Abstract

Clinical and preclinical evidence suggests that cocaine exposure hastens progression of the HIV disease process. An established active, euphoric dose of cocaine (20 mg/kg) was administered to SCID mice according to a regimen consistent with exposure to the drug by cocaine-abusing HIV-infected patients to determine the effects of cocaine on four previously established pathological characteristics of HIV encephalitis: cognitive deficits, fatigue, astrogliosis, and microgliosis. Mice were intracranially inoculated with either HIV-infected, or uninfected macrophages and then injected with either cocaine or saline in a 2(Infection) × 2(Cocaine) factorial design. Cognition was assessed by acquisition and retention of a spatially cued learning task. Fatigue was assessed by monitoring motor activity following a 2 minute forced swim. Mice were then sacrificed to determine the extent of astrogliosis and microgliosis in the four groups. Results indicated that in comparison to uninfected controls, HIV positive mice had increased astrogliosis and microgliosis, cognitive deficits, and recovered more slowly from fatigue. However, despite evidence that the cocaine exposure regimen activated the central nervous system and had long-term CNS effects, the drug did not alter the behavioral or the neuropathological deficits noted in HIV-infected SCID mice.

Keywords: AIDS, Dementia, HIV -associated Dementia, Animal models, Drug Abuse

Introduction

Current estimates indicate that a high proportion of HIV-infected individuals abuse drugs (2004) such as cocaine. In addition to being an HIV infection risk factor (Mccoy et al., 2004), cocaine appears to detrimentally modify the HIV disease process (Goodkin et al., 1998). Further, cocaine directly influences the immune system as demonstrated by increases in TNF alpha and IL-6 production after cocaine exposure and excessive exposure to these pro-inflammatory cytokines could be detrimental to brain tissue [see Review (Tyor and Middaugh, 1999)]. Thus, in addition to reducing HIV medication compliance (Arnsten et al., 2002), these findings suggest that cocaine abuse is capable of accelerating HIV-associated complications.

HIV-associated dementia (HAD) occurs commonly in HIV infected patients (McArthur, 1990; McArthur et al., 1993) and is an AIDS defining illness. SCID mice, inoculated with HIV-infected macrophages, model many features of HAD such as gliosis and HIV-infected mononuclear phagocytes (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Persidsky et al., 1996; Tyor et al., 1993) as well as cognitive impairments (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Griffin et al., 2004). As such, the SCID mouse model of HIV encephalitis can help elucidate the interactive effects of cocaine and HIV on indexes of neuropathological damage and behavioral deficts (Tyor and Middaugh, 1999).

The primary objective of the present study was to examine the influence of chronic cocaine exposure in HIV-positive SCID mice on the behavioral measures, cognition and motor fatigue, and on the neuropathological features, astrogliosis and microgliosis. Because cocaine abuse was reported to exacerbate self-reported cognitive impairment in HIV seropositive patients (Avants et al., 1997), our hypothesis was that chronic cocaine exposure would exacerbate the cognitive impairment previously reported in HIV-infected SCID mice (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Griffin et al., 2004). In addition, we hypothesized that histopathological features of the HIV encephalitis (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Persidsky et al., 1996; Tyor et al., 1993) would also be worsened by chronic cocaine exposure.

Subjects

Male CB-17 SCID mice (4 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). They were singly housed in micro-isolator cages with free access to food and water for one week prior the experiment as previously described (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Griffin et al., 2004). All procedures were conducted in AAALAC-approved facilities, were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and were consistent with the guidelines of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23, revised 1996).

Mouse inoculation with HIV-infected and uninfected macrophages

Although there is evidence mice can be non-productively infected with HIV (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998a) to better approximate productive infection during HIV encephalitis, mice were inoculated with HIV-infected human macrophages. This xenograft endures 4-6 weeks (Tyor et al., 1993) and provides the opportunity to evaluate behavioral manifestations of HIV encephalitis. To control for the effects of human macrophages themselves, a separate group of mice were inoculated with uninfected macrophages. The cell culture and inoculation procedures for the current study were identical to recent reports (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Cook et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). Briefly, 108 purified primary human macrophages were cultured in the presence of monocyte colony stimulating factor (M-CSF). Half of the cells were infected with HIV-1ADA virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.2 viral particles per cell while the other half remained uninfected. After two weeks of culture, mice were inoculated with either 1 × 105 infected cells or with uninfected cells resuspended in 30 μL phosphate buffered saline. Cells were delivered over 25 seconds using a freehand injection into the right frontal lobe, behind the orbital sinus, using a syringe fitted with a collar to control depth to 4mm below the skull surface. The xenograft placement corresponds to plate 160 in the brain atlas by Sidman et. al. (Sidman et al., 1971). The procedure yields reproducible xenografts within and across experiments.

