Abstract

Polo-like kinases (Plks) play crucial roles in mitosis and cell division. Whereas lower eukaryotes typically contain a single Plk, mammalian cells express several closely related but functionally distinct Plks. We describe here a chemical genetic system in which a single Plk family member, Plk1, can be inactivated with high selectivity and temporal resolution by using an allele-specific, small-molecule inhibitor, as well as the application of this system to dissect Plk1's role in cytokinesis. To do this, we disrupted both copies of the PLK1 locus in human cells through homologous recombination and then reconstituted Plk1 activity by using either the wild-type kinase (Plk1wt) or a mutant version whose catalytic pocket has been enlarged to accommodate bulky purine analogs (Plk1as). When cultured in the presence of these analogs, Plk1as cells accumulate in prometaphase with defects that parallel those found in PLK1Δ/Δ cells. In addition, acute treatment of Plk1as cells during anaphase prevents recruitment of both Plk1 itself and the Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RhoGEF) Ect2 to the central spindle, abolishes RhoA GTPase localization to the equatorial cortex, and suppresses cleavage furrow formation and cell division. Our studies define and illuminate a late mitotic function of Plk1 that, although difficult or impossible to detect in Plk1-depleted cells, is readily revealed with chemical genetics.

Keywords: cell division, Ect2, knockout, mitosis

Members of the Polo-like kinase (Plk) family are critical for the proper timing and fidelity of chromosome segregation and cell division (1, 2). Humans and other mammals possess four distinct but closely related Plks. The most extensively studied of these isoforms, Plk1, has important functions throughout late G2 and early M phase (1, 2). Plk1 is also thought to be necessary for cytokinesis, but its exact contributions have been difficult to investigate, because the early mitotic defects caused by Plk1 depletion trigger the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), precluding direct observation of cell division. One solution would be to use small molecules that can rapidly inhibit Plk1 in anaphase, after the SAC has been satisfied. Some compounds that inhibit Plk1 activity in vitro have been reported (3–7), but their specificities in vivo are either poor or largely unknown. Although screening panels of kinases can provide one estimate of inhibitor selectivity, such in vitro assays are unavailable for most of the ≈500 kinases present in the human genome and would miss off-target effects on other relevant classes of enzymes, such as cytoskeletal motor proteins (8, 9). In addition, because of the strong conservation of the Plk kinase domain, none of these compounds is expected to be selective for individual Plk isoforms, complicating their use as precise surrogates of Plk1 depletion or genetic ablation.

In yeast, a powerful method for monospecific kinase inhibition involves replacing the target enzyme of interest with a variant whose catalytic pocket has been modified to accept bulky purine analogs (10). As these analogs cannot fit into the nucleotide-binding sites of endogenous kinases, they do not affect the growth of isogenic yeast strains lacking the mutant kinase, providing strong evidence of their specificity in vivo. We show here that a similar approach can be used in human cells to dissect kinase function with high temporal resolution and genetic specificity. Using gene targeting and transgenic complementation, we established somatic cell lines in which Plk1 activity was provided solely by an analog-sensitive mutant (Plk1as). Although Plk1as cells grew comparably to Plk1 wild-type (Plk1wt) cells, they were uniquely sensitive to two different purine analogs, arresting in mitosis with characteristic defects in spindle assembly, centrosome maturation, and chromosome alignment. In addition, acute inhibition of Plk1as during anaphase prevented cleavage furrow formation and cell division. This defect was accompanied by a failure to localize the RhoA GTPase, an essential regulator of actomyosin dynamics during cytokinesis, and its upstream guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Ect2 to the equatorial cortex and central spindle, respectively. Furthermore, Plk1's own recruitment onto the central spindle was also abolished. Our studies identify distinct functions of Plk1 throughout mitosis and cytokinesis and demonstrate the power of chemical genetics in dissecting these complex but short-lived events within human cells.

