Abstract

BACKGROUND

There are conflicting assumptions regarding how patients’ preferences for life-sustaining treatment change over the course of serious illness.

OBJECTIVE

To examine changes in treatment preferences over time.

DESIGN

Longitudinal cohort study with 2-year follow-up.

PARTICIPANTS

Two hundred twenty-six community-dwelling persons age ≥60 years with advanced cancer, congestive heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

MEASUREMENTS

Participants were asked, if faced with an illness exacerbation that would be fatal if untreated, whether they would: a) undergo high-burden treatment at a given likelihood of death and b) undergo low-burden treatment at a given likelihood of severe disability, versus a return to current health.

RESULTS

There was little change in the overall proportions of participants who would undergo therapy at a given likelihood of death or disability from first to final interview. Diversity within the population regarding the highest likelihood of death or disability at which the individual would undergo therapy remained substantial over time. Despite a small magnitude of change, the odds of participants’ willingness to undergo high-burden therapy at a given likelihood of death and to undergo low-burden therapy at a given likelihood of severe cognitive disability decreased significantly over time. Greater functional disability, poorer quality of life, and lower self-rated life expectancy were associated with decreased willingness to undergo therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

Diversity among older persons with advanced illness regarding treatment preferences persists over time. Although the magnitude of change is small, there is a decreased willingness to undergo highly burdensome therapy or to risk severe disability in order to avoid death over time and with declining health status.

KEY WORDS: life support care, decision-making, chronic disease

INTRODUCTION

There are two prevailing but contradictory assumptions regarding changes in the treatment preferences of seriously ill older persons, and these assumptions have different implications for the provision of end-of-life care. The first of these posits that, as patients become more ill, they value quality over quantity of life, such that their preferences are best met by earlier enrollment in hospice care.1,2 The second of these assumptions is that as patients get closer to death, they are more willing to endure the burden of therapies for the chance of prolonging life,3 and therefore desire ongoing access to intensive interventions.

Conflicting data support both of these assumptions. Although several studies have found that the desire to receive life-sustaining treatment increases with declining health and/or psychological status,4,5 several have found no association between preferences and health status,6–8 while others have found an association between declining health status and decreasing desire for life-sustaining therapy.9,10 These studies all share the approach of assessing patients’ preferences for interventions, without specifying their possible outcomes. Patients’ preferences, however, are heavily dependent on these outcomes.11,12 Moreover, when these outcomes are not explicitly identified, patients may make incorrect assumptions about what the outcomes are, and they may change their preferences when their misconceptions are corrected.13

In an earlier study among a cohort of older persons with advanced illness, we demonstrated that the acceptability of certain treatment outcomes, described in terms of different health states, changed over time and in association with participants’ own health.14 Although this assessment of preferences explicitly considered outcomes, it simplified the assessment by not including trade-offs between treatment burden and outcome and not including uncertainty, additional factors that have been shown to influence preferences.12 The purpose of the current study was to examine changes in preferences over time among this same cohort by assessing participants’ willingness to risk the high treatment burden or adverse outcomes of potentially life-prolonging therapy.

METHODS

Participants

Participants for this study were 226 community-dwelling older persons with advanced chronic illness. The Human Investigations Committee of each of the hospitals participating in the study approved the study protocol, and each participant provided written informed consent. We screened sequential charts of persons aged 60 years or older with a primary diagnosis of cancer, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for the primary eligibility requirement: advanced illness, as defined by Connecticut Hospice15 or SUPPORT16 criteria. Charts were identified according to the patient’s age and primary diagnosis in subspecialty outpatient practices and three hospitals, including the VA, in the greater New Haven area. Of 26 practices approached for participation, 3 (12%) did not permit chart screening. An additional eligibility criterion was the need for assistance with at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL)17 because this has been shown to provide additional prognostic information.18 Screening and enrollment was stratified by diagnosis to enroll approximately equal numbers of patients with the three diagnoses.