Experimental Procedure

The experiment was conducted over a 9-week period and consisted of 4 groups of mice distinguished by HIV status (i.e., whether the inoculated macrophages were HIV infected or not) and drug treatment (IP injections of Cocaine, 20 mg/kg or equivalent volumes of Saline Vehicle): HIV negative + Vehicle (NV), HIV negative + Cocaine (NC), HIV positive + Vehicle (PV) and HIV positive + Cocaine (PC). Vehicle (0.9% saline) or cocaine (20mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally at a volume of 0.01 ml/g bodyweight daily (∼1000hr) Monday through Friday during Weeks 1 through 5. Several mice were excluded from the final analysis based on inconclusive histopathological evidence of HIV infection (n=8). The final group sizes for the 2(HIV) × 2(Cocaine) factorial design were: NV (n=12), NC (n=11), PV (n=9), PC (n=8).

The cocaine exposure regimen was designed to provide drug exposure consistent with that of a cocaine abusing, HIV positive patient, with exposure beginning prior to HIV infection and continuing after HIV infection. Drug holidays were incorporated into the model to reflect the intermittent use suggested by studies on treatment seeking individuals [e.g. (Grabowski et al., 2000; Myrick et al., 2001a; Myrick et al., 2001b)]. Further, since humans abuse cocaine for its euphoric value (Dackis and O’Brien, 2001), an essential part of the model was to use a dose of cocaine that activates the central nervous system and is rewarding for mice.

Cocaine effects on motor activity of SCID mice

To select a cocaine dose for the primary study, locomotor activity was assessed over a 60-min time period following IP injections of 0, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg/kg doses of cocaine in SCID mice (n=6 per dose) using a previously described procedure (Griffin et al., 2004). Cocaine induced seizures at the two highest doses and death for most of the mice injected with the 40 mg/kg dose. The two lower doses did not induce seizures but increased activity above vehicle levels; 55% for the 10 mg/kg dose and 61% for the 20 mg/kg dose. The 20 mg/kg dose was selected for further study because: 1) in addition to its CNS activation for the SCID mice, it stimulates activity in several mouse strains (Griffin and Middaugh, 2006; Kuzmin et al., 2000; Tolliver and Carney, 1994), 2) there is solid evidence of its hedonic value in mice using place conditioning studies (Szumlinski et al., 2004; Szumlinski et al., 2002) and self-administration experiments (Griffin and Middaugh, 2003), and 3) the larger peak concentrations following i.p. injection of 20 mg/kg would prolong the xenograft’s exposure to cocaine, an important consideration given cocaine’s half life of 11 to 22 minutes in mice (Azar et al, 1998; Benuck et al, 1987; Reith et al, 1987).

Cocaine exposure did not alter locomotor activity in HIV-positive mice challenged with cocaine

Motor activity of the four groups of mice defined by inoculation with either the HIV-infected, or uninfected macrophages, and whether injections were saline or cocaine (20 mg/kg) was assessed at weekly intervals, two prior to (i.e., Weeks 1 & 2), and two after inoculation (Weeks 3 & 5). Activity assessed on Week-1 indicated that the first exposure to cocaine increased activity approximately 74% over that of vehicle treated controls. The second activity test on Week 2 (i.e., after 7 daily vehicle or cocaine injections) indicated approximately 45% elevated activity for cocaine compared to vehicle-injected mice. A 2(Cocaine Dose) × 2 (Week) ANOVA provided statistical confirmation that cocaine stimulated motor activity of SCID mice [F(1,36)= 16.8, p< 0.001] prior to their inoculation with HIV infected or uninfected macrophages.