Results

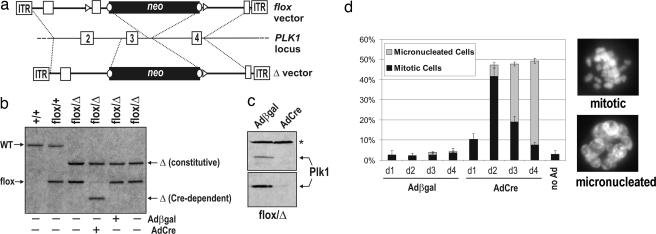

To develop a chemical genetic system for Plk1, we first needed to eliminate the endogenous kinase from human cells. We used adeno-associated virus vectors (11, 12) (Fig. 1a) to mutate both copies of the PLK1 locus in telomerase-expressing human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Because PLK1 is expected to be essential, one allele was deleted outright, whereas the other could be conditionally deleted by using Cre recombinase. After two rounds of targeting, we obtained several independent PLK1flox/Δ clones (Fig. 1b). These cells were infected with adenoviruses expressing Cre recombinase (AdCre) or adenoviruses expressing β-galactosidase (Adβgal) as a negative control. Over the next 24–48 h, the AdCre-infected cells ceased to express Plk1 (Fig. 1c) and accumulated in mitosis (Fig. 1d). As expected, many of these cells had severe spindle and centrosome maturation defects (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). Subsequently, the proportion of mitotic cells declined, and a new population of micronucleated cells appeared (Fig. 1d), which is indicative of “mitotic slippage” after chronic spindle dysfunction in this cell type (13). Thus, although retinal pigment epithelial cells can proliferate even when Plk1 levels have been severely (>90%) reduced through RNAi (14), homozygous deletion of PLK1 fully abrogates its function in vivo. This finding validated our gene targeting strategy, and more importantly, provided a tight genetic background for subsequent reconstitution experiments.

Fig. 1.

Conditional inactivation of PLK1 in human cells through gene targeting and Cre-mediated recombination. (a) Diagram of the PLK1 locus and adeno-associated virus vectors used to create floxed (PLK1flox) and null (PLK1Δ) alleles. loxP sites (triangles) and FRT sites (circles) are shown. (b) Southern blot analysis confirming gene replacements and Cre-induced recombination in PLK1flox/Δ cells. (c) Extracts from PLK1flox/Δ cells infected with Adβgal or AdCre were blotted with antibodies against the C terminus (Upper) or N terminus (Lower) of Plk1. The asterisk denotes a cross-reacting band used to confirm equal loading. (d) Cells infected as in c were scored for the fraction of interphase, mitotic, and micronucleated cells by Hoechst staining and fluorescence microscopy. Error bars denote SEM.

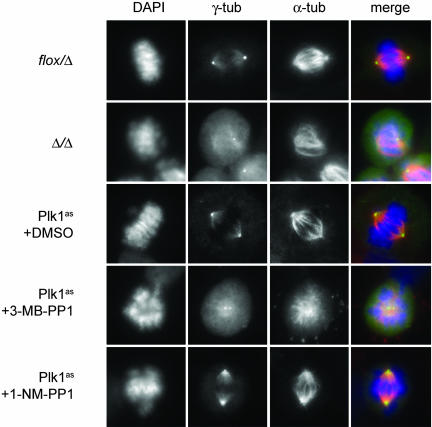

Fig. 3.

Comparison of early mitotic defects in PLK1-null and Plk1as cells. PLK1flox/Δ cells were infected with Adβgal or AdCre for 48 h. Plk1as cells were incubated for 10 h with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1, 10 μM 1-NM-PP1, or DMSO. Cells were stained with antibodies to γ-tubulin (γ-tub) (green) and α-tubulin (α-tub) (red) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Table 1.

Quantification of centrosomal and spindle defects in PLK1-null and Plk1as cells

| Cell line | Virus or compound | Separated centrosomes (%) | Unseparated centrosomes (%) | Normal bipolar spindles (%) | Disorganized bipolar spindles (%) | Monopolar spindles (%) | Multipolar spindles (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flox/Δ | Adβgal | 49 (98) | 1 (2) | 49 (98) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| flox/Δ | AdCre | 15 (30) | 35 (70) | 2 (4) | 19 (38) | 29 (58) | 0 (0) |

| Plk1as | DMSO | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 49 (98) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Plk1as | 1-NM-PP1 | 45 (90) | 5 (10) | 24 (48) | 21 (42) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Plk1as | 3-MB-PP1 | 25 (50) | 25 (50) | 10 (20) | 15 (30) | 25 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Plk1wt | 3-MB-PP1 | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| flox/Δ | 3-MB-PP1 | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 24 (96) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

