Abstract

Increasing emphasis is being placed on the importance of information technology to improve the safety and quality of healthcare. However, concern is growing that these potential benefits will not be equally distributed across the population because of a widening digital divide along racial and socioeconomic lines. In this pilot study, we surveyed 31 Medicaid beneficiaries to ascertain their interest in and projected use of a healthcare patient Internet portal. We found that most Medicaid beneficiaries (or their parents/guardians) were very interested in accessing personal health information about themselves (or their dependents) online. Additionally, they were interested in accessing healthcare services online. We also found that many Medicaid beneficiaries have Internet access, including a slight majority with access to high-speed Internet connections. Our study revealed significant concern about the privacy of online health information.

Introduction

Information technology has been identified as a critical element for reshaping healthcare in the United States to reduce errors and improve quality.1 Enabling patient access to their own health records is part of this strategy.2 A recent review of the literature suggests that allowing patients access to their medical records may improve record accuracy and communication with providers.3 Patient portals are being promoted as a mechanism to enable patients to access their health information and to obtain healthcare services. However, along with the potential benefits from improving patient access to records and services, there is also growing concern about a widening digital divide leading to increasing healthcare disparity.4 Evidence of a digital divide is supported by the observation that low income Americans have only half the Internet access of wealthier Americans.5 Hsu et al.4 showed that non-whites of lower socioeconomic status were less likely to use electronically available health information resources within a privately insured patient population. Weingart et al.6 observed that users of a patient portal were younger and more affluent than non-users further supporting evidence of a digital divide. Furthermore, Fowles et al.7 reported that nonwhite race and male gender were associated with lower interest in looking at online health records.

In contrast, the Fowles’ study found that education and income were not independently associated with interest. Additionally, Carroll et al.8 showed only a relatively small effect of education and household income on comfort using the Internet.

These conflicting observations from prior research raise a question whether or not a patient Internet portal would be accessible to and used by Medicaid beneficiaries, a population characterized by low income and minority race. Therefore, the purpose of this pilot study was to survey Medicaid beneficiaries regarding their access to and use of the Internet as well as their interest in obtaining personal health information and services through a patient Internet portal.

Methods

Survey Development

The 30-question survey included the following ten constructs:

Medicaid insurance status

Access to and use of the Internet

Perceived usefulness of accessing 8 types of personal health information via the Internet

Perceived usefulness of accessing 5 types of services via the Internet

Preferred mode of obtaining access to health records (paper or electronic)

Internet privacy concerns

Projected frequency of use of a patient portal

History of work in a medical environment

Overall health status

Standard demographics (age, gender, race)

The 13 patient portal features included in the survey were identified through a review of the relevant literature5–7 and a comprehensive review of three patient Internet portals that are currently in use:

MyGroupHealth (GroupHealth Cooperative)9

Patient Gateway (Partners Healthcare)10

Shared Care Plan (Whatcom County)11

We created two versions of the survey instrument, one for a subject answering for him/herself, and a second for a parent/guardian answering for a minor child enrolled in Medicaid.

The survey instrument was assessed for face validity and comprehensibility by social workers and care managers who work directly with Medicaid beneficiaries, and by field testing on eight Medicaid beneficiaries.

Patient Population

The interview sample was drawn from a population of 17,070 Medicaid beneficiaries living in Durham County, North Carolina and participating in a Medicaid-sponsored care management program. This patient population was 66.7% African-American, 12.5% White, and 20.8% other races (predominantly Hispanic); and was comprised of 66% children. The maximum household income of Medicaid beneficiaries in North Carolina is 185% of the poverty level. From this population, we generated a list of 500 randomly selected patients who had a Medicaid claim during the past year. The study subjects were the adult patients or the parents/guardians of minor patients on this list. Subjects were contacted by telephone in sequential order until the study sample was obtained.

Patient Interview Process

Telephone interviewers used a call list that included up to three of the most recent telephone numbers for each subject. Interviewers attempted to reach subjects (or the parent/guardian of a minor) at least three times. More than three attempts were sometimes made due to callback requests from subjects or family members. Calls were conducted during daytime, evening and weekend hours in order to optimize opportunities to reach subjects. All call attempts followed a scripted protocol and were documented on paper call record forms. Subjects who agreed to participate were first read a consent form (requiring approximately 4 minutes) before completing the survey, which averaged 11 minutes. Respondents were sent a $10 gift card.

Data Management

Telephone interviewers recorded all subject responses on paper survey forms. The data were then entered into an Access database and verified for accuracy. The verified data was exported to an Excel spreadsheet, which was used for statistical analysis.