After inoculation with either HIV-infected or uninfected macrophages, cocaine continued to stimulate motor activity with the degree of stimulation greater for the third test one week after inoculation (40% increase) than the fourth test two weeks after inoculation (16% increase). A significant Dose × Week interaction term [Dose × Week: F(1,36)= 4.6, p= 0.038] from a 2(Infection) × 2(Dose) × 2(Session) ANOVA provided statistical support for the cocaine effect. The analysis provided no statistical support for HIV infection impacting motor activity or interacting with cocaine stimulation [all p values greater than 0.379]. The consistent elevated activity for cocaine-injected mice substantiate the biological activity of cocaine dose used in the study; however, cocaine did not interact with HIV infection to impact activity.

Cocaine exposure did not exacerbate the learning impairment produced by HIV infection

After completion of the locomotor activity tests, mice were re-inoculated (4 weeks after the first inoculation) with fresh macrophages according to their original group designation. Cognitive behavior was assessed by determining the acquisition (learning) and retention (memory) of a spatially cued task in a Morris Water Maze equipped with a Polytrack animal tracking system (San Diego Instruments, Inc, San Diego, CA) as previously described (Griffin et al., 2004).

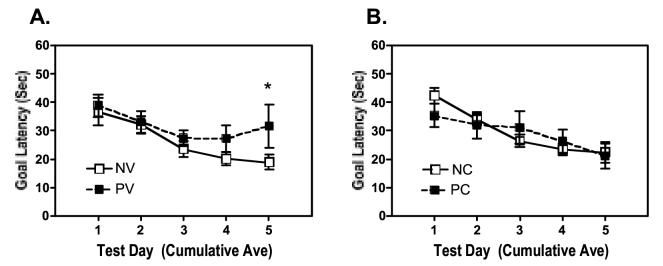

Fig. 1 summarizes the times (goal latencies) to reach the submerged goal platform based on running two-day-averages across six acquisition sessions. Latencies declined across sessions for all four groups, indicating learning of the spatially cued task. A 2(Infection) × 2(Dose) × 2(Session) ANOVA on data collected on the initial vs the last two-day average confirmed a significant reduction in latency across the sessions [Session: F(1,35) = 44.182, p = 0.001]. Analysis of data within each group across session indicated significant reductions in latency for all groups except mice inoculated with infected macrophages (PV) [PV: t(8)= 1.202, p> 0.2; NV: t(11)= 5.087, p< 0.001; PC: t(6)= 2.418, p= 0.052; NC: t(10= 7/219, p< 0.001]. These results indicate that the acquisition of the spatially cued learning problem was significantly impaired for HIV inoculated mice; however, contrary to our hypothesis, cocaine attenuated, rather than exacerbated this impairment. Finally, neither HIV status nor history of cocaine exposure influenced the swimming ability or visual acuity of the mice as indicated by their ability to locate a visible platform in the water maze using previously described procedures (Griffin et al., 2004). A 2 (Infection) × 2 (Dose) ANOVA indicated no significant effects of Infection, Dose, (both F(1,38)<1.5), or the interaction of the factors (F(1,38)<1). Thus, the HIV-induced reduction in acquisition of the learning task was not confounded by impaired motor function or visual ability.

Figure 1.

Learning the water maze task. Goal latencies from Day 1 to Day 6 during the acquisition phase of the Morris Maze experiment were reduced, indicative of mice learning the location of the submerged platform. HIV-positive mice had longer goal latencies on Day 6 (*p<0.05). A history of cocaine exposure did not affect the ability to learn the maze task (p>0.1). [n=8-12 per group: NV, HIV negative macrophages vehicle treated; NC, HIV negative macrophages, cocaine treated; PV, HIV positive macrophages, vehicle treated; PC, HIV positive cocaine treated]