Many protein kinases tolerate replacement of the gatekeeper residue (a conserved, bulky, and often hydrophobic residue that lines the ATP-binding site) to glycine, which enlarges the catalytic pocket enough to accommodate bulky purine analogs (10). However, ≈20% of all kinases, including the yeast Plk Cdc5, become minimally functional when this residue is mutated, unless a suppressor mutation in the amino-terminal lobe of the ATP-binding pocket is also present (15). On the basis of these observations, we transduced PLK1flox/Δ cells with retroviruses expressing either wild-type Plk1 (Plk1wt) or the equivalent double mutant (C67V L130G, hereafter referred to as Plk1as) as EGFP fusions. Both proteins localized to centrosomes and kinetochores in mitotic cells as expected [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. Upon AdCre infection and limiting dilution, we recovered EGFP-positive clones in which both PLK1 alleles had been deleted (i.e., a PLK1Δ/Δ genotype; SI Fig. 6), demonstrating functional rescue by both transgenes.

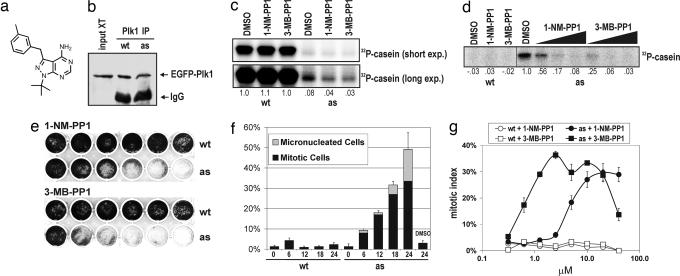

In vitro, Plk1as was able to use N6-(benzyl)-ATP and sensitive to the purine analogs 1-NM-PP1 (10) and 3-MB-PP1 (Fig. 2a), in contrast to Plk1wt, which was ≈12-fold more active than Plk1as in the presence of ATP (Fig. 2 b–d). In comparison, the widely used cdc28-as1 allele behaves comparably to CDC28 in genetic assays but encodes a kinase with a 50-fold lower kcat/Km for ATP than the wild-type enzyme (10). We therefore focused our attention on whether Plk1as conferred analog sensitivity in vivo. Both 1-NM-PP1 and 3-MB-PP1 inhibited the growth of Plk1as cells in a dose-dependent manner but had little effect on Plk1wt cells (Fig. 2e). Like PLK1Δ/Δ cells, inhibitor-treated Plk1as cells first accumulated in mitosis but then succumbed to mitotic slippage (Fig. 2f). In titrations, 3-MB-PP1 induced mitotic arrest at a 10-fold lower concentration than 1-NM-PP1 (Fig. 2g), paralleling its greater potency as a Plk1as inhibitor in vitro. Importantly, the kinetics of this arrest were much faster than with AdCre-mediated gene deletion, as expected for an inhibitory mechanism that does not rely on mRNA or protein turnover. Moreover, Plk1as cells resumed cell division once the inhibitor was removed (SI Fig. 7). From these data, we conclude that these compounds rapidly, selectively, and reversibly inhibit Plk1as in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Reconstitution of Plk1 function with Plk1as. (a) Chemical structure of 3-MB-PP1. (b–d) Nucleotide specificity and analog sensitivity of Plk1wt and Plk1as. Plk1 was immunoprecipitated from mitotic extracts and either immunoblotted (b) or incubated with casein and [γ-32P]ATP (c) or [γ-32P]N6-(benzyl)-ATP (d). Where indicated, 1-NM-PP1 or 3-MB-PP1 was added to the reactions (10 μM, c and left portion of d; 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM, right portion of d). Casein labeling is reported relative to DMSO-treated Plk1wt (c) or Plk1as (d) controls. (e) Plk1as cells are analog-sensitive. Cells were cultured in the presence of 1-NM-PP1 or 3-MB-PP1 (left to right: 0 μM, 0.078 μM, 0.313 μM, 1.25 μM, 5 μM, and 20 μM) for 8 days. (f) Inhibitor-treated Plk1as cells arrest in mitosis. Plk1wt and Plk1as cells were challenged with 10 μM 1-NM-PP1 and sampled at the indicated times. Percentages of mitotic and micronucleated cells were determined as in Fig. 1. (g) 3-MB-PP1 induces mitotic arrest at a 10-fold lower concentration than 1-NM-PP1. Plk1wt (open symbols) and Plk1as cells (closed symbols) were cultured for 18 h in the presence of 1-NM-PP1 (circles) or 3-MB-PP1 (squares). Mitotic indices were determined as above.

