the control and disease cells.

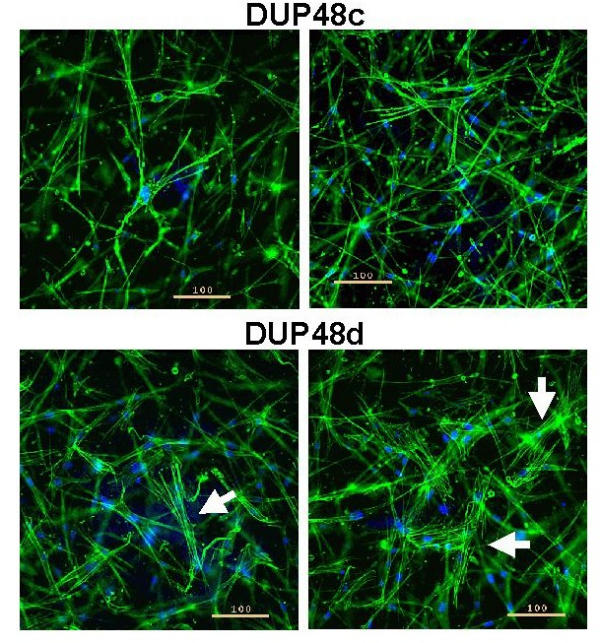

Figure 5.

ICC of FPCL cultures. Depicted are representative images from disease (d) and normal/control (c) matched primary culture (patient DUP48). The cells were grown as attached FPCLs for 2 days (105 cells/ml of matrix). Cells were then fixed and stained with phalloidin-Alexa 488 (green) and DAPI (blue) to label both F-actin and the nucleus, respectively. Digital images were acquired on a Nikon eclipse TE-200 inverted fluorescent microscope (10x objective) using a Photometrics series 300 cooled CCD camera, and deconvolved using softWoRx (v 2.5) software (Applied Precision Inc., Issaquah WA, USA). Arrows identify prominent F-actin networks (stress fibres) within the diseased cells. The scale bar denotes 100 μ.