Of 548 patients identified by chart review, we were able to screen 470 by telephone to determine need for IADL assistance and additional exclusion criteria. Exclusion of 108 patients who were independent in IADLs; of 77 who had cognitive impairment, as assessed by the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire19 and EXIT;20 and of 6 with part-time Connecticut residence left 279 eligible participants. Of these, 2 died before and 51 refused participation. Nonparticipants did not differ from participants according to age or gender. Among eligible patients with heart failure, 8% refused participation, compared to 19% among patients with cancer and 25% among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P = .02).

Of the 226 initial participants, 8 withdrew after the initial interview (4%). Of the surviving 124 participants at the end of the first year, 98 (79%) consented to a second year of participation, without further withdrawals. Among those completing the study, ascertainment of data was 90% complete, and, among the 10% of missing data, 89% was due to the participant being too cognitively impaired or too ill to participate in the interview.

Data Collection

Nurse interviewers performed face-to-face interviews with patients in their homes at least every 4 months for up to 2 years. If the patient had a decline in health status, determined by a monthly telephone call, the next interview was scheduled immediately. The subsequent interview was conducted every 4 months, unless the patient had another decline. We defined decline in health status as: (1) a new disability, defined as requiring assistance from another person or being unable to perform, a basic activity of daily living (ADL),21 (2) a prolonged hospitalization (≥7 days) or a hospitalization resulting in a discharge to nursing home or rehabilitation facility, or (3) introduction of hospice services.

Descriptive and analytic variables included sociodemographic, health, and psychosocial status measures. Sociodemographic variables were obtained at the baseline assessment only; health and psychosocial measures were obtained at each interview. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender, ethnicity, education, sufficiency of monthly income,22 and marital status. Health status variables included self-rated health, ADL21 and IADL17 disability (each of 7 ADLs and IADLs scored as 0 for independent, 1 for requiring assistance, and 2 for unable to perform), self-rated life expectancy, and pain severity in the last 24 hours. Psychosocial variables included self-rated quality of life, depression, measured using the 2-item PRIME-MD,23 and whether the patient had a living will.

The outcome variables were patients’ treatment preferences assessed using the Willingness to Accept Life-Sustaining Treatment instrument (WALT).24 The WALT, building on a number of earlier instruments,25–27 was developed to assess treatment preferences through the explicit consideration of the trade-offs involved in the receipt of life-sustaining therapy. This approach was chosen because standard decision-analytic approaches to evaluate preferences are difficult for older persons to complete,28 demonstrate poor reliability,29 frequently lead to illogical responses,30,31 and may be particularly ill suited for the elicitation of preferences regarding life-sustaining treatment.32,33

Participants were asked to consider an exacerbation of their illness, which, if left untreated, would result in their death. In the first scenario, participants were asked to consider the trade-off of enduring high treatment burden for a given chance to avoid death. They were asked whether they would want high-burden therapy if it would return them to current health. Participants who would choose to have therapy were then asked whether they wanted therapy as the likelihood of death versus a return to current health increased. The second and third scenarios asked participants to consider the trade-off of risking a severely impaired health state in order to avoid death. Participants were asked whether they would want low-burden therapy resulting in either severe physical disability, described as being bedbound, or severe cognitive disability, described as not being aware of what is going on around you. Participants who would choose not to have therapy were then asked whether they would want therapy as the likelihood of return to current health versus disability increased.

Clinically meaningful likelihoods: 1, 10, 50, 90, and 99% chance of death or impaired health state were used. Pie charts were used to demonstrate these likelihoods to participants. For each scenario, we determined the highest likelihood of death, or physical or cognitive disability at which the participant would want to receive therapy (See the Appendix for the scenarios as presented to participants).