To evaluate the penetrance of Plk1 inactivation, we examined spindle assembly and centrosome maturation in analog-treated Plk1as cells by using PLK1Δ/Δ cells as a qualitative and quantitative reference for the null phenotype (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Confirming earlier studies (16–18), mitotic PLK1Δ/Δ cells had monopolar or disorganized bipolar spindles with adjacent and immature centrosomes, as reflected in poor concentration of γ-tubulin at the poles. In agreement with our titrations, there was a clear difference between 1-NM-PP1 and 3-MB-PP1 when applied to Plk1as cells at the same concentration (10 μM): Most 1-NM-PP1-treated cells had well separated centrosomes and bipolar spindles but incompletely aligned chromosomes (Fig. 3). By contrast, half of the 3-MB-PP1-treated cells had adjacent centrosomes and monopolar spindles, a fraction comparable to that observed in PLK1Δ/Δ cells (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Crucially, none of these defects was observed when Plk1wt or PLK1flox/Δ cells were treated with 3-MB-PP1, ruling out the possibility that they arose from an off-target activity against other endogenous cellular enzymes, including other Plk isoforms or microtubule motor proteins required for spindle bipolarity (1, 8). We conclude that, although both analogs inhibit Plk1as sufficiently to block cell proliferation and induce mitotic arrest, 3-MB-PP1 elicits a more penetrant phenotype that is virtually identical to PLK1 deletion. We therefore used 3-MB-PP1 for all subsequent analyses.

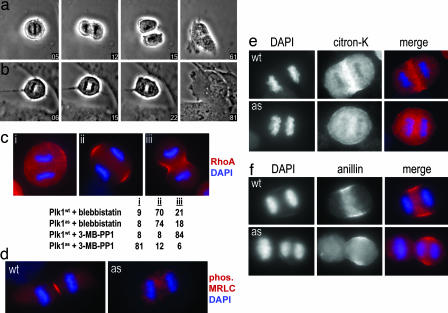

To determine whether our chemical genetic system could be used to probe Plk1's role in cytokinesis, we located metaphase cells and treated them with 3-MB-PP1 shortly before they entered anaphase. Whereas Plk1wt cells divided normally (n = 10 cells; Fig. 4a and SI Movie 1), furrows were either absent or highly labile in Plk1as cells, resulting in a single binucleated cell upon mitotic exit (n = 8 cells; Fig. 4b and SI Movie 2). Thus, Plk1's kinase activity is needed for an early event in cytokinesis. Given the well documented role of the small GTPase RhoA at the cleavage furrow (19), as well as recent data that the yeast Plk Cdc5 controls the local activation of the RhoA ortholog Rho1 at the site of cell division (20), we asked whether Plk1 regulates RhoA localization in dividing human cells. Plk1wt and Plk1as cells were synchronized in prometaphase with monastrol (8), were released into monastrol-free medium for 30 min to allow spindle bipolarization and silencing of the SAC, and then were treated for 20 min with 3-MB-PP1 (to inhibit Plk1as) or blebbistatin (to inhibit myosin II; see ref. 9) during anaphase (Fig. 4c). We confirmed that blebbistatin inhibits furrowing without affecting the cortical localization of RhoA (21–23), consistent with myosin II being a downstream target of RhoA (19). In contrast, 3-MB-PP1 suppressed both equatorial RhoA recruitment and furrowing in Plk1as cells, implying that Plk1 acts upstream of RhoA (Fig. 4c). Consistent with the lack of RhoA at the equatorial cortex, 3-MB-PP1-treated Plk1as cells also lacked the phosphorylated form of myosin regulatory light chain, which normally accumulates at the central spindle and contractile ring in response to RhoA signaling (n = 46 of 50 cells affected; Fig. 4d) (21–23). The RhoA-dependent localization of citron kinase (24, 25) was similarly lost upon Plk1 inhibition (n = 47 of 50 cells; Fig. 4e). A fourth component of the contractile ring, anillin (26), was partially affected by Plk1 inhibition. In Plk1wt cells, anillin was concentrated in an equatorial band and excluded from the poles. In contrast, although some anillin reached the equatorial cortex in inhibitor-treated Plk1as cells, a large fraction was dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (n = 30 cells; Fig. 4f). These results indicate that Plk1 activity is required for the equatorial localization of RhoA and its effectors during anaphase.