Western analysis of stressed and attached FPCLs

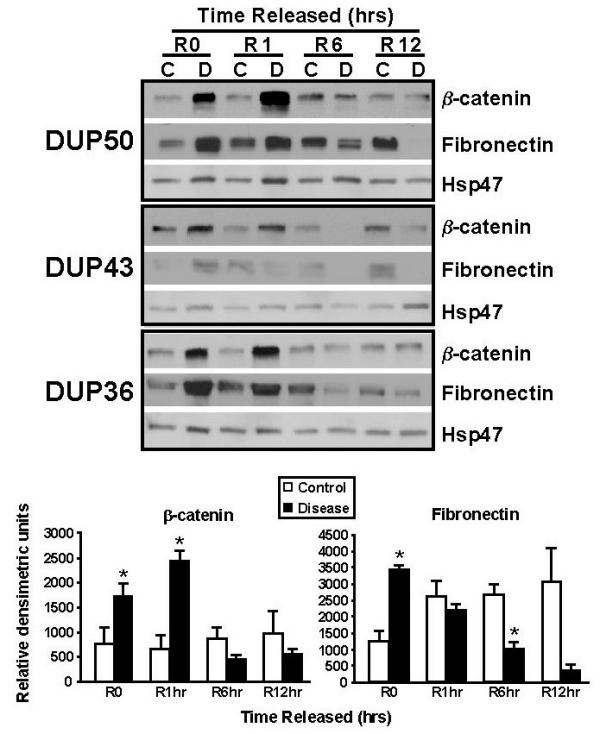

Since β-catenin is aberrantly expressed in vivo and in vitro (FPCL cultures) in DD [13], we examined its levels in relation to changes in mechanical stress (stressed- or attached-matrices). Fibronectin (Fn) levels were also examined since it plays an important role in cell-collagen interactions [43,50,51], and the regulation and function of β-catenin [52,53]. During the contraction of stressed-FPCLs β-catenin levels transiently increased in disease cells, peaking at 1 hr post-mechanical release (R1, Dis/ctrl ratio = 3.6) and decreasing thereafter to levels equivalent to, or below those seen in control FPCLs, while in control matrix cultures β-catenin levels did not significantly change throughout the incubation period (Fig. 6). By contrast, Fn levels in disease FPCLs (R0, Dis/ctrl ratio = 2.7) steadily decreased upon mechanical release of the matrices, while Fn levels in control lattices showed a slight increase during contraction (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Western analysis of β-catenin and Fn in contracting FPCLs. The upper panel shows the western analysis results of contracting 'stressed' FPCLs of three patient-matched disease (D) and normal/control (C) primary cell lines (n = 3). FPCLs (3 lattices per cell line) were harvested at the indicated time points following mechanical release and homogenized for protein extraction. The resulting western blots were sequentially probed with β-catenin (1:750; clone 14, Transduction Laboratories), and Fn (clone IST-4, 1:500, Sigma) and Hsp47 (1:500, StressGen) antibodies. Antibody-specific bands for β-catenin and fibronectin and Hsp47 were quantified using NIH Imaging software, normalized to Hsp47 levels (ratio), and plotted (bar graphs, lower panel) as the mean ratio intensity ± SEM per time point.

While the observed decline in Fn levels in the disease FPCLs is consistent with previous studies that show disassemble of cellular Fn fibrils upon loss of isometric tension [54,55], the lack of change in Fn levels in the contracting control FPCLs is unclear. Nevertheless it is conceivable that the differences between the disease and normal fibroblasts with respect to stress-induced changes in Fn may simply reflect the disease-specific nature of these cells since Fn is a gene target of the β-catenin/Lef-Tcf transcriptional complex [52]. Considering that Fn can stimulate β-catenin nuclear accumulation via ILK (integrin-linked kinase) [56], and ILK itself can up-regulate Fn matrix assembly [57], it is possible that both β-catenin and Fn may share a common pathway within these cells. Although the mechanism responsible for the tension-dependent decrease in β-catenin is not clear it may also be related to the non-proliferative state of relaxed or floating FPCL cultures (Fig. 3) [58].

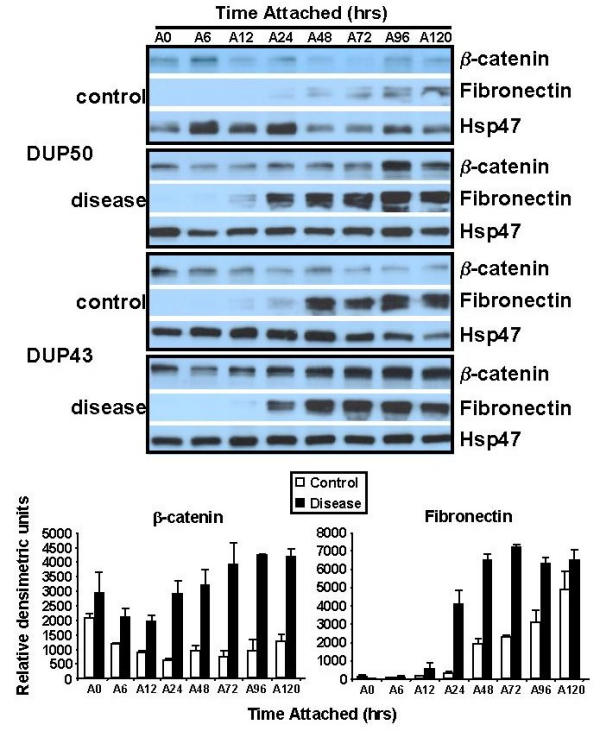

To further explore β-catenin and its relation to mechanical stress, we also analyzed β-catenin levels within attached-matrix (see Fig. 3) FPCL cultures. As shown in Fig. 7, western analysis of attached-matrices showed an accumulation of β-catenin in the disease cells over time, relative to control Hsp47 levels, while β-catenin levels remain relatively unchanged in the control cells. Although Fn levels in both control and disease cultures increased over the incubation period, Fn levels accumulated much faster within the disease FPCLs compared to control FPCL cultures (Fig. 7). Although the exact mechanism responsible for the tension stimulated accumulation of β-catenin is not clear it may be related to proliferative nature of attached-matrix cultures [58].

