Abstract

Genetic mosaics produced by FLP/FRT induced mitotic recombination have been widely used in Drosophila to study gene function in development. Recently, the Cre/loxP system has been applied to induce mitotic recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells and in many adult mouse tissues. We have used this strategy to generate a previously undescribed p53 mouse model in which expression of a ubiquitously expressed recombinase in a heterozygous p53 knockout animal produces mitotic recombinant clones homozygous for the p53 mutation. The induction of loss of heterozygosity in a few cells in an otherwise normal tissue mimics genetic aspects of tumorigenesis more closely than existing models and has revealed the possible cell autonomous nature of Wnt3. Our results suggest that inducible mitotic recombination can be used for clonal analysis of mutants in the mouse.

Keywords: genetic mosaics, tumor, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, loss of heterozygosity, mouse model

Mutant mice generated by conventional or conditional targeting strategies provide valuable models for various hereditary diseases (1), but they do not exactly mimic spontaneous diseases caused by the accumulation of somatic mutations such as cancer (2). One widely studied cancer model is the heterozygous p53 knockout mouse (3–5), which models some aspects of Li–Fraumeni syndrome (6, 7). In these models, tumors arise from cells that have lost the remaining wild-type allele and have become p53-deficient. Because the loss of heterozygosity (LOH) event is stochastic, this limits the usefulness of this model. Alternative models have been described, in which the deletion of p53 is restricted to a few compartments as a result of the conditional expression of a recombinase such as Cre (8–10). However, in these models, the reduction to homozygosity affects almost all of the cells in an organ in which the recombinase is expressed, contrasting with the typical genesis of cancer that usually arises from a single mutant cell in an otherwise normal tissue (2).

Induced mitotic recombination (11–14) can potentially provide an alternative method to generate homozygous mutant cells in a nonmutant background at a relatively low frequency but under tissue specific and temporal control (Fig. 1). Induced mitotic recombination also provides an opportunity to test the genetic interaction between pairs of alleles that are linked on the same chromosome. Here, we report a p53 mouse model in which the wild-type p53 allele in a heterozygous p53 knockout animal can be lost by the induction of a ubiquitously expressed recombinase. The induction of LOH in a few cells in an otherwise normal tissue mimics genetic aspects of tumorigenesis more closely than existing models and has revealed the possible cell autonomous nature of Wnt3.

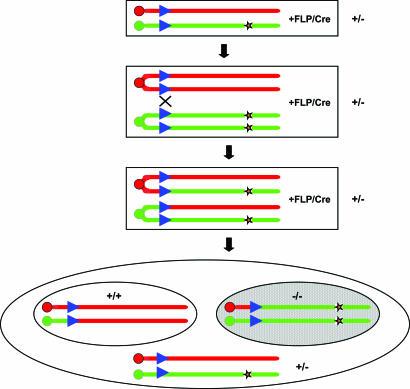

Fig. 1.

Basic strategy for mosaic studies. Mice carrying the mitotic recombination cassettes and a targeted mutation (orange star) are crossed to mice carrying Cre or FLP recombinase to generate mosaic animals. Expression of the recombinase in mice heterozygous for the targeted mutation induces mitotic recombination at G2. Recombinant chromatids follow G2-X segregation and produce cells homozygous for the mutation (shaded area). Blue triangle, FRT/loxP site; red and green bars, homologous chromosomes targeted by the mitotic recombination cassettes.