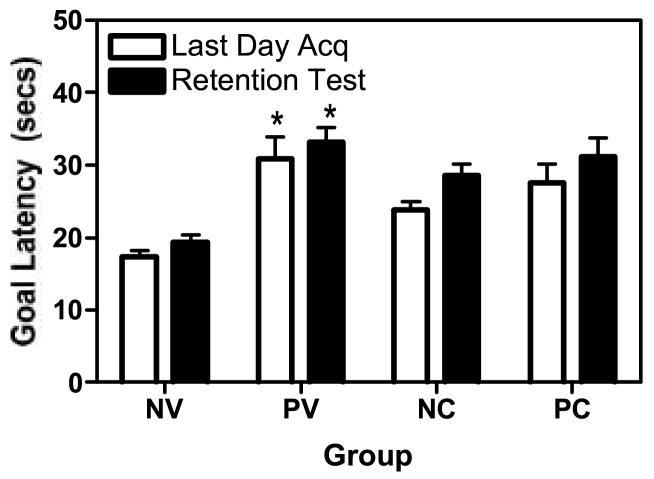

Memory (retention) of the spatially cued problem was not effected by HIV status, cocaine exposure or their interaction

Fig. 2 summarizes the goal latencies during the final acquisition and the retention tests. A 2(Infection) × 2 (Drug) × 2 (Day-6 vs Retention Session) ANOVA established that latencies during the last acquisition day vs the retention test did not differ significantly indicating that memory for the spatially cued learning task was maintained during the 7 day hiatus [F(1,55) < 1]. Importantly, neither HIV nor Cocaine treatments impacted the memory measure [F-values for all interaction terms < 1]. Consistent with the acquisition data, performance continued to be impaired for HIV infected mice [F(1,35)= 4.567, p= 0.04] due to the original learning deficit.

Figure 2.

Memory in the water maze task. Goal latencies did not change as a result of the hiatus between day 6 and the retention test. However, the goal latencies were longer in the HIV positive, vehicle treated mice compared to the NV group (*p<0.05) on day 6 and the retention test, consistent with spatial memory deficits. A history of cocaine exposure did not exacerbate the effects of HIV. See Figure 1 for legend information.

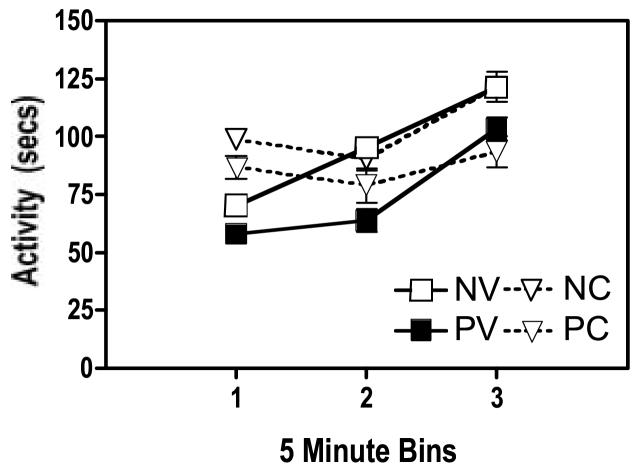

HIV infection retarded recovery from fatigue induced by forced swimming

After completing the water maze retention test, the mice were forced to swim continuously for 2 minutes, and locomotor activity was immediately assessed over a 15-minute period to provide a measure of fatigue. Fig. 3 summarizes motor activity for the 4 groups. Data were log transformed for analysis with a 2(Infection) × 2 (Cocaine) × 3(Time Interval) ANOVA. Activity increased across the measurement period [Time Interval: F (2,72) = 34, p <0.0001], suggesting a recovery from the fatigue generated by the forced swim. Further, activity was lower for HIV-infected than for uninfected mice [Infection: F (1, 36) = 4.9, p = 0.0332]. This reduction in recovery from the swim-induced fatigue confirms a previous report for HIV inoculated SCID mice (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b). The impaired recovery from fatigue was also noted in a second study (Griffin et al., 2004), albeit the effect was not statistically supported because of the reduced power associated with the small group sizes used. These data indicate that physical challenges, such as the 2-min forced swim test, reveal deficits in HIV-infected mice, perhaps related to increased fatigue or reduced physical endurance.

Figure 3.

Activity after 2 minutes of forced swimming. Activity was reduced in HIV positive mice (p<0.05), regardless of cocaine history, indicating that physical exertion of long duration reveals locomotor deficits in HIV positive mice. Further, in the absence of cocaine, activity was elevated during the first time bin in mice with a history of cocaine exposure (p<0.05), providing more evidence that the dose of cocaine was biologically active in these mice and produced enduring neurobiological effects. See Figure 1 for legend information.