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the population. To provide a simple, unadjusted, population-level description of the magnitude of changes in preferences, we examined the distribution of responses to the 3 scenarios at the initial and final interviews. The final interview was the interview closest to death or dropout for those who did not complete 2 years of follow-up. Next, to determine whether ratings changed significantly over time and to determine factors associated with ratings, we utilized generalized linear mixed effects models,34,35 by implementing repeated measures continuation-ratio models with inclusion of a patient-level random effect.36 The resulting odds ratio is interpreted as the odds of desiring therapy at a given likelihood as compared to a lower likelihood of death or disability. We developed separate multivariable models for each of the 3 scenarios. Independent variables were eligible for inclusion in each of the multivariable models if they demonstrated a bivariate association with the outcome at P < .20. To be included in the final model, the variable needed to maintain P < .10. In each model, we included time, age, gender, race, and marital status regardless of bivariate associations. Time was measured in months. These analyses were carried out using SAS software (version 9.1), using Proc NLMIXED.37

RESULTS

Patient Population

Table 1 provides a description of the 226 participants. During the 2 years of follow-up, 77% of patients with cancer, 43% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 46% of patients with heart failure died. Of the cohort, 68% had at least 3 interviews and 36% had 5 or more. The median number of interviews was 2 for patients with cancer, 4 for patients with heart failure, and 5 for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 1.

Description of 226 Participants at Baseline

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis (%) | |

| Cancer | 35 |

| COPD | 36 |

| CHF | 29 |

| Age (years ± SD) | 73 ± 7 |

| Education (years ± SD) | 12 ± 3 |

| Race (%) | |

| White | 91 |

| African–American | 7 |

| Other | 2 |

| Women (%) | 43 |

| Married (%) | 58 |

| Has a living will (%) | 53 |

| Self-rated health: excellent/very good/good (%) | 36 |

| Self-rated quality of life: best possible/good (%) | 64 |

| Depressed (%) | 47 |

| Moderate/severe pain (%) | 27 |

| ≥2 hospitalizations in past year (%) | 47 |

| Intensive care unit admission in past year (%) | 34 |

| Self-rated life expectancy (%) | |

| <2 years | 15 |

| ≥2 years | 41 |

| Uncertain | 44 |

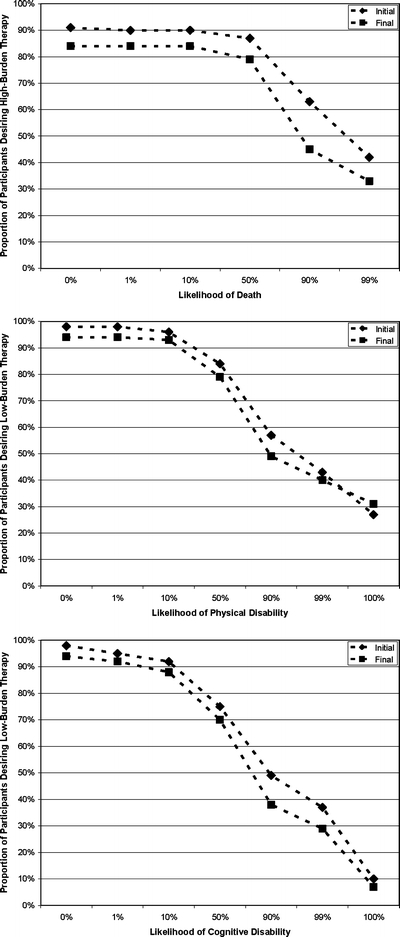

Initial and Final Preferences

Comparing the distribution of responses at the first and final interviews, there was a small decline in the overall proportions of participants willing to undergo therapy at a given likelihood of an adverse outcome in each of the 3 scenarios (Fig. 1). At both the initial and final interview, there was substantial variability within the population regarding participants’ willingness to undergo therapy. Even at the final interview, 33% were willing to undergo high-burden therapy despite a 99% chance of death. However, 14% were unwilling to undergo high-burden therapy even with a 0% chance of death. Whereas 31% were willing to undergo low-burden therapy resulting in severe physical disability at their final interview, only 7% were willing to undergo low-burden therapy resulting in severe cognitive disability.

Figure 1.

Proportion of participants who were willing to undergo either low- or high-burden therapy at a given likelihood of adverse outcome versus a return to current health. The diamonds represent participants’ responses at the initial interview, and the squares represent participants’ responses at the final interview.