Results and Discussion

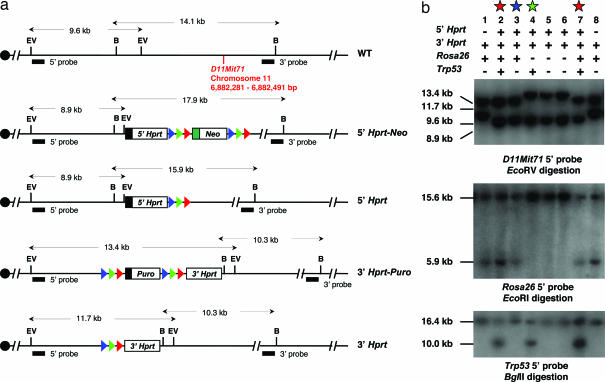

To functionally test mitotic recombination in vivo, a mouse line was generated in which mitotic recombination could be induced by two different site specific recombinases, FLP and Cre. Two cassettes with FRT and lox sites and complementary halves of an Hprt selection cassette were targeted to the D11Mit71 locus (12) at the proximal end of chromosome 11 (Fig. 2a). Transient expression of FLP or Cre in ES cell lines in which both cassettes had been targeted to the homologous chromosomes generated HAT-resistant clones that confirmed the functionality of the FRT and lox sites in vitro. Appropriately targeted cell lines were used to establish these alleles in mice. Further crosses with mice that carried the p53Brdm2 allele (15, 16) and a Rosa26-FLP knockin allele (17) were conducted to establish a cohort of p53-FLP mice in which induced mitotic recombination of p53 could be tested (Fig. 2b). A second experimental group (p53-Wnt3-FLP) was established containing the Rosa26-FLP knockin, the recombination cassettes and mutations in both p53 and Wnt3 (15, 18). In this experimental cohort, we are specifically testing whether the loss of Wnt3 has any impact on tumorigenesis induced by loss of p53. To control for any possible effect of targeting both alleles of the D11Mit71 locus, a group was established that contained the recombination cassettes and the p53Brdm2 allele but lacked the recombinase (Fig. 2b). To control for the possible effect of mitotic recombination, a second control group was established containing both recombination cassettes and the recombinase but wild-type p53 alleles (Fig. 2b). Mice lines were all established in a mixed 129S7/SvEvBrd-Hprtb-m2:C57BL/6 background.

Fig. 2.

Structure of mitotic recombination alleles. (a) Schematic of the D11Mit71 locus in wild-type, 5′ Hprt-Neo and 3′ Hprt-Puro alleles. The Neo and Puro selection markers were removed by Cre or FLP-mediated recombination to generate 5′ Hprt and 3′ Hprt targeted alleles without drug selection markers. Blue triangle, lox5171; green triangle, lox2272; red triangle, FRT site; black box, PGK promoter; green box, PolII promoter; EV, EcoRV; B, BamHI. (b) Southern blot analysis was performed on all of the progeny to identify their genotype at the D11Mit71, Rosa26, and Trp-53 loci (see Experimental Procedures). D11Mit715′Hprt/3′Hprt; Trp-53+/Brdm2; Rosa26+/Fki animals (p53-FLP mice, red star) were examined for the development of tumors. D11Mit715′Hprt/3′Hprt; Trp-53+/Brdm2; Rosa26+/+ mice (p53 controls, green star) were used as a control group for the effect of homozygosity at the D11Mit71 locus on p53 tumorigenesis. D11Mit715′Hprt/3′Hprt; Trp-53+/+; Rosa26+/Fki mice (Hprt control mice, blue star) were used as a control group for the effect of inducible mitotic recombination on tumorigenesis.