Neurobiological changes associated with the cocaine exposure were long lasting

As noted in Fig. 3, motor activity appeared to be elevated for the two groups of mice previously exposed to cocaine, although they were cocaine free during this test. [Cocaine × Test Interval interaction: F (2, 72) = 5.47, p=0.0061]. Post hoc analysis to resolve this interaction indicated that the mice with a history of cocaine exposure in the activity monitor were more active than vehicle treated mice during the first 5-min time bin (t=-2.019, df 39, p<0.05). This finding is consistent with several reports of conditioned hyper-locomotion of mice exposed to cocaine in a particular environment (Michel et al., 2003; Michel and Tirelli, 2002; Tirelli et al., 2005). Importantly, this finding indicates that the cocaine regimen used in our experiment produced enduring biological alterations in the central nervous system of the SCID mice.

Innoculation of HIV infected or uninfected macrophages produced the expected neuropathology

One day after the forced swim test, mice were sacrificed and their brains extracted. After snap freezing, brains were sectioned at 5 microns and the tissue sections were stained according to our previously published protocols (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Cook et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). The neuropathology was evaluated by WRT who was blinded to the animals’ treatment history. Pathological analysis revealed the presence of human macrophages (EBM/11; DAKO; 1:50), p24+ human macrophages (DAKO; 1:50), and multinucleated giant cells in HIV-infected mice as previously reported (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Cook et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). Brains of mice inoculated with uninfected cells also showed presence of human macrophages (p24 negative); however, in comparison to the HIV-infected group, fewer multinucleated giant cells were observed. Although seen in greatest quantity around the injection track, these cells frequently spread to adjacent brain parenchyma as previously reported (Avgeropoulos et al., 1998b; Cook et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). Finally, as expected, the numbers of HIV-infected cells (positive for p24 staining) were equivalent for cocaine treated vs vehicle HIV-infected mice indicating that the numbers of cells in the xenografts were similar.

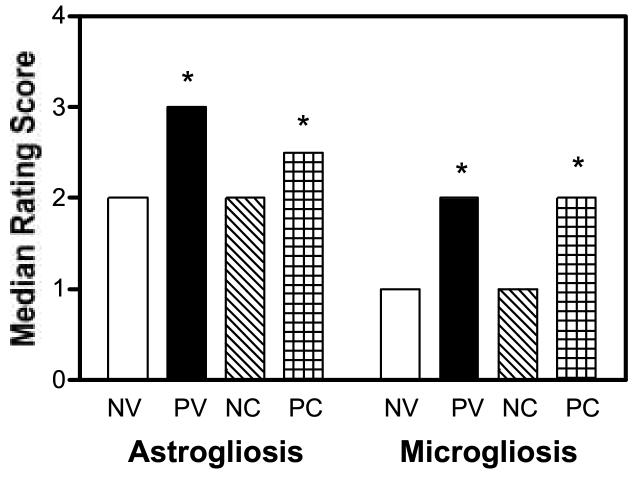

Cocaine exposure did not exacerbate the astrogliosis and microgliosis produced by HIV

Astrogliosis (anti-GFAP; Chemicon; 1:750) and microgliosis (F4/80; Caltag; 1:20) were graded according to a 4-point scale (Cook et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). The section with the highest score from each mouse was used for the data summarized in Fig. 4. Astrogliosis ratings were analyzed with a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis One way ANOVA appropriate for ordinal rating scales and indicated significant group differences [χ2 =12.0892, df=3, p=0.0071]. Post-hoc comparisons of selected groups with Mann Whitney U Tests indicated that astrogliosis ratings for PV mice were significantly elevated compared to NV mice (p=0.001) and tended to be elevated in the PC compared to the NC mice (p=0.0684) indicating that HIV infection produced astrogliosis. In contrast, cocaine did not produce astrogliosis [NV compared to NC mice (p=0.39); PV compared to PC mice (p=0.49). Microgliosis ratings were also greater for mice inoculated with HIV-infected macrophages compared to those for mice inoculated with uninfected cells [Group Effect: χ2 =9.9381, df=3, p=0.0191]. As noted for astrogliosis, post-hoc comparisons indicated that microgliosis scores were significantly greater for the PV compared to NV mice (p=0.0193) and for PC compared to the NC mice (p=0.0221) indicating HIV induced microgliosis. Also consistent with the astrogliosis ratings, cocaine did not impact microgliosis [NV compared to NC mice (p=0.11); PV compared to PC mice (p=0.25)]. Thus, although HIV increased astrogliosis and microgliosis as previously reported (Griffin et al, 2004), neither was exacerbated by the CNS active dose of cocaine used in our study.