Factors Associated with Changes in Preference

The results of longitudinal models were consistent with the descriptive results, with small but significant changes in participants’ preferences over time. The odds of participants’ willingness to undergo high-burden therapy at a given likelihood of death declined by 6% (95% CI 4%–8%) for each month of observation, demonstrating that participants became less willing to endure the burden of therapy in order to avoid death (Table 2). The odds of participants’ willingness to undergo low-burden therapy at a given likelihood of severe cognitive disability declined by 3% (CI 1%–5%) for each month of observation, demonstrating that participants became less willing to risk cognitive disability to avoid death. Although there was a trend toward a decline in the odds of participants’ willingness to accept low-burden therapy at a given likelihood of severe physical disability over time, this did not reach statistical significance

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Greater willingness to Undergo Therapy (i.e. Willing to Undergo Therapy at Higher Likelihoods of Adverse Outcome)

| Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to undergo high-burden therapy to avoid risk of death | Willingness to risk physical disability to avoid death | Willingness to risk cognitive disability to avoid death | |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

| Time in months | 0.94 (0.92, 0.96) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) |

| Age | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Female gender | 0.52 (0.28, 0.96) | 1.00 (0.64, 1.56) | 0.72 (0.46, 1.12) |

| Nonwhite | 2.18 (0.70, 6.77) | 2.66 (1.15, 6.12) | 3.21 (1.43, 7.18) |

| Married | 1.44 (0.77, 2.71) | 1.77 (1.12, 2.78) | 1.64 (1.04, 2.56) |

| Income just enough or not enough | 0.38 (0.21, 0.70) | 0.52 (0.34, 0.80) | – |

| Greater ADL disability | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | – | – |

| Greater IADL disability | – | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) | – |

| Self-rated life expectancy | |||

| ≥2 years | Reference | – | Reference |

| <2 years | 0.88 (0.49, 1.56) | 0.39 (0.25, 0.64) | |

| Uncertain | 1.70 (1.11, 2.60) | 0.97 (0.70, 1.36) | |

| Possesses living will | 0.44 (0.26, 0.72) | 0.50 (0.34, 0.73) | 0.50 (0.34, 0.74) |

| Fair/poor/worst quality of life | – | 0.65 (0.48, 0.88) | 0.70 (0.52, 0.95) |

ADL Activities of daily living, IADL instrumental activities of daily living

Worsening in several measures of health and psychosocial status was associated with decreased willingness to endure high-burden therapy and/or risk adverse outcome to avoid death (Table 2). Decline in ADL status was associated with decreased willingness to endure high-burden therapy, and worsening quality of life was associated with decreased willingness to risk severe physical or cognitive disability. Compared with those who believed their life expectancy was longer, participants who believed their life expectancy was <2 years were less willing to risk cognitive disability.

One measure of worsening health status, decline in IADLs, was associated with an increased willingness to risk disability to avoid death. Three measures of health status, diagnosis, pain, and depression, were not associated with preferences, nor was diagnosis associated with any of the outcomes we examined.

Compared to men, women were less willing to undergo high-burden therapy to avoid death. Nonwhite and married participants were more willing to risk physical and cognitive disability as compared to white and unmarried participants. Participants who reported having just enough or not enough money at the end of the month were less willing to undergo high-burden therapy and to risk physical disability to avoid death compared to those who had more than enough

DISCUSSION

In this study of seriously ill older persons followed for up to 2 years, we assessed how participants weighed the burden of therapy against the desire to avoid death by asking them whether, faced with an exacerbation of their illness that would be fatal if left untreated, they would undergo high-burden therapy at increasing likelihoods of death versus a return to their current health. We also assessed how they weighed the desire to avoid adverse functional outcomes against the desire to avoid death by asking them whether they would undergo low-burden therapy at increasing likelihoods of severe physical or cognitive disability versus a return to their current health.