Fig. 4.

Acute inhibition of Plk1 during anaphase disrupts RhoA localization and blocks the onset of cytokinesis. (a and b) Metaphase Plk1wt (a) and Plk1as (b) cells were treated with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1 (time 0) and followed during progression into anaphase. Although chromatid separation occurred normally, Plk1as cells failed to divide and became binucleated (SI Movies 1 and 2). (c) Plk1 activity is required to localize RhoA at the equatorial cortex. Plk1wt and Plk1as cells were synchronized with monastrol, released for 30 min, and then treated for 20 min with either blebbistatin or 3-MB-PP1. RhoA accumulation at the equatorial cortex was visualized after trichloroacetic acid fixation (21, 27). Anaphase cells (n = 100 per sample) were classified with respect to equatorial RhoA staining and cleavage furrow formation. (d–f) Plk1wt and Plk1as cells were treated with 3-MB-PP1 and stained with antibodies against phosphorylated myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) (d), citron kinase (citron-K) (e), and anillin (f).

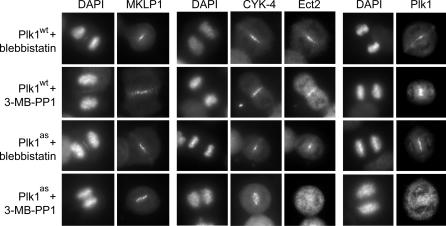

In animal cells, RhoA localization and furrow assembly are regulated by the RhoGEF Ect2, which is recruited to the central spindle by the Rho GTPase activating protein (GAP) CYK-4/MgcRacGAP and the kinesin MKLP1 (21–23, 27). Furthermore, Plk1 itself relocalizes onto the central spindle, making it an ideal candidate to regulate Ect2-mediated signaling. Intriguingly, whereas both MKLP1 and CYK-4 were recruited to the central spindle under all conditions (Fig. 5), Ect2 was dispersed throughout the cytoplasm in 3-MB-PP1-treated Plk1as cells (n = 48 of 50 cells delocalized). In addition, Plk1as itself was absent from the central spindle (n = 44 of 50 cells), which is consistent with a previous report that Plk1's targeting to this site requires phosphorylation of MKLP2 (28). We conclude that Plk1 activity controls not only the kinase's own recruitment at the central spindle but also that of Ect2, the critical GEF for RhoA during cytokinesis (19). Our results identify a clear requirement for Plk1 in activating the RhoA network at the start of cytokinesis, a function that, although in close temporal proximity to Plk1's early mitotic roles, could nonetheless be isolated by using chemical genetics.

Fig. 5.

Plk1 activity recruits both the RhoGEF Ect2 and Plk1 itself to the central spindle. Plk1wt and Plk1as cells were treated as in Fig. 4c. Whereas MKLP1 and CYK-4 localized correctly under all conditions, Ect2 and Plk1 were both absent from the central spindle after Plk1 inhibition.