Figure 4.

Astrogliosis and microgliosis ratings. HIV positive mice had greater astrogliosis and microgliosis scores than HIV negative mice (*p<0.05). However, a history of cocaine exposure did not exacerbate these findings. See Figure 1 for legend information

Discussion

Cocaine did not exacerbate the HIV pathology assessed in the current study despite using a hedonically relevant cocaine dose with demonstrated behavioral activity, and a dosing procedure initiated one week prior to and extending 4 weeks after HIV infection that produced long-term CNS changes as established by conditioned stimulation,. The absence of a cocaine effect on HIV-induced cognitive deficits, fatigue and neuropathology remain speculative. Certainly different cocaine doses and exposure patterns might alter the progression HIV-related dysfunction. For example, in vitro experiments suggest that HIV replication is maximally stimulated by 24 hours of exposure to nanomolar cocaine concentrations and normalizes to control levels at higher concentrations (Peterson et al., 1991; Peterson et al., 1992). A similar increased HIV replication, as well as altered immune cell populations in peripheral tissues, was reported following a 5 mg/kg dose of cocaine in SCID mice (Roth et al., 2002; Roth et al., 2005). Although these reports suggest that cocaine doses lower than the 20 mg/kg dose used in the present experiment might enhance HIVE parameters, whether these lower doses are relevant to the drug’s rewarding/reinforcing effects in SCID mice is unknown. Additional experiments using alternative dosing conditions, and perhaps different HIV infection procedures are necessary to fully assess possible interactive effects of cocaine and HIV neuropathology.

In conclusion, using the SCID mouse model of HIV encephalitis, we established that HIV positive mice were cognitively impaired, had reduced recovery from fatigue induced by forced swim challenge and had increased astrogliosis and microgliosis in comparison to uninfected control mice. Further, cocaine exposure according to a procedure which was biologically relevant and produced long-term CNS effects on SCID mice, and which has demonstrated reward value for other mouse strains, did not exacerbate the HIVE pathology. Although more studies are needed to investigate the potential interactive effects of cocaine and HIV using in vivo models of HIV infection, the present study suggests that substantial exposure to rewarding doses of cocaine is not a sufficient condition to exacerbate a number of the characteristics of HIV encephalitis.