The magnitude of change in the overall proportions of participants who would accept high-burden therapy at a given risk of death and low-burden therapy at a given risk of disability was small. Even at their final interview, large proportions remained willing to accept high-burden therapy despite a high likelihood of death. Despite its small magnitude, the change over time was significant. Participants became less willing to endure a high burden of therapy and less willing to risk severe cognitive disability to avoid death. In addition, several indicators of worsening health status, including greater ADL disability, and lower self-rated life expectancy and quality of life, were associated with decreased willingness to endure high-burden treatment and to risk disability.

The results of this study lend support to both prevailing assumptions regarding the preferences of seriously ill older persons. Patients’ decreasing willingness over time and with worsening health state to accept the burdens of therapy and risk of disability to avoid death supports the notion that, with advancing illness, patients value quality over quantity of life. In contrast, the large proportions of patients who desired high-burden therapy even with a high likelihood of death at their final interview supports the notion that some patients maintain a great willingness to undergo invasive therapies for even a small chance of returning to their current health. Moreover, the increased willingness to risk physical disability associated with declining IADL status suggest that declines in some domains of health may be associated with changes in how patients evaluate quality of life, with an increased acceptance of certain diminished health states.38,39

The results of this study confirm our earlier findings in this cohort, assessing attitudes toward different health states resulting from treatment, that cognitive disability becomes less acceptable over time and that, for patients experiencing a decline in their own physical functioning, physical disability becomes more acceptable.14 Unlike the earlier study, however, which showed that physical disability became more acceptable in the population as a whole, this study suggested that patients became less willing to risk physical disability. Because the current study assessed attitudes toward health states under conditions of uncertainty, which is a strong determinant of preferences,40 the differences in the two studies may be a reflection of increasing risk aversion over time.

The most important finding of the study may be the persistence in the diversity in preferences over time. This diversity highlights the danger in making assumptions about the preferences of older persons with advanced illness. Taken together with the changes in preferences over time, these results demonstrate the need to elicit individual preferences and to reexamine these preferences over the course of a patient’s illness. Furthermore, to provide care that is respectful of patients’ preferences, systems of end-of-life care must be able to provide a range of services, incorporating both palliative and life-sustaining therapies and tailored to the individual patient.41

This study also demonstrated that preferences differed according to sociodemographic characteristics. The large majority of nonwhite participants were African–American, and the association between nonwhite race and increased willingness to risk disability is consistent with literature showing that African–Americans are generally more willing than whites to undergo intensive therapies.42–44 The decreased willingness of participants reporting lower incomes to undergo high-burden therapy or risk physical disability to avoid death raises the question of whether they were concerned about financial burden. Although relieving emotional and caregiving burden on loved ones is a central concern for persons at the end of life,45–47 less is known about whether patients’ treatment decisions are influenced by financial considerations. Completion of a living will was also associated with a decreased willingness to risk adverse outcomes. Because of their vague language, living wills frequently cannot be applied to specific clinical situations.48 These results suggest that their completion may serve as a marker for patients’ desire to limit care to decrease burden and avoid disability, and should serve as a prompt for a more detailed discussion of patients’ preferences.

Because the study examined the preferences of patients with advanced illness, missing data are unavoidable. The largest cause of missing data in the study was mortality. It is unclear if these data are “missing” in the sense that this term is traditionally used because these data, along with the data from participants who became cognitively impaired or more severely ill, are not meaningful.49 However, there were also missing data from participants who dropped out of the study for other reasons or who failed to consent to a second year of participation and, therefore, we cannot know whether these missing data introduce bias into the results. Nonetheless, the high overall rates of participation and completeness of data collection among patients who remained in the study suggest that data collection was as complete as possible in this challenging population. Because the study population was predominantly white, the generalizability of the findings is limited.

Over time, seriously ill older persons retain great diversity in their willingness to endure burdensome therapy or risk severe disability to avoid death. Although the magnitude of change is small, this willingness decreases over time and with changes in health status. These findings call for the explicit elicitation of preferences and a highly individualized approach to the care of patients with advanced illness that has the flexibility to respond to changes in preferences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carm Joncas, R.N. and Barbara Mendes, R.N. for their interviewing skills.