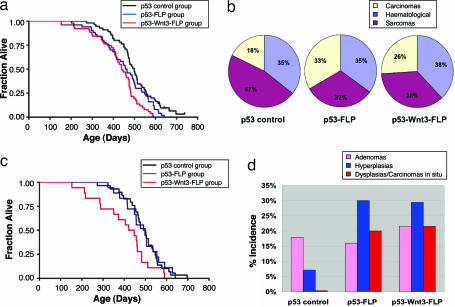

A cohort of 50 p53-FLP mice and 51 p53-Wnt3-FLP mice and controls was monitored for the development of tumors (Fig. 3a). The control groups did not show any evidence that the insertion of the recombination cassettes into the D11Mit71 locus affected p53-tumorigenesis or that mitotic recombination alone contributed to tumorigenesis [supporting information (SI) Table 2]. All of the mice in the two experimental groups died with tumors within a 2-yr observation period. Kaplan–Meier log-rank analysis shows that, although the p53-FLP group do not quite reach significance (P = 0.05), the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice died significantly quicker than the controls (P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Inducible mitotic recombination accelerates tumor latency and alters tumor spectrum. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis of the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice for all tumors compared with the p53 controls. There is a highly significant difference in survival between p53-Wnt3-FLP mice and p53 controls (P < 0.01). Statistical analysis of the p53-FLP mice vs. p53 controls does not quite reach significance (P = 0.05). The mean survival times of the p53-FLP, p53-Wnt3-FLP, and p53 control mice are 461, 440, and 499 days, respectively. (b) Tumor spectra in p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice compared with p53 controls. There is a reduction in sarcomas and an increase in carcinomas in the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. (c) Survival curve analysis of the p53-FLP, p53-Wnt3-FLP, and p53 control mice for sarcomas only. There is a significant reduction in survival in the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice compared with the p53 controls (P = 0.03). The mean survival times of the p53-Wnt3-FLP, p53-FLP, and p53 control mice with sarcomas are 399, 487, and 490 days, respectively. (d) Incidence of benign and premalignant lesions in p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice compared with p53 controls. There is an increase of benign lesions in the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. Dysplasias and carcinomas in situ are seen in both the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice but not the p53 controls.

The Kaplan–Meier plots are a tertiary measurement of the consequence of the genotype and reflect an averaging process associated with the affect of several different tumor types. Analysis of the spectrum of malignant tumors developing in the different lines (Table 1 and Fig. 3b) reveals that the p53-mitotic recombination mice developed approximately twice as many carcinomas and fewer sarcomas compared with the p53 controls. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the sarcomas as a separate group reveals that, although fewer sarcomas develop in the p53-Wnt3-FLP lines, they appear to be more aggressive cancers, because they kill the mice earlier (P < 0.03) (Fig. 3c and SI Fig. 6). By contrast, the sarcomas in the p53-FLP mice show a very similar profile to those that develop in the p53 controls.

Table 1.

Incidence of malignant and benign lesions in p53-FLP, p53-Wnt3-FLP, and p53 controls

| Tumor/lesion type | No. of tumors (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| p53 control(n = 56) | p53-FLP (n = 50) | p53-Wnt3-FLP (n = 51) | |

| Malignant tumors | |||

| Hematological | 22 (35%) | 20 (35%) | 19 (38%) |

| Sarcomas | 29 (47%) | 18 (32%) | 18 (36%) |

| Carcinomas | 11 (18%) | 19 (33%) | 13 (26%) |

| Total | 62 | 57 | 50 |

| Benign lesions | |||

| Adenomas | 10 (18%) | 8 (16%) | 11 (22%) |

| Hyperplasias | 4 (7%) | 15 (30%) | 15 (29%) |

| Dysplasias/CIS | 0 (0%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) |

| Total | 14 | 33 | 37 |

The tumor spectrum is represented by the percentage of total maligancies. Incidence is represented by the percentage of total cohort.

