Abstract

Erythropoietin (EPO) is the hormonal regulator of red cell production and provided the paradigm for oxygen-regulated gene expression that led to the discovery of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). In this issue of the JCI, Rankin and colleagues show, using targeted gene inactivation, that induction of Epo expression in murine liver is dependent on the integrity of HIF-2α, and not HIF-1α (see the related article beginning on page 1068). These results demonstrate distinct functions for different HIF-α isoforms that could potentially be exploited in therapeutic approaches to anemia.

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hematopoietic growth factor that, by regulating production of red cells, controls one of the key determinants of physiological oxygen homeostasis, blood oxygen-carrying capacity. In the adult, EPO is produced mainly by the kidneys but also by the liver, and recombinant EPO has been established as the mainstay of treatment of certain types of anemia, particularly anemia associated with chronic kidney disease. In response to severe hypoxia, levels of EPO mRNA and EPO protein production by subsets of cells within the kidneys and liver can increase 1,000-fold or more. This striking response was an initial focus for studies of oxygen-regulated gene expression, and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) was defined as the central transcriptional mediator of this process (1). When investigators first probed the molecular pathways underlying oxygen-regulated transcription of the EPO gene, an entirely unanticipated finding was that the pathways involved were widespread and not confined to cells in the kidneys and liver that respond to hypoxia by the production of EPO (2). It is now recognized that the HIF system operates in essentially all cells and can directly or indirectly regulate hundreds of genes whose patterns of response to hypoxia and whose physiological functions are quite distinct from those of EPO. These include genes involved in functionally diverse responses such as cell motility and differentiation, matrix metabolism, and angiogenesis; genes with contrasting kinetic responses to hypoxia such as the massively inducible EPO gene versus the modestly inducible genes encoding glycolytic enzymes; and genes encoding proteins with apparently opposing physiological functions, such as growth factors and proapoptotic mediators (3). The unexpected pleiotropism of the HIF transcriptional cascade presumably underpins the complexity of oxygen homeostasis, but it begs a fundamental question as to how the system could orchestrate such diverse responses.

The oxygen-sensitive HIF hydroxylase pathway

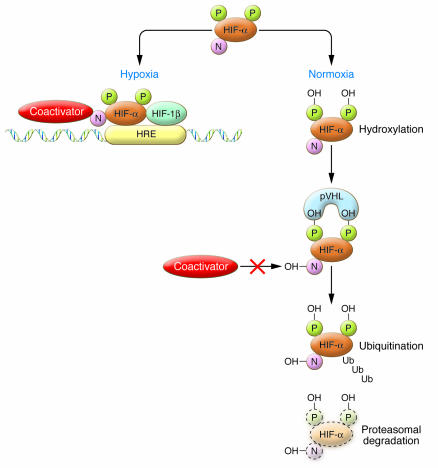

HIF is an α/β heterodimer that binds hypoxia response elements (HREs) at target gene loci under hypoxic conditions (Figure 1). In the presence of oxygen, HIF is inactivated by posttranslational hydroxylation of specific amino acid residues within its α subunits. Prolyl hydroxylation promotes interaction with the von Hippel–Lindau protein (pVHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex and proteolytic inactivation by proteasomal degradation, while asparaginyl hydroxylation blocks coactivator recruitment. These hydroxylation steps are catalyzed by a set of non-heme Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate–dependent dioxygenases whose absolute requirement for molecular oxygen confers sensitivity to hypoxia (4). So, how might such an apparently simple pathway transduce hypoxia signaling with the precision required to maintain physiological oxygen homeostasis, and how might the existence of different HIF-α isoforms contribute to this process? Answers to these questions should interest a range of medical scientists; both those seeking to understand the basic biology of oxygen homeostasis and those seeking to assess the feasibility of manipulating hypoxia signaling pathways for therapeutic purposes.

Figure 1. HIF activity under hypoxic and normoxic conditions.

In normoxia, hydroxylation at 2 proline residues promotes HIF-α association with pVHL and HIF-α destruction via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway, while hydroxylation of an asparagine residue blocks association with coactivators. In hypoxia, these processes are suppressed, allowing HIF-α subunits (both HIF-1α and HIF-2α) to escape proteolysis, dimerize with HIF-1β, recruit coactivators, and activate transcription via HREs. N, asparagine; P, proline; OH, hydroxyl group; Ub, ubiquitin.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α isoforms

HIF-1α was the original HIF isoform identified by affinity purification using oligonucleotides from the EPO locus (1), while HIF-2α and HIF-3α were identified by homology searches or screens for interaction partners with HIF-1β. HIF-3α is the more distantly related isoform and, in certain splicing arrangements, encodes a polypeptide that antagonizes HRE-dependent gene expression. However, HIF-1α and HIF-2α are closely related, and both activate HRE-dependent gene transcription (3). Nevertheless, knockout studies in mice demonstrate that HIF-1α and HIF-2α play nonredundant roles, and inactivation of each one results in a distinctly different phenotype. This may result, in part, from differences in tissue-specific and temporal patterns of induction of each isoform (5–7), but, not uncommonly, both isoforms are expressed within a given cell type, and the results of several studies, including those reported in this issue by Rankin et al. (8), suggest that HIF-1α and HIF-2α may have distinct transcriptional targets. If so, might distinct transcriptional responses to HIF-1α and HIF-2α be integrated in a way that supports a particular type of physiological adaptation to hypoxia? Recent findings do suggest that this may be the case, though our current understanding is far from clear.