Discussion

To date, defining the precise roles of Plk1 in mammalian cytokinesis has been difficult, because inactivating Plk1 by standard techniques results in spindle defects and SAC-dependent prometaphase arrest (17, 18). Efforts to circumvent this arrest (for example, through simultaneous inactivation of the SAC and Plk1) suggested that Plk1 may be dispensable for the initiation of cytokinesis in humans (18, 29). However, we found that acute inhibition of Plk1as in cells that entered anaphase spontaneously (i.e., after satisfying rather than bypassing the SAC) suppressed cleavage furrow formation. Furthermore, Plk1 activity is necessary to target both the kinase itself and the RhoGEF Ect2 to the central spindle, a structure that has an important instructive role in contractile ring assembly (19). When Plk1 is inhibited, RhoA and its effectors fail to localize at the presumptive furrow, readily explaining why cytokinesis fails to occur. Given the similarity of these effects to RNAi depletion of Ect2 or its binding partner CYK-4 (21–23, 27), we conclude that Plk1 is a critical upstream activator of the Ect2–RhoA network during cytokinesis. We speculate that, once localized to the central spindle, Plk1 stimulates Ect2's recruitment and/or GEF activity through phosphorylation, because Ect2 is a Plk1 substrate in vitro, and its interaction with CYK-4 is sensitive to phosphatase treatment (21, 30).

Current models place Ect2 and RhoA at the apex of a signal transduction pathway that stimulates the onset of cytokinesis, with additional factors, such as anillin, participating at later steps (19). Indeed, anillin is not required for either furrow formation or Ect2's central spindle recruitment (26, 31, 32), arguing that the mild delocalization of anillin in analog-treated Plk1as cells was not responsible for their early cytokinesis defects. Nevertheless, we do not exclude the possibility that regulation of anillin by Plk1 may be necessary for later stages of cytokinesis.

Our experience highlights three strengths of the chemical genetics approach. First, the bulky size of the purine analogs reduces the likelihood of off-target inhibition a priori, as the compounds are sterically occluded from the active sites of most if not all wild-type kinases. Second, the in vivo selectivity of these compounds was explicitly verified in each experiment, by ensuring that all phenotypes were linked to the analog-sensitive kinase. In principle such verification is possible with any bioactive small molecule (for example, by introducing an inhibitor-resistant version of the putative target into cells or organisms and assaying for functional rescue) but, to our knowledge, has not been conducted with existing Plk inhibitors. Third, because analog sensitivity is a genetically encoded trait, the same compounds can be used to inhibit more than one kinase in a manner equivalent to temperature shift in yeast genetics. For example, a similar strategy was recently used to replace Cdk7, the cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase (CAK), with an analog-sensitive version in human cells (33). Given the large number of kinases involved in mitosis and cytokinesis, as well as the short time scales on which these enzymes act, further chemical genetic analysis of the human cell division cycle should be highly informative.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Genetics.

Generation of adeno-associated virus particles and screening for gene-targeted clones was performed as described in refs. 11 and 12. Adenoviruses were used at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Plk1wt and Plk1as retroviruses were produced by cotransfection of retroviral and vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein envelope plasmids into Phoenix cells.

Immunofluorescence and Live-Cell Microscopy.

For detection of citron kinase and RhoA, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or 10% trichloroacetic acid and stained in accordance with published protocols (21–27). For all other antigens, cells were fixed with 100% methanol at −20°C and stained as described in ref. 21. Live-cell imaging was conducted on a temperature- and CO2-controlled microscope platform (11). For further details, see SI Movies 1 and 2.

Kinase Assays.

Plk1 was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell extracts, washed in lysis buffer (11) three times, once in kinase buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.4)/10 mM MgCl2/50 mM KCl/1 mM DTT], and then incubated in kinase buffer plus 5 μg of casein and [γ32P]ATP or [γ32P]N6-(benzyl)-ATP for 15–20 min at 30°C (9). 32P incorporation was quantified by SDS/PAGE and PhosphorImager (FujiFilm Medical Systems USA, Stamford, CT) analysis.

Chemicals.

1-NM-PP1 has been described in ref. 10. 3-MB-PP1 was synthesized by using a modified procedure (11). Monastrol (8) and blebbistatin (9) were used at 100 μM.