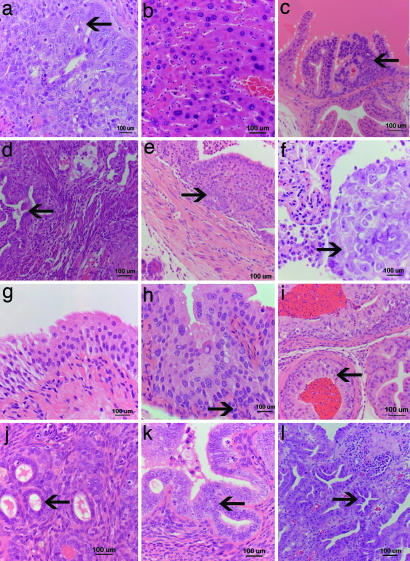

Detailed histopathological analysis has revealed that not only is there an increase in the proportion of carcinomas in the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice, but there is also a much greater diversity in this tumor set. In the p53 controls, 82% (9/11) of the carcinomas are pulmonary adenocarcinomas or hepatocellular carcinomas (Fig. 4 a and b), which is comparable to other p53 models (3, 4). However, these two carcinomas comprise only 47% (9/19) in the p53-FLP mice and 31% (4/13) in the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice, respectively. In addition to the lung adenocarcinomas and hepatocellular carcinomas, the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice also develop a diverse spectrum of tumors from the urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts (Fig. 4 c–f and SI Table 3). In particular, some rare malignancies were identified in the p53-Wnt3-FLP group (Fig. 4 e and f). The p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice also have a much higher incidence of lesions in epithelial tissues identified at necropsy (Table 1 and Fig. 3d), both benign (hyperplasias) as well as premalignant lesions (dysplasias and carcinoma in situ) (Fig. 4 g–l). By contrast, no cases of dysplasia or carcinoma in situ were observed in the p53 control group (Fig. 3d). Thus, in epithelial tissues, induced LOH of p53 appears to result in the generation of premalignant lesions, but further mutations are required for these to progress to full malignancy. However, it is also possible that the Rosa26-FLP transgene is more active in the epithelial cells.

Fig. 4.

Wide spectrum of epithelial lesions induced by mitotic recombination. (a and b) The majority of carcinomas occurring in the p53 control mice were pulmonary adenocarcinomas (a) and hepatocellular carcinomas (b). Mitoses are shown (arrow). (c–f) Carcinomas in the p53-FLP group and the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice also occur in the urogenital and gastrointestinal tract. Mitoses are shown (arrow). For example, prostatic carcinoma (c), uterine endometrial adenocarcinoma in the p53-FLP mice (e), pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma (d), and a rare epithelial mesothelioma of the pleural cavity and pericardium (f) in the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. (g–l) Premalignant changes (dysplasias) were identified only in the p53-FLP and the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. Normal bladder urothelium (g); dysplastic bladder urothelium with abnormally large nuclei with irregular chromatin (arrow) found in the p53-FLP mice (h); prostate intraepithelial neoplasia found in the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice; prostatic glands are lined by epithelium with large irregular nuclei and increased mitoses (i); normal endometrium with small tubular endometrial glands (arrow) (j); atypical endometrial hyperplasia with irregularly shaped endometrial glands lined by abnormal epithelium with enlarged elongated nuclei (arrow) found in the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice (k); and gastric intraepithelial dysplasia found in the p53-FLP mice (l). Gastric glands are irregular in shape with enlarged nuclei with irregular chromatin and multiple mitoses (arrow).

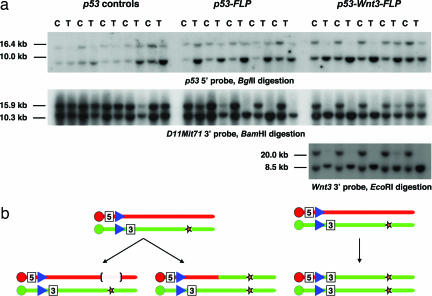

The difference in the survival curves and alterations in the tumor spectrum suggests that induced mitotic recombination is affecting tumor formation in p53 heterozygous animals. To further substantiate this observation, we have analyzed the tumors in all three groups for their allelic status at the D11Mit71, p53, and Wnt3 loci (Fig. 5). This analysis revealed that 27/37 (77%) of the tumors arising in the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice had LOH of the p53 allele, whereas this was observed in only 8/17 (47%) of the control tumors (SI Table 4). The LOH rate of the control tumors is comparable to previous observations (19, 20). Moreover, all but one of the tumors showing LOH of p53 was homozygous for the 3′ Hprt allele, confirming that LOH was caused by induced mitotic recombination. However, all of the control tumors showing LOH for p53 retained heterozygosity at D11Mit71. The tumors from the p53-Wnt3-FLP mice also showed LOH of Wnt3 and were thus also null for Wnt3.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of LOH. (a) Southern blot analysis of tumor samples from the p53 controls, p53-FLP, and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. D11Mit71 3′, p53 3′, and Wnt3 3′ probes were used to identify the LOH events in the tumor samples (see Experimental Procedures). Five tumor samples showing LOH of p53 were chosen from each group to check their allelic status at p53, D11Mit71 and Wnt3 loci. C, control samples not showing LOH of p53; T, tumor samples showing LOH of p53. (b) Mechanisms of LOH in the p53 controls, p53-FLP, and p53-Wnt3-FLP mice. The LOH events in the p53 controls occurred by a chromosomal deletion or duplications (Left). However, most LOH events in the p53-FLP and p53-Wnt3-FLP were induced by recombination between the two mitotic recombination cassettes (Right).