This study was supported by grant PCC-98-070-1 from VA HSR&D, R01 AG19769 from the National Institute on Aging, P30 AG21342 from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale, and a Paul Beeson Physician Faculty Scholars Award. Dr. Fried is supported by K02 AG20113 from the National Institute on Aging.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest None disclosed

Appendix

Scenario 1

Think about if you were suddenly to get sick with an illness that would require you to be in the hospital for at least a month. It would either be that your [CHF, COPD, cancer] worsened, or you got sick with a different illness. In the hospital, you would need to have many minor tests, such as x-rays and blood draws, and you would require more tests, such as CT scans. You would need major therapies such as being in the intensive care unit, receiving surgery, or having a breathing machine. Without the treatment, you would not survive. If this treatment would get you back to your current state of health, would you want to have it?

If NO: Question complete.

If YES: Now, what if the doctor told you that there was a 50/50 chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health. If it did not work, you would not survive. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If NO: Now what if the doctor told you there were a 90% (99%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 10% (1%) chance that it would not. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If YES: Now, what if the doctor told you there was a 10% (1%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 90% (99%) chance that it would not work. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

Scenario 2

Think again about if you were suddenly to get sick with an illness that would require you to be in the hospital for a few days to a week. It would either be that your [CHF, COPD, cancer] worsened, or you got sick with a different illness. In the hospital, you would need to have minor tests, such as x-rays and blood draws, and therapies such as intravenous antibiotics and oxygen. However, this time, imagine that at the end of the treatment, you would be in a state where you would be bedbound. You would not be able to get up out of bed to the bathroom by yourself, and you would need help with all of your daily activities. Without the treatment, you would not survive. Would you want the treatment?

If YES: Question complete.

If NO: Now, what if the doctor told you that there was a 50/50 chance that it would get you back to your current state or would leave you bedbound. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If NO: Now what if the doctor told you there were a 90% (99%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 10% (1%) chance that it would leave you bedbound. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If YES: Now, what if the doctor told you there was a 10% (1%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 90% (99%) chance that it would leave you bedbound. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

Scenario 3

Think again about if you were suddenly to get sick with an illness that would require you to be in the hospital for a few days to a week. It would either be that your [CHF, COPD, cancer] worsened, or you got sick with a different illness. In the hospital, you would need to have minor tests, such as x-rays and blood draws, and therapies such as intravenous antibiotics and oxygen. Now imagine that the treatment would leave you in a state where your mind would not be working, such that you would not be aware of what was going on around you or be able to recognize your loved ones. Without the treatment, you would not survive. Would you want the treatment?

If YES: Question complete.

If NO: Now, what if the doctor told you that there was a 50/50 chance that it would get you back to your current state or would leave you unaware. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If NO: Now what if the doctor told you there were a 90% (99%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 10% (1%) chance that it would leave you unaware. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

If YES: Now, what if the doctor told you there was a 10% (1%) chance that it would work and get you back to your current state of health and a 90% (99%) chance that it would leave you unaware. Without the treatment, then you would not survive for certain. Would you want the treatment?

Footnotes

Presented in part at the national meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, May 11, 2005.