Figure 7.

Western analysis of β-catenin and Fn in attached FPCLs. Attached FPCLs (3 lattices per cell line) were harvested at the indicated time points, homogenized, and protein extract prepared for western analysis. Membranes were sequentially probed with β-catenin (1:750; clone 14, Transduction Laboratories), Fn (clone IST-4, 1:500, Sigma), and Hsp47 (1:500, StressGen) antibodies. Antibody-specific bands for β-catenin and fibronectin and Hsp47 were quantified using NIH Imaging software, normalized to Hsp47 levels (ratios), and plotted (bar graphs, lower panel) as the mean ratio intensity ± SEM per time point. Two patient-matched disease and normal/control primary cultures were examined.

Immunocytochemistry analysis of attached FPCLs

Given that Fn levels increase much earlier in the disease FPCL cultures, and that Fn matrix can regulate β-catenin levels, it is possible that disease cell cultures develop a peri-cellular Fn matrix (fibronexus) much earlier, and perhaps to a much greater extent, than control cells. Since previous studies have shown that the formation of filamentous actin (F-actin) networks parallels Fn matrix assembly [55], we probed FPCLs for F-actin expression using phalloidin-Alexa 488. Immunocytochemistry (ICC) analysis shows that the disease cells form extensive stress-fibres Fig. 5 and attach and spread within the collagen matrix much earlier than control cells Fig. 8, suggesting that the disease cells form a Fn matrix much earlier than control cells within attached-matrix cultures. While it is not clear whether β-catenin up regulates cellular Fn production, and/or cellular Fn stimulates increased β-catenin stability, it does appear that this altered metabolic state of the disease cells promotes cell-collagen attachment and cell-mediated collagen contraction. The build-up of isometric tension within the FPCL cultures likely accelerated this process since isometric tension can directly modulate cell signalling events important to fibroblast contractility [59], as well as stimulate the expression of contractile markers such as Fn and α-SM actin in vivo [60]. Moreover, the well recognized role that integrins (cell-ECM receptors) play in helping to generate isometric tension and Fn matrix assembly [51,61], suggests that integrin-mediated signalling factors, like ILK, may provide a possible mechano-chemical pathway linking isometric tension with changes in the β-catenin and Fn levels. Nevertheless, the possible relationship between β-catenin, Fn, ILK and other signalling factors remains to be examined.

Figure 8.

Morphology of DD cells under isometric tension in FPCLs. Depicted are attached (A) FPCL cultures of one representative patient-matched disease and control primary cell line (DUP36). FPCLs were harvested at the indicated attached time points (A0 – A48 hours). Lattices were fixed and stained for F-actin and DNA, using phalloidin-Alexa 488 (green) and DAPI (blue), respectively (Molecular Probes Eugene ON, USA). Digital images were acquired on a Nikon eclipse TE-200 inverted fluorescent microscope (10x objective) using a Photometrics series 300 cooled CCD camera. The scale bar denotes 100 μ.

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that primary cell cultures derived from DD lesions display a number of phenotypic differences when compared to patient-matched normal fascia primary cultures. FPCL and ICC analysis shows that DD cells are more contractile than control cells due, in part, to an enhanced filamentous actin network. Western analysis of disease and normal FPCLs show markedly elevated levels of β-catenin and Fn expression in disease cell lattices that are sensitive to changes in isometric tension. More specifically, in disease cultures β-catenin and Fn expression levels decrease dramatically when isometric tension is reduced, while continued culture under stress (attached FPCLs) stimulates increases in both Fn and β-catenin levels. ICC analysis also suggests that disease cells attach and spread more quickly in attached matrix cultures, and form more extensive F-actin networks than control cultures.