Induced LOH enables the genetic interaction of linked loci to be explored in tumorigenesis. In this study, null alleles of p53 and Wnt3 have been examined, and the absence of Wnt3 appears to influence the survival time of mice with sarcomas (Fig. 3c). Wnts are secreted molecules and are generally considered to be protooncogenes; thus, it would not be expected that loss of Wnt3 would have a cell autonomous effect in a small clone of p53-deficient cells expanding in a wild-type tissue environment. However, recent evidence has shown that Wnt5a behaves as a tumor suppressor gene in hematopoietic tissue (21). Wnt3 inhibits the cell cycle of both stromal and mesenchymal stem cells by the β-catenin signaling pathway (22). Moreover, recombinant dickkopf-1 (dkk-1), an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, increased the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and a dkk-1 antibody that blocks Dkk slows the growth of an osteosarcoma cell line (23). Thus, Wnt3 might be essential not only for mesoderm formation (18) but also for mesoderm-derived tissue homeostasis in the adult. However, it is also possible that when the induced mutant clones grow, the Wnt-deprived environment at the center will prevent the progression of tumorigenesis in some tissues.

In this study, we have used mitotic recombination to induce mosaics of a tumor suppressor gene in vivo. The induction of LOH in a few cells in an otherwise heterozygous p53 tissue mimics genetic aspects of tumorigenesis and has revealed the possible cell autonomous nature of Wnt3. Although this is a good genetic model of loss-of-function Li–Fraumeni mutations in humans, it does not exactly mirror the most common human situation in which p53-deficient tumors develop in a wild-type rather than a heterozygous p53 background. In this model, it is also possible that haploinsufficient functions of p53 in the surrounding tissue could contribute to clonal growth of cells that have lost p53. Because inducible recombination affects all loci distal to the recombination site, this technology provides a means to study interactions between genes on the same chromosome. Because of the relatively large inventory of rare carcinoma types in the mitotic recombination animals, this inducible mitotic recombination system could be used to model these rare cancers by restricting the expression of Cre to specific cell types. The indexed library of mutagenic insertion and chromosome engineering resource clones (24, 25) facilitates the use of this genetic system for other chromosomes and genes.

Experimental Procedures

Generation of Inducible Mitotic Recombination Mice.

Two inducible mitotic recombination cassettes were targeted to the D11Mit71 locus in wild-type AB2.2 ES cells by using standard procedures. Clones with the appropriate targeted allele were identified by Southern blot analysis. Several targeted clones with the 5′ Hprt cassette (WW14) and the 3′ Hprt cassette (WW16) were injected into C57TyrBrdC1 blastocysts and germ-line transmission was obtained for both alleles. Cre- or FLP-mediated deletion of the selection markers flanked by mutant lox and FRT sites was achieved in vivo by crossing mice with the D11Mit715′Hprt-Neo and D11Mit713′Hprt-Puro alleles to Cre (26) or FLP (17) deletor mice (SI Text).

Genotyping of p53 Mosaic Mice and Tumor Samples.