See SI Text for detailed protocols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Glotzer (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL) and G. Fang (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) for providing antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA107342 (to P.V.J.), GM56985 (to R.P.F.), and AI44009 (to K.M.S.) and a Clinical Scholar Award from the Charles A. Dana Foundation (to M.E.B.). P.V.J. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- Adβgal

adenoviruses expressing β-galactosidase

- AdCre

adenoviruses expressing Cre recombinase

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- Plk

Polo-like kinases

- Plk1wt

Plk1 wild type

- Plk1as

analog-sensitive Plk1 mutant

- SAC

spindle assembly checkpoint.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701140104/DC1.

References

- 1.van de Weerdt BC, Medema RH. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:853–864. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.8.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr FA, Sillje HH, Nigg EA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:429–441. doi: 10.1038/nrm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters U, Cherian J, Kim JH, Kwok BH, Kapoor TM. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:618–626. doi: 10.1038/nchembio826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McInnes C, Mazumdar A, Mezna M, Meades C, Midgley C, Scaerou F, Carpenter L, Mackenzie M, Taylor P, Walkinshaw M, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:608–617. doi: 10.1038/nchembio825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Shreder KR, Gai W, Corral S, Ferris DK, Rosenblum JS. Chem Biol. 2005;12:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson CS, Capper EA, Roshak AK, Marquez B, Eichman C, Jackson JR, Mattern M, Gerwick WH, Jacobs RS, Marshall LA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:858–866. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumireddy K, Reddy MV, Cosenza SC, Boominathan R, Baker SJ, Papathi N, Jiang J, Holland J, Reddy EP. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer TU, Kapoor TM, Haggarty SJ, King RW, Schreiber SL, Mitchison TJ. Science. 1999;286:971–974. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straight AF, Cheung A, Limouze J, Chen I, Westwood NJ, Sellers JR, Mitchison TJ. Science. 2003;299:1743–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.1081412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop AC, Ubersax JA, Petsch DT, Matheos DP, Gray NS, Blethrow J, Shimizu E, Tsien JZ, Schultz PG, Rose MD, et al. Nature. 2000;407:395–401. doi: 10.1038/35030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papi M, Berdougo E, Randall CL, Ganguly S, Jallepalli PV. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1029–1035. doi: 10.1038/ncb1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohli M, Rago C, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brito DA, Rieder CL. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1194–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Lei M, Erikson RL. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2093–2108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2093-2108.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C, Kenski DM, Paulson JL, Bonshtien A, Sessa G, Cross JV, Templeton DJ, Shokat KM. Nat Methods. 2005;2:435–441. doi: 10.1038/nmeth764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Erikson RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8672–8676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132269599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumara I, Gimenez-Abian JF, Gerlich D, Hirota T, Kraft C, De La Torre C, Ellenberg J, Peters JM. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1712–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Vugt MA, van de Weerdt BC, Vader G, Janssen H, Calafat J, Klompmaker R, Wolthuis RM, Medema RH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36841–36854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glotzer M. Science. 2005;307:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1096896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida S, Kono K, Lowery DM, Bartolini S, Yaffe MB, Ohya Y, Pellman D. Science. 2006;313:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1126747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuce O, Piekny A, Glotzer M. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:571–582. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura Y, Yonemura S. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:104–114. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamijo K, Ohara N, Abe M, Uchimura T, Hosoya H, Lee JS, Miki T. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:43–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalamalasetty RB, Hummer S, Nigg EA, Sillje HH. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3008–3019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eda M, Yonemura S, Kato T, Watanabe N, Ishizaki T, Madaule P, Narumiya S. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3273–3284. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.18.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao WM, Fang G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33516–33524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao WM, Fang G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13158–13163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neef R, Preisinger C, Sutcliffe J, Kopajtich R, Nigg EA, Mayer TU, Barr FA. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:863–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seong YS, Kamijo K, Lee JS, Fernandez E, Kuriyama R, Miki T, Lee KS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32282–32293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niiya F, Tatsumoto T, Lee KS, Miki T. Oncogene. 2006;25:827–837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oegema K, Savoian MS, Mitchison TJ, Field CM. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:539–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straight AF, Field CM, Mitchison TJ. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:193–201. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larochelle S, Merrick KA, Terret ME, Wohlbold L, Barboza M, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Jallepalli PV, Fisher RP. Mol Cell. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.