Data Analysis

Characteristics of the study population were tabulated after stratification on the survey version (parent/guardian or self report). Among the adult patients answering questions for themselves, comparisons between respondents and non-respondents for key characteristics including age, gender, and race were conducted to assess the validity of the sampling process. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare key respondent characteristics to perceived usefulness survey components. The sample size of this pilot study limited our ability to conduct multivariable analyses.

This study was approved by the Duke University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

Survey Participants

Characteristics of the survey respondents with regard to demographic data, Internet access, and patient-reported health quality are summarized in Table 1. To obtain 31 completed surveys, we made 347 calls to 149 subjects. Ninety-nine calls (28.5%) led to either disconnected or incorrect phone numbers; 214 calls (61.7%) were either unanswered or not able to reach the intended subject; and 34 calls (9.8%) reached the intended subject. Of these 34 subjects, 31 completed the survey and 3 refused for an overall survey response rate of 20.8% (31of 149) of the total sample and 91.2% (31of 33) of subjects who were actually reached by phone. Comparison of the adult respondent group and the adult non-respondent group revealed no statistically significant differences based on age, gender, or race. Demographic data for the non-responders in the parent/guardian group were not available since the characteristics of these individuals were not collected until they were reached by telephone.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Respondents

| All (n=31) | Parent*(n= 19) | Self (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (range) | 36.9 (22–62) | 35.2 (24–62) | 39.7 (22 – 58) |

| Female Gender | 28 (90%) | 17 | 11 |

| Non-white Race | 26 (84%) | 16 | 10 |

| Internet Access | 28 (90%) | 16 | 12 |

| Past Internet Use | 23 (74%) | 13 | 10 |

| Internet Health Info† | 16 (52%) | 11 | 4 |

| Worked in Med Envir‡ | 14 (45%) | 7 | 8 |

or guardian of a minor enrolled in Medicaid;

Used Internet in the past to access health related information;

Reported previous employment in a medical environment.

The children for whom the survey was answered by a parent or guardian were 53% female and had a mean age of 7.8 years (age range from 1 to 17 years).

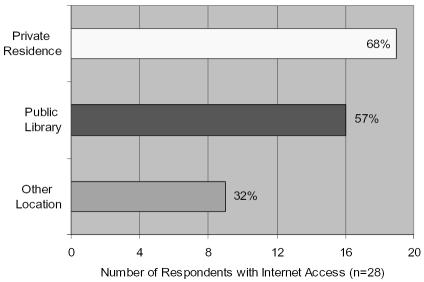

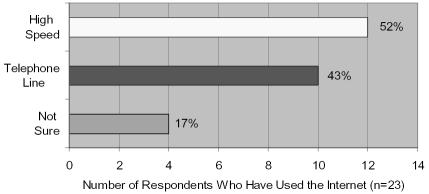

Respondent Type and Location of Internet Access

A majority of respondents (90.3%) had Internet access including several with access from multiple locations and many who had access from a private residence (Figure 1). Five respondents had Internet access available but did not use it. Of the 23 individuals who reported accessing the Internet, the majority had access to high-speed connections and some had access to more than one type of connection (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Internet Access Location

Figure 2.

Internet Access Type

Among the 28 respondents with Internet access, 21% used the Internet 5 to 7 days per week, 11% used the Internet 3 to 4 days per week, 36% used the Internet 1 to 2 days per week, and 32% used the Internet infrequently or not all.

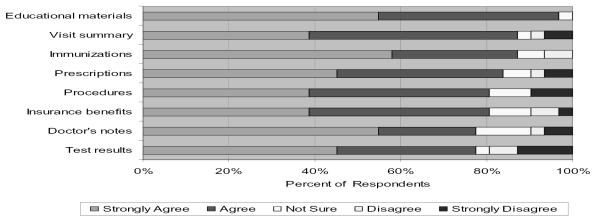

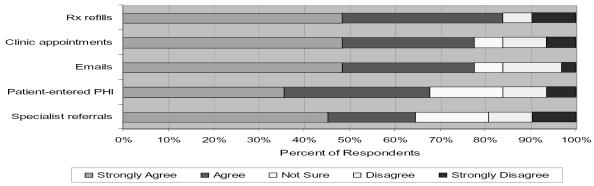

Patient Portal Content of Interest

The degree of patient interest in access to the personal health records for their dependents or for themselves, and to health care services is summarized in Figures 3 and 4, respectively (next page).

Figure 3.