Southern blot analysis was performed on genomic DNA from tail or tumor samples to identify their genotype at the D11Mit71, Rosa26, p53, and Wnt3 loci. A D11Mit71 5′ probe using an EcoRV restriction digest identifies a 9.6-kb wild-type allele, an 8.9-kb 5′ Hprt cassette targeted allele, or a 13.4-kb 3′ Hprt cassette targeted allele. After Cre- or FLP-mediated deletion, the size of the 3′ Hprt targeted allele is reduced from 13.4 to 11.7 kb, and the 5′ Hprt targeted allele remains unchanged. A D11Mit71 3′ probe using a BamHI digest identifies a 14.1-kb wild-type allele, a 17.9-kb 5′ Hprt cassette targeted allele, or a 10.3-kb 3′ Hprt cassette targeted allele. After Cre- or FLP-mediated deletion, the size of the 5′ Hprt targeted allele is reduced from 17.9 to 15.9 kb, and the 3′ Hprt targeted allele remains unchanged. A Rosa26 3′ probe on a EcoRI digest identifies a 15.6-kb wild-type and a 5.9-kb targeted allele (17). A p53 5′ probe using a BglII digest identifies a 16.4-kb wild-type and a 10.0-kb targeted allele (15, 16). A Wnt3 3′ probe on a EcoRI digest identifies a 20-kb wild-type and a 8.5-kb targeted allele (18, 27) (SI Text).

Histological Analysis.

Mice were monitored for the appearance and growth of tumors; those with signs of illness or an obvious tumor burden were killed and subjected to a complete necropsy. All of the major organs and macroscopically identified tumors were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned, and stained by using standard procedures. Images were captured by using a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) Axioskop 2 plus microscope with Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera.

Statistical Analysis.

Survival curves were analyzed by GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA); the standard for significance was P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pentao Liu (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, London, U.K.) for the original inducible mitotic recombination cassettes; Francis Law and Alistair Beasley for feeder cell preparation; Beverley Haynes, Clare Brookes, and Diane Walters for histological technical assistance; Michael Robinson for animal surveillance; and Pentao Liu and Xiaozhong Wang for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Grant 79643.

Abbreviation

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

See Commentary on page 4245.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0607953104/DC1.

References

- 1.Austin CP, Battey JF, Bradley A, Bucan M, Capecchi M, Collins FS, Dove WF, Duyk G, Dymecki S, Eppig JT, et al. Nat Genet. 2004;36:921–924. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purdie CA, Harrison DJ, Peter A, Dobbie L, White S, Howie SE, Salter DM, Bird CC, Wyllie AH, Hooper ML, et al. Oncogene. 1994;9:603–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr Ann Intern Med. 1969;71:747–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969;43:1365–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, Peterse H, van der Valk M, Berns A. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meuwissen R, Linn SC, Linnoila RI, Zevenhoven J, Mooi WJ, Berns A. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flesken-Nikitin A, Choi KC, Eng JP, Shmidt EN, Nikitin AY. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3459–3463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golic KG. Science. 1991;252:958–961. doi: 10.1126/science.2035025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Nat Genet. 2002;30:66–72. doi: 10.1038/ng788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu T, Rubin GM. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng B, Sage M, Cai WW, Thompson DM, Tavsanli BC, Cheah YC, Bradley A. Nat Genet. 1999;22:375–378. doi: 10.1038/11949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng B, Vogel H, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:433–435. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.4.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. Genesis. 2000;28:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu P, Wakamiya M, Shea MJ, Albrecht U, Behringer RR, Bradley A. Nat Genet. 1999;22:361–365. doi: 10.1038/11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatachalam S, Shi YP, Jones SN, Vogel H, Bradley A, Pinkel D, Donehower LA. EMBO J. 1998;17:4657–4667. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Jacks T. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang H, Chen Q, Coles AH, Anderson SJ, Pihan G, Bradley A, Gerstein R, Jurecic R, Jones SN. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiba H, Kobune M, Kato J, Kawano Y, Ito Y, Nakamura K, Asakura S, Hamada H, Niitsu Y. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:1194–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory CA, Singh H, Perry AS, Prockop DJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28067–28078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng B, Mills AA, Bradley A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2354–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams DJ, Biggs PJ, Cox T, Davies R, van der Weyden L, Jonkers J, Smith J, Plumb B, Taylor R, Nishijima I, et al. Nat Genet. 2004;36:867–871. doi: 10.1038/ng1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su H, Mills AA, Wang X, Bradley A. Genesis. 2002;32:187–188. doi: 10.1002/gene.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu P, Zhang H, McLellan A, Vogel H, Bradley A. Genetics. 1998;150:1155–1168. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.3.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.