Thus, the transcription of genes encoding enzymes that operate in a coordinated way in the glycolytic pathway appears to be driven by HIF-1α and not HIF-2α (9). A more fundamental question concerns the role (if any) of HIF-α isoform selectivity in coordinating more complex patterns of response such as the dichotomy between prosurvival and proliferative responses to hypoxia on the one hand and apoptotic and antiproliferative responses to hypoxia on the other. Evidence of distinct roles for HIF-1α and HIF-2α in regulating cell differentiation and in promoting the growth of certain tumors might be taken to support this (10, 11). HIF-2α has been associated with, and appears to promote, an undifferentiated phenotype in pluripotential cells (7, 12). Distinct roles for HIF-1α versus HIF-2α in promoting tumor growth have, so far, been most clearly defined in von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease–associated clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC). The tumor suppressor gene VHL, which is mutated in the majority of CCRCs, encodes the recognition component of the ubiquitin ligase that directs hydroxylated HIF-1α and HIF-2α to the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. When VHL is inactivated, both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are stabilized and the HIF transcriptional cascade is constitutively activated (4, 10). For reasons that remain unclear, in neoplastic epithelial cells of CCRCs, the normal predominance of HIF-1α expression in nonneoplastic renal tubules (5) is altered strikingly in favor of HIF-2α expression. Furthermore, genetic manipulation in CCRC cells indicates that activation of HIF-2α but not HIF-1α promotes tumor growth (13, 14). This parallels patterns of transcriptional selectivity in CCRCs whereby HIF-2α drives the expression of genes encoding prosurvival factors such as VEGF, TGF-α, and cyclin D1, whereas HIF-1α drives the expression of genes encoding proapoptotic factors such as BCL2/adenovirus E1B–interacting protein 1, NIP3 (BNIP3) (14). However, these results are observed in advanced cancer and CCRC-derived cell lines and appear to be somewhat different from those observed in non–CCRC-derived cells (7, 9, 14). Thus, they may reflect events that alter HIF-α transcriptional selectivity during tumor growth and not an intrinsic pattern of HIF-α transcriptional selectivity that is manifest in tissues of the intact organism. Interestingly, other data support the existence of cell-, condition-, or even disease-specific alterations in the transcriptional activities of HIF-1α and HIF-2α. It has been reported that in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, HIF-2α is transcriptionally inactive and retained in the cytoplasm (15), while evidence has been provided for a titratable repressor that restricts the activity of nuclear HIF-2α in embryonic stem cells (16). Thus, it appears that, superimposed on target gene–specific patterns of transcriptional selectivity, are one or more additional levels of control that limit or enhance the activity of HIF-2α in certain contexts.

Regulation of Epo by HIF-2α

Induction of erythropoiesis via the prosurvival growth factor EPO represents a discrete physiological response to hypoxia and a credible therapeutic target. Though the results of studies of constitutive inactivation of HIF-α isoforms have suggested that, at least under some circumstances, both HIF-1α or HIF-2α contribute to the EPO-mediated response, these studies are potentially confounded by effects of systemic HIF-α inactivation and have not permitted a clear comparison of the activities of the two isoforms (17, 18). In this issue of the JCI, Rankin and colleagues present a thorough analysis of conditional inactivation of HIF-1α and/or HIF-2α in the hepatocytes of mice (8). In each of four different situations associated with enhanced hepatic EPO expression (pVHL inactivation, early postnatal life, anemia, and chemical stimulation by hypoxia mimetics), the authors show that this response is either dominantly or exclusively dependent on the integrity of HIF-2α rather than HIF-1α. The results of this work are consistent with several other previously reported observations linking HIF-2α with Epo regulation; a previous study using siRNA to suppress the expression of HIF-α isoforms specifically in Hep3B cells reported a dominant role for HIF-2α in induction of Epo production (19). In normal kidney, the Epo gene is expressed in interstitial fibroblasts (20), a cell type that dominantly expresses HIF-2α (5). Excessive erythrocytosis (abnormally high numbers of red blood cells) is a well-recognized, though generally late, complication of CCRC. Paradoxically, Epo is expressed by the (neoplastic) tubular epithelium, which normally expresses only HIF-1α (21). However, as described above, during CCRC development there is a shift toward epithelial expression of HIF-2α; again there is an association between HIF-2α and Epo expression. The data reported in the current study by Rankin and colleagues (8) provides firm genetic evidence for a selective transcriptional connection between HIF-2α and Epo, at least in hepatocytes.