The clinical importance of tension in wound-scar formation [62] and postoperative management of DD patients [46], coupled with the tension-dependent changes in β-catenin levels observed in this study, suggests a possible mechano-chemical link between the aberrant expression of β-catenin in DD lesions [13] and tension-induced scar formations in fibro-proliferative disorders like DD. While the exact role of β-catenin in the patho-mechanisms of DD is unclear, future studies will be focussed on the relations between tension, β-catenin and the ECM.

List of abbreviations

ECM – extracellular matrix; FPCL – fibroblast populated collagen matrix; DD – Dupuytren's disease; PBS – phosphate buffered saline; ICC – immunocytochemistry; Wnt – wg (Wingless) + int-1 (integration site 1 of mouse mammary tumor virus); Fn – Fibronectin; Hsp47 – heat shock protein of 47 kDa; DAPI – 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride; Fz – Frizzled receptor; LRP – low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein; Cer – cerebrus; WIF-1 – wnt-interacting protein; sFRPs – secreted frizzled related proteins; Dkk – dickkopf-1; Dvl – dishevelled; GBP – GSK-3β Binding Protein; CKIε – casein kinase I ; GSK-3β – glycogen synthase kinase-3β; Tcf/Lef – T-cell factor-lymphoid enhancer factor; APC – adenomatous polyposis coli gene; ILK – integrin linked kinase; LDH – lactic dehydrogenase; SDS-PAGE – sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PVDF – polyvinylidene difuoride; PBST – PBS + Tween 20; HRP – horseradish peroxidase. RT – room temperature; HEPES – 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; α-MEM – alpha-minimal essential medium; FCS – fetal calf serum; PMSF – phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride.

; GSK-3β – glycogen synthase kinase-3β; Tcf/Lef – T-cell factor-lymphoid enhancer factor; APC – adenomatous polyposis coli gene; ILK – integrin linked kinase; LDH – lactic dehydrogenase; SDS-PAGE – sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PVDF – polyvinylidene difuoride; PBST – PBS + Tween 20; HRP – horseradish peroxidase. RT – room temperature; HEPES – 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; α-MEM – alpha-minimal essential medium; FCS – fetal calf serum; PMSF – phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

VMV carried out the FPCL experiments and western blots. BSG, DCR, JHR and KJF provided the clinical material used to establish primary cultures and participated in interpretation of results. BA participated in the design of the study. JCH and BSG conceived the studies, participated in the design and co-ordination of the study, analysed and interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (BSG, JCH, BA), Plastic Surgery Education Fund (BSG, JCH), Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation (JHR, JCH, BSG), American Society for Surgery of the Hand (DCR, JHR, JCH, BSG) and the Lawson Health Research Institute's Internal Research Fund (JCH, BSG).

Contributor Information

Jeffrey C Howard, Email: jhoward@lri.sjhc.london.on.ca.

Vincenzo M Varallo, Email: varallo@rogers.com.

Douglas C Ross, Email: dross@uwo.ca.

James H Roth, Email: james.roth@sjhc.london.on.ca.

Kenneth J Faber, Email: kjfaber@uwo.ca.

Benjamin Alman, Email: benjamin.alman@sickkids.ca.

Bing Siang Gan, Email: bsgan@lri.sjhc.london.on.ca.