References

- 1.Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:172–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Meier DE, Morrison RS. Autonomy reconsidered. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1087–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Finucane TE. How gravely ill becomes dying: a key to end-of-life care. JAMA. 1999;282:1670–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Danis M, Garrett J, Harris R, Patrick DL. Stability of choices about life-sustaining treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:567–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Straton JB, Wang NY, Meoni LA, et al. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:577–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Everhart MA, Pearlman RA. Stability of patient preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments. Chest. 1990;97:159–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Silverstein MD, Stocking CB, Antel JP, Beckwith J, Roos RP, Siegler M. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and life-sustaining therapy: patients’ desires for information, participation in decision making, and life-sustaining therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:906–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Weissman JS, Haas JS, Fowler FJ, Jr., et al. The stability of preferences for life-sustaining care among persons with AIDS in the Boston Health Study. Med Decis Making. 1999;19:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ditto PH, Smucker WD, Danks JH, et al. Stability of older adults’ preferences for life-sustaining medical treatment. Health Psychol. 2003;22:605–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Phillips RS, et al. Factors associated with change in resuscitation preference of seriously ill patients. The SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1558–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Kagawa-Singer M. End-of-life decision making: a qualitative study of elderly individuals. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fried TR, Bradley EH. What matters to older seriously ill persons making treatment decisions? A qualitative study. J Pall Med. 2003;6:237–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:545–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.The Connecticut Hospice Inc. Summary Guidelines for Initiation of Advanced Care. Branford, CT: John Thompson Institute; 1996.

- 16.Murphy DJ, Knaus WA, Lynn J. Study population in SUPPORT: patients (as defined by disease categories and mortality projections), surrogates, and physicians. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:11S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed]

- 18.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF. Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1221–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR. Assessment of patient preferences: Integrating treatments and outcomes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:S348–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Danis M, Mutran E, Garrett JM, et al. A prospective study of the impact of patient preferences on life-sustaining treatment and hospital cost. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1811–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Pearlman RA, Cain KC, Patrick DL, et al. Insights pertaining to patient assessments of states worse than death. J Clin Ethics. 1993;4:33–41. [PubMed]

- 27.Dales RE, O’Connor A, Hebert P, Sullivan K, McKim D, Llewellyn-Thomas H. Intubation and mechanical ventilation for COPD: development of an instrument to elicit patient preferences. Chest. 1999;116:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Tsevat J, Dawson NV, Wu AW, et al. Health values of hospitalized patients 80 years or older. HELP Investigators. Hospitalized Elderly Longitudinal Project. JAMA. 1998;279:371–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Puhan MA, Guyatt GH, Montori VM, et al. The standard gamble demonstrated lower reliability than the feeling thermometer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:458–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Souchek J, Stacks JR, Brody B, et al. A trial for comparing methods for eliciting treatment preferences from men with advanced prostate cancer: results from the initial visit. Med Care. Oct 2000;38:1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Bravata DM, Nelson LM, Garber AM, Goldstein MK. Invariance and inconsistency in utility ratings. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Investigating patients’ preferences for different treatment options. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:45–64. [PubMed]

- 33.Mehrez A, Gafni A. Quality-adjusted life years, utility theory, and healthy-years equivalents. Med Decis Making. 1989;9:142–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88:125–34. [DOI]

- 35.McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2001.

- 36.Dos Santos DM, Berridge DM. A continuation ratio random effects model for repeated ordinal responses. Stat Med. 2000;19:3377–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.SAS Software System. Version 9.1. In. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2000.

- 38.Pearlman RA, Starks HE, Cain KC, Cole WG, Patrick DL, Uhlmann RF. Integrating preferences for life-sustaining treatments and health state ratings into meaningful advance care discussions. In: van der Heide A, Onwuteaka–Philipsen B, Emanuel EJ, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, eds. Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects of End-of-Life Decision-Making. Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences; 2001.

- 39.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1507–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–91. [DOI]

- 41.National Institutes of Health. State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Improving End-of-Life Care. Bethesda, M.D.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

- 42.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1779–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Borum ML, Lynn J, Zhong Z. The effects of patient race on outcomes in seriously ill patients in SUPPORT: an overview of economic impact, medical intervention, and end-of-life decisions. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S194–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Shrank WH, Kutner JS, Richardson T, Mularski RA, Fischer S, Kagawa-Singer M. Focus group findings about the influence of culture on communication preferences in end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:703–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Ditto PH, Druley JA, Moore KA, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Fates worse than death: the role of valued life activities in health-state evaluations. Health Psychol. 1996;15:332–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Fried TR, van Doorn C, O’Leary JR, Tinetti ME, Drickamer MA. Older persons’ preferences for site of terminal care. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:109–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:30–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002.