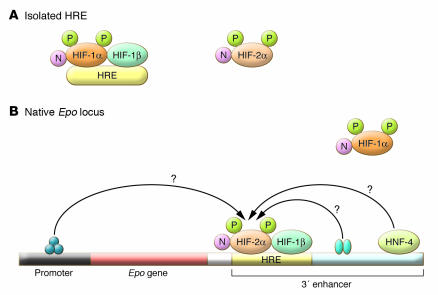

The study by Rankin et al. (8) also provides insight into two additional issues. Expression of the mRNA of the HIF target gene transferrin (which encodes an iron transport protein), like that of Epo, was shown to be dominantly regulated by HIF-2α. Based on this, the authors speculate that HIF-2α might be responsible for hypoxic induction of other genes whose functions may be involved in the promotion of erythropoiesis. Though there is little collateral support for this theory at present, this is certainly an interesting and testable hypothesis. Second, the authors speculate that the results of this study might enable development of more specific approaches to the therapeutic modulation of EPO, or at least specific therapeutic activation of HIF-2α. Inhibition of HIF hydroxylases by 2-oxoglutarate (cosubstrate) analogs has the potential to activate the HIF response pharmacologically, and it will be interesting to determine whether the design of HIF-α–selective inhibitors that might preferentially activate HIF-2α is feasible. In addition, Rankin and colleagues show that whereas an isolated HRE from the Epo locus binds HIF-1α preferentially, HIF-2α is preferentially bound at the HRE in the Epo 3' enhancer in its native context (Figure 2). They speculate that interactions between HIF and other transcription factors bound at the native Epo locus might promote selective recruitment of HIF-2α to this site. If this is true, a better understanding of these processes might provide insight into the basic biology of how specific responses to hypoxia are orchestrated and, potentially, how specific pharmacological manipulation of hypoxia pathways might be used to induce the production of Epo in the treatment of anemia.

Figure 2. Cooperative interactions at the Epo locus that are proposed to direct preferential binding of HIF-2α.

While the isolated HRE preferentially binds HIF-1α (A), in this issue of the JCI Rankin et al. (8) show that HIF-2α binds preferentially at the HRE within the native Epo 3' enhancer (B) and propose that cooperative interactions with other transcription factors bound to the 3' enhancer, to the promoter, or to other cis-acting sequences enable HIF-2α to bind preferentially to this HRE. The position of a hepatic nuclear factor–4 (HNF-4) binding site within the enhancer, which is a candidate participant in this action, is marked.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: CCRC, clear cell renal carcinoma; Epo, erythropoietin; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; HRE, hypoxia response element; pVHL, von Hippel–Lindau protein; VHL, von Hippel–Lindau.

Conflict of interest: The author is a founding scientist of ReOx Ltd.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 117:862–865 (2007). doi:10.1172/JCI31750.

See the related article beginning on page 1068.

References

- 1.Wang G.L., Jiang B.-H., Rue E.A., Semenza G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maxwell P.H., Pugh C.W., Ratcliffe P.J. Inducible operation of the erythropoietin 3′ enhancer in multiple cell lines: evidence for a widespread oxygen sensing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. . 1993;90:2423–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenger R.H. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2-sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2-regulated gene expression. . FASEB J. 2002;16:1151–1162. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0944rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schofield C.J., Ratcliffe P.J. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:343–354. doi: 10.1038/nrm1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberger C., et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a and -2a in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:1721–1732. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000017223.49823.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesener M.S., et al. Widespread, hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2a in distinct cell populations of different organs. FASEB J. 2002;17:271–273. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0445fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmquist-Mengelbier L., et al. Recruitment of HIF-1a and HIF-2a to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2a promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rankin E.B., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor–2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. . J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1068–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI30117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu C.-J., Wang L.-Y., Chodosh L.A., Keith B., Simon M.C. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a (HIF-1a) and HIF-2a in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaelin W.G. Molecular basis of the vhl hereditary cancer syndrome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:673–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covello K.L., Simon M.C., Keith B. Targeted replacement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by a hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha knock-in allele promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2277–2286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covello K.L., et al. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo K., Kico J., Nakamura E., Lechpammer M., Kaelin W.G.J. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raval R.R., et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S.-K., et al. Hypoxia-induced gene expression occurs solely through the action of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a (HIF-1a): role of cytoplasmic trapping of HIF-2a. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:4959–4971. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4959-4971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu C.J., et al. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:3514–3526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3514-3526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu A.Y., et al. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:691–696. doi: 10.1172/JCI5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scortegagna M., et al. HIF-2alpha regulates murine hematopoietic development in an erythropoietin-dependent manner. Blood. 2005;105:3133–3140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnecke C., et al. Differentiating the functional role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha (EPAS-1) by the use of RNA interference: erythropoietin is a HIF-2alpha target gene in HepB and Kelly cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1462–1464. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1640fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maxwell P.H., et al. Identification of the renal erythropoietin-producing cells using transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 1993;44:1149–1162. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Silva J.L., et al. Tumour cells are the site of erythropoietin synthesis in human renal cancers associated with polycythemia. Blood. 1990;75:577–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]