Perceived Usefulness of Patient Portal Components

Figure 4.

Preceived Usefulness of Patient Portal Services

Overall, subjects were most interested in viewing office visit summaries, records of immunizations and a summary of prescriptions. They were least interested in viewing laboratory and other test results online. In addition, subjects were most interested in three online services: requesting prescription refills, making clinic appointments, and communicating with their care providers via email.

Association between Subject Characteristics and Perceived Usefulness of Portal Components

Table 2 shows the bivariate relationships between respondent characteristics and perceived usefulness of components of a patient Internet portal. These observations should be viewed as exploratory due to the limited sample size and the post-hoc nature of the analysis. A threshold of p<0.10 was used as a screening tool.

Table 2.

Comparison of Subject Characteristics and Perceived Usefulness of Portal Components.

| Past Internet Use | Internet Health Inform* | Worked in Medical Environment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Materials | |||

| Visit Summary | |||

| Immunizations | ♦ | ||

| Prescriptions | |||

| Procedures | ♦ | ||

| Insurance Benefits | |||

| Doctor’s Notes | |||

| Test Results |

indicates p<0.10 based on the Fisher’s Exact test for strong agreement (yes/no) with perceived usefulness component.

Subject characteristic of seeking health information on the Internet.

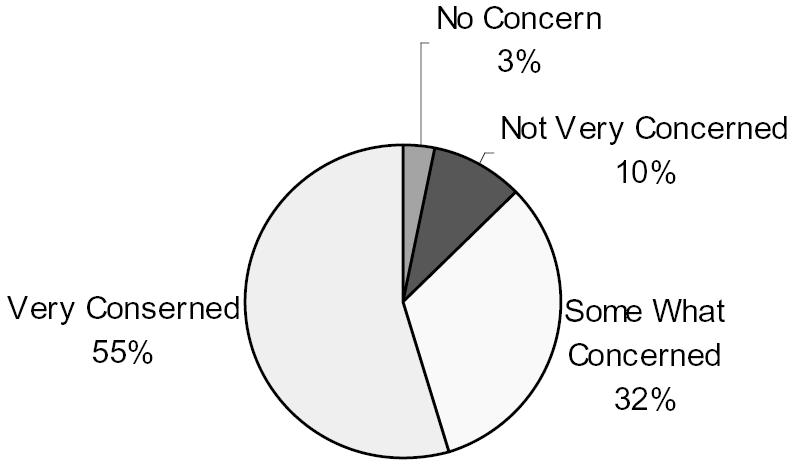

Privacy and Confidentiality Concerns

Patient concern regarding the privacy and confidentiality of their personal health information is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Concern about Privacy of Health Information Provided over the Internet

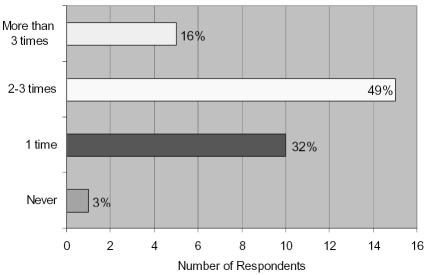

Estimated Patient Portal Use

The frequency with which respondents projected that they would access the health information for themselves or their dependents is summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Estimated Annual Use of Patient Internet Portal to View Electronic Health Records

When asked how they would like to receive their personal health information, 26% reported that they would like to have paper copies sent to them, 13% reported that they would like to view information online, 58% wanted both online access and a paper copy, and 3% wanted no copies.

Discussion

Through this pilot study, we have observed that Medicaid beneficiaries are very interested in viewing health information across all components of a patient portal for themselves or their dependents using the Internet. Medicaid beneficiaries also indicated that they would be willing to access healthcare services through the Internet including entering personal health information into an Internet-based patient portal (68% agreed or strongly agreed to the usefulness of entering information about their health online). Additionally, we have shown that many Medicaid beneficiaries do have access to high-speed Internet connections (52%). However, a sizable minority of the respondents relied on telephone modems, which could have significant design implications for a Medicaid patient portal.

In comparison to a previous survey study of interest in a patient Internet portal among a suburban, middle-class, privately insured population,7 our Medicaid respondents had slightly different priorities regarding the components in which they were most interested. Our respondents were most interested in educational materials, visit summaries and immunization records, where as the subjects from the previous study were most interested in test results, the item of least interest to our respondents. Our findings also are in contrast to the study on patient Internet portal use by Weingart et al.6 that found that laboratory and radiology results were the most often accessed component of the patient portal by a predominantly privately insured patient population.