References

- Dupuytren G. Permanent retraction of the fingers, produced by an affection of the palmar fascia. Lancet. 1834;2:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rayan GM. Clinical presentation and types of Dupuytren's disease. Hand Clin. 1999;15:87–96. vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergovich FR, Botz JS, McFarlane RM. Nonrandom cytogenetic abnormalities in Dupuytren's disease [letter] N Engl J Med. 1983;308:162–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurster-Hill DH, Brown F, Park JP, Gibson SH. Cytogenetic studies in Dupuytren contracture. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:285–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnici AV, Birjandi F, Spencer JD, Fox SP, Berry AC. Chromosomal abnormalities in Dupuytren's contracture and carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg [Br] 1992;17:349–55. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90128-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin P, De Smet L, Sciot R, Van Damme B, Van den Berghe H. Trisomy 7 and trisomy 8 in dividing and non-dividing tumor cells in Dupuytren's disease. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;108:137–40. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(98)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wever I, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD, Mandahl N, Mertens F, Mitelman F, Rosai J, Rydholm A, Sciot R, Tallini G, et al. Cytogenetic, clinical, and morphologic correlations in 78 cases of fibromatosis: a report from the CHAMP Study Group. CHromosomes And Morphology. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1080–5. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen OA, Hoyeraal HM, Sandvik L. Increased mortality in Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Surg [Br] 1999;24:515–8. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson KG, Arngrimsson R, Sigfusson N, Jonsson T. Increased total mortality and cancer mortality in men with Dupuytren's disease. A 15-year follow-up study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:5–10. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley MJ, Dale TC. Wnt signalling in mammalian development and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:215–30. doi: 10.1023/A:1006369223282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E, Lee JH, Abraham SC, Wu TT. Superficial fibromatoses are genetically distinct from deep fibromatoses. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:695–701. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varallo VM, Gan BS, Seney S, Ross DC, Roth JH, Richards RS, McFarlane RM, Alman B, Howard JC. Beta-catenin expression in Dupuytren's disease: potential role for cell-matrix interactions in modulating beta-catenin levels in vivo and in vitro. Oncogene. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagase H, Miyoshi Y, Horii A, Aoki T, Petersen GM, Vogelstein B, Maher E, Ogawa M, Maruyama M, Utsunomiya J, et al. Screening for germ-line mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis patients: 61 new patients and a summary of 150 unrelated patients. Hum Mutat. 1992;1:467–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380010603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Nishisho I, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Ando H, Horii A. Mutations of the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene in FAP (familial polyposis coli) patients and in sporadic colorectal tumors. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992;168:141–7. doi: 10.1620/tjem.168.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alman BA, Li C, Pajerski ME, Diaz-Cano S, Wolfe HJ. Increased beta-catenin protein and somatic APC mutations in sporadic aggressive fibromatoses (desmoid tumors) Am J Pathol. 1997;151:329–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejpar S, Nollet F, Li C, Wunder JS, Michils G, dal Cin P, Van Cutsem E, Bapat B, van Roy F, Cassiman JJ, et al. Predominance of beta-catenin mutations and beta-catenin dysregulation in sporadic aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) Oncogene. 1999;18:6615–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham SC, Reynolds C, Lee JH, Montgomery EA, Baisden BL, Krasinskas AM, Wu TT. Fibromatosis of the breast and mutations involving the APC/beta-catenin pathway. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:39–46. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon SS, Cheah AY, Turley S, Nadesan P, Poon R, Clevers H, Alman BA. beta-Catenin stabilization dysregulates mesenchymal cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness and causes aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;30:30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102657399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsken J, Birchmeier W, Behrens J. E-cadherin and APC compete for the interaction with beta-catenin and the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2061–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa M, Baribault H, Kemler R. The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. Embo J. 1989;8:1711–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Transmembrane control of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion: a 94 kDa protein functionally associated with a specific region of the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. Cell Regul. 1989;1:37–44. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3286–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–5. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli M, Dougan ST, Caldwell K, O'Keefe L, Schwartz S, Vaizel-Ohayon D, Schejter E, Tomlinson A, DiNardo S. arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature. 2000;407:527–30. doi: 10.1038/35035110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson KI, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery BJ, Skarnes WC. An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature. 2000;407:535–8. doi: 10.1038/35035124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature. 2001;411:321–5. doi: 10.1038/35077108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–42. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L. beta-catenin and its multiple partners: promiscuity explained. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:484–7. doi: 10.1038/88532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, van de Wetering M. TCF/LEF factor earn their wings. Trends Genet. 1997;13:485–9. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01305-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma [see comments] Science. 1997;275:1784–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ. beta-catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 1999;21:1021–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199912)22:1<1021::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J, Clevers H. TCF transcription factors: molecular switches in carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1424:M23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0304-419X(99)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Morin PJ, Clevers H. The Yin-Yang of TCF/beta-catenin signaling. Adv Cancer Res. 2000;77:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60783-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AJ, Sims TJ, Gabbiani G, Bazin S, LeLous M. Collagen of Dupuytren's disease. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:499–502. doi: 10.1042/cs0530499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin S, Le Lous M, Duance VC, Sims TJ, Bailey AJ, Gabbiani G, D'Andiran G, Pizzolato G, Browski A, Nicoletis C, et al. Biochemistry and histology of the connective tissue of Dupuytren's disease lesions. Eur J Clin Invest. 1980;10:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1980.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley-Parsons D, Glimcher MJ, Smith RJ, Albin R, Adams JP. Biochemical changes in the collagen of the palmar fascia in patients with Dupuytren's disease. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1981;63:787–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Hurst LC. The biochemistry of Dupuytren's disease. Hand Clin. 1999;15:35–42. v–vi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. Molecular biology of fibronectin. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:67–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek JJ, Schultz RJ, Haaksma CJ. Extracellular matrix-cytoskeletal connections at the surface of the specialized contractile fibroblast (myofibroblast) in Dupuytren disease. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1987;69:1400–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday NL, Rayan GM, Zardi L, Tomasek JJ. Distribution of ED-A and ED-B containing fibronectin isoforms in Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Surg [Am] 1994;19:428–34. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A, Borsi L, Luo X, Zardi L, Katenkamp D, Kosmehl H. Evidence of ED-B+ fibronectin synthesis in human tissues by non-radioactive RNA in situ hybridization. Investigations on carcinoma (oral squamous cell and breast carcinoma), chronic inflammation (rheumatoid synovitis) and fibromatosis (Morbus Dupuytren) Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;109:249–55. doi: 10.1007/s004180050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaga H, Kikuchi S, Yoshizato K. Collagen gel contraction by fibroblasts requires cellular fibronectin but not plasma fibronectin. Exp Cell Res. 1991;193:167–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alman BA, Greel DA, Ruby LK, Goldberg MJ, Wolfe HJ. Regulation of proliferation and platelet-derived growth factor expression in palmar fibromatosis (Dupuytren contracture) by mechanical strain. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:722–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloen P. New insights in the development of Dupuytren's contracture: a review. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:629–35. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RB, Dell PC, Fiolkowski P. A clinical report of the effect of mechanical stress on functional results after fasciectomy for Dupuytren's contracture. J Hand Ther. 2002;15:331–9. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(02)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek J, Rayan GM. Correlation of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and contraction in Dupuytren's disease fibroblasts. J Hand Surg [Am] 1995;20:450–5. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JL, Dodd C, Ghahary A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. The effect of interferon-alpha2b on an in vitro model Dupuytren's contracture. J Hand Surg [Am] 1999;24:578–85. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn MA, Wang X, Payne WG, Ko F, Robson MC. Tamoxifen Decreases Fibroblast Function and Downregulates TGF(beta2) in Dupuytren's Affected Palmar Fascia. J Surg Res. 2002;103:146–52. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G, Lanzafame S, Micali G. Co-ordinate expression of alpha 5 beta 1 integrin and fibronectin in Dupuytren's disease. Acta Histochem. 1995;97:229–33. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(11)80184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Sottile J, Langenbach KJ. Stimulation of integrin-mediated cell contractility by fibronectin polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10673–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradl D, Kuhl M, Wedlich D. The Wnt/Wg signal transducer beta-catenin controls fibronectin expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5576–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11211–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochitate K, Pawelek P, Grinnell F. Stress relaxation of contracted collagen gels: disruption of actin filament bundles, release of cell surface fibronectin, and down-regulation of DNA and protein synthesis. Exp Cell Res. 1991;193:198–207. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90556-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday NL, Tomasek JJ. Mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix influence fibronectin fibril assembly in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:109–17. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Hsu SC, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Radeva G, Papkoff J, Montesano R, Roskelley C, Grosschedl R, Dedhar S. Cell adhesion and the integrin-linked kinase regulate the LEF-1 and beta-catenin signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4374–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Keightley SY, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Radeva G, Coppolino M, Goicoechea S, McDonald JA, Dedhar S. Integrin-linked protein kinase regulates fibronectin matrix assembly, E-cadherin expression, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:528–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F. Signal transduction pathways activated during fibroblast contraction of collagen matrices. Curr Top Pathol. 1999;93:61–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-58456-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Ho CH, Lin YC, Skuta G. Differences in the regulation of fibroblast contraction of floating versus stressed collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:918–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Mastrangelo D, Iselin CE, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1009–20. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov R, Cukierman E, Katz BZ, Matsumoto K, Lin DC, Lin S, Hahn C, Yamada KM. Integrin dynamics and matrix assembly: tensin-dependent translocation of alpha(5)beta(1) integrins promotes early fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1075–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa AM, Peyrol S, Porto LC, Comparin JP, Foyatier JL, Desmouliere A. Mechanical forces induce scar remodeling. Study in non-pressure-treated versus pressure-treated hypertrophic scars. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1671–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo S, Agius E, Leyns L, Bhattacharyya S, Grunz H, Bouwmeester T, De Robertis EM. The head inducer Cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of Nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;397:707–10. doi: 10.1038/17820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC, Kodjabachian L, Rebbert ML, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, Samos CH, Nusse R, Dawid IB, Nathans J. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398:431–6. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner A, Hsieh JC, Smallwood PM, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nathans J. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2859–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim SH, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell. 1997;88:747–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Krinks M, Lin K, Luyten FP, Moos M., Jr Frzb, a secreted protein expressed in the Spemann organizer, binds and inhibits Wnt-8. Cell. 1997;88:757–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81922-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA. Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:683–6. doi: 10.1038/35083081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao B, Wu W, Davidson G, Marhold J, Li M, Mechler BM, Delius H, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Walter C, et al. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2002;417:664–7. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith J, Nusse R, Perrimon N. The Drosophila segment polarity gene dishevelled encodes a novel protein required for response to the wingless signal. Genes Dev. 1994;8:118–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer J, Klingensmith J, Perrimon N, Nusse R. dishevelled and armadillo act in the wingless signalling pathway in Drosophila. Nature. 1994;367:80–3. doi: 10.1038/367080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman DJ, Klingensmith J, Salinas P, Adams PS, Nusse R, Perrimon N. Isolation and characterization of a mouse homolog of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dishevelled. Dev Biol. 1994;166:73–86. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost C, Farr GH, 3rd, Pierce SB, Ferkey DM, Chen MM, Kimelman D. GBP, an inhibitor of GSK-3, is implicated in Xenopus development and oncogenesis. Cell. 1998;93:1031–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, McKay RM, McKay JP, Graff JM. Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;401:345–50. doi: 10.1038/43830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka C, Leong P, Xu L, Harrison SD, Williams LT. Casein kinase iepsilon in the wnt pathway: regulation of beta-catenin function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12548–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Fagotto F, Zhang T, Hsu W, Vasicek TJ, Perry WL, 3rd, Lee JJ, Tilghman SM, Gumbiner BM, Costantini F. The mouse Fused locus encodes Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates embryonic axis formation. Cell. 1997;90:181–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, Jerchow BA, Wurtele M, Grimm J, Asbrand C, Wirtz R, Kuhl M, Wedlich D, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with beta-catenin, APC, and GSK3 beta. Science. 1998;280:596–9. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, Muller O, Chamberlain SH, Masiarz FR, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science. 1993;262:1731–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8259518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Association of the APC tumor suppressor protein with catenins. Science. 1993;262:1734–7. doi: 10.1126/science.8259519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost C, Torres M, Miller JR, Huang E, Kimelman D, Moon RT. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1443–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Embo J. 1997;16:3797–804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart M, Concordet JP, Lassot I, Albert I, del los Santos R, Durand H, Perret C, Rubinfeld B, Margottin F, Benarous R, et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr Biol. 1999;9:207–10. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latres E, Chiaur DS, Pagano M. The human F box protein beta-Trcp associates with the Cul1/Skp1 complex and regulates the stability of beta-catenin. Oncogene. 1999;18:849–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]