Acknowledgements

WCG was supported by T32 DA07288. WRT and LDM were supported by NIDA RO1 DA11870. The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Irfan Khan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants SK, Margolin A, McMahon TJ, Kosten TR. Association between self-report of cognitive impairment, HIV status, and cocaine use in a sample of cocaine-dependent methadone-maintained patients. Addict Behav. 1997;22:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgeropoulos N, Burris G, Ohlandt G, Wesselingh S, Markham RB, Tyor W. Potential Relationships Between the Presence of HIV, Macrophages, and Astrogliosis in SCID Mice with HIV Encephalitis. Journal of Neuro-AIDS. 1998a;2:1–20. doi: 10.1300/J128v02n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgeropoulos N, Kelley B, Middaugh L, Arrigo S, Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE, Tyor WR. SCID mice with HIV encephalitis develop behavioral abnormalities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998b;18:13–20. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199805010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Dasgupta S, Middaugh LD, Terry EC, Gorry PR, Wesselingh SL, Tyor WR. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:795–803. doi: 10.1002/ana.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, O’Brien CP. Cocaine dependence: a disease of the brain’s reward centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin K, Shapshak P, Metsch LR, McCoy CB, Crandall KA, Kumar M, Fujimura RK, McCoy V, Zhang BT, Reyblat S, Xin KQ, Kumar AM. Cocaine abuse and HIV-1 infection: epidemiology and neuropathogenesis. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:88–101. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Silverman P, Schmitz JM, Stotts A, Creson D, Bailey R. Risperidone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:305–310. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, 3rd, Middaugh LD. Acquisition of lever pressing for cocaine in C57BL/6 mice: Effects of prior Pavlovian conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, 3rd, Middaugh LD, Cook JE, Tyor WR. The severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis: Deficits in cognitive function. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:109–115. doi: 10.1080/13550280490428333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, 3rd, Middaugh LD. The influence of sex on extracellular dopamine and locomotor activity in C57BL/6J mice before and after acute cocaine challenge. Synapse. 2006;59:74–81. doi: 10.1002/syn.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin A, Johansson B, Fredholm BB, Ogren SO. Genetic evidence that cocaine and caffeine stimulate locomotion in mice via different mechanisms. Life Sci. 2000;66:PL113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur J. Neurologic disease associated with HIV-1 infection. In: Johnson RT, editor. Current Therapy in Neurologic Disease-3. Decker: 1990. pp. 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Hoover DR, Bacellar H, Miller EN, Cohen BA, Becker JT, Graham NM, McArthur JH, Selnes OA, Jacobson LP. Dementia in AIDS patients: incidence and risk factors. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Neurology. 1993;43:2245–2252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, Messiah SE, Zhao W. Injection Drug Use and Crack Cocaine Smoking: Independent and Dual Risk Behaviors for HIV Infection. AEP. 2004;14:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A, Tirelli E. Post-sensitisation conditioned hyperlocomotion induced by cocaine is augmented as a function of dose in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;132:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A, Tambour S, Tirelli E. The magnitude and the extinction duration of the cocaine-induced conditioned locomotion-activated response are related to the number of cocaine injections paired with the testing context in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;145:113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, Henderson S, Brady KT, Malcolm R. Gabapentin in the treatment of cocaine dependence: a case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001a;62:19–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, Henderson S, Brady KT, Malcom R, Measom M. Divalproex loading in the treatment of cocaine dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001b;33:283–287. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Limoges J, McComb R, Bock P, Baldwin T, Tyor W, Patil A, Nottet HS, Epstein L, Gelbard H, Flanagan E, Reinhard J, Pirruccello SJ, Gendelman HE. Human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in SCID mice. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1027–1053. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PK, Gekker G, Chao CC, Schut R, Molitor TW, Balfour HH., Jr. Cocaine potentiates HIV-1 replication in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cocultures. Involvement of transforming growth factor-beta. J Immunol. 1991;146:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PK, Gekker G, Chao CC, Schut R, Verhoef J, Edelman CK, Erice A, Balfour HH., Jr. Cocaine amplifies HIV-1 replication in cytomegalovirus-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cell cocultures. J Immunol. 1992;149:676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MD, Tashkin DP, Choi R, Jamieson BD, Zack JA, Baldwin GC. Cocaine enhances human immunodeficiency virus replication in a model of severe combined immunodeficient mice implanted with human peripheral blood leukocytes. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:701–705. doi: 10.1086/339012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MD, Whittaker KM, Choi R, Tashkin DP, Baldwin GC. Cocaine and sigma-1 receptors modulate HIV infection, chemokine receptors, and the HPA axis in the huPBL-SCID model. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1198–1203. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Angevine JB, Pierce ET. Atlas of the Mouse Brain and Spinal Cord. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Price KL, Frys KA, Middaugh LD. Unconditioned and conditioned factors contribute to the ‘reinstatement’ of cocaine place conditioning following extinction in C57BL/6 mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136(1):151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Dehoff MH, Kang SH, Frys KA, Lominac KD, Klugmann M, Rohrer J, Griffin W, 3rd, Toda S, Champtiaux NP, Berry T, Tu JC, Shealy SE, During MJ, Middaugh LD, Worley PF, Kalivas PW. Homer proteins regulate sensitivity to cocaine. Neuron. 2004;43:401–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli E, Michel A, Brabant C. Cocaine-conditioned activity persists for a longer time than cocaine-sensitized activity in mice: implications for the theories using Pavlovian excitatory conditioning to explain the context-specificity of sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2005;165:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolliver BK, Carney JM. Comparison of cocaine and GBR 12935: effects on locomotor activity and stereotypy in two inbred mouse strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:733–739. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR, Power C, Gendelman HE, Markham RB. A model of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in scid mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8658–8662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR, Middaugh LD. Do alcohol and cocaine abuse alter the course of HIV-associated dementia complex? J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65(4):475–481. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]