Our pilot study also showed that Medicaid beneficiaries are very concerned about having their personal health information available online. These findings are similar to other national studies that looked at patient concern regarding the privacy of online health information.12 In particular, these studies indicated that the greatest amount of concern was among racial and ethnic minorities and individuals with lower amounts of education.

Even though subjects indicated significant concern about privacy of health information provided over the Internet, 64.5% of subjects indicated they would view their personal health information more than once a year. This projected frequency of accessing the patient Internet portal by our Medicaid subjects is within the 22% to 77% range of monthly access observed by Weingart et al.6 but is considerably higher than that obtained by Fowles, et. al,7 who found that only 10.8% of privately insured patients were interested in viewing their health records more than once a year.

This pilot study is limited by the relatively small sample size that lessens our ability to generalize these findings to all Medicaid beneficiaries. Additionally, because this was a telephone interview-based survey, the findings may reflect a selection bias in that only subjects who could be reached by telephone were included in a sample. As with any survey, there is also a potential response bias in that responders may have greater interest in accessing their health information online than non-responders. In this study, we were able to determine that there were no demographic differences between the responders and non-responders to the survey. Additionally, another limitation is that activities that subjects report they may do in a survey could be quite different from what they actually do in practice. Finally, we must recognize that the responses may overestimate interest in accessing health information online because respondents may have preferentially selected socially more desirable answers.

The implications of this pilot study are that patient portals may be useful to the Medicaid population; however, such portals should be designed for access by telephone modem and will probably be accessed a few times a year by a given individual. Furthermore, concerns about the privacy of online health information will need to be allayed among Medicaid beneficiaries in order to foster user buy-in.

For the future, a greater number of Medicaid beneficiaries should be surveyed and sample screens of the proposed patient Internet portal should be assessed in field studies. Further studies could ascertain if the associations suggested by this study (Table 2) are valid and significant.

Conclusion

Increasing concern about the broad impact of the potential benefits from greater use of information technology in healthcare may be justified because of a widening digital divide along racial and socioeconomic lines. In this study we sought to ascertain the projected interest in and use of a healthcare patient Internet portal among Medicaid beneficiaries. We found that Medicaid beneficiaries show a strong interest in accessing personal health information about themselves and their dependents online. In addition, many Medicaid beneficiaries have access to the Internet. These findings suggest that a patient Internet portal may be readily utilized by Medicaid beneficiaries. Our study also showed that, while there was significant interest in viewing health information through a patient Internet portal, the estimated actual use of such a resource would be a few times per year. As with other studies, this study also showed significant concern about the privacy of online personal health information.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Sherri Gerringer for assisting with telephone interviews and Frederick S. Johnson, MBA for coordinating activities with the Medicaid beneficiary network. This study was funded in part by H2ATH00998 from the Office for the Advancement of Telehealth of the Health Resources and Services Administration.

References

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Error Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams K, Greiner AC, Corrigan JM, editors. Crossing the Quality Chasm, A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross SE, Lin C-T. The effects of promoting patient access to medical records : a review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:129–138. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu J, Huang J, Kinsman J, Fireman B, Miller R, Selby J, Ortiz E. Use of e-health services between 1999 and 2002: A growing digital divide. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:164–171. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox S. How Californians compared to the rest of the nation: A case study sponsored by the California Health Care Foundation. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2003. [(accessed March 14, 2006)]. Wired for health. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_CA_Health_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weingart SN, Rind D, Tofias Z, Sands DZ. Who uses the patient Internet portal? the PatientSite experience. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:91–95. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowles JB, Kind AC, Craft C, Kind EA, Mandel JL, Adlis S. Patients interest in reading their medical record: relation with clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and patients’ approach to health care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:793–800. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll AE, Zimmerman FJ, Rivara FP, Ebel BE, Christakis DA. Perceptions about computers and the Internet in a pediatric clinic population. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5:122–126. doi: 10.1367/A04-114R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MyGroupHealth (GroupHealth Cooperative) [(accessed July 13, 2005)]. www.ghc.org.

- 10.Patient Gateway (Partners Healthcare) [(accessed July 13, 2005)]. www.patientgateway.org.

- 11.Shared Care Plan (Whatcom County Pursuing Perfection Project) [(accessed July 13, 2005)]. www.sharedcareplan.org.

- 12.Bishop LS, Holmes BJ, Kelley CM. National consumer health privacy survey 2005. California Health Care Foundation; 2005. [(accessed March 14, 2006)]. Available from http://www.chcf.org/topics/view.cfm?itemID=115694.